Gem

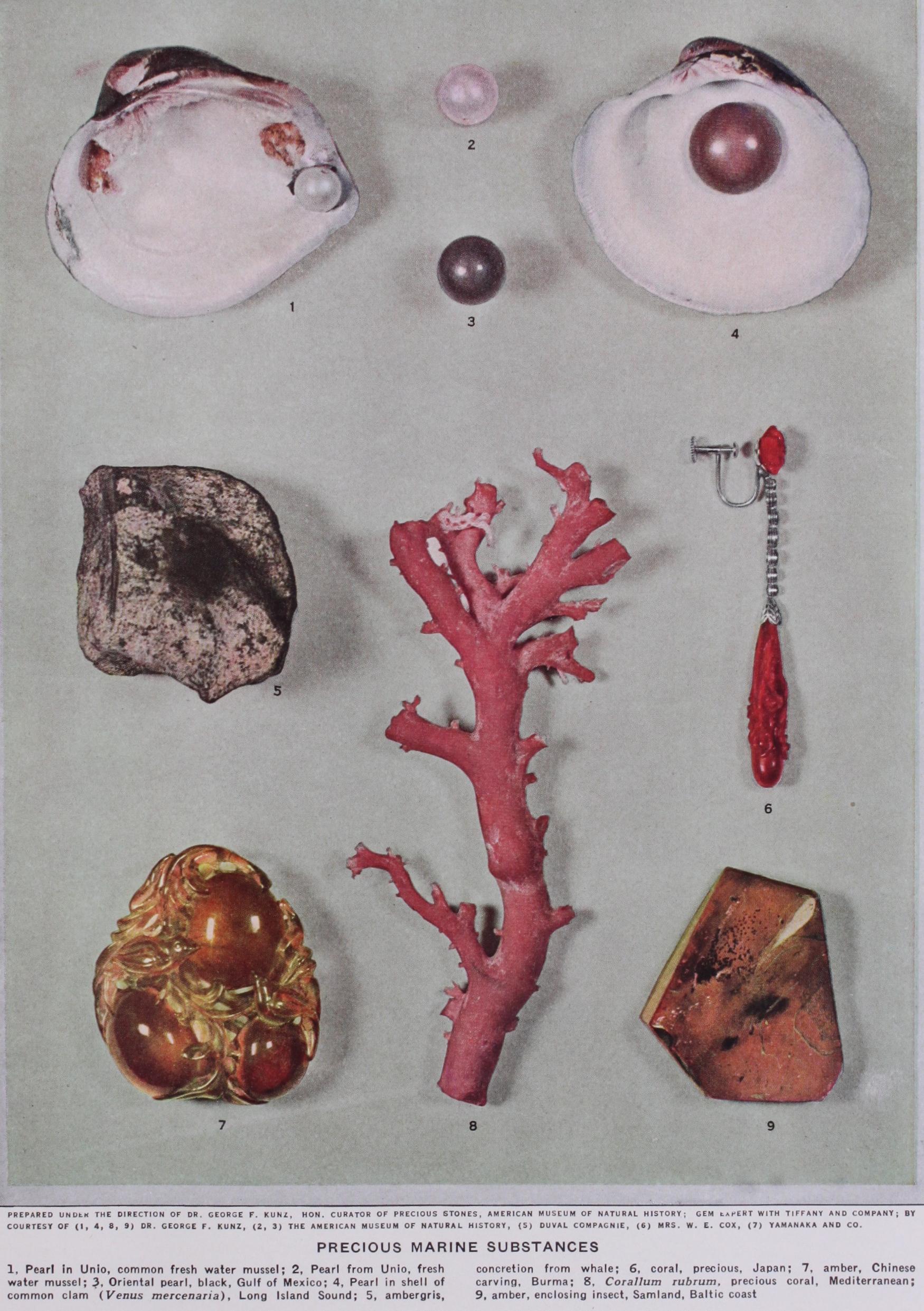

GEM, a word applied in a wide sense to certain minerals which, by reason of their brilliancy, hardness, and rarity, are val ued for personal decoration; it is extended to include pearl (Lat. gemma, a bud—from the root gen, meaning "to produce"--or precious stone). In a restricted sense the term is applied only to precious stones after they have been cut and polished as jewels, whilst in their raw state the minerals are conveniently called "gem-stones." Sometimes, again, the term "gem" is used in a yet narrower sense, being restricted to engraved stones, like seals and cameos.

