Modern European Glass

MODERN EUROPEAN GLASS Like every other branch of industrial art the production of glass suffered neglect during the i9th century. The last ripples of the Empire period and the times of Biedermeier occasionally produced a valuable specimen, but then the effort seemed completely spent. When ornamental glass was mentioned, people thought of the heavy cut glass, of which the Bohemian factories and those of Baccarat in France and of Val-Saint-Lambert in Belgium had the monopoly. It was not until the general revival after the middle of the i9th century that there came a renaissance in this sphere. The pioneer was the Frenchman Galle, but his work aimed at a treatment of the glass-material altogether different from that fol lowed in the course of the previous centuries. He produced opaque coloured glass. About the same period the Viennese firm of Lobmeyr attempted to raise the standard of Bohemian glass by perfecting methods of cutting and engraving. Old models, how ever, were closely followed and as a result a development in a modernist direction did not become noticeable until the 2oth cen tury, when, under the influence of young Austrian craftsmen like Hoffmann and those of the Wiener Werkstatte, new shapes and decorations gradually became more general and even spread to the German glass-industry. This renaissance movement had an in fluence also on the Italian (i.e., the Venetian) glass industry, but their excellent products remained too faithful to the shapes typical of the Venetian efflorescence. But the 2oth century saw a consid erable general improvement. Almost every centre of glass pro duction has tried, in the course of recent years, to apply to the principles of modern industrial art. Important progress in this direction was made by the Swedish factory at Orrefors, which produces cut and engraved blown glass. The French movement continued to be of importance, while in Holland the glass-factory of Leerdam made important experiments which are particularly significant because they make a modern use of all the technical possibilities of industrial glass-making. Before going into details about this development in various countries, a brief reference to certain technical details should be given.

Materials and Treatment.—In the first place it should be noted that glass can be grouped into three divisions according to the elements which are fused together to form it. There is, first of all, glass made with soda and lime, which is utilized for ordinary household articles and for window panes. There is, furthermore, potash and lime glass, which provides the "metal" for fine glass work ; and, finally, lead glass, which is the same as crystal, and is distinguished by a particular lustre and brilliancy of colour.

