Gems in Art

GEMS IN ART. The word gem is used as a general term for precious and semi-precious stones especially when engraved with designs for sealing (intaglio) or for decoration (cameo). Such gems exist in large numbers from the early Sumerian period to the decline of the Roman civilization and again from the Renaissance to modern times. They satisfy the aesthetic sense in many ways. The inherent beauty of the material, with its rich and varied colours, its lustre and brilliance, gives pleasure at first sight. The hard and durable quality of the stones has made for unusually good preservation, so that we can appreciate in many cases the artist's work in its original state—a rare opportunity in ancient art. Moreover, the smallness and preciousness of the gems invited exquisite workmanship, and in certain periods, when art was at a high level, the achievements in this field were very notable. The best ancient gem engravers combined minuteness and accuracy of detail with a largeness of style that is indeed remarkable. A gem engraving of this class possesses the nobility and dignity of a marble or bronze sculptural work, though it is often confined to the space of less than half a square inch.

The Technique of Gem Engraving.

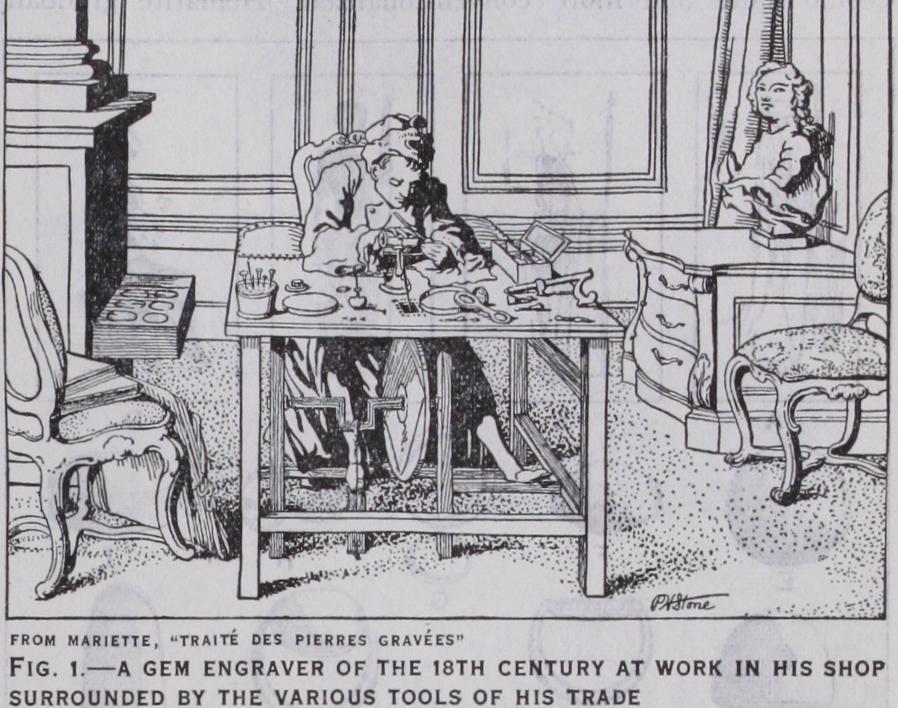

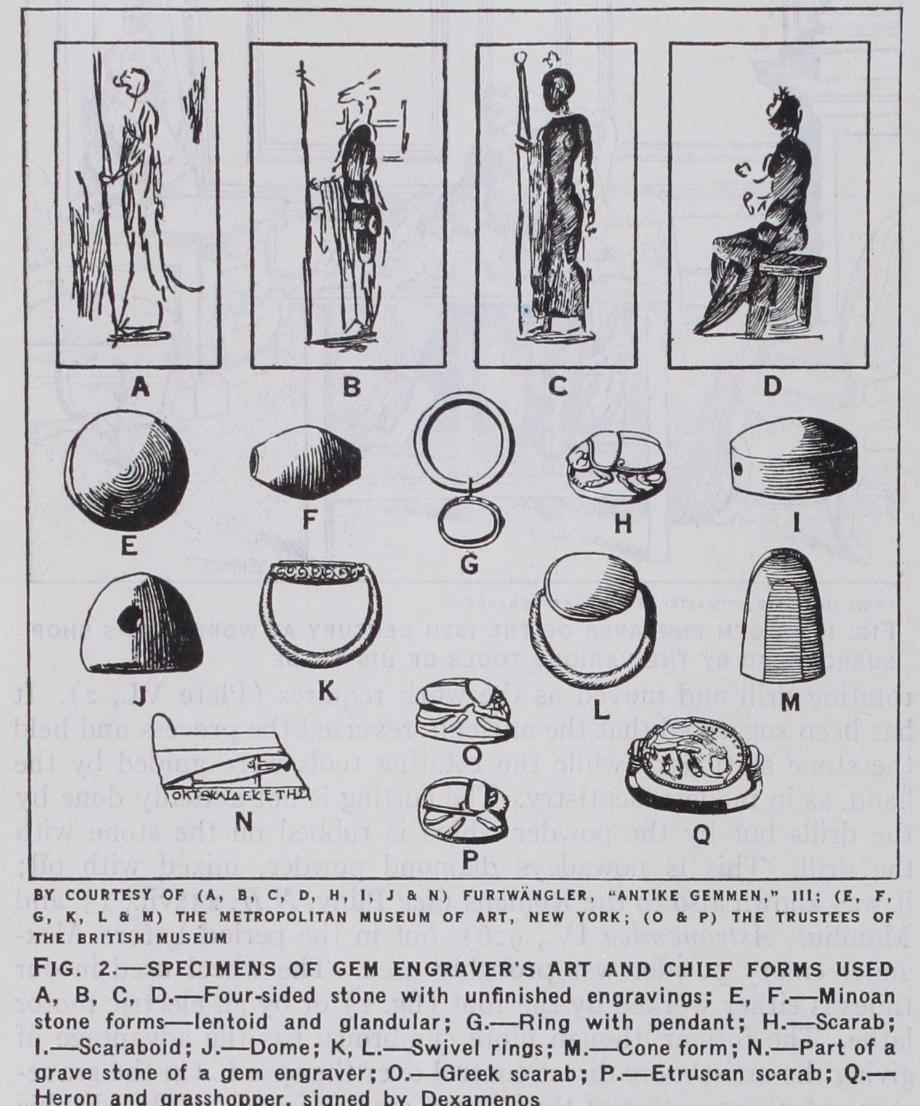

Only soft stones and metals can be worked free hand with cutting tools ; the harder stones require the wheel technique. This technique was known in Mesopotamia as early as c. 4000-300o B.C. (Plate II., I), as well as to the Minoans in the middle Minoan III. period (c. 1800-1600 B.C., Plate II., 13). The method of work seems to have been similar to that in use to-day, to judge by the references we have in classical literature (see especially Pliny, N.H. xxxvii., 76; xxxvii., 15 ; Theophrastus, De lapidibus I., 5; VII., 41), and an examination of the stones themselves (fig. 2 A, B, C, D). By this method the stones were worked with variously shaped drills ending in balls, discs, cylinders, etc. (Plate VI., which are made to rotate by the help of the wheel (fig. 1). Nowadays the stone to be engraved is fastened to a handle and held to the head of the rotating drill and moved as the work requires (Plate VI., 2) . It has been suggested that the ancients reversed the process and held the stone stationary while the rotating tools were guided by the hand, as in modern dentistry. The cutting is not actually done by the drills but by the powder which is rubbed on the stone with the drill. This is nowadays diamond powder, mixed with oil; it was known also to the Romans (see Pliny, N.H. xxxvii., 15, and Manilius, Astronomica IV., 926), but in the period before Alex ander emery powder was probably used. The wheel used in our times is either worked by the foot (fig. I) or by an electric motor lathe. The former, though more cumbrous, has the advantage of giving the artist more direct control over the speed. On the grave stone of a gem cutter of the Roman empire found at Philadelphia in Asia Minor (fig. 2, N) a tool is represented which looks like the bow used by modern jewellers and which, by being drawn back and forth, could impart a rotating movement similar to that of the wheel. But since we know that the rotating wheel was well known to the ancients in the making of pottery it is probable that they made use of it in gem engraving also. After the cutting of the gem was complete the surface was often polished. Such a polish was popular, especially among the Etruscans and in the later Greek and Roman periods. For this purpose Naxian stone (naxium) was used, as Pliny informs us (N.H. xxxvi., io).

We do not know definitely whether the ancient gem cutters made use of the magnifying glass but it is probable that they did. The general principle of concentrating rays was known to Aris tophanes (Clouds, 766 seq.). Pliny several times mentions the use of balls of glass or crystal brought in contact with the rays of the sun to generate heat (N.H. xxxvi., 67 and xxxvii., Io), and Seneca speaks more specifically of this principle applied for magnifying objects (Nat. Quaest. I., vi., 5).

Moreover, two crystal lenses dating from about 1600-I 200 B.C. have been found in Crete, and pieces of round glass in Egypt which may be early magnifying glasses.

Beck, Ant. J. VIII., 3, pp. (July 1928).

Mesopotamia.

