English Furniture

ENGLISH FURNITURE English furniture has developed in the course of many years from a few primitive types to highly specialized varieties ; it has evolved gradually with the progress of civilization. So little survives from mediaeval times that information must be sought in contemporary references, supplemented by representations in illuminated manuscripts. Most of these miniatures are of foreign origin; but they are reliable evidence, for the governing classes were Continental in their habits and the equipment of their homes. The furniture made for them was strongly influenced in form and detail by Gothic architecture, and was freely embellished with colour and gilding. English oak was the chief material, but softer woods were also used.

The furniture usually found in important houses consisted of beds, chests, cupboards, tables and stools. These objects are the basic types from which the whole evolution can be traced. Wills and inventories prove that draped bedsteads were treasured posses sions of mediaeval householders, prized not for the rough frame work but for their magnificent woven and embroidered hangings. These draperies consisted of a celure (back), tester (canopy), curtains and valances, and on them were worked scenes from the chase and many fanciful devices. Such beds were placed in the principal living rooms, and served as couches in the daytime. Chests were almost the only receptacles for valuables. They sur vive in large numbers, many 13th century examples being pre served in churches. The fronts, formed of stout planks, are pegged into wide uprights, plain, or carved with grotesque monsters. Later specimens are sometimes carved with arcades of Gothic tracery, scriptural incidents or mythological subjects. Large travelling chests, called "standards," were bound with iron and covered with leather. At the ends were iron handles through which ropes could be passed to facilitate transport. The guild of cofferers already existed in Edward III.'s reign, but could not prevent the importation of Danzig chests and others of overseas work. On a dresser in the hall flagons and cups were displayed. It was an open framework of shelves with a projecting lower portion, sometimes enclosed by doors. Side-tables, used for serving meals, were in the form of a chest mounted on legs, the panels pierced with Gothic tracery. What are now termed cupboards were known as ambries. Existing specimens are of massive construction with cross divisions and foliated iron hinges. Until the close of the middle ages chairs were lofty, throne-like structures, few in number and regarded as symbols of authority. The ordinary seats were chests and stools with benches sometimes fixed to the walls. Mediaeval dining tables were of trestle construction, boards of oak or elm resting on a series of central supports. They had removable tops and could be stored away of ter meals. Two examples still remain at Pens hurst Place, the tops, nearly Soft. long, being supported on carved trestles with cruciform feet. Towards the end of the i 5th century panelled framing, or joinery with mortice and tenon, replaced the primitive method of construction in which planks split or sawn from the log were roughly put together with pegs. At this period panels were often carved with the linen-fold pattern, so called from its resemblance to linen arranged in upright folds.

Tudor.

In the Tudor period the character of domestic fur niture was gradually transformed by Renaissance influence, carved profile heads, dolphins and foliated scrolls appearing on struc tures which at first remained Gothic in design. Henry VIII. em ployed Italian craftsmen for the equipment of his new palaces, and their works were imitated by native craftsmen with less delicacy and finish. Walnut, more readily carved than oak, was extensively used, and, though much of this furniture was imported, there are undoubted English examples. Under Elizabeth inlay consisting of arabesque or chequer patterns in coloured woods came into vogue as decoration. There was a notable increase in domestic comfort. Harrison about ' 587 reported that costly furni ture had descended "even unto the inferior artificers and manie farmers." By this time the style had emerged from foreign tute lage and assumed a character distinctively English. It is coarse and vigorous, prodigal of material and floridly enriched. The round arch figures prominently with corbels and grotesque term inals ; foliated strap-work fills the decorative areas, while nothing is more characteristic of Elizabethan furniture than vase and melon-shaped supports of prodigious girth profusely carved. In the matter of new types there was little innovation, but capacious presses were provided for clothes and mirrors of glass in highly decorated frames were becoming known at court. Chairs were more abundant. They had panelled backs and joined frames and could be readily moved ; in some the woodwork was hidden by rich fabrics. Beds were now constructed of wood throughout, a panelled back and posts supporting a ponderous tester. Joined tables with "draw," or extending, tops ousted the trestle variety; while court cupboards and buffets laden with plate adorned every well-appointed hall.

The Stuart Period.

This increase in domestic comfort con tinued until the outbreak of the Civil War. From James I.'s reign padded and upholstered seats survive, and at Knole may be seen chairs of X pattern covered with silks and embroidered velvets. A very remarkable specimen, in which Charles I. is said to have sat during his trial, has lately been acquired by the Victoria and Albert museum. Such chairs show Continental in fluence, but the main output was insular and traditional. The style gradually lost its rude vigour. Structural members dwindle in scale, and fanciful carving degenerates into stock patterns, eked out with applied bosses and spindles. The furniture of the Protectorate is, for the most part, severe and angular.After the Restoration there was a striking change. The exiled court on its return introduced French fashions, and austerity gave place to lavish display. Furniture became lighter, more highly finished, and better adapted to varying needs. Walnut was the favourite material. Joinery developed into accomplished craftsmanship and new processes appeared, notably veneering wide surfaces with thin sheets of wood into which floral patterns in marquetry could be inserted. The passion for colour found an even better outlet in lacquer decoration. The importation of works of art from the East had begun in Tudor times, but was of small account until after the Restoration. Then the taste be came widespread, Evelyn and other observers reporting their friends' houses to be furnished with Indian screens or panelled in the finest Japan—descriptions implying oriental lacquer. Such things came from China and were soon imitated in England, the art of covering furniture with successive coats of coloured varnish being known as "Japanning." New forms of decoration coincided with a multiplication of types. Day-beds, a form of couch with an adjustable end, and winged arm-chairs served for repose. A little later, sofas with back and arms carried comfort a stage further, patterned velvets mainly of Venetian origin and damasks woven at Spitalfields being the usual coverings. Bureaux with an enclosed desk were produced towards the end of the century, and chests of drawers came into general use. Mirrors were no longer rarities after the duke of Buckingham had established his famous glass-works at Vauxhall, the frames being carved, lac quered or inlaid. Charles, says Evelyn, "brought in a politer way of living which passed to luxury and intolerable expense." An example of this extravagance is afforded by the tables, mirrors and stands covered with embossed silver with which the king's mistresses furnished their apartments. Fashions succeeded each other with great rapidity. Chairs show these changes most clearly, developing in a brief period from mere seats into movable decora tion. They had floridly carved crestings and stretchers, while for the structural members many varieties of turning were employed. Scrolled legs were general under Charles II., being succeeded by taper and baluster forms a few years after his death. In beds of this period, the tester, back and posts are covered with material pasted on to the wood and matching the hangings. They were of enormous height with elaborately moulded cornices, and had ostrich plumes or vase-shaped finials at the corners of the tester. The ornate stands and side tables of this age demand special notice, for, profusely carved and often gilt, they are among its most striking productions.

The 18th Century.

