Steeplechasing and Hurdle Racing

STEEPLECHASING AND HURDLE RACING It was not until 1865 that returns of steeplechasing and hurdle racing came to be officially recorded in the "Racing Calendar," though the first Grand National won by a horse named Lottery was decided in 1839. This sport, which continues from about November to March, while flat racing occupies the rest of the year, is administered by the National Hunt Committee, of which there are about as many members as there are members of the Jockey Club, with six acting as Stewards for the period of their office. Rule 44 of the N. H. Committee is worth quoting as follows : "In all steeplechases Courses except at hunt meetings there shall be:— (A) In the first two miles at least twelve fences, and in each suc ceeding mile at least six fences, in all cases exclusive of hurdles.

(B) For each mile at least one ditch six feet wide and two feet deep on the taking off side of a fence, which ditch may be left open or guarded by a bank or rail, not exceeding two feet in height, and which fence must be at least four feet six inches in height, and if of dead brushwood or gorse, two feet in width.

(C) A water jump at least twelve feet wide and two feet deep to be left open or guarded by a fence not exceeding three feet in height.

In all hurdle races it is stipulated there shall be not less than six flights of hurdles in the first mile and a half, with an additional flight of hurdles for every quarter of a mile, or part of one, beyond that dis tance, the height of the hurdles being not less than three feet six inches from the bottom bar to the top bar." Though there are many instances on record of indifferent flat racehorses passing on to National Hunt racing to do well over fences, it is, nevertheless, as true to-day as it always was that the best steeplechase horses have been specially bred for jumping. The word "specially" is used advisedly, because such horses would be allowed to run to grass and no attempt would be made to break them until reaching three or four years of age. Flat racers we know are put into training as yearlings. Ireland has always been the great home of steeplechasers and it always will be. Their best jumpers have been bred from mares owned by the small farmer to whom the ownership of a mare or two has been a busi ness as well as a pleasure. He has been able to mate his mare for a small fee, and when the offspring has arrived he could afford to turn it out in the paddocks, if not to make a 'chaser then to make a fair price as a hunter. This method of rearing and late "breaking" is responsible for the strength and general development of the great steeplechasers of the past among whom such notable Grand Na tional winners as Jerry M., Manifesto, Kirkland, Troytown, Ser geant Murphy, and Shaun Spadah.

Liverpool, where the Grand National Steeplechase takes place towards the end of March every year, is, perhaps, the true home of steeplechasing in England, though the National Hunt Com mittee's own meeting extends over three days and takes place in March at Cheltenham. Still the Grand National has world-wide fame. The fences at Aintree are recognised as the most formidable anywhere, and no horse that stays the distance of 4 m. 856 yd. and jumps the thirty or so fences, including such notable obstacles as Becher's Brook and Valentine's Brook, is undeserving of his victory even if he be such a humble individual as Tipperary Tim, who in a record field of 42 starters in 1928 proved to be the only horse to escape a fall for which all sufficient reason he came in alone. The value of the race increased until in Tipperary Tim's year (1928) it was worth Li 1,18o to the winner's owner.

At most racecourses on which flat racing takes place, notable exceptions being Newmarket, Ascot, Goodwood, Doncaster, York and certain others, National Hunt racing takes place in season. The sport does not arouse such wide interest as flat racing, but, in spite of unpleasant English weather conditions, it is enormously popular. It is a fact that both steeplechases and hurdle races are run at a faster pace to-day than twenty or fifty years ago. Again the reason has to do with the change in jockeyship, for the revolution noted in jockeyship on the flat re-acted with the jockeys over fences and hurdles. Especially is this true of hurdle racing. The National Hunt jockey of to-day has pulled up his irons by several holes. He does not tarry when the start takes place, but races for the first fence or for the first hurdle as if there were no such obstacle there. The result is that steeplechases and hurdle races are usually truly run throughout, but whether the standard of jockeyship can be the same, and certainly the standard of horsemanship cannot be as high, is doubtful.

Racing in France.

