Defence Navy

DEFENCE: NAVY Historical.—For over i,000 years the Navy of Britain has written the history of a small island people who have developed, by virtue of their power upon the sea, into the senior partner of a great Empire. Details of the British Fleet of to-day are available in text books, but to obtain a true understanding of its traditions, its purpose and its strength, one must glance back through the chief historical events of the past ten centuries. The earliest sea fights in which English ships took part were fought in the years A.D. 833 and A.D. 84o, during the reigns of Ecgbert and Ethelwulf, the first kings of England. The invasions of the Norsemen forced the English people to defend themselves by some form of national organization and each shire was called upon to provide ships in proportion to its size and wealth. These ships were inferior to those of the vikings who held the upper hand until Alfred the Great (A.D. 8 71-90 i ), with his powerful newly built fleet, defeated them in A.D. 878. Alfred's ships, which were the first "King's Ships," were swifter, steadier and higher out of the water than those of the Norsemen and some had as many as sixty oars. The same means of providing a navy was employed by Alfred's suc cessors, that is a few ships which were the private property of the king were reinforced by the ships of the shires, and later by a feudal contribution from certain privileged coastal towns.

The Norman Conquest.

Up till the time of the Norman Conquest little development took place in the ships. They were large open boats, long and narrow, propelled by from 3o to 6o oars with a square sail for use when winds were favourable. Fur ther protection was obtained by arranging the shields of the soldiers along the bulwarks. Such was the "Mora" in which William the Conqueror came to England in io66. The Norman kings made no great change in the organization of their navy. The king's ships, the forerunners of the national navy of today, formed the chief fighting force. The coastal counties or shires were required to supply, when called upon, ships for the king's service, fully manned and equipped. Bailiffs or port reeves were appointed who kept a strict account of all ships in their areas and it was their duty to see that they arrived at the rendezvous appointed by the king. This system whereby the coastal towns bore some of the responsibility for the naval defence of the realm, remained in force until the I7th century. A third source of supply was obtained by granting privileges to certain seaport towns, who in return, as a feudal contribution, maintained a certain number of ships, ready to supplement the king's ships. Of these the Cinque Ports (q.v.) were the most important and from the i i th to the 13th centuries they played a prominent part. They were always inclined to piracy amongst themselves and at the expense of other English seaport towns. This brought about their downfall and by the time of Edward III. (13 2 7-7 7) they had ceased to form part of the national sea defences.The number of the king's ships varied from time to time. In 1205, King John maintained a fleet of 5o galleys or "long ships" in various ports and William of Wrotham, Dean of Taunton, was appointed "keeper of the king's ships," the first record of any form of central administration of naval affairs. During the time of the Crusades in the i 2th and i3th centuries, the fighting ships, built solely for battle, still retained the form of the long, narrow, swift galley propelled by oars alone: or if rigged with a mast and sail these were removed before going into action. The larger and clumsier merchant ships of this period had a permanent mast and square sail and relied upon oars as a secondary means of propul sion. When prepared for war these ships were fitted with built up castles at each end from which missiles could be thrown into any ship alongside. In time the ships became rounder in shape with built-in fighting castles, and relied almost entirely upon an ele mentary form of sail, with only one mast. By the beginning of the reign of Edward III. (13 2 7) the fighting galley had almost disappeared from the English fleet, and the ships which defeated the French at Sluys in 134o and the Spaniards off Winchelsea ten years later were sailing ships only.

The Plantagenet Navy.

Until towards the end of the 14th Century the English Navy was successful upon the Narrow Seas and suffered no real reverse. King John claimed the sovereignty of the seas after the destruction of the French Fleet at Damme in Flanders in 1213: his successors upheld the claim but Edward III. was the first king to enforce it. In the declining years of his reign, however, and during the troublous times of Richard II. the navy was neglected and fell into decay. Soon after Henry IV. (1399-1413) came to the throne, the southern coast of England was ravaged by the French. The country was dis tracted by internal wars and there were no king's ships to form a defence. So desperate was the position that the king was forced in 1406-07 to call upon the merchant shipowners to provide ships to defend the realm. This saved the situation for the time but it was not until after the accession of Henry V. (1413-22) that the prestige of England was re-established upon the sea. He re organized and rebuilt his fleet, with it he drove the Genoese allies of France out of the channel and by its aid before his death became the virtual master of France.Gunpowder was invented in the beginning of the 14th century but it was not until the end of the century that guns began to be used afloat, and the first record of an English ship carrying guns is in a ship called the "Christopher of the Tower" in 1410. The guns were very small, designed as mankillers rather than to damage the structure of the ships, and they were mounted in embrasures in the forward and after castles. The necessity of carrying many guns led to an increase in the size of warships and some of the ships built by Henry V. were of nearly i,000 tons.

In spite of the troublous times of the Wars of the Roses, the English fleet maintained the command of the Narrow Seas and slow but steady progress was made in the construction and rig of the ships. By the end of the reign of Edward IV. (1461-83) the English ships had developed to the standard of those of the Mediterranean powers. They carried three to four masts and a bowsprit and set as many as six sails, but the hulls, though larger and better built, did not differ in shape from the ships of a century earlier.

The Tudor Navy.

The reign of Henry VII. (1485-1509) marked the real beginning of England's sea power. The voyages of Columbus, Vasco da Gama and the Cabots, in the last decade of the 15th century had startled the old world and turned the attention of all maritime nations towards the possibilities of overseas trade. Under the influence of Henry VII. the English nation ceased to be merely an island people, concerned only with coastwise traffic, and began to develop into a hardy race of sea men who took the English ships through the seas of the world. The king subsidized private enterprise and trade and built great ships such as the "Regent" and "Sovereign," and he constructed the first drydock at Portsmouth. These ships were armed mer chantmen, capable of carrying large cargoes, and the "Regent" is said to have carried 225 small breechloading guns. At about this time great strides were made in the size and power of artillery and the heavy muzzle loading gun was invented. Henry VIII. took the keenest interest in his fleet and armed his ships with this new and heavy ordnance, thus introducing an entirely new factor into naval warfare. The guns were so heavy that they had to be mounted on the lower or cargo decks. Holes were cut in the ship's sides for the guns to fire through and so began the development of the fighting ship capable of firing broadsides to damage the hull and rigging of the enemy. The ships of Henry VIII., unlike those of his father, were built ex clusively as fighting ships, and soon after he came to the throne the "Mary Rose," the first of the long line of British battleships, was laid down. Henry had ample funds from the plunder of the Church and he laid down 85 "kings ships," great and small. Of these the "Henri Grace a Dieu" or "Great Harry" was the most magnificent and powerful ship of her time, and carried heavy ordnance on her lower decks and a large number of smaller guns in her upperworks.Henry VIII. formed the first central navy office for the ad ministration of the fleet. His navy board, constituted by letters patent on April 24, 1546, consisted of a lieutenant of the ad miralty, a treasurer, a comptroller, a surveyor, a clerk of the ships and other minor officials. The Board was charged with the building and the upkeep of the ships and with the supply of stores, victuals and pay. The Lord High Admiral (or later the commissioners for executing that office) had complete political and military control over the fleet and issued commissions to its officers, but exercised only a nominal control over the navy board. This dual system of government of the navy remained in force, with the addition of various departments, until after. the close of the Napoleonic Wars. The records of the time are in complete, but as far as can be ascertained, the navy at the end of the reign of Henry VIII. consisted of 53 ships of a total of 11,270 tons, armed with 2,185 guns and manned by 3,00o men, more than half of whom were soldiers.

The Elizabethan Navy.

