Electrical Instruments

INSTRUMENTS, ELECTRICAL. On account of the great extension of electrical power supply, cable and radio teleg raphy and telephony, and research, electrical measuring instru ments have become extremely numerous of recent years ; and it is therefore desirable to preface a description of the leading types by a short summary and classification of their principles.

In order that an electric current should flow through a con ductor, there must be a potential difference, or P.D., usually ex pressed in volts, between its ends. The resulting current expressed in amperes always produces two effects : (a) an external magnetic field encircling the conductor and proportional to the current, and (b) an internal heating of the conductor due to agitation of its molecules which is proportional to the square of the current. If the conductor is a liquid compound or electrolyte, the passage of the current also produces a separation of its constituents or electrolysis, causing a liberation of gas or deposition of metal, the amount of which is proportional to the current and to the time for which it passes. All these three effects of the current have been employed as bases for its measurement. Conversely, the introduction of a magnetic field into a circuit (dynamo or transformer), or the heating of the junction of two conductors (thermopile), or chemical action (voltaic cell) causes an electro motive force to be set up, and electrical instruments based on these effects are in use. In addition when a difference of poten tial exists between two conductors there is an electrostatic attrac tion between them which can be used as a method of measuring the P.D.; and when electrified particles or electrons are projected across a vacuous space as in a valve tube they can be deflected either by electrostatic attraction or a magnetic field.

The steady current in a metallic conductor in amperes is equal to the P.D. in volts between its terminals divided by its resistance in ohms; and resistance measuring devices form a very important section of electrical instruments, with which are associated potentiometers for P.D. and current measurement. The power taken from or imparted to a circuit in Watts at any instant is obtained by multiplying the P.D. in volts by the current in amperes at that instant, and wattmeters enable this power to be directly indicated; while the energy consumed, generally meas ured in kilowatt hours or Board of Trade units (B.T.U.), is obtained by multiplying the power in kilowatts (I,000 watts) by the time in hours it is utilized, and is registered by energy meters; but if the supply P.D. is constant the product of the current and time or quantity of electricity is sufficient and is indicated by quantity meters.

Inductance and capacity are two electrical quantities which are of great importance in electrical circuits especially with high fre quency alternating currents. The former is the magnetic field which is linked with the circuit whenever a current flows through it, and therefore produces an e.m.f. whenever the current is increasing or diminishing, just as a mass resists acceleration or change of its velocity. The unit of inductance is termed the Henry (after the American physicist Joseph Henry, q.v.) and is such that it requires 1 volt to increase the current in it at the rate of 1 ampere per second. Capacity on the other hand has the opposite effect to inductance, as it offers infinite resistance to a steady motion or current, but allows alternating current to pass. It is the analogue of a spring which yields to changes of force, but remains stationary for a steady force.

Electrical and magnetic measurements are so closely related that they must be considered together, and we have to deal with magnetic force corresponding to electrostatic force, and magnetic flux corresponding to electric current.

The classification of electrical measuring instruments may be set out in the following table :— that the true ampere should deposit .00111828 gram per second.

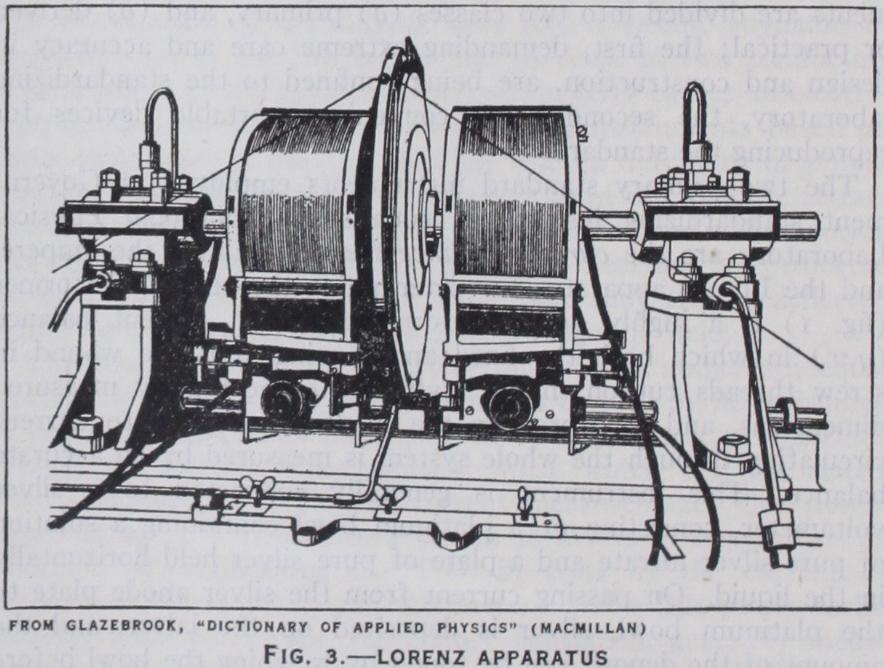

The best primary standard instrument for the determination of the ohm is that originally due to Lorenz in 1873. Essentially it consists of a metal disc (fig. 3) rotated steadily in the magnetic field of a coaxial cylindrical coil through which a current is passed. The arrangement is therefore equivalent to a "Faraday disc" in which the magnet is replaced by the current carrying coil, and an e.m.f. is induced between the centre and edge of the disc. If M is the coefficient of mutual inductance between the coil and disc (the magnetic flux through the disc for unit current in the coil), i the current in the coil, and n the number of revolutions per second of the disc, any radius of the disc cuts across the whole flux Mi in each revolution or Mni lines of force or Maxwells per second. This is, by definition, the e.m.f., E between the centre and edge of the disc. The current passing through the coil is also led through the resistance R to be tested producing a P.D.

The two primary electrical units are those of current (ampere), and resistance (ohm). From these can be derived the unit of potential difference (volt) and any one of these three can be deduced by Ohm's law from the remaining two. Standard instru ments are divided into two classes (a) primary, and (b) derived or practical; the first, demanding extreme care and accuracy in design and construction, are being confined to the standardizing laboratory, the second being convenient portable devices for reproducing the standard.

