Types of Harbours

TYPES OF HARBOURS Natural sheltered anchorage in its simplest form is sometimes found under the lee of outlying reefs, sand banks or islands. Where there is good holding ground and the shelter afforded is sufficient to give protection from heavy seas, such an anchorage is termed a Roadstead. Examples are the Downs under the shelter of the Goodwin Sands; Dunkirk road, under the lee of the Braekbank sand; Yarmouth roads and the anchorages in sheltered positions in some wide estuaries such as that of the Thames. Others are found in deep embayments where shelter is afforded from the worst winds by projecting headlands, as in Weymouth and Portland roads. A well-known example of a roadstead protected by an island is that sheltered by the Isle of Wight.

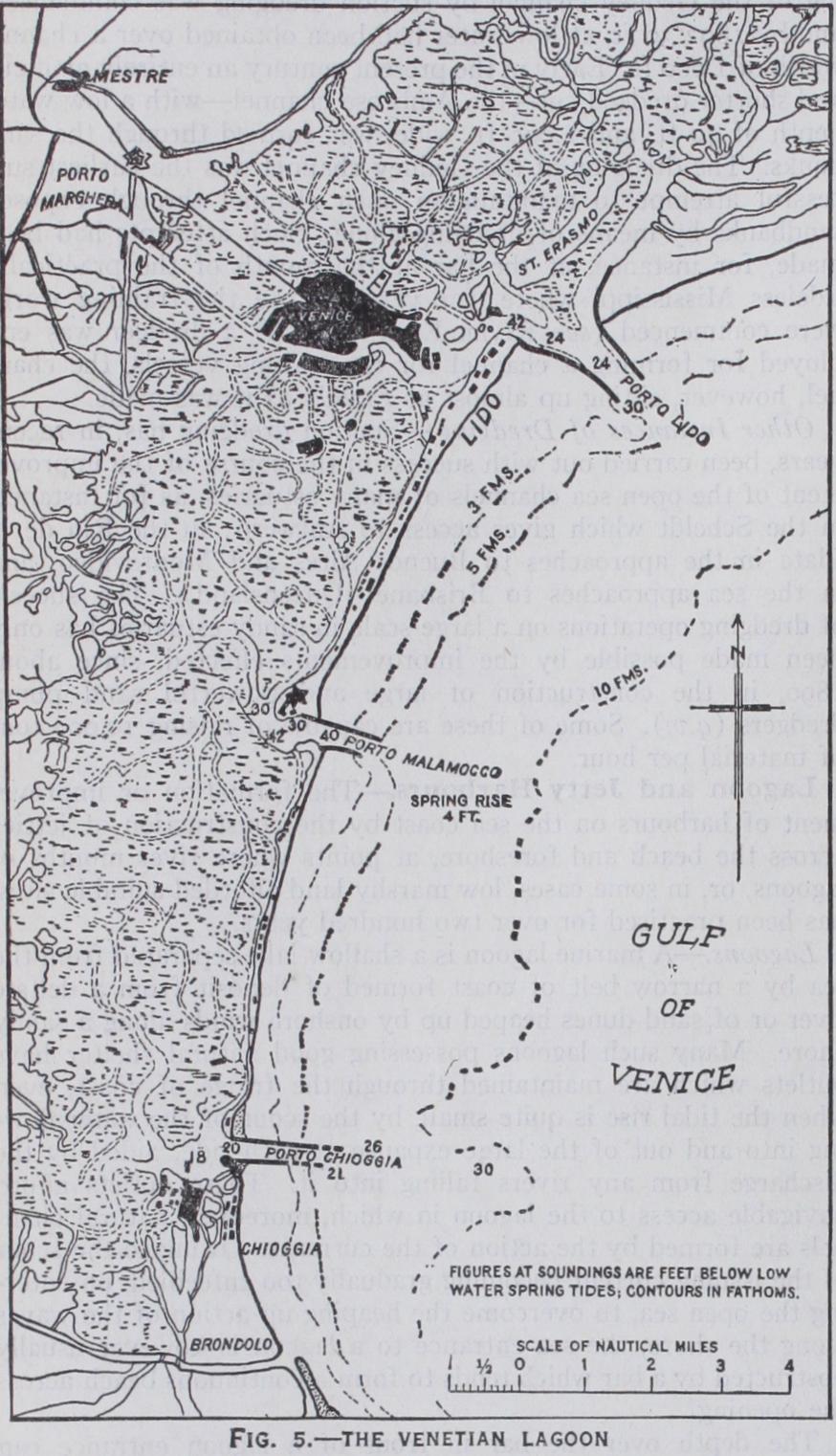

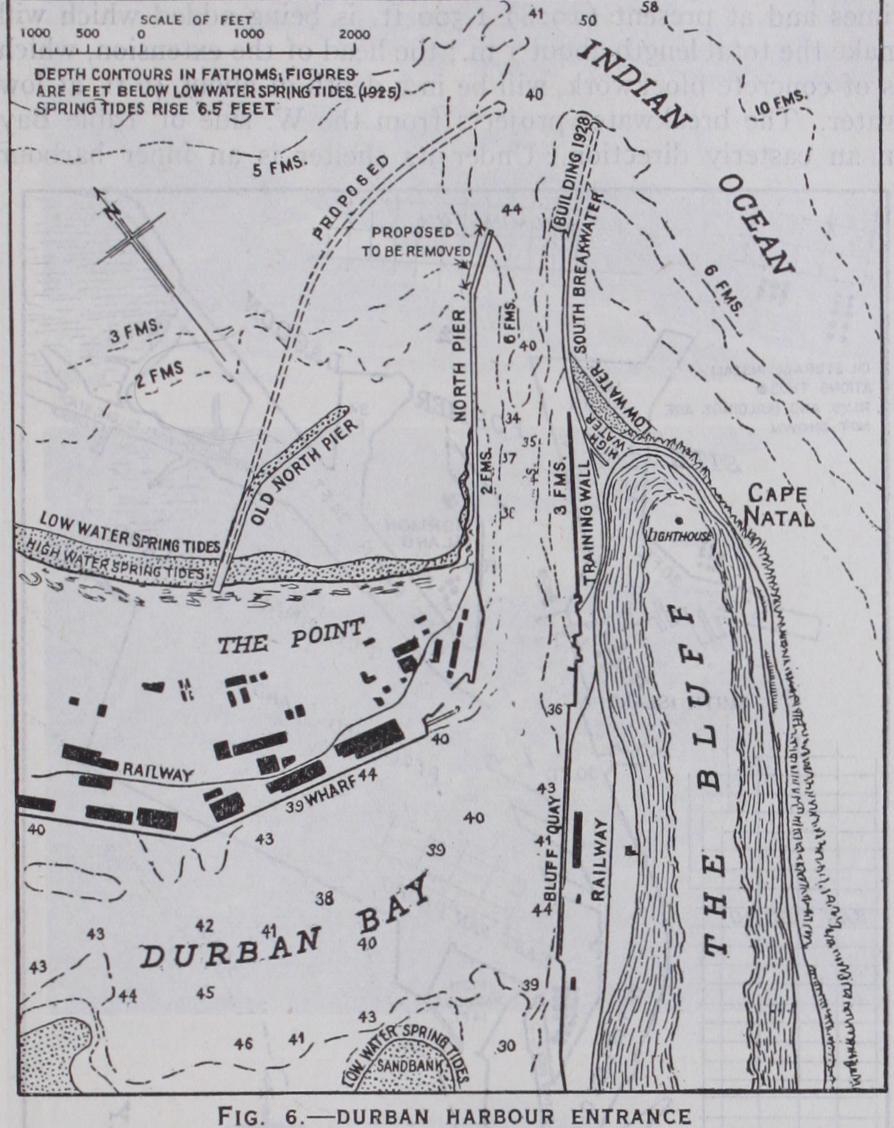

Natural havens to which the term harbour is ordinarily ap plied are those inlets or arms of the sea which are almost com pletely land-locked. Where such natural shelter is found com bined with ample depth of water, both in the approaches and in the anchorage, and in positions convenient for sea-borne trade, it is of great value to shipping; such havens, even without arti ficial works, serve as harbours of refuge, and the necessary interior works of a port can usually be constructed in them without difficulty and at much less cost than in an exposed and open situation. Well-known examples in addition to those already mentioned are the harbours of Port Royal and Kingston in Jamaica, Southampton Water, the land-locked sea inlets of San Francisco, Cromarty Firth, Scapa Flow, Milford Haven, Queens town, Falmouth and Kiel. In many situations, however, there are large enclosed water areas having openings into the sea which are either obstructed by a bar at the entrance, as in the lagoon harbour of Venice and the enclosed bay harbour of Durban, or are shallow. Works of considerable magnitude are often required for the improvement and maintenance of such harbours.

Estuary Harbours and

rivers which pos sess sufficient depth of water in the tidal compartment for the navigation of vessels of considerable draught up to the decks or wharves of the port, are obstructed in the estuary, or where they discharge into the open sea, by banks of sand or silt which, sometimes, are liable to change of position. In other estuaries the approach channels from the open sea to the river proper may be sufficient for all the requirements of shipping while the river channels are of insufficient depth.Not only are such obstructions or "bars" met with in the estuaries of rivers which discharge into seas that are either tide less or of small tidal range, but they are frequently present when the rise and fall of the tide is considerable, as in the Mersey (fig. 3) . Rivers opening out into large expanding estuaries, such as the Severn, Scheldt and Clyde, are usually free from bars ; and rivers which gradually widen out as they approach the sea are not ordinarily impeded by bars, though they may be obstructed by sandbanks, as in the Thames and Humber, through which the tidal streams form good channels to the sea. The formation of a navigable channel through a bar, or the improvement of natural channels to provide for the increased draught of vessels, has been effected in a few cases by dredging alone, in some by training works or jetties, and in many cases by a combination of the two methods. The Mersey at Liverpool and the harbour of New York are notable examples of the first case of estuarine conditions embracing the presence of a bar with deep water in the river above it.

The Mersey Entrance. The inner estuary of the Mersey has a depth in some places of about 63 ft. at low water, but the bar in the principal sea channel of the estuary, in its natural condition up to 1890, had no more than I I ft. depth over it at low water spring tides, and 32 ft. at high water neap tides. The bar is about I I m. seaward of the river entrance between Seaforth and New Brighton. Since 1890 the formation and maintenance of a deeper channel through the bar have been problems of great difficulty and dredging by means of powerful sand-pump dredgers, com menced on an experimental scale in that year, has been carried on almost continuously. The quantity of material removed in recent years from the bar and sea channels averages about 20, 000,000 tons annually. Since 1907 rubble-stone training walls or submerged revetments, brought up to just above low water, have been constructed, first on the concave east side of the Crosby channel and later on its west side, mainly with the object of fixing the channel and preventing its encroachment on the Taylor's bank (fig. 3). In spite of these training works and intensive dredging the minimum depth in the Mersey approach channels has not been increased beyond the 26 ft. at lowest water available in 1907.

