The Chromosome Theory

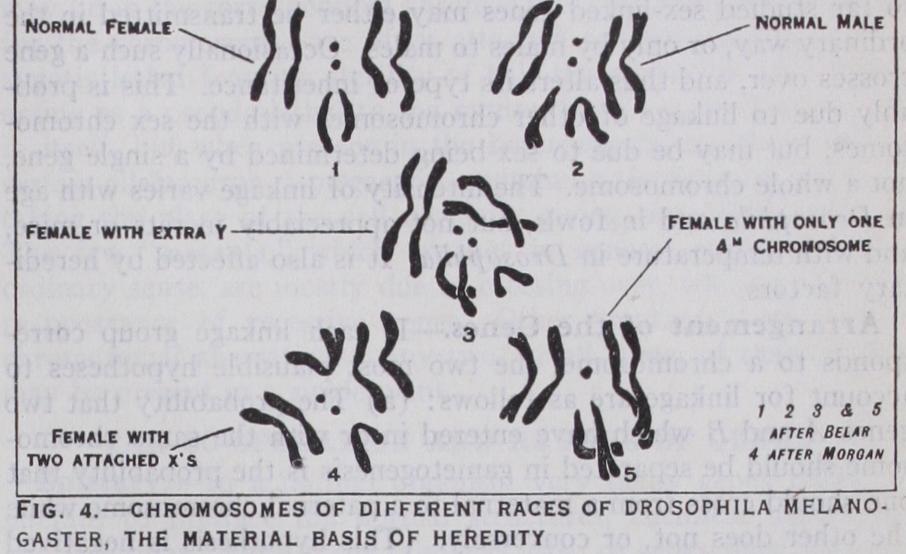

THE CHROMOSOME THEORY Since the sex-linked genes were associated with the X chromo some, it is natural to suggest that the other genes should be simi larly associated with the other chromosomes. If so there should be as many groups of mutually linked genes as there are chromo somes in the gametes. This is the case in Drosophila melanogaster and the sweet pea, the organisms most thoroughly investigated. In the former the number of chromosomes in the gamete, and of linkage groups, is four (fig. 4, I, 2), in the latter seven. In no organism has it been shown that there are more linkage groups than chromosomes, but in some there appear to be fewer.

The evidence that, in Drosophila melanogaster at least, a linked group of genes is carried on or by an individual chromosome, is overwhelming. Thus occasional females are found which have a Y chromosome as well as 2 X's. (fig. r, 3) . These form four types of egg, many containing X and XY and fewer containing XX and Y. If such a female be mated with a male carrying a dominant sex-linked gene (e.g., that for• "Bar" or oblong eye) which with a normal female would give bar-eyed daughters and normal sons, the following types of offspring may be expected, representing the bar-carrying X chromosome by X', so that the spermatozoa carry X' or Y:— From X' spermatozoa: X'X (bar 9) X'XY (bar ), X'XX (dies), X' Y (bar a' ) From Y spermatozoa: X Y (normal d'), XYY (normal a'), XX Y (normal ? ), YY (dies).

There are thus exceptional bar-eyed males and normal females, of which the latter behave genetically like their mothers. Similarly the X'XY and XYY individuals behave according to theoretical expectation.

Again the two X chromosomes in a female may be attached to form a V (fig. I, 4). Such females, as will be seen, also inevitably contain a Y. They therefore form eggs containing XX and Y. With a normal male they produce zygotes : XXX (dies), XX Y ( 9 ) X Y (a') YY (dies).Xxx(dies), XX Y ( 9 ) X Y (a') YY (dies).

Hence the female offspring get two united X chromosomes from their mother, the males get the X from their father. Thus sex-linked genes involved in such a cross are handed down from father to son and from mother to daughter, and not passed from one to the other as in the normal case.

Again Drosophila melanogaster may lose one of its small fourth chromosomes, such flies being viable but small (fig. r, 5). Now of over 400 genes known in this fly one linkage group contains only three, and is therefore thought to be associated with the small chromosome. A recessive character determined by one of these genes is eyelessness. If E is the gene for normal eyes, e for eye lessness, the small unhealthy round-eyed fly with only one small chromosome may be denoted by Eo, the cytologically normal fly heterozygous for eyelessness by Ee. When these are mated the four types of zygote formed are EE (normal), Ee (heterozygote) Eo (small normal) and eo (small eyeless). In a similar way the chromosome containing the recessive gene determining the waltz ing habit has been identified in the mouse, though here only a part of it was missing in the cytologically abnormal individuals. Many other cases are known which enable given genes to be allotted to visibly distinguishable chromosomes. For example in Drosophila melanogaster individuals with three instead of two of the small fourth chromosome behave as expected on the above theory.