During the disturbed reigns of Ed ward VI. (1547-53) and Mary (1553-8) the navy was reduced to a bad state. Edward VI. did his best to develop the growing seaborne trade of the country and took the first steps towards ex pelling the Hansa Merchants, but the navy was neglected, and Mary, through lack of sea power, was unable to hold Calais. Queen Elizabeth (15 58-1603) on her accession at once took steps to restore the navy to the position it had held in the days of her father. During the first twenty years of her reign, al though not at war, she encouraged the exploits of Hawkins, Drake, Frobisher, Raleigh and a score of others on the Spanish Main and in other parts of the world. Many improvements took place in shipbuilding and in organization. When John Hawkins was placed in charge of the queen's ships in 1577 he introduced a new plan of shipbuilding by increasing the length of the ships in pro portion to their beam. This produced ships completely out classing their predecessors in speed and sailing qualities and carrying more guns upon the broadside. The "Revenge," the first ship completed upon the new plan was so successful that numbers of the old ships were rebuilt upon the same lines. It was with ships of the new type that Drake, in his expedition to Cadiz in 1587 "singed the King of Spain's beard." Taking only four ships into the harbour he engaged and quickly defeated the whole fleet of Spanish galleons who were totally unable to withstand the broadside fire of the heavy ordnance of the English ships. This battle established the "broadside battleship" as the fighting ship of the future and sounded the death knell of the oar pro pelled galleon that had held sway in the Mediterranean for 1,000 years.Two notable advances in organisation of the personnel marked this period. In 1582 a graduated scale of pay for officers and men was, for the first time, introduced and a fund was started for the relief of sick and wounded seamen. All men employed in the navy were subject to a small deduction from their pay which was paid into the famous "Chatham Chest." This fund was administered by the commissioner of Chatham dockyard and by four other commissioners elected by the seamen.

The Cadiz Expedition postponed the threatened Spanish Inva sion of England for a year and in 1588 the Great Armada sailed. It was composed, chiefly, of merchant ships which carried few if any guns. The Spanish ships were short, had tremendous free board and were probably little improvement upon Henry VII.'s "Regent" of 1 oo years before. The English fleet consisted of 34 "queen's ships" and a number of merchant ships, large and small, all more modern than the Spaniards. The superior speed and handiness of the English ships enabled them to choose their own range for their heavy guns and the Great Armada was severely handled during its disastrous week of sailing up Channel. Forced by fireships to move in panic, whilst at anchor off Gravelines the Spaniards were driven into the North Sea by a southwesterly gale. Unable to join the army of the Duke of Parma in the Netherlands, the Armada was chased by the English until their ammunition was exhausted ; scattered by wild weather in the northern seas, only a remnant returned to Spain to tell the sorry tale. During the last fifteen years of Elizabeth's reign the English fleet was uniformly successful and when she died her navy con sisted of 42 ships of 17,00o tons, manned by 8,000 men, more than three-quarters of whom were seamen.

The Stuart Navy.

On his accession James I. (1603-25) made peace with Spain under such humiliating terms that the sea power of England faded until she became almost negligible upon the sea. English ships were forbidden to trade in certain seas or even to defend themselves if attacked, under penalty of being treated as pirates. Despite this, Hudson, Baffin, Raleigh and others showed that English sailors still dared to sail the seas. James was interested in shipbuilding and strongly supported his master shipwright, Phineas Pett, but the king's ships were allowed to go to rack and ruin and the administration was corrupt. The powerful fleet built up during the previous hundred years almost ceased to exist and when a naval expedition was fitted out to attack Cadiz by Charles I. (1625-49), the whole breed of Eliza bethan sailors had disappeared. Military officers commanded the ships and, out of the 1 oo required, only nine of the king's ships were found in a fit condition to serve. The flagship of the expe dition the "Ark Royal" had fought against the Armada and some of the ships carried the same sails that they had used in 1588. Most of the merchant ships requisitioned were in a like case and the expedition was a failure. A similar fate befell two expeditions to the Isle de Re in the attempt to support the Protestant Alliance. These disasters awoke the King to the state of the navy, but the royal revenue being insufficient to rebuild the fleet he levied the Ship Money tax (q.v.). The successive levies of 'this tax, although they laid the basis of the first royal and national fleet, proved to be one of the main causes of the Great Rebellion. In spite of the long period of naval depression, the art of shipbuilding had made great strides and the "Sovereign of the Seas," the first of the "Ship Money" fleet was the finest ship that had ever been built. She carried 1 oo guns arranged in three tiers and was the first of the English "three-deckers." Charles' efforts to rebuild the fleet were of no avail and by 1640 the Dutch had become the greatest sea power and practically drove the English off the sea.

The Commonwealth Navy.

During the Civil War the navy at first supported the parliamentarians, but afterwards joined the royal forces. On the defeat of the royalists the fleet left for Holland, where under Prince Rupert and aided by the Dutch, it ruined English trade. At the beginning of the Commonwealth (1649-6o) no small craft or coasting vessel dared to put to sea from English ports, but in 1649, Robert Blake was given the command at sea and the regeneration of the navy fell into his able hands. In seven years, Blake defeated the royalist fleet under Prince Rupert, the Portuguese, the Dutch, the Algerian pirates and the Spaniards and made the English fleet for the first time a power in the Mediterranean. During the First Dutch war twelve desperate sea fights were fought in which both sides covered themselves with glory and the war ended in favour of Great Britain. In this war Blake found that the merchant ships which supplemented the fleet were untrustworthy in action and thenceforward Parliament built its own ships and supplied its own officers. Codes of fighting instructions and of discipline were published that formed the basis of the Articles of War most of which still remain in force. Under the Commonwealth 200 war ships were built and the fleet was brought to a high state of efficiency.

The Restoration.

Charles II. did much to encourage the navy, and in the first years of his reign the fleet was used to protect British interests in the distant seas. Squadrons were sent to Bombay and to the West Indies to suppress piracy and Tangier was acquired as a base, only to be evacuated in 1685. The term Royal Navy came into use and a permanent corps of officers was formed. Lads of gentle birth were sent to sea to be trained as officers and many other reforms were introduced, but the ill treatment of the crews of the ships caused bitter discontent. James, Duke of York, the Lord High Admiral, was more success ful as an administrator than in command at sea and he was ably assisted by Samuel Pepys (q.v.) as secretary of the Admiralty. But corruption was rife : money voted for the navy was wasted and the outbreak of the second Dutch war in 1665, found the fleet badly equipped. Nevertheless Monk and Prince Rupert won some successes in spite of poor material. The Dutch raid upon the Medway ended a war which was, on the whole, inglorious to England and disastrous to her trade, and the Peace of Breda, signed in 1667, favoured the Dutch. At the outbreak of the third Dutch war (1672-74) the fleet was in an even worse case than before, as Charles had spent all available money upon troops. Parliament refused to vote supplies, the dockyards were denuded of stores and it was with great difficulty that a small fleet was fitted out. The French squadrons, which co-operated with the English fleet proved to be inefficient allies, and the Dutch Admiral De Ruyter was uniformly successful. The war, which ended in 1674, brought little credit to the Navy: but the Netherlands were exhausted and England was left stronger at sea than any other maritime state. During his short reign James II. (1685-88) re tained the control of the navy in his own hands and did much to restore its efficiency. On his flight after the Revolution of 1688, the fleet took no active part in preventing the landing of William III. (1688-1702) . War broke out with France in 1689 and after a small success at Bantry Bay and a defeat off Beachy Head the fleet under Admiral Russell, with the aid of the Dutch, destroyed the French fleet at the battles of Barfleur and Cape La Hogue. The war dragged on for another five years during which the Eng lish fleet constantly raided the French Coast.

The War of Spanish Succession

(q.v.).—Peace was signed at Ryswick in 1697, but it was short lived, for four years later the War of the Spanish Succession broke out. The navy held the command of the Narrow Seas and Marlborough's armies were transported without interference to win the victories of Ramillies, Blenheim and Oudenarde. The ships of England won renown the world over during the reign of Queen Anne (1702-14). Admiral Rooke destroyed the French and Spanish fleets at Vigo in 1702. He defeated the French Toulon fleet off Malaga and, in 1704, he captured Gibraltar, whilst four years later Sir John Leake secured Minorca, after having twice raised the siege of Gibraltar. Shovell, Benbow and Martin all added renown to the British fleet and when in 1713 the Treaty of Utrecht was signed, England retained her position as mistress of the seas.At the death of Queen Anne, the material strength of the navy was 247 ships of 170,000 tons, manned by officers inured by ten years of successful war. The beginning of the Georgian era brought success to the country, but the navy was starved and im poverished. The personnel was neglected, the design of ships became careless and ships in the dockyards were poorly main tained. Parliament reduced the expenditure upon the navy to less than one half, at a time when English responsibilities were increas ing all over the world and the service suffered in all departments from the political corruption of the times.

The War of Austrian Succession.

