Battle of Ilipa

ILIPA, BATTLE OF, 206 B.C. This was the culminating battle of the campaigns by which Publius Cornelius Scipio (q.v.), afterwards named Africanus, overthrew the Carthaginian power in Spain, and thereby paved the way for his subsequent campaign in Africa which ended in the defeat of Hannibal at Zama (q.v.) and the capitulation of Carthage. In military history Ilipa ranks with Gaugamela and Cannae as one of the supreme tactical mas terpieces in the military history of the ancient world, and indeed outshines any as an example of a victory ensured by the disloca tion of thought and will produced in the mind of one commander by the other before even the fighting troops came into contact. After suffering a series of defeats since Scipio's opening seizure of Cartagena (q.v.) in the spring of 206 B.C. the Carthaginians made their last great effort. Hasdrubal Gisco, encouraged by Mago, Hannibal's brother, raised and armed fresh levies, and with an army of 70,00o foot, 4,00o horse and 32 elephants marched north to Ilipa (or Silpia), which was not far from where Seville stands to-day. Scipio moved south from Tarraco to meet the Carthaginians, collecting auxiliaries on his way. Advancing to the neighbourhood of Ilipa with a total force, Romans and allies, of 45,00o foot and 3,00o horse, he came in sight of the Cartha ginians, and encamped on certain low hills opposite them. It de serves notice that his advance was on a line which, in the event of victory, would cut them off from the nearest road to Gades, this road running along the south bank of the Baetis River.

The two camps lay facing each other across the valley between the two low ridges. For several successive days Hasdrubal led his army out and offered battle. On each occasion Scipio waited until the Carthaginians were moving out before he followed suit. Neither side, however, began the attack, and towards sundown the two armies, weary of standing, retired to their camps—the Carthaginians always first. One cannot doubt, in view of the upshot, that on Scipio's side the delay had a special motive. On each occasion also the legions were placed in the Roman centre opposite to the Carthaginian and African regulars, with the Span ish allies on the wings of each army. It became common talk in the camp that this order of battle was definite, and Scipio waited until this belief had taken firm hold.

