Radiation

RADIATION 37. It was at one time supposed that there were three distinct kinds of radiation—thermal, luminous and actinic, combined in the radiation from a luminous source such as the sun or a flame. The first gave rise to heat, the second to light and the third to chemical action. The three kinds were partially separated by a prism, the actinic rays being generally more refracted, and the thermal rays less refracted than the luminous. This conception arose very naturally from the observation that the feebly lumi nous blue and violet rays produced the greatest photographic effects, which also showed the existence of dark rays beyond the violet, whereas the brilliant yellow and red were practically with out action on the photographic plate. A thermometer placed in the blue or violet showed no appreciable rise of temperature, and even in the yellow the effect was hardly discernible. The effect in creased rapidly as the light faded towards the extreme red, and reached a maximum beyond the extreme limits of the spectrum (Herschel), showing that the greater part of the thermal radiation was altogether non-luminous.

It is now a commonplace that chemical action, colour sensation and heat are merely different effects of one and the same kind of radiation, the particular effect produced in each case depending on the frequency and intensity of the vibration, and on the nature of the substance on which it falls. When radiation is completely absorbed by a black substance, it is converted into heat, the quan tity of heat produced being equivalent to the total energy of the radiation absorbed, irrespective of the colour or frequency of the different rays. The actinic or chemical effects, on the other hand, depend essentially on some relation between the period of the vibration and the properties of the substance acted on. The rays producing such effects are generally those which are most strongly absorbed. The spectrum of chlorophyll, the green col ouring matter of plants, shows two very strong absorption bands in the red. The red rays of corresponding period are found to be the most active in promoting the growth of the plant. The chemically active rays are not necessarily the shortest. Even photographic plates may be made to respond to the red rays by staining them with pinachrome or some other suitable dye. The action of light rays on the retina is closely analogous to the action on a photographic plate. The retina, like the plate, is sensitive only to rays within certain restricted limits of frequency. The limits of sensitiveness of each colour sensation are not exactly defined, but vary slightly from one individual to another, espe cially in cases of partial colour-blindness, and are modified by conditions of fatigue. We are not here concerned with these im portant physiological and chemical effects of radiation, but rather with the question of the conversion of energy of radiation into heat, and with the laws of emission and absorption of radiation in relation to temperature. We may here also assume the identity of visible and invisible radiations from a heated body in all their physical properties.

It has been abundantly proved that the invisible rays, like the visible, (r) are propagated in straight lines in homogeneous media; (2) are reflected and diffused from the surface of bodies according to the same law; (3) travel with the same velocity in free space, but with slightly different velocities in denser media, being subject to the same law of refraction; (4) exhibit all the phenomena of diffraction and interference which are characteris tic of wave-motion in general ; (5) are capable of polarization and double refraction; (6) exhibit similar effects of selective absorp tion. These properties are more easily demonstrated in the case of visible rays on account of the great sensitiveness of the eye. But with the aid of the thermopile or other sensitive radiom eter, they may be shown to belong equally to all the radiations from a heated body, even such as are 3o to 5o times slower in frequency than the longest visible rays. The same physical prop erties have also been shown to belong to electromagnetic waves excited by an electric discharge, whatever the frequency, thus including all kinds of aethereal radiation in the same category as light.

38. Theory of Exchanges.—The apparent concentration of cold by a concave mirror, observed by G. Baptista Porta and re discovered by M. A. Pictet, led to the enunciation of the theory of exchanges by Pierre Prevost in r 79r. Prevost's leading idea was that all bodies, whether cold or hot, are constantly radiating heat. Heat equilibrium, he says, consists in an equality of ex change. When equilibrium is interfered with, it is re-established by inequalities of exchange. If into a locality at uniform tempera ture a refracting or reflecting body is introduced, it has no effect in the way of changing the temperature at any point of that local ity. A reflecting body, heated or cooled in the interior of such an enclosure, will acquire the surrounding temperature more slowly than would a non-reflector, and will less affect another body placed at a little distance, but will not affect the final equality of temperature. Apparent radiation of cold, as from a block of ice to a thermometer placed near it, is due to the fact that the ther mometer being at a higher temperature sends more heat to the ice than it receives back from it. Although Prevost does not make the statement in so many words, it is clear that he regards the radiation from a body as depending only on its own nature and temperature, and as independent of the nature and presence of any adjacent body.

Heat equilibrium in an enclosure of constant temperature such as that postulated by Prevost, has often been regarded as a consequence of Carnot's principle. Since difference of tempera ture is required for transforming heat into work, no work could be obtained from heat in such a system, and no spontaneous changes of temperature can take place, as any such changes might be utilized for the production of work. This line of reasoning does not appear quite satisfactory, because it is tacitly assumed, in the reasoning by which Carnot's principle was established, as a result of universal experience, that a number of bodies within the same impervious enclosure, which contains no source of heat, will ultimately acquire the same temperature, and that difference of temperature is required to produce flow of heat. Thus although we may regard the equilibrium in such an enclosure as being due to equal exchanges of heat in all directions, the equal and op posite streams of radiation annul and neutralize each other in such a way that no actual transfer of energy in any direction takes place. The state of the medium is everywhere the same in such an enclosure, but its energy of agitation per unit volume is a function of the temperature, and is such that it would not be in equilibrium with any body at a different temperature.

39. "Full" and Selective Radiation.—Correspondence of Emission and Absorption. The most obvious difficulties in the way of this theory arise from the fact that nearly all radiation is more or less selective in character, as regards the quality and frequency of the rays emitted and absorbed. It was shown by J. Leslie, M. Melloni and other experimentalists that many sub stances such as glass and water, which are very transparent to visible rays, are extremely opaque to much of the invisible radia tion of lower frequency ; and that polished metals, which are per fect reflectors, are very feeble radiators as compared with dull or black bodies at the same temperature. If two bodies emit rays of different periods in different proportions, it is not at first sight easy to see how their radiations can balance each other at the same temperature.

The key to all such difficulties lies in the fundamental concep tion, so strongly insisted on by Balf our Stewart, of the absolute uniformity (qualitative as well as quantitative) of the full or complete radiation stream inside an impervious enclosure of uni form temperature. It follows from this conception that the pro portion of the full radiation stream absorbed by any body in such an enclosure must be exactly compensated in quality as well as quantity by the proportion emitted, or that the emissive and ab sorptive powers of any body at a given temperature must be pre cisely equal. A good reflector, like a polished metal, must also be a feeble radiator and absorber. Of the incident radiation it ab sorbs a small fraction and reflects the remainder, which together with the radiation emitted (being precisely equal to that ab sorbed) makes up the full radiation stream. A partly transparent material, like glass, absorbs part of the full radiation and trans mits part. But it emits rays precisely equal in quality and in tensity to those which it absorbs, which together with the trans mitted portion make up the full stream.