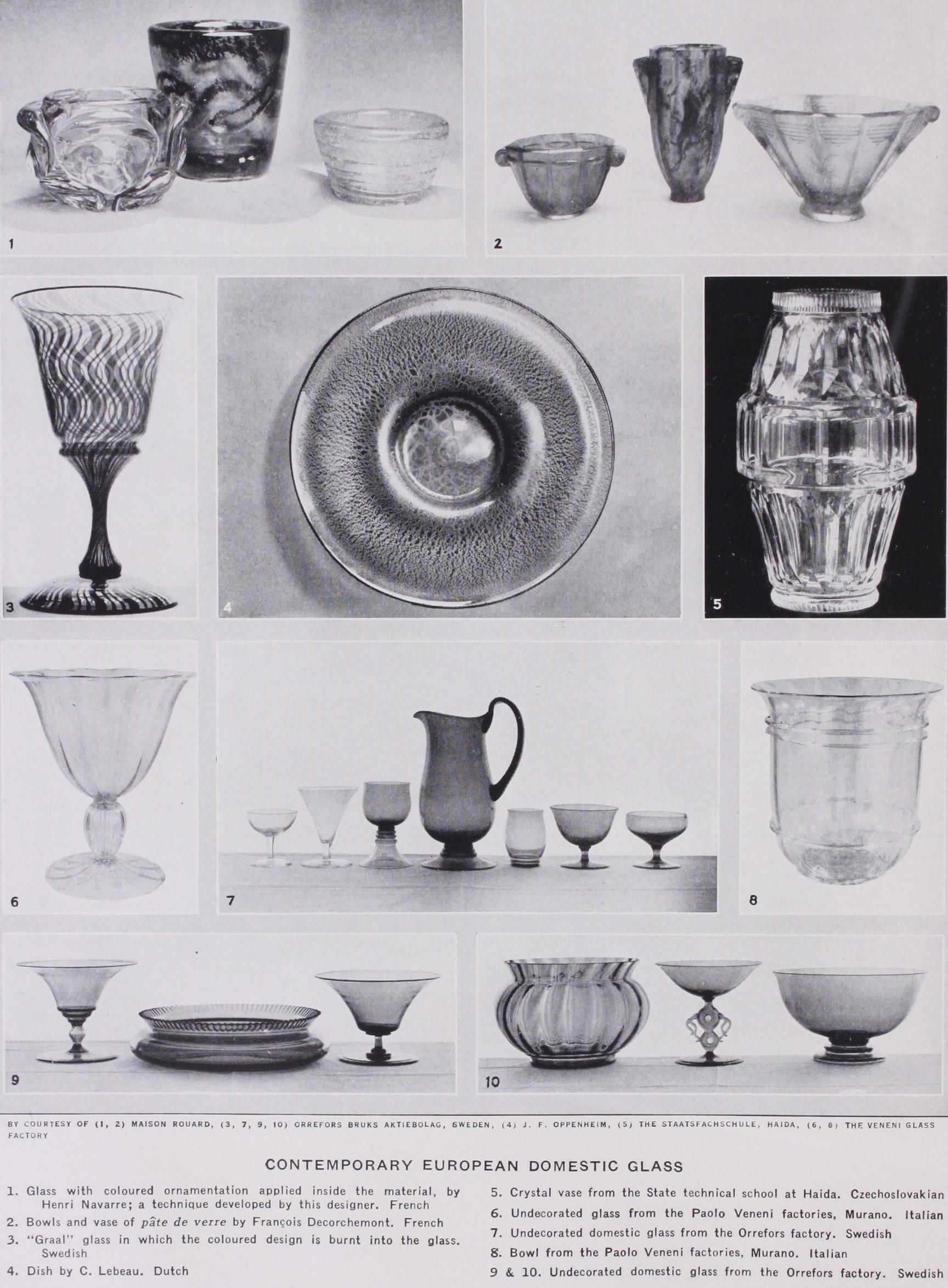

Glass can be submitted to manipulations of different kinds in order to enhance the beauty of the object made from it. To begin with, glass can be blown into a mould or into a series of moulds of gradually differing shapes. To this class belongs the so-called "optic" glass, which is obtained by making vertical dents in the shape. These dents may become the basis of an ornamental motif. Next, there is the ancient Venetian method which applies orna ments by means of threads, blobs and festoons of glass. There is, furthermore, the colouring of the glass mass, which can be effected without impairing the translucency of the glass, and also the methods of covering the glass surface with ice-flowers, and of crackling the surface.

It is technically possible to blow two layers of glass one above the other. The most striking form of this process is the so-called Ueberfangglas which super-imposes two layers of different colours. When both layers are of the same colour, ornaments can be applied in between the two. It is a very subtle and difficult process, but it can be effected successfully where technical ability is allied to artistry. Colour, as enamel, can also be burnt into the glass while it is in the annealing furnace, which makes it possible to apply all kinds of ornaments to the basic material.