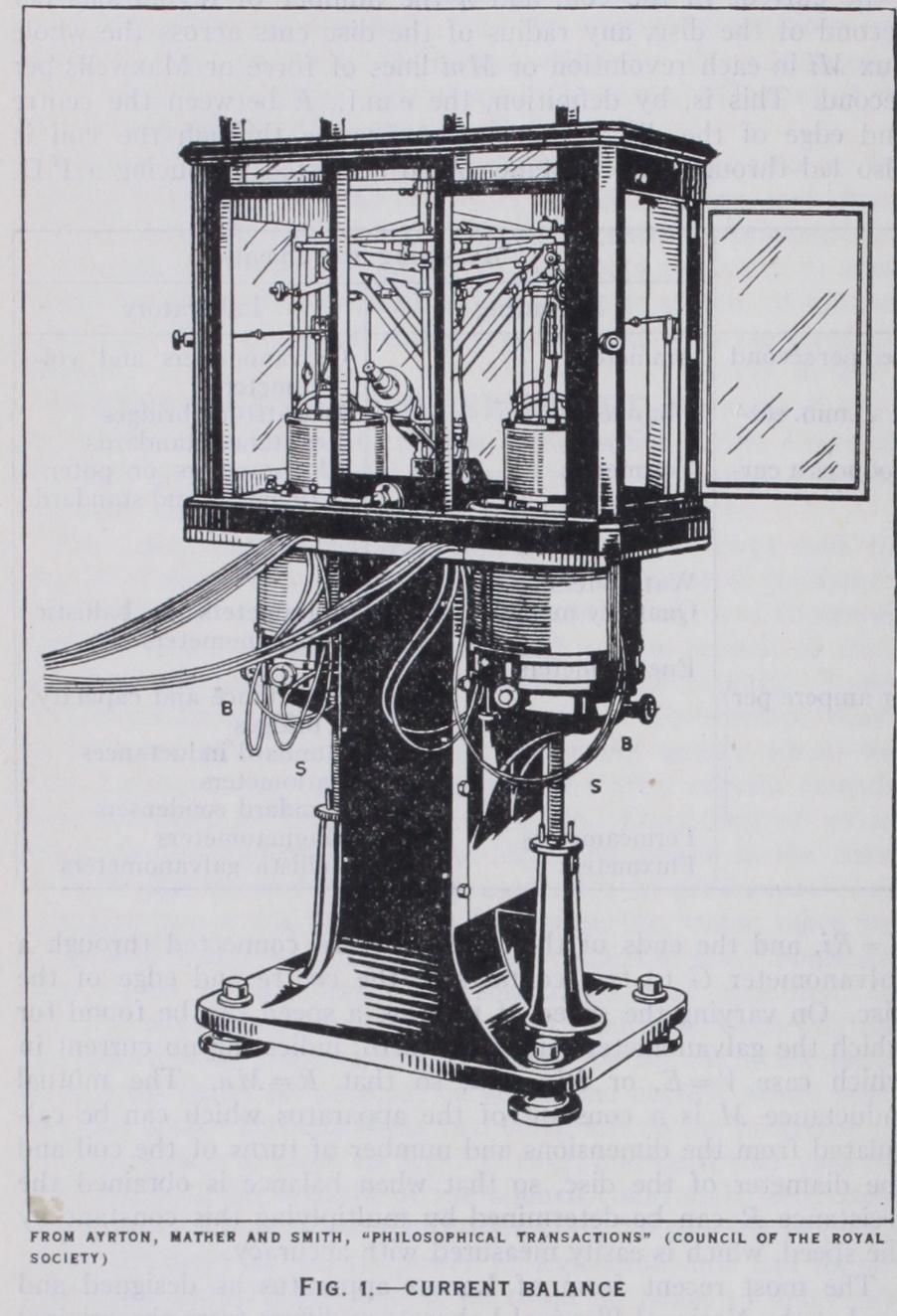

The two primary standard instruments employed at Govern ment standardizing institutions such as the National Physical Laboratory are the current balance for determining the ampere, and the Lorenz apparatus for determining the ohm. The former (fig. 1) is a highly accurate form of Kelvin current balance (q.v.) in which both the fixed and moving coils are wound in screw threads cut on marble cylinders of accurately measured dimensions, and the force on the moving coils due to current circulating through the whole system is measured by an accurate balance. This instrument is generally connected to a silver voltameter, consisting of a platinum bowl containing a solution of pure silver nitrate and a plate of pure silver held horizontally in the liquid. On passing current from the silver anode plate to the platinum bowl, silver is deposited on the latter, and the amount of the deposit can be found by weighing the bowl before and after the deposition. Such a silver voltameter constitutes the derived practical standard of current, and can be set up in any laboratory. The "International ampere" was defined by the Inter national Conference on Electrical Units and Standards in 1908 as "the unvarying electric current, which, when passed through a solution of nitrate of silver in water, in accordance with specifi cation II. attached to these resolutions, deposits silver at the rate of o•o0111800 of a gram per second." The more recent work of Dr. F. E. Smith at the National Physical Laboratory indicates V = Ri, and the ends of this resistance are connected through a galvanometer G to two contacts at the centre and edge of the disc. On varying the speed of the disc a speed can be found for which the galvanometer remains at zero, indicating no current in which case V = E, or Ri = Mni, so that R= Mn. The mutual inductance M is a constant of the apparatus which can be cal culated from the dimensions and number of turns of the coil and the diameter of the disc, so that when balance is obtained the resistance R can be determined by multiplying this constant by the speed, which is easily measured with accuracy.

The most recent form of Lorenz apparatus as designed and used at the National Physical Laboratory differs from the original form principally in having two discs and f our coils wound on marble cylinders so arranged (a) that the system is astatic or unaffected by uniform external magnetic fields such as that of the earth, and (b) that the magnetic field of the coils at the edge of the disc is very low so that small errors in the dimensions have less effect. As the e.m.f.'s in the two discs are in opposite direc tions two contacts only on their edges suffice. The convenience of this apparatus enables standard resistance coils to be standard ized directly, and this appears preferable and likely to be adopted in the future; but at present the practical derived stand ard is the mercury ohm consisting of a glass tube having a bore of I square millimetre in cross section and a length of 106.300 centimetres filled with mercury and at a temperature of o° C. As the cross section of the tube is always determined by filling it with mercury and weighing the latter, the practical definition of the ohm has been modified, and the International ohm is now defined as "the resistance offered to an unvarying electric current by a column of mercury at the temperature of melting ice, 14.4521 grams mass of a constant cross-sectional area and of a length of 106.300 centimetres." The mercury standard ohm is constructed by employing a glass tube having a perfectly uniform bore of i square millimetre cross section (1•129 mm. diameter) which is carefully calibrated for uniformity of cross section along its length by measuring the length of a known small volume of mercury as it is displaced to different positions along the tube. The tube is then cut and care fully ground to the required length and two additional short lengths of it have bulbs blown on their ends and are cemented in exact line on to the ends of the main tube, with very thin sheets of platinum foil between. The foil is then perforated so as to make a continuous uniform tube with contacts at the exact length apart. This tube is filled with pure redistilled mercury and cur rent is passed through it from bulb to bulb, while the P.D. between the platinum contacts can be balanced by a potentiometer and standard cell, thus giving the e.m.f. of the latter in terms of the ampere and ohm. Comparisons between the standard mercury ohm and a standard resistance coil can also be effected by a Kelvin double bridge. Whenever the mercury ohm is in use it is laid horizontally in a trough filled with melting ice. The testing cur rent must be only a small fraction of an ampere to avoid heating the mercury, on account of its somewhat high temperature coeffi cient of resistance (O•o9o% per I ° C) .

The mercury standard ohm is, however, far too difficult to construct to be of practical use, and consequently the standard resistances which are generally employed are in the form of platinum-silver or manganin coils carefully annealed and adjusted and standardized against the mercury standard at a standardizing laboratory. Many standard resistance coils have been devised, such as the original B.A. standard having a platinum-silver coil embedded in paraffin wax, the manganin standards of the Reichsan stalt and the more open forms of Fleming Burstall and Drysdale.

Having defined the ampere and ohm, the International volt is therefore defined as "that electrical pressure which, when steadily applied to a conductor whose resistance is one International ohm, will produce a current of one International ampere." As in the other cases a practical standard is desirable, and this is provided by a standard cell, of which the best and now uni versally used example is the cadmium cell first devised by Dr. Weston in 1892. This cell as now made consists of a small glass vessel of H form (fig. 2) having platinum wires sealed into the bottoms of the main tubes. At the bottom of one of them a small quantity of mercury is placed, and in the other some io% (by weight) cadmium amalgam.

Above the mercury there is a layer of mercurous sulphate and cadmium sulphate pastes, and above the amalgam, a layer of cadmium sulphate crystals. Some cadmium sulphate crystals are also placed over the above pastes, and the remaining space in the two main tubes and the connect ing tube is partly filled with saturated acidic cadmium sul phate solution, the upper ends of the main tubes being her metically sealed. In order to make the cell more portable by reducing the risk of displacing the contents, Dr. F. E. Smith introduced constrictions at the lower part of the tubes, these constrictions preventing move ments of the solid chemicals. The utmost care must be taken over the purity of the materials and cleanliness of the glass vessel and seals, and when the cell is made to the specification its e.m.f. is 1.0183 International volts at 20° C with a temperature coefficient of —0.004% per I ° C. The e.m.f. at any temperature t° C is given by the formula = E20 - 0.000,0406 (t- 20) -o.0OO,000,95(t- O•0OO,OOO,0I (t - The standard cadmium cell properly made up is the most accurate and convenient of all practical electrical standards, and measurements of any P.D. can be conveniently made with it, in conjunction with a potentiometer (q.v.). Another standard cell is the Clark cell. In this cell the cadmium of the Weston cell is replaced by zinc. The negative pole of a Clark cell consists of an amalgam containing io% of zinc; a positive pole, a pure mercury drop, covered with a mercurous sulphate paste; the electrolyte is a solution of zinc sulphate with excess crystals. In all other respects the construction of the Clark cell is similar to the Weston cell. The e.m.f. of the Clark cell at a temperature t° C is given by Watson as These can be divided into two chief classes : (a) Galvanometers or sensitive laboratory instruments for measuring very small cur rents, and (b) ammeters or indicating pointer instruments for large currents. The former are practically exclusively on the electromagnetic principle, while the latter are very diverse in form, and may be either electromagnetic or thermal.

Galvanometers.