At the beginning of the i8th century a new style arose. It was simple and dignified, based upon curved lines and entirely admirable in its insistence upon form. The cabriole-shaped support with claw-and-ball or paw feet was a salient feature, and early in the development stretchers were eliminated. This style depended largely upon finely figured wal nut veneers, and made but a sparing use of carved ornament. Chairs changed their character completely. They had hooped uprights and vase or fiddle-shaped splats curved to support the back, beauty and comfort being combined in the design. Tall boys, or double chests of drawers, cabinets fitted with shelves, and bureaux in two stages met the demand for greater convenience, while the types already known were much improved. About i 7 20 mahogany began to supersede walnut as the fashionable material, its consumption increasing with the repeal of the heavy import duties. The furniture which had prevailed during Anne's reign no longer satisfied the governing class, whose taste inclined to ostentatious magnificence. They demanded something grandiose and cumbrous, suited to the great Palladian houses for which it was destined. Inspired by the contents of French and Italian palaces, such furniture was largely the production of architects, William Kent, the most celebrated, having travelled in Italy before starting practice. The basis of design was classical, the manner baroque. Columns, architraves and entablatures are prominent with terminal figures and heavy scrolled supports, masks and acanthus scrolls being favourite ornaments. The carv ing was bold and often masterly, gilding, freely used, enhancing the effect. At Houghton, Holkham, Rousham and elsewhere, Kent's furniture may be seen in its proper environment, gilt mirrors and side tables with sets of chairs and settees covered with patterned velvets recalling the vanished splendours of that opulent age.About the middle of the century a fresh wave of French fashions produced an Anglicized version of the rococo style. It was romantic in conception, fantastic and capricious in the man ner of its working out. It banished the straight line and made asymmetry a cult, while it sought its ornament in conventionalized renderings of natural forms—shells, foliage and flowers. With it flourished the Gothic and Chinese "tastes," the one a travesty of a forgotten art, the other an attempt to exploit the furniture of an unknown land. Architects with a hold upon tradition were now challenged by cabinet-makers who produced their own designs. Chippendale, Ince and Mayhew, Johnson, Manwaring and many others published illustrated trade catalogues to adver tise their wares. Of these works Thomas Chippendale's Director is the most important. It affords an apt summary of contempo rary tendencies, and is at once eclectic and original. Chippendale borrowed his rococo from Meissonier, but depended much on his own fancy for what he deemed Gothic or Chinese. It was an age of specialization, and many varieties of furniture are represented, ranging from extravagant side-tables for saloons to ingeniously contrived little objects for bedrooms. In the explanatory notes mahogany is generally recommended, but many of the designs are to be japanned or finished in burnished gold. The contents of such houses as Nostell and Harewood (where the original bills are preserved) show Chippendale to have been a craftsman of genius; though he had many rivals scarcely less gifted. His name affords a convenient label for furniture of the middle of the 18th century—mostly the work of other hands. The classical reaction, which set in shortly after 176o, swept away tortuous forms and terminated licence in design. Robert Adam, whose name is inseparably associated with this movement, had, like earlier architects, studied in Italy. His fastidious taste rejected the art of the later Renaissance, and sought inspiration in the remains of antiquity. When he was given a free hand, furniture and decoration were included in his architectural schemes. What he could achieve when "the subject was great and the expense unlimited" Syon and Nostell remain to show. They are brilliant essays in the "antique style" with the contents carefully thought out in relation to their surroundings. This furniture makes a learned use of classical ornament, but paterae, husks, rams' heads and urns are less eloquent of the change than the symmetrical structural lines. At this time commodes and other objects intended for display were often of satinwood with marquetry or painted decoration, the latter copied from designs by leading artists. The style as Adam conceived it was too severe and scholarly to be widely appreciated. It was modified by contemporary cabinet makers, and may be seen translated into popular terms in Hep plewhite's Guide (1788). In the process the furniture has lost its ceremonial character, and become simple, homely and graceful. It retains, for the most part, symmetry of form and excellence of proportion. Heart and shield-shaped backs on chairs and settees with tapered and fluted supports are noticeable features, while feathers, wheat ears and shells are prominent in the painted or inlaid decoration. The movement was towards lightness and elegance, and furniture of a distinctly feminine kind is found represented in Sheraton's Drawing Book (1791). This period saw the highest technical accomplishments, and a degree of specializa tion hitherto unapproached. Sheraton's designs for fitted washing stands, dressing- and work-tables are triumphs of ingenuity and eminently practical.

At the end of the century a strange archaeological revival, based upon a closer study of Greek, Roman and Egyptian remains produced the Empire style and that modified version of it which became current in England. The chief English exponent was Thomas Hope, an amateur designer with some antiquarian knowledge ; but when the fashion was taken up by cabinet makers the results were often woefully incongruous. They essayed the production of Roman bookcases and sideboards undeterred by the lack of classical precedents, and to what depths of incongruity they descended may be seen in Sheraton's later publications and in George Smith's Household Furniture. Rosewood was used with bronzed or gilt ornament and metal inlay, sphinxes and animal terminals being favoured as supports. With the last phase of this style, prolonged into the reign of George IV. and growing ever more grotesque, the making of furniture ceased to be an art. The introduction of machinery ended the craftsman's direct respon sibility and robbed him of pride in his work. The old tradition of sound craftsmanship lingered, and may be detected even in the cumbrous productions of the Victorian age, devoid though they be of any aesthetic interest. It may confidently be said that the domestic arts were never at lower ebb than during this period.

The Pre-Raphaelites and Modern Movements.

Early in the '6os the complacent acceptance of mass embellished with un gainly ornament was challenged by the movement inaugurated by William Morris and a group of pre-Raphaelite artists. They sought to rehabilitate craftsmanship, and with this end in view their sympathies were naturally drawn to the middle ages when craftsmanship was in its prime. Their work is distinguished from the earlier Gothic revival by greater understanding and a regard for modern needs. That it can wholly escape the charge of being "sham mediaeval" cannot be maintained, but it was sincere in intention and provocative of thought. Morris realized part of his ambition, for he trained a company of enthusiastic and highly skilled craftsmen. The propaganda spread in spite of the prevail ing Philistinism, and a marked improvement in taste was the result. For an appreciative few Morris furniture continued to be made, and, among the inheritors of his traditions, Ernest Gimson deserves honourable mention. The movement was, however, too typical of a time when the arts had become disastrously divorced from life. It found its chief supporters among a cultured minority with exclusive standards and a somewhat superior attitude; in consequence there was more than a hint of the "precious" and artificial about the furniture made for them. A notable result of pre-Raphaelite activities was to direct attention to the striking merits of furniture which had been banished by the Victorians. It was rescued from obscurity and the collecting habit spread, rapidly producing a huge crop of "fakes" and reproductions. This habit has undoubtedly determined the character of English furni ture for nearly 5o years. It has stifled originality and degenerated too often into an unintelligent craze, while it must be held re sponsible for the cheap and horrible travesties of historic styles, which under the label "period" have done so much to degrade public taste. In the last decade there have been unmistakable signs of a renaissance, and something of the Continental enthu siasm for modern furniture has spread to England. In the pro ductions of this new school fitness for purpose is again con sidered and great attention is bestowed on the material, many beautiful, exotic woods being used with striking effect. Ornament is unobtrusive (excepting in the more fantastic examples), and even mouldings are kept in subordination. The forms are often eccentric, reflecting the latest aberrations of fashion ; attempts to produce jazz or cubist furniture are not unknown. At the present day the opportunities are quite severely limited by the inevitably high cost and also by lack of patronage. The outlook is promising, both on account of the genuine originality sometimes displayed by designers with a firm hold upon tradition, and because fine crafts manship is again highly prized for its own sake. The Twentieth century will possess a distinctive style of its own when a few really gifted designers emerge to consolidate the gains which have already been won.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-D. Marot,

Oeuvres (1712) ; J. B. Du Halde, DeBibliography.-D. Marot, Oeuvres (1712) ; J. B. Du Halde, De- scription . . . de l'Empire de la Chine (1735, Eng. trans. 1741) ; B. Langley, Treasury of Designs (1740-5o) ; W. and J. Halfpenny, New Designs for Chinese Temples (1752) ; T. Chippendale, The Gentle man and Cabinet-Maker Director (1754; ; W. Chambers, Designs of Chinese Buildings ; T. Johnson, One Hundred and Fifty New Designs ; Ince and Mayhew, The Universal System of Household Furniture (1762-63) ; M. Lock and H. Copeland, A New Book of Ornaments (1768) and A New Book of Pier Frames, etc. (1769) ; R. and T. Adam, The Works in Architecture 0773) ; Heppel white, Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer's Guide (1788) ; T. Sheraton, The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer's Drawing Book (1791) ; G. Smith, Designs for Household Furniture (18o8) ; H. Havard, Diction naire de l'Ameublement (I887-9o) ; P. Macquoid, A History of English Furniture (19o4) ; C. Simon, English Furniture Designers of the Eighteenth Century (1905) ; F. Lenygon, Furniture in England (1914, rev. ed., 1924) ; A. T. Bolton, The Architecture of Robert and James Adam (192 2) ; P. Macquoid and R. Edwards, The Dictionary of English Furniture (1924-27). (R. ED.) The heritage of the American colonists on their first arrival in the New World was the household art of the countries from which they came: English in Virginia and New England, Dutch and Swedish at first on the Hudson and the Delaware and German as well as British in Pennsylvania. Even among the leaders few rep resented courtly fashion. Hence, the earliest household decoration and furnishing, after the period of primitive makeshifts, reflected rather the character of the common houses of the small towns and rural districts abroad. In these the fundamental element deep into the 17th century, in Germany even into the 18th, was a survival of the art of the middle ages, with its structural emphasis, its simple forms derived from materials, tools and use.

Thus in New England in the 17th century we find the clay filled walls, the timber houses roughly plastered and whitewashed, or perhaps wainscoted with wide moulded boards, which, standing vertically, served as the partitions. The joists of the ceiling were exposed, supported on heavy moulded summer-beams; the great fireplace was likewise spanned with a huge beam, and was devoid at first of any moulded frame. The effect was one of homely solidity, achieved by the frank revelation and elaboration of every element of the construction.

