Hallstatt

HALLSTATT. The first iron age of Central and Western Europe and the Balkans is known as the Hallstatt period after the place of that name in Upper Austria. It is not the cradle of the earliest iron age culture, but the site where objects char acteristic of it were first identified. Here, between 1846-99, wards of 2,000 graves were found. The majority fall into two groups, an earlier (c. 900-70o B.c.) and a later (c. 700-40o B.c.). Hallstatt became an important settlement in the first iron age. Both cremation and inhumation were practised, the latter slightly preponderating. The cremation graves are on the whole the richer and, viewed in the mass, contain older objects than the inhumation burials, but this should not be pressed too strictly, for the two rites overlapped chronologically. Most of the types of grave furniture are found elsewhere in phase C and D burials (see below), but objects of a peculiar character occur as well. The pottery unearthed by the earlier excavators was practically all destroyed. Near by lies the prehistoric salt mine where salt was extensively obtained. A number of shafts were sunk, often to a considerable depth, sometimes at a steep angle. Thanks to the preservative nature of the salt, their implements, parts of their clothing and even (at Hallein as well as at Hallstatt) the bodies of the miners themselves have come to light.

Typology and Art.—Reinecke divides the Hallstatt period into four phases, A, B, C, D (see IRON AGE). He equates the first of these with the period of the Urn-field culture. Schumacher regards the latter as comprising the last phase of the bronze and the first of the iron ages. Others hold that Hallstatt A and B are in reality the latest bronze age, and that the iron age did not begin until Hallstatt C. Others regard it as the last period of the bronze age. The fourfold division is adhered to in the following account.

