Halo

HALO, in physical science a luminous circle, with various auxiliary features, surrounding the sun or moon. The word is derived from the Greek &Xcws, a threshing-floor and used to denote the disc of the sun or moon, probably on account of the circular path traced out by the oxen threshing the corn. It was later used for any luminous ring, such as that encircling the sun or moon, or portrayed about the heads of saints.

A halo is caused by the ice-crystals in the atmosphere producing reflection and refraction of the light. The optical phenomena pro duced by atmospheric water and ice may be classified according to the relative positions of the luminous ring and the source of light. Halos and coronae, or "glories," encircle the luminary; rainbows, fog-bows, mist-halos, anthelia and mountain-spectres have their centres at the anti-solar point. Halos are at definite distances (22° and 46°) from the centre of illumination, and when coloured have red on the inside, being caused by refraction; coronae surround the sun at variable distances but always nearer than 22° and the red colour appears on the outside—the result o: diffraction.

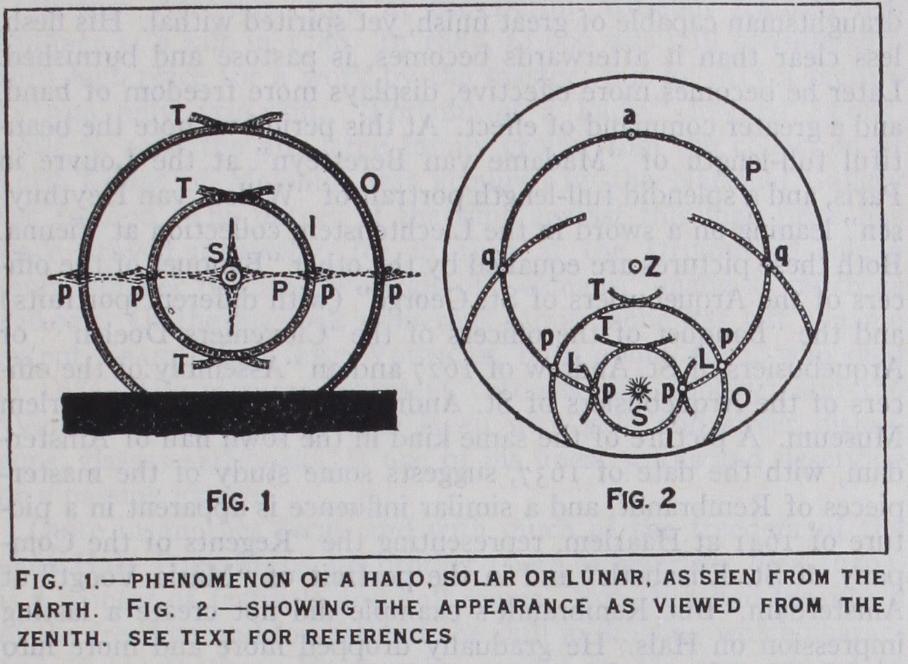

Coronae are of frequent occurrence, but the halo, particularly of well-developed form, is rare except in polar regions. Here they attain great brilliance and complexity. (For illustrations of vari ous types of halos see Met. Office Observer's Handbook.) The phenomenon of a halo, solar or lunar, as seen from the earth, is represented in fig. 1; fig. 2 is a diagrammatic sketch showing the appearance as viewed from the zenith; though only in very excep tional circumstances are all the parts visible. Encircling the lumi nary (S), are two circles, the "inner halo" (I) and the "outer halo" (0), having radii of about 22° and 46°, and usually exhibit ing confused spectrum colours with a decided red tint on the inside. Passing through the luminary and parallel to the horizon, there is a luminous white ring, the parhelic circle (P), on which a number of images of the sun or moon appear (four of these are indicated on the figures by means of the letter p) but the images at 46° are very rare. The most brilliant are situated at the inter sections of the inner halo and the parhelic circle and are known as parhelia, or "mock-suns" (Gr. irap6., beside, and i)Xtos, the sun), or as paraslenae, "mock-moons" (Gr. QEXim, the moon). The parhelia are most brilliant when the sun is low; as it rises they pass slightly outside the halo and exhibit flaming tails. The other images on the parhelic circle are the paranthelia (q) and the an thelion (a) (Gr. av-ri, opposite). Paranthelia are situated at from to 140° of parhelic arc from the sun while the anthelion is at the anti-solar point and is a patch of white light often exceeding in size the apparent diameter of the sun. From the parhelia of the inner halo two arcs (L) curve towards the outer halo. These "arcs of Lowitz" were first described in 1794 by Johann Tobias Lowitz (1757-1804). Arcs (T), tangential to the visible upper and lower parts of each halo, also occur, and in the case of the inner halo they may be prolonged and joined to form a luminous closed curve, quasi-elliptical in shape.