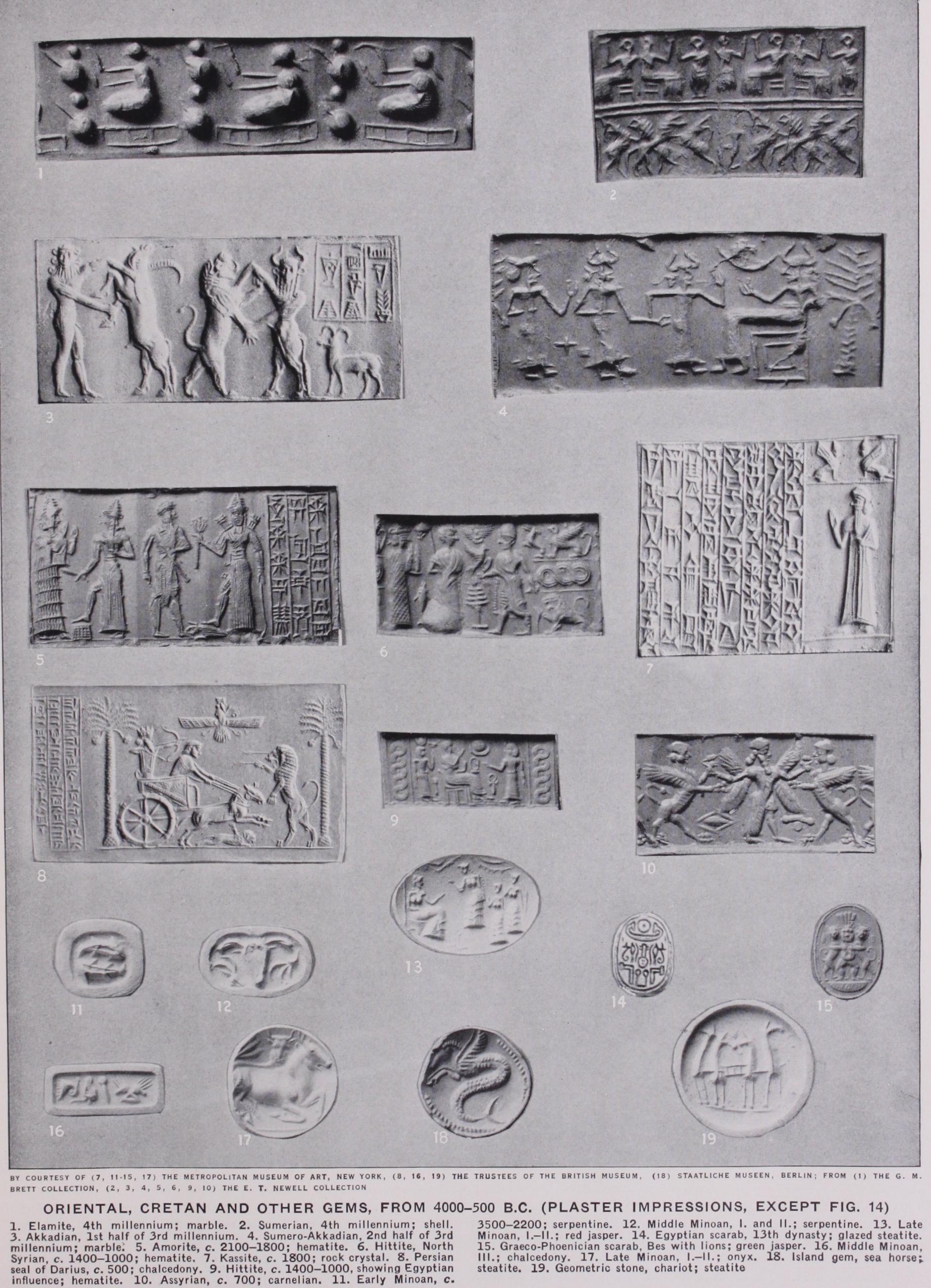

The art of engraving stones probably originated in south Mesopotamia. There it attained a high degree of pro ficiency as early as the fourth millennium B.C. ; i.e., during the Elamite and Sumerian civilizations. The engravings were worked on stones mostly of cylindrical shape (Plate I., 19), suspended by a string and used as seals. The materials were petrified shell and marble, and the subjects are chiefly heroes fighting animals, deities with worshippers and decorative motives (Plate II., 1, 2). After the Akkadian invasion (c. 2800 B.c.) the art of seal en graving reaches its greatest height, and semi-precious stones like rock crystal were cut in masterly fashion. The mythical King Gilgamesh performing his great exploits is the favourite repre sentation (Plate II., 3) . Cuneiform inscriptions begin to appear. After the decline of the Akkadian empire the representations become more and more conventionalized. Hematite gradually becomes the prevailing material. The most frequent subjects are the "Introduction Scene"—a seated goddess towards whom a second deity leads a worshipper, the Gilgamesh legend, and other mythical representations (Plate II., 4). During the Amorite dynasty (c. 210o-1800) , to which belonged the famous King Hamurabi, we are again in a highly artistic period, but probably of short duration. The representations are mostly the same as during the preceding epoch, and the use of cuneiform inscriptions becomes important (Plate II., 5), until in the Kassite period (c. 1800) it constitutes the most conspicuous feature (Plate II., 7).

After the downfall of the Amorites in Babylonia, southern Mesopotamia no longer played an important part politically, serv ing only as a cultural centre. The other oriental countries which now came into prominence naturally profited by the older civi lization, and the Hittites (second millennium B.c.), the Assyrians (first half of first millennium B.c.) and other peoples of Asia Minor all became conversant with the art of gem engraving. They carried on the southern Mesopotamian tradition with some contributions of their own (Plate II., 6, 9, 10). The favourite subjects are adoration scenes and heraldic groupings of deities and animals. Decorative motives are popular. The cylinder form remains in vogue, but conical and dome-shaped seals with a flat base for the intaglio are the most popular (fig. 2, 1, M). The coloured quartzes are the favourite material. When the power of Assyria gave way to that of Persia, the Persian gem engravers followed in the footsteps of their predecessors both in technique and style; but the favourite theme now becomes the exploits of the great king of Persia (Plate II., 8).

Egyptians early adopted the art of engraving, employing first the cylinder form, then, from about the 9th dynasty on, the scarab or beetle and kindred shapes. As subjects for their engravings they used chiefly symbols, script and orna ments (Plate II., 14), only occasionally pictorial scenes. Though historically, therefore, these scarabs are of great importance— especially as they have been found in great numbers and form a continuous series—the artistic value is 'frequently secondary. The great majority lack the interest of subject treatment, though the finish of their execution is remarkable. The commonest material is faience, but the coloured quartzes—carnelian, amethyst, jasper, etc., are also employed.

Crete.