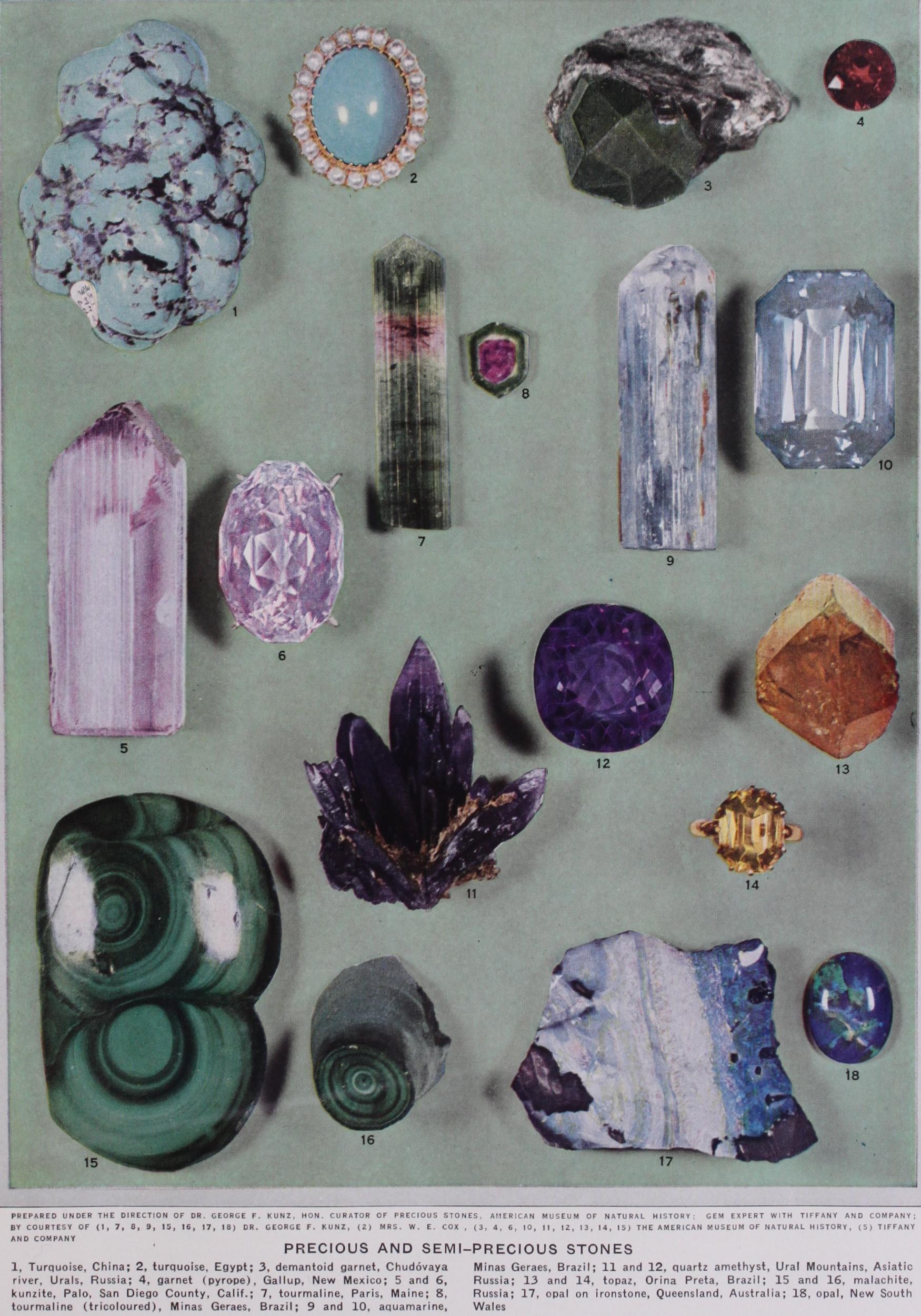

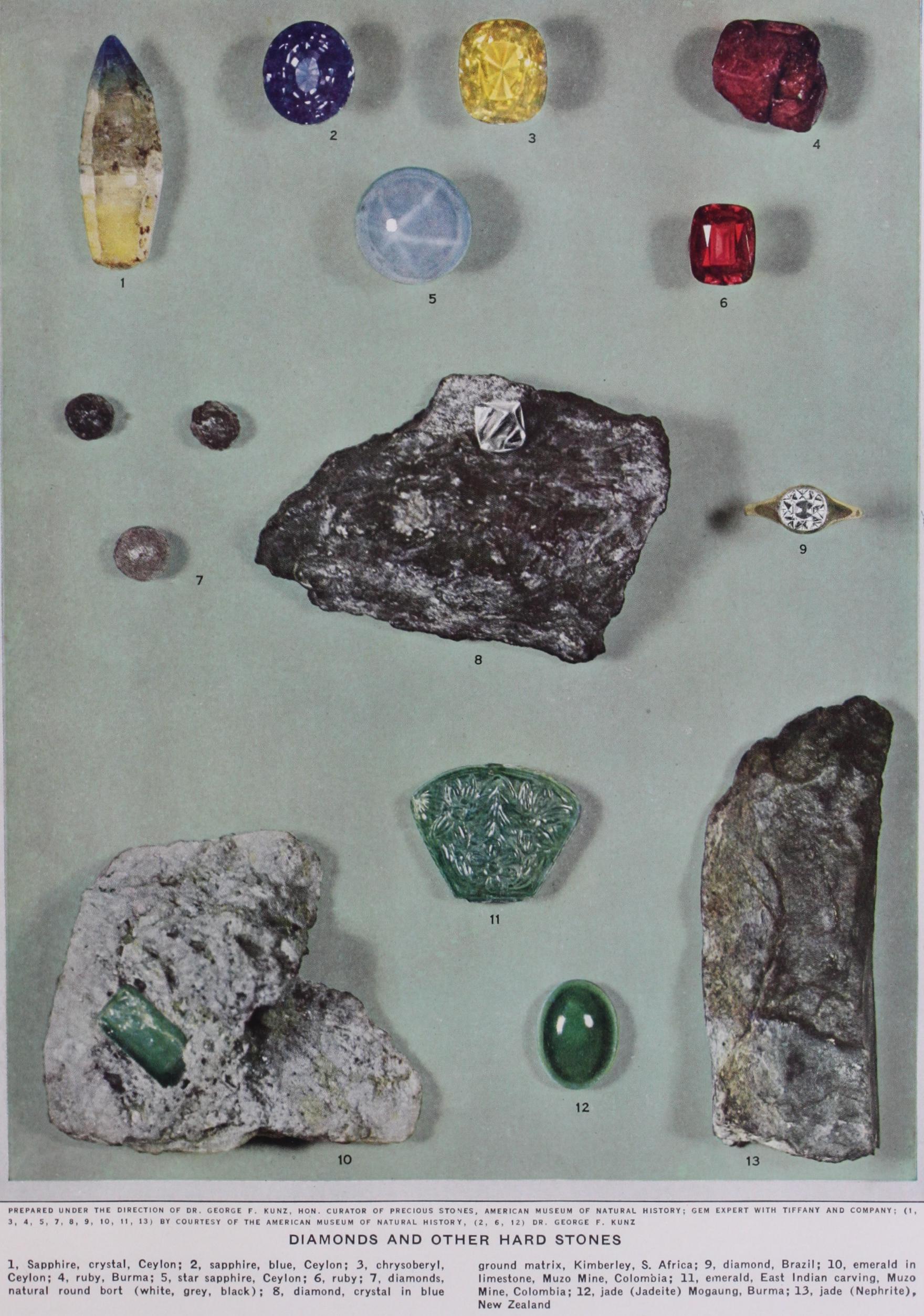

Confining attention here to the mineralogy and general prop erties of gems, it may be noted that the term "precious stone" is usually applied only to diamond, ruby, sapphire and emerald. Other stones, such as opal, topaz, spinel, aquamarine, chrysoberyl, peridot, zircon, tourmaline, amethyst and moonstone, are in cluded in the group "semi-precious stones," but the particular species in it may vary from time to time with changes in fashions. In the trade, owing to the vastly superior hardness of diamond, dealers in diamonds are sharply distinguished from those in other stones, a firm practically never handling both sorts, and in con sequence stones other than diamonds are grouped together and are known as "fancy stones." Descriptions of the several gem-stones will be found under their respective headings, and the present article gives only a brief review of the general characters of the group.

Crystalline Form and Cleavage.

