Early Mediaeval

EARLY MEDIAEVAL Har§a : Nalanda.—Harsavardhana in the first half of the seventh century revived the glories of the diminished Gupta empire. He may be regarded as responsible for the restoration of the great monastery at Nalanda, and for the transition from Gupta to mediaeval art in Magadha generally. He also took possession of the Valabhi kingdoms of Kathiawar and Gujarat; but was defeated by the Calukyan king Pulakesin II. A more detailed account can be given of early mediaeval art in the Dek khan and the far south.

Pallavas.

The Pallavas originated in the Kistna-Godaveri area, inheriting the artistic tradition of the eastern Andhras. Forced to move southward about 600, the sudden appearance of architecture and sculpture in stone is due to the accomplished Mahendravarman I. (600-625) ; we know from one of his inscrip tions that up to this time structural temples had been built of brick, timber, copper and mortar, and the implied absence of stone construction corresponds to and explains the appearance of Pallava art already fully evolved in the 7th century. All the sculpture at Mamallapuram, including that of the excavated and monolithic temples (the "Seven Pagodas"), and also the great rock-cut relief representing Bhagiratha's penance and the Descent of the Ganges belong to the first half of the 7th century. The sculpture here, Pauranik in theme, for the Pallavas were Hindu kings, is of a very high order. In the early 8th century the sculp ture develops in more strictly architectural application, in connec tion with the great structural temples at the Pallava capital, Kancipuram, passing in the 9th into that of the Cola period. Painting which has been assigned to the time of Mahendravar man I. has been found in a Jaina excavation at Pudokottai.

Early Calukyan.

Some temples with sculptures at Badami antedate Pulakesin I. (550-566), founder of the dynasty. Later artistic history shows a mixture of northern and southern ele ments, but is mainly a development of Pallava forms. The Brah manical caves at Badami and Aihole (especially Cave III., date A.D. 578) contain a series of large and important reliefs illustrating Pauranik mythology and legend. Worthy of special mention also are the sculptured roofing slabs from Aihole, dating from the early 7th century, and now in the Prince of Wales Museum, Bombay. The Virupaksa, most important of the structural temples at Pattadkal was built about 740, probably by architects and masons brought from Kancipuram, and shows a corresponding Pallava character in the sculptured reliefs. The Buddhist caves at Auran gabad, dating from the late 6th and early 7th century contain many important figures. At Elura, the Das Avatara, Ravana ka Khai, Dhumar Lena and Ramesvara caves appear to range from 65o to 75o.Rastrakuta.—The Rastrakutas succeeded the Calukyas in the Western Dekkhan in 753. Their most important monuments are at Elura and Elephanta; the latter are easily accessible in an afternoon from Bombay. At Elura the famous rock cut Kailasa natha temple, a huge and complete monolithic shrine excavated in the side of the hill, is in a purely Dravidian style, immediately derived from that of the Virupaksa at Badami ; of the very nu merous sculptures illustrating 8aiva subjects, the finest represents Siva and Parvati seated on Mt. Kailasa, with Ravana imprisoned within the mountain below, endeavouring to cast it down, and succeeding in causing a tremor; this, and the Varaha Avatar of Udayagiri, above alluded to, are the finest examples of reliefs which deal with what may be described as cosmic or geotectonic themes. Remains of painting on the ceiling of the porch of the upper storey are of two periods, in part no doubt of the eighth century and nearly contemporary with the actual shrine; these are the oldest surviving Brahmanical frescoes, but literary refer ences show that painting had been practised both as a religious and secular art from time immemorial.