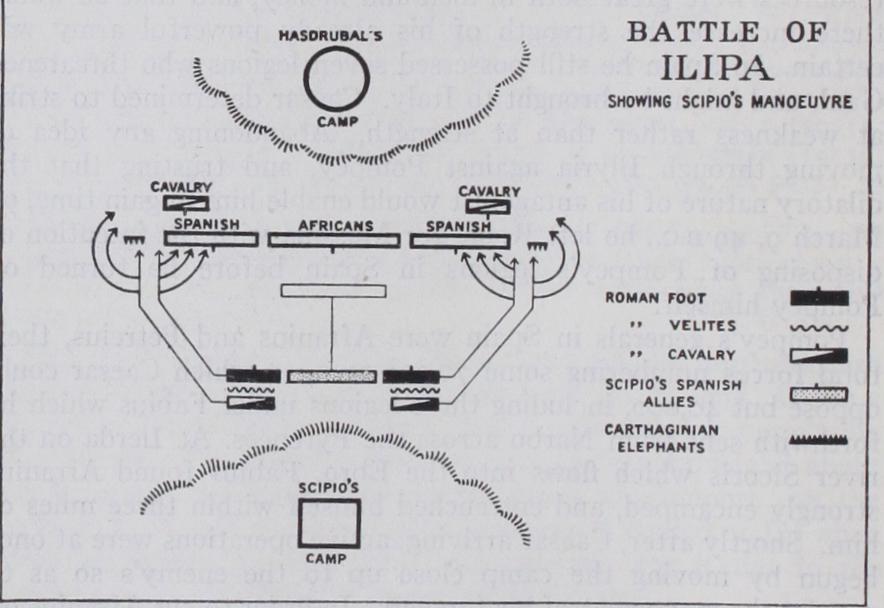

Then he acted. He had observed that the Carthaginians made their daily advance at a late hour, and had himself purposely waited still later, to fix this habit on his opponent's mind. Late in the evening he sent orders through the camp that the troops should be fed and armed before daylight, and the cavalry have their horses saddled. Then, while it was scarcely yet daylight, he sent on the cavalry and light troops to attack the enemy's outposts, and himself followed with the legions. This was the first surprise change, and its effect was that the Carthaginians, caught napping by the onset of the Roman cavalry and light troops, had to arm themselves and sally forth without a meal. It further ensured that Hasdrubal would have no time to alter his normal disposition even should the idea occur to him ; for the second surprise change was that Scipio reversed his former order of battle, and placed the Spanish in his centre and the legions on the wings. The Roman infantry made no attempt to advance for some hours, the reason being Scipio's desire and design to let his hungry opponents feel the effects of their lost breakfast. There was no risk to his other surprise change by so doing, for once drawn up in order of battle, the Carthaginians dared not alter their array in face of a watchful and ready opponent.

It was about the seventh hour when he ordered the line to advance, but the Spanish centre only at a slow pace. On arriving within Boo yards of the enemy, he himself, leading the right wing, wheeled to the right, and made an oblique advance out wards. The left wing executed a similar movement. Advancing rapidly, so that the slow-moving centre was well refused, the Roman infantry cohorts wheeled successively into line as they neared the enemy's line, and fell directly on the enemy's flanks, which but for this manoeuvre would have overlapped them. While the heavy infantry thus pressed the enemy's wings in front, the cavalry and light infantry, under orders, wheeled out wards again, and, sweeping round the enemy's flanks, took them in enfilade. This convergent blow on each wing, sufficiently dis locating because it forced the defenders to face attack from two directions simultaneously, was made more decisive in that it fell on the Spanish irregulars. To add to Hasdrubal's troubles, the cavalry flank attacks drove his elephants, mad with fright, in upon the Carthaginian centre, spreading confusion. All this time the Carthaginian centre was standing helplessly inactive, unable to help the wings for fear of attack by Scipio's Spaniards, who threatened it without coming to close quarters. Scipio's calcula tion had enabled him to "fix" the enemy's centre with a minimum expenditure of force, and thus to concentrate the maximum for his decisive double manoeuvre.

Hasdrubal's wings destroyed, the centre, worn out by hunger and fatigue, fell back, at first in good order ; but gradually under relentless pressure they broke up and fled to their entrenched camp. A drenching downpour, churning the ground in mud under the soldiers' feet, gave them a temporary respite and prevented the Romans storming the camp on their heels. During the night Hasdrubal evacuated his camp, but as Scipio's strategic advance had placed the Romans across the line of retreat to Gades, Has drubal was forced to retire down the western bank towards the Atlantic. Nearly all his Spanish allies deserted him.

Scipio's light troops were evidently alive to the duty of main taining contact with the enemy, for he got word from them as soon as it was light of Hasdrubal's departure. He at once followed them up, sending the cavalry ahead, and so rapid was the pursuit that, despite being misled by guides in attempting a short-cut to get across Hasdrubal's new line of retreat, the cavalry and light infantry caught him up. Harassing him continuously, by attacks in flank or in rear, they forced such frequent halts that the legions were able to come up. "After this it was no longer a fight, but a butchering as of cattle," till only Hasdrubal and 6,000 half armed men escaped to the neighbouring hills, out of 70,000 odd who had fought at Ilipa.

Military history contains no more classic example of general ship than this battle of Ilipa. Frederick's "oblique order" ap pears immature beside Scipio's double oblique manoeuvre and envelopment, which effected a crushing concentration of strength against weakness while the enemy's centre was surely "fixed." Scipio left the enemy no chance for the change of front which cost Frederick so dear at Kolin. Masterly as were his battle tactics, still more remarkable perhaps were the decisiveness and rapidity of their exploitation, which had hardly an equal in mili tary history until Napoleon came to develop the pursuit as the vital complement of battle and one of the supreme tests of generalship. (B. H. L. H.)