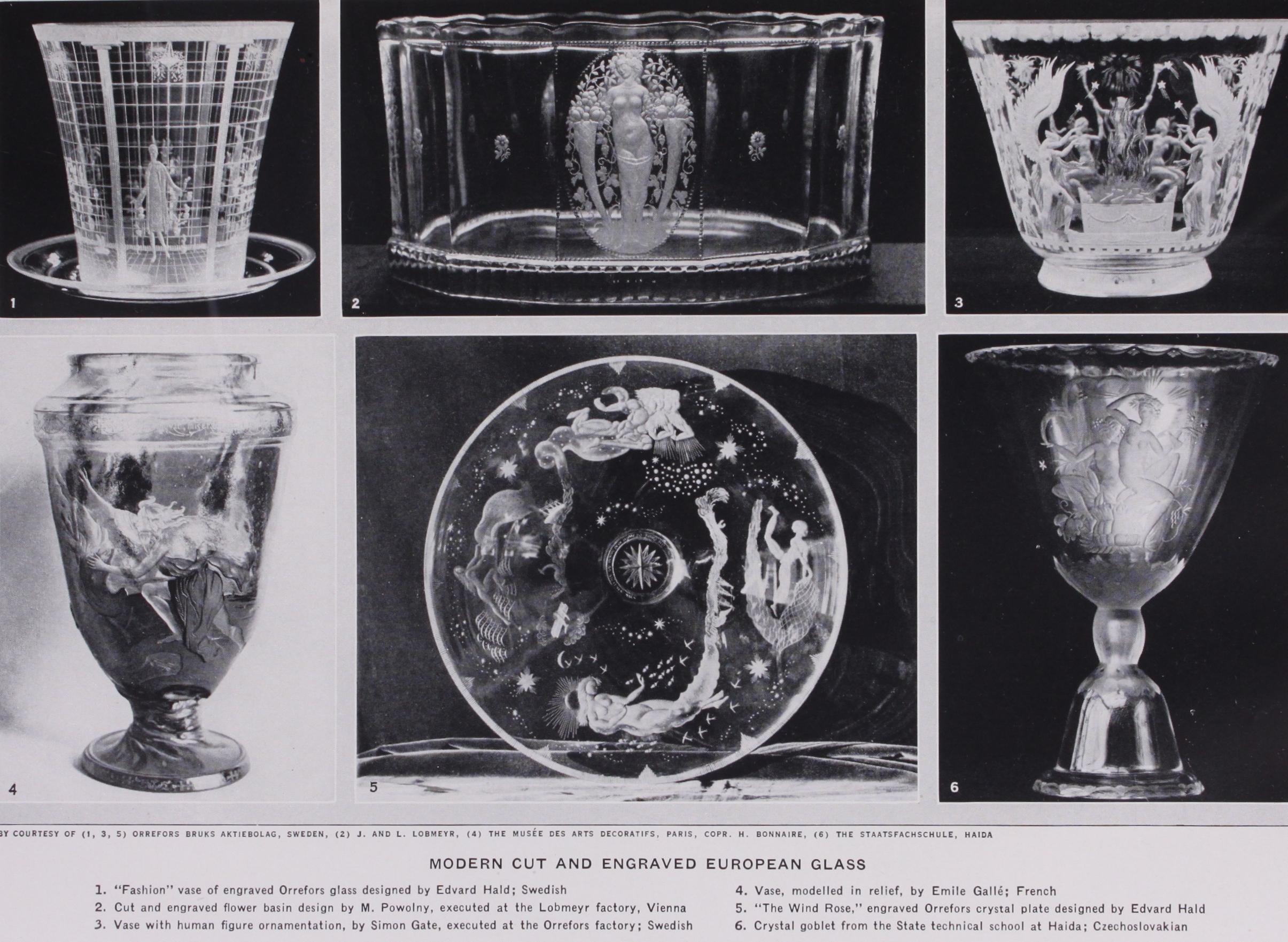

There are two methods of cutting glass. Diamonds or facets can be cut into the glass on smooth iron discs by means of sand or cutting-powder. The rough surface must then be polished on discs covered with leather, felt, or wood. The other method is the cutting of figures by means of the "amaril" wheel. In this process the object must be held in the hand and put into contact with the fixed rotating wheel, while damp sand or powder must be con tinually applied. It is not possible to see precisely what one is doing and a steady hand and considerable ability are therefore required. When applied to Ueberfangglas the effect can be obtained by allowing the differently coloured under-layer to be come visible through the top layer. The modern practitioner of industrial art has found it difficult to adapt cutting and especially engraving to modern conceptions, but even this has in the end been done with success in Czechoslovakia and in Sweden—the cut glass of Hoffman is among the best glass that has ever been produced. The old method of glass engraving by means of a diamond is no longer used. At present the glass, which has been covered with a layer of wax or lacquer, is etched with hydrofluoric acid. A few French artists allow the process to go so far that they obtain differences of surface of as much as io millimetres. A technique of an entirely different kind is that of the pate-de-verre. Glass powder, which has been finely ground, is baked in moulds with or without the addition of various colour oxides. This treatment is allied to that of the ceramist. Considerable care must be observed both in heating and in annealing. Among the methods which are suitable for mechanical application there is also that which con sists in pressing glass, mostly coloured glass, into moulds. It is applied by artists for the production of household articles. The effect of the smooth sides is not so pleasant as that obtained by cutting, but the method is so much cheaper that it enables many people to acquire products of excellent quality which would other wise be beyond their means.

Belgfum.

In the i 7 th century Liége was the centre of the glass industry, but it almost completely lost its importance in the course of the 18th century, and at the beginning of the 19th cen tury Liege glass had no particular significance—at any rate from the artistic point of view. Like Liége, Namur had at that period but one glass furnace where fine glass was still made. It belonged to the Zoude family. In the course of the i 9th century, crystal manufacture began to flourish in the neighbouring Val-Saint Lambert. The produce of this factory is scarcely distinguishable artistically from that of the ordinary crystal factories, although recently a few pieces of good shape and rational ornamentation have been produced. K. Graffart has executed some engraved work which is not without merit. In the industrial area of central Bel gium the Verreries du Centre at Houdeng-Coegnies produce vases and household articles which can stand comparison with the products of Val-Saint-Lambert.Holland.—During the last quarter of the i 9th century the idea of making household articles which should be beautiful came into its own, and its protagonists turned their thoughts to glass. The architect H. P. Berlage occupied a prominent place in this movement. In 190o he designed a set of table-glass which was executed in the French factory of Baccarat. About the same period a member of an old firm of Amsterdam glass merchants, Gerard Muller, made his own designs for household glass. Since then numerous glass sets of his design, usually executed in the Josefinen hutte at Schreiberhau, have appeared, and they are noticeable by the purity of their shape and by their noble simplicity. A drinking service of his design, with hollow blown foot and large bowl, which he has christened "Cyrano," is very beautiful and has an entirely original shape. Each object in this set has been specially con structed with a special view to the purpose for which it is intended. There are also from him bowls and dishes with facet cutting which are striking by their simplicity and dignity.

It is, however, at the big glass factory of Leerdam that the richest unfolding of the possibilities of artistic glass is found. This factory, formerly directed by Jeeckel-Mijnssen, is now under the control of P. M. Cochius. Its activity started when the archi tect K. P. C. de Bazel was commissioned to design a drinking service. De Bazel, whose delicate art is revealed not only in his architecture, but also in his furniture designs, felt particularly at tracted by the brittle material which is glass, and until his death in 1923 his activity in this new sphere continually increased. He designed some ten different drinking-services, all of which excel by their delicate and slender shape. Some of them are very sim ple ; the later types are richer in shape, while minute but care fully considered cutting gives them real dignity. The services in clude not only glasses, goblets and carafes, but also finger-bowls, dishes and flower vases. De Bazel has also designed individual flower vases of a pleasant though particularly practical shape. He has also produced four memorial cups in crystal (jaarbekers, dated 1918, 1919, 192o and 1924), with engraved inscriptions. That of 1924 in particular, executed in cut crystal of dark purple hue, is a noble piece of work. The inscription round the rim is dull gilt and reads worstelend waakzaam (wakeful and struggling). He also made designs for a complete service in pressed glass, en tirely constructed upon a regular decagon, which is being brought into trade in blue, brown, purple and green.