These can again be divided into two types, known as the moving needle and moving coil forms respectively. The first are derived from the original discovery of Oersted in 182o that if a conductor is stretched straight over a pivoted magnetic needle and parallel to it, the needle tends to turn at right angles to the conductor when current is flowing through the latter. If the current is re versed the needle turns in the opposite direction. The same re versal effect is produced by mov ing the conductor to the under side of the needle, so that if the conductor is wound into a flat coil encircling the needle, all parts of it tend to deflect the needle in the same direction and the effect is enhanced. This was put into practical form as the first gal vanometer by Schweigger in r 820. Since the deflecting force or torque due to the coil is re sisted by the controlling torque of the earth's magnetic field, it was obvious that the sensitiveness would be increased by reducing the latter or its effect, and Nobili in 1825 therefore introduced the "astatic" needle system in which two equal magnetic needles were mounted with opposite polarities on the same vertical stem, one being inside and the other outside the coil. The system was suspended by a silk thread and pro vided with a light pointer. It was left, however, for Lord Kelvin in 1858 to produce the highly sensitive reflecting type of galvan ometer (fig. 4) which has persisted with minor modifications to this day. He employed an astatic system like Nobili's but with each of the needles inside a coil, the currents in two coils being in opposite directions, so that the deflectional torque was doubled while preserving the small control of the astatic system. The needle system was composed of a thin vertical aluminium wire across which two sets each of three or four short pieces of hardened watch spring were cemented; the two sets being mag netized in opposite directions by being placed between the poles of a powerful electromagnet. Midway between the magnet sys tems, a light concave mirror was cemented to the aluminium stem (sometimes with a thin mica disc behind it to assist in damping the instrument), and the whole system was suspended by a single fibre of cocoon silk cemented to the top of the stem, from the upper bar of a frame. Each of the coils was made in two halves in ebonite cases hinged to the side of this frame so that they could be closed together like a book with the needles in the small space between, and the instrument was therefore generally known as the four coil galvanometer. The mirror was usually exposed through a small space between the upper and lower coil systems. The whole instrument was enclosed in a brass case and glass case on an ebonite base provided with levels and levelling screws, which enabled the base to be accurately levelled and the needles to swing freely in the small space between the coils. On the top of the case was a vertical brass rod on which was mounted a curved permanent magnet on a sleeve which per mitted of its being raised or lowered or turned, and a tangent screw on the rod allowed the final turning to be effected gradually and accurately. This magnet being nearer to the upper than the lower needle system exercised a resultant control on it which could be varied to any extent by raising or lowering the magnet, and the zero could be adjusted by the tangent screw. A good galvanometer of this type wound with coils having a resistance of 6,000 ohms, when adjusted to have a periodic time of 20 sec.gave a deflection of about 8,000 mm. per microamp. on a scale at t metre distance.

Improvements were made in the magnet system by Broca and Paschen and great improvement in sensitiveness and definiteness of zero was secured by employing the quartz fibres invented by Prof. C. V. Boys in 189o, but the most remarkable advance has been made quite recently by Prof. A. V. Hill and Mr. Downing at University college in conjunction with Dr. Daynes of the Cambridge Instrument company. Their galvanometer is similar to the Kelvin four coil instrument above described, but the magnet system has been made still smaller and of the recently discovered cobalt magnet steel (steel with 3 5 % cobalt) which has a much greater intensity of magnetization and permanence than any previ ous form of permanent magnet steel, while the mirror has been reduced to the smallest and thinnest dimensions compatible with optical efficiency. The needle system weighs only o.0045 grams and is suspended by a fine quartz fibre. The coils are also made much smaller so as to obtain the maximum magnetic field for a given resistance. The great obstacle to the general use of the moving magnet galvanometer has been its disturbance by stray variable magnetic fields such as those produced by electrical ma chines or tramways in the vicinity, as no system can be made sufficiently perfectly astatic as to prevent such disturbance, and attempts have been made to shield the galvanometer against such disturbances by enclosing it in heavy bells of soft iron, but with only partial success. Within the last few years however a new nickel-iron alloy (78 nickel to 2 2 iron) known as Permalloy or Mumetal has been introduced, which has a remarkably high permeability in weak magnetic fields, and it was suggested by Drysdale that this would enable an effective magnetic shield to be constructed with only a small thickness of this alloy. Acting on this suggestion Prof. Hill and Mr. Downing made a cylindrical mumetal case for their new type of galvanometer and found that the shielding was so perfect that the galvanometer was unaffected by the starting and stopping of a motor within a few yards of it. This important improvement has enabled the full sensitiveness of the galvanometer to be utilized without difficulty, and a i ohm galvanometer of this type with a periodic time of io sec. has given a deflection equivalent to 5o,000 mm. per microamp. on a scale at a metre distance, or about Soo times the equivalent sensitivity of the Kelvin galvanometer. This achievement may lead to the renewed popularity of the moving needle galvanometer which has been discarded in favour of the moving coil form owing to the freedom of the latter from magnetic disturbance.

Standard Galvanometers.

The instruments so far described have been designed to obtain the highest possible sensitivity, but before the advent of accurate direct-reading ammeters, the tan gent and sine galvanometer, devised by Pouillet in 1837, was in very general use for current measurement. In its simplest form this galvanometer consisted of a short pivoted magnetic needle provided with a long light cross pointer moving over a scale of degrees, and mounted at the centre of a large vertical coil through which the current could be passed. This galvanometer was set up and rotated until the magnetic needle was in the plane of the coil when no current was passing. On making the circuit a magnetic field was produced in the coil perpendicular to the earth's magnetic field and combining with it to produce a resultant field to which the needle deflected. The magnetic field at the centre of a coil of mean radius r and number of turns n when traversed by a current of i amperes is H' = o.2 lrni /r, and if H is the horizontal component of the earth's magnetic field the resultant field will be inclined to it by an angle 0 such that r tan6 = H' H = o•27rni/rH from which i = • tans.

H

If the dimensions of the coil and the horizontal intensity of the earth's field are known, therefore, the tangent galvanometer serves as an ammeter. The value of H in London may be taken as o• 18 but it is liable to variation owing to the proximity of iron objects, so that for accurate work it should be determined in situ.The accuracy of the tangent galvanometer depends on the uni formity of the magnetic field of the coil in the neighbourhood of the needle, and this is only the case over a very small area. For this reason the magnetic needle should be as short as possible, but this is in itself insufficient, and a great improvement was made by Helmholtz who used two equal and parallel coils, separated by a distance equal to the radius of either (fig. 5). With this arrange ment and large coils very perfect uniformity of the field is se cured and the tangent law is very accurately followed. By a slight addition to the tangent galvanometer it can be used for the meas urement of current in another way which has certain advantages. The addition consists of mounting the coils and compass box on a rotatable vertical axis and providing them with a pointer which travels over a scale fixed on the base and divided in degrees. The galvanometer is first set up and turned till its needle is at zero (i.e., in the plane parallel to the coils and to the earth's field, as before) but when the current is switched on and the needle de flects, the whole system is turned round the vertical axis to follow the needle, until the zero of the compass box catches up with it. In this case the field H' of the coils rotates with, and is always perpendicular to them, so that when the zero catches up with the needle the galvanometer has been turned through an angle a such that for a single central coil. For this reason the galvanometer so used is termed a sine galvanometer, and the method has some advan tages as the needle is always in the same position as regards the field of the coils when reading, and the angle of rotation can be more accurately read on the fixed scale used for the coils. Although good tangent galvanometers can usually be used in either manner, the tangent principle has been more generally employed.

Ballistic Galvanometers.

The foregoing galvanometers are used for the detection or measurement of very small steady cur rents, and are therefore preferably damped so as to attain their steady deflection as quickly as possible without oscillating about it. There is another class of galvanometers, however, which are em ployed for measuring the extremely sudden charging or discharg ing of a condenser or inductance, etc., and are termed ballistic galvanometers as being equivalent to the ballistic pendulum for measuring mechanical impulses. If I is the moment of inertia of the magnet system, K the controlling torque per unit angle, T the total torque and a the deflecting torque per unit current we have where is the initial angular velocity of deflection and Q the quantity of electricity which has passed through the coil, provided that it has passed before the system moves appreciably from its zero position. The initial kinetic energy of the system is ZIwo2 and the system will swing until this is converted into potential energy first swing of the galvanometer therefore measures the quantity which has passed, provided that it has all been converted to potential energy against the control and not dissipated in air resistance or damping. For this reason ballistic galvanometers are made as undamped as possible by having somewhat heavy cylindrical magnets to offer the smallest air resistance. In other respects they are similar to other galvanometers.

Moving Coil Galvanometers.

The moving coil galvanom eter arose from the discovery by Ampere, in 182o, that a conductor carrying an electric current tended to move transversely across a magnetic field. (See ELECTRICITY.) The first application of this principle to galvanometers was by Sturgeon in 1836, followed, in 1867, by the Siphon recorder of Lord Kelvin ; but this was used for recording cable signals, and d'Arsonval in 1882 introduced the first reflecting moving coil galvanometer. It consisted of a light rectangular coil of fine wire suspended by the thinnest possible wires between terminals as shown in fig. 6 between the poles of a vertical horseshoe magnet. In order to intensify the magnetic field, a soft iron cylinder was mounted inside the coil without touching it. On passing a current round the coil through the suspensions the coil turned and its movements were indicated by a concave mirror on the coil reflecting a beam of light on to a scale. This type of galvanometer still persists, but Ayrton and Mather improved it in 1890 by making the coil very narrow and discarding the iron core. Various minor improvements have since been introduced, notably by Moll, who employs an electromagnet for his field.