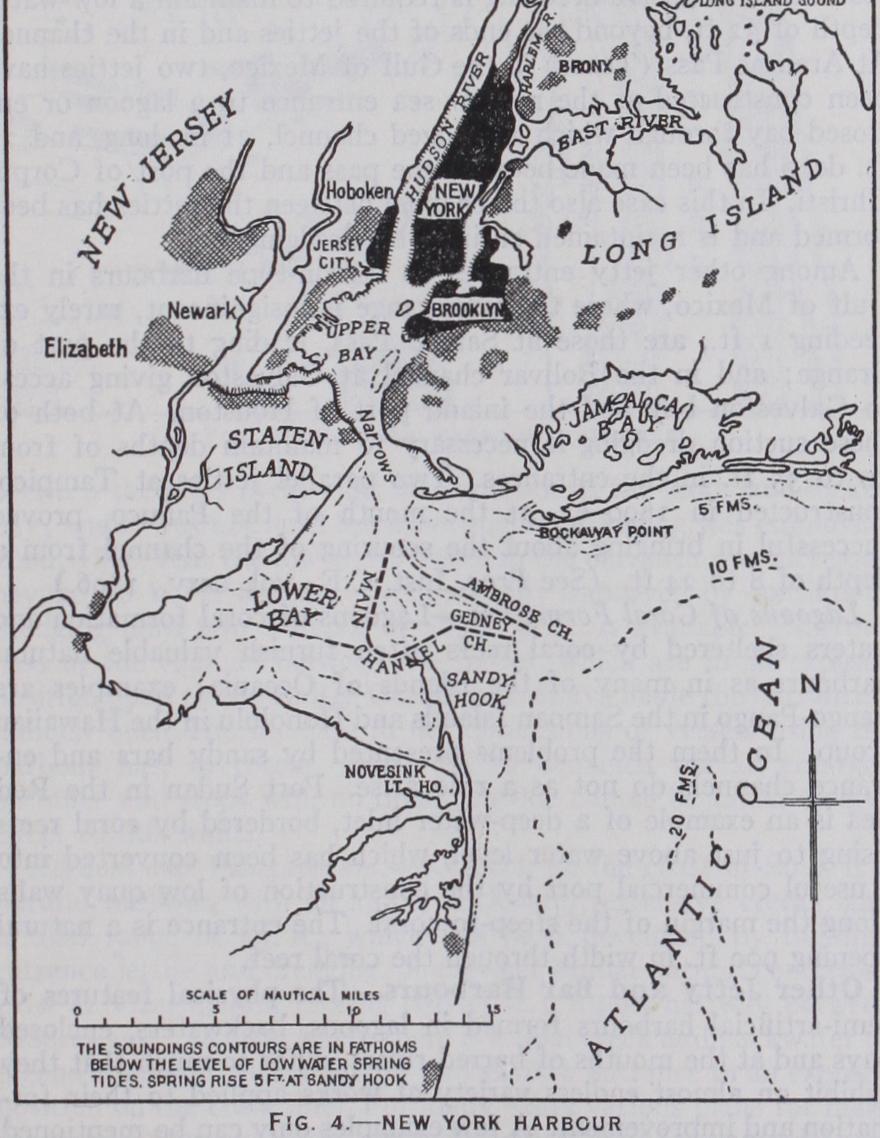

New York Harbour Entrance.—Until 1885 the natural chan nels in the southern approach to New York harbour sufficed for all the requirements of shipping. The Gedney channel had then a depth of about 24 ft. at low water and about 28 ft. at high water neap tides. Above the sandbanks which obstruct the Lower Bay there is ample natural depth—over 44 ft. at low water -up to the principal piers in the harbour (fig. 4). In 1885 the deepen ing of the Gedney channel by suction dredging was commenced, and by 1892 3o ft. at low water had been obtained over a channel width of I,000 ft. Early in the present century an entirely artificial and shorter dredged cut—the Ambrose channel—with a low water depth of 4o ft. and 2,00o ft. wide, was formed through the sand banks. The dredging of the Gedney channel was the earliest suc cessful attempt to maintain an open channel through exposed sandbanks by means of dredging alone. Such attempts had been made, for instance, at the bar at the mouth of the practically tideless Mississippi where, for years before the training works were commenced (see RIVER ENGINEERING) a dredger was em ployed for forming a channel for the waiting vessels, the chan nel, however, silting up almost as rapidly as it was made.

Other Instances of Dredging.—Suction dredging has, in recent years, been carried out with success in the course of the improve ment of the open sea channels of many estuaries, as for instance, in the Scheldt which gives access to Antwerp; in the Rio de la Plata in the approaches to Buenos Aires and Montevideo, and in the sea approaches to Brisbane (Queensland). The success of dredging operations on a large scale in sandy estuaries has only been made possible by the improvements effected, since about 1890, in the construction of large and powerful sand pump dredgers (q.v.). Some of these are capable of raising Io,000 tons of material per hour.

Lagoon and Jetty Harbours.

The formation or improve ment of harbours on the sea coast by the construction of jetties across the beach and foreshore, at points where river mouths or lagoons, or, in some cases, low marshy land afforded suitable sites, has been practised for over two hundred years.Lagoons.—A marine lagoon is a shallow lake separated from the sea by a narrow belt of coast formed of deposit from a deltaic river or of sand dunes heaped up by onshore winds along a sandy shore. Many such lagoons possessing good natural shelter have outlets which are maintained through the fringe of coast, even when the tidal rise is quite small, by the scour of the water flow ing into and out of the large expanse at each tide, aided by the discharge from any rivers falling into it. These outlets afford navigable access to the lagoon in which, moreover, natural chan nels are formed by the action of the currents. Owing to the scour of the issuing current becoming gradually too enfeebled, on enter ing the open sea, to overcome the heaping up action of the waves along the shore, the sea entrance to a lagoon is however usually obstructed by a bar which tends to form a continuous beach across the opening.

The depth over the bar in front of a lagoon entrance can sometimes be improved by concentrating the current through the outlet by jetties on each side. This has been done with success and, up to a point, without recourse to dredging, in the cases of the three entrances to the lagoon harbour of Venice at Malamocco, Lido and Chioggia, where the tidal range at springs is no more than 31 ft. (fig. 5) . At Malamocco the low-water depth on the bar was increased from I II to 31 ft., and at the Lido entrance from 8 to over 22 feet. The two training jetties at Chioggia are not yet completed (1928) but the depth over the bar has already been increased to 20 feet. Since 1921, however, the Lido entrance has been dredged in order to maintain a low-water depth of 24 feet.

Dredging, in combination with the scour induced by jetties constructed since 1909, has provided a deep entrance channel through the bar at Rio Grande do Sul on the south-east coast of Brazil which formerly obstructed the access to a series of deep land-locked lagoons of very large area. On the other hand dredging alone is relied on (1928) to form and maintain a deep channel through the bar which fronts the narrow entrance to a lagoon of great extent and depth at Cochin on the south-west coast of India, and the construction of jetties is not intended.

Jetty Harbours in English Channel,

the sandy shores of the English Channel and North Sea there are several well known harbours where, formerly, flat marshy ground, lying below the level of high water and shut off from the beach by dikes or sand-dunes, was connected with the sea by a small creek or river. In their original condition these ports presented some resemblance, although on a very small scale, to lagoons. Such are the old harbours of Dieppe, Boulogne, Calais, Dunkirk, Nieuport and Ostend. The influx and efflux of the water from these en closed, tide-covered areas, through a narrow opening, sufficed to maintain a shallow channel to the sea across the foreshore, deep enough near high-water for vessels of small draught. When the increase in draught necessitated the provision of an improved channel, the scour of the issuing current was concentrated by erecting jetties across the beach. This obstruction to the littoral drift of sand caused an advance of the low-water line as the jetties were carried seaward so that their further extension was eventually abandoned, as occurred at Dunkirk. Moreover, rec lamation of the low-lying areas was gradually effected, thus reducing the tidal scour. Sluicing basins were therefore formed into which the tide flowed ; the water being shut in at high tide by gates or sluices was released at low water producing a rapid current through the channel. The sluicing current, however, gradually lost its velocity in passing down the channel and was only effective near the basin outlet and down to a moderate depth below low water. The introduction of powerful mechanical dredging appliances and, in particular, the improvement in suc tion dredgers led to the substitution of dredging for artificial sluicing (now seldom resorted to), and made it possible to form and maintain channels of uniform depth within the harbour and also, where necessary, seaward of the jetty heads to deep water.

During the past half century jetty construction has been applied with varying success to the improvement of harbour entrances on a much larger scale than in the Channel ports, not only in Europe but in America and other parts of the world, particularly where a river having a considerable flow or an ex tensive backwater provides the means for effective scour. Instances where scour alone has been effective in securing depths sufficient for large vessels are rare, and dredging has generally to be re sorted to for this purpose. It should be noted here that entrances formed by jetties with a narrow channel between them are, from the point of view of the navigator, unsatisfactory in positions of considerable exposure on the open coast, particularly at ports used by large vessels.

Jetty Harbours in N. America.—In the United States there are many examples of jetty harbours. At Charleston (S.C.), for instance, a land-locked bay 15 sq.m. in extent and with ample depth of water, provides an adequate harbour, but the narrow entrance was obstructed by a bar. Converging entrance jetties, each over 2 m. long, with openings at their inner ends, were constructed to concentrate the scour, due to the tidal range of about 51 ft. at springs, and to protect the channel from littoral drift. The jetties, however, caused an advance of the foreshore and a corresponding progression seaward of the bar with the result that extensive dredging is required to maintain a low-water depth of 32 ft. beyond the ends of the jetties and in the channel. At Aransas Pass (Texas) in the Gulf of Mexico, two jetties have been constructed at the narrow sea entrance to a lagoon or en closed bay through which a dredged channel, 21 m. long, and 25 ft. deep has been made between the pass and the port of Corpus Christi. In this case also the channel between the jetties has been formed and is maintained entirely by dredging.

Among other jetty entrances to lagoon-type harbours in the Gulf of Mexico, where the tidal range is insignificant, rarely ex ceeding I ft., are those at Sabine Pass, leading to the port of Orange ; and in the Bolivar channel at Galveston giving access to Galveston bay and the inland port of Houston. At both of these suction dredging is necessary to maintain depths of from 3o to 35 ft. in the entrances. Two parallel jetties at Tampico, constructed in 189o-92, at the mouth of the Panuco, proved successful in bringing about the scouring of the channel from a depth of 8 to 24 ft. (See Proc. Inst. C.E., vol. cxxv., 1896.) Lagoons of Coral Formation.--Lagoons of coral formation and waters sheltered by coral reefs often furnish valuable natural harbours as in many of the islands of Oceania; examples are Pango-Pango in the Samoan Islands and Honolulu in the Hawaiian group. In them the problems presented by sandy bars and en trance channels do not as a rule arise. Port Sudan in the Red Sea is an example of a deep-water inlet, bordered by coral reefs rising to just above water level, which has been converted into a useful commercial port by the construction of low quay walls along the margin of the steep-to coral. The entrance is a natural opening 90o ft. in width through the coral reef.

Other Jetty and Bar Harbours.