When the War of the Austrian Succession broke out in 1739, the fleet was in a grave state of inefficiency. Vernon failed utterly before Cartagena in the West Indies and was recalled in disgrace. Matthews, a gallant and able Admiral, did his best in the Mediterranean with an ineffi cient and inexperienced squadron, lacking in frigates and even in supplies. He was recalled, was made the scapegoat of the poli ticians and was dismissed from the service with disgrace. Anson was sent on a voyage round the world with six small ships and sailed for South America in 174o. His ships were rotten and badly found: his crews were sickly and composed of old pensioners. With indomitable firmness, faced with disaster after disaster, he pressed on with his task and after incredible hardships, he returned four years later with one ship only, the "Centurion." He had harried the Spaniards on the coast of Peru, sailed round the world, had taken an immensely rich prize and brought his booty home. Hawke, Saunders and Byron were among Anson's officers on this voyage, names that made history a few years later. In Anson went to the Admiralty and commenced his long period of successful administration, which laid the foundations of the glories of later years. It was with ships commanded by officers trained by himself that he inflicted a heavy defeat upon the French off Finisterre in 1747, a victory repeated by Hawke off the same place later in the same year. These two victories ended the war and peace was signed at Aix la Chapelle in 1748.In the few years of peace that followed Lord Anson continued his regeneration of the navy. The Naval Discipline Act was re vised and remained unaltered for over a hundred years. Many reforms were introduced, including the formation of the corps of Royal Marines in 1755. The navy office was compelled, for the first time to render accounts to the Admiralty, the dockyards were brought into a state of order and some, at least, of the rampant peculation was stamped out. Amongst the many improvements made in the design and fitting out of ships was the adoption of the practice of coppering the bottoms of the ships, which had a marked effect upon their speed and sea keeping qualities.

The Seven Years' War.

This war which broke out in 1756, opened with the political blunder of sending Byng to the Mediter ranean with an inadequate force, to relieve Minorca. His failure was followed by the tragedy of his court martial and sentence to death. Byng's place was taken by Hawke and many attacks were made upon the French coast towns with varying success. In 1759—the "year of victories"—Hawke and Rodney in the Channel and Boscawen in the Mediterranean frustrated the threat ened French invasion. Lord Hawke won his epic victory over the French fleet in a gale of wind in Quiberon Bay and the strategy of Admiral Saunders in the River St. Lawrence enabled General Wolfe's Army to take Quebec. In the East and in the West Indies the British navy held its own and when in 1763, the war came to an end with the Peace of Paris, England was domi nant on the North American continent and in India, Minorca had been recovered and her navy was supreme upon the seas. There followed twelve years of peace marked by voyages of discovery. Byron, Wallis and Carteret explored the Pacific and Cook made his three great voyages, discovering New Zealand and Australia. The period was, however, marked by the greatest state of corrup tion and incapacity, under the administration of Lord Sandwich, that has ever been known in the annals of the British navy.

The American War of Independence.

The outbreak of the American War of Independence (1775-81) found the fleet in a deplorable condition, with unseaworthy and ill equipped ships dis tributed in weak and unsupported units. The French who had thoroughly reorganized their fleet, joined the revolting colonies in 1779 and inflicted heavy reverses upon the British at sea and by 1780 England found herself at war with France, Spain and Hol land simultaneously. Gibraltar was constantly besieged and in 1776 the American Colonies declared their independence and were able to maintain it. Such was the sorry pass to which the criminal neglect of the navy had brought the country. But Lord Anson's sound administration bore fruit. Parker in the West Indies, Keppel and Kempenfelt in home waters and Hughes in the East Indies, all men trained under Lord Anson, eventually estab lished British supremacy in those seas. Finally, in 1782, Lord Rodney, by his great victory over De Grasse at the Battle of the Saints off Guadaloupe, brought the war with France to a success ful conclusion. The Treaty of Versailles, signed in 1783, was fol lowed by a few years of peace during which every effort was made to maintain the fleet in a state of efficiency. The organisation of the dockyards was thoroughly overhauled and under the admin istration of the younger Pitt, money voted for the upkeep of the fleet was used only for that purpose.

The French Revolutionary Wars.

When the French Revo lutionary wars broke out in 1792 the British ships were fully equipped and ready for sea, manned by skilled officers and men. Howe, Hood, Jervis, Duncan, Cornwallis, Keith, Collingwood and Nelson stand pre-eminent amongst the unsurpassed band of seamen who brought honour to British arms in the years that fol lowed. The war opened by the occupation of Toulon in 1793 by Lord Hood, and in the following year Lord Howe won his sweeping victory over the French fleet on the "Glorious First of June." In 1794, Lord Hood captured Corsica (where Nelson lost his right eye) and in the next year there were actions between the French and British fleets off Genoa, L'Orient and Hyeres; in each case the British were victorious but failed to press home their advantage. By the end of 1796, England again was at war with France, Spain and Holland: the Cape of Good Hope had been captured by Lord Keith, but the British fleet had been withdrawn from the Mediterranean to Gibraltar. In February 1797 the Span ish fleet was heavily defeated off Cape St. Vincent by Admiral John Jervis and Nelson was promoted Rear-admiral.

The Mutiny.

Scarcely had the news of this brilliant victory reached England, than the whole navy broke out into mutiny. Poor pay (it had not been altered since 1649), bad food, the use of the press gang and harsh treatment had for some time been the cause of complaints by the men to the Admirals. These com plaints had been forwarded and neglected by the Government. Matters came to a head at Spithead in April, where the attitude of the men was respectful but firm, as it was also at Plymouth. Reforms were promised, but delays in carrying them out brought on a further outbreak in the fleet at the Nore. Here the demands of the men, led by a disgraced officer named Parker, were un reasonable. They were repudiated by the men of the western ports and after stern measures the mutiny was suppressed. By October the fleet at the eastern port had so far recovered its morale as to enable Admiral Duncan to defeat the Dutch at the Battle of Camperdown.

The Napoleonic Wars.

An attack upon Santa Cruz failed and in it Nelson lost his right arm. In 1798 Admiral Warren frus trated a French invasion of Ireland and Nelson's overwhelming victory over the French fleet at the Battle of the Nile gave to the British fleet the command of the Mediterranean and Minorca again returned to British hands. In 1799 the Dutch fleet sur rendered and the defence of Acre by Captain Sir Sidney Smith broke Napoleon's dreams of an Eastern empire. Malta was taken by the British fleet in 1800 and in 180 r the formation of the "armed neutrality" of the North was followed by the defeat of the Danes at Copenhagen by Parker and Nelson. Napoleon now threatened to invade England and was closely watched by Nelson in the Channel, and Saumarez and Linois fought with varying results at Algeciras and Gibraltar. France was exhausted and peace being welcome to England, the Treaty of Amiens was signed in March 1802.The peace proved to be but a breathing space and when Napoleon declared war in 1803, the British fleet at once assumed a dominant position at sea. Napoleon's vast preparations for invading England failed through lack of command of the sea. Wherever a French and later a Spanish fleet was in port, a British force waited patiently outside. Cornwallis commanded in the Channel, keeping a close watch upon Brest and Rochefort, Lord Keith guarded the Downs, Sir Robert Calder and Sir John Orde were stationed off Ferrol and Cadiz. In the Mediterranean, Nelson, with only eleven ships of the line, lacking in frigates and with no base to fall back upon, maintained for two years a watch upon Toulon and Cartagena. In these two years many single ship actions were fought the world over, but no clash between the main fleets took place until late in 1805. Then, at last, the French and Spanish fleets put to sea. Evading Nelson in a gale of wind, Villeneuve was chased to the West Indies and back to fight an indecisive action with Calder off Finisterre. The French fleet retired into Cadiz and the combined fleet put to sea in October and met Nelson and its fate off Cape Trafalgar. Once again a British victory at sea removed the terror of a French invasion, and although the war with France lasted for ten more years, the French fleet did not again dare to encounter the British navy.

The Continental System.

