Isostasy

ISOSTASY.

Floating Continents.—According to the most recent ideas the continents form more or less permanent units, blocks consisting of rocks of low average density which behave as if they were floating in a substratum of some plastic and considerably heavier material. This heavy material, which is supposed to have the composition of basalt, is found at or very near the floors of the great ocean basins, and extends under both oceans and continents to a very great depth. Further, in order that the equilibrium of floating may be maintained any extra high elevation on the top of a continent, e.g., a mountain range or plateau, must be balanced or compensated by a corresponding bulge downwards of the lighter rock of the continental block. According to this theory the con tinents are regarded as behaving like ice-floes and icebergs float ing in the sea. If we know the densities of water and ice and the amount that the floe projects above the water, we can calculate the thickness of the part submerged. Similarly, in the case of a continental block; if we know its average density and that of the substratum, as well as the average height of the continent above the sea-floor the thickness of the continental block can be calcu lated, theoretically at any rate, for—since both are so uneven— the difficulty of determining the average height of the continent above the average sea-floor complicates matters.

Rise and Fall of Land Masses.—Now suppose such a floating continent is undergoing denudation ; it is necessarily becoming lighter and will therefore rise, and the same effect will be pro duced if a great ice-sheet melts. On the other hand a continent may be made heavier by the formation of an icecap, or by the outpouring of great floods of lava, as has indeed happened in earlier geological times ; while another cause that has been invoked to account for continental sinking depends on the melting of part of the substratum by heat generated by radioactive disintegration, the substratum thus losing part of its density and the equilibrium being deranged. This explanation is, however, at present regarded as highly speculative.