From the earliest times we find Greece treading an independent path influenced but not conditioned by her oriental neighbours. In Crete gem engraving occupied an important place. The stones of the early Minoan period (c. 3500-2200 B.c.) show a great variety of shapes—including cylindrical, pyramidal, conoid, quadrilateral and three-sided rounded beads—and are engraved with rude pictographs, consisting of primitive renderings of human beings, animals, ships and floral and linear patterns (Plate II., i 1). It is clearly an experimental stage without traditional forms. The stone is invariably of a soft variety, i.e., steatite of different colours worked by hand. As time went on—during the first and second middle Minoan periods (c. 2000-1800 B.c.)—the three sided elongated bead became the standardized shape and the picto graphs were transformed into less rude, more conventionalized forms (Plate II., 12) . Several symbols now generally occur to gether, showing that from mere ideographic meaning they had acquired a phonographic value as syllables or letters. In other words, the primitive pictographs have evolved into hieroglyphs. The material still remains the soft steatite. During the middle Minoan third period (c. 1800-160o B.c.) the hieroglyphic script reached its full development, the symbols appearing in highly systematized form, executed often with great nicety (Plate II., 16) . The stones are now no longer steatite but hard varieties, such as carnelian, chalcedony and green jasper. They are worked with the wheel, this technique having been learned from the Orient.In the next period (late Minoan, c. 1600–i ioo) we note a great change. The Minoan written language has finally evolved into a linear script and concurrently it disappears from the seal stones. In its stead we find naturalistic designs—animals (Plate II., 17), cult and sacrificial subjects (Plate II., 13), deities and demons, hunting and war scenes, i.e., the stock subjects of Cretan art, executed with an amazing elan and vivacity. The stones are now regularly the hard quartzes, of lentoid and glandular forms (fig. 2, E, F). Similar engraved gems as well as gold rings with en graved bezels have been found at Mycenae and other places within the range of Cretan influence. Towards the end of the late Minoan period the art deteriorated. The soft steatite again took the place of the harder stones, and the subjects became merely conventionalized representations. Gradually there was established the geometric style in which linear designs were engraved by hand on soft stones of the prevalent oriental forms (Plate II., 18). In the 7th century B.C. a revival in artistic conceptions is noticeable. The use of hard stones worked by the wheel was reintroduced and the designs were largely borrowed from Eastern motives (Plate II., 18). And this was the prelude to several centuries of a flourishing output, lasting throughout the classical civilizations.

Greece.