A thin platinum tube heated by an electric current appears feebly luminous as compared with a blackened tube at the same temperature. But if a small hole is made in the side of the pol ished tube, the light proceeding through the hole appears brighter than the blackened tube, as though the inside of the tube were much hotter than the outside, which is not the case to any appre ciable extent if the tube is thin. The radiation proceeding through the hole is nearly that of a perfectly black body if the hole is small. If there were no hole the internal stream of radiation would be exactly that of a black body at the same temperature however perfect the reflecting power, or however low the emissive power of the walls, because the defect in emissive power would be exactly compensated by the internal reflection.

Balfour Stewart gave a number of striking illustrations of The qualitative identity of emission and absorption of a substance. Pieces of coloured glass placed in a fire appear to lose their colour when at the same temperature as the coals behind them, because they compensate exactly for their selective absorption by radiat ing chiefly those colours which they absorb. Rocksalt is remark ably transparent to thermal radiation of nearly all kinds, but it is extremely opaque to radiation from a heated plate of rock salt, because it emits when heated precisely those rays which it absorbs. A plate of tourmaline cut parallel to the axis absorbs almost completely light polarized in a plane parallel to the axis, but transmits freely light polarized in a perpendicular plane. When heated its radiation is polarized in the same plane as the radiation which it absorbs. In the case of incandescent vapours, the exact correspondence of emission and absorption as regards wave-length or frequency of the light emitted and absorbed forms the foundation of the science of spectrum analysis. Fraunhofer had noticed the coincidence of a pair of bright yellow lines seen in the spectrum of a candle flame with the dark D lines in the solar spectrum, a coincidence which was afterwards more ex actly verified by W. A. Miller. Foucault found that the flame of the electric arc showed the same lines bright in its spectrum, and proved that they appeared as dark lines in the otherwise continu ous spectrum when the light from the carbon poles was trans mitted through the arc. Stokes gave a dynamical explanation of the phenomenon and illustrated it by the analogous case of reso nance in sound. Kirchhoff completed the explanation (Phil. Meg., 186o) of the dark lines in the solar spectrum by showing that the reversal of the spectral lines depended on the fact that the body of the sun giving the continuous spectrum was at a higher temperature than the absorbing layer of gases surrounding it.

Whatever be the nature of the selective radiation from a body, the radiation of light of any particular wave-length cannot be greater than a certain fraction E of the radiation R of the same wave-length from a black body at the same temperature. The fraction E measures the emissive power of the body for that par ticular wave-length, and cannot be greater than unity. The same fraction, by the principle of equality of emissive and absorptive powers, will measure the proportion absorbed of incident radia tion R'. If the black body emitting the radiation R' is at the same temperature as the absorbing layer, R=R', the emission balances the absorption, and the line will appear neither bright nor dark. If the source and the absorbing layer are at different temperatures, the radiation absorbed will be ER', and that trans mitted will be R'–ER'. To this must be added the radiation emitted by the absorbing layer, namely ER, giving R'–E(R'–R). The lines will appear darker than the background R' if R' is greater than R, but bright if the reverse is the case. The D lines are dark in the sun because the photosphere is much hotter than the reversing layer. They appear bright in the candle-flame be cause the outside mantel of the flame, in which the sodium burns and combustion is complete, is hotter than the inner reducing flame containing the incandescent particles of carbon which give rise to the continuous spectrum. This qualitative identity of emission and absorption as regards wave-length can be most exactly and easily verified for luminous rays, and we are justified in assuming that the relation holds with the same exactitude for non-luminous rays, although in many cases the experimental proof is less complete and exact.

40. Relation Between Radiation and Temperature.—As suming, in accordance with the reasoning of Balfour Stewart and Kirchhoff, that the radiation stream inside an impervious enclo sure at a uniform temperature is independent of the nature of the walls of the enclosure, and is the same for all substances at the same temperature, it follows that the full stream of radiation in such an enclosure, or the radiation emitted by an ideal black body or full radiator, is a function of the temperature only. The form of this function may be determined experimentally by observing the radiation between two black bodies at different temperatures, which will be proportional to the difference of the full radiation streams corresponding to their several temperatures. The law now generally accepted was first proposed by Stefan as an em pirical relation.

Tyndall had found that the radiation from a white hot plati num wire at 1,200° C was 11.7 times its radiation when dull red at 525° C. Stefan (Wien. Akad. Ber., 1879, 79, p. 421) noticed that the ratio I r.7 is nearly that of the fourth powers of the absolute temperatures as estimated by Tyndall. On making the somewhat different assumption that the radiation between two bodies varied as the difference of the fourth powers of their abso lute temperatures, he found that it satisfied approximately the experiments of Dulong and Petit and other observers. According to this law the radiation between a black body at a temperature T and a black enclosure or a black radiometer. at a temperature should be proportional to The law was very simple and convenient in form, but it rested so far on very insecure foundations. The temperatures given by Tyndall were merely estimated from the colour of the light emitted, and might have been some hundred degrees in error. We now know that the radiation from polished platinum is of a highly selective character, and varies more nearly as the fifth power of the absolute tempera ture. The agreement of the fourth power law with Tyndall's ex periment appears therefore to be due to a purely accidental error in estimating the temperatures of the wire. Stefan also found a very fair agreement with Draper's observations of the intensity of radiation from a platinum wire, in which the temperature of the wire was deduced from the expansion. Here again the apparent agreement was largely due to errors in estimating the temperature, arising from the fact that the coefficient of expansion of platinum increases considerably with rise of temperature.

So far as the experimental results available at that time were concerned, Stefan's law could be regarded only as an empiri cal expression of doubtful significance. But it received a much greater importance from theoretical investigations which were even then in progress. James Clerk Maxwell (Electricity and Magnetism, 1873) had shown that a directed beam of electro magnetic radiation or light incident normally on an absorbing surface should produce a mechanical pressure equal to the energy of the radiation per unit volume. A. G. Bartoli (1875) took up this idea and made it the basis of a thermodynamic treatment of radiation. P. N. Lebedew in 1900, and E. F. Nichols and G. F. Hull in 1901, proved the existence of this pressure by direct experiments. L. Boltzmann (1884) employing radiation as the working substance in a Carnot cycle, showed that the energy of full radiation at any temperature per unit volume should be pro portional to the fourth power of the absolute temperature.