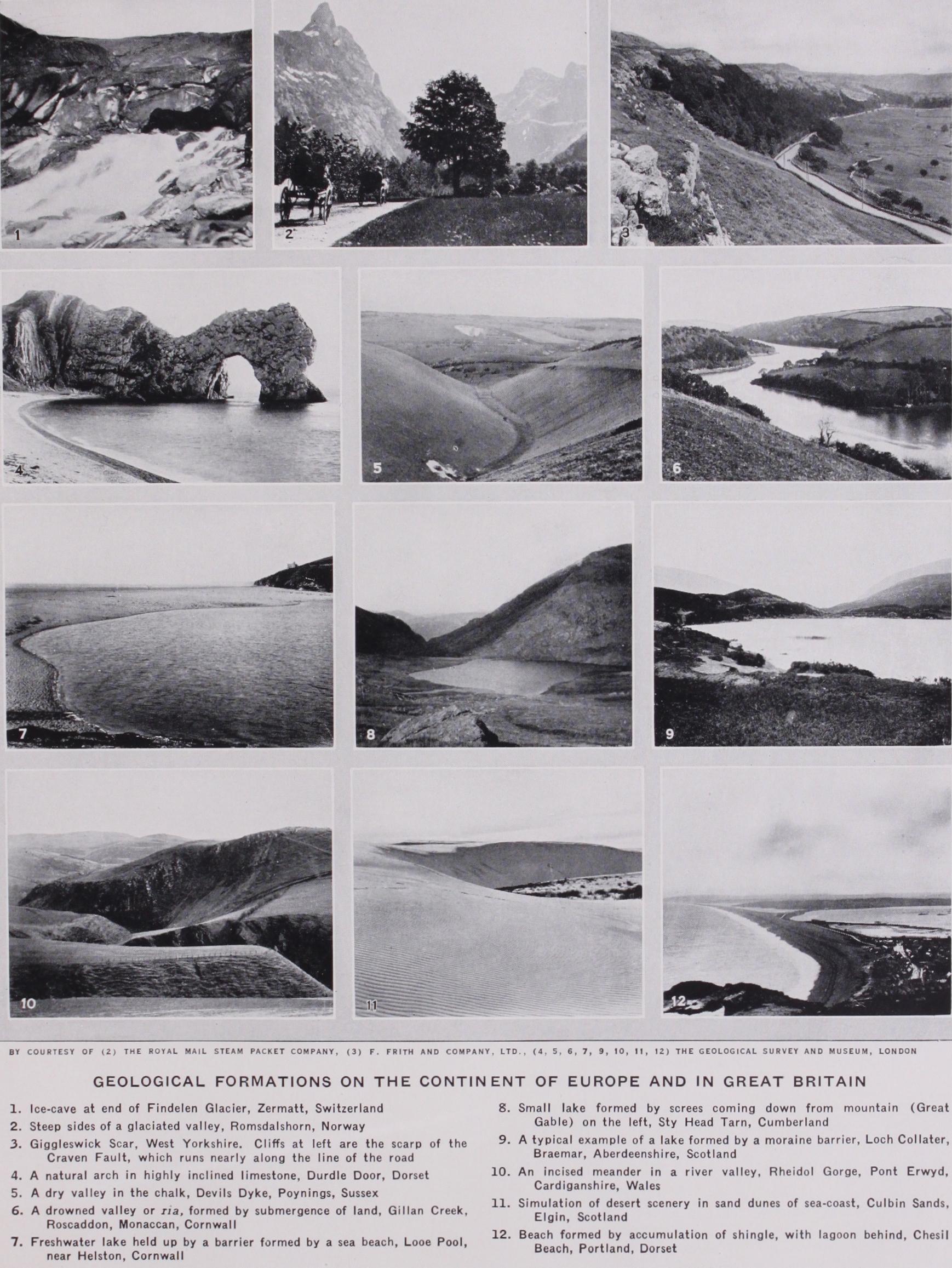

Many of the facts of geological observation, such as raised beaches, drowned valleys and what are called transgressions of the sea over the land on a large scale, as well as the correspond ing general emergences, certainly seem to indicate that extremely widespread and uniform movements do take place, of just the kind that would be expected in accordance with the theory or group of theories here outlined. It is also clear that the greater movements of this kind may also be accompanied by subsidiary effects on a smaller scale, such as fractures of the crust and similar phenomena. These must, however, of necessity be very similar to the types to be presently described as resulting from a special kind of tangential force and the two may conveniently be discussed together.

Movements with a Horizontal Component.

The full dis cussion of these phenomena involves some of the most difficult problems of modern geology. However, we can discriminate be tween the causes and the effects. For the first-named, reference may be made to the article, EARTH. The main geological im portance of the effects is the part played by them in the structure of the visible crust, the effect on topography and scenery, and— what is of vastly greater importance—the economic bearing of such structures in mining and allied industries. And it is well worth while to emphasize the fact that the highly complex struc ture of many mining areas, especially coalfields, has been eluci dated, and their economic working made possible, as a result of what were in their inception purely theoretical studies of earth structures in some of the more complicated regions.Tension and Compression.—Movements possessing a horizon tal component result sometimes in tension (stretching) of the earth's crust, sometimes in compression, and the effects in the two cases naturally show differences. It may be remarked in pass ing that tension in one place is usually accompanied by compres sion elsewhere, since the total volume of the crust, regarded as a skin, does not change. In the early days of the earth's history, the crust probably did shrink in volume, owing to contraction on cooling, but for long ages its temperature has obviously been pretty constant, whatever may have happened to the interior. Hence mere shrinking of the crust will not account for its move ments, nor, above all, for the forces of tension that have affected it.

In discussions of the general aspects of this subject, stress has been laid on the idea that after the crust cooled to a constant volume the interior may have gone on shrinking so that the crust became too large for it and tried to adjust itself to the new con ditions by wrinkling like the skin of a dried apple. A few years ago most geologists poured scorn on this simple conception, but it has lately been revived, especially in Germany, and it certainly deserves grave consideration.

As a result of these processes, whatever their origin, two fairly clearly defined types of structure are produced—faults (q.v.) and folds (q.v.). It must be understood, however, that there are types of structure intermediate between them, or combining the two, in that folds, when pushed too far, often pass over into faults, just as excessive crumpling of a sheet of metal may cause it to crack. Furthermore, an extreme degree of compression often results in cleavage (see SLATE and SCHIST).

It has already been mentioned that lateral movements of the earth's crust may occasion either tension or compression, and that the resulting structures in each case are characteristic. It is not difficult to see that the chief result of tension will be cracks, i.e., faults, while in compression folds will be dominant. Now the formations produced in regions of tension will in many ways resemble, though on a smaller scale, the results of the purely vertical movements already described. Naturally, one of the principal consequences of such movements will be the tilting and sinking of blocks between faults; it is difficult to see how they could ever result in elevation, for it seems inevitable that the only real movement possible under gravity is sinking; but in geology, movement always appears relative.

Plateau-building Movements.—Now if the crust, in a region of more or less horizontal strata, is cut up into blocks in this way, as a result of relative movement some may be left higher than others, forming plateaux. This result is so common and char acteristic that the whole group of phenomena are often summed up as plateau-building movements.