Most precious stones oc cur crystallized, but the characteristic form is destroyed in cutting. The crystal forms of the several stones are noticed under their respective headings, and the subject is discussed fully under CRYSTALLOGRAPHY. A few substances used as ornamental stones, like opal, are amorphous or without crystalline form; whilst others, like the various stones of the chalcedony group, display no obvious crystal characters, but are seen under the microscope to possess a crystalline structure. Gem-stones are frequently found in gravels or other detrital deposits, where they occur as rolled crystals or fragments of crystals, having survived owing to their superior density and hardness.Many crystallized gem-stones possess the property of cleavage and tend to split parallel to planes intimately related to their atomic structure. This property must not be confused with the "parting" shown, for instance, by corundum which is the result of repeated twinning, the stones tending to split along the planes separating individuals. An easy cleavage, such as characterizes topaz, may render the fashioning of the stone difficult and pro duce incipient cracks in a cut stone; such flaws are called "feathers." The cutting of diamonds was very laborious until the discovery that the rough stone could easily be reduced by cleavage to an octahedron; owing to the use of high-speed cutting-discs in recent years, the practice of splitting diamonds has to some extent lessened. The method of cutting gem-stones is described under LAPIDARY.

Hardness.

A high degree of hardness is an essential property of a gemstone, for however beautiful a mineral may be, it is use less to the jeweller unless it be hard enough to take a brilliant polish and to withstand the abrasion to which articles of personal adornment are necessarily subjected. Paste imitations may be brilliant when new, but they soon become dull through rubbing or even chemical change of the surface. Minerals are arranged on the following arbitrary scale of hardness, which is due to Mobs : dia mond Io, corundum (ruby, sapphire) 9, topaz 8, quartz 7, felspar 6, apatite 5, fluor 4, calcite 3, gypsum 2, talc I. It is merely an order and has no arithmetical significance; thus diamond differs much more from corundum than does the latter from talc. Chrysoberyl scratches topaz but is scratched by corundum, and is therefore said to have a degree of hardness 84. A steel file will scratch any thing with hardness below 7. The test of hardness must be used with caution in order to avoid injuring the stone; it should pref erably be used to attempt to scratch a known mineral, for in stance a piece of quartz, and care must be taken to avoid break ing or splitting the stone.

Specific Gravity.

Gem-stones differ markedly among them selves in density or specific weight ; and, although this is a char acter which does not directly affect their value for ornamental purposes, it furnishes by its constancy an important means of dis tinguishing one stone from another. Moreover, it is a character very easily determined and can be applied to cut stones without injury. The relative weightiness of a stone is called its specific gravity, and is often abbreviated as S.G. The number given in the description of a mineral as S.G. shows how many times the stone is heavier than an equal bulk of the standard with which it is compared, the standard being distilled water at 4° C. If, for ex ample, the S.G. of diamond is said to be 3.5, it means that a dia mond weighs times as much as a mass of water of the same bulk. The various methods of determining specific gravity are described under DENSITY. The readiest method of testing precious stones, especially when cut, is to use dense liquids. The most con venient of them is methyline iodide, with density 3.32, which may be mixed with benzol, with density o.88. By pouring a little benzol on to methyline iodide in a tube and gently shaking it, a diffu sion column is formed and stones of differing density will float at corresponding depths. Chips of known stones may be used as indicators. Methyline iodide readily separates the true from the false topaz (yellow quartz) as the latter floats in it. For denser stones Retgers's salt, silver-thallium nitrate, may be used. It melts above 75° C. to a clear yellow liquid, miscible with water, with a density of 4.6.

Absorption : Colour, Dichroism, Etc.

The beauty and con sequent value of gems depend on the depth or the absence of colour. Diamonds are prized according to their freedom from any trace of colour, especially yellow, except that a slight bluish shade is greatly appreciated; colourless stones are said to be of pure "water." Corundum, topaz and quartz provide water-clear stones, but the absence of "fire" hinders their use. "Burnt" zircons have considerable fire and have been mistaken for dia monds. The value of coloured stones depends on their trans lucency and depth of tint. The colour of most gem-stones is not an essential property of the mineral, but is due to some pigmen tary matter often too minute in quantity for certain determina tion. Thus corundum when pure is colourless, and the presence of various mineral substances is responsible for the red of ruby, the blue of sapphire, and the many other shades of corundum that occur. The tinctorial matter is not always distributed uniformly throughout the stone, but may be arranged in separate layers or zones or even in irregular patches. Sapphire, for instance, is often patchy, only one small piece of the stone being blue and the re mainder yellow or white; the skilful lapidary arranges the blue patch on the culet so that, as all the emergent light traverses this portion, the effect is a uniformly blue stone. On the other hand, the remarkably variegated character of tourmaline is due to the complexity of its constitution which includes molecular groups exercising great tinctorial power. The character of the pigment in the case of a stone is often not definitely known. It by no means follows that the agent responsible for the colour of a piece of glass is capable of imparting the same tint to a natural stone : thus a glass of sapphire-blue may be obtained by the use of cobalt, but experience of synthetic stones has shown that cobalt will not diffuse without the addition of sufficient magnesia to produce a blue spinel and not a sapphire, and that a blue sapphire may be produced by the use of titanium. Probably ferric oxide causes a yellow, and ferrous oxide a bottle-green tint, and red is due to chromium, pink to lithium and manganese. Many colours fade on exposure of the stone to sunlight, pink being particularly fugitive.Exposure to heat often alters the colour and, when it brings about an improvement in the appearance of the stone, the method is often employed; for instance, the beautiful pink topazes are the result of heating certain yellow stones, and again certain brownish zircons can be decolorized by heat, the stones then on account of their brilliance and "fire" closely resembling diamonds. Radium emanations have the power of imparting colour to certain species, such as diamond, kunzite and quartz; the change appears to re sult from the displacement of electrons within the atom, and the original colour may be restored by exposure to light or the ultra violet rays, or by heating. The alteration in colour brought about by light or heat is due to the displacement of the constit uent atoms without derangement of their relative positions; the example of topaz shows that the displacement may be relatively considerable, because of the relatively considerable increase in the refractivity and density.