Into such houses in New England and Virginia went furniture of Jacobean oak, a few pieces doubtless brought over by the leaders, but the vast majority made in America after remembered models, from the abundant supply of native woods, chiefly American oak and pine. They included chests, court and press cupboards, trestled tables and forms and, at first, but a few chairs of the turned or wainscot types. One variety of armchair with turned spindles has acquired in America the name of Carver chair from the familiar example belonging to John Carver, still preserved at Plymouth. Other characteristically American types are two forms of chests found in the Connecticut valley : the "Connecticut chest" of the lower valley, with Jacobean spindles and the panels carved with a tulip decoration; the "Hadley chest" further up the valley, of which the frame likewise has incised carving. In the English colonies the furniture, as well as the woodwork, was generally left without paint or other finish. Inventories of the better 17th-century houses reveal that they contained much in the way of hangings, including tapestries and needlework, as well as treasures of plate made by the American silversmiths of the time, and pewter by local pewterers.

Similar in their generally mediaeval character were the interiors of the Pennsylvania-German houses, where, however, there was a rich colour, in the painted decoration of the chests with motives of birds, tulips and other traditional elements, the illuminated texts, birth and marriage certificates which hung upon the walls. It was the German colonists also who first made any high de velopment of pottery, as in the Pennsylvania slip ware, with similar decorations, and in glass-making, as in the wares of Stiegel and Wistar. The familiar hand-woven coverlets, chiefly of blue and white, were likewise derived from patterns brought in by the German weavers.

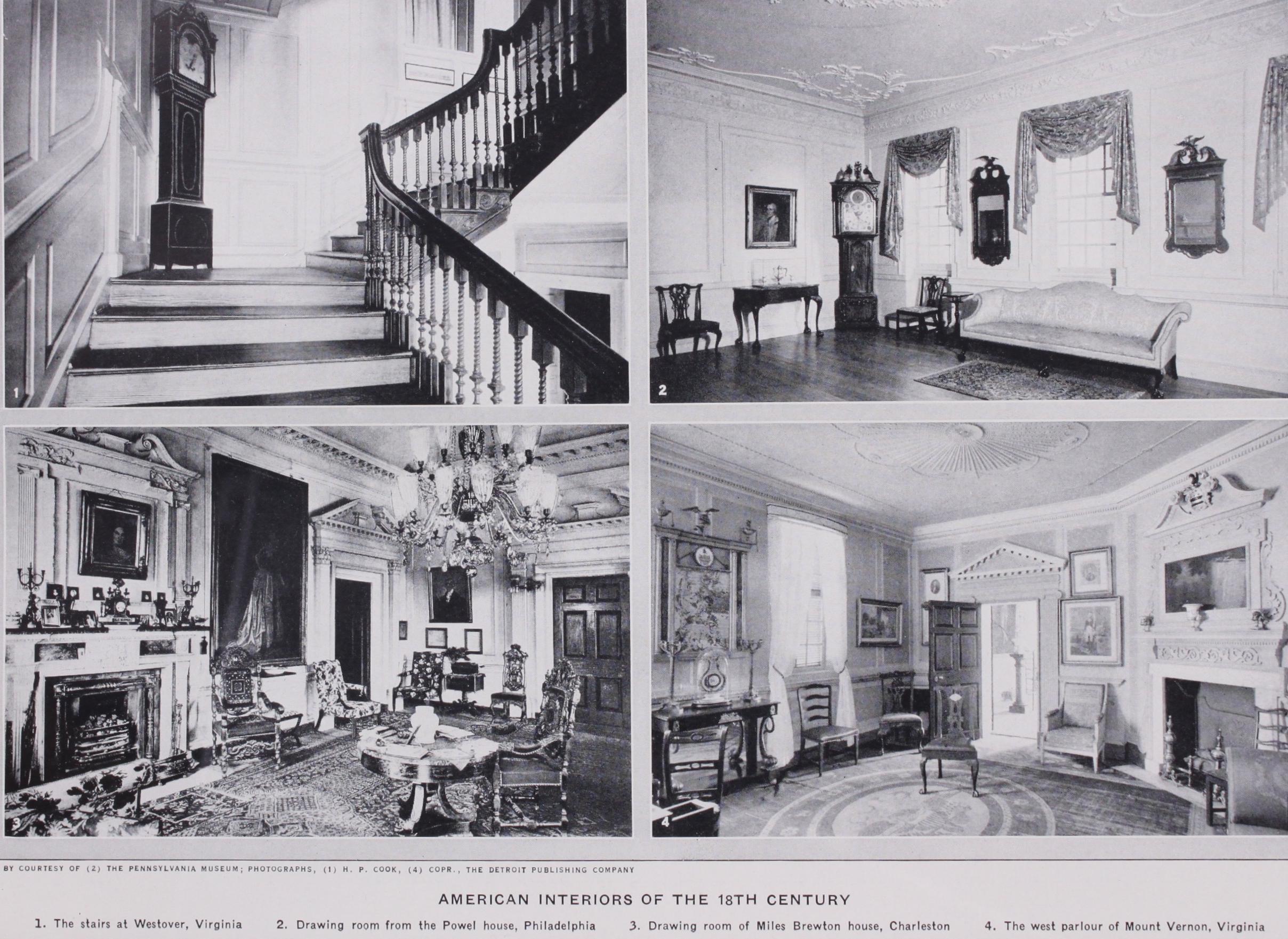

Following the evolution of style in England, under the Com monwealth and the Restoration, there appeared in America chairs of the Cromwellian and Carolean types, with spiral turnings and baroque scrolls, with seats and backs upholstered in needlework or with panels of cane. The chest with a drawer or drawers then made its appearance. The founding of Philadelphia by William Penn in 1682 brought to America for the first time the decoration of the period of Wren, which had appeared in London after the great fire and had been developed by Wren and Daniel Marot in the reign of William and Mary. Its influence only became wide in the colonies with the opening of the i8th century. The con struction disappeared beneath a formal interior finish. Panelling took the place of sheathing, the fireplace was surrounded by classic mouldings, at first boldly projecting, to produce the chimney-piece. The doors and windows, too, were surrounded by classic frames, and the wall might even be divided, in the finest houses, by pilasters. In the staircase the open string, with carved brackets at the end of the steps, was adopted; the balusters and newels, more slender, were richly turned, often in varied spirals.