Subsequent to the World War, because of the poor feeding of mares and their young stock and the com parative neglect of the stallions, French racing was in a bad way. It may explain why on three occasions horses sent from England were able to win the Grand Prix de Paris in successive years, Galloper Light (1 919) Comrade (192o) Lemonora (1921) . That horses from England have not won since 1921 is indicative of the remarkably fine recovery of horse-breeding and racing in France. Not only so but horses have been sent from France to win some of our important races. Thus Sir Gallahad III. and Tapin won the Lincolnshire Handicap; Epinard, one of the best horses foaled in France since the war, won the Stewards' Cup at Goodwood, and was rather unluckily beaten by a neck for the Cambridgeshire • Forseti won the Cesarewitch ; Masked Marvel and Insight II. were Cambridgeshire winners for the American, Mr. Macomber, who races and breeds on a big scale in France; Asterus won the Royal Hunt Cup in 1927; and in 1928 Palais Royal II. owned by the Belgian, M. Wittouck, but bred and raced in France, won the Cambridgeshire after running second to Fairway for the St. Leger.It is recognised that the French breeders to-day are producing some high-class horses capable of winning races in any part of the world, for if they can win in England they certainly should be able to win anywhere else. That British breeders have recognized this as a fact is shown by their patronage of leading French stallions. Mares have been sent over specially to be mated with them while yearlings have been purchased for England at the annual sales at Deauville. Lord Derby, who races in France in partnership with the American, Mr. Ogden Mills, has met with remarkable success. The horses Kantar and Cri de Guerre were very impor tant winners for the partnership in 1928. The latter won the Grand Prix, and, in all, horses owned by them won about two million francs in stakes in 1928, the same year as Lord Derby headed the list of winning owners in England with the wonderful total of L65,603.

Jockeys' and Entrance Fees.

According to the Rules of Racing, jockeys' fees, unless there is a private registered agree ment between the jockey and the owner or trainer, are as follows: For flat racing £5.5.0 for a winner and £3.3.0 for a loser.For Steeplechasing. Where a race under the National Hunt Club rules is worth £85 or more to the winner the fees are f 10.10.0 for a winner and £5.5.0 for a loser. If the race is worth under that amount, the fees are £5.5.0 for a winner and L3.3.0 for a loser.

The entrance fees for some less important races, such as selling plates, are as low as Li to £2; but in some of the classics a system of forfeits prevails.

For the Grand National of 1929, the closing date was Jan. 1, 1929. If the horse was not withdrawn by Jan. 22, f5 had to be paid. If left in the race after Jan. 22, an additional £25. In 1928 a new ruling was passed enacting an additional L25 to be paid after Mar. 12. The fee for starters or horses not withdrawn after this date being an extra £ 20 making £ in all; none of these fees or forfeits are collected until after the races have been run.

(S. Gv.) The early history of horse racing in America still awaits ade quate and systematic treatment, its records being scattered through a wide range of documents, often of a fugitive and fragmentary description. But the passion for the sport so highly developed in England seems to have been firmly implanted in the Colonies at a very early date. The Puritan regime in New England and the Dutch settlement of New York left racing to become established first in the south, notably Maryland, Virginia and the Carolinas, where the "cavalier spirit" prevailed among the leaders of both social and civic life. As soon as the Dutch dominance was suc ceeded by the English in New York, the turf began rapidly to develop there also, but in Pennsylvania the Quaker influence was a strong deterrent, resulting in restrictive legislation.

From such scanty records as survive it is evident that the horse known to modern times as "thoroughbred" was being established, as a breed, in the New World contemporaneously with his estab lishment in the Old, by the constant importation of choice speci mens and their use for both racing and breeding purposes. Long before the General Stud Book was first published in England, the Jockey club was organized or any of the fixed events termed "classics" were instituted there, the colonial magnates, north and south, were constantly importing both stallions and mares of the best blood and individually famous. These, crossed upon the na tive stock or interbred among themselves, were the founders of the American thoroughbred of to-day. So far as is known, the first truly thoroughbred horse ever brought over from England was Bull (or Bulle) Rock, a son of the Darley Arabian and a mare by the Byerly Turk, foaled 1718 and imported into Virginia about 173o. He seems to have initiated a period of tremendous expan sion, as within the next 3o years Virginia, Maryland and the Caro linas were rapidly populated by a race of fast-multiplying thor oughbreds of the best British blood. The early racing had been at short distances, but the so-called "quarter horses" which supplied it were supplanted by an improved type, racing heats of 3 and 4 m., which, the latter especially, long remained the approved test.