The physical features of semi-artificial harbours formed in lagoons, backwaters, enclosed bays and at the mouths of barred rivers, differ so much that they exhibit an almost endless variety of works applied to their for mation and improvement. A few examples only can be mentioned here.Hook of Holland.—When the artificial channel for the river Maas was cut, during the 'seventies of the last century, from Rotterdam to the North Sea at the Hook, the sea entrance was flanked by diverging jetties. Rapid silting in the entrance led to the construction of a third and internal jetty to contract the channel to a width of 2,100 ft. and thereby increase the scour. Dredging has, however, to be carried on periodically to maintain the low-water depth of 3o ft.

Durban.—The entrance to the land-locked harbour of Durban (see Proc. Inst. C.E., vol. clxvi., 1906; cxciii., 1914; cxcvi., 1914) is between two nearly parallel breakwaters or jetties about 600 ft. apart, though the channel is no more than 40o ft. wide (fig. 6). Before 1883, when the first breakwater was begun, the bar at the entrance often shoaled so much that there was sometimes less than 3 ft. of water over it. The constant travel of littoral drift from south to north across the harbour mouth almost completely neutralized the scour induced by the great volume of water flowing between the piers every tide, into and out of the large land-locked bay; and it was not until intensive suction dredging was employed, about 1896, that the low-water depth in the entrance was increased beyond 16 ft. It has since been steadily improved by continuous dredging until now a depth of about 36 ft. is available. Narrow ness of the channel between the jetties, which are in an exposed position open to the Indian Ocean, has always made the entrance a difficult one. The increase in the dimensions of vessels using the harbour has, in recent years, led to demands for an enlarged entrance and steps will, no doubt, in due course be taken to give effect to this want.

Karachi and Vizagapatam.—Karachi, on the coast of Sind, is a natural harbour, with an ample backwater, extensive creeks, and a tidal range of 82 ft., which has been developed by building entrance jetties and dredging. Somewhat similar natural conditions exist at Vizagapatam (spring rise 44 ft.), a port halfway between Madras and Calcutta, where there is a tidal creek and backwater of lagoon character with a narrow and shallow entrance in an exposed position on the coast line. For many years various plans for mak ing a deep-water harbour, somewhat after the Madras model and seaward of the creek entrance, have been considered. None of them has been adopted ; but deep-water internal port works are being constructed in the backwater and an interesting and bold attempt is being made to form and maintain, by dredging, a channel of 3o ft. at low water through the narrow entrance and into the backwater, protected by a rubble stone jetty on its northern side only. The construction of a second parallel jetty may be found necessary later.

Lagas, the principal port of Southern Nigeria, has an entrance 1,7oo ft. wide, formed by dredging between converging jetties of rubble stone.

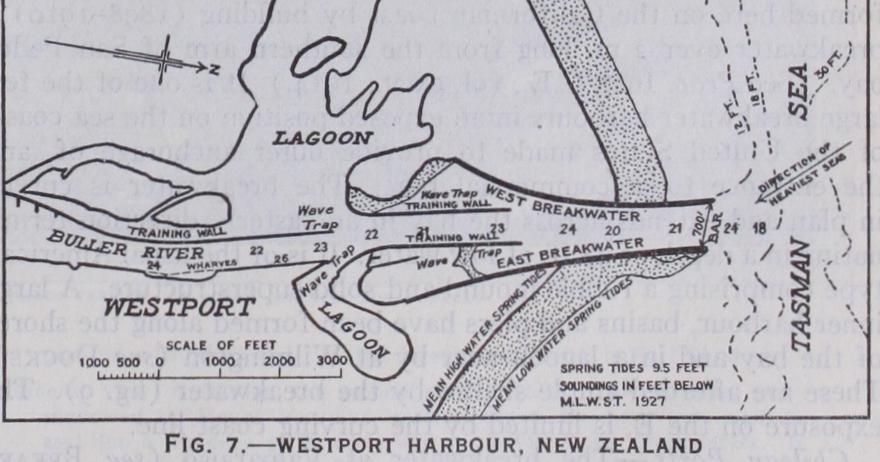

Australian Bar Harbours.—The harbour of Newcastle (N.S.W.), the principal coal port of Australia, is in a backwater into which flows the Hunter river. The entrance was obstructed by a sand bar with less than 13 ft. over it at low water. Jetties con structed to shelter and improve the passage over the bar, where the spring rise is 5 ft., had little effect in the latter direction, but since 1905 dredging has increased the depth to about 26 ft., and a moderate amount of sand dredging suffices to maintain the chan nel depths. The width of channel between the jetties at the entrance, about 1,40o ft., is larger, on account of the exposure, than is usual in jetty harbours. Range in the harbour is consider able and the slight divergence of the jetties tends to increase it. Wavetraps have been formed at the sides of the channel between the jetties.

Fremantle harbour, the principal port of Western Australia, at the mouth of the Swan river, has been made by the removal of a bar of rock and sand which completely blocked the entrance to the river. At the site of this bar and within it there is now a harbour 36 ft. deep at low water protected by jetty breakwaters. The river mouth is sheltered by outlying islands and shoals and the sand travel is not a serious problem.

New Zealand Bar Harbours.—Otago harbour, one of the few New Zealand natural harbours at which improvement works in the entrance have been necessary, is in the South Island. A training mole at the bar entrance, training works in the inner channel and a moderate amount of dredging have been effective in providing a channel with a least depth of 3o ft. at low water where formerly a sandy bar and inner shoals restricted it to about 15 ft. (See Proc. Inst. C.E., vol. cx., 1892; cxxi., 1895; and cc., 1915.) The harbour is a long narrow sea inlet at the head of which, about 11 m. from the entrance, is situated the town of Dunedin.

Westport, on the W. coast of the South Island and the principal coal port of the dominion, furnishes an example of the provision of wave traps (fig. 7) in an entrance between converging training jetties or breakwaters built in 1886-93. The position is one of moderate exposure, the entrance being open to the Pacific. The combined effect of the contracted river and tidal scour and a moderate amount of dredging has increased the low-water depth over the bar from 4 to about 18 ft., the rise of springs being g ft. (See Proc. Inst. C.E., vol. cxii., 1893; cxxxvi., 1899.) For other examples of jetty harbours at river mouths see JETTY and for harbours at river outlets see RIVER ENGINEERING.

Bay Harbours Protected by a Single Breakwater.—The adoption of a deep-water bay for a harbour reduces the necessity for providing artificial shelter and, in most situations, secures a site not exposed to silting, where sheltering works do not inter fere with any littoral drift along the open coast. In favourable situations a deep and narrow bay or inlet may be sheltered by a single breakwater extended out from one shore across the outlet of the bay, having a single entrance between its extremity and the opposite shore. Sometimes—where the exposure is from one direction only approximately parallel with the coast line at the site, and there is some natural shelter in the opposite direction— a single breakwater extending at right angles to the shore, with a bend or curve inwards at its outer end, suffices to afford the neces sary shelter. As examples of this form of harbour construction` may be mentioned Newhaven breakwater, protecting, on the west side, the approach to the river port which is somewhat sheltered from the moderate easterly storms by Beachy Head ; and Table Bay breakwater, which shelters the harbour from the N.W., pro tection on the opposite side being afforded by the wide sweep of the coast-line of Table Bay. Other examples are Holyhead, Fish guard, Brixham, Victoria (B.C.), Los Angeles and Valparaiso and other harbours on the Chilean coast. The Folkestone harbour pier is an example of a single curved breakwater, sheltering the harbour formed on its E. and N. sides, which also has berths on its outer face. These are used by the cross-channel steamships in heavy weather from the E. or N.E., at which times the inner berths are much exposed.

Fishguard.—The harbour here was made by the building (1900 18) of a breakwater across Fishguard bay. The internal shelter has been increased by the subsequent construction of a second breakwater thrown out from the shore in the middle of the bay. The principal object of this addition was, however, to tranquilize the waters in the berths alongside the steamship quays at the head of the harbour.

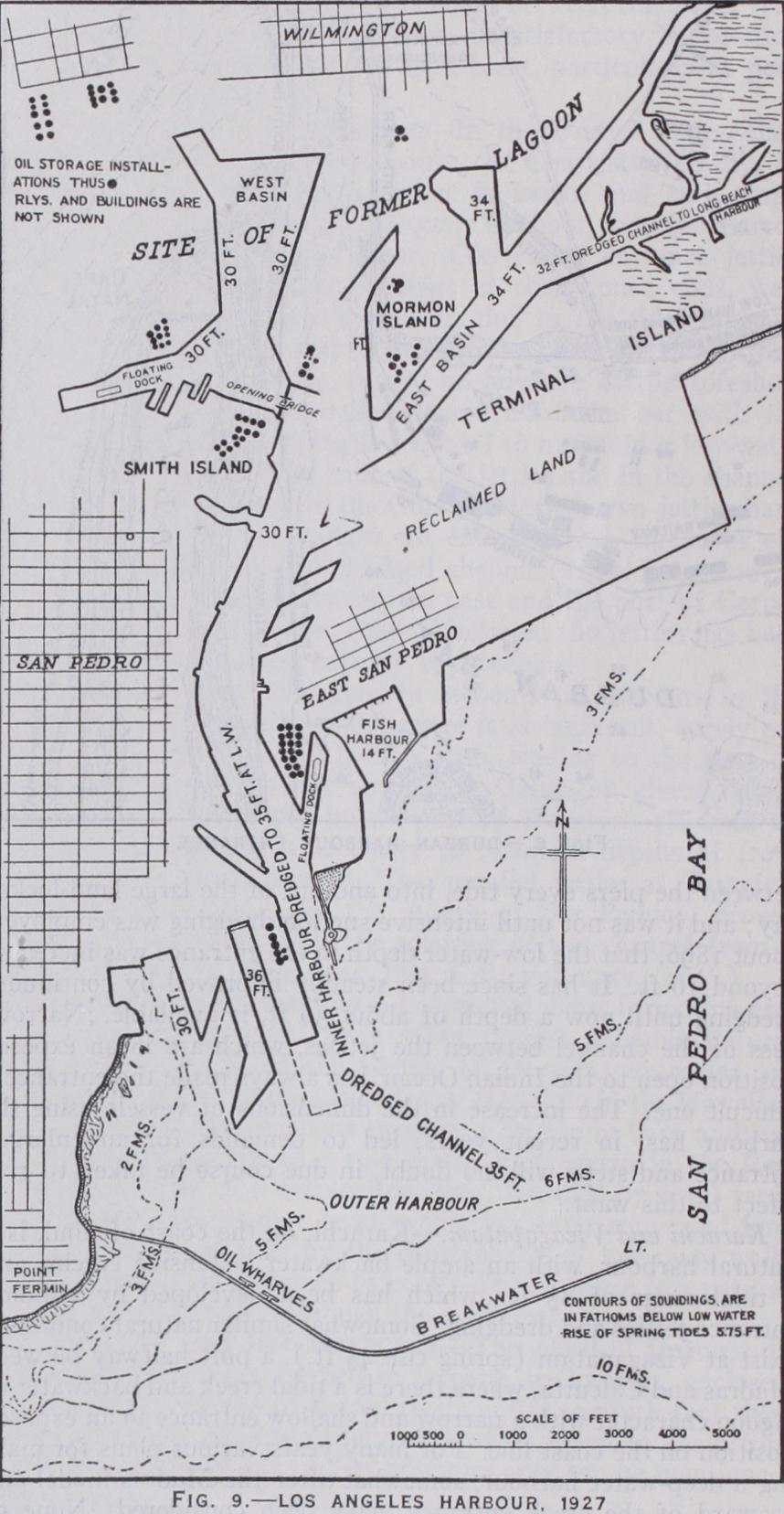

Los Angeles Harbour.—An important artificial harbour has been formed here on the Californian coast by building (1898-191o) a breakwater over 2 m. long from the southern arm of San Pedro bay. (See Proc. Inst. C.E., vol. cxcv., 1914.) It is one of the few large breakwater harbours in an exposed position on the sea coasts of the United States made to provide outer anchorage of, and the entrance to, a commercial port. The breakwater is curved in plan and extends across the bay in an easterly direction termi nating in a depth of 48 ft. at low water. It is of the usual American type comprising a rubble mound and solid superstructure. A large inner harbour, basins and piers have been formed along the shores of the bay and in a lagoon near by at Wilmington (see DocKs). These are afforded ample shelter by the breakwater (fig. 9). The exposure on the E. is limited by the curving coast line.