Napoleon, despairing of beating Britain at sea, sought to cripple her trade by closing all the ports of Europe to her ships, under the "continental system." England's reply was the bombardment of Copenhagen and capture of the Danish fleet of 7o ships by Admiral Gambier, the occupation of Heligoland in 1807 and the Walcheren Expedition for the relief of Antwerp two years later. Whilst the continental system crip pled British trade in Europe, it turned her attention to the markets of the East and of the West. She secured the strong places of France and Holland throughout the world and Mauritius, Guiana, Ceylon, St. Lucia and the Cape were added to the British Empire. In 1812 the continental system was broken by Russia throwing off the French yoke, but not before the intrigues of Napoleon had caused a war between Great Britain and the United States. This unfortunate war, fought with bitterness and little capacity on both sides, was, at first, not treated seriously by the British Admiralty. In 1812, weak and isolated British ships fell victims to their vigorous opponents, but in the following year the Ameri can ports were blockaded and in 1814 the war was brought to an end by the Treaty of Ghent, a treaty in which no single point of the original quarrel found a mention. After Waterloo, Napoleon fled to Rochefort and there surrendered on board H.M.S. Bellero phon. As he saw the last of the shores of France, he summed up the effect of Britain's sea power in one sentence: "In all my plans. I have always been thwarted by the British fleet." The Nineteenth Century.—The downfall of Napoleon left Great Britain supreme upon the sea, a supremacy unchallenged for a hundred years. During the century her power was used, time and again, to preserve peace, to maintain the freedom of the seas and to suppress slavery and piracy. In 1816 Lord Ex mouth bombarded Algiers and taught the Barbary pirates a les son which led to their extinction. In 182o-23 Lord Cochrane, with a small band of British seamen played a prominent part in the liberation of the South American Republics. In 1827 Codrington, with French and Russian help, fought at Navarino the last battle of the sailing battleships and liberated Greece from Turkish oppression. In 184o Admiral Stopford, at the bombardment of Acre saved the Turkish empire from an Egyptian attack. Twice the British navy intervened to save the Turkish empire from de struction—in 1855 in the Crimea and in 1878 when the victorious Russians advanced upon Constantinople to find the British fleet, under Admiral Phipps Hornby, at anchor in the Golden Horn ready to maintain the passage of the Dardanelles free for the commerce of the world. Besides these there were many minor wars, all directed to the same end—the welfare of mankind. Unobtrusively, British seamen commenced surveying and charting the seas of the whole world and many geographical discoveries were made. In 1848 the hydrographic department of the Ad miralty reported that a great part of the world had been charted and asked permission to complete the work. This obtained, the British naval surveyors in their small ships successfully com pleted the task. The results of their labours were published and are now used by the ships of all nations.

The Admiralty Office.

In 1832 a great reform was intro duced in the administration of the navy by the amalgamation of the navy board and the Admiralty. The dual control of the fleet, which had existed since 1546 was swept away and there came into being the Board of Admiralty (q.v.) and the Admiralty Office. This office has been altered in detail from time to time to meet the changing requirements of the fleet, but British naval admin istration remains, in principle, unaltered since 1832. Many far reaching reforms were introduced in the conditions of service of the seamen and in life on board, one of the most important being the introduction, in 1825, of the system of monthly pay ments to the Lower Deck. The principle of continuous long serv ice, without which no modern fleet can be efficient, has bred for the British Navy a professional personnel, which has become, to no small extent, hereditary both for officers and men. The Naval Academy at Portsmouth, formed in 1729 to train young officers was, in i8o8, renamed the Royal Naval College and a higher standard of education was inaugurated. Fifty years later H.M.S. "Britannia" was attached to the College and in 1863 the "Britan nia" was transferred to Dartmouth, where for forty years young officers were trained in her. In 1903 the educational scheme was brought up to date to meet the scientific requirements of the modern fleet : the "Britannia" was transferred to the new Royal Naval College at Dartmouth and a new system of training en gineer officers for the fleet was started.

The Coming of Steam.

At the close of the Napoleonic Wars the sailing warship had reached its highest stage of development. During the long period of peace following 181 5, battleships became larger and carried more guns, though the guns themselves did not increase in size until after the Crimean War. But during this period the introduction of steam brought about great changes. The steam engine was first tried afloat in 1790 and by 1815 there were nine small steamers working in England. By the navy the new invention was looked upon with disfavour and the Ad miralty in 1816, issued a memorandum stating that "they felt it their bounden duty to discourage to the utmost of their ability the use of steam vessels, as they considered that the introduction of steam was calculated to strike a fatal blow at the naval su premacy of the empire." In the light of after events this is an astounding pronouncement and in the face of it progress was naturally slow. By 1822 the navy possessed one small paddle steamer which was regarded as an expensive and somewhat un pleasant experiment. Five years later three steamships were com missioned as warships and by 184o the number had risen to forty. These were all small paddle steamers and they were used mainly, for towing the great sailing ships in and out of harbour. The chief objection to the adoption of steam in ships of the line was that the paddle wheels interfered with the mounting of the guns on the broadside. This objection was removed by the suc cessful trials with the screw propeller in 1845, and when the Crimean War broke out in 1854, Great Britain possessed a fleet of wooden battleships, fitted with auxiliary steam engines and screw propellers.

Shell and Armour.

In the early part of the 19th century the French and Russians introduced the shell gun, firing an explosive projectile in place of the solid round shot. The British Navy re garded this weapon with suspicion as it was inaccurate and the fuzes were dangerous: it was not until 1837 that, tentatively, it was adopted. The Crimean War proved the value of the explosive projectile and sounded the death knell of the old wooden battle ship. The French were the first to find an antidote by covering the sides of their ships with iron plates and three of these "iron clad" ships proved their invulnerability in action with the Rus sian forts. Profiting by her experience, France, in 1859, built the first armoured ship "La Gloire," a wooden frigate with a belt of iron. Iron merchant ships had been built some years before the Crimean War, but until the value of the explosive projectile was proved, the navy steadfastly refused to countenance them. The success of the explosive shell and the greatly increased power of artillery which followed the invention of the Armstrong gun in 1858, changed these opinions and 186o saw the building of the "Warrior," the first iron warship. She was a ship of 9,000 tons; could steam 14 1 knots and was successful under sail as a full rigged ship. With her 28 seven-inch guns, mounted behind a belt of armour, she was the most powerful fighting ship of her day.

The Transition Period of Naval Architecture.

By 1861 eleven ironclad ships were being built for the navy and the transition period of naval architecture had begun in earnest. Manifold problems faced the constructors, complicated, at first, by the retention of masts and yards. Guns became so large as to require machinery to work them and the old broadside ar rangement gave place to the central battery type, with a few heavy guns mounted in an armoured citadel in the centre of the ship. This method was in turn superseded by the revolving turret con taining one or two heavy guns. The first seagoing turret ships in the British fleet were the "Monarch" and "Captain," carrying four 12-in. guns in pairs in turrets amidships. Both ships were fully rigged and had a large spread of canvas. In 18 7o the "Captain" whilst under sail in the Bay of Biscay, capsized and foundered with the loss of nearly all hands and this disaster brought about the final abolition of masts and yards. In the next decade a number of different types of ship were evolved in the search for the standard modern battleship and, by 188o, the British battle fleet was a collection of samples, no more than two ships being alike. It became recognised that the strength of a modern fleet depended to a great extent upon the similarity of the units composing it and hence the policy of building battle ships and cruisers in classes was instituted. In 188o the "Admiral" class, the first group of battleships built as a class, were laid down. With their heavy guns mounted in pairs at each end and a broadside battery of smaller guns, these ships were the prototype of the battleships of the world for the next twenty five years.

Growth of the Modern Navy.

The Naval Defence Act of 1889 closed the transition period and laid down a settled building policy for the modern navy. The "Royal Sovereign" class, with the "Hawke" and "Intrepid" classes of cruisers, were the first outcome of the act and the battle fleet was gradually built up by the "Majestic," "London," "Duncan" and "King Ed ward VII." classes, which, with their contemporary cruisers, joined the fleet in successive groups, each more powerful than its pred ecessor. The invention of the watertube boiler, followed by the turbine, and the use of oil fuel, revolutionized engineering prac tice and greatly increased the speed and endurance of all classes of ships. The first destroyer, the "Havock," was built in 1893 and was followed by a host of others of ever increasing size and speed. Large armoured cruisers came into being, ships of high speed, moderate protection and heavy armament and 1901 saw the building of the first British submarine. In this department of naval warfare England had been outstripped by France, which had ordered its first submarine as early as 1888. This boat, the "Gym note," was launched in 1888. Naval science made rapid strides in the closing years of the 19th century, especially in naval gunnery and in the use of the torpedo. Early in the 2oth century the German menace, then "a cloud no bigger than a man's hand" was met by the gradual concentration of Great Britain's naval strength in home waters and by increased activity in train ing and practice.