A

good standard Ayrton-Mather type of moving coil galvanom eter has a sensitivity of Boo mm. per microampere at a metre for a resistance of 400 ohms and periodic time of 6 sec., and the Moll galvanometer gives 200 mm. per microampere for a resist ance of 50 ohms and periodic time of 1.3 sec.These sensitivities are far below those of the corresponding moving needle types, but the moving coil galvanometer has the great advantage of being undisturbed by outside magnetic fields, and of having constant sensitivity. On the other hand it has the disadvantage of being heavily overdamped on short circuit, and of being less suitable for very low P.D. measurements such as those on thermocouples, owing to the high resistance of its sus pensions. Up till recently the advantages in most cases heavily outweighed the disadvantages and moving coil galvanometers have consequently been in universal use for all but exceptional cases, but the introduction of the nickel iron magnetic screening by Prof. Hill and Mr. Downing may restore the moving needle instrument to favor.

Duddell Thermo-galvanometer.—Neither of the above types of galvanometer is of any use for alternating currents, and the great need for a sensitive alternating current galvanometer especially for radio measurements, led Duddell in 1904 to adopt the Boys radio-micrometer for this purpose. This instrument con sists in principle of a moving coil galvanometer consisting of a single loop of thin copper wire hung up by a quartz fibre between the poles of a magnet. The lower ends of this loop are soldered to two small vertical bars of bismuth and antimony which are soldered together to a small copper disc at their lower ends to complete the loop and form a thermo-junction. When heat radiation falls on this junction a current flows through the loop and deflects it, and Prof. Boys has used this instrument to meas ure the heat received from stars. Duddell utilized this instrument by fixing a "heater" consisting of a small length of Wollaston wire just under the junction, and the passage of a current through this heater warms the junction and deflects the coil.

Shunts.—The very high sensitiveness of reflecting galvanometers renders it frequently desirable to be able to reduce it by definite fractions so as to be able to measure larger currents, and this is effected by shunting the galvanometer. If a resistance of one ninth of that of the galvanometer is connected across the ter minals, of the total current passes through the resistance and only through the galvanometer, and if the resistance is that of the galvanometer, o or Tom respectively of the total current passes through it. Shunt boxes in which the requi site resistances can be converted by plugs are therefore often employed, but must be made for the particular galvanometers they are to be used with. In 1894, however, Profs. Ayrton and Mather devised a "universal" shunt box which could be used with galvanometers of a fairly wide range of resistances, and these universal shunts are now most commonly employed.

Vibration Galvanometers.—The great extension of bridge or null methods of testing inductance and capacity, etc., has cre ated a demand for highly sensitive galvanometers for alternating currents, comparable with those used for direct-current measure ments. None of the alternating current instruments so far de scribed in any way meet this requirement, and such measure ments have generally been made with telephones as detectors. This, however, confines the measurements to audible frequencies, and there are other objections to their use, so that vibration gal vanometers have come into favour. Such galvanometers are in principle direct current galvanometers of high and variable natural frequency and capable of being "tuned" into resonance with the supply, in which case they produce a vibrating streak of light on the scale and are exceedingly sensitive.

The first practical form of vibration galvanometers was that of Rubens (about 1895), which consisted of a vertical stretched wire carrying a magnet and mirror system and two coils like that of a moving needle galvanometer (q.v.) but non-astatic. By alter ing the tension on the wire and its length by two bridges like those of a monochord, the natural frequency of this system could be brought into unison or resonance with the alternating current in the coils, whereupon the spot of light on the scale broadened out into a long streak. This type was somewhat difficult to "tune." Duddell followed in 191 o by a vibration galvanometer on the lines of his oscillograph (q.v.), but with two long strips, a tension pulley, and two bridges which could be moved by a right and left handed screw. This instrument was remarkably sensitive and covered a frequency range from about 25 to 2,000 ,- per second, but was liable to respond to harmonics on the wave form. In 1911 Drysdale, with the help of Tinsley, devised a vibration galvanometer, primarily for use with his A.C. potentiometer (q.v.), in which the moving system was like that of Rubens, but mounted on a silk fibre. The control was exercised by a large horizontal permanent magnet, the strength of which could be varied by vary ing the distance between its pole pieces and by sliding an armature or "magnetic shunt" along it, so that tuning could be effected without touching the moving system. In 192o he substituted an electromagnet controlled from outside by a battery and rheostat, and this form has since been independently conceived and con structed by the Cambridge Instrument company. Moving coil variable bifilar suspension vibration galvanometers of great sensi tivity have been introduced by Campbell, Gall and others, while a most ingenious single fibre unbalanced instrument has recently been devised by Prof. Moll. All such instruments are extremely sharp in their tuning, and therefore require the frequency of the supply to be kept constant to within about o• i % for their satis factory use.

Oscillographs and String Galvanometers.—The extensive employment of alternating currents of all frequencies from 25 to thousands or millions of cycles per second has caused a great demand for instruments which will give a record of the variation or wave-form of such currents, just as the steam or gas engine indicator records the variations of pressure in the cylinder, and these instruments are known as oscillographs. Prior to their intro duction, such wave forms were somewhat laboriously determined by an instantaneous contact method originally devised by Joubert, and the Hospitalier "Ondograph" based on this principle enables the form of the wave to be automatically traced on paper by a pen. But such methods can only deal with currents which vary in the same manner over some seconds or minutes of time, while the true oscillographs will deal with transient currents which may last only a few hundredths of a second.

Oscillographs are, therefore, galvanometers capable of following rapid fluctuations in the current, and may be either of the moving needle or moving coil type. The inertia of their moving systems must be as low as possible, their natural frequency of oscillation very high, and their damping as nearly as possible critical. For these reasons, the moving system must be as small and light as pos sible. Blondel in 189 i devised the first oscillograph on the moving coil principle, and was closely followed by Duddell who in produced the form of oscillograph which has since been most largely used in this country. In order to diminish the inertia of the coil to a minimum it was reduced to a single loop of fine phosphor bronze strip, and as with even this small inertia a large control was found necessary to obtain the high natural vibra tion frequency aimed at (i o,000 — per sec.) , the two upper ends of this loop were attached to the terminals and the lower portion passed over a small ivory pulley which was pulled downward by a spring, so that both sides of the loop were equally strained nearly up to their elastic limit. The loop with its pulley and terminals was mounted on a brass plate and could be mounted between the poles of a powerful electromagnet, taking the place of the perma nent magnet of the d'Arsonval moving coil galvanometer (q.v.). In order to obtain the strongest possible magnetic field iron pieces were fixed on both sides of and between the strips, and for observ ing the deflections a very small thin rectangular mirror was ce mented across the two strips at their centre. Damping was secured by closing the front by a glass plate and filling the space with oil. On passing current round the loop, one strip moved transversely forward and the other backward in the gaps, so that the mirror was tilted sideways and deflected a beam of light pro jected on to it by an arc lamp. By suitable optical arrangements the reflected beam was focussed on to a photographic plate or film which could be dropped or driven vertically downwards, and the variations of current in the loop were then recorded as a wave on the film.

In order to enable the wave form of a constantly alternating current to be seen or projected on a screen, Duddell also intro duced a second mirror caused to oscillate in a direction perpendic ular to that of the first mirror, by a cam driven by a synchronous motor from the alternating supply mains. The reflected beam from the oscillograph mirror was caused to fall on this second mirror and then on to the screen, causing the wave form of the current to be exhibited as a continuous picture, owing to the persistence of vision.

In nearly all alternating current investigations it is desirable to have simultaneous traces of the variation of the current and the P.D. and for this purpose Duddell employed two loops side by side in the same magnetic field with an iron plate between them to keep the field as strong as possible. One of these loops carried the current to be recorded or was connected across a low resist ance so as to shunt a fraction of the current when it was too large for the strip; while the other was connected, in series with a large non-inductive resistance, across the circuit so that the current through it was proportional to the P.D. at each instant. Each of the loops was provided with mirrors and a third "zero mirror" was arranged between them, so that when the light from the arc fell on them three beams were reflected, giving the P.D. and current waves and the zero axis respectively.

Portable oscillographs on this principle have recently been intro duced by the Westinghouse company in America and the Cam bridge Instrument company in England, the vibrators being made up as separate elements each with its own permanent mag net, and the illumination being produced by a metallic filament lamp which is temporarily overrun during exposure of the film. For high voltages the electrostatic vibrator of Ho and Kato is often substituted for one or more of the vibrators in the outfit.