The explanation of halos originated with Rene Descartes, who correctly ascribed their formation to the effects of ice-crystals. This theory was adopted by Edme Mariotte, Henry Cavendish and Thomas Young, who explained the various parts of the halo, though sometimes in a somewhat arbitrary manner. Subsequently J. G. Galle and A. Bravais completely demonstrated the general validity of the theory. Bravais' memoir, published in the Journal de l'Ecole royale polytechnique (1847), still ranks as the classic on halos.

Ice-crystals exist only in high clouds ; the type usually associated with halos is the cirro-nebula. In this the normal form of ice crystal is an upright hexagonal prism either elongated as a needle or flattened like a thin plate. Three refracting angles become pos sible : 120° between two adjacent prism faces, 60° between two alternate prism faces, and 90° between a prism face and the base. If innumerable numbers of such crystals fall in any manner be tween the observer and the sun, there will always be some prisms whose alternate faces are traversed by a ray of light, and this would be refracted. Mariotte showed that the inner halo repre sented by the crowding together of refracted rays is the position of minimum deviation. This approximately equals the minimum deviation ) produced by an ice prism whose refractory angle is 60°. As the angle of minimum deviation is smaller for the less refrangible red rays than for the violet, the halo will be coloured red on the inside. Henry Cavendish similarly explained the halo of 46° as being the result of refraction by faces inclined at 90°. The impurity of the colours, chiefly consequent on oblique refrac tion, results in a well-marked red tint with but mere traces of green and blue, while the external ring of each halo is nearly white; the 46° halo is broader and less luminous.

The two halos admit of explanation without assigning any par ticular arrangement to the ice-crystals. Nevertheless, certain distributions will predominate, for the crystals will tend to fall so as to offer the least resistance to their motion, a needle-shaped crystal tending to keep its axis vertical, a plate-shaped crystal to keep its axis horizontal. Young explained the parhelic circle as caused by reflection from the vertical faces of the long prisms and the bases of the short ones. If the vertical faces become very numerous, the eye will perceive a white horizontal circle. Reflec tion from an excess of horizontal faces gives rise to a luminous vertical circle passing through the sun, but this appearance is of infrequent occurrence.

The parhelia, according to Mariotte, are caused by refraction through a pair of alternate faces of a vertical prism. When the sun is on horizon the rays fall upon the principal section of the prisms; the minimum deviation for such rays is 22°, and conse quently the parhelia are not only on the inner halo, but also on the parhelic circle. As the sun rises, the rays enter the prisms more and more obliquely, and the angle of minimum deviation increases; but, since the emergent ray and the incident ray make the same angle with the refracting edge, the parhelia will remain on the parhelic circle, but gradually recede from the inner halo. The different values of the angle of minimum deviation for differ ently coloured rays will give rise to spectrum colours, the red being nearest the sun, while farther away the overlapping of the spectra produces a long luminous white tail sometimes extending for a space of nearly 20°. The "arcs of Lowitz" have been ex plained by Galle and Bravais as consequent on small oscillations of the vertical prisms, but the theory has only been imperfectly verified.

The tangential arcs were explained by Young as being caused by thin plates with their axes horizontal, refraction taking place through alternate faces. If there are many of these plates then their axes will lie in all possible horizontal directions and conse quently give rise to a continuous series of parhelia which touch externally in the inner halo, both above and below, and under cer tain conditions (such as the requisite altitude of the sun) form two closed elliptical curves; generally, however, only the upper and lower portions are seen. The tangential arcs to the halo of 46° are due to refraction through faces inclined at 90° ; these arcs occur more frequently and are of greater brilliance than the arcs.

The paranthelia (q) may be caused by two internal or two external reflections. A pair of equilateral triangular prisms having a common face, or a stellate crystal formed by the symmetrical interpenetration of two equilateral triangular prisms, permits of two internal reflections by faces inclined at 12o° (producing a total deviation of and so gives rise to two white images of the sun each at an angular distance of from it. Double internal reflection by an equilateral triangular prism would form a single coloured image on the parhelic circle at about 98° from the sun. The I20° and 98° angular distances result only when the sun is on the horizon ; they increase as it rises.

The anthelion may be explained as being caused by two internal reflections of the solar rays by a hexagonal lamellar prism of ice having its axis horizontal and one of the diagonals of its base vertical. The emerging rays are parallel to their original direction and form a bright patch of light on the parhelic circle diametrically opposite to the sun. (See also MIRAGE.)