Campaign of Ilerda

ILERDA, CAMPAIGN OF (49 B.c.). On Dec. 17 Julius Caesar, the leader of the democratic party in the Second Civil War, crossed the Rubicon and in sixty days was master of Italy. As he failed however to shut Pompey up in Brundisium, this gen eral sailed for Dyrrachium. The problem which now confronted Caesar was a complex one. He was without a fleet, and though the aristocratic party was no longer in the ascendant, Italy was still at Pompey's mercy because he could cut her off from her grain supplies in Egypt, Sicily and Sardinia. In Greece Pompey's resources were great both in men and money, and that he would there increase the strength of his already powerful army was certain. In Spain he still possessed seven legions who threatened Gaul, and might be brought to Italy. Caesar determined to strike at weakness rather than at strength. Abandoning any idea of moving through Illyria against Pompey, and trusting that the dilatory nature of his antagonist would enable him to gain time, on March 9, 49 B.c., he left Rome for Massilia with the intention of disposing of Pompey's legions in Spain before he turned on Pompey himself.

Pompey's generals in Spain were Afranius and Petreius, their total forces numbering some 70,00o men, to which Caesar could oppose but 40,000, including three legions under Fabius which he forthwith sent from Narbo across the Pyrenees. At Ilerda on the river Sicoris which flows into the Ebro, Fabius found Afranius strongly encamped, and entrenched himself within three miles of him. Shortly after, Caesar arriving, active operations were at once begun by moving the camp close up to the enemy's so as to restrict the movement of his foragers. In order to cut Afranius off from the bridge at Ilerda, Caesar attempted to occupy a ridge which lay between the camps, but the XIV. legion was driven back. Counter-attacking with the IX. legion he drove a large party of the enemy into Ilerda and then tried to assault this city by forcing his way up a ravine ; here he nearly met with a disaster, and had much difficulty in extricating himself.

Two days after this battle, which reflected no great credit on Caesar, his bridges over the Sicoris were swept away by a flood, and his communications with Gaul severed; worse still, his con voys could no longer reach him. Learning that he was expecting a large convoy, Afranius crossed the bridge at Ilerda with three legions and all his cavalry and attacked it. The attack, however, failed, and Caesar building a boat bridge 22 miles north of his camp enabled his convoy to cross, and his cavalry to attack Afranius's foragers.

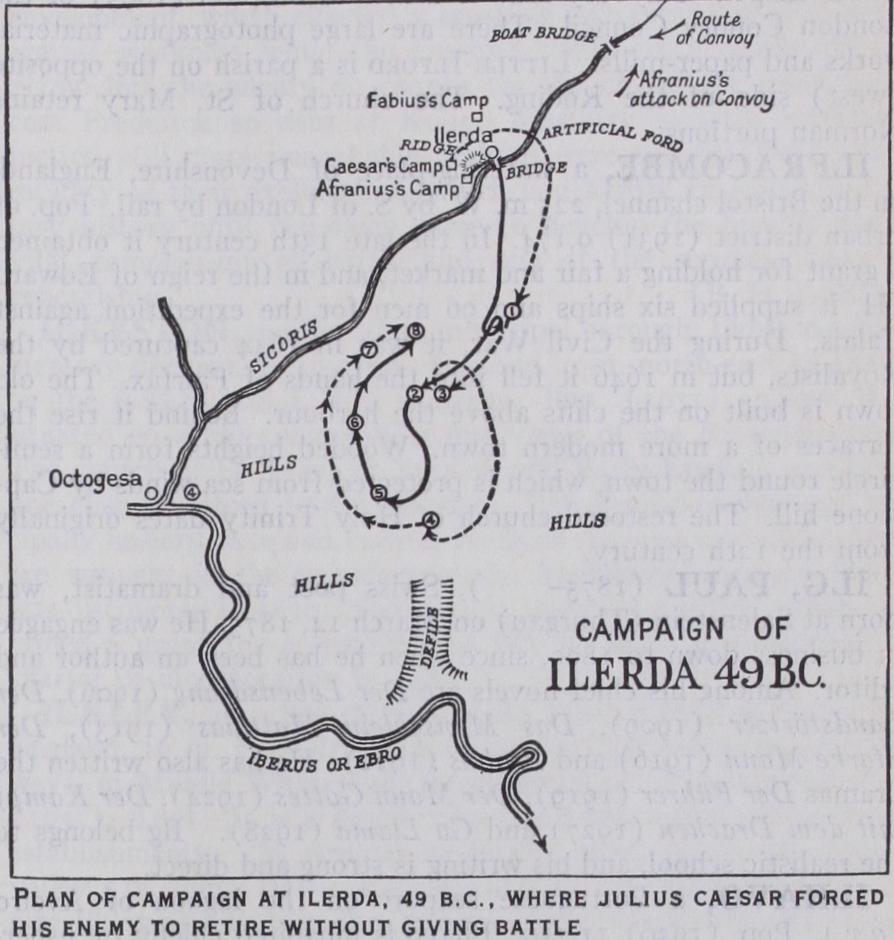

In order further to restrict his enemy, by running the river into a number of artificial channels he created a ford near his camp which forced the Pompeians to transport two legions over the Sicoris to protect their communications, and then, on June 23, still holding the bridge they crossed their whole army over to the left bank, and set out towards the Ebro. Caesar having now dis lodged his enemy, his next step was not to defeat him but to force him to surrender. Not only would this save him casualties but augment his army, as all prisoners would be incorporated in it. He wished to gain his object by manoeuvring rather than by fighting. Sending his Gallic cavalry over the ford, these nimble horsemen greatly impeded the enemy's march, and gained time for Caesar to cross his infantry. The manoeuvres now carried out were remarkable, and are shown on the plan. (I) Caesar rapidly followed Afranius and forced him to form front; (2) Afranius retired skirmishing, Caesar following; (3) Afranius de cided to retire on Octogesa, Caesar pretending to withdraw, and Afranius made towards the defile; (4) Caesar counter-marched and cut him off from the defile; (5) Afranius reverted to retire ment on Octogesa; Afranius was now strategically beaten, and Caesar could have annihilated him but refused to do so; (6) Afranius made for the Sicoris to obtain water ; (7) Caesar headed him off ; (8) Afranius attempted to regain Ilerda, but was forced to surrender on July 2. The result of these masterly and blood less manoeuvres were, that not only did Pompey lose Spain but also his oldest and best legions, and simultaneously Caesar at little loss added immensely to his own strength. Of their kind the manoeuvres of Ilerda have seldom been rivalled and never sur passed. See PHARSALUS, BATTLE OF. (J. F. C. F.)