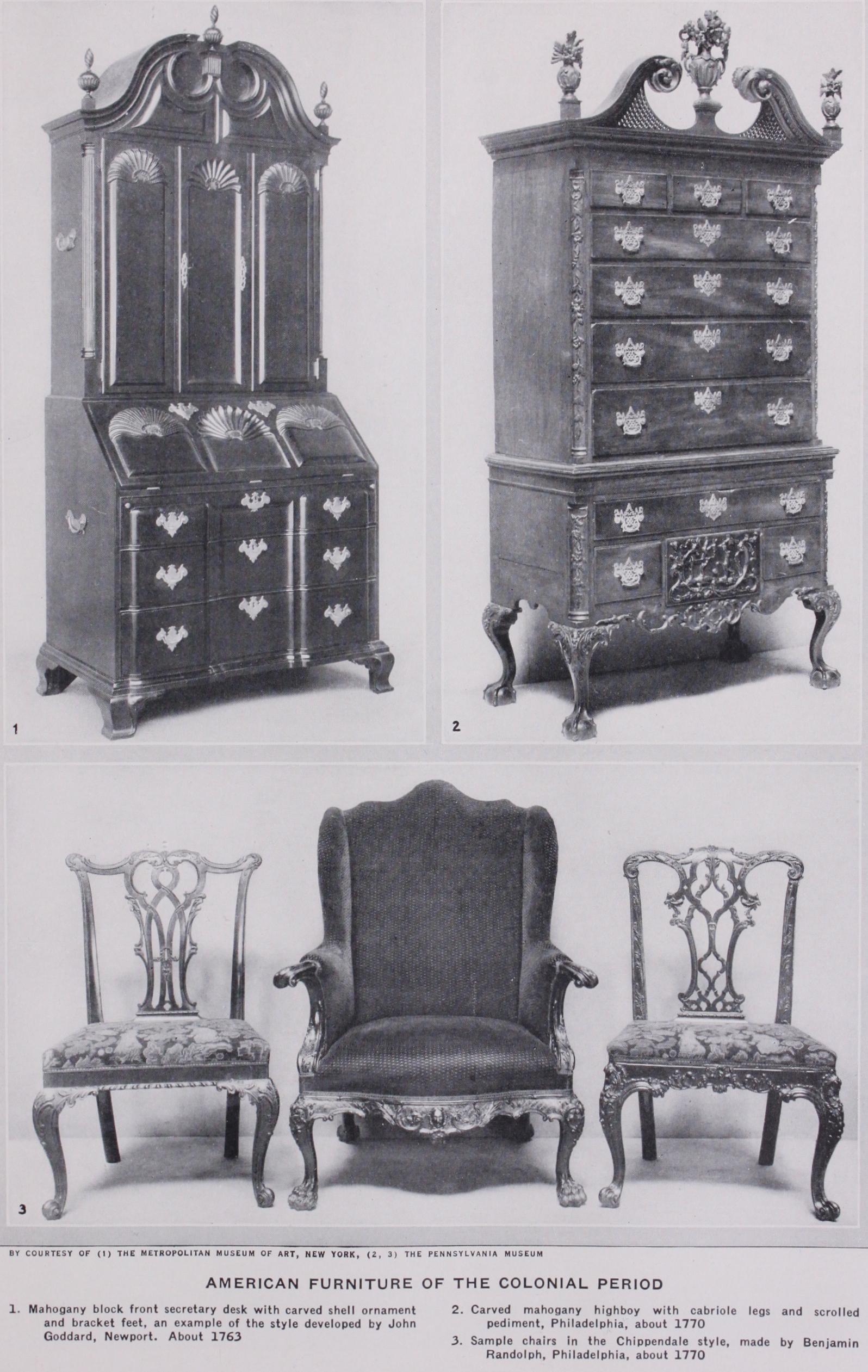

Walnut became the favourite wood in furniture, until super seded by mahogany in the middle of the century. The style of William and Mary, with its trumpet turnings in legs of chairs, dressing tables and chests of drawers (now elevated on frames to constitute "highboys"), its high curved chair-backs; and that of Queen Anne, with its cabriole legs, succeeded one another some score of years after the advent of these monarchs in England. To this time we may refer the first creation of the American types of Windsor chairs, many of them so different from the English Windsors and owing more to the roundabout chairs. In hickory the Americans found an admirable wood for the bows and spindles. The early Georgian style was adopted in America simultaneously with the use of mahogany, so that mahogany pieces are to be found in the colonies of types which in England were disused before the advent of this wood. Certain types were also created in America, most notably the "block front" secretaries and dress ing tables made by John Goddard of Newport about 1763, with alternate projections and recesses crowned by carved shells.

The heyday of the colonial style came in the fifteen years before the Revolution and coincided broadly with the Chippendale influ ence. Chiefly with the publications of Abraham Swan the forms of the French rocaille, with its characteristic pierced shell work, reached America and were used in the adornment of the great mansions of Annapolis and Philadelphia, and such fine houses as that of Jeremiah Lee in Marblehead and Miles Brewton in Charles ton, or the Philipse Manor in Yonkers. The delicate carving of the overmantels, with their scroll tops, was matched in the airy relief work of the plaster ceilings. This was the period of the great Philadelphia cabinet and chair makers, such as William Savery, whose earlier work is of a simpler character, Benjamin Randolph, James Gillingham and Jonathan Gostelowe, whose workmanship compares with that of the London craftsmen. The most characteristic pieces, distinctively American, are the high boys and lowboys of mahogany, their tops and skirtings carved with delicate shell ornament. The trade of the upholsterer now also flourished; the craft of the silversmith in the hands of such men as Philip Syng and Revere the elder excelled in adaptations of fine Georgian models.

On the eve of the Revolutionary War the influence of the Adam style began to be seen, as in the garlanded ceilings at Kenmore and those executed for Washington after the outbreak of hos tilities. The war postponed any widespread effect until after the resumption of relations in 1783. In the following year John Penn, of London, in building his little box, Solitude, on the banks of the Schuylkill, gave the first complete example, and others were furnished in the great Philadelphia mansion of the Binghams and the country seat of William Hamilton, the Woodlands, near by. The style was introduced in New England by Charles Bul finch who found an apt follower in the Salem carver, Samuel McIntire. Mantels and doorways were adorned with delicate composition ornaments, at first imported from London, later made also by American craftsmen like Robert Wellford of Phil adelphia. Ingenious adaptations of the Adam motives, made with gouge and auger, were widely employed about I Soo. Owing to war but little characteristic Adam furniture was made in America, but the developments of Heppelwhite and Sheraton were early and eagerly adopted. The later Georgian models also gave in spiration to silversmiths like the patriot Paul Revere, in Boston, and Joseph Richardson in Philadelphia. Through the new relations with France not a little fine French furniture of the Louis XVI. style was imported to America, as, for instance, by Washington and by such residents in Paris as Jefferson, when American min ister, and James Swan of Boston. Both Sheraton and Directoire models were adapted by the gifted cabinet-maker in New York, Duncan Phyfe, whose lyre tables and sofas are among the most refined of American furniture designs. Of this general character must have been the original furnishings of the White House under Jefferson, destroyed by the British in 1814. In the refurnishing of the White House under Monroe, about 1817, it was furniture of the French empire and Restoration which was imported. The heavy mahogany of this classic style with its gilt mountings filled the high, chaste interiors of the American houses of the Greek revival and persisted until the advent of Victorianism.

See TEXTILES ; RUGS AND CARPETS ; METAL WORK ; LAMP ; LIGHTING AND ARTIFICIAL ILLUMINATION ; TAPESTRY. (F. KI, ) BIBLIOGRAPHY.-For the interior architecture of houses see R. T.Bibliography.-For the interior architecture of houses see R. T.

Halsey and E. Tower, The Homes of our Ancestors (New York, 1925) . W. R. Ware. The Georgian Period (Boston, 3 vols., 1898-1902, 5th ed., New York, 1923) ; D. Millar, Measured Drawings of Some Colonial and Georgian Houses (New York, 2 vols., 1916 ff.) ; F. Kimball, Domestic Architecture of the American Colonies (New York, 1922) ; L. French, Colonial Interiors (New York, 1923). For furniture and crafts see I. W. Lyon, Colonial Furniture in New England (Boston, 1891, 2d ed., 1924) ; L. V. Lockwood, Colonial Furniture in America (New York, 2 vols., 1902, 3d ed., 1927) ; E. Singleton, The Furniture of our Forefathers (New York, 2 vols., 1901) ; F. C. Morse, Furniture of the Olden Time (New York, 1902, 2d ed., 1917) ; W. Nutting, Furniture of the Pilgrim Century, (Boston, 1921) ; C. O. Cornelius, Furniture Masterpieces of Duncan Phyfe (New York, 1922), and Early American Furniture (New York, 1926).

The Chinese mode of living is quite different from that of the Japanese, though in art and culture the two peoples have many points in common. The difference in the diet and the difference in the style of their dress, manifest themselves in their houses and in their mode of living. Unlike the Japanese, the Chinese house interior is profusely decorated and furnished with chairs, tables, beds, stands, cabinets, screens, etc.

In an ordinary Chinese house the guest room, which opens to the courtyard, has a bare tiled floor, and is furnished with tables and usually 8 chairs. The place of honour in the room is marked by the long table, kew tai (bridge table) placed at the middle against the back wall where hangs a painting or a pair of hanging scrolls bearing quotations from the Classics or both. Upon the long table are placed vases of flowers and objects of art. Directly in front of it one invariably finds a square table named, for good luck, Pa Hsien Tai (table for the eight Taoist immortals). On either side of it is placed a square stool or an arm chair for the honoured guests. The back wall is often formed of a screen partition, bing mun, behind which there generally is another room with a sacred shelf, sun low, where deities and the spirit of the ancestors are enshrined high up near the ceiling; and below on the floor a place is provided for the god of the earth, to chu sun. In homes of the common people, the sacred shelf constitutes the main feature of decoration in the house, usually occupying the most prominent place above the bridge table in the guest room. In the houses of the upper class, there is more than one guest room or parlour. There is an entrance room, through which the guests pass into the courtyard and into the cha tai, a small room where the visitors may change their street attire into a proper dress before appearing in one of the guest halls, ka dong.