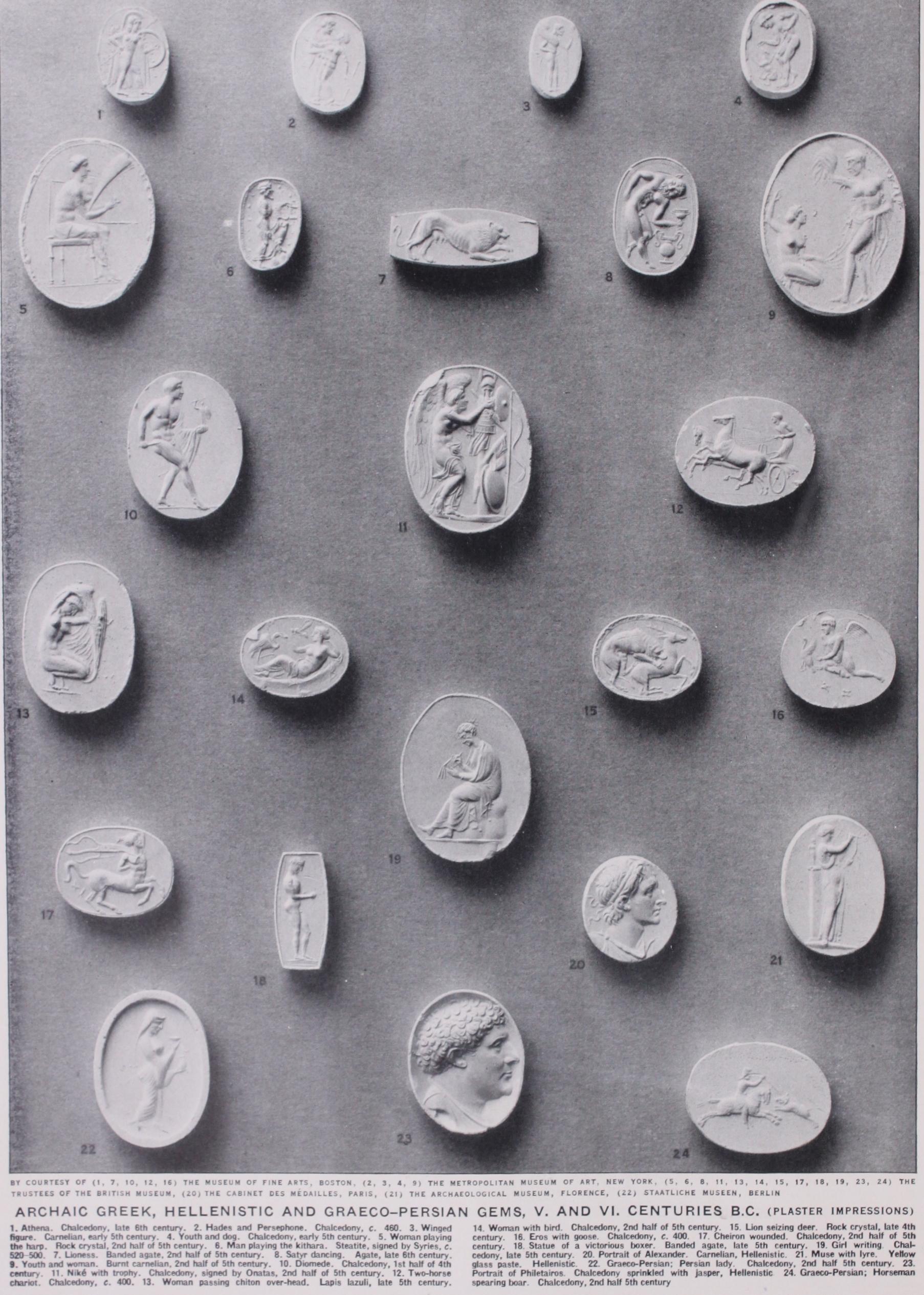

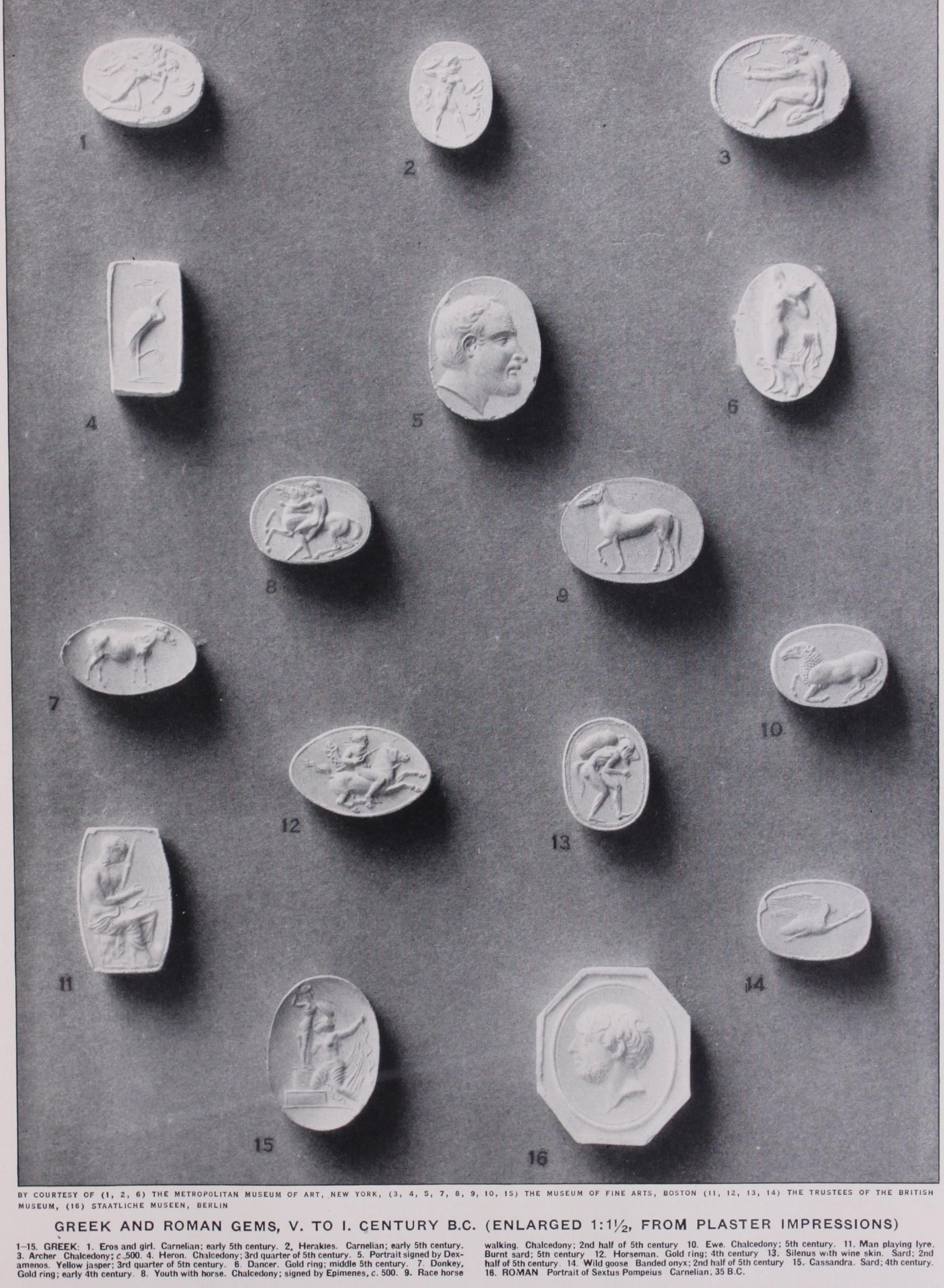

The study of Greek and Roman gems is the study of classical art in miniature ; for the gems reflect faithfully the styles of the various periods to which they belong, so that they represent an accurate picture of the development, the prime and the de cadence of classical art. In the gems of the 6th and early 5th century B.C. the dainty charm of archaic Greek art finds a happy expression. The chief forms are the scarab and the scaraboid (fig. 2, H, I) regularly set in swivel rings (fig. 2, K, L, Q). The sub jects are the same as in other branches of archaic art. At the beginning of the period the human figure in kneeling posture is the most popular, but soon a greater variety was attempted. Gods and goddesses are comparatively rare, but Herakles is a favourite; and various demons, the Silenus, the Siren and the Sphinx are also common. Among the figures without mythological signifi cance, the commonest are warriors, archers, athletes and horse men; and among the animals the lion, bull, boar, deer, ram, cock and horse (Plate III., 1-4, 6, 8 and IV., 5-3). The coloured quartzes, such as the carnelian, chalcedony and agate, are the chief materials used.

The second half of the 5th and the early 4th centuries mark another climax in the history of Greek gem engraving. We find the same conception of serene beauty in the minute products of the gem-cutters as in the contemporary statues. The favourite shape employed is no longer the scarab but the scaraboid (fig. 2, I), generally large and thick, and perforated to be worn on a swivel (fig. 2, L) or as a pendant (fig. 2, G). With regard to the choice of subjects the chief theme is now the daily life of the people, especially of the women. A woman taking a bath, making music, playing with animals, etc., are all favourite representations; animals are likewise common ; mythological subjects are less popular. The favourite deities are Aphrodite, Eros and Nike (Plate III., 5, 9, 10-19). By far the commonest stone of this period is the chalcedony. Less frequent are the carnelian, agate, rock crystal, jasper and lapis lazuli.