The subject has been studied systematically in the Great Basin region, the area lying between the Rocky Mountains on the east and the Coast Ranges on the west, where conditions are specially simple and favourable for generalization. The Rockies are the result of a thrust towards the east, while in the Coast Ranges, the thrust was towards the west ; hence the area between was stretched and cracked, and collapsed in blocks with tilting of the individual blocks. As is so often the case, the collapse was accompanied by great floods of basaltic lava, which helped to weigh down the blocks. In some cases the strata were not cut clean through by faults, but bent sharply at the edges of the blocks. It appears that similar structures can also be produced by the forcing in below the surface of a mass of molten material, as explained in the section on igneous intrusion. In this case the surface may have been uplifted in the absolute sense, but this phenomenon belongs to a rather different category.

Block Structure in Britain.—Some of the types of structures just described as characteristic of plateau-building movements are also to be seen in the British Isles, though there the conditions are not quite so simple. Some of the best-known examples are found on the western side of the Pennines, on the borders of Yorkshire, Durham and Westmorland. Here the rocks are on the whole uplifted to form a very flat arch, steeper on the west than on the east. Especially on the western side, cracks and flexures developed in this arch, and the general result is very like the block-structure of the Great Basin, on a smaller scale. The blocks are separated by great faults, some of which show a very large displacement. Similar structures are also developed among the younger and less-disturbed rocks of many parts of the world where the conditions, on the whole, have involved tension rather than compression.

Effects of Compression.—When we come to consider the types of structure produced as a result of compression, the matter is much more complicated. The general effect is in most cases a combination of folding and faulting, sometimes one being domi nant, sometimes the other, and it is with the general effects on topography and surface forms of certain types of these that we now have to deal.

One of the fundamental general principles is that violent move ments of compression tend to occur periodically throughout geological history and that their occurrence is usually confined to certain fairly well-defined regions of the earth, often taking the form of long narrow zones. Furthermore, when a given region has once been compressed and folded there is always a tendency for similar effects to occur along the same or nearly the same lines. Without entering into a discussion of causes, a brief out line may be given of the usual order of events in an area affected by movements of this kind.

Mountain-building.—The first phase is that a long narrow area of the earth's crust, usually part of the sea floor, begins to sag, forming what is known as a geosynclinal: at the same time depo sition of sediment goes on pari passu with the depression, so that eventually an enormous thickness of shallow-water marine sediment of very uniform character is accumulated, sometimes amounting to 50,000 feet. After a long time, probably owing to rise of temperature due to the blanketing effect of the sediment, the direction of movement is reversed and the geosynclinal begins to swell up and eventually as it were, boils over. At the same time the two stable margins of the trough approach each other, like the jaws of a vice, which accentuates the outward movement of the top layers. The rising strata are naturally thrown into violent folds, which tend to topple over outwards, and are often cracked and torn in the process. Broadly speaking, the effect is the production of mountain chains consisting of strata that have been strongly folded, fractured and over-thrust in one or more dominating directions.

It may happen that the thrust is mainly from one side, when the chain may consist of a series of nearly flat folds; on the other hand if the pressure from the two sides is nearly equal, the structure will be fan-shaped. The outer, complex margins of the fan may be separated by a considerable width of less complicated structure; sometimes, apparently when the main pressures have slacked off, this central portion may collapse and fall back to some extent. Such appears to be the origin of the Great Basin of western America, as before described, and it has been suggested that the Mediterranean region is actually a col lapsed area between two mountain chains, the Alpine and Atlas systems—a complicated and much disputed question in which, however, it is generally admitted that the Mediterranean basin is a sunken area whatever may be the relations of the mountain chains around it. The plain of Hungary is another, on a smaller scale.

It must be clearly understood that a mountain chain in process of formation in the way just outlined may at the same time undergo denudation, so that the strata need not necessarily form such an enormous pile above the earth's surface as would be indicated by a theoretical restoration of all the missing bits of the folds. And we have also to consider the fact, which may be regarded as established, that rocks are only plastic when under a heavy load; near the surface they tend to fracture rather than to fold, forming thrust-planes and faults. Some thrust-planes, which are really only very flat faults, have a displacement to be reckoned by tens of miles—e.g., the great Moine thrust in N.W. Scotland (see SCOTLAND, Geology) and the still greater Scan dinavian overthrust in Norway and Sweden.