By removing the Chang thou (the long windows), the latticed panels between the pillars, the guest hall is thrown open to the courtyard for the entire length. Some homes are provided with another guest hall, kwa tai (flower parlour), which may be used for the banquet as well. Whenever possible, the screen partitions (not sliding screens like the Japanese ones) are employed so that two or more rooms may be used as one big room when a large party is entertained. The main wall, as well as the side ones, are generally covered with many paintings or scrolls mounted as the Japanese kakemono, which are changed periodically so as to keep them in harmony with the season. In some houses tapestries take their places. The parlour generally has a tiled floor and the bed room a wooden floor, rugs or carpets being very seldom in evi dence even in the wealthy homes, though the country has long been famous for the production of splendid rugs.

The cabinet, tall and dignified, with shelves and chest of drawers inside the swinging doors, occupies an important position in the living rooms of the Chinese house. No less significant is the bedstead, which is often a work of art in its design and embellishment with carvings and paintings. The bedstead usually combines a small compartment to contain a chair and a table. Sometimes the bed is enclosed in a large portable structure with a ceiling, the wooden parts being decorated with beautiful carv ings, generally lacquered over. The curtains for the bed, during winter, are of double satin, and in summer either of white taffeta or of very fine gauze, both of which are open enough to permit the air to pass through and close enough to keep out mosquitoes and other insects. The structure is a room in itself, being pro vided with a door and generally so large that it is fitted with shelves and contains, not only the bed of ample size, but a table, chairs and a cupboard. The usual furniture is in the dark, heavy, precious hardwood, tzu-tan. The chairs with seats of the same material, and backs with an inset of tai-lee-sek, marble from Yunnang province which has natural pictorial marking like the paintings after the "southern school," have their simple dignity. Little square stands used for serving tea are often topped with wan-sek, the ordinary marble.

Both tables and chairs are often inlaid with mother-of-pearl in floral and bird designs, but the best wood is preferred to be admired in its natural state. Some pieces are lacquered in various colours, while others are lacquered and carved or incised, many of them presenting impelling dignity by their shape, size and tasteful decoration; some of the best examples may be seen at the Victoria and Albert museum. With the massive furniture, heavy carved beams on the wooden ceiling, and panels of latticework that shut off the glare of the courtyard, the room is restful. Superb workmanship in decorative art, with inlay of ivory, col oured horns, mother-of-pearl, etc., on a lacquered ground is shown on the tall folding screens used as partitions in the room. A single panelled screen, ping-mun, also called a devil screen, is placed at the entrance to the house to act as a buffer. While it prevents a view of the interior from outside, it serves to deflect, or ward off, according to the Chinese superstition, the evil spirit.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-Herbert

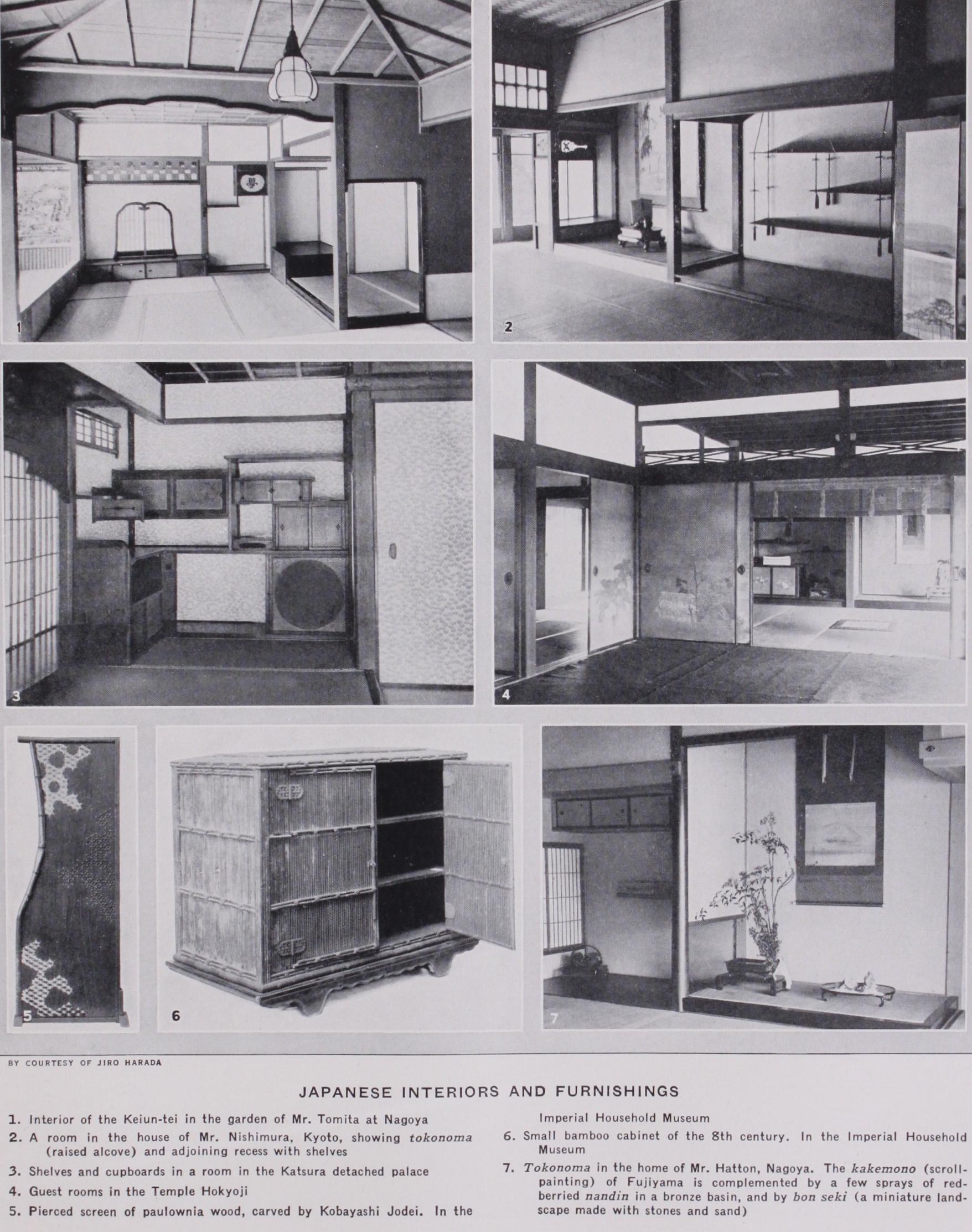

Cescinsky, Chinese Furniture; S. W. Bushell, Bibliography.-Herbert Cescinsky, Chinese Furniture; S. W. Bushell, C. M. G., Chinese Art; Dr. C. Ito, The Decoration of the Palace Build ings in Peking.The refinement of simplicity, which finds its aesthetic ideal in the natural beauty of materials and is compatible with the aus terity of architectural form, is a keynote of a Japanese house interior.

The Walls.

Rooms of various sizes are made by the use of walls and f usuma (sliding partitions of wood covered with pat terned or painted paper or silk), running in grooves, which usually measure some 6 ft. in height and 2+ to 4 2 ft. in width. Shoji, the equivalent of windows, consist of light lattice-work to which is pasted white translucent paper, and also slide in grooves. The grooves run between squared wooden posts, and allow the screens to pass one another, rendering hinged doors unnecessary, and permit of the screens being lifted out altogether, thus throw ing a series of rooms into one great apartment. The "filling" (varying in height from 2 to 41 ft.) between the beam over the screens and the ceiling, is generally, in good class houses, of lat ticed wood or bamboo or of pierced woodwork called ramma. The carving of the ramma, often elaborate in palaces and mansions, should be in harmony with the character of the room. Those in certain palaces and temples in Kyoto are exquisitely carved, some having intricate designs in pierced work carved from a single piece of wood, showing flowers and birds on one side and trees and animals on the other, and, in one instance, a flight of wild geese over swaying pampas grass so carved that a painting of the silver moon on the upper wall of the next room may be seen through the openings in the carved ramma, beyond the dark silhouette of the carved flying birds.

The Floors.

The floor boards are completely overlaid by tatami, straw mats some 2 in. thick and measuring about 3 by 6 ft., each one covered by finely woven grass matting. The size of the room is computed in mats, according to whether it needs 41, 6, 8, Io, 12 or I 2 z mats to cover the floor. In ordinary dwelling houses a room is seldom larger than 15 mats. The spot less matting of closely-woven fresh reeds, bound on the long sides of each mat with a narrow strip of dark linen, together with their pale green colour neutralized by light filtering through the paper screens, and their fresh fragrance, appeal strongly to natives of Japan, and those who can afford it continue to preserve this fresh ness by reversing and changing the top matting from time to time.