The "Dreadnought" Era.

In 1905 the whole forces of naval science were embodied in the design of one ship, the "Dread nought." Built with rapidity and secrecy, she sailed on her trials exactly a year after her first keel plate was laid. A battleship of 18,000 tons and 21 knots, she mounted ten 12-inch guns in five double turrets. In offensive power, protection and speed she eclipsed any fighting ship that had ever been built and she marked a new epoch in warship construction. The "Dreadnought" was fol lowed by nine other ships with the same armament and in 191 o a new and powerful 13.5 gun passed successfully through its trials. With this gun the "Orion," "King George V." and "Iron Duke" classes were armed and by 1914, twelve of these ships were in commission. Meanwhile the armoured cruiser had developed into a new type of capital ship, the battle cruiser, ships with the armament of a battleship, in which protection was sacrificed to speed. Cruiser duties with the fleet devolved upon yet another new type, the light cruiser, which appeared in 1913. These little ships of 3,00o to 4,00o tons were unprotected, but had great speed and were armed with 6-inch guns.The strength of the British fleet in 1914 is shown in the following table, with, for comparison, the other important fleets of the world at the time.

By the middle of 1914 the British fleet was at the highest state of power and efficiency that it had ever attained in its long his tory. The ships were all that the scientific knowledge of the time could make them, the administration was sound and highly efficient, the dockyards were in first class order and nothing was lacking to equip the fleet. More important still, the long service personnel, officers and men, were incomparable and had been trained in the belief that a great war was coming in their time. The high command at sea was in the hands of a band of great seamen who, when the test came, proved their worth. Under them, in 1914, the British navy calmly faced the uncertainties of the titanic struggle before it, and for its performance therein refer .ence must be made elsewhere (see WORLD WAR, NAVAL).

At the in November 1918, there were more than 1,3 5o vessels flying the white ensign, manned by 407,000 officers and men. Of this great number of ships 42 were battleships and battle cruisers, 786 were cruisers, destroyers, submarines and other small fighting craft and the remainder were trawlers, minesweepers and other auxiliary craft. With the coming of peace retrenchment became inevitable and in the first place, the building programme was rigidly curtailed. At the time there were 211 ships under construction : the building of 86, including 3 battle cruisers, 44 destroyers and 33 submarines was immediately abandoned. A great reduction in personnel resulted from the return to civil life of those who had served through the war in the naval auxiliary forces and by 192o the numbers of officers and men had been re duced to 176,00o and the ships in commission to 332. In 1921 by the Washington Treaty (q.v.) the Great Powers agreed to limit the numbers and size of capital ships and aircraft carriers and to restrict the size of cruisers to i o,000 tons and their guns to 8 inches. Under this Agreement, Great Britain sent no fewer than 20 modern capital ships to the shipbreakers' yards and there followed a reduction in the permanent personnel. A drastic scheme of retirement of officers and of elimination amongst the older men of the lower deck brought the total personnel down to 107,800 in 1923 and to 99,00o by the end of 1924. Since then the numbers have risen gradually to a peace complement of 103,000 officers and men.

The armistice did not immediately bring the warlike activities of the navy to an end. The minefields around the coast had to be swept clear and this hazardous task was accomplished, in the half year following the armistice, by a flotilla of over 700 vessels manned, chiefly, by British fishermen. Until the end of 192o the navy was engaged in the Baltic, the White Sea and in the Black Sea in supporting the unsuccessful opponents of Bolshevik Russia. In 1922, the presence of a strong British fleet at Constantinople facilitated the prolonged peace negotiations with Turkey and in other parts of Europe the presence of British warships had a pacifying and stabilizing effect.

Redistribution of the Fleet.

The post war redistribution of the British fleet thus occupied a period of over three years. The Grand fleet was officially disbanded in April 1919 and its place was taken by an Atlantic fleet of nine battleships and five battle cruisers whilst a second fleet in home waters, the Home fleet of six battleships was formed. At the same time a squadron of six battleships, with cruisers, destroyers and submarines, was sent to the Mediterranean station. Owing to the pressing needs of economy, the Home fleet was abolished at the end of 1919, and the ships that were not placed in reserve were merged into the Atlantic fleet. Until the end of 1922 the bulk of the British fleet was thus kept in home waters where the squadrons were large enough to solve the many post war problems of gunnery concentra tion, fleet torpedo tactics, destroyer attacks, anti-submarine and anti-aerial tactics. In the years following 1922 unrest in the Near East and the general strategic situation led to a gradual strengthening of the British fleet in the Mediterranean, and by 1926 the bulk of the fleet was stationed in those waters. Based upon Malta, the Mediterranean fleet is placed astride the great trade routes to the Far East and composed of units in constant commission it is well situated for the general defence of the empire.Meanwhile seven cruiser squadrons have been formed for service in different parts of the world. One squadron is attached to the Atlantic fleet, two to the Mediterranean ; one is stationed at the Cape, one in the West Indies, one in the East Indies and one in China, where there are also two flotillas of river gunboats for duty on the Yangtse and Canton rivers and destroyer and sub marine flotillas. This organization permits of early reinforcement in any part of the world, as was demonstrated in 1927, when trouble broke out in China, and a cruiser squadron, a destroyer flotilla and an aircraft carrier were sent from the Mediterranean to strengthen the China Squadron. Upon each foreign station a number of small sloops are maintained to supplement the work of the cruisers in policing the trade routes and visiting the out lying parts of the empire.

After the armistice until the end of 1922, the construction of British warships practically ceased, work being confined to the leisurely completion of vessels that were too far advanced to be abandoned. No new ships were laid down, though the building of four improved "Hood's" was contemplated in 1921. These four ships were abandoned as the result of the Washington Treaty which left Great Britain with only one ship of post-Jutland design. The United States had three and Japan two, and in order to equalise the quota in this type, Great Britain laid down the two battleships "Nelson" and "Rodney" in 1922. These two ships, which conform to the agreed limitations of the Treaty, joined the fleet at the end of 1927 and the four "King George V." class battleships were broken up in their stead.

Need of Cruisers.

In 1924 the cruiser situation in the British fleet became acute. With the exception of the four ships of the "Hawkins" class the average size of the cruisers of the fleet was under 5,00o tons. These ships had been built during the war as "Light Cruisers" for service with the fleet in the Narrow Seas and they were not designed for service upon foreign stations. Moreover, most of these ships had seen strenuous war service which had shortened their lives. Their replacement by a more suitable type was necessary and a programme was started to build twelve ships of io,000 tons and six of 8,000 tons: the Australian Government at the same time laying down two io,000 ton ships. By the Washington Treaty the size of cruisers had been limited to io,000 tons and their guns to 8 inch. This maximum became a minimum and all the principal naval powers, in laying down new cruisers, built some up to the io,000 ton limit. Although in British opinion these ships were too large and expensive for the work they were required to do, Great Britain, mindful of the empire's 8o,000 miles of vital trade routes, was forced to build ships which were powerful enough to deal with any rival they might meet. At the Geneva conference in 1927, Great Britain made sweeping proposals for economy by further limiting the tonnage and the size of the guns of capital ships and also suggested that the per missible tonnage of cruisers should be reduced and that they should be restricted from carrying any gun greater than six inch. The conference failed to agree upon this latter point and was adjourned: in spite of the failure to agree to a limitation in the size of cruisers, Great Britain in 1928 curtailed her cruiser programme by cancelling the laying down of two io,000 ton ships and by proceeding only with the construction of the 8,000 ton class. Turning to destroyers, some sixty of these vessels that were well advanced at the armistice, were completed and no new ones were begun until 1925. Two experimental destroyers were then laid down : they joined the fleet in 1927 and as the result of their extended trials, a new class of these vessels was started to replace the older boats as they became worn out.After the war Great Britain twice expressed her willingness to abolish the submarine as a naval weapon of war. Other nations could not agree to this, but for six years after the armistice, British submarine construction was confined to the completion of vessels already in hand and to experimental work. Only one submarine was completed in this period, the large ocean going submarine "XI." In 1925, with the laying down of the new "0" class, a submarine replacement programme was put in hand.

Post-War Administration.