The Revolutionary War naturally had a paralysing effect upon the sport. New York was much of the time in the hands of the British and the region round about it was one of uninterrupted warfare, while Virginia and the Carolinas were fought over inces santly.

After peace came in 1783 it required several decades for recup eration on the part of the impoverished and exhausted combatants of the United States. But re-importation soon became prevalent, and the establishment of new race courses and turf bodies all along the Atlantic coast from New York to Savannah progressed rapidly. Meanwhile, the interest in the sport was spreading be yond the Allegheny mountains, and the pioneers of Kentucky and Tennessee were taking with them some of the best animals that the older States could provide. This interest also extended farther west to Alabama, Louisiana and Mississippi. New Orleans was destined by the middle of the 19th century to be the foremost racing point in America. With the gradual centralization of wealth in and about New York it naturally became a focus for sport and for outdoor recreation, while Virginia and the Carolinas, owing to economic changes, were losing prestige; Virginia's long premier ship in turf affairs, especially in breeding, passed to Kentucky, whose ascendancy, once gained, was to be permanent. As the frontiers were continually pushed to the west, the racehorse fol lowed or went with the "covered wagon" until at length the dis covery of gold in California, in 1849, an impetus for a transcon tinental migration, carried him to the Pacific coast itself.

Effect of the Civil War.

For a second time war—the Civil War—intervened to disturb turf affairs, which went into almost total eclipse during this period. With it the last traces of Virginian prominence on the course and at the stud were swept away, while the leadership of New Orleans was shattered for ever. Kentucky suffered severely but temporarily only, while with the cessation of hostilities in 1865 the North took command of the affairs of the thoroughbred, never to relinquish them. The great metro politan racing plants began to dot the map, and the "absentee landlords" to acquire control of the great stud-farms of the "Blue Grass" region of Kentucky, the most prolific breeding ground of the champions of the 20th century. At the dawn of the loth century the skies were bright. By 1912 the situation had be come so disastrous that many courses were closed, hundreds of animals were being exported any and everywhere and sold for any thing they would bring, and other hundreds, their identities de stioyed, converted to the most menial uses. Then came the turn of the tide. An upward ascent was begun and the sport reached a prosperity previously undreamed of. The economic depression that began in 1929 naturally affected racing materially but it has since regained much of the loss then experienced and in 1934 the number of races run over North American tracks reached the record total of 14,261, of an aggregate value of $10,443,495, about 10,00o different horses competing.

Modern Tracks.

The great centre of the sport is, however, New York, which supports four major tracks, those of Belmont park, Aqueduct, Jamaica and Empire City park. During midsum mer the scene shifts to Saratoga, to the northward, where also the annual yearling sales are held. Maryland supports four tracks, all contiguous to Baltimore—Pimlico, Laurel, Bowie and Havre de Grace. Chicago also supports four major plants : Lincoln Fields, Arlington park, Washington park and Hawthorne, with a fifth near at hand, Aurora. In Kentucky, Louisville has Churchill Downs, where the Kentucky Derby is run, and Latonia just across the Ohio river from Cincinnati. St. Louis supports Fairmount park, just across the river (Mississippi) in Illinois. A feature of the past few years has been the passing of new racing laws in several leading states, including Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Rhode Island, in New England; in New York, Michigan, Illinois, West Virginia, Florida, Texas, California, etc., and in response new racing plants have sprung up in all these localities, often of mag nitude. In Canada meetings are given at Woodbine park, Toronto; at Windsor and Fort Erie, also in Ontario, and elsewhere.Practically all American racing is over circular tracks from which the turf has been removed, the surface aiding a high rate of speed. The track at Belmont park (the Westchester Racing Association, on Long Island) is the largest, being an oval some what more than II- m. in circumference, with a subsidiary special straightaway, the Widener course, of about seven furlongs, over which the Futurity, the leading annual event for two-year-olds, is decided. Its value in 1928 (gross) was $128,390, of which $97,790 went to the winner, High Strung, it being the most valuable prize ever run for in America. It is obvious that computations of money winnings no longer constitute a criterion of class in Amer ica, as it is possible for one lucky animal, though of mediocre calibre, to win more in a single effort than an absolute champion could in his entire career in former eras. Therefore, much con troversy exists as to the real merits of latter-day horses as com pared with those of the past.