An ingenious oscillograph on the hot wire principle was devised by J. T. Irwin in 1907, but has not come into general use. In France, M. Dubois has recently devised an oscillograph of the soft iron type in which a tongue of soft iron is caused to vibrate be tween the poles of a permanent magnet, and communicates its motions to the mirror through a strip and pulley.

String Galvanometers.

In 1901 Prof. Einthoven introduced a form of galvanometer which has proved of great value for a large variety of work. It is similar in principle to the moving coil oscillograph but is much more sensitive, although incapable of working at such high frequencies. Instead of the loop a single straight fibre usually of silvered or gilded quartz is employed. This fibre is mounted in the narrow gap between the poles of an elec tromagnet as in the oscillograph, and moves transversely across this gap. As there is no second fibre to which to attach a mirror, the poles of the magnet are bored through so that a small portion of the centre of the fibre can be seen, and a compound microscope with a scale in its eyepiece is mounted in one of these holes and a condenser in the other. The movements of the fibre can there fore be observed and measured through the microscope, or the fibre and scale can be projected on to a screen by an arc lantern directed on to the condenser.The Einthoven galvanometer is, unfortunately, very costly, owing to the difficult construction of its poles and optical observ ing arrangements, and an ingenious attempt at securing its ad vantages with the ordinary simple reflecting mirror device has recently been made by Mijnheer van Dyck of Leyden in his "Torsion String" galvanometer. In this galvanometer the fibre is of the finest silicon bronze wire, and a second thin wire of hard drawn copper lies close to and parallel to it over the portion be tween the magnet poles and is soldered to it at its top and bottom. As the copper wire is of much lower resistance than the central bronze wire, the bulk of the current flowing down the latter is shunted into the copper wire which, therefore, becomes a moving coil with half a turn, and tends to rotate round the central wire, being controlled by the torsion of the latter. As the system is unsymmetrical and therefore unbalanced, a strip of aluminium foil is cemented across the two wires at their centre and a small silvered mirror is cemented on this strip on the opposite side so as to balance the loop, a cleft being made in the corresponding magnet pole to allow of its free rotation. This galvanometer can be used with the ordinary lamp and scale, and with a resistance of Io ohms and periodic time of o.oi sec. is stated to give a deflec tion of 3 mm. per microampere at i metre, which is nearly equiva lent to the sensitivity of the Einthoven galvanometer.

Cathode-ray Oscillographs.

For frequencies -higher than about 2,000 - per second, all the above types of oscillograph are unsuitable, and for higher frequencies up to those employed in radio work the cathode-ray oscillograph has come into use. If a high P.D. is applied between two plates in a very perfectly evacu ated tube, negatively electrified particles or electrons are ejected from the negative plate and travel in straight lines with high velocity across the tube. Such a stream is known as a beam of cathode rays, and when it falls on a phosphorescent screen a bril liant illumination is produced. (See ELECTRICITY: Conduction of in Gases.) A filament may be substituted for the negative plate and gives out electrons when heated by passing a current through it, especially when it is coated with lime or thorium oxide as in "dull emitter" valves. If such a heated filament is enclosed in an evacuated bulb near to two plates each perforated by a fine hole, and a high P.D. is applied between the filament and a ring near the plates, the electrons are driven towards the plates with high velocity, and some of them pass through the holes form ing a very narrow pencil of cathode rays. When such a pencil passes between two plates and a P.D. is applied between them the electrons are attracted towards the positive plate and the beam is deflected in that direction ; while if the plates are the poles of a magnet the electrons tend to move transversely between them like a conductor carrying a current and a deflection in the perpen dicular direction is produced. The most simple oscillograph on this principle is known as the "Braun tube," having been invented by Braun in 1897, and a tube of this kind is now manufactured by the Western Electric company. It is composed of a conical highly evacuated glass bulb having the larger end coated inside with a layer of zinc sulphide or other luminescent material, and a thoriated filament at the smaller end, with a disc with fine per foration as anode. The fine cathode pencil passing through the pinhole, travels between two sets of plates at right angles, so that if two alternating P.D.'s from different parts of a circuit are con nected to them, a trace in the form of a Lissajous figure is gen erally obtained. It is possible to show the hysteresis loop of an iron specimen directly in this manner.The above type of oscillograph has the advantage of being permanently evacuated, but it is only suitable for the observa tion of certain cyclic phenomena, and does not permit of the photo graphic recording of intermittent or transient ones. Prof. Dufour in France and Dr. A. B. Wood in England, have therefore pro duced cathode ray oscillographs in which photographic plates can be inserted, and by using a cold cathode with a P.D. of 50,000 volts the former has obtained records of the wave form of radio transmitters up to over i,000,000 — per second. Such oscil lographs require to be evacuated after the removal of the camera or photographic plate, and not being hermetically sealed, are kept continuously evacuated during use.

Ammeters and Voltmeters.

As their names imply these in struments are respectively intended for directly measuring electric currents in amperes, and potential differences in volts, and they may conveniently be considered together as they are often similar in construction. For the majority of purposes these instruments are of the electromagnetic type, but thermal or "hot wire" in struments are used for alternating currents especially for those of high frequency such as are employed in radio working. The electromagnetic instruments are however of very diverse types. There are first (a) the moving magnet and (b) moving coil types corresponding to galvanometers; but in addition there are moving soft-iron dynamometer, and induction instruments, all of which can be used with alternating currents, the last being for alter nating currents only.

Electromagnetic Instruments.

(a) Moving Magnet Type.— The first direct reading ammeters and voltmeters introduced by Ayrton and Perry in 1879 were of this type. It consisted of a small magnetic needle on a short spindle between two pivots, and provided with an aluminium pointer. A small coil encircled the needle, and the whole system was fixed between the poles of a powerful permanent magnet, so that extraneous fields had little influence. The instrument has some similarity to the tangent galvanometer in principle, but the coil is small, and the earth's field is replaced by that of the horseshoe magnet. The large con trol given by such a magnet is an advantage in this case where sensitivity is ample, as it increases the rapidity of the readings. An interesting feature of this type of instrument was the winding of the coil with ten separate insulated strands which could be connected in series or parallel thus giving two ranges of a ten fold ratio of current. The same type of instrument could be used as a voltmeter by winding the coil with fine copper wire and connecting it in series with a high resistance coil of German silver and other wire of low temperature coefficient so that its total resistance was sensibly constant, and the current flowing through it was proportional to the P.D. applied to the terminals of the instrument. This device can be employed with almost any type of ammeter. The moving magnet type of ammeter has gone out of use for many years owing to its cost, but it has recently been revised in an interesting form by the Westinghouse company, who substitute a second horseshoe of nickel iron with its poles at right angles to those of the permanent magnet. This horseshoe projects through the back of the case, and the conductor carrying the current is simply threaded through it, so that the conductor need not be divided and the instrument has no terminals.(b) Moving Coil Permanent-magnet Indicating Instruments were introduced by Dr. Weston in 1888 and were similar to the d'Arsonval galvanometer, except that the coil was pivoted and controlled by spiral springs carrying the current, and a pointer was substituted for the mirror. This type has been developed into the most accurate of all direct current indicating instruments in the Weston and other laboratory standards, and has assumed many different forms, notably the "Cirscale" instruments of Messrs. Record, in which the poles are so arranged that the coil and pointer can rotate through nearly 2 7o°. As the thin control springs can only carry a very small current (7 5 milliamperes is the usual maximum) the instrument can be used as a voltmeter by connecting a high resistance in series with the coil, but if it is to be employed for measuring larger currents, "shunts" are provided consisting of manganin or constantan strips having two terminals through which the current is passed, and two other terminals to which the instrument is connected, so that it acts as a low reading voltmeter measuring the current by the P.D. across the shunt. A single moving coil instrument with a set of series resistances and shunts will therefore serve for a very wide range of P.D. and current measurements, and portable "test sets" are commonly made covering the range from about o.i to 600 or more volts or amperes.

Moving Soft-iron Instruments.