No radical change in the ad ministration of the navy or of the dockyards was brought about by the World War, with the exception of the formation of the naval staff. On the outbreak of hostilities the navy had a very inadequate staff organization; war experience demonstrated its necessity and there is now a scientifically trained and efficient naval staff at the service of the fleet. New material, new methods and the advances of science have led to specialized training in some directions, notably in electrical matters, but, in principle, the general organization of the navy has remained unaltered since 1914. The war produced no startling innovations in naval weapons. The heavy gun maintains its pride of place as the chief weapon; the torpedo has increased in power and range but not in accuracy; the possibilities and also the limitations of the submarine were demonstrated : countermeasures against mines were discovered and the rapid development of the aeroplane, alone, has introduced a new factor into naval tactics. Since the war the Fleet Air Arm has been formed, under the dual control of the Admiralty and the Air Ministry. The aircraft carriers are naval ships and 7o% of the flying personnel are naval officers and men. The remainder of the personnel and all the flying material are supplied by the air force, who are also responsible for flying training. The cost of the Fleet Air Arm is borne on the Naval Estimates.

In

1928 there were maintained in commission just over 300 ships. Of these more than 1 oo were vessels attached to training establishments, surveying vessels and other auxiliary units. The strength of the navy of the British Empire in 1928 is shown in the following table, in comparison with that of the principal naval powers. The number of the ships shown as "projected" in the table was to be subject to alteration after the revision of the Washington Treaty in 1931.The British Army and Navy at the beginning of the World War in Aug. 1914 had separate administrative organizations for their air services which were the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Air Service respectively. These were amalgamated early in 1918 and the Air Ministry was formed. It is a state depart ment and the Secretary of State for Air is the responsible Cabinet Minister. He is also president of the Air Council, whose functions are analogous to those of the Board of Admiralty and the War Council.

The Air Council.

In addition to the president, the Air Coun cil is composed of the under Secretary of State for Air, who must be a member of Parliament (either House), four service mem bers (the chief of the air staff, the air member for personnel, the air member for supply and research and the deputy chief of the air staff) and the secretary, a civil servant. The air ministry pro vides the administrative machinery for giving effect to the Air Council's decisions and it consists of various main departments. The directorate of civil aviation deals with all matters connected with the regulation of civil flying. It comprises an accident branch, which investigates the causes of accidents, whether to service or to civil aircraft ; an air transport branch, and a licensing branch. The department of the secretary is charged with the internal ad ministration of the ministry and is responsible for the general routine. Included in the department are the directorates of accounts, contracts and lands and the meteorological office.The department of the chief of the air staff includes the directorate of operations and intelligence and the directorate of staff duties and organization, which, in addition to the functions implied by its designation, controls the signalling branch. This branch deals with questions of wireless communication for both the Royal Air Force and civil aviation. The directorate of works and buildings is also under the chief of the air staff. The depart ment of the air member for personnel deals with the recruitment, discipline, general welfare and training of officers and other ranks of the Royal Air Force. The directorate of medical services forms part of this department.

The department of the air member for supply and research includes the following directorates: (I) the directorate of scien tific research and technical development, divided into branches which deal respectively with design, armament, instruments and scientific research; (2) the directorate of airship development ; (3) the directorate of aeronautical inspection, which is responsible for the inspection of all materials used in the construction of air craft and engines; (4) the directorate of equipment, which is responsible for the supply, storage and issue of all equipment for the Royal Air Force.

The Royal Air Force.

The officers of the general duties or military branch of the Royal Air Force are divided into two cate gories. About 5o% of the total are those for whom the Air Force provides a permanent career. Practically all officers in this cate gory must pass through the R.A.F. Cadet College at Cranwell. The remainder consists of officers serving temporarily in the Royal Air Force; either those from civil life who engage for five years on the active list followed by a period in the reserve, or those naval officers who, by agreement with the Admiralty, pro vide personnel for the Fleet Air Arm for certain periods. The other ranks are filled either by boys who go through an apprentice ship in a trade at one of the boys' training establishments, passing into the ranks on reaching the age of 18, or by men enlisted direct from civil life. The normal period of service is seven years with the Colours and five with the reserve. In addition to the general duties branch of the Royal Air Force, there are the stores, account ing, medical, dental, and chaplain's branches.Units are divided into the following types :— The present organization of the Royal Air Force, full details of which appear in the Royal Air Force Monthly List is comprised of the following commands : Home. 1. The air defence of Great Britain which comprises all units and formations of the home defence force organized under three subordinate commands, viz., Wessex bombing area (regular bombing squadrons), fighting area (fighter squadrons), and No. r air defence group (cadre and auxiliary squadrons) .

2. The inland area which comprises all units in Great Britain with the exception of those units included in the air defence of Great Britain, the coastal area and the Cranwell and Halton Commands.

3. The coastal area which comprises all units serving at the following stations :—Calshot, Lee-on-Solent, Gosport, Cattewater, Donibristle, Leuchars and Felixstowe; headquarter units in air craft carriers in home waters ; flights embarked in such carriers; and all recruiting depots.

4. Royal Air Force Cranwell which comprises the cadet college and all units at Cranwell.

5. Royal Air Force Halton which comprises No. r School of technical training and all units at Halton.

Overseas. I. Royal Air Force Middle East which comprises all units in Egypt and the Sudan.

2. Royal Air Force Transjordan and Palestine which com prises all units in those countries.

3. Royal Air Force `Iraq comprising all units in `Iraq.

4. Royal Air Force India comprising all Air Force units in India.

5. Royal Air Force Mediterranean comprising units in Malta.

6. Royal Air Force Aden comprising units in Aden.

7. Royal Air Force China comprising units at Hongkong and embarked in Aircraft carriers.

In addition to the above commands there exist the following Establishments controlled by the Air Ministry : r I. The Royal Aircraft Establishment, South Farnborough.

2. The Royal Airship Works, Cardington.

3. The Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment, Felix stowe.

4. The Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment, Martlesham.

The approximate strength of the Royal Air Force in 1928 was: officers 3,45o; other ranks 28,500. (X.) British Finance After 1793.—The revolutionary and Napole onic Wars imposed such a strain on English finances as to throw all previous wars into the shade. The total cost is estimated to have exceeded £800,o00,000. War expenditure began gradually. By 1795 it had reached about L20,000,000 a year. At first no taxation worth mentioning was imposed; all was borrowed. In 1797 the restriction of cash payments by the Bank of England marked a new stage. By a great effort tax revenue was raised from L19,000,000 in 1796 to f32,500,000 in A notable novelty was the income tax. As imposed by Pitt in 1798, this tax (at the rate of 2/– in the pound) was based on personal declarations of income by the taxpayers. It was im possible to secure full and honest declarations or to check evasion, and the yield of about £5,500,00o a year was disappointing. The peace secured by the Treaty of Amiens in 1802, transitory though it turned out to be, was accompanied by the repeal of the income tax. On the other hand additional customs and excise duties were imposed and in 1803, when the war broke out again, the tax revenue reached £40,000,000.

Addington, who was then prime minister and chancellor of the exchequer, reimposed the income tax, but with an important and indeed epoch-making change. He established the system of tax ation at source. Incomes were to be declared so far as possible by those who paid them (such as the tenant of land or the borrower on mortgage) instead of by those who received them, and the tax collected accordingly. This proved to be the solution both of the problem of war taxation at the time, and of the prob lem of income taxation in the future. The rate of income tax, at first 1/– in the pound, was raised in 1807 to 2/–, and the tax at that rate regularly yielded from £ 12,000,000 to £ 14,000,000 a year.

The yield of taxation was swollen all round by an inflated paper currency and a high price level, and in the years 1813 to 1815 an average annual revenue of £79,000,000 was provided towards an average expenditure of £104,000,000. Customs and excise yielded an average of £44,000,000 and income tax £14,500,000. Indirect taxes had been constantly added to, and eventually at tained a degree of complexity and vexatiousness which has become notorious (and immortalised by Sidney Smith's witty description).

Though tax revenues had been thus drastically extended in the latter part of the war, the deficits still necessitated very heavy borrowing. The practice was followed of issuing stock far below par; 5% and 4% stocks were issued, it is true, as well as 3 per cents, but the 3 per cents predominated and were being plentifully issued even at times when 5 per cents could not be sold at par. In the whole period 1793-1816 the funded debt was increased by £566,600,00o net (stock redeemed out of the sinking fund and held by the National Debt commissioners being deducted). The net proceeds in money were only f368,600,000. The floating debt (which had been f 10,000,00o in 1792) had risen to £5o,000,000 In 1814 it had been £60,000,000.