The Ceiling.

The ceiling is equally simple. In an ordinary dwelling house it is about 9 ft. from the floor and formed of thin, slightly overlapping panels of unpainted wood about 12 to 18 in.

wide, whose monotony is broken by parallel strips some 18 in. apart running across the ceiling, and invisibly nailed from above. Since the grain of the wood forms part of the decorative scheme in the interior, the boards are cut from a single tree to insure uniformity. The panels, 6 ft. in length, must be so laid as to suggest continuity of the grain across the room, and must be carefully planed by the carpenter, for they are to be admired in their natural state and no flaw in human handicraft must be allowed to spoil their intrinsic beauty. All the woodwork of the interior must in the same way be left virgin, unspoiled by colour stain or paint, with occasional exception of the narrow framework of the fusuma, and the tokobuchi—a piece of wood several inches in width and thickness running along in front of the tokonoma (see below) to its full extent—both of which may be lacquered in harmony with tatami borders or the tokonoma post. This is often made from a tree having some special tint or texture, or else made to conform to its natural curve of growth. A portion of its bark or the worm-eaten marks beneath it, or the stump of a branch or some other witness of nature, is preserved, thus focus sing on the tokonoma—the most important feature of a Japanese interior—the significance of the design of the room.

The Tokonoma.

This slightly raised recess or alcove, usually built into the wall at right angles to the verandah, is commonly from 2 to 3 ft. deep and 42, 6 or 9 ft. wide proportionately to the size of the room. In it are displayed the only independent decorations in the room. A painting or a set of two or three kakemono (hanging-paintings mounted on rollers) occupy the back wall of the alcove, and a vase holding the ike-bana or flower ar rangement (q.v.), an incense burner or a wood-carving, or some other art object, is placed on its floor. They must each be in harmony with the season or with any special occasion which may befall, and are chosen with a view to give pleasure to an expected guest. There may be many kakemono put away, especially in old families, but only one is shown in the tokonoma, selected to do honour to the guest. If he is likely to enter other rooms having a tokonoma, a distinctive atmosphere must be created in each, while emphasizing some central harmonizing idea. The flower arrangement and other decorative art objects must be complemen tary to the painting. Thus a kakemono of the moon may be accompanied by a few sprays of autumn flowers, artistically arranged in a bamboo basket, and a small bronze censor in the shape of a cottage, thus suggesting a fishing hamlet on a tranquil evening of autumn. Or a painting of a waterfall may hang in the tokonoma, while on its floor is placed a rectangular bronze vessel well filled with water and with a few water-lilies appro priately arranged in it. In a small room the same atmosphere may be achieved by showing a narrow kakemono of a waterfall in a roughly-executed black monochromatic style and placing on the floor a single white blossom of Hibiscus mutabilis, half-con cealed among its freshly moistened leaves, displayed in a slender bronze vase with very cold water so that the moisture collects outside and trails down over the beautiful patina, creating the suggestion of a miniature pool on the round flat lacquered board of liquid black upon which the vase stands.Thus the guest is brought to feel the very spray from the waterfall, transforming the confined room into a fitting place in which to entertain visitors on the hottest of summer days. An alternative to the painting is a couple of lines of poetry on which the guest may meditate on his entrance into the room. His atten tion may next be led to a bon-seki (q.v.), a tiny landscape con trived with natural stones and sand, on a black lacquered tray at the foot of the kakemono. It may call to mind some familiar scene—a rocky promontory with an island near by, and beyond the moonlit sea the dim contours of undulating hills. The poem on the kakemono (for calligraphy is also treated as a pictorial art) thus quickens with new meaning for him and he can share the poet's inspiration.

Other Decorations.

In a companion recess adjoining the tokonoma are chigai-dana—shelves arranged stepwise—for addi tional art objects and there is usually a small cupboard with appropriately decorated sliding doors either above or below the shelves. There may also be a low writing-place built at the side from which the light comes, in front of the tokonoma, where lacquered boxes for paper and other writing paraphernalia can be placed, further decorating the room. What articles, and how and where they are to be arranged in these places to conform to the general scheme and to afford the maximum of decorative value and aesthetic pleasure, has been an aesthetic study for centuries. In the time of the Shogun Yoshimasa (1444-73) a set of sys tematic rules of decoration had already been formulated, and is still followed by some of the "tea-men." There may also be placed by the low writing-table in the master's room, a portable lacquered set of shelves or a cabinet carrying a few objects of art for his delectation in moments of leisure.Thus simplicity of display is fully compatible with wealth of possessions. The same object is rarely seen twice in a dozen visits. Hundreds of beautiful things may be stored in the treas ure-house. Guided by his knowledge of the character and tempera ment of his guest, his recollection of the impression made by the things on view on former occasions, a Japanese host will select from his store, always aiming at giving pleasure and a delightful surprise to his guest.

Sometimes a skirting of strong white or grey paper about a foot high as a protection against the broom is seen on a Japanese wall, but it is never papered or covered up by paintings, although a gaku, consisting of a painting or a few written characters expressing or suggesting a poetical sentiment or a truth may be framed above the fusuma. Plastered earth and. sand, variously coloured, and mixed with boiled funori (Gliopeltis Arcata) to give solidity, is used for the interior surfaces of the lath and plaster walls, and the pounded shell of little fresh-water bivalves or iron filings is sometimes mixed with the sand for their decorative value. Plaster in tint of smoke, mist or cloud, often has a hard and resistant surface.

Furniture.

In the Japanese house the furniture is conspicu ous by its absence. There is neither table nor chairs such as are used in China or in the West. Everybody removes his or her shoes, sandals or clogs upon entering the house, and even slippers or house sandals are left outside in the wooden corridor. People sit, or rather kneel and sit back on their heels, on the tatami on flat square cushions. Each person is provided with a tabako-bon (smoking set) in summer and a hibachi (charcoal brazier) in winter. In some houses to-day gas or electric stoves are fitted, but the brazier is the characteristic means of warming a Japanese interior. It may be of bronze, porcelain or wood decorated with lacquer, and is furnished with a pair of small tastefully designed and ornamented fire-irons like chopsticks. Braziers are usually small and portable.Beds may be arranged on the floor in any room at night by piling up wadded quilts, which are folded and packed away in the closet, after airing in the sun, in the morning, leaving the room clear for other uses during the day. A tansu, a chest-of drawers in plain paulownia wood, may betray the sleeping apart ment, but this, too, is often placed in the closet, shut off by fusuma, so as not to be seen. A clothes-horse is as a rule also placed out of sight behind a screen. Byobu, ornamental folding screens of 2, 4 or 6 panels decorated with writing or painting, or carried out in plain gold, serve many a convenient purpose, warding off draughts or hiding an undesired view. A single-panelled screen called tsuitate is usually placed in the entrance-room, to allow of the front shoji being pushed open without exhibiting the interior of the house to a caller. Even the dining-room is without any sign of its use, a collapsible low table being brought in for family use at mealtime, or food being carried in and served to each individual on small low lacquer tables called o-zen, kept in the kitchen cupboard when not in use.

In the summer heat the ordinary fusuma and shoji are fre quently removed and replaced by others specially made of rushes or split bamboo to permit the passage of any breath of wind that may happen to stray into the house. The floor, too, may be covered over with rattan matting, to impart coolness; and misu or blinds made of split bamboo or rushes, may be suspended from the eaves to give shade and privacy.

Simplicity the Keynote.