These are the most simple and inexpensive ammeters and voltmeters and can be used both for direct and alternating current measurements. If a current is passed through a coil, a piece of soft iron will be sucked into it, and if a suitably shaped piece of soft iron is pivoted and provided with a pointer a very useful form of ammeter can be made. If the coil is wound with fine wire and a series resistance added the instrument becomes a voltmeter. The first instruments of this type were introduced by Ayrton and Perry in 1884 and others by Lord Kelvin, Schukert, Siemens, Nalder, Weston, etc. The last two are on what is called the repulsion principle, having two soft iron rods lying parallel to one another and to the axis of the coil. When the current flows these two rods are magnetized with the same polarities and consequently repel one another like the pith balls of an electroscope, so that if one is fixed and the other at tached to a pivoted arm provided with a pointer, a deflection is produced. This last construction has some advantages over the others, as the two pieces of iron lie close together when the cur rent is small, and are farther apart for large currents. For a given distance apart the force between the irons is proportional to the square of the current, so that it is very small for small currents, but this is partially compensated by their greater prox imity, and the torque is consequently much more nearly propor tional to the current and the instrument has a larger useful range than the single iron form. The same result may be obtained in the attraction forms by shaping the iron, but this requires careful experiment.The moving soft-iron instruments are of great value in principle as they are not only simple in construction but are equally suitable for direct or alternating currents, as they obviously indicate the square root of mean square (R.M.S., or effective) current; while the moving coil permanent magnet instruments will only read on continuous current. Until quite recently, however, this valuable property was not taken full advantage of, owing to certain appar ently inherent defects in the type. The first is the want of pro portionality of magnetization in the iron to the current, and the hysteresis in the iron, which causes the instrument to read higher for a certain current when it has fallen from a higher value, than when it has risen from a lower one. In addition there is the high inductance of the coil with its iron cores, which causes a volt meter of this type to read lower for the same P.D. as the fre quency is increased and prevents the use of shunts for ammeters; and lastly, the demagnetizing effect of induced eddy currents in the iron and any metal parts close to it. All these errors have mili tated against the adoption of this type as a universal instrument, although A.C. ammeters and voltmeters for a single frequency have been largely employed.

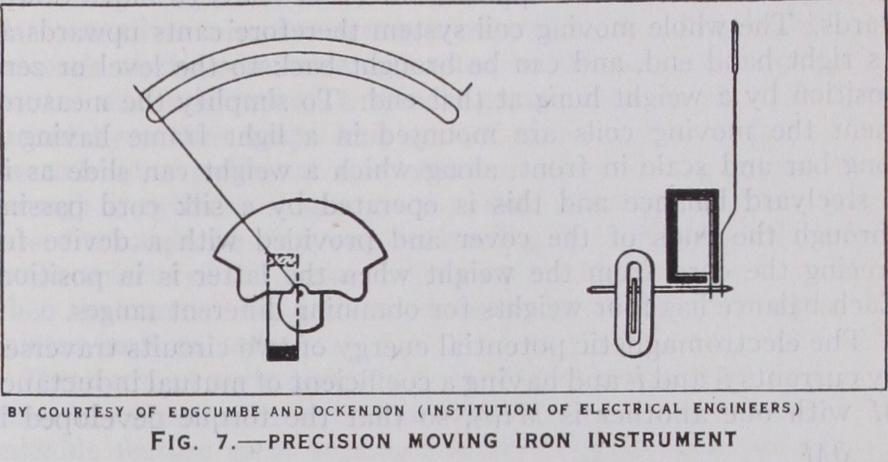

Within the last few years, however, a great advance has been made notably by the substitution of Permalloy or Mumetal for the moving iron, which has resulted in the practical elimination of wave form and hysteresis errors, and by making the coil as small and flat as possible so as to allow of a thin plate of this alloy to be attracted into it, thus greatly reducing the inductance and eddy-current errors. It was pointed out by Drysdale in 1924 that since the electromagnetic energy in an inductive coil E = where L is its inductance and i the current passing through it, the torque T = = Zit aL , so that the instrument always oper ae ae ated by the increase of its inductance from at zero to at its highest reading; and he proposed the term "electromagnetic efficiency" for the fraction On examination of existing instruments it was found that this efficiency was only 1 or 2% or less, so that of the total inductance about 99% was useless and noxious, and only about 1 % useful in deflecting the instru ment. Acting on this principle Col. Edgcumbe and Mr. Ockenden devised an ammeter on the lines above indicated (fig. 7), with the result of obtaining practically negligible hysteresis and eddy current errors and of increasing the electromagnetic efficiency to about 30%, and the current range to 15 or 20 fold. This has enabled it to be employed with shunts or series resistances like the moving coil instruments, either for direct current or with alter nating currents up to 200 periods per second. It is claimed, and with apparent justice, that such instruments need not be inferior in accuracy to moving coil or other high-grade instruments. By using one fixed and two independently moving irons, Record has produced a moving iron instrument having a scale covering about 270°.

Dynamometer Instruments.

These form an important class of current measuring instruments as they are equally suitable for direct or alternating currents, and can be made either as standard, sub-standard or deflectional indicating instruments. They depend fundamentally on Ampere's discovery (1820) that parallel conductors carrying rents attract each other if the currents are in the same direction or repel each other if they are in opposite directions. In Weber produced a simple form of "electrodynamometer" on this principle, but the first practical measuring instruments appeared in 1883, when Kelvin and Joule devised the standard current weigher or balance, and Siemens the substandard dynamometer.The principle of the Kelvin balance is shown in fig. 8. The instrument consists essentially of six horizontal coils, four of which are fixed (F) and two movable (M), and the current to be measured traverses the whole of the coils in series. In order to allow the two movable coils to swing freely between the fixed ones, they are suspended by a large number of straight fine wires forming straight straps or ligaments. The current passes round the coils as shown by the arrows, and it will be seen that on the right hand side the current in the centre moving coil is in the same direction as that in the upper and in the opposite direction to that in the lower of the fixed coils. The moving coil is therefore attracted to the upper and repelled from the lower coil and tends to move upwards, while the left hand moving coil in which the current circulates in the opposite direction tends to move down wards. The whole moving coil system therefore cants upwards at its right hand end, and can be brought back to the level or zero position by a weight hung at that end. To simplify the measure ment the moving coils are mounted in a light frame having a long bar and scale in front, along which a weight can slide as in a steelyard balance and this is operated by a silk cord passing through the ends of the cover and provided with a device for freeing the cord from the weight when the latter is in position. Each balance has four weights for obtaining different ranges.

The electromagnetic potential energy of two circuits traversed by currents and and having a coefficient of mutual inductance M with one another is so that the torque developed is In the Kelvin balance the two circuits are in series so ae that i, and the torque is i2 or is proportional to the ae square of the current, so that the instrument serves equally for direct or alternating current measurements. Various sizes of these balances, "Centiampere," "Ampere," "Deka-Ampere," "Hector-Ampere," and "Kilo-Ampere" have been constructed, but the latter, on account of their large conductors, are not ac curate for high frequency currents owing to eddy currents, although the conductors are stranded or laminated.

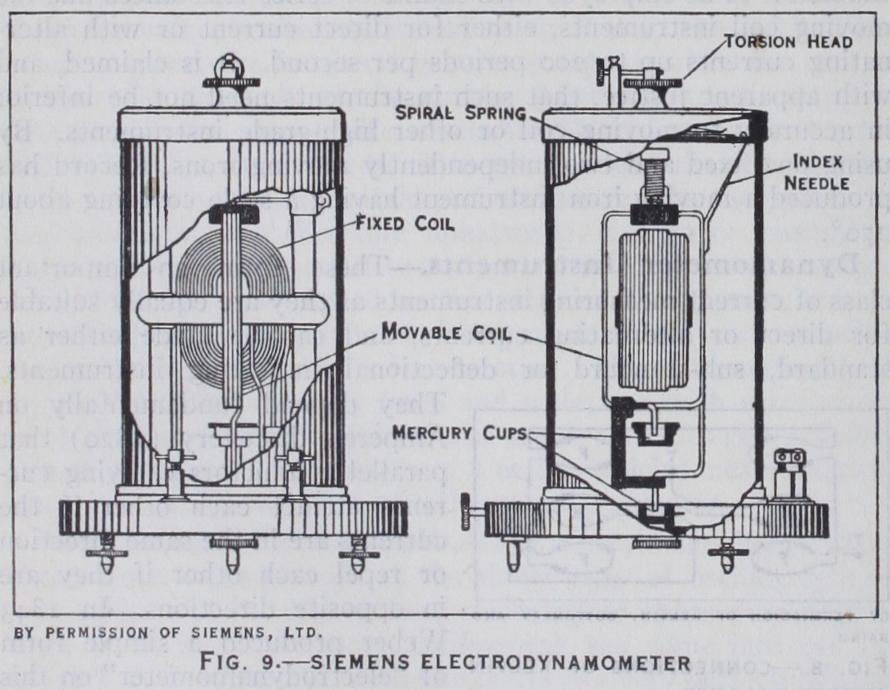

The Siemens dynamometer (fig. 9) was for many years the most useful form of substandard instrument for both direct and alternating current testing. It consists essentially of two coils at right angles, the inner (F) having a large number of turns and being fixed with its axis horizontal on a wooden frame, and the outer (D) in the form of a loop encircling the fixed coil and suspended by a silk thread, with its two ends brought out at the bottom to dip into two mercury cups MM. On the top of the frame a circular scale is fixed, with a torsion head T and pointer, a cylindrical spring S encircling the suspension being mounted between the torsion head and the top of the coil. The current circulates round both coils in series and causes the swinging coil to turn, whereupon the torsion head is turned until the torsion of the spring brings the coil back to its zero position as indicated by a pointer I fixed to the top of the coil. The current then= KVD, where K is the constant of the instrument and D the angle turned by the torsion head. In order to increase the range of the instrument, the fixed coil is generally made of two portions with different thicknesses and number of turns of wire, and either of these can be connected in series with the moving coil.