Inasmuch as the eye has not the power of analysis, the tint of a stone depends on the balance of the parts of the spectrum transmitted by it, and consequently the appearance of a stone in daylight and in artificial light may be different ; thus many sapphires darken in artificial light; in alexandrite the yellow part of the spectrum is absorbed, and in consequence the colour is green by daylight and cherry-red by artificial light. In certain zircons and in almandine-garnet, as was shown by Sir A. H. Church, the absorbed portions in the spectrum are narrow, and these stones show characteristic absorption spectra; in the former instance the cause of the peculiar absorption is a minute trace of uranium, so that all zircons do not show this absorption.

A doubly-refractive stone may exercise different absorption in the case of the two rays into which it splits up the light falling on it, and is then said to possess dichroism. Sometimes the dif ference is so marked, as in the instance of tourmaline and kunzite, as .to be discernible by the unaided eye, but generally a dichroi scope (see CRYSTALLOGRAPHY) must be used. In the direction of single refraction (optic axis) no dichroism exists, and therefore a stone must be viewed in several directions. Dichroism is a use ful property for distinguishing between ruby and garnet, as the latter, being singly refractive, shows no dichroism.

Lustre and Sheen.

The brilliancy of a cut stone depends upon the relative amount of light which is reflected from a surface and which itself depends on the refractivity and hardness of the stone. Diamond, being both very hard and highly refractive, has a lustre of its own, known as "adamantine"; zircon and deman toid approach it, but gem-stones generally have a "vitreous" lustre, like fractured glass.The presence of twin lamellae, fibres, or cleavage-cracks affects the appearance of the stone. The asterism of star-ruby or star sapphire is due to an arrangement of tubular cavities arranged at 6o° in planes perpendicular to the crystallographical axis. A sim ilar arrangement of fibres parallel to a single direction produces chatoyancy; cat's-eyes, as such stones are called, are provided by chrysoberyl and quartz, and tiger's-eye is a silicified crocidolite. Twin lamellae are responsible for the sheen of moonstone, and the peculiar iridescence of opal is caused by the interference of light within the stone.

Refraction.

As the optical properties of minerals are fully explained under CRYSTALLOGRAPHY little need be said here on this subject. In the "brilliant" form of cutting, the facets at the base of the stone are arranged so that the light refracted through a facet at the top returns in a nearly parallel direction but with lateral displacement so that it emerges through another facet. In the case of diamond with the highest refractive index of any gem stone (2.42) all the light is reflected at the base of a well-cut stone, and the same is very nearly true of zircon (the optically denser type, 1.93-1.98) and sphene (1.9o-1.98), but as the refrac tivity decreases a larger proportion of the light escapes at the base. Since most gem-stones contain in their constitution one or more of the molecular groups—silica, alumina, magnesia or their iso morphous equivalents—the refractivity and specific gravity are closely related as was shown by Sir H. A. Miers, but with the intro duction of other elements as in the case of diamond, sphene and topaz, the relation no longer holds. The refractive indices and the double refraction are important characters for the discrimination of gem-stones, and may be determined, except in the case of stones of very high refraction, by means of a total-reflectometer, for a faceted stone without its removal from the setting. A con venient form of refractometer, which may be used for indices ranging from 1.300-1.800, has been devised by Dr. G. F. Herbert Smith. Another instrument on the same principle but with longer focal length has recently been devised by Mr. B. J. Tully.