Chilean Ports.—The breakwater at Valparaiso (see BREAK WATER) is a remarkable structure projecting from the western shore of Valparaiso bay. It will have its termination in a depth of 18o ft. of water. The water area, which will be fully sheltered by the completed breakwater, is small and the cost (reported to be £2,500 per lineal metre for the extension) very large in proportion to the benefit to be derived. (See Proc. Inst. C.E., vol ccxiv., 1923 and xivth., Int. Nay. Congress, Cairo, 1926, Proc. Paper 29 bis.) Single breakwaters have also been built in the bays of San Antonio (1911-18) and Antofagasta (1018-27. In each of these cases the breakwater is bent in plan having two straight arms con nected by a curved portion. The sites are somewhat more sheltered than Valparaiso bay and the depths of water considerably less. At both harbours piers and other inner port works are being con structed under the lee of the breakwater.

Table Bay.—The harbour of Cape Town is generally known by the older name of Table Bay. The present rubble mound break water dates from 186o; it has been extended seaward several times and at present (1928) 1,500 ft. is being added which will make the total length about 1 m. ; the head of the extension, which is of concrete blockwork, will be in a depth of about 46 ft. at low water. The breakwater projects from the W. side of Table Bay in an easterly direction. Under its shelter is an inner harbour having a water area of 75 acres with quays and jetties; and the building of a new and larger inner harbour farther to the S.E. has been commenced.

Island Breakwaters Protecting Embayments.

In the case of a deep, fairly land-locked bay or inlet of the sea, a detached breakwater across the outlet, leaving an entrance between each extremity and the shore, is sometimes sufficient to give the addi tional shelter necessary to form a safe harbour and anchorage. This form of protection is usually only practicable when there is deep enough water near the shore, on one or both sides, to afford suitable entrance.

Plymouth.—The best known example is the breakwater affording the artificial protection necessary to convert the natural harbour of Plymouth into a place of almost perfect shelter. Plymouth Sound, one of the most famous and historic roadsteads of the world, and the deep inlets or creeks above it form a harbour into which fall the rivers Tamar and Plym. The breakwater is 1 m. in length stretching across the middle part of the sound. Begun by John Rennie in i812, it was completed about 1827. In the harbour itself are the naval dockyard establishments at Devonport and Keyham, and small commercial dock and port works at Millbay and in the Cattewater.

Cherbourg.—The breakwater across the wider but shallower bay forming Cherbourg harbour and roadstead is another example of an island structure but in a more open and exposed position than Plymouth. Begun in 1784, its construction was continued under Napoleon, but it was not completed until 1858. Over 24 m. in length it is built, for the most part, in a depth of about 42 ft. at low water. It is of composite construction, a solid superstructure surmounting a rubble stone mound. The sheltered water area is over 2,000 acres in extent, but not more than one quarter of this is of sufficient depth for large vessels. The two entrances on the E. and W. are between the breakwater ends and islands which are themselves joined to the mainland by breakwater walls.

Delaware Bay. The Delaware breakwaters at Cape Henlopen, the S. horn of the entrance to Delaware Bay, are both of the island type. The first, built (1828-69) inshore under the shelter of the headland, is the prototype of American rubble-mound breakwaters. The national harbour of refuge of about Boo acres formed outside the old breakwater by the U.S. Government (1897-1901) is protected by a rubble-mound breakwater 8,04o ft. in length built in a depth at low water of about 3o ft.

Another American island breakwater of the mound type, com menced in 1884 with the object of forming a harbour of refuge in Sandy Bay near Rockport (Mass.), has had a disastrous history of storm damage and the work is still unfinished. The position is one of great exposure for which the rubble-mound type is unsuited.

Island breakwaters frequently form portions of the artificial protection of harbours in conjunction with breakwaters projected from the shore line. Some examples of this combination are referred to hereunder.

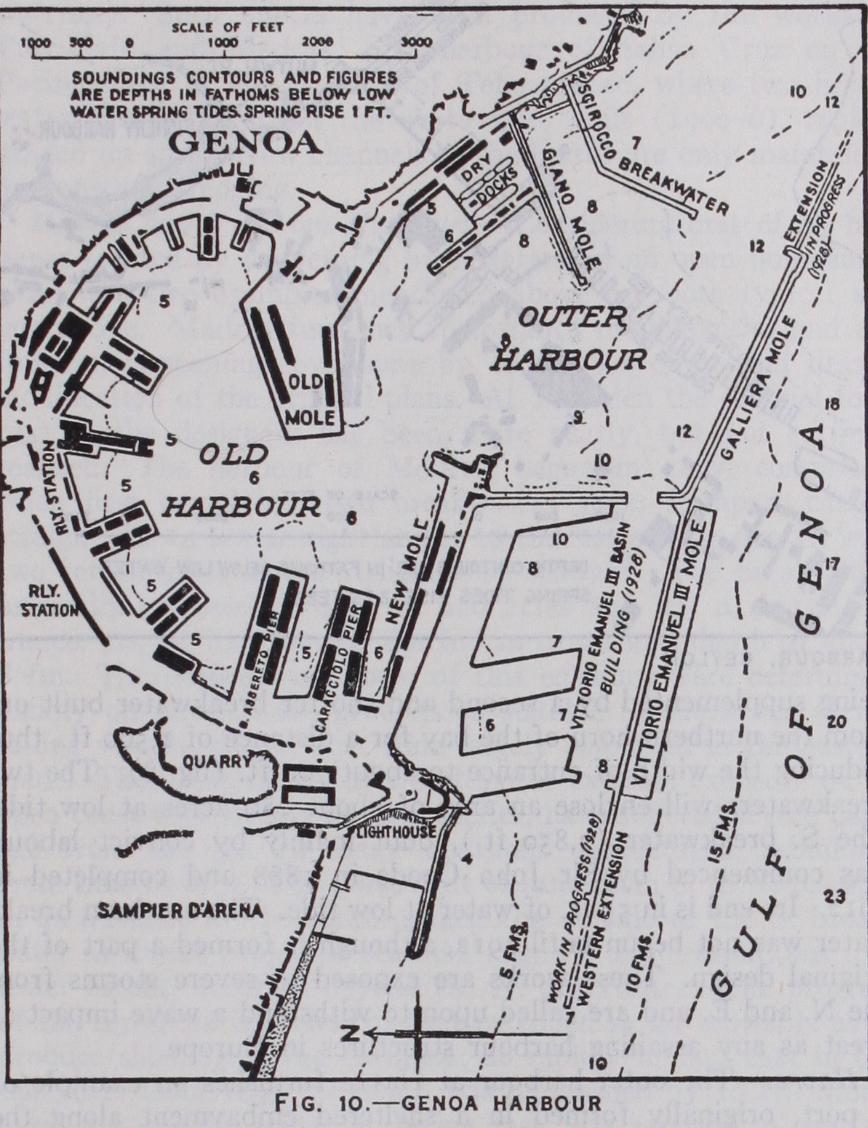

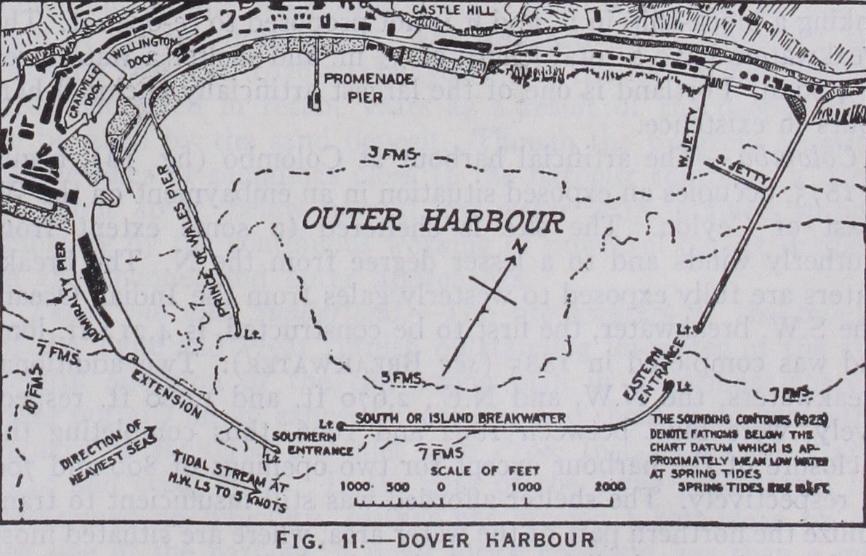

Bay Harbours with Two or More Breakwaters.—The method most generally adopted for the completion of the shelter of deeply indented bay harbours is the construction of a break water extended across the outlet from each shore, leaving a single entrance between their ends, where usually the deepest water is found as at Peterhead and Monaco. If one breakwater placed somewhat farther out is made to overlap an inner one, and so cover it to some extent from the direction of the heaviest seas, a more sheltered entrance is sometimes obtained. This arrangement was adopted when additional protection works were built at the entrance to the old bay harbour at Genoa (fig. io) and for the harbour in Bilbao bay at the mouth of the Nervion. The break waters at Valetta (Malta) and those at the entrance to the almost land-locked Spanish naval harbour at Cartagena are also planned in this way. Many harbours formed in wide or open bays, and in other positions where some abrupt projection from the coast line has been utilized as providing shelter from one quarter, have their protection completed by two or more breakwaters enclosing the site. Dover (fig. i 1) and Colombo (fig. 12) furnish typical and somewhat similar examples. Both of these were begun as single breakwater harbours, and their conversion into enclosed harbours was not completed until many years later.

The extension of artificial shelter has often been brought about not only by the demand for more complete protection against heavy seas and consequent range in a harbour, but also by the growth in the dimensions of ships and the increase in the trade of a port. Thus, greater depth of water and extended accommodation have been obtained at one and the same time with the improve ment of the shelter by building additional breakwaters.