Both of the above instruments are of the standard type in which it is necessary always to bring the coils into the same position, in order that the theoretical square law shall be followed. But deflectional direct indicating instruments can be made by simply providing the moving coil with a pointer and control spring, in which case they are equivalent to permanent magnet moving coil instruments in which the magnet is replaced by the fixed coil. In 1890 the first instrument of this type was introduced by Dr. Weston as a dynamometer voltmeter, the fixed and moving coils being circular, wound with fine wire, and connected in series through the spiral springs which provided the control. A high non-inductive resistance was connected in series with the combina tion and the instrument was graduated as a direct reading volt meter. Additional ranges were provided by extra series resistances. Dynamometer ammeters have also been constructed by making the fixed coil of thicker wire and connecting the moving coil in series with a small non-inductive resistance across the terminals of the fixed coil or an additional shunt, but it is difficult to elimi nate inductive errors sufficiently in such instruments.

The most valuable application of the dynamometer principle is to standard and deflectional wattmeters, and to energy meters, which will be described later.

Induction Instruments.

These instruments may be de scribed as dynamometer instruments in which current is led into the moving system by induction or transformer action instead of by conduction through springs or ligaments, and they can therefore only be used for alternating currents. They were initi ated by Prof. Ferraris, the pioneer of polyphase working, in 1885, but have assumed many different forms, and have been adapted for many different measurements.Induction instruments may be divided into three main classes, (a) repulsion, (b) shaded pole and (c) double pole instruments. The first depend upon the repulsion effect first discovered by Prof. Elihu Thomson, that a metal disc or ring is repelled from an electromagnet excited by alternating current. The explanation is that the magnet induces an e.m.f. in the disc or ring in quadra ture with the magnetic field, which consequently produces eddy currents in it. If these currents were in phase with the induced e.m.f. they would also be in quadrature with the magnetic field and there would be no resultant force, but owing to the inductance and low resistance of the disc they lag behind the e.m.f. and be come somewhat in antiphase with the magnetic field, producing a resultant repulsion.

The simplest application of this principle to ammeters is that of the Westinghouse company, in which the moving element con sists simply of a thin aluminium or copper disc on a pivoted spindle perpendicular to its plane. The edge of this disc is how ever cut in the form of a cam and can turn in the gap of a' laminated electromagnet through the coil of which the alternat ing current to be measured is passed. A control spring and pointer is attached to the spindle and when the system is at zero the whole of the pole face is covered by the disc. When the current is passed the repulsion effect causes the disc to turn so that less of the pole face is covered by the disc, and by suitably shaping the edge a long and fairly even scale can be obtained. In order to damp the swinging of the disc, a permanent magnet is mounted on the other side of it, which retards its movements by the eddy currents induced.

The shaded pole type of instrument is next in simplicity of construction, but is best understood by first describing the double pole form. If two laminated electromagnets A and B are fixed close together and act on a single circular disc, the alternating magnetism of A induces currents in the disc part of which pass through the gap of magnet B, so that the disc behaves as a mov ing coil carrying current derived from A and traversing the mag netic field of B, and thus producing a torque. But, reciprocally, the currents induced in the disc by magnet B traverse the field of A, and it is fairly obvious from the symmetry of the arrange ment that if the two magnetic fields vary in the same phase, there will be no resultant torque, as there is no reason why it should move from A to B rather than from B to A. But if the magnetic field in B lags in phase behind that of A there is a resultant torque from A to B and this torque is proportional to sin4) where and are the currents in the two coils and 4 the angle of phase different between the fields. This difference in phase may be secured in several ways, e.g., by shunting one of the mag nets or connecting it in series with a condenser, or by supplying the currents from different parts of the circuit, as will be described under wattmeters and energy meters.

The most simple application of this principle however to cur rent measuring instruments is by "shading" part of a single pole (fig. 1o). If a single laminated electromagnet has a cleft in its pole and a thick copper ring C encircles one part of it, B as shown, the eddy currents induced in this ring by the magnet react on its field and cause the magnet ism of the part of the pole en circled by the ring, or "shaded" portion, to lag behind that of the remainder or unshaded portion A. Thus the single magnet be haves like the two magnets above referred to, and a pivoted disc arranged in the field of this magnet tends to turn from A to B. By adding a spring and pointer and damping magnet, a useful form of ammeter can be produced, and the scale can be of any length up to nearly 36o°. The theory of induction instruments is very complex, and they are liable to many errors, but by careful design they may be made very useful and accurate instruments.

Current and P.D. Transformers.—A great difficulty with al ternating current instruments is their lack of range, as since the forces in them are generally proportional to the square of the current, a reduction of the current to one-third reduces the force to one-ninth of its maximum value, and many instruments there fore only have about a fourfold useful range. On the other hand, the range of currents and voltages to be measured is enormous, from fractions to tens of thousands of amperes or volts. With nearly all such instruments shunts are useless owing to the in duction errors they introduce, and for many years past the prac tice of employing transformers has been adopted. If a trans former is made with a good well-laminated magnetic circuit and two coils wound close together, one of which is short circuited through an ammeter, while the other has the alternating current to be measured passed through it, the current induced in the secondary coil will be proportional to that in the primary coil and approximately in the ratio of the number of turns in the coils. For example if an alternating current of 5,000 amperes is to be measured, a transformer may be made with a single bar or turn carrying this current, and a secondary coil of r,000 turns which is connected to a 5 ampere ammeter. This device has the further important advantage of isolating the ammeter completely from the main circuit, which may be at a dangerously high poten tial on modern supply circuits. In like manner, if a transformer is wound with two coils of fine wire, one having ioo times as many turns as the other, and an alternating P.D. of io,000 volts is applied to the coil having the larger number of turns, it will in duce zoo volts in the other coil which can be measured in an ordinary voltmeter, without connecting it to the high voltage cir cuit. By the use of the Mumetal for the iron of the transformers, Col. Edgcumbe and Mr. Ockenden have recently made instru ment transformers of very high precision.

Thermal or Hot Wire Instruments.--These instruments, as has been mentioned, depend upon the heating effect of a cur rent passing through a conductor, and are equally suitable for direct or alternating current measurement. The power developed in a circuit having a resistance r ohms and carrying a current i amperes is yip watts, and produces a heating effect of 0.24 ri calories per second. Since the heating is proportional to the square of the current, it is the same for either direction of flow, and the average heating with alternating current is proportional to the mean square of the current.

Hot wire instruments are of two types (a) expansion and (b) thermo-junction. In the former the linear expansion of the wire caused by the heating is utilized ; in the latter the heat is com municated to a thermo junction, which is connected to a milli voltmeter.

Until the last few years hot wire instruments have all been on the expansion principle, the earliest form being the voltmeter, devised by Maj. Cardew in 1883. In this instrument a long thin platinum-silver wire was strung over pulleys in a brass tube, and the ends of the wire were connected to the terminals; while the pointer was mounted on a spindle geared to a pulley which was turned by a thin strip. One end of this strip was attached to the axle of a pulley at the centre of the wire and the other, through a cylindrical spring, to a fixed support. When current passed through the wire, causing heating and expansion, it yielded to the tension of the spring and caused the pointer to turn; while when the current was broken, the wire contracted and pulled the pointer back to zero.

This form of voltmeter was very clumsy and inconvenient and wasteful of power, but its freedom from inductance was such a valuable feature as to stimulate improvements, and modern hot wire instruments have been constructed on the "sag" principle originally suggested by Ayrton and Perry, but first carried into execution by Hartmann and Braun. In these instruments the heated wire is straight and only a few inches long, and both ends are fixed; but the strip attached to the pointer and antagonistic spring is attached near the centre of the wire, so that the tension tends to pull it to one side or cause it to sag. A very small in crease of the length of the wire will greatly increase this sag, and approximately as the square root of the extension, so that not only does this method give a large magnification, but it helps to compensate for the natural square law of the expansion, and gives a more uniform scale. The magnification secured by a sin gle application of this principle was, however, hardly sufficient, so that in the Hartmann and Braun instrument (fig. r z) the transverse wire S2 was again treated as a sagging wire and the strip actuating the pointer was attached to its centre, making it what may be called a double-sag instrument. A thin aluminium sector passing between the poles of a permanent magnet served to damp the indication. An average instrument of this type takes about 0.2 ampere at its maximum reading and has a resistance of about 17 ohms, implying a power consumption of 0.7 watt in the wire; but when used as a voltmeter for 120 volts it consumes a total of 24 watts, as compared with only 4 or 5 watts for moving iron voltmeters. To adapt this type of instrument as an am meter, one method is to lead the current in and out of the wire at several points by means of very thin and flexible strips and S3. If the current is led in at the centre of the wire and out by its two ends the range is doubled, and so on. For still heavier currents a large number of exactly similar wires can be con nected in parallel, and shunts can also be employed.