The inscriptions which occur on Greek gems form an interest ing study. They generally give the name of the owner, often only the beginning of his name being recorded. Occasionally they refer to the people represented or they contain a greeting. Sometimes the name of the artist is given. Of the latter the most prominent are Epimenes (Plate IV., 8) and Dexamenos (fig. 2, Q and Plate IV., 5) . Their works rank among the best which have been pro duced in Greek gem-cutting.

The Greek gems of the Hellenistic period about 323-30 B.C. reflect the somewhat heterogeneous styles of contemporary sculp ture ; but there are not many notable representations. A great change takes place in the shape of the stones. Instead of the per f orated scarabs and scaraboids the unperforated ringstone, gen erally flat on one side and convex on the other, becomes the accepted form. The stones are often of considerable size and the large rings in which they are mounted are not uncommonly pre served. The favourite stones are the hyacinth, garnet, beryl, topaz, amethyst, rock crystal, carnelian, sard, agate and sardonyx, many of them introduced into the Greek world from the East after the conquests of Alexander the Great. Glass, as a substitute for more precious material, is often used. Among the subjects represented the most important is the portrait, which now acquires great popularity (Plate III., 20, 23) . Scenes from daily life and mythology both occur (Plate III., 21).

A great technical innovation introduced in this period is the cameo, in which the representation instead of being engraved in the surface of the gem is carved in relief (Plate V., i 5) . It is therefore the converse of the intaglio. These cameos naturally did not serve as seals, as did the intaglio, but were used purely for instruments and jewellery. For such work the coloured quartzes were generally employed, their various layers being skilfully and effectively utilized ; but imitations in glass paste also occur (Plate I., 30).

Graeco-Phoenician and Graeco-Persian Gems.—Another class of gems in which the influence of archaic Greek art is strongly shown is that of the Graeco-Phoenician scarabs, chiefly found in the Carthaginian cemeteries of Sardinia (Plate II., 15). The stones there discovered show that during the 6th century B.C. Phoenician art was strongly subjected to Egyptian influence, but from the end of that century both the Greek style and Greek subjects were adopted. This archaic Greek style persevered in the Phoenician stones throughout the 5th century and into the 4th, long after a freer style had been introduced in Greece itself —a phenomenon with which we are familiar from Carthaginian coins. The shape of stone is regularly the scarab and the favourite material green jasper. The representations consist chiefly of the favourite Greek types of youths and men, and of mythological creatures. Fantastic combinations of heads and masks probably had an apotropaic significance.

The Graeco-Persian gems illustrate the influence of Greek art in the East. In Persia the gems of purely Persian style (Plate I., 8) are followed in the second half of the 5th and the first half of the 4th century by gems in which Persian and Greek elements commingled. They were evidently made by Greeks for Persians. The subjects are taken from the daily life of the Persian nobles, preferably contests of Persians and Greeks, or hunting scenes (Plate III., 24) , or single figures of Persian nobles or ladies (Plate III., 22). Animals are also favourite subjects. These representa tions are executed in a broad, spirited style, chiefly on chalcedony stones of scaraboid form. A rectangular shape with one faceted side is also popular.

Etruria.