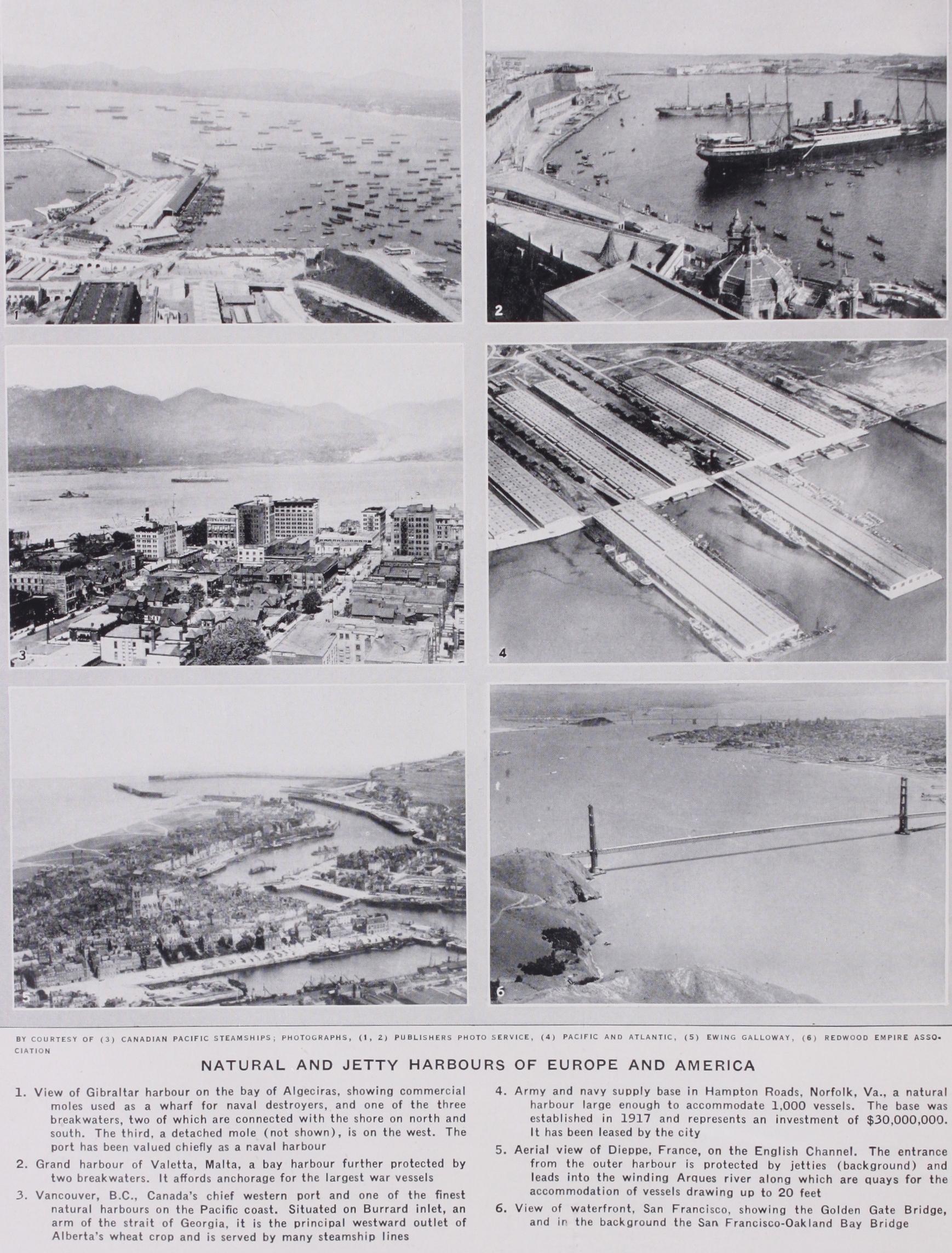

In some instances a wide or exposed entrance to a harbour formed by breakwaters thrown out from the shore has been shel tered by an island breakwater built in front of the opening and thus providing two entrances, one at each end of the island struc ture; Bizerta (Tunis), and Cette furnish examples. In other cases, as at Dover, Portland and Colombo, the line of break waters enclosing the harbour has been made discontinuous, two, and in some cases more, openings being formed between them. The Gibraltar harbour works (1893-1904), made in the sheltered bay of Algeciras on the W. of the Rock, include a detached mole with two entrances between it and the breakwaters which are connected with the shore.

Dover.—This is an example of an artificial harbour formed on a coast of moderate exposure—the narrowest part of the Straits of Dover. The nucleus of the harbour which exists to-day was the Admiralty pier, commenced in 1844 and extended to form the western arm of the outer harbour The pier afforded shelter from the S. and W., and protection from the N. is given by the coast line and was increased later by the building of the Prince of Wales pier. The works carried out between 1897 and 1909 enclose a low-water area of 690 acres and comprise, in addition to the Ad miralty pier, now 4,00o ft. long, an island breakwater of 4,212 ft. and an eastern arm of 2,942 ft. connected with the shore (see BREAKWATER). The harbour was handed over by the Admiralty to the Dover Harbour Board in 1923 for commercial use, and it is now (1928) proposed, with the object of reducing the severe range in the harbour, to close the western entrance (740 ft.), leaving only the eastern opening (650 ft.) available for shipping.

Portland.—The refuge and Admiralty harbour of Portland fur nishes an instance of the conversion of a naturally sheltered road stead into an enclosed harbour by the construction of break waters projecting from the horns of a bay. The Isle of Portland— actually a peninsula joined to the mainland of Dorset by the Chesil Bank—shelters the roads from the S. and the anchorage is exposed to storms only from E. to S. The southern, or inner, and the eastern, or outer, breakwaters were begun in 1849 and completed in 1872, the latter being in 8 to so fm. at low water. Later two additional breakwaters were added, one project ing from the Bincleave rocks near Weymouth on the N. side, and the other, an island structure, on the N.E. of the harbour. The last was finished in 19o4, the building of the later breakwaters being carried out, partly at any rate, as a protection against tor pedo attack. There are three entrances between the four break waters; but one of them, the southern, was closed in 1914 by sinking a block-ship in it, and it is not proposed to re-open it. The breakwaters have a total length of 3-i m. and shelter a water area of 4 sq.m. Portland is one of the largest artificially enclosed har bours in existence.

Colombo.—The artificial harbour at Colombo (fig. 12), begun in 1875, occupies an exposed situation in an embayment on the W. coast of Ceylon. The site is sheltered to some extent from southerly winds and to a lesser degree from the N. The break waters are fully exposed to westerly gales from the Indian Ocean. The S.W. breakwater, the first to be constructed, is 4,212 ft. long and was completed in 1885 (see BREAKWATER). Two additional breakwaters, the N.W. and N.E., 2,67o ft. and 1,o8o ft. respec tively, were built between 1892 and 1906, thus completing the enclosure of the harbour except for two openings of Soo and 700 ft. respectively. The shelter afforded was still insufficient to tran quilize the northern part of the water area, where are situated most of the coaling and oil berths, during the S.W. monsoon. Conse quently a sheltering arm, 1,80o ft. in length, was completed in 1912 as an extension of the original S.W. breakwater. The har bour has a water area of 643 acres at low-water; there is a low water depth of 36 ft. or more, and the harbour has been deepened from time to time to keep pace with the increased draught of vessels. The western entrance has a depth of 4o ft. at low water.

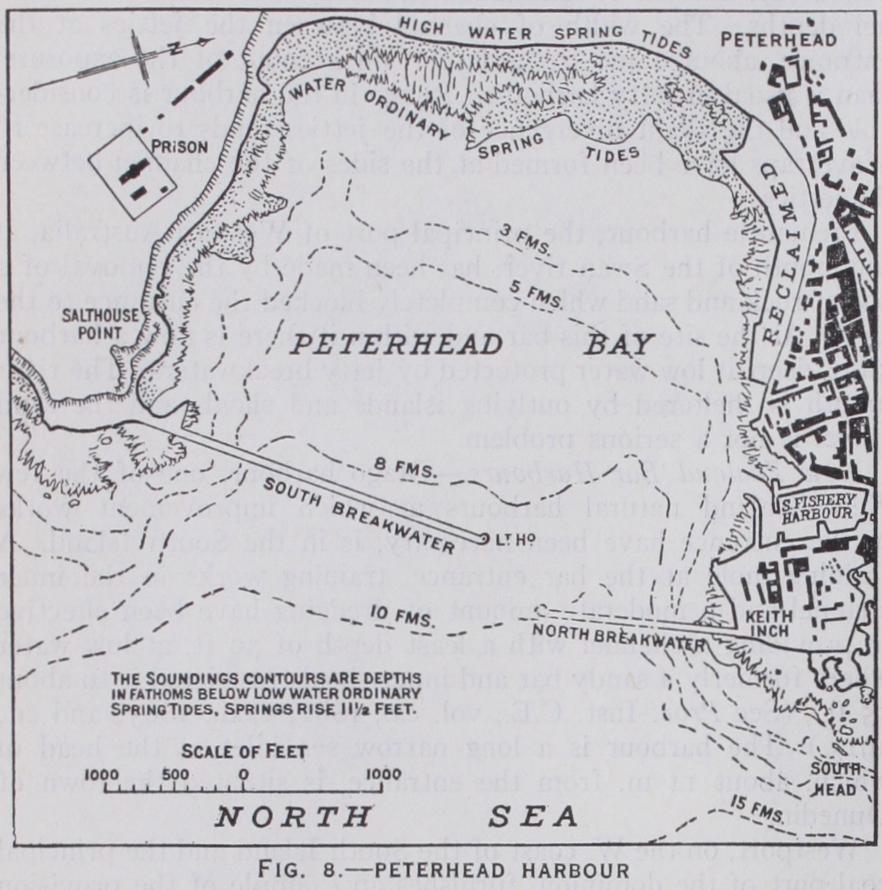

Peterhead.—The shelter afforded by the original single break water of the national harbour of refuge at Peterhead is now (5928) being supplemented by a second and shorter breakwater built out from the northern horn of the bay for a distance of 1,5oo ft., thus reducing the width of entrance to about 700 ft. (fig. 8). The two breakwaters will enclose an area of about 28o acres at low tide. The S. breakwater (2,850 ft.), built mainly by convict labour, was commenced by Sir John Coode in 1888 and completed in Its end is in 55 ft. of water at low tide. The northern break water was not begun until 1912, although it formed a part of the original design. These works are exposed to severe storms from the N. and E. and are called upon to withstand a wave impact as great as any assailing harbour structures in Europe.

Havre.—The outer harbour at Havre furnishes an example of a port, originally formed in a sheltered embayment along the margin of an estuary, where it has been necessary to build long breakwaters extended into more exposed waters, in order to pro vide the additional accommodation demanded by its increasing Lade. The modern deep-water quays in the tidal outer-harbour are situated on areas which have been reclaimed from the sea under the shelter of the breakwater walls.

Artificial Harbours on Open Coasts.

It sometimes happens that harbours have to be constructed where little or no natural shelter exists. When, in such cases, the only possible site is an open sandy shore, considerable littoral drift may occur. Break waters, carried out from the shore at some distance apart, and converging to a central entrance of suitable width, provide the requisite shelter. Such works may be necessary, not only on open unindented coasts, but also to afford increased shelter at a river mouth on an unprotected coast line. Harbours of this descrip tion have, for instance, been made at Madras and Ymuiden on open shores; whilst the breakwaters at the mouth of the Tyne, and those at Sunderland, furnish examples of the protection of river entrances.If there is little littoral drift from the most exposed quarter, the amount of sand brought into the harbour during storms can be readily removed by dredging. The quantity is, moreover, smaller in proportion to the depth into which the entrance is car ried; and the scour across the projecting ends of the break waters tends, in some cases, to keep the outlet free from deposit. If a river discharges into the harbour the detritus and matter in suspension brought down by it must also be taken into considera tion.