Expansion instruments have done valuable service for alter nating current measurements, es pecially at high frequencies, but they have never attained the ac curacy of good electromagnetic instruments, owing to the changes of zero due to expansion of the supports. Various methods of compensation have been devised with good results, but none have been completely satisfactory under all conditions. Another ob jection to them is their very small overload capacity, as the wire must be raised to a high temperature to obtain sufficient expansion. Doubling the current produces four times the heating effect. Fusing of the working wire involves remounting and recalibration of the instrument.

The thermo-junction instruments which were first put into commercial form by the Weston company are much more con venient than the expansion type, and are probably destined to supersede it, as they only involve a simple attachment to a stand and type of moving coil millivoltmeter. For many years before their advent a very common laboratory device for measuring high frequency currents was the `'crossed thermo-junction," consist ing of two fine wires, one of copper and the other of constantan (nickel-copper alloy) crossed at right angles and soldered together at their crossing point. Current was passed from one end of the copper wire through the junction to one end of the constantan wire, causing the junction to be heated; while the other two ends were connected to a moving coil galvanometer. As the thermo e.m.f. of such a junction is about 4o microvolts per degree, a rise of 300° C produces an e.m.f. of 12 millivolts, which will produce a reasonable deflection on a moving-coil pointer instrument. The Weston company therefore employed one of their standard forms of moving coil millivoltmeter with a recess in the base in which a strip carrying a short heating wire and thermo-junction was clamped. This can be easily replaced if burnt out.

Dr. Moll has recently greatly improved on this device by what he calls his "thermo-converter," having a fairly long heating wire threaded through about 5o insulated thermo junctions. By this means he secures a thermo e.m.f. of 8.5 millivolts for 16 milli amperes in the heating wire and a rise of temperature of only To° C, which allows a very ample margin for overload.

Wattmeters

are intended for the direct measurement of electrical power, especially in alternating current circuits. As the power expended in, or taken from, an electrical circuit, in watts, is equal to the product of the P.D. in volts and current in amperes, it can be measured on direct-current circuits by a voltmeter and ammeter. But with alternating or pulsating currents this is not the case, and a special instrument is needed in which the torque is pro portional to the product of the P.D. and current at each instant, and indicates the mean value. Such instruments are termed watt meters and are essential for all alternating current power meas urements. They may be either electromagnetic, electrostatic, or thermal, but practically all indi cating wattmeters are on the elec tromagnetic principle, and most are of the dynamometer type. It has been stated above that if two current carrying coils are near together, the force or deflecting torque between them is propor tional to the product of the strengths of the two currents, so that if one of the coils carries the current in the circuit by being connected in series with it, and the other is wound with fine wire and shunted across the circuit like a voltmeter, the current in the second coil is proportional to the P.D. if its resistance is con stant, and the force or torque between the coils is proportional to the product of the P.D. and current, i.e., to the power in the circuit, at each instant. If the shunt coil is suspended inside the series coil and provided with a pointer and control spring the deflection is proportional to the average power, as the inertia of the coil prevents it from following the rapid variations of the alternating currents.The principle of the electrodynamometer wattmeter was first put forward by Ayrton and Perry in 1881, and was adopted by Kelvin in his Watt balance, and by Siemens in 1884, the moving coils of the Kelvin balance or Siemen's dynamometer being made of fine wire and in series with non-inductive resistances. Unfortunately, Ayrton and Perry, from a theoretical considera tion of its behaviour on alternating current circuits at various power factors, were led to the conclusion that large and indeter minate errors would appear at low power factors (i.e., large angles of lag or lead of the current), and as this was apparently con firmed by some tests with a defectively constructed wattmeter of Swinburne's, the dynamometer wattmeter fell into disrepute. It was not till Igor, when Drysdale gave a different treatment of the errors, and showed that they could be made perfectly deter minate, and be reduced to inappreciable proportions by suitable design, that confidence was restored. He showed that if the ratio of resistance to inductance of the shunt circuit was over 300 ohms per millihenry, and if the instrument was kept free from metal other than the carefully stranded coils, no readable error could exist, and produced a wattmeter in which these require ments were fulfilled. A little later Duddell and Mather produced an astatic wattmeter on very similar lines. Both of these instru ments were of the torsional or standard type, and their current ranges could be varied by combining the strands of the current coils in various series and parallel combinations, while the P.D. range could be extended to almost any extent by series resistances.

Deflectional direct reading dynamometer wattmeters have been devised by Kelvin, Heap, Hartmann and Braun, the Weston In strument Company, and many others, and are similar to the cor responding forms of dynamometer voltmeters, but with the fixed coils wound with thick wire to carry the current. The Weston wattmeter has a circular formerless moving coil fixed on a pivoted spindle with two spiral springs serving as control and leading-in wires, and a light truss-form pointer at the upper end, and damp ing vanes at the lower end. Two fixed current coils are held in a frame of high resistance metal alloy to reduce eddy currents, and the moving coil swings inside them over an arc of about 90°.

The quadrant electrometer can also be used as a wattmeter since the deflection is proportional to the product of the P.D. between the quadrants and of that between the needle and the mean of the quadrants or to (V — Vl+ V2) where V, 2 VI and V2 are the potentials of the needles and of the two quadrants respectively. If a non-inductive resistance r is con nected across' the quadrants and the current i is passed through it V2 - V, = ri or is proportional to the current, and if the P.D. is applied between the midpoint of this resistance and the needle, the deflection is proportional to the product of the current and P.D., i.e., to the power. This electrostatic method was also de vised by Ayrton and Perry, and was developed about 1 goo by Addenbrook and later by Paterson and Rayner at the National Physical Laboratory, where it is used as the standard for check ing commercial wattmeters. It is not, however, suitable for port able or switchboard instruments owing to the small forces avail able. Thermal or hot wire wattmeters have also been devised by Field, Irwin, and others but have not come into general use.

The induction type of instrument however lends itself excel lently to switchboard wattmeters of moderate accuracy owing to the simplicity and robustness of its construction. In discussing the double magnet induction ammeter (q.v.) it is stated that the torque on the disc is proportional to sine where and are the currents in the coils and 4) the angle of phase difference between them. If one of the magnets is wound with thick wire and connected in series with the circuit like an ammeter, and the other is wound with fine wire and connected across the mains like a voltmeter, the current in the latter coil is proportional to the P.D. across the mains but nearly in quadrature with it owing to its high inductance so that sin4 = cose j where 0 is the phase difference between the circuit P.D. and current. The torque is therefore proportional to Vi cose i.e., to the power. Certain compensations are necessary, as the resistance of the shunt coil destroys the perfect quadrature, but they can be effected with sufficient accuracy, and if the disc is provided with a damping magnet and control spring a long scale indicating wattmeter with proportional scale is produced. A large number of such watt meters have been devised and Edgcumbe and Ockenden, and Lip man have recently carried the design to great perfection. On the other hand if the control spring is removed, the torque developed by the damping magnet is proportional to the speed, and as it is also proportional to the power, the disc will rotate at a uniform speed proportional to the power. The amount of the rotation in a given time will thus be proportional to the time integral of the power, or to the total energy supplied or absorbed. The instru ment then becomes an energy supply meter, and the bulk of the supply meters used on A.C. circuits to-day are on this principle.

Polyphase iVattreters.—About 1896 Dobrowolski pointed out that the power either on a two phase supply or on a three phase three wire supply could be ob tained by using two wattmeters and adding their readings to gether. Following on this, Drys dale in 19OI produced a double wattmeter with two similar mov ing coils at right angles, one be low the other, on the same spindle, and with two similar sets of stranded fixed coils also at right angles, so that the indica tions of the two systems were me chanically added together on the spindle and could be balanced by torsion in the usual manner. Deflectional direct reading polyphase wattmeters have since been made on this principle by the Weston Instrument company, and many others. The induction wattmeter and energy meter can similarly be adapted for polyphase supplies, by using two sets of series and shunt magnets on opposite sides of the same disc.

Electric Supply Meters.