In 1923, Dr. H. P. Berlage designed a breakfast-service, severely constructed in yellow-coloured pressed glass, while he also de signed a few of the dated annual cups, among which that of 1925 is distinguished by a shape which is at once monumental and slender.

Since 1917 the decorative artist C. deLorm has produced drink ing-sen ices and other table-glass. His work is distinguished by the fullest attention to all the requirements of utility without im pairing in the least the aesthetic value of the article. The artist A. D. Copier has been on the staff of the factory since 1923. He started with two drinking-services inspired by the shapes of flowers and fruit, and he extended his activity over the whole sphere of household glass. His work has resulted in the production of a large variety of bowls, vases and cups, executed in different col ours, which have favourably influenced the general taste in Hol land. Not less well shaped, and decidedly more striking and personal, are similar articles designed by the decorative artist C. Lebeau, who has also worked at Leerdam. Followed by Copier, he started another line of activity by producing specimens of deco rative art, as "Unica." Lebeau's work at Leerdam lasted only a time, and he then went to the Moser factory at Winterberg, while Copier continued to work at Leerdam. The activity of these two artists has produced a rich variety of all kinds of glass-work of a much higher quality than has been attained elsewhere. It has placed Dutch glass at the summit of artistic production. Every technical possibility has been exploited : "optic," "crackled," "iced-glass," Ueberfang, "irisation," "colouring," have all been applied singly or in combination. In this kind of work Lebeau has proved himself stronger and more personal than Copier. Copier has, however, sometimes displayed a very tender delicacy. In 1927 the ceramist C. Lanooy and the decorative artist J. Gidding began to execute work for the same factory. While they produce household articles and ornamental glass by means of the above mentioned technical processes, they have re-introduced the method of enamelling by applying colour evenly upon the glass. They use either a few delicate lines or else complete designs, such as fish motives. Much good glass-work may still be expected from these two artists.

Among other Dutch artists who do glass-work we may mention C. Agterberg, who designed glasses and vases which were made in Bohemia, and some very simple drinking- and breakfast-services, ornamented solely with a black enamelled line. J. Jongert and F. van Alphen have turned their attention to the artistic execu tion of bottles and flagons and have proved that in this direction also innovation and improvement can be effected.

Czechoslovakia, Austria and Germany.—The development of the art of glass-making in German-speaking countries must be considered mainly as one whole, because their glass factories, arts and crafts schools, glass-manufacturing centres and artists con tinually exchange both views and personnel one with another. It is difficult therefore to separate Austria and Germany; while Czechoslovakia, which has so many glass factories within its borders and near its frontiers, cannot be entirely separated from the other two countries.

The application to glass of the new conceptions of industrial art took place in German-speaking countries only at a late period. Originally it was limited to the designing of drinking-services, a matter to which numerous architects and decorative artists have given their attention. Among the long list of names which can be found in Pazaurek's book we shall only mention Peter Behrens, K. Koepping, Kolo Moser, T. Schmuz-Bauditz and W. v. Wersin. Little is observable of attempts to endow other glass products with a particular value resulting exclusively from shape. One might at most reckon among such attempts the objects designed for the Deutsche Werkstatte in Munich by K. Rehm and Else Vietor, by Wolfgang and Herte von Wersin, about the years 1910-14. This work was also partly executed at Murano. However meritorious in many respects, it remained too solidly linked up with Venetian traditions. It is for that reason that more importance attaches to a strongly developed movement in these countries whose aim was the improvement of cut and engraved glass—an aim which has naturally resulted in improvements of shape. Ludwig Lobmeyr was one of the pioneers of this movement. He was at the head of a Viennese glass factory which has been in existence for over a century. As early as 187o he secured the collaboration of good Viennese artists for the design of his more important pieces. So far as shape was concerned, his products continued to be severely limited to the imitation of models from the Italian Renaissance. Yet even in the direction of shape a certain independence was manifest. The main significance of the movement was that work was done in one definite direction. It was possible for able engrav ers like A. Bohm and K. Pfohl, and more especially K. Pietsch, F. Ullmann and F. Knochel, who were entrusted with the execution of these designs, to practise upon good work, until a tradition was established which has greatly benefitted work of a more personal character. We meet with this tradition in the glass factories of Haida, Schreiberhau and elsewhere, as a result of the work of the excellent technical schools of Steinschonau and Haida, in the region of Lausitz, while the school of Zwiesel in eastern Bavaria has a particular significance for the glass districts of Bavaria.