Man o' War, which raced in 1919-20, is by consensus one of the supreme thoroughbreds of history; nor can there be any question of the real class of other modern heroes such as Cru sader (son of Man o' War), Exterminator, Equipoise, Twenty Grand, Cavalcade, Discovery or Gallant Fox.

But their exploits have not dimmed those of such horses of the past as Hindoo and his son Hanover, Luke Blackburn, Salva tor, Henry of Navarre, Sysonby and others; nor, to go even far ther back, Longfellow, Ten Broeck, Harry Bassett, Norfolk, Aste roid, Kentucky or Iroquois, the only American winner of the Epsom Derby. That no modern mare approaches the turf queens of earlier history—Miss Woodford, Firenze, Imp, Yo Tambien, Beldame or Thora—is admitted. The vogue of the short-distance race, or sprint, is attributable wholly to commercialism in its vari ous forms and, in particular, to the dominant desire for a quick "turn-over" of his money by the owner, the trainer, the speculator and the track manager alike. At best turf gains are problematical, the losses for the most part certain. The expense of production has mounted to altitudes which formerly would have seemed fan tastic. Hence the prevalence of two-year-old racing, which has become a positive abuse, and the gigantic stakes offered for that age, which in their turn have inflated yearling values enormously. In the span of 20 years the differences shown are startling. In 1908 in the United States 745 yearlings were sold at auction for a total of $256,82o, the average price per head being $344• In 1927 a grand total of 703 were sold for $1,939,425, the average per head being $2,758.78. Economic adversity then brought a big fall in values, but now (1935) large prices are again the rule. The racing of two-year-olds begins on Jan. 1 at the winter meetings in Florida, California and Louisiana.

Breeding.

Kentucky enjoys a practical monopoly of breeding prestige, and from her Blue Grass pastures come annually a large proportion of the season's best performers. No breeder of the present day operates on the unexampled scale of the late J. B. Haggin, who at one period, at his twin establishments, Elmendorf, in Kentucky, and Rancho del Paso, in California, was using 4o different stallions and over 600 brood mares—the nearest approach to "mass production" that the thoroughbred breed has known. But the number of large establishments is a marked feature and there has been a return to Virginia by several leading breeders. Imported—chiefly English, with a small quota of French and Ger man—stallions and brood mares are constantly being brought into the country for stud purposes, but curiously enough, of the many horses imported since about 188o, none has been able to found what seems like an enduring line, the dominant ones of the day tracing to Australian, imported in 1858 ; Eclipse (son of Orlando), imported in 1859; and Bonnie Scotland, imported in 1857. How ever the Bend Or line has lately furnished a premier sire in Sir Gallahad III, bred in France. The earlier line from Glencoe is now almost extinct, as is that from Diomed. The latter reached its apogee in Lexington (1850-75), still, over a half-century after his death, the most famous thoroughbred ever produced in America. His male line has faded but his blood is everywhere throughout the fabric of the American racehorse, testifying to an influence in its way unprecedented. Leamington, brought over in 1865, with those progenitors just named, ranks as the greatest since the 18th century, but his blood has been in capable of carrying on directly after the passing of his sons, and is now no longer to be reckoned with. The foreign attitude toward the American thoroughbred for breeding purposes has never been friendly, despite the successes that many American-bred horses have won abroad and the fact that foreign-bred horses brought to America have never, taken as a class, shown any superiority. Yet strains of American blood have, from time to time, cropped up in the classic stake winners of England, France, Germany, Italy and also the Antipodes, including more than one Derby winner.

Jockeyship Methods.