Added to the pre-existing debt this made a total of f846,000,000, and the annual charge for interest was some L32,000,000, including terminable annuities amounting to £1,898,000, which were not represented in the capital of the debt. The difficulty of meeting this burden was increased when the Government was deprived by an adverse vote of the House of Commons in 1816 of the income tax. The years following the peace were a period of falling prices and depression. Rigorous economy (with which the name of Joseph Hume is associated as an indefatigable critic of Govern ment extravagance) brought down expenditure below f60,000,000 a year, and by 1834 even below £50,000,000. Yet the oppressive and vexatious system of indirect taxation had to be continued to make ends meet.

Some relief was soon obtained from the conversion of the debt. The Government had the right to repay the 5 per cents and the 4 per cents at par. In 1821 this option enabled them to convert the 5 per cents to 4 per cents (with an increase of 5 per cent in nominal capital). The stock converted amounted to L150,000,000 and the saving in interest was £1,200,000 a year. Two further conversions (1824 and 1830) reduced the 4 per cents to 31- and saved a further f r,000,000 a year. In 1844 the 31 per cents were in turn converted to a new stock bearing 3-1- per cent for ten years, and thereafter 3 per cent. Thus the funded debt had been reduced to a uniform 3 per cent. But the relief thus gainNI was restricted to the stocks which had originally yielded more than 3 per cent. The burden of the 3 per cents which had amounted in 1815 to £547,000,000 could be diminished in no other way than by the operation of the sinking fund, till the yield of gilt-edged securities at market prices fell below 3 per cent.

The sinking fund instituted by Pitt had become an absurdity; an enormous sum had to be applied every year to the redemption of debt, even when the requisite revenue was not forthcoming. Money was even raised by the creation of floating debt to redeem funded stock. After tentative amendments this ambitious but unpractical plan was swept away in 1829 in favour of a simple provision requiring the actual excess of revenue over expenditure in any year to be applied to the reduction of debt. This provision remains and is called the "old sinking fund." For zo years after 1815 there were as a rule moderate surpluses. In 1836 and 1837 heavy borrowing became necessary to provide £20,000,000 of compensation to the proprietors of slaves emanci pated in the West Indies.

It was a time of bad trade, and in the years that followed there were serious deficits, aggravated in 184o by the adoption of the penny post, which involved a loss of revenue of £i,000,000 a year. Financial difficulties were a contributory cause of the dis credit and fall of Lord Melbourne's Government in 1841.

The Coming of Free Trade.

The budget fell into the master ful hands of Sir Robert Peel, who as prime minister and first lord of the Treasury quite over-shadowed Goulburn, the chancellor of the exchequer.The path to solvency was found in the revival of the income tax. At a rate of 7d. in the pound it yielded £5,000,00o a year. The deficit in 1841 had been £2,1oo,000, and the new tax provided a margin to admit of important reforms. It was the age of the classical economists and their championship of free trade. A beginning had been made with the mitigation of protective customs duties in 1825 by Robinson and Huskisson. Peel in his budget of 1842 made an important further advance. He repealed numerous vexatious duties which yielded comparatively little revenue, but which hampered trade. A further instalment of similar reforms came in 1845. The repeal of the corn laws in 1846 can hardly be regarded as a fiscal measure ; the slight loss of revenue counted for little in comparison with the major issues raised.

The traditions of Peel were carried on by the so-called Peelite party, the section of Conservative Free Traders who played a conspicuous part in politics till 1859, and thereafter contributed to create the modern Liberal Party. Peel's successor in finance was Gladstone, the outstanding figure in that sphere in the i9th century.

In the field of taxation development was in the direction of free trade. Customs duties came to be confined to products which either, like tea or tobacco, were not produced at all in this country, or, like beer and spirits, could be subjected to excise duties ap proximately equal to the customs duties, which eliminated all protective effect. The simplification of indirect taxation begun by Peel was carried out to the limit, and the number of corn modities taxed reduced to a minimum. From the repeal of the sugar duties in 1874 till their reimposition in 19oi the only com modities taxed were alcoholic liquors, tea, coffee, cocoa, tobacco and dried fruits.

The income tax had been intended by Peel to be a temporary expedient, and this was not forgotten. For long it was out of the question to dispense with it. But in 1874 Gladstone, finding it possible to reduce the rate to 2d. in the pound in the forthcoming budget, seriously proposed to repeal the tax altogether. His Government fell, and soon it became necessary to increase the tax. The prospect of repeal vanished and has never revived.

On the side of expenditure the tradition of severe economy begun in the period after 1815 was continued almost to the end of the i9th century. The instrument used for this purpose was the Treasury. The sanction of the Treasury is required to be given, in considerable detail, for the expenditure of all the other departments. Thereby the chancellor of the exchequer is enabled to impose any desired standard of economy upon them.

Progress with debt redemption was slow. In 1853, on the eve of the Crimean War, the debt amounted to £769,000,000, and the war (costing £69,000,00o in all) added £39,000,00o to this total. Apart from the rather fortuitous surpluses of revenue over ex penditure, there was no systematic sinking fund. Gladstone in 1863 started a new system of "terminable annuities" for the pur pose of redeeming debt. A sum of £5,000,000 3 per cents, in which savings bank deposits were invested, was cancelled, and in place of the interest the exchequer was made liable to pay an annuity for 22 years including instalments of capital sufficient to accumulate during that period to the equivalent of the stock cancelled. The system was further developed, and in 1875 the annuities amounted to £3,500,000.

New Sinking Fund 1875.

The creation of a systematic sink ing fund was the work not of Gladstone, but of the Conservative chancellor of the exchequer, Sir Stafford Northcote. He obtained an act in 1875 which set up a fixed debt charge of £28,000,00o a year, a sum more than sufficient to cover interest and terminable annuities, and providing a margin to be applied to debt redemption (the "new sinking fund"). So long as the fixed amount was not tampered with, the margin available for redemption would grow as the charge for interest diminished. The provision requiring the surplus revenue to be applied to the redemption of debt (the "old sinking fund"-) still remained in operation.It is the practice to legislate every year on the subject of revenue and debt (the annual Finance Act), and surpluses or portions of them have often been diverted by a special clause from the redemption of debt to expenditure more or less of a capital nature. The fixed debt charge was reduced to £26,000,000 in 1887, to £25,000,000 in 1890 and to £23,0oo,000 in 1899.

The last quarter of the i9th century was a period of exception ally low rates of interest, and the 3 per cents which had consti tuted the greater part of the National Debt since 1844 rose to par, and would have risen higher but for the Government's right to repay them at par. In 1888 the chancellor of the exchequer, Goschen, carried through a conversion scheme, £514,aoo,000 of 3 per cents being converted to a new stock (new Consols) which yielded z a per cent for 15 years and thereafter 21.

A turning point in financial policy was marked by the retirement of Gladstone in 1894. Though he was 84, his resignation was not entirely without political significance; the occasion for it was the insistence of his cabinet upon a costly naval programme. Ex penditure began to mount rapidly. Soon the Boer War 1902, costing £ z 23,000,000) added £ 159,000,00o to the debt (yielding £ 15 z,000,000 of cash) .