In this discussion we have hitherto dealt with phenomena on the very largest scales, measurable by miles in extent and thou sands of feet in thickness. But in point of fact similar effects are found in every possible degree of magnitude. Precisely similar structures can be seen in slabs of rock only a few inches across, and even thin sections of rocks prepared for the microscope sometimes show them in the space of a few millimetres. Examples of complicated folding on a comparatively small scale, with its accompanying shattering and cleavage, are abundant in nearly all areas where the older rocks are exposed.

Vulcanicity.—This term will be used in a somewhat broad sense, to include not only the phenomena belonging to volcanic eruptions proper, but also those of an analogous character which occur in the depths of the earth's crust ; the underlying cause is the same, the difference in the effects depending only on con ditions.

The basis of the subject is the fact that the interior of the earth is very hot. At a depth of only a few miles the temperature is high enough to melt metals and all rocks such as we know at the surface. Whether the material is actually liquid is a moot point: at any rate it is potentially so. It is possible that it is really kept solid by the tremendous pressures that prevail in depth, but is liquefied if such pressure is in any way relieved, for example, by earth-movements. It is obvious that it is sometimes liquid, as shown by the streams of lava (q.v.) poured out by volcanoes. Geological observations also show that at times molten material has been injected underground into already existing rocks or into spaces between them. It is this aspect of the subject that will be chiefly described here. The superficial effects in general are dealt with under VOLCANO.

Magma.—The molten rock-material is, before its consolidation, usually spoken of as magma whatever its chemical composition; the types of rock that result from its consolidation are dealt with under PETROLOGY, and in numerous other articles under the appropriate headings. It is mainly the forms assumed by such masses that will here be considered, without much reference to their composition or nomenclature. These forms depend on several factors. In a superficial lava-flow one very obvious determinant is the form of the surface over which it has to run, and particularly the steepness of the slope; but another very important matter is its viscosity, which depends on two totally independent factors— its temperature and its chemical composition. Naturally, very hot lava flows more freely and, therefore, as a rule further than a cooler mass; and lavas which are rich in silica and alumina are much more viscous at any given temperature than those in which iron and magnesia are the characteristic constituents (see PETROLOGY). Consequently, dark-coloured lavas of the kind called basalt (q.v.) are the most liquid and tend to spread out into the thinnest sheets under any given conditions, whereas rhyolite and trachyte (qq.v.) often form thick lumpy masses close to the orifice of the volcano, or even fail to escape into the open at all.

Extrusive and Intrusive Rocks.—The mention of this fact leads to the other part of the subject, viz., the behaviour of intrusive magma, that is, magma that never reaches the surface, as even the most liquid lavas may fail to do. There is often an actual physical connection between a mass of rock poured out on the surface (extrusive magma) and the underground reservoir from whence it came ; this gives us the simple classification of solidified masses of magma—extrusive and intrusive.

We must now consider the factors controlling the forms and positions of intrusive masses, as thus defined. All the consider ations already detailed as to temperature and viscosity are equally applicable here, but instead of the forms of a surface we have to take into account the position of lines and planes of weakness in the rocks invaded by the magma, as well as the thickness and weight of the overlying crust. Another important thing is that when molten magma is confined underground, the steam and other vapours cannot readily escape from it, as they do at the surface, and their pressure helps to raise and fracture the rocks, and to drive a way for the passage of the magma; in fact the motive power behind it is very largely this vapour pressure, whether it escapes at the surface or is intruded below.

Planes of Weakness.—The planes of weakness in rocks may be classified as bedding-planes, joints, faults (see these headings), cleavage-planes and certain parts of folds. The forms assumed by intrusive masses are largely controlled by the different possible arrangements and combinations of any or all of these : the varie ties are therefore endless ; but it is not very difficult to select a few common types having some distinctive character about them.

First may be considered the kinds of intrusion possible in hori zontal, or nearly horizontal, strata with well-defined bedding. It is evident that in order to reach such strata, if fairly near the surface, the magma must come up some more or less vertical fissure. It appears that often, on reaching a certain level in such a fissure it is easier for the magma to spread out sideways along bedding-planes, lifting the roof, rather than to go on cutting a vertical fissure. The point at which this spreading begins is controlled by the rate of the weight of the overlying rock to the driving power of the magma.

Sills, Laccoliths and Bysmaliths.—Now, other things being equal, a very liquid magma will be able to spread further along a bedding plane than a viscous one. In the first case, the result will be a flat sheet of rock of any thickness, with its top and bottom nearly parallel for a long distance, of course eventually closing up at the ends. Such flat sheets, thin in comparison with their lateral extension, are called sills (q.v.). If on the other hand the magma is viscous, it will take a form something like a gi gantic bun—thick in proportion to its extension—called a laccolith (q.v.) . All such masses necessarily have a feeder in the form of a crack or pipe filled with magma, and must be more or less in the form of a mushroom, although the "stalk" is rarely seen and often ignored. Geometrically the feeder may be either a point or a line, and the resulting form of the whole will naturally vary somewhat in accordance. Certain related forms called bysmaliths or plutonic plugs, have been described by American authors.