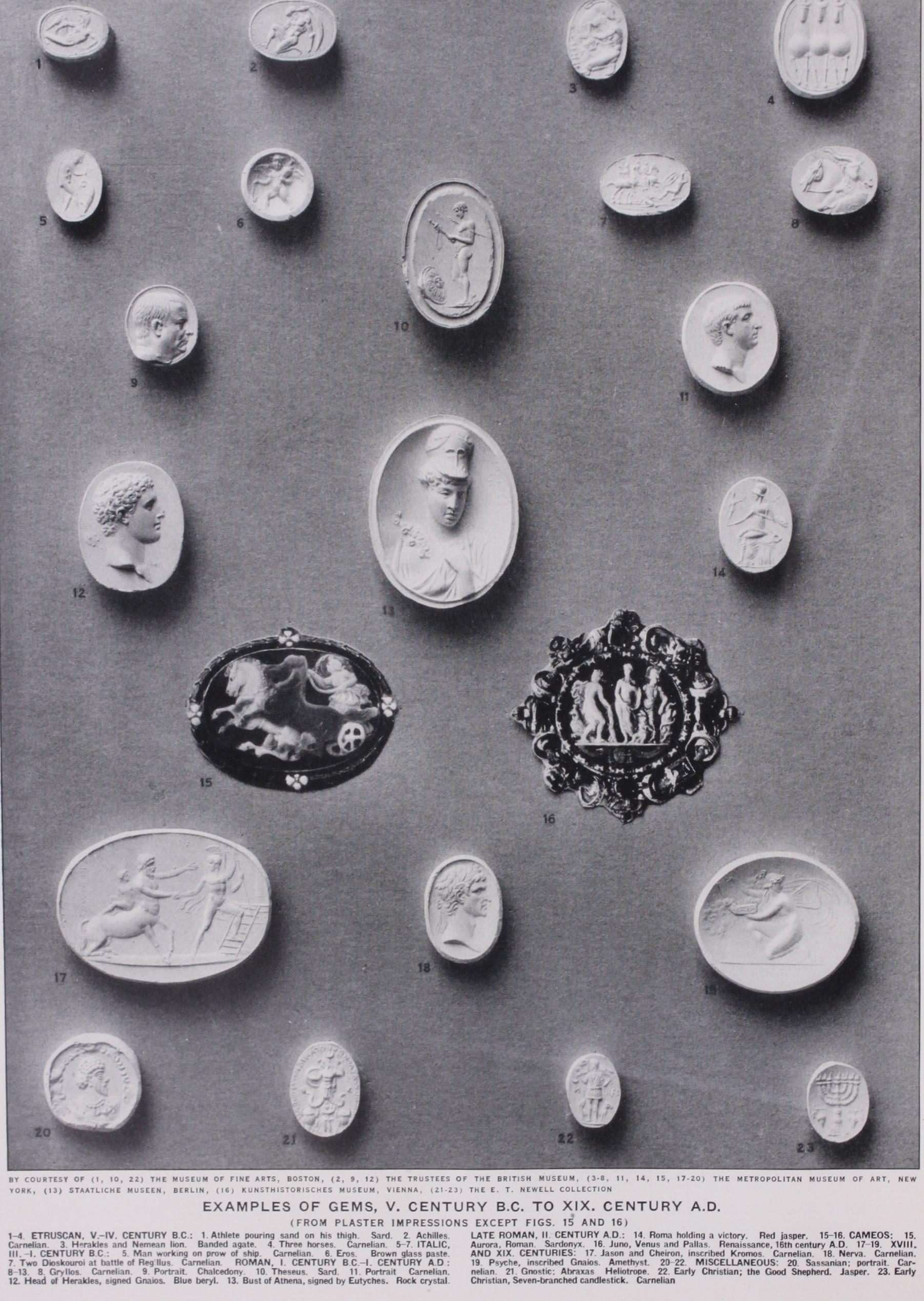

Etruscan gems make their appearance toward the end of the 6th century B.C. and remain in vogue until the 4th. They closely copy Greek styles, forms and subjects (Plate V., 1-4). At times their execution is excellent, but there is always a certain dryness and stiffness which serve to distinguish even their best products from pure Greek work. The shape is invariably that of the scarab, worked often with minute care, while to the Greek artist it was of secondary interest (compare fig. 2, 0 and P). Moreover, the edge of the base on which the beetle stands, which in the Greek examples is left plain, is ornamented in the Etruscan gems, except in the earliest period and in the more careless speci mens. By far the commonest material is the carnelian. The subjects chosen are chiefly taken from Greek mythology. Homeric and Theban heroes predominate (Peleus, Achilles, Odysseus, Ajax, Tydeus and Kapaneus). Inscriptions sometimes occur; but they do not, as in the Greek gems, give the name of the owner or of the artist but of the figure represented.At the end of the 5th century another class of scarab becomes prevalent, lasting until the beginning of the 3rd century B.C. It is not confined to Etruria but occurs also elsewhere in Italy. The distinguishing characteristic is that it is roughly worked with the round drill (Plate V., 4), evidently merely for decorative effect, which is heightened by the brilliant polish. Herakles and Silenus are the popular subjects.

Roman Gems.

The Etruscan scarabs are superseded in Italy in the 3rd and 2nd centuries B.C. by ringstones in which we can distinguish two styles, according as they imitate Etruscan (Plate V., 5) or Hellenistic art (Plate V., 6). There are no great artistic achievements among them but they are nevertheless of interest in that they form an important source of knowledge for the Roman art of the earlier republican period. In the ist century B.C. the two styles became merged, with Greek elements predominating (Plate V., 7) and growing gradually into the classicist style of the Augustan age.Engraved gems enjoyed a great popularity in Rome during the late republican and early imperial periods. We know this not only from the large number of examples which have survived but also from literary sources. Gem-collecting became a passionate pur suit. Wealthy men vied with one another in procuring fine speci mens and paid enormous prices for them. The keenness of this rivalry can be gauged by the story that the senator Nonius was exiled from Rome because he refused to give a certain gem (val ued at 20,000 sesterces) to Mark Antony. Public-spirited men, then as nowadays, after having formed their collections would de posit them in the temples for all to enjoy. Scaurus, the son-in-law of Sulla, is said to have been the first Roman to have a collection of gems. Julius Caesar was an eager and discriminating collector and deposited as many as six separate collections in the temple of Venus Genetrix. The style of the representations is that of the classicist art of the early imperial period which we encounter in other contemporary products. Its dominant characteristic is a quiet, cold elegance. The subjects have a wide range comprising mythological and every-day themes, including portraits of dis tinguished men, copies and adaptations of famous statues, symbols and grylloi—fantastic combinations of heads and figures, prob ably with superstitious import (Plate V., 8-13). The prevalent form is throughout the ringstone. The variety of stones used is large, for at this time of Roman world dominion and increased commercial facilities they could be obtained without difficulty from all parts of the empire. The commonest are the carnelian, sard, sardonyx, chalcedony and amethyst ; especially fine engravings are often found on garnets, hyacinths, beryls, topazes and peridots, more rarely on emeralds and sapphires. The nicolo and red jasper, which occurred only occasionally in former periods, now enjoyed great popularity. The Roman enthusiasm for this wealth of beau tiful stones can be gauged from the remarks of Pliny (N.H.

xxxvii., I) who declared that some gems are considered "beyond any price and even beyond human estimation, so that to many men one gem suffices for the contemplation of all nature." Cameos continued in use throughout this period, chiefly of sardonyx, onyx and glass paste (Plate V., 15). The favourite sub jects are portraits and mythological scenes. Among the former are valuable representations of emperors and princes.

Signatures of artists are found not infrequently both on the intaglios and cameos. In fact, by far the majority of ancient gem-cutters known to us belong to early imperial times. The most distinguished artist was Dioskourides, of whom we know that he made the imperial seal-ring of Augustus (Pliny N.H. xxxvii., 5o and 73) . Other well-known names are Gnaios (Plate V., 12), Aspasios, Eutyches (Plate V., 13), Aulos, Apollonios, Agathangelos (Plate IV., 16). (See GREEK ART; ROMAN ART.) Late Roman Period.—By the end century A.D. glyptic art was on the decline. Of the large number of gems of that period which have survived very few have any artistic value. The majority show hasty, careless workmanship and the representations are lifeless and monotonous (Plate V., 14). The shape of the gems is always the ringstone and the materials are very much the same as those in use during the preceding period. Nicolo and jasper now become specially common, probably on account of supposed magical properties.