Dispersion.

Whenever light is incident on one facet and emerges through another not parallel to the first it is split up into a spectrum, the angular width of which depends upon the disper sion of the stone, this being measured by the difference between the refractive indices for the extreme red and violet rays. This play of colour is known as "fire," and is especially characteristic of diamond, which combines large dispersion with high refraction. Colourless zircon is not much inferior to diamond in "fire"; sphene and green garnet (demantoid) are even superior to it, but being coloured stones do not show it as conspicuously. .

Chemical Composition.

With the exception of diamond, which is crystallized carbon, the gem-stones are composed of alum ina or silica or a combination of them in varying proportions with or without other molecules. Corundum (ruby, sapphire) is alum ina, and quartz (rock-crystal, amethyst, etc.) is silica; spinel and chrysoberyl are aluminates, beryllonite, apatite and turquoise are phosphates, and the remainder are silicates of varying complexity of constitution. In the examination of cut stones chemical tests are obviously impracticable. The artificial production of certain gems, chiefly rubies and sapphires, by processes which yield prod ucts identical in composition and physical properties with natural stones is described in the article GEMS, ARTIFICIAL.Gem-stones have been imitated not only by paste and other glassy substances but by composite stones called doublets and triplets. In a doublet the front is real but the back paste, and in a triplet the front and back are real but the central section is paste, the purpose of which is to impart colour to the stone or to improve it. By immersing such imitations in oil or water, the bounding surfaces may be detected, and if the stone be unmounted it may be immersed in boiling water, or in alcohol or chloroform, when it will fall to pieces owing to the dissolution of the binding cement.

Nomenclature.

Before the days of mineralogy as a science the classification of gem-stones was vague and based almost solely on colour, which is the least reliable of all the physical characters, and the names which were used by early writers and mostly sur vive to this day, though not always with the same significance, are related to this character with possibly only one exception—dia mond (adiamentem, unconquerable, in reference to its supposed resistance to a blow with a hammer). Thus emerald (smaragdus) was used generally for green, sapphire for blue, ruby (ruber) for red, topaz for yellow stones. The earliest known lucid descrip tions of stones are contained in the great work on natural history by the elder Pliny, a victim of the great eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in A.D. 79. A study of them shows that many of the names though still surviving have a different significance ; thus his sapphire is known to us as lapis lazuli, and his topaz is our peridot.

Superstitions.

In early days gem-stones were believed to possess many magic virtues and charms; thus emeralds were sup posed to benefit the eyes and amethysts to prevent drunkenness. The belief in lucky stones still lingers, and the prejudice against opals as a source of misfortune has not wholly disappeared.BIBLIOGRAPHY.—The most comprehensive work on gem-stones is Bibliography.—The most comprehensive work on gem-stones is Prof. Max Bauer's Edelsteinkunde 0909), the first edition of which was translated, with additions, by L. J. Spencer under the title Precious Stones (1904) . A full account of the properties of gem-stones is given in G. F. Herbert Smith's Gem-Stones and their distinctive characters (4th ed. 1923). Summaries of the subject are contained in Sir A. H. Church's Precious Stones (1913), which serves also as a guide to the collections in the Victoria and Albert museum, and W. F. P. McLintock's Guide to the Collection of Gemstones in the Museum of Practical Geology, London (1912). Certain aspects of gem-stones have been discussed by G. F. Kunz in The curious lore of precious stones (1913) , The magic of jewels and charms (1915) , Shakespeare and precious stones (1916). Information regarding finds and localities is included in Mineral Resources, published annually by the United States Geological Survey. Other recent books which may be consulted are J. Wodiska, A book of Precious Stones (1909) ; A. Wruck, Die Geheimmisse der Edelsteine (1911) ; A. Eppler, Die Schmuck-und Edelstein (1912) ; C. Doelter, Die farben der Mineralien insbesondere der Edelsteine (1915) ; F. B. Wade, A text-book of precious stones for jewellers and gem-loving public (1918) ; A. E. Fersman, The coloured stones of Russia (1921), Precious and coloured stones of Russia (in Russian, 1922) ; Rosenthal, Au jardin des gemmes (1922) ; T. C. Wollaston, Opal: The gem of the Never-Never (1924) ; C. W. Cooper, The precious stones of the Bible (1924) ; H. Michel, Die kunstlichen Edelsteine (1926). (G. F. H. S.)