The technical school of Steinschonau dates from the year 1856. H. Zoff, who directed the school from 1899 to 1914, and A. Beckert who became director in 1918, have exercised a great in fluence on the glass produced in the area. The latter especially is a very able designer of glass ornamentations, which are executed at the school. Among the good glass-engravers who have been trained there and have produced the best pieces for the factories of the surrounding area we may mention F. Ullmann (1846-1921), who worked with Lobmeyr from 1887; A. Helzel, and various members of the family Pietsch. Frederic Pietsch works for the firm of Conrad and Liebsch, which executes numerous designs made by this school. The same thing is done by the firm Lorenz Brothers, which furthermore executes work by Munich artists such as P. Emmerich and P. Siisz. The technical school of Haida is much younger. It was established in 187o, and became im portant under the direction of D. Hartl in 1881, and still more so under that of H. Strehblow. This school, which has on its staff ex cellent men such as R. Cizek and J. Schroder, is a source of in spiration to the numerous glass factories within its area; not only does it produce a number of well-trained and expert technicians, but it also provides good designs which are executed at, among others, the factories of J. Oertel and, especially, C. Hosch. K. Hosch made glasses designed by C. J. Pohl, coloured black with cut and engraved ornamentation. J. OerteI also executes designs for the Wiener Werkstatte.

In other parts of Czechoslovakia, which is so rich in glass-mak ing centres, attention is attracted by the artistic glass of the Klostermuhle factory, which belongs to the firm of Utz, where good work was being done about 190o under the management of von Spaun; and by the factories of L. Moser at Meierhofen, near Karlsbad, and at Winterberg, where, especially in the latter, fine glass has been made recently by the Dutchman C. Lebeau. Since the revolution Prague has acquired a considerable importance. At its school for industrial art, the teacher Josef Drahonovski guides the development of the factories by his designs, among which there have been very beautiful ornamental cups, one being a present from the Sokol Gymnastics club to President Masaryk. Other work of value is being done by Kotera and, especially, by J. Horejc for the Viennese glass firm of J. and L. Lobmeyr. This firm of Lobmeyr has set the tone in Vienna for more than a cen tury and has done very much for the revival of artistic glass, but until the beginning of the loth century its productions were mainly commissions in imitation of famous models and motives, particu larly those of the Italian Renaissance. Since then a change has come. The development in a modern direction is due to the firms of Bakalowitz and of J. Lotz Witwe. These two houses collected the younger artists, among them Kolo Moser, the most important of them, who has since died. The Arts and Crafts school, which received its impetus from Josef Hoffmann and to which belonged O. Dietrich, U. Janke, H. Jungnickel and D. Peche, had much influence on Viennese glass. The noted glass artist M. Powolny belongs to this school. He is the most important of them all. Hoffmann has designed coloured glass models of a strong and forceful character that are cut in square facets. The glass of Peche on the other hand is full of airy playfulness. Powolny combines strength of shape and of cut with extremely delicate en graving. Hoffmann and his school, as well as Powolny, have also designed glass for the Wiener Werkstatte. Among their pupils a few women artists of delicate taste deserve mention, viz.: M. Flogel, A. Schroder and V. Wieselthier. There are also artists like J. Zimpel and O. Haerdtl. At present most of them also work for Lobmeyr, while the Bimini-Werkstatte produces fine blown glass after designs by J. Berger and F. Lampl.

The revolution having made connections with the glass factories of Czechoslovakia much more difficult, the Edelglaswerke of L. Forstner,.a pupil of Kolo Moser, founded in Stockerau, has ac quired considerable importance, and has produced beautiful work in cut "copper-ruby" glass and in different kinds of Ueberfang glass.

Finally,

a brief word about Germany. In the north-east of Bavaria, the Arts and Crafts school of Zwiesel, under the direc tion of B. Mauder, is the principal centre. While cut and engraved white glass is the main glass product of Czechoslovakia, Bavaria concerns itself chiefly with painted coloured glass, although en graving is also carried on there, in particular, after designs by Mauder and A. Pech. In Silesia the school of Breslau, under S. Haertl, is of importance, while in Stuttgart the very able teacher W. von Eiff, an extremely proficient glass-engraver, exercises con siderable influence.Italy.—Italian glass owes the prominent position which it occupied until the end of the i 7th century to the workshops of the little island of Murano near Venice, where this industry was con centrated. But after this period of efflorescence Venetian glass fell from the first rank and, notwithstanding attempts at revival, it has not reconquered its former position even in the 19th and 2oth centuries. This is because these efforts, especially those of Salviatti, aimed in the main at continuing the old manner of the glorious period. A certain improvement, no doubt, was obtained, owing to the fact that over-elaborate ornamentation was aban doned and simpler and severer lines were adopted. This is espe cially due to the factories of Paulo Veneni, where the designers Francesco Zecchin and Napoleone Martinuzzi are at work. But up to the present they do not seem to have freed themselves from the domination of old models, as regards either colour or shape. Work of a really personal character is still rare, however able and technically perfect the products may be.