Where there is littoral drift in both directions on an open sandy coast, due to winds blowing alternately from opposite quarters, sand accumulates in the sheltered angles outside the harbour on both sides at the junction of the breakwater with the shore line.

This has occurred at Ymuiden. Silting also frequently occurs just inside the breakwater heads under the shelter of the arms. The worst results occur when the littoral drift is mainly in one direc tion, so that the projection of a solid breakwater out from the shore causes a very large accretion on the side facing the exposed quarter, whilst, owing to the arrest of the travel of sand, erosion of the beach occurs beyond the lee breakwater (see COAST PRO TECTION). Such effects have been produced by the works at Port Said and Madras. The harbour of Salina Cruz on the Pacific coast of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, where two break waters projecting from the shore were built (1900-6), rapidly sanded up and narrow channels to the berths are only maintained by constant dredging.

Madras and Ymuiden Harbours.—Considering first of all har bours formed by converging breakwaters on an open unindented coast, the two examples mentioned above are both typical and instructive. Madras furnishes an instance of difficulties and un foreseen happenings overcome by continuous effort and drastic modification of the original plans. At Ymuiden the original fore cast of the designers has been more nearly, but not entirely, realized. The harbour of Madras, begun in 1877, comprised, when first completed, two breakwaters 3,00o ft. apart, carried straight out to sea at right angles to the shore for 3,00o ft. with two return arms inclined slightly to seaward. The breakwaters originally enclosed an area of 220 acres and left a central en trance, 515 ft. wide, facing the Indian ocean in a depth of about 8 fm. The position and form of this entrance were determined mainly on navigational grounds as suitable to the needs of the sailing vessels, still at that time largely employed in the eastern trade. The breakwaters, in a position of extreme exposure on an open coast without any natural shelter, have suffered severe dam age from the sea on many occasions necessitating rebuilding from time to time. The great drift of sand from S. to N. resulted in an advance of the shore against the outside of the S. break water as it was projected seaward (fig. 2), and erosion, but to a lesser extent, occurred beyond the N. breakwater. The progress of the foreshore in course of time extended so far seawards as to produce shoaling at the entrance ; so rapidly in fact that in the ten years from 1893 the depth was diminished by io ft. More over, the original entrance, facing east, was exposed to the full force of waves during both the N.E. and the S.W. monsoons. At these seasons the range within the harbour was severe and at times vessels could not ride at moorings in safety. A new en trance was therefore constructed by forming an opening in the breakwater on the N. side of the harbour, protected by a shelter ing arm, the original eastern entrance being closed when the new entrance had been made (1906-11). The harbour is now com paratively tranquil and vessels are able at all times to lie at the quays in safety.

The advance of the shore line seawards on the S. side of the harbour still appears to average over 25 ft. a year, but the rate of progression tends to decrease as the sand deposit extends into deeper water. The drift of sand along the outside face of the eastern breakwater wall has been checked, at any rate temporarily, by the construction of an extension seaward of the S. breakwater 700 ft. in length which was begun in 1924. This spur breakwater or groyne is protected by concrete blocks placed pell mell on each side. Incidentally the accretion of sand on the S. side of the harbour is not an unmixed evil for the value of the land so formed is increasing with the expansion of the city and much of it has been sold for over £3,000 per acre. Since the tranquilizing of the water area in 1911, the quay accommodation has been largely increased (see Proc. Inst. C.E., Passim).

The harbour at Ymuiden, constructed during the 'seventies of the last century, is an entirely artificial one formed, on the open sandy shore and bed of the North Sea, to serve as the entrance to the Amsterdam ship canal. The breakwaters, each about a mile in length, are converging and the entrance faces W. A dredged channel extends from deep water outside the break waters to the canal locks. This channel is (1928) being deepened to 4o ft. below mean sea level (spring rise, 51 ft.). The actual entrance to the canal channel is between parallel jetties built on the original foreshore where the cut through the sand dunes was first made. The entrance between the breakwater heads is about Soo ft. in width, the harbour widening to 3,80o ft. at the shore line, thus providing broad expending beaches on either side of the canal entrance. The construction of the large entrance lock (see CANALS AND CANALIZED RIVERS) necessitated the sacrifice of a part of the northern spending beach to the formation of an additional and wider canal entrance. In order to compensate for this loss the inner portion of the N. breakwater is being recon structed so as to form a large wave trap on the N. side of the new channel jetties. The advance of the shore on both sides of the harbour at Ymuiden appears to have reached its limit only a short distance out from the old shore line on each side. The only evidence of drift consists in the advance seawards of the line of soundings alongside, and in the considerable amount of sand which enters the harbour and has to be removed by bucket dredging. For dredging outside the breakwaters suction dredgers are employed. A condition of balance has now been reached. Dredging operations, fairly uniform and continuous in amount (about 1,700,000 c.yd. per annum), but not economically burden some in proportion to the commercial importance of the harbour, serve to maintain the required depths of water. It is interesting to note here that an early instance of the employment of sand pump dredgers was in connection with the construction of the harbour by British engineers about 1874 (see Proc. Inst. C.E., vol. lxii., 1880).

Port Said Harbour, at the Mediterranean entrance of the Suez canal, is interesting as an example of the successful formation of an artificial harbour on an open shore where the littoral drift is almost wholly in one direction. The exposure is moderate and the sea bed slopes very slowly towards deep water. Owing to the prevalence of N.W. winds, the drift is from W. to E., and is aug mented by the alluvium issuing from the Nile. The original har bour was formed by two converging breakwaters or jetties, of which the western has been extended seaward from time to time as successive deepenings of the canal were effected. Its total length in 1927 was 6,565 yd. and its termination in a depth of water of 38 ft. (see E. Quellennec, Breakwaters of Egyptian Har bours, Paper 31 bis., and P. Solente, Paper 54 ; xiv. Int. Con gress of Navigation, Cairo, 1926). The outer portion is a sub merged mound serving merely to prevent sand and silt from en tering the dredged channel except around the seaward extremity; a further extension was being made in 1928. The E. breakwater, on the less exposed side, is 2,625 yd. long (fig. 13) . The shore has advanced considerably against the outer face of the W. break water and at the same time erosion has taken place on the E. side of the E. breakwater. The advance on the western side between 1858 and 1926 was 2,75o ft., but the rate of progress has been decreased in recent years as a result of the deeper water to be filled by the sand deposit. Though the progress seawards of the lines of soundings close to the harbour continues a depth of about 4o ft. below normal low water is maintained without difficulty by the continuous working of powerful bucket dredgers in the channel and outer approaches.

The Tyne and Sunderland.—The breakwaters at the mouths of the Tyne and Wear furnish outstanding instances of the suc cessful adoption of the converging plan in situations where a river outfalls on an exposed coast line and there is no protecting estuary or sheltered sea inlet (see Proc. Inst. C.E., vol. clxxv., 1910 and cclx., 1921). In the case of the Tyne sand travel has occasioned no difficulty, neither has erosion taken place on the lee side of the harbour, a small rocky headland less than a mile S. forming a natural groyne which has trapped sand and shingle in the embayment between it and the S. pier. At Sunderland some accumulation, though not to a serious extent, has occurred on the N. side of the harbour works and erosion of the foreshore to the S. has necessitated the carrying out of costly protection works. The building of the Tyne breakwaters (fig. 1) was com menced in 1855; they were originally designed to terminate in a depth of I 5 ft. at low water, but when more than half finished it was decided to extend them seaward to near the 6 fathom contour. This involved changes in the plan of the harbour and accounts for the somewhat peculiar curved form of the S. pier. The N. pier was originally completed in a similar manner but the outer portion was partially destroyed (1895-6) and subsequently re built on a straight line (see BREAKWATER).

The formation of the outer harbour at Tynemouth has provided a safe deep-water approach to the river whose mouth was, about the middle of the last century, obstructed by a sand bar with no more than 5 ft. depth at low water and was, moreover, notorious on account of the difficulty of entrance and the frequency of wrecks. The channel from the harbour to the docks is dredged to 30 ft. at low water spring tides (see RIVER ENGINEERING).

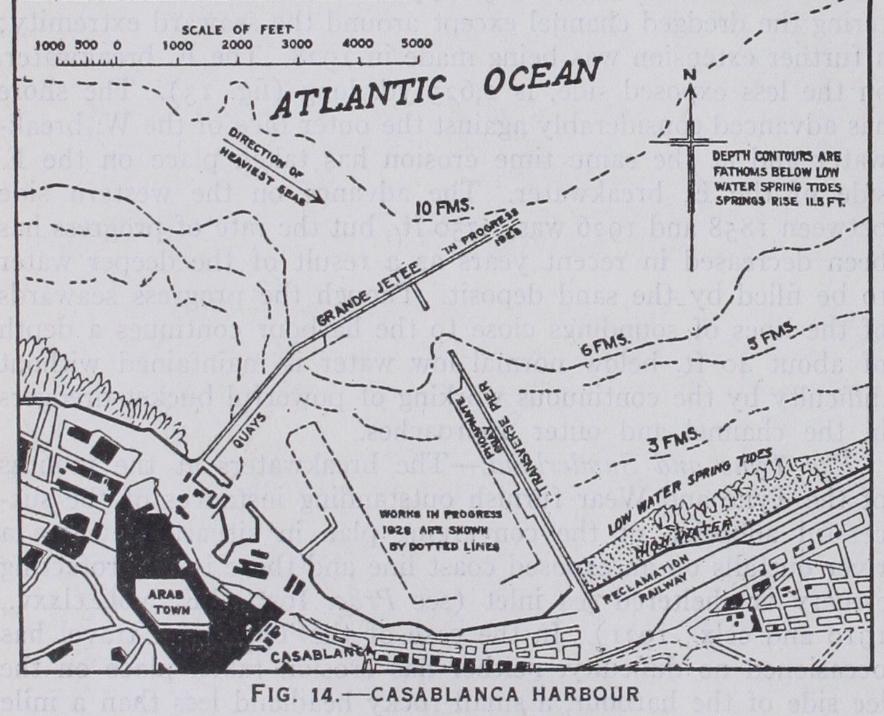

Casablanca.—A recent example of harbour construction carried out on a large scale on an exposed shore is the making of this arti ficial port on the Atlantic, the largest and most important har bour in French Morocco (fig. 14). The construction of a small inshore harbour and jetty was commenced in 1907; the sheltering harbour enclosing about 35o acres, for the most part having a depth of 3o ft. or more at L.W., was begun in 1913, and the main works completed in 1927. The N. and more exposed break water is now (1928) being extended to a total length of 7,215 ft. The works are fully exposed to the Atlantic swell and there is little natural protection, but extensive and well equipped quays are provided alongside the transverse breakwater.