The proof given by Boltzmann may be somewhat simplified if we observe that full radiation in an enclosure at constant tempera ture behaves exactly like a saturated vapour, and must therefore obey Carnot's or Clapeyron's equation (see THERMODYNAMICS). The radiation-pressure at any temperature is a function of the temperature only, like the pressure of a saturated vapour. If the volume of the enclosure is increased by any finite amount, the temperature remaining the same, radiation is given off from the walls so as to fill the space to the same pressure as before. The heat absorbed when the volume is increased corresponds with the latent heat of vaporization. In the case of radiation, as in the case of a vapour, the latent heat consists partly of internal energy of formation and partly of external work of expansion at constant pressure. Since in the case of full or undirected radiation the pres sure is one-third of the energy per unit volume, the external work for any expansion is one-third of the internal energy added. The latent heat absorbed is, therefore, four times the external work of expansion. Since the external work is the product of the pressure P and the increase of volume V, the latent heat per unit increase of volume is four times the pressure. But by Carnot's equation the latent heat of a saturated vapour per unit increase of volume is equal to the rate of increase of saturation-pressure per degree divided by Carnot's function or multiplied by the absolute tem perature. Expressed in symbols we have, (14) where (dP/dT) represents the rate of increase of pressure. This equation shows that the percentage rate of increase of pressure is four times the percentage rate of increase of temperature, or that if the temperature is increased by 1 %, the pressure is increased by 4%. This is equivalent to the statement that the pressure varies as the fourth power of the temperature, a result which is mathematically deduced by integrating the equation.

41• Experimental Verification of the Fourth Power Law. —The verification of this law requires (1) a black body or bodies capable of emitting full radiation at a series of different tempera tures over an extended range, (2) a thermometer or thermometers capable of measuring these temperatures on the absolute scale, (3) a bolometer or thermopile capable of giving accurate relative values of the intensity of the radiation emitted in each case. These conditions were approximately satisfied by the experiments of Schneebeli (tiVied. Ann., 1884), who employed an air ther mometer heated to various temperatures in a furnace, and ob served the radiation from the bulb through a small aperture in the walls of the furnace. With this arrangement the radiation observed would be nearly that of a black body, but the verifica tion was rather rough in some respects. Measurements by J. T. Bottomley, A. Schleiermacher, L. C. H. F. Paschen and others, of the radiation from electrically heated platinum, failed to give results in agreement with the fourth power law on account of variations in the quality of the radiation, but greatly extended and improved methods of measuring radiation in other respects.

The most complete series of experiments, covering the range of the gas thermometer at the time available, were those of O. R. Lummer and E. Pringsheim (Ann. Phys., 1897). They used a black body heated by steam at ioo° C, for standardizing their bolometer, and, as their radiator, a black body consisting of a copper sphere heated in a salt bath for the range 200° to 600° C, and an iron cylinder heated in a gas muffle for the range 600° to 1,250° C. The temperatures were taken with a high range mercury thermometer, and with thermocouples, corrected to the gas scale by direct comparison with a gas thermometer up to 1,15o° C. One of the chief experimental difficulties of this investigation is the wide range of variation of the intensity of the radiation to be measured, which is nearly 45o times as great at 1,250° C as at too° C. They employed a very sensitive form of bolometer (see § 42), and a galvanometer capable of giving a deflection of 336mm. under standard conditions, with a beam of radiation i6mm. square at a distance of 633mm. from the black body at C. For the higher intensities it was necessary to reduce the sensitivity in a known ratio by varying the distance of the bolom eter from the source, and the current in the bolometer circuit. The results for the relative intensities agreed on the average to about 1 % with the fourth power law over the whole range of the observations. The law has since been verified up to 1,500° C by extending the range of the gas thermometer and the calibra tion of the thermocouples.

42. Sensitive Radiometers.—The term radiometer may be applied to any instrument adapted for measuring radiation, but we are here concerned chiefly with those types which are equally sensitive to radiant energy of all the wavelengths present in the radiation from a hot body. We may therefore omit the selenium cell which is very sensitive to luminous radiation, and the photo electric cell for actinic rays, since these are comparatively insensi tive to the infra-red rays, and do not satisfy the condition of measuring total energy irrespective of wavelength. The instru ments chiefly employed at the present time for measurements of heat radiation, are the thermopile and the bolometer, the action of which depends on the same principles as those involved in the construction and operation of the corresponding types of elec trical thermometers, namely the thermocouple and the electrical resistance thermometer, the theory of which is more fully dis cussed in the article THERMOMETRY. The thermopile and bolom eter are in fact essentially electrical thermometers, with sensi tive receiving surfaces for the absorption of radiation, and espe cially designed for measuring the small differences of temperature thereby produced. The sensitivity and accuracy of these instru ments depend to a great extent on the galvanometer and electrical measuring apparatqs with which they are employed.

One of the oldest and most sensitive radiometers is the Mellon thermopile, the invention of which led to so many advances in the theory and measurement of radiation. Sensitivity is secured by using antimony and bismuth alloys (A and B), a single couple of which may give as much as 120 microvolts for a difference of temperature of 1 ° C between the hot and cold junctions. With couples connected in a continuous series A–B–A–B–A and so on packed as usual in the form of a cube with alternate junc tions on opposite faces, an electromotive force of 1 2 millivolts would be obtainable per 1 ° C difference of temperature between the receiving surfaces of the pile. The chief defect of this type of instrument in practice is that it has a large thermal capacity owing to its massive construction, and takes a long time to reach its maximum temperature. For many purposes quickness of action is quite as important as sensitivity in millivolts per degree, and the accuracy obtainable depends to a great extent on constancy of zero. In such cases the Melloni pile will be a most unsuitable instrument to employ, though it is still often used for demonstra tion purposes.

The conditions affecting quickness and constancy were first clearly elucidated by C. V. Boys (Phil. Trans. 1888) in the con struction of his radiomicrometer, in which the thermopile and galvanometer were combined in a single instrument. This was effected by attaching a very light A–B couple to a loop of copper wire suspended between the poles of a powerful magnet by means of a fine quartz fibre, which made it possible to combine the ad vantage of maximum deflection for weak sources of radiation with quickness of action and constancy of zero. A similar ar rangement was adopted some years later by W. Duddell in his thermo-galvanometer, for measuring small alternating currents. The current to be measured is passed through a small heater fixed close below the suspended thermocouple, the deflections of which are approximately proportional to the square of the cur rent. The radio-micrometer is essentially the same instrument except that the suspended thermocouple is heated by radiation incident on a blackened disc of copper or silver foil, and that its constant is determined by exposure to a known source of radia tion, such as a standard candle at a considerable distance. The instrument must be set up like a sensitive galvanometer and care fully levelled on a good foundation in a permanent position, and the radiation to be measured must be brought to the receiver in a horizontal direction. In this respect the combination of' the thermopile and sensitive galvanometer in a single instrument is less convenient in practice than the use of a separate thermopile in conjunction with a fixed galvanometer, since in the latter case the thermopile can be adjusted in any desired position inde pendently of the galvanometer, and the sensitivity may easily he altered in a known ratio according to requirements by varying the resistance in the circuit without changing the position of either source or receiver.