Dykes.—Cracks similar to these magma-filled feeders often fail to spread out into mushrooms, or to allow their contents to overflow as lava-sheets at the surface; and, in other cases, the mushrooms or sheets have been removed by denudation leaving only the feeders. These more or less vertical sheets of rock formed by consolidation of magma and traversing all other rocks, form a well-defined geological unit, to which the term dyke (q.v.) is applied. The name is the Scotch word for a stone wall which, on denudation, they resemble as they sometimes project above the general surface owing to superior hardness. In many parts dykes are enormously abundant, and they vary from a fraction of an inch to hundreds of yards in width. It may perhaps be mentioned here that many mineral veins, as described under ORE-DEPOSITS, are of essentially similar form and nature, and the study of dykes and other masses of unmineralized igneous rock has thrown much light on problems connected with the mining of metalliferous deposits of similar form and sometimes of analogous origin.

It appears then that when the strata, or what a miner would call the "country rock," are horizontal or nearly so, the forms assumed by intrusions are very simple, and their classification is easy ; but in areas where there has been much disturbance, a great variety is possible.

It may be noted that when the rocks are faulted intrusions of magma naturally tend to follow the fault-planes, which of neces sity are, as a rule, more or less open fissures. Since faults may be inclined at any angle to the vertical it is sometimes difficult to decide whether a particular intrusion should be called a dyke or a sill, though there is usually more analogy to the dyke form, since faults very often cut across bedding-planes.

Phacoliths.—An important and common occurrence is an in trusion in folded rocks; and here the position of planes of weak ness is the deciding factor. Taking the common case where the rocks are thrown into a series of fairly gentle anticlines and syn clines( see FOLDS), it is clear that there will be a tendency to gape at the tops of the anticlines, as there the rocks are stretched, while at the bottoms of the synclines they are compressed. Hence magma will tend to spread along the tops of the anticline in a long narrow strip, convex upwards and concave downwards, with an indefinite extension along the top of the fold. Such structures are called by geologists phacoliths and by miners saddle-reefs. The gold-bearing saddle-reefs of Bendigo, Victoria, though per haps not of direct igneous origin, are a well-known example of thy form. Occasionally similar shaped bodies, but of course, inverted, are found in the bottoms of synclines.

When dealing with regions of really complex folding, it becomes quite impossible to lay down any rules as to the shapes assumed by intrusions. Owing to accidental variations in the position of planes of weakness, due to special causes, the intrusion may assume most complicated forms, each of which has to be dealt with on its own merits. Again in certain cases the magma, in stead of occupying a definite, clearly bounded space, may per meate a whole region in thin sheets and veins, sometimes of microscopic dimensions, following planes of bedding or cleavage or cracks produced by fracturing of the crust. When the magma mainly follows planes of bedding or foliation in thin sheets the whole effect is described as lit-par-lit injection.

Inspection of a geological map of almost any highly disturbed region will show masses in a great variety of forms coloured as igneous rock. Some are clearly sill-like, while others may be interpreted as dykes. Often however large masses will be ob served with a more or less circular outline, many being necks (q.v.), viz., the pipes or conduits of volcanoes that have long been worn away.

Bosses and Stocks.—It is also evident that many masses of igneous rock, similar in plan on the present surface, never did reach the open air. The mechanics of their formation are difficult to explain, more especially since it is usually impossible to de termine the true form of their underground extension. Many of them however seem to have very steep margins and to be more or less plug-like in general shape; such are usually described as stocks or bosses. The meaning of neither of these terms is very clear, and the whole subject of the origin of the masses is in an unsatisfactory state. The nature of the downward extension is a matter of practical importance, since ore-bodies are often found at the margins of intrusions of this type, which have usually been formed under rather deep-seated conditions. Some remark able circular occurrences of igneous rock, such as the granites of western Cornwall, are now regarded as domes or cupolas formed as subsidiary features on the top of a great batholith underlying the whole region. The ores of tin and other valuable metals show a tendency to accumulate in and around such cupolas, as has also been observed in many parts of western America. For further particulars see LACCOLITH and BATHOLITH.