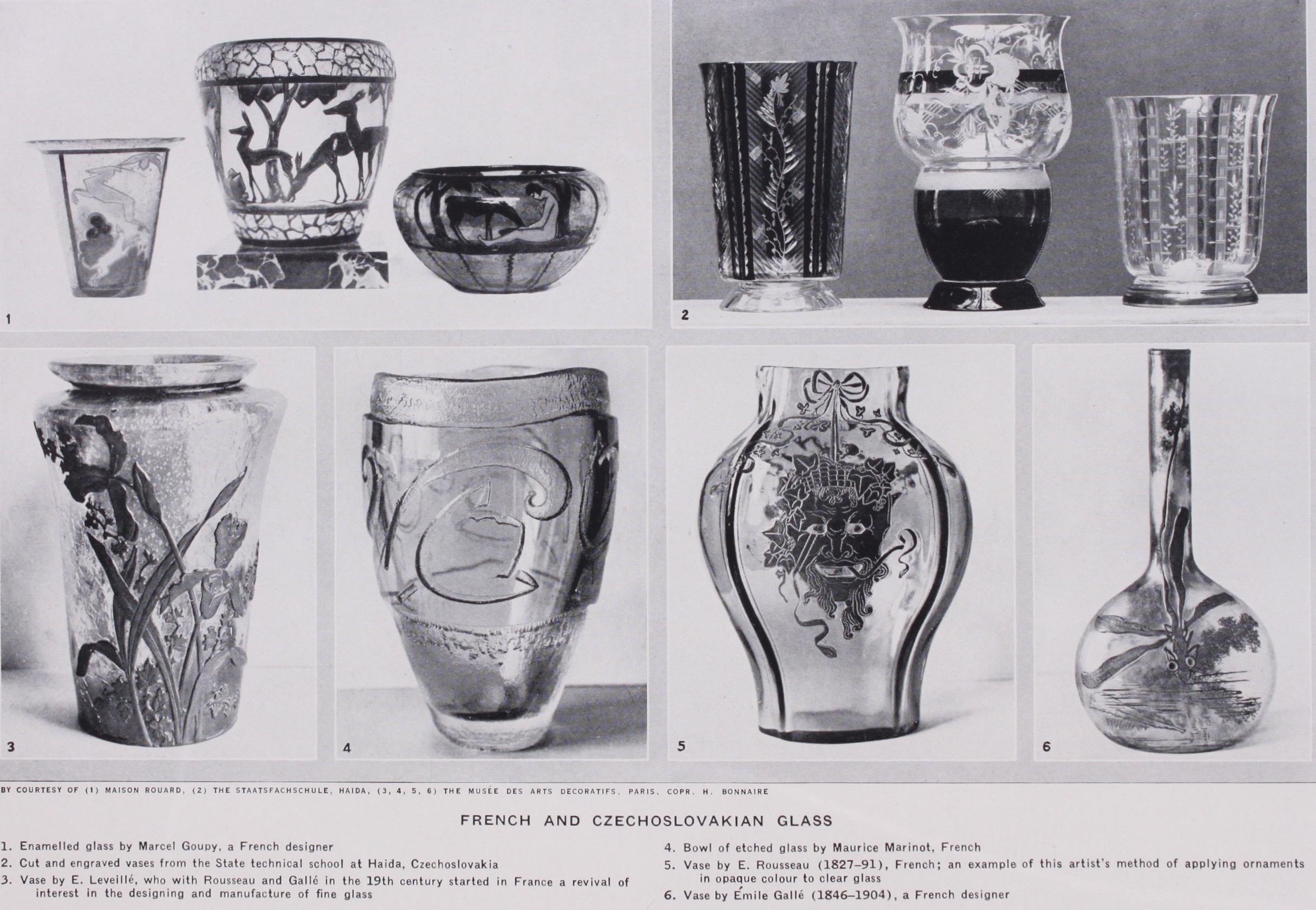

France.—The revival in France came in the days of the World Exhibition at Paris in 1870, not from the old glass factories but from the fine handwork of enthusiastic artists. The first of these is Th. J. Brocard, who set himself to imitate the old art of the followers of Islam, and succeeded in imitating them very closely. He made enamelled and coloured glasses, mosque-lamps, etc., as well as imitations of 16th century German goblets, in which he displayed a high technical aptitude. At the same time, E. Rous seau and E. Galle were busy and soon created general admiration by their original work, shown at the exhibitions of applied arts in 1884. A third artist, E. Leveille, soon followed in practically the same direction.