The bolometer invented by S. P. Langley (Proc. Amer. Acad., 1881) depends for its action on change of electrical resistance, and consists essentially of a pair of grids of thin blackened foil of nearly equal resistance balanced one against the other in a Wheat stone bridge. Both are equally affected by changes in the tempera ture of the instrument, but if one grid is exposed to radiation while the other is screened, the resulting difference of temperature be tween them produces a current through the galvanometer approxi mately proportional to the intensity of the radiation. The whole exposed area of the grid constitutes the receiving surface, and extreme quickness of action can be secured by using very thin foil. The bolometer permits a wide range of variation of sensi tivity since (in addition to other methods available with the ther mopile) the current through the grids may be increased with a proportional increase in the deflection of the galvanometer. For this reason the sensitivity of a bolometer may considerably exceed that of a thermopile under otherwise similar conditions. There is, however, a practical limit to the increase of sensitivity thus obtain able, owing to the heating effect of the current which produces a rise of temperature in the grids proportional to the square of the current. When this becomes excessive, the zero is liable to wander and no further improvement in accuracy of measurement can be gained. The effect is most marked with a "linear" bolometer, con sisting of a single strip of high resistance, as employed by Langley for measuring the intensity of the absorption lines in the infra-red spectrum. The rise of temperature due to a given current will be many times greater in a single strip than in a grid of many strips with the same resistance but a much larger surface for dissipating the heat generated.

A linear thermopile, in which all the sensitive junctions are arranged in a vertical line, is entirely free from this source of trouble and is generally superior to the bolometer in point of sta bility of zero. Fig. i i illustrates the construction of the Moll lin ear thermopile which is probably the most perfect instrument of this type in respect to constancy of zero as well as quickness of action. There are 20 couples ar ranged with their hot junctions in a vertical line behind the centre of the slit. The metals employed are the alloys constantan and manganin, both of which possess the property that their resistance does not vary appreciably with temperature. These alloys have the required mechanical proper ties and can be rolled into very thin strips, which afford excellent receiving surfaces and respond with extreme quickness. One half of each strip consists of constantan and the other half of manganin as indicated in the figure by the shading. The strips are con nected in a continuous series, C–M–C–M–C and so on, the cold junctions on either side being soldered to copper studs fixed in insulating blocks at right angles to the plane of the strips. The function of these studs is to keep the cold junctions at a uniform temperature as nearly as possible the same as that of the en closing case. Great constancy of zero and steadiness of deflec tion is thus obtained. Thus although the thermoelectric power of a single constantan-manganin couple is only about 4o microvolts per degree, or less than a third of that obtainable with the anti mony-bismuth alloys (which are brittle and difficult to work) the superior quickness and constancy and facility of construction of the Con-Mn pile make the latter a more accurate and convenient instrument in practice.

In measuring the intensity of radiation at a distance from the source, where there is no restriction on the area of the beam re ceived, the bolometer has the advantage that it can easily be made of any desired area, and that increase of area permits an increase of sensitivity. This condition cannot be satisfied easily in practice with a thermopile since the multiplication of couples involves a corresponding increase of resistance ; but in dealing with images, such as spectral lines, of limited area, the thermocouple has the advantage that its sensitive receiving surface can be made to coincide with that of the image to be measured, as in the coronal pile (Proc. Roy. Soc., 1905) for observing the sun's corona. Thus in the extreme case of a point image, such as that of a star, the single couple has a great advantage over the bolometer, which could not easily be made of the required size. By using very small single couples enclosed in a vacuum to reduce external loss of heat, W. W. Coblentz (Lick Observatory, 1915) succeeded in obtaining remarkably accurate measurements of the relative thermal inten sities of star images in a large reflecting telescope. The vacuum thermopile recently devised by Moll, with a differential pair of junctions enclosed in a vacuum, would probably be well suited for this kind of work, as the effect of sky radiation would be compen sated very accurately.

The Crookes' radiometer, with a delicately suspended vane in a vacuum of about o.oamm., as improved by Nichols, can be made nearly equal in sensitivity to the radiomicrometer of Boys, but has the disadvantage of requiring the radiation to be introduced through a window, which may in many cases give rise to uncer tainty due to selective absorption, in addition to the difficulty of maintaining a constant vacuum.

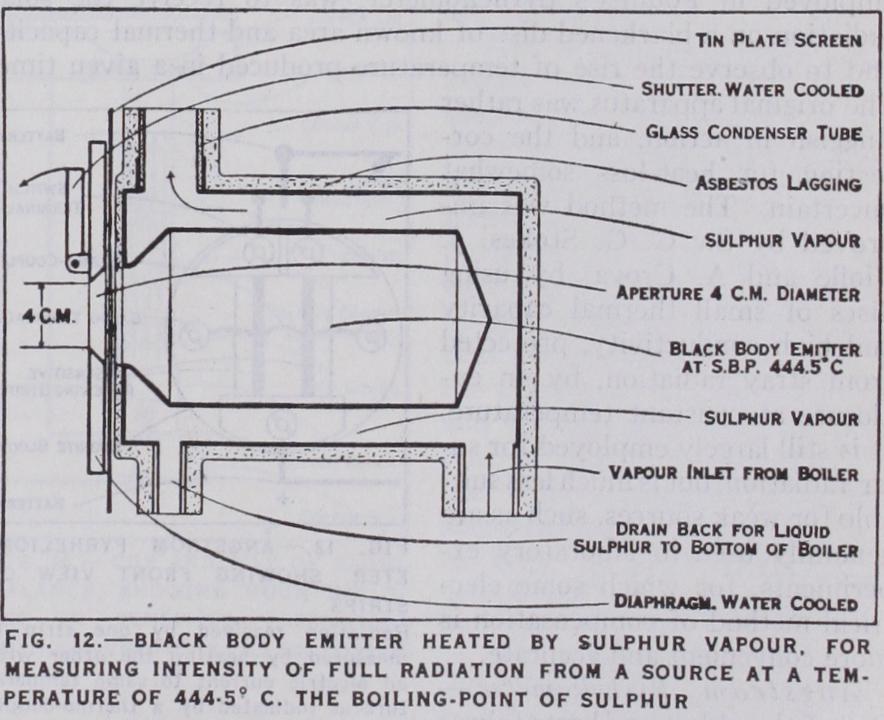

43. Absolute Measurement of Radiation.—The absolute measurement of the constant of radiation in the fourth-power is required for estimating the quantity of radiation R emitted per second per unit area by a black surface at the absolute tem perature T. The law having been verified qualitatively, as pre viously described, by observing relative values at different tem peratures, it suffices for the determination of the constant o to select one particular temperature of the source, and to observe the intensity of the radiation received at a known distance with a receiver capable of giving the result in absolute measure, such as watts per sq.cm., or sec. It is first necessary that the temperature of the emitter should be uniform and accurately known. For this reason a black body enclosure at too° C or T=373.1 is commonly selected. The objection to this is that the intensity of the radiation is comparatively feeble and the quantity of heat to be measured inconveniently small as compared with accidental errors. A high temperature such as T=1273° gets over this difficulty, but such temperatures are not known with sufficient accuracy, and are not easily regulated with the necessary uni formity and constancy. It appears best to select an intermediate temperature, such as the boiling point of sulphur (S.B.P.) at C or T=717.6°, which has been determined with great care, and is easily maintained constant.