Except in the case of sex-linked genes, linkage is generally of about the same intensity in the formation of masculine and femin ine gametes. In the same plant it may be stronger for one pair of genes in the formation of pollen, for another in that of ovules. In animals however it is always slightly more intense in the hetero gametic sex, i.e., the male except in birds and Lepidoptera (linkage has not been thoroughly investigated in these groups, except for sex-linked genes). In mammals the intensity is only slightly greater in the male, but in insects sexual dimorphism is very marked in this respect, linkage being almost complete in the males of Or thoptera, and quite complete in the males of Drosophila and the females of Bornbyx, a fact which makes the determination of linkage groups far easier than in plants or mammals. In the fish so far studied sex-linked genes may either be transmitted in the ordinary way, or only by males to males. Occasionally such a gene crosses over, and thus alters its type of inheritance. This is prob ably due to linkage of other chromosomes with the sex chromo somes, but may be due to sex being determined by a single gene, not a whole chromosome. The intensity of linkage varies with age in Drosophila and in fowls, but not appreciably in rats or mice, and with temperature in Drosophila. It is also affected by heredi tary factors.

Arrangement of the Genes.

If each linkage group corre sponds to a chromosome, the two most plausible hypotheses to account for linkage are as follows : (a) The probability that two genes A and B which have entered in or with the same chromo some should be separated in gametogenesis is the probability that one should cross from a maternal to a paternal chromosome while the other does not, or conversely. (This hypothesis is negatived by the facts shortly to be discussed.) (b) Whole blocks of the chromosomes, with their associated genes, may be exchanged. (This hypothesis agrees with the facts.) The farther apart two genes are situated in or on the chromosome the more likely they are to be separated in gametogenesis. Now consider a zygote in which three dominant genes, A, B, C are borne by one chromo some, their recessive allelomorphs a, b, c by the corresponding chromosome derived from the other parent. The formation of an Abc or an aBC gamete means that the chromosomes have crossed over and exchanged genes at a point between the loci of A and B. Similarly the formation of an ABc or an abC gamete means that crossing over has occurred between the loci of B and C. And AbC or aBc gametes are only formed if both these events occur. Now if the probability of crossing over between A and B is and between those of B and C is that of a double cross over is if the fact that crossing over has occurred between A and B does not influence the probability of a cross-over between B and C. Actually the probability of a double cross-over is always somewhat less than this, presumably on account of a stiffness of the chromosomes, which makes it unlikely that they should bend so much as to cross over at two nearly adjacent points. It follows that if the probability of crossing over between A and B is ro%, between B and C is 5%, the probability of a double cross-over is something less than 1%, whereas if the two genes were not arranged in a line it might have any value up to 35%.By determining cross-over values for a number of linked genes it is possible to construct a map of any chromosome. The unit of distance on the map is the separation giving a possibility of ing-over of i % between genes at this distance. This distance does not correspond to a definite distance in millionths of a centimetre, for there is evidence that crossing over occurs more easily in some parts of a chromosome than others. Such a map for 26 of the most important of the i So sex-linked genes of Drosophila melanogaster is given in fig. 5. If x be the distance on the map between two genes, the probability of crossing over between them is given by y=f (ioox) where y= 'cox when both are small, but can never exceed 1, however large the value of x. Approximately x=•7y—•I51oge(I-2y) but the relation between map distance and cross-over value is slightly different in different parts of the same chromosome, so the function is not perfectly definite. In other words, the over value, expressed as a percentage, is equal to the map distance when both are small, very nearly so up to distances of about 20 units, but at 5o units distance (as determined by adding up the tances between the several loci) the cross-over value is only about 40%, and even at a distance of over ioo units it does not exceed 5o%, though it is very near to this value. Extensive chromosome maps have been made for several species of Drosophila, and in the maize plant and sweet pea, less detailed ones in other species. There is no tendency for genes with like effects to aggregate in the same chromosomes or in the same parts of them. However multiple allelomorphic genes always occur in the same locus. Occasionally a race of Drosophila is found which, when crossed with the normal type, gives little or no crossing over in one chromosome or section of a chromosome. This has been found to be due to a reversal in the order of the genes, which prevents the normal pairing. It is generally supposed that crossing over occurs during diakinesis (see CYTOLOGY) when the chromosomes may be seen twisting round one another.