Japanese rooms are thus extremely simple, though neither barren nor cheerless, since every detail of form and colour is studied and harmoniously combined, even the joinery being so perfect that not a trace of a nail can be seen anywhere, with the result that, at least for beauty, the empty room is sufficient in itself. There is a sense of relief in this absence of furniture. 'these neat and airy rooms, so restful and so spacious, may be opened at will for their entire width onto a tiny landscape over which the eyes delight to wander. Or they may be closed up completely, leaving the occupant alone with an iron kettle (an object of art in itself) gently boiling on the charcoal fire, over looked from no window, but companioned by the silhouettes of bamboo or pine branch in the garden forming countless attractive patterns on the creamy paper of the shoji. In such a room may be admired an ancient tree of stately form, growing in a pot placed in the tokonoma, and still retaining its dignity in its miniature form. Freed from the distraction of furniture, the men and women in the room recapture their dignity and significance. In the sim ple form in which the exigencies of construction determine the refined and reserved quality of the decoration, and the furnishings are reduced to the essentials, while the subtly blended colouring and the constant variety of the view on which it can be made to open build up a composition of delicate lines and graceful forms, the Japanese interior well fulfils its main and consciously recog nized functions : it supplies an appropriate setting for clean and simple living. (See JAPANESE ARCHITECTURE; JAPANESE SCULP TURE; WOOD CARVING: Far Eastern; BON-SEKI; BON-SAI.) BIBLIOGRAPHY.-E. S. Morse, Japanese Homes and Their SurroundBibliography.-E. S. Morse, Japanese Homes and Their Surround- ings; R. A. Cram, Impressions of Japanese Architecture and the Arts. (J. HAR.) Any consideration of the principles of interior decoration as de termined by modern needs should contain a comparison between the work of past periods and that of our own. Sound development does not lie in a mere production of novelties ; the whole circum stances of the age must lead in a natural line to the new form. We know that the mentality of our ancestors up to the beginning of the 19th century was unblushingly feudal and that comfort itself was sacrificed to the ideal of magnificence. Anybody with any pretensions had to be magnificently dressed, and his personal status was indicated by a suitable uniform, with abundance of gold, long tassels and richly-chased arms. Obviously the rooms in which these men lived had to be equally magnificent. Tradition, assured culture and discipline, combined with great naivety, made this possible. We can still imagine to-day that the craftsman found salvation only in producing work of the best possible quality; but unfortunately we have no conception left of how it was possible to make him so happy that he produced one new form after an other, with amazing power, and how he was able, without any serious friction, to carry all his contemporaries with him and, lacking all the enormous modern facilities, yet to spread his ideas throughout the whole civilized world. The age which followed gave the bourgeois its chance, and simplified everything ; the form aimed at was more severe, but despite this limitation there was an increase of refinement, and a great and sometimes fantastic, but suggestive multiplicity of design appeared. This phase ended in Europe about the middle of the 19th century, and was suc ceeded by a dreary, generally mistaken imitation of earlier styles, intolerant of all else, and fatal to all genuine tradition; corrupting work and making it superficial, and leading at the best to falsifica tion. Although the modern man is changing completely in ex ternals, concentrating increasingly on practical matters, and would certainly not dream of appearing in the street dressed up as a knight, in the decoration of his home he thinks it necessary to copy some form of decoration belonging to the past : In this way he loses all feeling for real development and, through his art studies which are generally superficial, loses all touch with living art. Work is mostly performed by machinery. The engineer is preoccupied with his constructive, calculating methods ; nothing is sacred to him; he can make anything to order; and the products inflicted on us, the cast-iron stoves, benches and furniture, the first motor-cars, the pots and pans and small artistic products with a superfluity of decoration in every style, the Gothic not excepted, have accustomed the great, ever uncritical majority to buy the most hideous objects with indifference, and to lose all sense of natural beauty and of individual form. This process has been carried so far that business men have made serious good work impossible through their so-called "cheap goods." People with taste draw back from all this and collect antiques and generally end by forgetting that it is their duty as it was formerly the duty of the court, the nobles, the Church, and later, of the educated classes, to foster a high standard of art and craftsmanship. The modern movement has begun by realizing this and by searching for a way out. Ruskin and Morris both sought to awaken hu manity to the beauty of good craftsmanship and genuine material, and gradually introduced old techniques and methods of work. As a result of their teaching wonderful works in metal, leather, ceramics and textiles were produced, but were often created in by gone styles, although freely adapted. Ashbie, in 1885, went farther, and produced in the Guild of Handcraft excellent modern silver work—although again in antique form; the development of the art of the Scot Mackintosh into a wholly new, original style is amaz ing. His rooms in pale grey wood and violet strutts and em broidery adorned with rose-red flowers, his original lighting and glass, his heating apparatus, indeed every detail, were remarkable and full of promise. Innumerable forces bestirred themselves, seeking to evoke, in England first, then in Holland, Germany, Austria, France and the Scandinavian countries, a great, genuine and creative artistic movement, to help the world to reach again a unity of culture. At first there was no radical transformation. The business interests were alarmed, disconcerted, and, without established precedents to guide them, were quite bewildered. The public also was wholly bewildered, in part enthusiastic, in part misunderstanding and prone to severe criticism.Yet the movement, which ended with the beginning of the war in 1914, succeeded in making itself felt everywhere. To-day we are confronted by a movement which is even stronger and ob viously more radical than before, which has learnt in the hard school of war and poverty which followed it many a lesson which the great public needed and was bound to receive.

In modern interior decoration, now that it is recognized that dec oration alone, even new forms of decoration, admittedly does not create style, the great need is to have a complete apprehension of the task in all its essentials. We no longer think in terms of pil lars, window-frames and decorations of one type or another; we create the room to be the environment of some particular human occupation, adapted for that purpose, simple and concise in form, and constructed in the best and most suitable materials. Manifold needs give birth to equally manifold expressions and we are be ginning to construct with comparative certainty, without the risk of committing blunders. A city of to-day looks quite different from the city of a hundred years ago. With the help of new tech nical contrivances we can achieve quite unprecedented effects, be cause our first care is to apply all the methods of sanitation, to preserve correct proportions in design and to consider the needs of every class of society. In a modern house bacilli lead a sorry existence; light and air flow through every corner and cranny. Glass, manufactured in every possible way, set in metal, to econo mize space on the frames, is replacing white walls. We attach the chief importance not to the lighting apparatus but to the light, and similarly we care more for the heat than for the heating apparatus.

First consider the living rooms. The size and height must partly depend on circumstances ; the height must not be less than 7 ft. 6 in. to 8 ft. 6 in. One wall—facing east, south or west should be glass from ceiling to floor; many rooms, such as the breakfast room, winter garden, living rooms and day nurseries may have two or even three sides of glass. Double glass, reaching to the floor and lined with water-tight material, may provide a space for flowers, plants and perhaps statuary. Besides having a door in the inner glass wall there could be a second door in the outer glass leading on to a balcony or a terrace. There should be no pernickity curtains, blinds, etc., but some suitable means of protection against excessive sun. In first class work the actual wall surfaces are sometimes left without further treatment with fine effect. In rooms already built and wall surfaces already treated, it is necessary to treat the wall aright, making it either washable or porous, according to how the room is to be used. As room space is usually scanty, we cannot have walls which will be too easily damaged or stained during occupancy. The whole wall treatment, up to the ceiling, should be uniform. Above all, there should be no wainscots. Wood panelling is highly effective—choice woods, beautifully grained, the doors not unnecessarily large, and un framed, and simply cut out of the wood. In small rooms the ceil ing also may be executed simply in wood, a treatment which gives a good, severe, solid effect. Parquet floors, covered with self coloured linoleum or with loose carpets are often desirable; carpets are needed where the occupants are likely to spend long hours comfortably seated at ease. The carpets might be self coloured and of good material ; if they have broad or narrow stripes of dark colour marking the border, they look well and will certainly never be thought tasteless. Whatever cupboards are re quired in such a room should be built into the wall, and writing tables, etc., should be made to tilt up and disappear into the wall. Collectors will perhaps add glass cases, reaching to the ceiling, to these walls, and may even keep pictures in this way; for to use valuable pictures or statues as wall decorations is dangerous to occupants and the safety of the pictures or objects.

Heating and Lighting.—The approved method of heating to-day is by hot-water pipes, which give a fairly certain and regular warmth. As they require large radiating surfaces, on account of the not excessive warmth they impart, they might also be built into the lower parts of the wall—suitably isolated, of course. Light is best admitted through the window, hence this should be well lit up in the evenings also—perhaps by ceiling lights between the double glazing. This form of illumination will usually suffice, but a number of contact points at carefully chosen places, including some in the floor for standing lamps, etc., of the most varied types, will prove serviceable. The age of pompous lamps and chandeliers, etc., hung from the ceiling, is past ; they break up the space and blind the eye. It is important to note that candle-light burns upwards, and does not dazzle if the brilliance is not excessive. It was natural and necessary, in an age of magnifi cence, to assemble countless candles in a cluster; the flickering light, surrounded with polished crystals of glass, was capable of producing great effects. The form of illumination produced by imitation candles of frosted glass and electric lamps in the shape of flames—a lifeless copy—is one of the most incredible blunders in taste. Gaslight, as an open flame, or better, with mantle, also burns upward. Its characteristic mark is the supply of the fuel by means of pipes. The pipes must therefore be given special prominence. Electric light is used in incandescent wires ; its char acteristic note is that it hangs downward, and on a cable. This is the proper position of an incandescent lamp, and it is an abuse to place it sticking upward, for the sake of some favourite lamp. The modem age of incandescent lamps offers the most varied and origi nal combinations and will prove particularly serviceable in public localities and large apartments. The candle continues and will continue to be employed as a table illumination at meal-times, on account of its comfortable, and at the same time decorative effect.