Fig. 12 shows the essential points of a black body emitter em ployed for this purpose. The black body consists of a double walled enclosure constructed of sheet iron with brazed or welded joints, which must be absolutely tight to prevent any escape of the vapour. The sulphur is boiled in an iron boiler located in a fume cupboard at a lower level, and the vapour is brought up to the ap paratus through a long iron tube to avoid any possibility of super heating. When the sulphur boils, the heavy brown vapour soon makes its appearance in the glass condenser tube at the top of the apparatus. This tube is open at the top, and is exposed without lagging for a height of two or three feet. The boiler flame is regulated to keep the level of the vapour constant about half way up the tube. The condensed liquid flows back through a small tube to the bottom of the boiler, and the apparatus will work for days with hardly any attention. The actual temperature inside the en closure is observed occasionally with a long platinum thermometer, and is always a few tenths of a degree lower than that of the va pour, as deduced from the height of the barometer, owing to loss by radiation. The inside of the enclosure is usually blackened in the first instance with platinum black, but soon becomes coated in any case with a protecting film of black oxide of iron, which is generally black enough for the purpose. The emitted beam is defined by an accurately turned aperture in a blackened dia phragm, cooled by a copious circulation of water at or near the atmospheric temperature.

The method of taking an observation consists in exposing the receiver, at a distance d from the diaphragm along the axis of the aperture, to the full normal beam of radiation, and taking a read ing of the heat received. The aperture is then closed by the water cooled shutter shown in the figure, and a zero reading is taken. The effect of closing the shutter is to substitute for the beam of full radiation at the temperature T of the enclosure, a beam from an exactly equal area of the shutter at the temperature which is the same as that of the diaphragm. The observed difference be tween the two readings gives the value of as required in the equation, and eliminates any accidental stray radiation, which may affect the zero of the receiver, but is not altered by closing the shutter. If T = 717.6° and = 29o°, the correction for Too is less than 1.6%, so that a defect of 5% in the effective black ness of the diaphragm or shutter would give an error of less than I in moo in the result for the constant cr, and it is not necessary to know the value of with great accuracy. The case is quite different, however, in using a black body at ioo° C or 373.1°A in the same manner. The correction for would then amount to nearly 37%, or 23 times larger, and a defect of 5% in the black ness of the shutter might produce an error of nearly 2% in the result. This fact, in addition to the other difficulties above men tioned, has often led to appreciable errors in the use of a black body at too° C for purposes of reference, and is one of the chief reasons why it is desirable to use a black body at a reasonably high temperature for the determination of the constant a. Accidental errors of this kind, due to invisible reflections, and stray radiation, are most perfectly avoided by completely enclosing the receiver in a water-cooled aluminium casting (aluminium for lightness and high conductivity) at the same temperature as the diaphragm and shutter. The casting has a removable lid permitting easy access for preliminary measurements and adjustments of distance, etc., but this method is so elaborate that it has seldom been attempted. It is also essential to exclude products of combustion such as CO, and which are highly absorbent for infra-red radiation. 44. Absolute Radiometers.—The measurement of the radia tion in absolute units is a more difficult part of the problem than that of securing a good approximation to full radiation at a known temperature. Instruments designed for absolute measurement were first developed for measuring the intensity of solar radia tion, and were called pyrheliometers. The usual method, as first employed in Pouillet's pyrheliometer, was to receive the solar radiation on a blackened disc of known area and thermal capacity and to observe the rise of temperature produced in a given time. The original apparatus was rather sluggish in action, and the cor rection for heat-loss somewhat uncertain. The method was im proved by Sir G. G. Stokes, J.

Violle and A. Crova, by using discs of small thermal capacity and high conductivity, protected from stray radiation, by an en closure at constant temperature.

It is still largely employed for so lar radiation, but is much less suit able for weak sources, such as are generally used in laboratory ex periments, for which some elec trical method of compensation is i more convenient and accurate.

Angstrom Pyrheliometer.

One of the oldest and best of these compensation methods was first devised by K. Angstrom (189o) for measuring solar radiation. His pyrheliometer is illustrated in figs. 13 and 14, and depends on balancing the radiation by elec tric heating. The front view, fig. 13, shows the pair of blackened strips of very thin manganin, 2cm. long and 2mm. wide, one of which is exposed to the radiation to be measured while the other is heated to the same temperature by an electric current. In this case the heat received from the radiation by one strip would evi dently be equal to that generated by the current in the other, pro vided that the two were alike in all respects. Thus if R' is the radiant heat absorbed per sq.cm., b the breadth of the strip, C the current in amperes and r the resistance in ohms per cm., the value of R' in watts per sq.cm. is given by the simple relation, Or/b. The ebonite block carrying the strips and their con necting terminals is fitted in a brass tube the front of which is closed by a cap with two slits corresponding in position with the strips. A swivelling shutter behind the cap permits the screening of either strip. The current is turned on the screened strip by the switch at the back and is adjusted by the rheostat until the galvanometer connected to the thermo-couple indicates equality of temperature by absence of de flection. The thermo-couple con sists of a loop of fine constantan wire, the ends of which are con nected to strips of copper foil at tached to the backs of manganin strips as indicated in the diagram of connections (fig. 14). Each copper strip is attached as closely as possible to its manganin strip, but is insulated from it by thin silk paper and shellac. The copper strips provide a reliable attachment for the two junctions of the couple and help to equalize the temperature of the strip. The object of balancing one strip against the other is to make the reading as sensitive as possible, and to eliminate any dis turbances depending on changes of temperature of the case, which would affect both strips equally. To eliminate small differences between the strips, the reading is repeated with the second strip screened and heated by the current while the first is exposed to radiation. The mean of the results is free from errors due to want of symmetry, provided that such errors are small. In this bal ance method of observation the result is practically independent of the accuracy of the galvanometer, but an error of I % in the current C as measured by the ammeter would give an error of. 2% in the result, since it depends on The result also depends on the breadth of the strip b and on its resistance r per cm., both of which are difficult to measure accurately, more especially when the strip is blackened with smoke, which makes the edge somewhat ill defined. In any case the value of R, representing the heat actually absorbed, will depend on the coefficient of absorption of the smoke film, which is generally taken as 98% but may vary somewhat for different wave-lengths and different smoke films.