Takoradi.—The artificial deep water harbour of Takoradi, on the Gold Coast (constructed 1921-28), affords an instance of advantage being taken of a rocky reef extending out from the shore to form the foundation for a large part of the main pro tecting breakwater, which is of the rubble mound type. The plan of the harbour is in some ways similar to that of Casablanca, the main breakwater affording shelter on the side exposed to the pre vailing winds and heaviest seas, while a transverse breakwater built under its lee has wharves constructed along its side, and the deep water entrance between the breakwater heads is well shel tered. The site selected for the harbour is on an open coast, but is free from the trouble of littoral drift.

Boulogne.—The old harbour of Boulogne is of the conventional jetty type common to the French and Belgian ports of the Eng lish Channel and North Sea. The formation of a large outer har bour sheltered by breakwaters projected from the shore was com menced as far back as the 'eighties of the last century. The S. or Carnot breakwater has now been built to a length of about 8,30o ft. but the N. breakwater has not yet been begun. When completed, the enclosed low-water area will be over sq.m. and the entrance will be in 36 ft. depth at low-water. The Carnot breakwater is F shaped in plan; its shore end is over 6,000 ft. S. of the jetty entrance to the inner harbour, the intervening foreshore forming an ample expending beach. Boulogne harbour is not free from the troubles arising from littoral drift. The sand travel along the shore from south to north has already led to con siderable accretion along the outer face of the Carnot breakwater and the depth contours are being gradually pushed seaward.

Breakwaters Connected with the Shore by an Open Viaduct.—Proposals have been brought forward from time to time to evade the advance of the foreshore against a solid obstacle by extending an open viaduct across the zone of littoral drift inshore, and forming a closed harbour, or a sheltering breakwater against which vessels can lie, farther seaward and beyond the influence of accretion. It should, however, be pointed out that the single curved arm breakwater can afford adequate protection only in situations of moderate exposure and where the harbour is naturally sheltered on its open side.

Zeebrugge Harbour.—This principle was carried out on a fairly large scale at the port of call formed by the sheltering breakwater constructed (I 9oo-9) in front of the entrance to the Bruges ship canal at Zeebrugge on the sandy North Sea coast. A solid break water, provided with a wide quay furnished with sidings and sheds, and curving round towards the E. so as to overlap the entrance to the canal and shelter an ample water-area, is approached by an open steel and iron viaduct extending out 1,00o ft. from low water into a depth of 20 ft. The solid breakwater is carried out into a depth of 33 f t. at L.W. near the head. It was hoped that by thus avoiding interference with the littoral drift close to the shore, coming mainly, from the W., the accumulation of silt and sand to the W. of the harbour, and also in the harbour itself, would be prevented, or at any rate reduced to a very moderate amount. These hopes have not, however, been realized, and con siderable dredging is necessary in the harbour and at the entrance to the canal in order to maintain the required depths. The prob able explanation of the failure to avoid the troubles of sand accretion and silting is, in this as in other similar cases where the accretion has been still more serious, that the shelter caused by anything in the nature of an island near the shore must result in interference with the natural littoral current and drift and con sequent stoppage of the travelling material.

Ceara and Rosslare.—A plan somewhat similar to that adopted later at Zeebrugge was carried into effect at Ceara on the N.E. coast of Brazil about 1886. Sand accumulated very rapidly, both inside and outside the harbour; in a few years the low water line had receded as far as the breakwater head and the harbour was ultimately abandoned (see Proc. Inst. C.E., vol. clvi., 1904)• Rosslare harbour, near Wexford, on the S.E. coast of Ire land, is another and more favourable example of this type of con struction. Here also, however, dredging has to be carried on periodically to maintain the requisite depths for the safe passage of vessels.

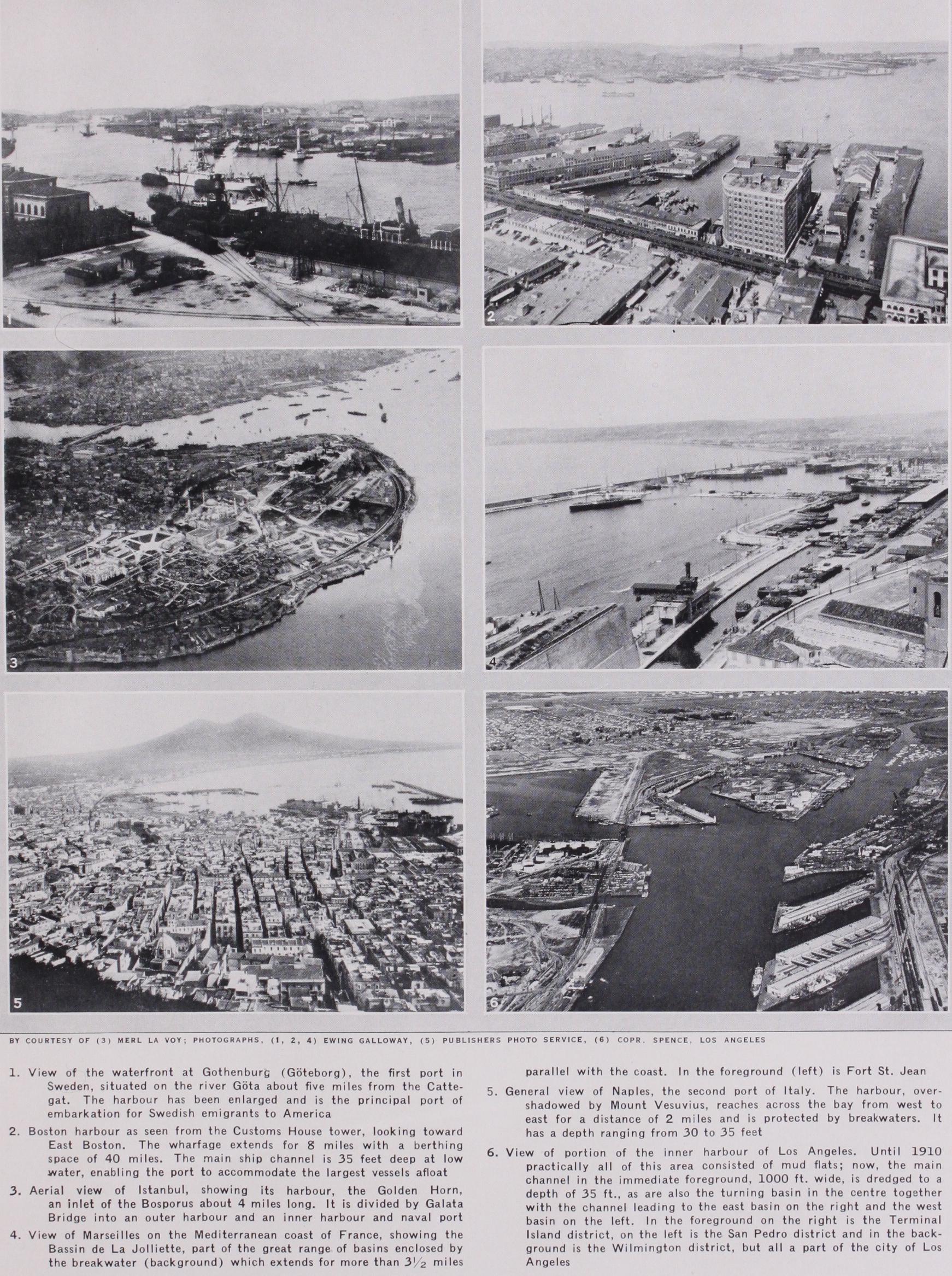

Port Elizabeth.—The protected harbour which, after years of preliminary discussion, is now being made in the waters of the wide Algoa bay at Port Elizabeth, will eventually enclose about 68o acres between two curved breakwaters. The eastern or outer arm was begun in 1922 and will afford shelter from S.E. and E. winds and the heavy seas from that quarter. It starts from the head of the Dom Pedro jetty, a steel openwork structure, 1,40o ft. long, dating from the period of the second Boer war, in about 25 ft. at low-water and will terminate in a depth of about 45 ft. This plan has been adopted with the object of leaving open the space covered by the jetty to allow the current to sweep through and in the hope that this will prevent the sand from silting the harbour or accumulating outside as has happened at Madras. The outer breakwater will be, when completed, about i 4 m. in length, and is being built of sloping blocks of stone. The building of the north arm, 8,000 ft. long (not begun in 193o) will form an enclosed harbour within which reclamations of land and construc tion of jetties are proposed. (See BREAKWATER.) Harbours Sheltered by Works Parallel to Coast.—Many important modern harbours of artificial construction in the Med iterranean and other tideless seas have been formed by building sheltering breakwaters in deep water at some distance from the shore and more or less parallel with it, leaving openings at one or both ends, or at intervals. Under the shelter of these breakwaters inner port works have been constructed (see DocKs). This char acteristic of Mediterranean harbours is due, first of all, to the absence of good river harbours; for in tideless seas the rivers are usually barred by deltas at their outlets, as the Rhone and Tiber. Secondly, many ancient ports were formed in narrow sheltered sea-inlets as, for instance, the old harbour of Marseilles; or in small bays as at Genoa, Naples and Trieste. In course of time the maritime commerce of such ports outgrew the limited re sources of the old harbours and it became necessary to provide enlarged accommodation near by and in deeper water. The only sites available for such extensions have usually been in more open and exposed situations in deep water fronting the adjacent coast line. Moreover, the great depths of water near the shore at many Mediterranean ports, as for example, Marseille and Naples, make lateral extensions more economical and practically convenient than seaward enlargements.

Marseille.—The great breakwater at Marseille (see DocKs) has a total length of more than 31 m. along the shore (fig. 15), and the range of basins enclosed by it is still being extended both N. and S.

Genoa, the greatest port of Italy, was a centre of maritime trade long before the days of Columbus, whose statue overlooks the harbour and who was a native of the city. The old harbour is in a semi-circular bay less than 4 m. in width at its entrance. Around its shores moles and jetties were built from time to time, first in sheltered positions and later in more exposed parts of the bay open to the S. ; still later protection moles were thrown out from the two horns of the bay, and the continued expansion of the port has necessitated the construction of an island break water—the Galliera mole—(begun in 1877 and still being ex tended) stretching E. and W. in front of the old harbour at a distance of over m. from the shore (fig. 1o), and built in water from 5o to 8o ft. deep. Under its shelter port works have been constructed which are further sheltered by subsidiary moles pro jected more or less at right angles to the shore.

Trieste.—The Adriatic port of Trieste furnishes another exam ple of lateral expansion. The old port, situated in a small shel tered bay, called the Doganale Basin, is now used mainly for coastwise shipping. Along the coast to the northward and again to the southward across the entrance to the Bay of Muggia, several island breakwaters, having an aggregate length of over 2 m., have been built to shelter the port works which stretch along the coast line.

Naples.—The old harbour of Naples was formed by building small moles or breakwaters in sheltered positions on the western side of the bay. The San Vincenzo breakwater, which is the nucleus of the modern harbour, was begun in 1836. The harbour now reaches across the wide bay from west to east for a distance of over 2 m. and is protected by a series of breakwaters parallel with the shore. Practically the whole of the modern harbour, having a sheltered area of about I sq. m., is in deep water and little dredging has been required except alongside some of the quays.