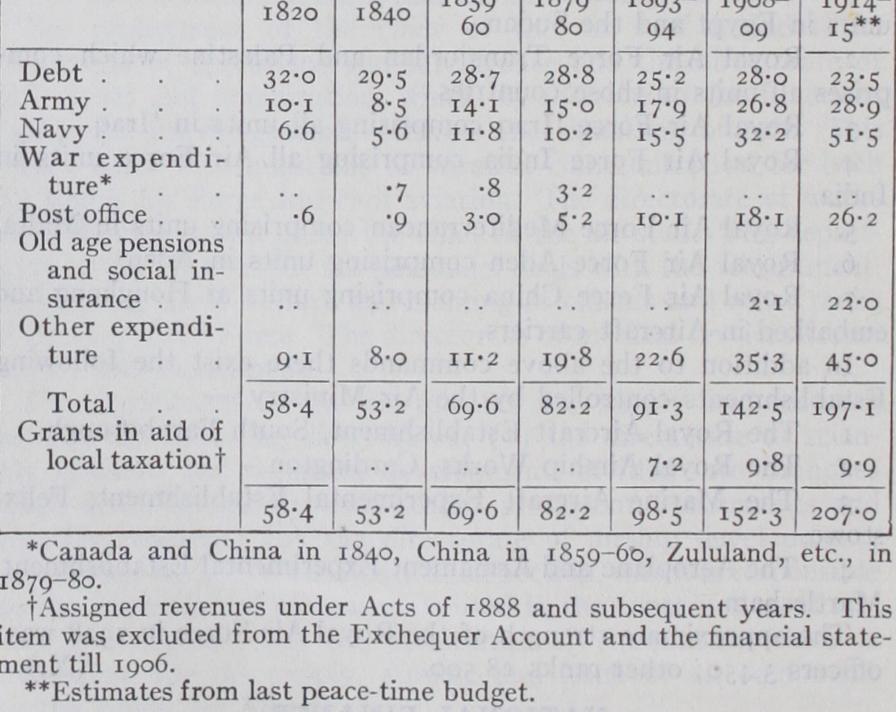

The growth of British expenditure is illustrated by the following table (in £ millions) : This increase in expenditure meant large increases in taxation. An important new departure was made at the outset by Sir Wil liam Harcourt, chancellor of the exchequer in the Liberal Gov ernment from which Gladstone retired in 1894. This was the application to the death duties of the principle of graduation according to the total value of the estate left by a deceased per son. A small estate paid 1 % or 2%, one of f i,000 to Li o,000 paid 3%, while at the top of the scale one above £i,000,000 paid 8 per cent.

With expanding trade and revenue no further taxation was re quired till the Boer War. Towards the cost of the war a sum of £71,000,00o was raised by taxation. Income tax and indirect taxes were increased and new taxes were imposed, an export duty on coal (1901), and import duties on sugar (1901) and wheat (1902).

The coal duty and wheat duty were repealed again in 1903. The wheat duty was noteworthy as being the first protective duty imposed since the days of Peel, and its repeal was due to the controversies which it threatened. Immediately upon it there followed Joseph Chamberlain's campaign in favour of colonial preference (see PROTECTION) .

In the early years of the Liberal Government which took office in Dec. 1905, good trade facilitated remissions of taxation and big repayments of debt. The debt charge had been raised by Austen Chamberlain to £28,000,00o and was temporarily further in creased. Income tax remained at i/– in the pound (as compared with 8d. just before the Boer War) but H. H. Asquith introduced a system of differentiation in favour of earned incomes below f 2,000 a year, which paid 9d. only.

In 1908, coincidently with a trade depression which reduced the productivity of the revenue, came new demands on the Exchequer. Asquith's Old Age Pensions Act of that year was soon followed by D. Lloyd George's projects for Health Insurance and Unemployment Insurance. The cost of the navy was still growing. In the budget of 1909 an enormous estimated deficit had to be provided for by heavy new taxes.

That budget became the occasion of a great constitutional crisis. The most contentious proposals were those for the taxation in various forms of "land values," especially the "unearned in crement" of economic rent. Heavy increases in public house license duties also evoked opposition. The graduation of the estate duties was made more severe. The duties on spirits and tobacco were raised. But the feature of greatest permanent im portance was the institution of a supertax, or additional income tax, on large incomes.

Incomes above £5,000 were taxed at 6d. in the pound on the excess over £3,000. At the same time the rate of income tax on unearned income was increased from is./– to Is./2d.

After a prolonged and stormy passage through the House of Commons the Finance Bill was rejected by the House of Lords. Since the 17th century it had been a constitutional convention that the House of Lords could not amend a money bill. But it could not be prevented from rejecting one. In 186o the House of Lords rejected a bill repealing the paper duties, and the Gov ernment (in which Gladstone was chancellor of the exchequer) retorted by putting all the budget proposals in a single Finance Bill. Since then it had been assumed that the rejection of the Finance Bill as a whole would never be practical politics, and that the power of the House of Lords over details of the budget had dropped into abeyance.

Parliament Act, 1911.

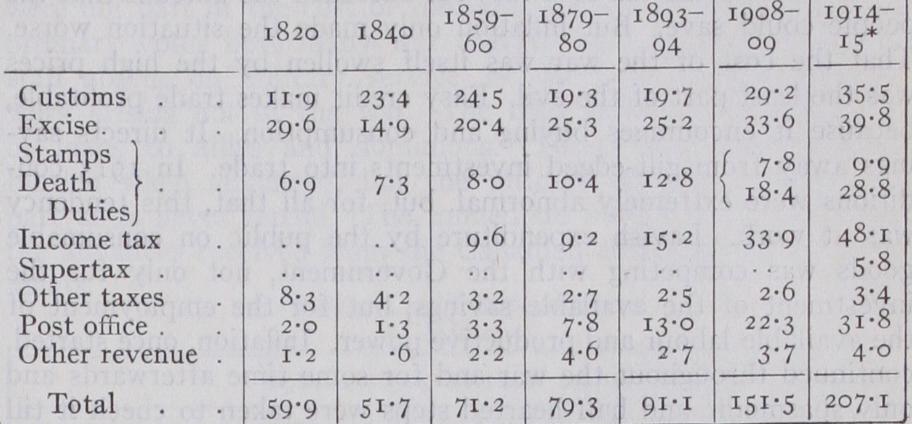

In 1909 the question was suddenly revived. Two successive general elections in 1910 were required to enable the Government to pass the budget (April 191o) and the Parliament Act, 1911, which limited the powers of the Lords and almost destroyed their power over finance. After the great effort of 1909 the natural expansion of revenue sufficed to cover expenditure till 1914. In that year further taxation became nec essary, and the budget as finally adopted (before the war crisis) provided for an increase in estate duties, a rise in the income tax on unearned incomes from is. 2d. to Is. 3d. (the earned still remaining at 9d.), and an important extension of the supertax. Supertax was applied to all incomes over £3,000, and was more elaborately graduated (the rate on the excess of an income over f 8,000 was is. 4d. in the pound) . The estimated yield for a full year was thereby raised from f3,3oo,00o to £7,770,000 (see IN COME TAX).The following table shows the growth of taxation in the century preceding the Great War (in £ millions) : *Estimates from last peace-time budget.

The War Period.

From the beginning of the World War in Aug. 1914 it became impossible to dissociate the budget position from the state of credit generally. In the first place, the Govern ment had to come to the assistance of the financial world and support credit through the initial crisis. Secondly, expenditure on the war soon grew to such dimensions as to put an almost unbearable strain on the financial fabric of the country.The outbreak of the war threw first the stock exchanges and then the foreign bill markets of the world, but above all of Lon don, into utter disorder. The machinery of remittance to Lon don broke down almost completely and the London accepting houses found themselves faced with bankruptcy. The Govern ment was forced to step in and to proclaim a moratorium for debts, statutory power was taken for the Treasury to issue legal tender currency notes for f 1 and los. and the Government guar anteed advances by the Bank of England to acceptors to pay off pre-moratorium bills (see STOCK EXCHANGE).

It was in the midst of this state of confusion that the early stages of the war were financed. For the initial expenses, ad vances of £14,720,00o were obtained from the Bank of England on "ways and means" (i.e., under the powers annually conferred by the Consolidated Fund Act and Appropriation Act) . The war was costing about £I,000,000 a day. There followed half-a-dozen issues of Treasury bills of £ 15,000,00o at a time. In Nov. 1914 additional taxation was imposed and a loan of £350,000,000 (32% at 95, redeemable 1925-28) was decided on. By that time serious unsoundness was already developing in the situation. The issue of f 90,000,000 of Treasury bills did not in itself overstrain the market. But the advances made by the Bank of England for the pre-moratorium bills, with its advances to the Government and large imports of gold, destroyed the bank's power of controlling the money market. Bank rate had been reduced to 5% on the reopening of the banks on Aug. 7, but in Sept. it ceased to be effective and the market rate fell to 3%. In Nov. it fell below 3. Part of the 3% loan was taken by the banks, and in any case the loan was not applied to strengthen the position of the Bank of England. In Feb. 1915 the market rate of discount fell below 2%. The private deposits at the Bank of England exceeded L 130,000,000.

Growth of Inflation.--At