Kurlbaum's bolometric method can be applied to any sensitive bolometer of suitable construction, and avoids some of the diffi culties of measurement inherent in Angstrom's method, but in troduces others which make it less convenient for solar radiation. The method consists in observing the deflection D of the gal vanometer when the bolometer is exposed to the radiation to be measured and is traversed by the small current c usually employed. The grid is then screened from radiation, and the current is in creased to a larger value C such that the galvanometer gives the same deflection D due to the additional heat generated by the cur rent in the grid. The intensity of the radiation in watts per sq.cm. is given in terms of the resistance r per sq.cm. of the grid by the formula, The difficulty of measuring the width of the strips may be avoided by using a pair of similar grids, adjusted in such a way that the strips of the second are behind the spaces between the strips of the first. The whole area of the grid may thus be utilized, and r is the whole resistance in ohms divided by the area in sq.cm. The factor C/c is required in the formula to allow for the fact that the deflection D of the galvanometer for a given increase of resistance of the grid is directly proportional to the current. The accuracy of measurement of the currents C and c is rather more important than in Angstrom's method, but the bolo metric method avoids the measurement of b and makes that of r very easy. On the other hand it is necessary to balance the bol ometer against manganin resistances which are not appreciably affected by the current C. This makes it impossible to compensate for changes in the temperature of the surroundings in the usual way (by balancing the receiving grid against a precisely similar grid) since both would be equally heated by the current C. Kurl baum employed a black body at Ioo° C as source, and the actual rise of temperature of the grid due to the incident radiation with the small current c was only about a tenth of I° C. The rise of temperature due to increasing the current from c to C would be less than this in the ratio c/C. The successive observations of radiation and current-heating would be unequally affected by any change in the surrounding conditions, and the difficulties of the method make it unsuitable for employment except in the labora tory with weak sources under very steady conditions.

Employing this method Kurlbaum (Wied. Ann., 1898) found the value ergs per sq.cm. per sec., or watts per sq.cm., but this rested on a somewhat doubtful estimate of the absorption coefficient of the bolometer employed, and was raised at a later date (1912) from 5.32 to 5.45• Paschen and Gerlach (Ann. Phys. 1912) employed a modification of Angstrom's method, but with a single strip (in place of a pair of strips) of measured area and resistance, which was alternately exposed to the radiation to be measured and heated by a measured electric current. The rise of temperature of the strip was indicated, and adjusted approximately to the same value in either case, by ob serving the deflection of a galvanometer connected to a linear pile fixed in position close behind the strip but not in contact with it. The method is inferior in some respects to Angstrom's, especially in the absence of a balancing strip, and in its dependence on the accurate observation of successive deflections. On the other hand the single strip employed by Paschen and Gerlach is easier to make than the compound strip employed by Angstrom, and the measurement of its breadth b and resistance r per cm. should be more accurate. They used a linear thermopi'e equal in length to the strip, and deduced the value of r per cm. from measurements of the whole length and resistance, whereas Angstrom measured r by observing the potential difference between a pair of needle point potential terminals fixed at a distance of 'cm. apart, and brought into contact with the central portion of the strip while a measured current was passing through it. This was a delicate oper ation, but was necessitated by the fact that he used a single couple at the centre of the strip, and that there might be some uncer tainty about the resistance of the contacts at the end of the strip, since the compound strip could not be soldered satisfactorily to the terminal plates. Gerlach's later measurements (1916), in which corrections were applied for the imperfect blackness of platinum black and for atmospheric absorption, gave a final value a= 5.8oX i watt per sq.cm. which, though appreciably lower than his original uncorrected value, 5.85, was still nearly 7% higher than Kurlbaum's final value 5.45 by the bolometric method. It was suggested that these discrepancies might be due to in equalities of temperature due to loss of heat by conduction from the ends of the strip. Coblentz and Emerson (Bur. Stds. Bull., 1916) endeavoured to avoid this difficulty by attaching potential terminals to the strip at a short distance from the ends. These terminals tend to cool the strip locally, but they estimate the cooling effect as only about 0.3%. Comparing a number of differ ent receivers of this type they found variations amounting in some cases to 2%, with a probable order of I% for the accuracy of the mean. They gave a final value 5.73 for the constant after ap plying corrections for imperfect blackness and atmospheric ab sorption.

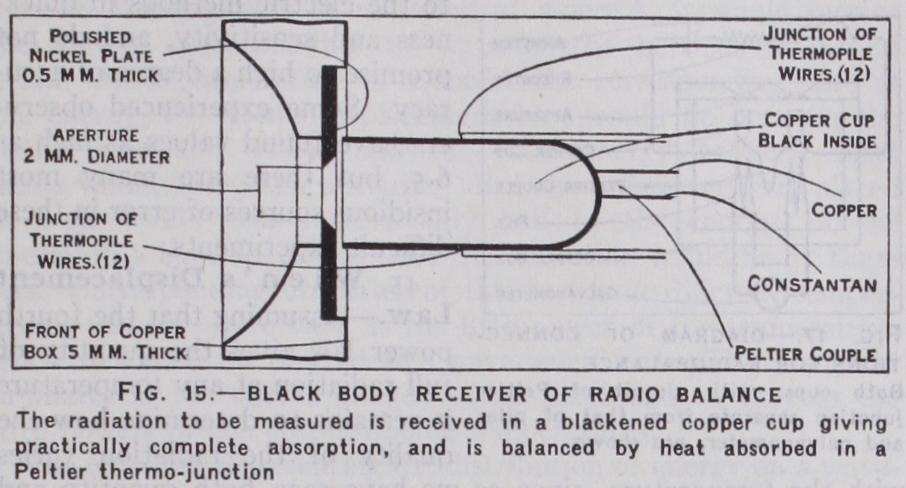

The Radiobalance, employed by Callendar (Proc. Phys. Soc. 1910), was the first serious attempt to eliminate uncertain co efficients of absorption (which depend on the wave-length of the radiation as well as on the blackness and conductivity of the film) by employing a black-body receiver, designed to give complete absorption with an error of less than 0.1%. The construction of this receiver which can be used in any position, is illustrated in the fig. 15, on an enlarged scale. The radiation to be measured is admitted through an optically worked aperture of 2mm. dia. (which is comparatively easy to measure with the requisite de gree of accuracy) and falls on the bottom of a small copper cup, where it is directly compensated by the absorption of heat due to the Peltier effect in a thermojunction formed between the cup and a constantan wire through which a suitable current is passed. Any change of temperature of the cup is indicated by a sensitive galvanometer, connected to a thermopile in which the cup is mounted as shown in fig. 16. The junctions of the pile are in sulated from the cup by thin silk paper and paraffin wax, which is non-hygroscopic, and are bound firmly round the cup with a lapping of fine silk. The pile wires are iron and constantan each 0• 2mm. dia. and are sufficiently stiff to hold the cup securely in place. The cold junctions of the pile are similarly fixed to a copper cylinder screwed to the base of the copper box 5mm. thick enclosing the sensitive parts of the apparatus at a uniform tem perature, which is indicated by a delicate mercury thermometer with its bulb inserted between the two piles. Since it is always desirable to take observations by a balance method (most especially in measuring strong sources of radiation, such as 'cal. per sq.cm. per min., or 0.07 watt per sq.cm., which would give unbalanced deflections of the galvanometer of the order of 7,000mm.) the cup exposed to radiation is balanced against a similarly mounted cup, as indicated in the diagram of connections fig. 17, the piles in which the cups are mounted being connected in opposition in the galvanometer circuit. This method gives very perfect elimination of external disturbances owing to the small size and high conductivity of the copper box in which the two piles are enclosed.