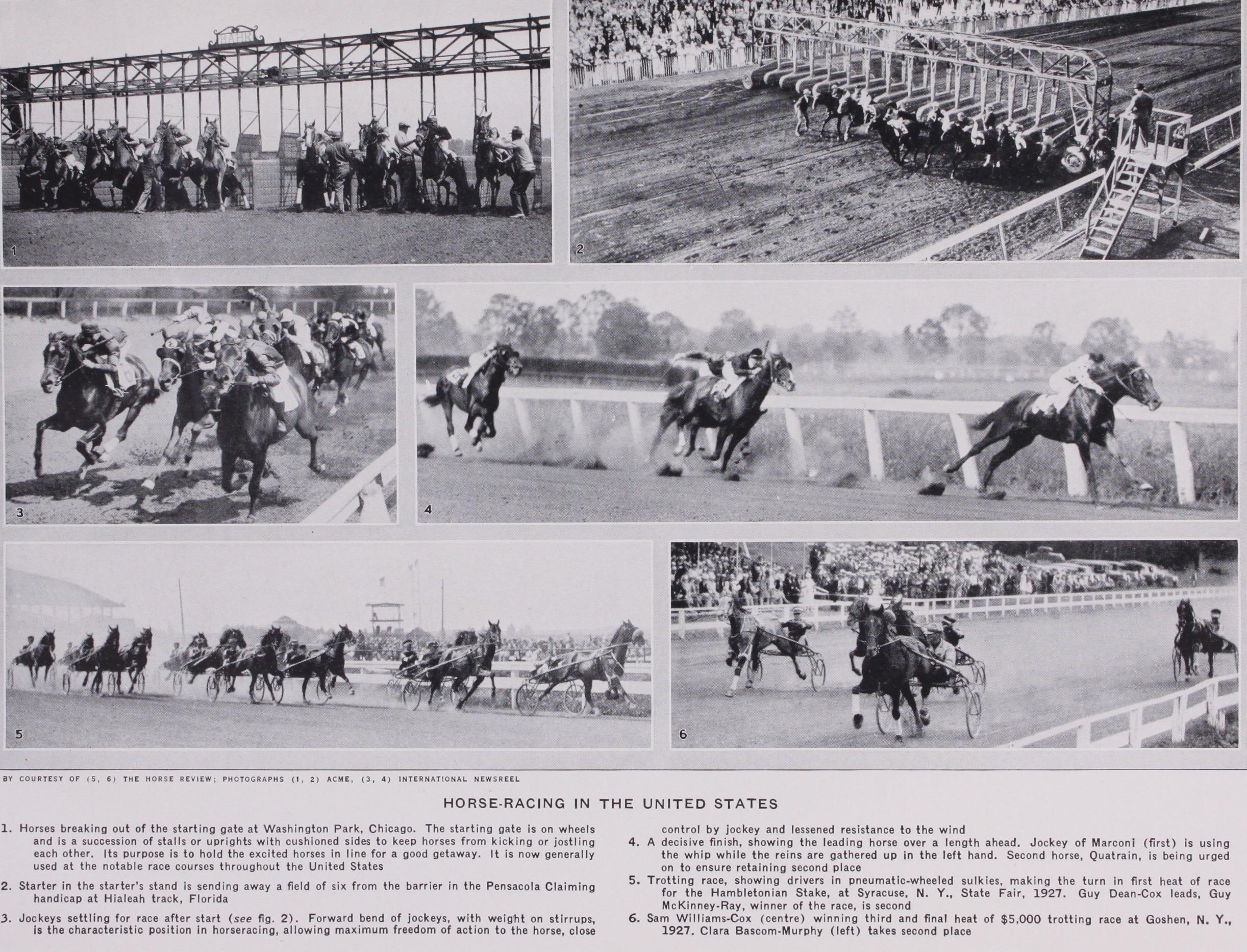

It seems to be conceded that American methods of jockeyship since the 19th century permanently revo lutionized race riding, and the entire scope of the sport, throughout the world, has felt their effects. But America for years has suf fered from a dearth of good riders, while great ones have become well-nigh unknown. Two reasons are advanced for this some what curious situation. One is the prevalence of the sprinting distances, making judgment of pace, generalship and similar qual ities ineffective amid the general scrambles that ensue. The other is the fact that the American weight scale is so low that riders of matured skill and experience become virtually outlawed from the saddle just when their skill is growing most assured, because of their excess weight. Many of them have emigrated to Europe and there continued to ride for seasons with conspicuous success, the loss to their own country being proportionate.Internationally the entente cordiale between America and the Old World is, however, well sustained, evidences of which were provided by the voyage across the Atlantic, in 1923, of Papyrus and his match race against the American colt Zev, run at Belmont park, of which Zev was the winner; and the three American appearances of the French colt Epinard, in 1924, in which he ran second, successively, to Wise Counsellor at Belmont park, to Ladkin at Aqueduct and to Sarazen at Latonia, the last named race being perhaps the most brilliant seen on the American turf in the 20th century. (J. L. HE.)