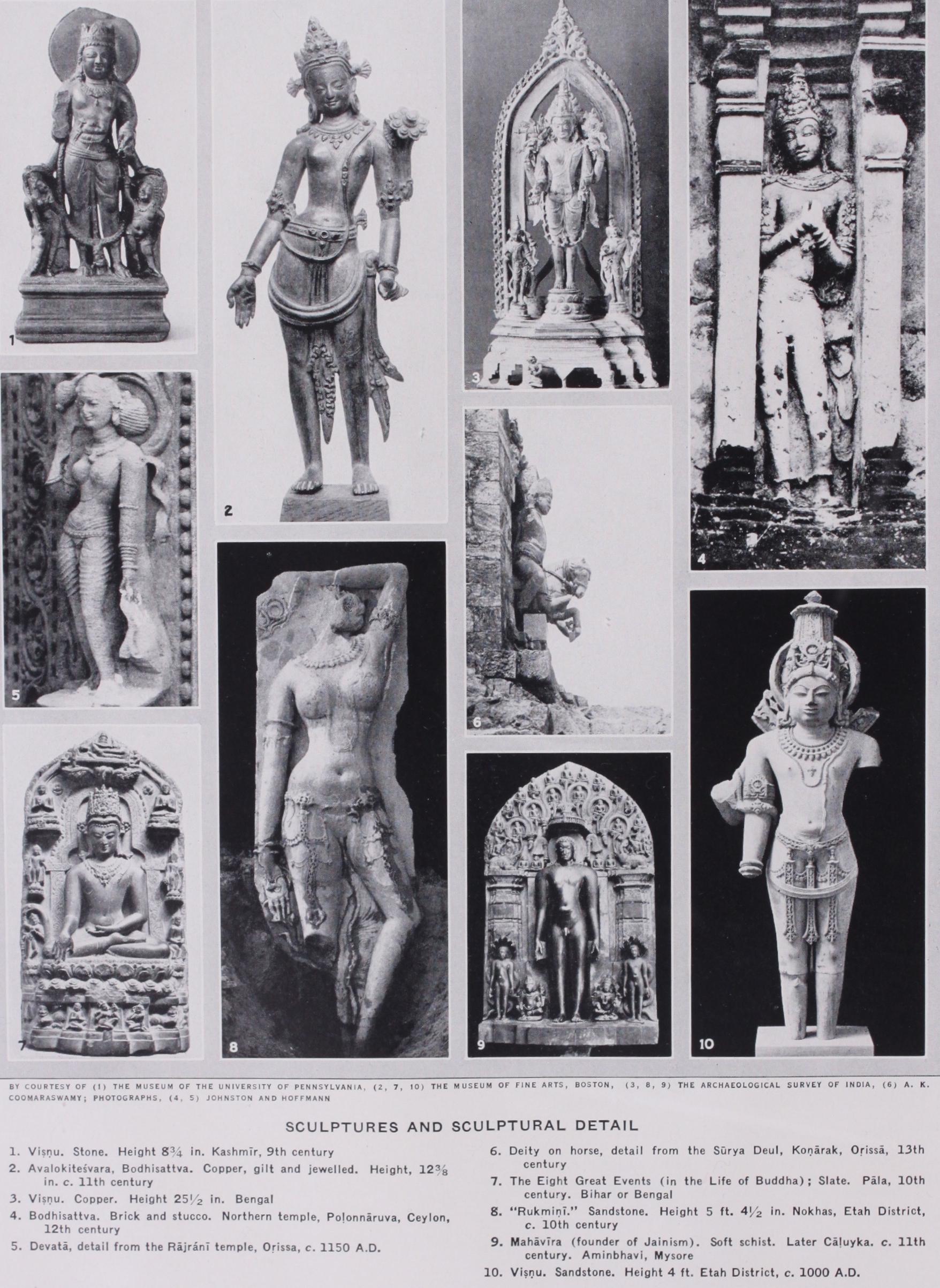

At Elephanta, the most famous, and perfectly preserved sculp ture is a colossal relief in the main excavation, a three-headed bust, which has often, though incorrectly been called a Trimurti; it is actually an icon of Siva in the form known as Mahesa, and many other examples exist, of which one of the best is a later relief in the Pennsylvania University Museum.

Kashmir.—The old town of Vijrabror has yielded early sculp tures in which the influence of the Graeco-Buddhist art of Gand hara is still apparent ; the most interesting of these are representa tions of the goddess of Fortune, Laksmi, seated with a cornucopia, and these types can be followed well into the mediaeval time, grad ually becoming completely Indianised. The remains of a tiled cock-pit of about the 5th century at Harvan are unique; the devices on the moulded tiles represent men seated, and in bal conies; equestrian archers in chain armour, deer, fighting cocks, lotuses, and a fleur-de-lys motif ; in technique they recall the so called Han but probably later grave-tiles of China.

The Vantipor temple sites of early 9th century date have yielded small and admirably executed stone figures of Visnu in a style peculiar to Kashmir and the neighbouring States of Camba and Kulu, and with these there appear also Siva types, including a three-headed Mahesa, and an Ardhanarisvara. Similar Vaisnava images of brass inlaid with silver and copper have been found in together with a Buddha image in the same technique, but of earlier (late Gupta) date. Buddhist "bronzes" found in Kash mir, and ranging from the 6th to the nth th century, show that Buddhism survived to a late date, although it had already declined by the end of the 8th century, all the foundations of Avantivar man in the 9th being Brahmanical. The stone sculpture architec turally associated with the great temples in Kashmir is unfortu nately almost all in a ruined state.