The advantage of using the Peltier effect for the absolute measurement of radiation, in place of the more familiar Joule effect employed in other instru ments such as the Angstrom pyrheliometer, is that heat recep tion can be directly compensated by heat absorption, and that the heat absorbed is proportional to the current C (instead of to and changes sign when the cur rent is reversed. The value of the Peltier coefficient P for a single copper-constantan junction as here employed is approxi mately 12 millivolts, which when multiplied by the current C in amperes gives the heat absorption PC in milliwatts. Thus with an aperture of 2mm. dia. the current required to compensate radia tion of intensity 0.07 watt per sq.cm., which is near the mean for sunshine, is about 200 milliamps. with a single couple. In actual practice the same current C is passed through the Peltier junctions of both cups so that the exposed cup is cooled while the screened cup is heated. This doubles the effect and requires a current of loo milliamps. only, in the case above given, and makes it possible to measure strong sources up to 0.4 watt per sq.cm., without changing the 2mm. aperture.

In taking readings by this method, one cup is exposed to radia tion while the other is screened, and the current is adjusted to reduce the deflection of the galvanometer to zero. After reading the current, the radiation is switched over to the other cup (by moving a shutter close in front of the aperture and behind the tin plate screen in fig. 16) and the current is simultaneously re versed without altering its value. This procedure has the effect of exactly eliminating any small heating effect in the wires conveying the current to the cups, and gives the simple formula R'=2PC/a, for the intensity R' of the radiation received in terms of the aperture a in sq.cm. If the radiation is variable, as is usually the case with sunshine even on the clearest day, it is preferable to keep the current constant and to observe the small residual deflec tions of the galvanometer, which are readily translated into mil liamps. by observing the deflection produced by reversing a small current when both cups are screened. If the piles are not accurately balanced, or if the areas of the apertures are not exactly equal, the appropriate value of the balancing current will be different for the two cups. Any small differences of this kind may be treated in the same way by observing galvanometer deflec tions, but should not exceed a small fraction of i%.

The value of the coefficient P is most easily determined by ob serving the thermoelectric power p of a junction made of the same wires, and multiplying by the absolute temperature T. Both fac tors in the product Tp increase with temperature, so that it is necessary to know the temperature to 0.2° C in order to secure an order of accuracy of 0.1% in R', since the temperature co efficient of P is usually in the neighbourhood of 0.5% per i ° C. A more direct method is to balance the Peltier effect in each cup against the heating effect in a resistance coil fitting the cup. This method affords the most simple and accurate verification of the thermodynamic theory, and measures the effect under working conditions for the actual couples employed. To find the value of v by observing the radiation emitted from a black body such as that illustrated in fig. 12, with a water cooled aperture of radius b, it is necessary to adjust the aperture a of the receiver to be coaxial with that of the emitter and to measure the distance d between their planes. The normal intensity R' as measured by the receiver is given in terms of the black body intensity R in formula (15) by the simple relation which may be found in most textbooks of geometrical optics.

Observations taken with radiobalance D (one of the instruments described in Proc. Phys. Soc. 1910) in conjunction with the black body illustrated in fig. 12, by N. L. Jones gave a mean result 0= 5.69oX watt per sq.cm. The observations were taken at night under favourable conditions, but no correction was applied for atmospheric absorption, as the distance (29 to 33cm.) was not varied sufficiently. Later observations made by Callendar using a black body at 00° C with the same instrument, in which the distance d was varied from 6 to 56cm. under similar conditions, gave a result 5.752 when corrected for atmospheric absorption. The Peltier couple in this instrument was tested by the thermo electric method using samples of the same wires, iron and con stantan respectively. Another balance (E), with a copper-con stantan couple, tested by both methods with consistent results, and corrected for atmospheric absorption in the same way, gave a slightly higher result, 5.766. The differences between observa tions taken on different days averaged about 0.2% and appeared to depend mainly on variations of atmospheric absorption, the correction for which doubled the time and labour of taking obser vations. The percentage absorbed varies to some extent with the quality of the radiation as determined by the temperature of the emitter as well as the state of the atmosphere, and is not simply proportional to the distance traversed as commonly assumed. The observations with the black body at 444.5° C, when corrected by reference to hygrometric records, using the coefficient found at I00° C, were raised from a mean value 5.690 to 5.804, which suggests that the absorption correction should be smaller for radiation at 444.5° C than at 100° C. The mere presence of an observer radiating heat and exhaling variable quantities of CO, is a source of uncertainty in absolute measurements. Apart from atmospheric absorption, the instrument appeared to be capable of an order of accuracy of at least 0.1%. It was accordingly decided to enclose the receiver in a water-cooled metal casting from which absorbing gases could be excluded. Unfortunately at this stage the work was interrupted by the World War, and no favourable opportunity has since occurred for making the final corrections for absorption. It appears, however, that the result would probably be intermediate between those of Gerlach and Coblentz by the Angstrom method. A number of other highly in genious methods have been employed for the absolute determina tion of this important constant, but have generally been inferior to the electric methods in ness and sensitivity, and do not promise so high a degree of racy. Some experienced ers have found values as high as but there are many most insidious sources of error in these difficult experiments.

45. Wien's Displacement Law.—Assuming that the fourth power law gives the quantity of full radiation at any temperature it remains to determine how the quality of the radiation varies with the temperature, since as we have seen both quantity and quality are determinate. This question may be regarded as con sisting of two parts. (I) How is the wave-length or frequency of full or "black" radiation changed when its temperature is altered? (2) What is the form of the curve expressing the distribution of energy between the various wave-lengths in the spectrum of full radiation, or what is the distribution of heat in the spectrum? The researches of Tyndall, Draper, Langley and other investiga tors had shown that while the energy of radiation of each fre quency increased with rise of temperature, the maximum of intensity was shifted or displaced along the spectrum in the direc tion of shorter wave-lengths or higher frequencies. W. Wien (Ann. Phys., 1898), applying Doppler's principle to the adiabatic compression of radiation in a perfectly reflecting enclosure, de duced that the wave-length of each constituent of the radiation should be shortened in proportion to the rise of temperature pro duced by the compression, in such a manner that the product AT of the wave-length and the absolute temperature should remain constant. According to this relation, which is known as Wien's displacement law, the frequency corresponding to the maximum ordinate of the energy curve of the normal spectrum of full radia tion should vary directly (or the wave-length inversely) as the absolute temperature, a result previously obtained by H. F. Weber (1888). Paschen, Lummer and Pringsheim verified this relation by observing with a bolometer the intensity at different points in the spectrum produced by a fluorite prism. The intensi ties were corrected and reduced to a wave-length scale with the aid of Paschen's results on the dispersion formula of fluorite (Wied. Ann., 1894). The curves in fig. 18 illustrate curves ob tained by Lummer and Prings heim (Ber. dent. plays. Ges., 1899) at three different tem peratures, namely 1,377°, 1,087° and 836° absolute, plotted on a wave-length base with a scale of microns µ or millionths of a metre. The wave-lengths Oa, Ob, Oc, corresponding to the maximum ordinates of each curve, vary inversely as the absolute temperatures given. The constant value of the product X T at the maximum point was found to be 2,920. Thus for a temperature of 1,000°A the maximum is at wave-length 2.92µ; at the maximum is at 1.46µ.