Lateral Breakwaters in Sheltered Positions.--In

large land-locked natural harbours and arms of the sea lateral break waters parallel with the shore form convenient and effective means of providing shelter from the short wind waves which are gener ated in them and protection from so much of the ocean swell as may be propagated into the enclosed water area. Behind the shelter of such works, wharves and other port works can be con ; structed where vessels may berth without risk of damage. In this manner the naval and commercial harbours in the land-locked Rade at Brest are protected by island breakwaters fronting them. Another example is the harbour of Kobe, situated in a sheltered part of the inland sea of Japan, where wide, solid and well equipped piers, projecting i,000 to 1,500 ft. from the shore, have been afforded additional protection by the construction of a series of island breakwaters generally parallel with the shore in depths of 35 to 45 ft. These works are still in course of construction (1928).Many of the ports on the shores of the Great Lakes of North America also furnish examples of lateral breakwater protection as, for instance, Chicago, Buffalo, Port Arthur and Toronto. American lake breakwaters are commonly formed of rubble stone mounds or of timber cribwork filled with stone (see BREAK WATER). Breakwaters made in comparatively sheltered positions such as these are naturally of less massive construction than those required in situations exposed to the full force of ocean waves.

Entrances.

Seamen always wish for a wide entrance to a harbour as giving greater facility for safe access; on the other hand, it is important to keep the width as narrow as practicable consistent with easy access, to exclude waves and swell as much as possible and secure tranquillity inside. The result of this conflict is often a compromise. Examples which illustrate the divergence of practice in the dimensions of entrances to artificial harbours have already been mentioned; these differences are mainly due to the equally wide variations in circumstances and exposure, and no generally applicable rule or guiding principle can be formulated, though some authorities maintain that the space between break water heads should never be less than the over-all length of the largest vessel expected to enter the port. The advantages which can sometimes be secured by overlapping breakwaters, covering island breakwaters and double entrances, have already been men tioned; on one point, however, there can be no difference of opin ion; that is, the increasing length and beam of ocean-going vessels require the provision of entrances of ample width, and the more exposed such entrances are to heavy cross seas and strong cross currents the wider they must be in the interests of the navigator. The difficult nature of the present Durban entrance is an example of this. In tidal harbours, and in those with a large volume of river water discharge, an undue restriction of the width of the entrance may produce a current unsafe for navigation. A strong outgoing stream meeting on-shore waves at an entrance is bound to increase the turbulence and create a dangerous sea at a critical point.

The Natural Harbours of America.

The North American continent is well endowed with naturally sheltered harbours in positions where they serve the necessities of sea-borne trade. In the United States deep water river harbours meet these needs at such ports as New York, at the mouth of the Hudson; Phila delphia, on the Delaware, 88 nautical miles from the sea entrance to Delaware Bay; Portland and Astoria (Oregon), on the Colum bia, where, however, dredging has been necessary to deepen parts of the river; and Newport News and other places on the James river, Virginia. Deep land-locked bays or sea inlets provide the harbours of Baltimore, at the head of Chesapeake Bay; Portland (Maine) ; Boston; and San Francisco; and those at Seattle, Tacoma and other ports in Puget Sound.Two of the most important Canadian ports, Montreal and Quebec, are situated on the magnificent river St. Lawrence, the former S5o m. from the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Halifax in Nova Scotia is in a large land-locked, deep-water harbour free from ice all the year round. Vancouver harbour, in the sheltered Burrard inlet, is one of the finest on the Pacific coast and is capable of internal development on a large scale. Victoria and Esquimalt harbours are in well protected inlets at the southern end of Van couver Island; and Prince Rupert, in British Columbia, is a comparatively new deep water port on a narrow and well shel tered arm of the sea.

The finest and most beautifully situated natural harbour in South America is that formed by the land-locked bay of Rio de Janeiro. Buenos Aires, Montevideo and Bahia Blanca are all estuary ports in sheltered positions, but where dredging operations are necessary to form and maintain deep water channels.

New York Harbour.—The harbour of New York (fig. 4) is one of the most perfect natural havens in the world. It enjoys the advantages of ample water area and depth, shelter, good access, a small tidal range—no more than 5 ft. at springs—and moderate tidal streams. The outer harbour, or Lower Bay, is sheltered by the New Jersey shore and Sandy Hook on one side, and by Long Island on the other. The inner harbour is entered through a channel, called the Narrows, between Staten Island on the W. or New Jersey shore, and Brooklyn on the E. It comprises the deep Upper Bay, the rivers which isolate Manhattan Island, namely, the Hudson, East and Harlem, and numerous bays and creeks of which Newark Bay is the most important. The shore lines, under the jurisdiction of the Port of New York Authority (constituted in 1921), have a combined length of over 48o m., and, if the total berthing space of the piers be added, this figure is increased by about 150 m. Excluding the Lower Bay, the shel tered water area within the jurisdiction of the Port Authority is approximately 15o sq. m. In recent years the development of the trade of the port has led to the building of shipping piers on an extensive scale in positions remote from the old centre of trade in Manhattan Island. In this way Staten Island, Jersey City, Newark and the Long Island shores have become busy centres of maritime trade. More recently still, Jamaica Bay, a sheltered inlet on the S. side of Long Island with access direct from the Lower Bay, has been developed as a new centre of port activity.

The

entrance to the Lower Bay is open to the Atlantic, but shelter is afforded by outlying sandbanks. Sandy Hook itself is a long, low spit of sand. Until about 1885 the natural channels through the banks afforded, when suitably marked and buoyed, ample depth and width for all ships using the port. The subse quent deepening of the sea channels, consequent on the growth in the dimensions of transatlantic vessels, has already been referred to. The depths in the sea approaches are now maintained by periodical suction dredging.The entrance to the harbour through Long Island Sound from the N. and E. is sheltered, but the channel is obstructed by rocky islets and reefs. The navigation of this approach was at one time difficult and even dangerous, but it has been much im proved by the removal of many of the rocks by blasting and dredging, notably in the neighbourhood of Hell Gate. The Fed eral authorities, who are responsible for the improvement and maintenance of channels and all aids to navigation in United States harbours and navigable rivers, are now (1928) engaged in still further improving the channels of the Sound and East river, and a low-water depth of 4o ft. over a width of r,000 ft. is aimed at. A large proportion of the berths alongside piers and wharves in New York harbour have depths of 3o ft. or more at low-water and in some of them more than 4o ft. depth is available.

San Francisco.—The land-locked bay of San Francisco is 55 m. long and has a water area of about 420 sq.m. with about 200 m. of shore line. Two large rivers, the Sacramento and San Joaquin, flow into it. The entrance to the bay, known as the Golden Gate, is a mile wide and has a greatest depth of 36o ft.; but a bar outside the Golden Gate has a minimum natural depth over it of 33 ft. at high water (springs rise 51 ft.). The dredging of a chan nel, 4o ft. deep at low water, through this bar was done in 1924-26. There is also a comparatively narrow channel—the North or Bonita channel—affording an entrance to the harbour, which has a natural depth of 54 feet. The usual American plan of water front piers has been followed in the development of the port works at San Francisco.

The Natural Harbours of Australasia.

Some of the most important harbours of Australia and most of the frequented har bours in New Zealand are of natural formation. Pre-eminent is the great land-locked harbour of Sydney, one of the finest and most beautiful in the world. No artificial protection is required and no deepening or enlargement of its entrance channel has been necessary to meet the needs of the largest ships. The outer en trance, facing S.E. between two bluffs, known as the north and south Heads, is less than a mile in width at its narrow est part and has a minimum depth in the channel, nearly i m. wide, of 84 feet. The outer part of the harbour is known as Port Jackson, so named by Captain Cook in 177o. Its shores, as well as those of the upper harbour near and above Sydney, are indented by many sheltered coves. The tidal rise is about 5 ft. at springs and shipping is berthed at open piers. The trade of the port is large, Sydney ranking fifth among the empire ports in this respect. Although only 12 m. in a straight line from the Heads to the upper limit of the harbour, the total length of the indented shore line is 188 miles. Of its water area of 23 sq.m. nearly 5 sq.m. have a depth of over 35 ft. at low water. Channels 4o ft. deep have been dredged where necessary to give access to the overseas piers some of which have berths 45 ft. deep at low water.Melbourne is less fortunately placed than is Sydney, for the city itself is situated on the shallow river Yarra, which discharges into the large land-locked Fort Philip Bay. In its natural state the river had a depth of little more than 13 feet. In recent years dredging at the entrance to the bay and in the approach channels to the wharves at Hobson Bay has increased the minimum depth at low water to 34 feet.

Tasmania has several fine natural harbours. Hobart is a port on the wide 6o ft. deep river Derwent. There is a perfect approach to the river entrance; no dredging is required; open jetties furnish all the needs of shipping and the capacity for extension is almost unlimited. The Tamar provides in its lower reaches a sheltered deep water harbour for the port of Launceston.

New Zealand is rich in good natural harbours. Port Lyttleton in the South Island is a sheltered deep water inlet with no bar. Dredging has only been required to deepen and maintain a chan nel in the approaches to the inner harbour. Wellington, at the southern end of the North Island, is a splendid land-locked har bour with over 3 o sq.m. of sheltered water, from 6 to 14 fathoms in depth. The entrance is 3,60o ft. in width with a depth of 42 ft. at low water. Open wharves, most of which have a low water depth of over 3o ft., and some as much as 36 ft., project from the shores of the inner or Lambton harbour. Auckland harbour, also in the North Island, is an arm of the sea, with an entrance over m. wide, well protected by outlying islands, providing deep water accommodation for the largest vessels.

The Harbours of the East.

The great majority of the impor tant harbours east of Suez are natural havens. Some possess such advantages of depth and shelter that little more than the pro vision of wharves and other internal port works has been neces sary to convert them into first class ports. In others dredging and river training works have been required. Great artificial harbour works in exposed situations such as those at Colombo and Madras are rare in the East ; but harbour works on a very large scale have been made in recent years in sheltered waters, particularly in Japan and the Dutch East Indies and at Singapore. A few only of the more important harbours not already referred to can be mentioned here. The harbour of Bombay is a well sheltered arm of the sea situated between the island of Bombay and the main land. Calcutta and Rangoon are river ports in both of which sand bars and shoals are serious problems (see RIVER ENGINEERING) ; Singapore, one of the greatest trading ports of the east, occupies a sheltered position, protected by outlying islands and shoals, with a deep water anchorage. The new naval base is being made in and on the shores of the channel which separates the island of Singa pore from the mainland of Johore (see DocKs). Hongkong island is situated at the mouth of the Canton river. Between it and the mainland at Kowloon is a natural and well sheltered deep-water harbour of great extent. Kobe and Osaka are large breakwater harbours in sheltered positions in the inland sea of Japan. Yokohama, the principal port of Japan, is in the land locked bay of Tokyo. The port works, including the breakwaters over 12,000 ft. in total length, were partially wrecked by the great earthquake of Sept. 1, 1923, but all the damage has been made good and large additions are being made to the harbour accommo dation. Dairen, the principal port of Manchuria, has been ener getically developed in recent years by the Japanese. It is in a sheltered bay where two island breakwaters and two breakwaters projected from the shore, having a total length of over 21- m., cover a protected water area of 78o acres. At Manila, in the Philippines, breakwaters have been made in an almost land-locked bay to protect a harbour of 1,25o acres.