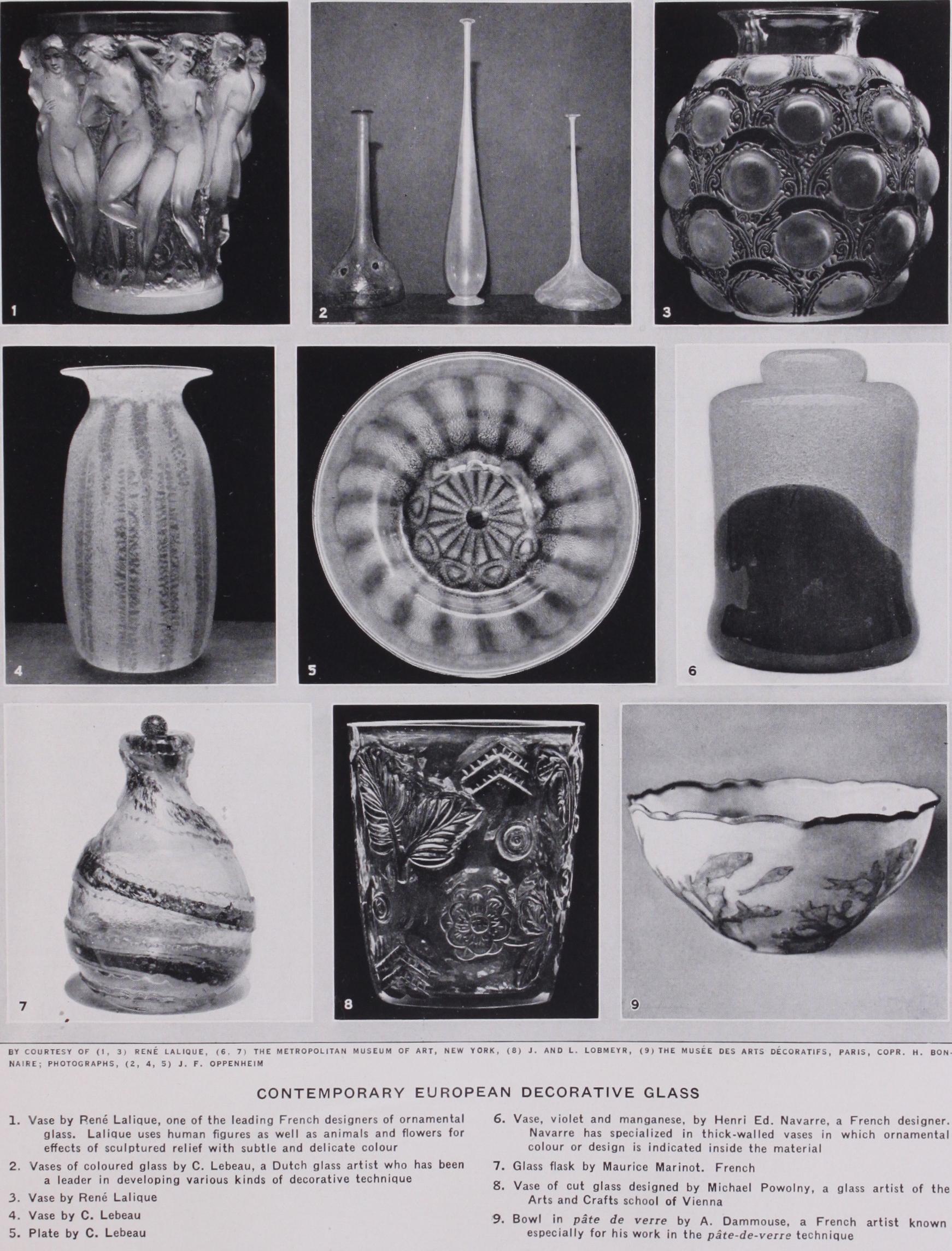

E. Rousseau (b. 1827), originally a ceramist, was seized, fairly late in life, by a passion for glass. If his assiduous search did not always lead to new methods, his results were often most unex pected. His system of applying opaque-coloured ornaments on clear and transparent glass was something very striking. Equally novel was his way of producing a play of colour by introducing into the volume of the clear glass metal-oxides or glass dust. In 1885 he started a collaboration with Leveille, who after Rous seau's death in 1891, continued to work in his tradition. Good samples of the work of both artists can be seen in the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris. In many respects they are the im mediate predecessors of such very modern workers as Marinot. At the outset, however, their fame was obscured by that of Emile Galle, born at Nancy in 1846. After having learned his craft abroad, Galle established a glass factory in his birthplace in 1874. His first attempts aimed at giving colour to his material without causing it to lose its transparency. He first produced a blue colour by means of cobalt-oxides, which was the great success of the ex hibition of 1878. Afterwards he succeeded in applying numerous other colours. There is at the Museum of Decorative Arts a very beautiful vase, dating from 1884, with ornamentations in green and black in the clear glass, which is modelled in relief. In 1889 he was able to announce that he could apply all colours from orange or lacquer-red to violet and purple. He also practised glass-en graving. Originally he disapproved of the use of acids, but gradu ally he gave up this attitude, and started researches into the pro duction of coloured opaque glass with etched ornaments and of glass in double layers, with the ornamentation cut into the outer layer. About 1897 he was melting into his glass pieces of other glass or enamels of a different colour. Finally he devoted his efforts to the search for the so-called pate de verre, in which others were to follow him with more success. His contributions were novel in many respects as regards the material used, but in shaping his form he was not always equally happy—whenever his shapes are not extremely simple they become disagreeable. over-burdened with flower-ornamentations or even altogether in the form of flowers. The leading place left open by Galle was taken over by Rene Lalique, originally a designer of small ornaments, who soon after the exhibition of 190o devoted himself to the making of glass. Although Galle had also designed household glass, he aimed mainly at the production of unique pieces by the application of diverse and difficult technical methods. Lalique, on the other hand, applied to his work all the resources of modern mechanical pro duction. The application of enamels and engraving by means of the wheel have become exceptional. The usual process now is that of moulding or blowing into set matrices. This is consider ably more expensive and therefore necessitates mass production.