46.

Distribution of Energy in the Spectrum.—Assuming Wien's displacement law, it follows that the form of the curve representing the distribution of energy in the spectrum of full radiation should be the same for different temperatures with the maximum displaced in proportion to the absolute temperature, and with the total area increased in proportion to the fourth power of the absolute temperature. Observations taken with a bolometer along the length of a normal or wave-length spectrum, would give the form of the curve plotted on a wave-length base. The height of the ordinate at each point would represent the energy included between given limits of wave-length, depending on the width of the bolometer strip and the slit. Supposing that the bolometer strip had a width corresponding to •orµ, and were placed at 1.0/2 in the spectrum of radiation at 2,000°A, it would receive the energy corresponding to wave-lengths between i •oo and 1•oiµ. At a temperature of i,000°A the corresponding part of the energy, by Wien's displacement law, would lie between the limits 2.00 and 2•o2 p, and the total energy between these limits would be 16 times smaller. But the bolometer strip placed at 2.0/2 would now receive only half of the energy, or the energy in a band •oIµ wide, and the deflection would be 32 times less. Corresponding ordinates of the curves at different temper atures will therefore vary as the fifth power of the temperature, when the curves are plotted on a wave-length base. The maximum ordinates in the curves already given are found to vary as the fifth powers of the corresponding temperatures.The equation representing the distribution of energy on a wave length base must be of the form where F (X T) represents some function of the product of the wave-length and temperature, which remains constant for corre sponding wave-lengths when T is changed. If the curves were plotted on a frequency base, owing to the change of scale, the maximum ordinates would vary as the cube of the temperature instead of the fifth power, but the form of the function F would remain unaltered. Reasoning on the analogy of the distribution of velocities among the particles of a gas on the kinetic theory, which is a very similar problem, Wien was led to assume that the function F should be of the form T, where e is the base of Napierian logarithms, and c is a constant having the value 14,600 if the wave-length is measured in microns . This expression was found by Paschen to give a very good approximation to the form of the curve obtained experimentally for those portions of the visible and infra-red spectrum where observations could be most accurately made. The formula was tested in two ways: (I) by plotting the curves of distribution of energy in the spectrum for constant temperatures as illustrated in fig. 19: (2) by plotting the energy corresponding to a given wave-length as a function of the temperature. Both methods gave very good agreement with Wien's formula for values of the product XT not much exceeding 3,000.

A method of isolating rays of great wave-length by successive reflection was devised by H. Rubens and E. F. Nichols (Wied. Ann., 1897) . They found that quartz and fluorite possessed the property of selective reflection for rays of wave-length 8.8,u and 24,u to 32p, respectively, so that after four to six reflections these rays could be isolated from a source at any temperature in a state of considerable purity. The residual impurity at any stage could be estimated by interposing a thin plate of quartz or fluorite which completely reflected or absorbed the residual rays, but allowed the impurity to pass. H. Beckmann, under the direc tion of Rubens, investigated the variation with temperature of the residual rays reflected from fluorite employing sources from —8o° to 600° C, and found the results could not be represented by Wien's formula unless the constant c were taken as 26,00o in place of 14,600. In their first series of observations extending to 6,u O. R. Lummer and E. Pringsheim (Dent. phys. Ges., 1899) found systematic deviations indicating an increase in the value of the constant c for long waves and high temperatures. In a theoretical discussion of the subject, Lord Rayleigh (Phil. Mag., 1900) pointed out that Wien's law would lead to a limiting value of the radiation corresponding to any particular wave-length when the temperature increased to infinity, whereas according to his view the radiation of great wave-length should ultimately increase in direct proportion to the temperature. Lummer and Pring sheim (Dent. phys. Ges., 1900) extended the range of their obser vations to 18µ by employing a prism of sylvine in place of fluorite. They found deviations from Wien's formula increasing to nearly 50% at 18p, where, however, the observations were very difficult on account of the smallness of the energy to be measured. Rubens and F. Kurlbaum (Ann. Phys., 1901) extended the residual reflection method to a temperature range from —190° to 1,500° C, and employed the rays reflected from quartz 8.8µ, and rocksalt 51A, in addition to those from fluorite.

It appeared from these re searches that the rays of great wave-length from a source at a high temperature tended to vary in the limit directly as the abso lute temperature of the source, as suggested by Lord Rayleigh, and could not be represented by Wien's formula with any value of the constant c. The formula now generally accepted is that proposed by Max Planck (Ann. Phys., Igo') namely, which agrees with Wien's formula when T is small, where Wien's formula is known to be satisfactory, but approaches the limiting form E= when T is large, thus satisfying the condition proposed by Lord Rayleigh. The theoretical interpretation of this formula is discussed in the article RADIATION. The most re cent value of the constant c in Planck's formula is 14,300, as given by Warburg. In order to compare Planck's formula graphically with Wien's, the distribution curves corresponding to both formu lae are plotted in fig. 19 for a temperature of 2000° A, with a scale of wave-length in The curves in fig. 20 illustrate the difference between the two formulae for the variation of the intensity of radiation with tem perature for a fixed wave-length Soµ which is five times as long as the limit 6p of the curves in fig. 20. But at A the energy to be measured at Soµ is about ten thousand times less than at the maximum of the curve in fig. 20. As suming Wien's displacement law, the curves may be applied to find the energy for any other wave-length or temperature, by sim ply altering the wave-length scale in inverse ratio to the temperature, or vice versa. Thus to find the distribution curve for 1,000° A, it is only necessary to multiply all the numbers in the wave-length scale of fig. 19 by 2; or to find the variation curve for wave-length 6o,2 the numbers on the temperature scale of fig. 20 should be di vided by 2. The ordinate scales must be in creased in proportion to the fifth power of the temperature, or inversely as the fifth power of the wave-length respectively in figs. 19 and 20 if com parative results are required for different temperatures or wave lengths.