The same deterioration is noticeable in the early Christian (Plate V., 22) and Gnostic gems (Plate V., 21) . A gem now be came a talisman with long, often unintelligible formulae. The symbolism is largely associated with Mithraic worship. The name Abraxas (or Abrasax) occurs with great frequency (Plate V., 21). The commonest materials are hematite and jasper.

More important artistically are the Sassanian gems (3rd to 7th century A.D.) which indeed represent the last important product of gem engraving in the ancient world. The representations are a mixture of oriental traditions and late Roman forms. Espe cially fine are some of the portraits (Plate V., 2o).

In north India the Ephthalites (white Huns) established a civilization about A.D. 475 which lasted until about A.D. 55o. That they too practised the art of gem engraving is shown by a recently discovered stone with the portrait of an Indian king (Plate I., 26).

Post-classical Times.

In post-classical times there are two epochs in which the art of gem engraving again flourished, the Renaissance and the 18th and early 19th centuries. The artists of both periods borrowed freely from the antique. Those of the Renaissance were too individual to keep very closely to the ancient spirit, and Renaissance works are therefore seldom difficult to dis tinguish from ancient gems (Plate V., 16) . The gem engravers of the i8th century, on the other hand, had little inspiration of their own, and consciously tried to copy ancient work as exactly as possible. And though at first this copying was done purely out of admiration for the antique, it soon developed with unscrupu lous people into an extensive output of forgeries. At times it is extremely difficult to tell definitely whether a certain piece is ancient or a faithful copy. Mostly, however, the copyist betrayed himself by a slight innovation characteristic of the spirit of his own time rather than that of the antique (Plate V., 18) ; and in a large number of cases, notably in the famous Poniatowski gems (Plate V., 17, 19), the spirit and composition are so far removed from ancient work that few people would nowadays be deceived by them.An interesting feature of the gems of this period is presented by the inscriptions which often appear and give the signatures of the artist or would-be artist. For besides signing their own names, often in Greek or Roman letters, it became the practice to sign the name of a famous ancient artist. Generally such forged inscriptions are easily detected, but sometimes they are cut with great care and present a difficult problem. More over, at times genuine ancient gems are supplied with forged signatures. The best-known gem-cutters of this period are the famous Natter, the three Pichlers, Marchant and Burch.

In modern times the art has a certain limited vogue, not corn parable, however, with the great periods we have described.

Menant, "Les pierres gravies de la haute Asie," Recherches sur la glyptique orientate (1883-86) , the best general account; O. Weber, Altorientalische Siegelbilder (Iq17), the best account of artistic development; D. G. Hogarth, Hittite Seals, with Particular Reference to the Ashmolean Collection (192o) ; G. Couteneau, La Glyptique Syro-Hittite; L. Dclaporte, Catalogue des cylindres, cachets et pierres gravies de style oriental du Muse du Louvre (192o-23) , chief emphasis on subjects represented ; L. Legrain, "The Culture of the Babylonians, from their Seals in the Collections of the Museum," University of Pennsylvania Museum, Publications of the Babylonian Section, xiv. (1925), important for chronology. Egypt.—F. Petrie, "Royal Tombs of the First Dynasty," Egypt Explor. Fund. XVlIIth Memoir, p. 24, Pl. xii., fig. 3-7, and P1. xviii.–xxix.; P. E. Newberry, Egyptian Antiquities, Scarabs, an Introduction to the Study of Egyptian Seals and Signet Rings (1906) ; H. R. Hall, Catalogue of Egyptian Scarabs, etc., in the British Museum, vol. i. (1913) . Crete and Mycenae.—H. von Fritze, "Die 'Mykenischen Goldringe and ihre Bedeutung fur das Sacralwesen," in Strena Helbigiana (1 goo) ; D. G. Hogarth, "The Zakro Sealings," in Journal of Hellenic Studies, xxii. (1902) ; A. J. Evans, Scripta Minoa (1909) and The Palace of Minos at Knossos, i. (1921) and ii. (1928) Classical Gems.—A. Furtwangler, in Jahrb. des deutschen arch. inst., vol. iii.–iv. (1888-89) , articles on "gem-engravers" and Antike Gemmen, i.–iii. (1900), the fullest and best general account of the subject; M. N. H. Story-Maskelyne, The Marlborough Gems (187o) ; S. Reinach, Pierres gravies des collections Marlborough et d'Orleans (1895) ; A. Furtwangler, Beschreibung der geschnittenen Steine im Antiquarium (1896) • E. Babelon, Catalogue des camees antiques et modernes de la Bibliotheque Nationale (1897) ; J D. Beazley, The Lewes House Collection of Ancient Gems (1920) ; G. M. A. Richter, Catalogue of Engraved Gems in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (192o) ; H. B. Walters, Catalogue of Engraved Gems and Cameos in the British Museum (1926) . For a list of 16th to i8th century publica tions of gem collections, see A. Furtwangler, Antike Gemmen, iii., pp. 402 ff. Sassanian Gems.—P. Horn, Sassanidische Siegelsteine von P. Horn and Georg Steindorff (1891) . Gnostic Gems.—Cabrol, Dict. d'Archeologie chretienne, s.v. "Abrasax." Post-Classical Gems.—O. M. Dalton, Catalogue of the Post-Classical Gems in the British Museum (1915) , with useful bibliography. (G. M. A. R.)