The system of moulding allows three main combinations : (a) The decoration can be applied completely or partly in relief to the object; it can then be enamelled (i.e., coloured) or rendered mat by cutting. (b) The decoration can be pressed into the object in bas-relief, thereby heightening the illusion owing to its greater transparency. (c) The whole object is covered with a decoration which is enamelled and cut either mat or polished.

The colour of the glass can also be modified. Lalique usually borrows his decorations from nature (fish, deer, flowers, sometimes human figures). His work aims at pleasant elegance rather than at profundity. For this reason he has given much attention to articles of general utility (perfume flasks, table glass), though he has also executed large decorative works in glass, such as the not very successful fountain of the Esplanade des Invalides, during the exhibition of 1925 in Paris, and also a mural decoration orna mented with fountains in the steamer "Paris." Meanwhile, further work had been devoted to the other glass technique, that of pate de verre. The real initiator of this process was Henri Cros, whose efforts went much further than those of Galle. He was not always equally successful in this difficult work, but his large reliefs, such as those which are now at the Luxem bourg museum, the Victor Hugo museum and the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris, dating from approximately 1892, display a decided skill. An artist who made even more interesting experi ments was A. Dammouse, who in 1898 began work on this process, which is based on a more or less ceramic treatment of glass-pow der. He manufactured vases and goblets, usually of small size, shaped like the calyxes of flowers, softly coloured (blue, purple and yellow-brown), which are notable for their refined delicacy. In 190o his example was followed by G. Despret, who had been at the head of the glass manufacture of Jeumont since 1884. In collaboration with G. Nicolet, Despret made little statues and what-not ornaments. Of more artistic value, however, is the work of F. Decorchemont, who also began as a ceramist and in 1900 followed the example of Dammouse. He made considerable technical progress in obtaining a certain measure of translucency. His vases and cups, coloured dark blue and heavy green, brown or lilac, picturesquely varied by touches of less translucent colour, nearly always bear a geometrical ornamentation on the outside.

For the sake of completeness we may further mention the names of Argy-Rousseau, Walter, and Joachim and Jean Sala (father and son) who also worked in pate de verre. Although frequently not without a certain roughness, their products, as can be seen for instance in their fruit-bowls, possess a picturesqueness which would be more effective if the material were more satis factory.

It is not among the artists of the pate de verre that we must look for the continuation of the glass-tradition of Rousseau, Le veille and Galle, but rather among those who have maintained the process of glass-blowing. Of these the foremost is Maurice Marinot. His followers include P. and A. Daum and Henri Navarre, who works on more original lines. Maurice Marinot started his career as a painter, but a visit to the glass factory of Bar-sur-Seine gave him a predilection for glass-work. He exhibited his first attempts at the Salon des Independants of 1912. Marinot practises the craft in all its stages and handles the blowing-tube himself. He adorned his first glasses with small coloured opaque enamels. His motifs were birds, heads of women, flowers or festoons, with no other significance than a vivid colouring which enhances the transparency of the clear glass. Without altogether abandoning his original methods he afterwards started to shape vases and bottles with very thick walls, in which, round the orna mentation that was usually composed of sharp angular lines, he made fairly deep indentations by treating the glass with acids. The result was to give more unity to the glass and the ornamenta tion. Marinot proceeded further in this direction by producing smooth glass without any exterior ornament, but very thick and ornamented by air bubbles inside the material. The air bubble usually counted as a fault in the old glass-craft, but Marinot made it into an ornament by rhythmic repetition. A further step in this direction is the use of colour-oxides inside the material, by which the glass sometimes is made almost opaque. A factory directed by P. and A. Daum at Nancy started by following Galle's example and produced decidedly satisfactory work. This factory now uses its own designs, shapes and colours, but applies the process of strong indentations obtained by acids which was initiated by Marinot. This work has enough originality and shows enough artistic ability to deserve special mention. Such is equally the case with the work of Henri Navarre, which was represented, for the first time at the exhibition of 1925, by thick-walled vases where inside the material a vaguely indicated, but regular ornamentation in blue, brown or black had been applied. This work was done anonymously for a factory indicated by the letters Umab. When this factory failed, Navarre started independent work in the Verrerie de la Plaine Saint Denis, near Paris. His ornamentation is still applied in the same manner but has acquired more strength.

Another and very able artist in the technique of glass enamelling, who also designs articles of general utility in earthenware and porcelain, is Marcel Goupy, who represents the genuine French taste, which never strays from delicacy. He is undeniably the most gifted among a group of artists in decoration, of whom, in order to be complete, we mention also Maurice Dufrene, Manzana Pissarro, Henri Farge, Simonet and Jean Luce. All these artists also produce household and table-glass which is generally very elegantly shaped. Although the ancient factory of Baccarat has remained on the whole outside modern artistic development, it has entered upon new ways with the production of table-glass de signed by G. Chevalier and A. Bullet. The Verrerie de la Corn pagnie des Cristalleries de Saint Louis produces work designed by Maurice Dufrene.