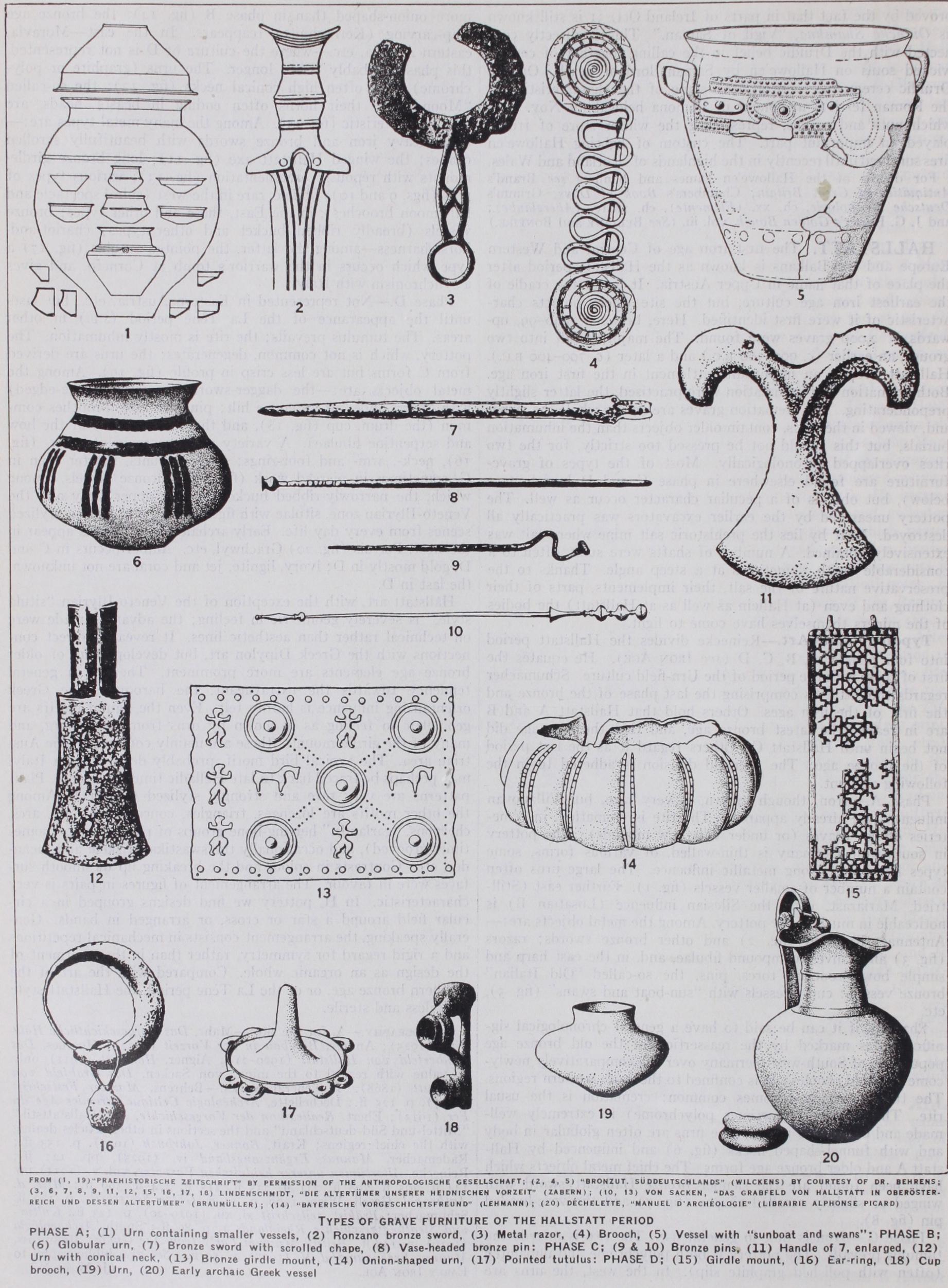

Phase A.—Iron, though known, is very rare, but Villanovan influences are already apparent. The rite is cremation, in ceme teries of flat graves (or under very low mounds). The pottery in south-west Germany is thin-walled, of various forms, some types betraying strong metallic influence. The large urns often contain a number of smaller vessels (fig. 1). Further east (Still fried, Mariarast, etc.) the Silesian influence (Lusatian B) is noticeable in much of the pottery. Among the metal objects are : Antennae, Ronzano (fig. 2) and other bronze swords; razors (fig. 3) and knives, compound fibulae, and, in the east harp and simple bow brooches, torcs, pins, the so-called "Old Italian" bronze vessels : cups, vessels with "sun-boat and swans" (fig. 5), etc.

Phase B, if it can be said to have a general chronological sig nificance, is marked by the reassertion of the old bronze age population of South-west Germany over the comparatively newly come Urnfield peoples. It is confined to the more western regions. The tumulus again becomes common ; cremation is the usual rite. The pottery (sometimes polychrome) is extremely well made and of various forms. The urns are often globular in body and with funnel-shaped necks (fig. 6) and influenced by Hall statt A and older bronze age forms. The chief metal objects which have been found are the slender bronze Hallstatt sword with winged or slightly scrolled chapes (fig. 7) and the vase-headed pin (fig. 8) .

Phase C.—Iron is first in general use. The rite is mixed; the tumulus prevails. The pottery is both polychrome and unpainted (often with polished graphite slip). In the west, the urns are more onion-shaped than in phase B (fig. 14) ; the bronze age chip-carving (Kerbschnitt) reappears. In the east—Moravia, eastern Austria, etc.—where the culture of D is not represented, this phase probably lasted longer. The urns (graphite or poly chrome) have often high conical necks (fig. 12) ; the so-called "Moon-idols," their horns often ending in beasts' heads, are very characteristic (fig. 13). Among the many metal types are : long, heavy iron and bronze swords with beautifully scrolled chapes; the winged Hallstatt axe (fig. I I) ; long bronze girdle , mounts with repousse ornamentation (fig. 13) ; various types of pins (figs. 9 and Io) ; fibulae, rare in the west (spiral spectacle and half-moon brooches), in the East, these and other types; bronze vessels (broadly ribbed bucket and other types ; chariot-and horse-harness—among the latter, the pointed tutulus (fig. 17) a type which occurs in the warrior's tomb at Corneto, and gives a synchronism with Italy.

Phase D.—Not represented in Eastern Austria, etc., but lasts until the appearance of the La Tene period (s.v.) in other areas. The tumulus prevails; the rite is mostly inhumation. The pottery, which is not common, degenerates ; the urns are derived from C forms but are less crisp in profile (fig. 19). Among the metal objects are :—the dagger-sword (sometimes one-edged) with "horse-shoe" or antennae hilt ; pins are rare, brooches com mon (the drum, cup (fig. 18), and the later variants of the bow and serpentine fibulae). A variety of ring ornaments : ear- (fig. 16), neck-, arm- and foot-rings; girdle mounts, shorter than in C, sometimes in pierced work (fig. 15). Bronze vessels, among which, the narrowly-ribbed bucket, and in upper Italy and the Veneto-Illyrian zone, situlae with figured motifs in friezes, stylized scenes from every day life. Early archaic Greek vessels appear in the west, Pertuis (fig. 2o) Grachwyl, etc. Amber occurs in C and D, gold mostly in D; ivory, lignite, jet and coral are not unknown, the last in D.

Hallstatt art, with the exception of the Veneto-Illyrian "situla style," is severely geometric in feeling; the advances made were on technical rather than aesthetic lines. It reveals indirect con nections with the Greek Dipylon art, but developments of older bronze age elements are more prominent. There is a general tendency towards the extravagant, the baroque. The Greek orientalizing influence is hardly felt. Even the figural motifs are geometric in feeling as is shown by urns from Oedenburg, and many of the girdle-mounts; these are mainly confined to the Aus trian area. The typical bird motif, probably derived from Italy, may perhaps be traced back to late Helladic times in Greece. Plant patterns are very rare and strongly stylized (Urmitz). Among the other motifs are lozenges, triangles, concentric circles, arcs, chevrons, "garlands," herring-bone groups of parallel lines (some times grooved), and occasionally the swastika, triskele and mean der, etc. Contrasts in colour and the breaking up of smooth sur faces were in favour. The arrangement of figures in pairs is very characteristic. In pottery we find designs grouped in a cir cular field around a star or cross, or arranged in bands. Gen erally speaking, the arrangement consists in mechanical repetitions and a rigid regard for symmetry, rather than in the treatment of the design as an organic whole. Compared with the art of the northern bronze age, or of the La Tene period, the Hallstatt style is lifeless and sterile.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-A,

for the site:—Mahr, Das Vorgeschichtliche HallBibliography.-A, for the site:—Mahr, Das Vorgeschichtliche Hall- statt (1925) ; Andree, Bergbau in der Vorzeit (1 92 2) ; Hoernes, Das Gruberf eld von Hallstatt (192o-21) ; Aigner, Hallstatt (191 I) only of value with regard to the mine ; von Sacken, Das Grab f eld von Hallstatt (1868). B, general works:—Behrens, Mainzer Festschrift (1927), p. 125 ff.; Dechellette, Archeologie Celtique, Premier Age du Fer (1913) ; Ebert, Reallexikon der Vorgeschichte, see "Hallstattstil," "Mittel-und Siid-deutschland" and the sections in other articles dealing with the chief regions; Kraft, Bonner, Jahrbuch (1927), p. 153 ff.; Rademacher, Mannus Ergiinzsangsband iv. (1925) , pp. 127 ff.; Reinecke, Altertiimen unserer heidnischen V orvater, vol. v. (1911) pp. 144 ff. 205 ff. 208 ff. 231 ff. 235 ff. 315 ff. 324 ff. 399 ff.; Mitt. d. Anthropol. Gesell. Wien. 1900, p. 44 ff. Gotze Festschrift, p. 122 ff. Schumacher: Prahist. zeitschri f t xi. xii. (1919-20) , p. 123 ff., Kultur und Siedlungsgeschichte Rheinlands 1, p. 86 ff.; Smith, Archaeologia (1916), p. 145 ff., British Museum Early Iron Age Guide; Stampfuss, Mannus Ergiinzungsbd. V. (1927), p. 5o ff. See also bibliography to j EARLY IRON AGE. (J. M. DE N.)