(See LIGHTING AND ARTIFICIAL ILLUMINATION.) Colour Treatment of Walls, etc.—In deciding on the wall treatment of a room the governing factor is always its purpose or use, which should determine its form. In many rooms which are only meant to be occupied for short periods, and are made of masonry, the colour of the paint, in particular, can work wonders. A beautiful bright cinnabar red, pale yellow or green have a cheer ful effect. A deep red will certainly have a solemnizing, pale blue and grey a tranquillizing, effect. Very light brown, pink or pale violet are generally suitable for ladies' rooms. Blue is a very good colour for resting rooms and bedrooms. A white wall, as such, in a beautiful, natural material, will always remain in favour, and will invariably prove a good convenient background for furni ture and stuffs. In considering any other colour, the chief point is whether a warm tone (yellow, brown, red) or a cold one is re quired. This is where most mistakes are made; a very strong sense of colour is necessary if the whole effect is not to be spoiled by woods and stuffs which do not harmonize in colour. A new idea, which conforms with our feeling for space, is to put slashes of the colour of wall and ceiling on to the window wall. If we put in any exceptional piece of furniture, part of the wall, against which it stands, can be coloured to suit. It will sometimes be admirable to cover walls and ceiling altogether with stuff, giving an effect of warmth. It is preferable to do this first with stuffs in a single colour.

Disposition of Furniture.—We shall, then, need less and less furniture in our living-rooms, since everything put there merely for show, or, worse still, for symmetry, must vanish. The fireplace, burning wood or coal, should be retained on account of the ventilation which it affords, of the beauty of the open flames, and of its warmth in autumn and spring. The inmates of the house will love to gather round it of an evening, or in chilly weather, and this is the chief place in which seating accommodation, of varying size and shapes, is to be placed. A low occasional table, always placed beside a chair, never in front of it, and electric lamp, and perhaps a small moveable stand for books, newspapers, and possibly light refreshments, will meet all needs. As most, if possi ble, all articles of furniture should be fitted into the walls, we hardly need any more furniture in the living-rooms beyond chairs and tables, except perhaps a flower-pot for a beautiful, large in door plant. The latter should preferably be a lime or an oak, rather than a palm or anything else alien to native flora. Cut flowers in a beautiful glass or a good piece of pottery, set in the right place, give great pleasure. The first law of the decorative artist is to make life cheerful and full of joy by the simplest pos sible means. The time is gone when human beings were supposed to find pleasure in dark, cellar-like rooms with heavy carpets and festal plush curtains, innumerable ugly knickknacks such as balustrades, candelabra without lights, flowers with artificial dust to imitate the genuine, wardrobes and chests of drawers.

Bedrooms and Bathrooms.—The bedroom must be light, again with one wall all windows, the beds on simple steads of wood or metal, not unnecessarily large. The light must be behind the head, so that one can read easily, lying on either side. A roomy easy chair with a small table beside it, a footstool, small, light tables on either side of the bed on which to place books, medi cines or a glass of water, will be sufficient furniture, if we have made arrangements for everything else in the bathroom and dressing-room.

The bathroom has become increasingly important. It is impos sible to do without it, and for various reasons it is desirable to allow it ample space. It is used, not only for washing and bathing, but for gymnastics and massage and all sorts of exercises. It must allow of quick and thorough cleansing; both walls, floor and ceiling should therefore be tiled. Furniture, if any, should be of enamelled metal glazes, as in the operation room of a hospital. The walls and ceiling may, of course, also consist of enamelled metal glazes, and the colour, besides white, a very pale grey, or, for a lady, even a pale pink shade. The dressing-room may have cupboards for all purposes around three walls, with one wall wholly mirror, in front of which should be a small table for toilet articles and the like and a low, wide chair, painted in dull oil or varnished. The lighting should be built into the mirror wall on either side, the floor covered with heavy mats or carpets, as it will often be trodden by bare feet. It should be possible to see that the floor of the bathroom is warm, not ice-cold, without em ploying bath-mats. In small houses, however poor, at least a sheltered table-nook must be arranged.

Attics, Kitchen and Pantry.—The attics, kitchen and pantry, the latter next to the dining-room, should also be clean, easy to wash, and in every way practical in their arrangements. No ma chines or implements whose shapes are in any way decorative or ornate should be used. The stands for kitchen utensils should be open, the lighting from the ceiling, which, like the walls, should be covered with simple white, undecorated tiles. The floor should be paved with plain slabs, preferably in pale grey or black. Pans, jam pots, etc., are better put away in a separate niche than in a refrigerator.

Assistants must be trained to look on themselves not as servants but as colleagues. They must be lodged in a nice, cheerful room and have their own recreation and dining rooms, to avoid any feel ing of inferiority. It is advantageous, if only on practical grounds, to have each of these rooms in a different colour. Obviously there must be ample facilities for bathing and washing.

To turn to the nursery, it is well to separate the day from the night nursery. Where there are many children, a sickroom with all modern comforts would be very desirable. In the day nursery everything which might cause injury, such as sharp curves and angles, must be avoided. Special regard must be paid to the child ish habit of crawling about. Tables should be round and the edges of the surface and the feet rounded off. Toys may be kept in cupboards which can be opened easily and without danger. Walls and ceiling must be in bright colours, perhaps each with a different colour, red, yellow, green, white, the ceiling light blue and the whole decorated with small stars. A convenient low chair for the mother or governess is an absolute necessity: the cover should be bright stripes, of washable material ; the lighting again from the window wall and with convenient contact points for a port able lamp. Contacts for a wireless and cinematograph also must not be forgotten. A small darkroom for photographic purposes is desirable. In large houses a small workshop might be fitted out for the boys, to arouse their instinct to use their hands at an early age, and have a place where small repairs can be carried out.

Furniture and Craftsmanship.

The furniture in the living rooms should be chiefly of walnut and oak, and in countries with colonies, also of foreign woods such as mahogany, etc. Dyeing and staining is out of date, but inlay work, carefully prepared and used in dry rooms, has proved its value. Deal is very suitable for bent wood furniture, which is made in the following way : the wood is cut into strips, which are put into metal frames, through which steam is forced at very high pressure. In this state the wood grows so soft that it can be bent into any desired shape. This kind of furniture is often employed in offices, cafes and similar establishments for which its extraordinary cheapness, which can yet be combined with excellence of shape, fits it. Naturally, wherever possible, any other kind of wood may be em ployed if obtainable and suitable for this purpose. Nowadays metal is also often used, both bare and enamelled or painted. Abstinence from the use of machinery in making furniture, as re quired by Ford Madox Brown in 1881, is no longer practicable. The machine should be used simply as a tool; and under no cir cumstances must it imitate handwork; it should be used only on work of the type which demands no artistic impulse; e.g., the pressing and filing for inlay work under steam pressure, the trim ming and preparation of the material, etc., operations which will not distort the craftsman's work; the machine is there to save time and labour. Any unintelligent work can be replaced by the proper appliances. The shape produced by machine work must be quite distinctive, to allow a proper appreciation of its peculiarities. It is certainly wrong to make use of machinery to produce large quantities of ugly objects, with its accompanying waste of ma terial. It is not absolutely necessary for us to produce everything by handwork, nor is that the sole criterion of value, but it is ab solutely necessary that machine productions should be well thought out—high-minded, in fact, but not deformed and obscured by un suitable decoration. An inventive brain and good planning and design will always re-discover beautiful form. Detection of servile imitations will always allow real talent to accomplish work of value. This point is of the greatest value even from the economic point of view, when we consider that even to-day in many coun tries, valuable material is rendered valueless by bad workmanship, whereas right treatment could only enhance its value and so make life more precious and sanctified. Only beauty, beauty every where, can further exalt our modern life and make us happy. There ought to be a movement, similar to that of the Church, to follow these ends and declare war on all bad methods of work. The great talents many of which live and perish to-day unnoticed would suddenly awake to life and create works of undreamed of grandeur, as of yore. It is this spirit, together with a universal ity of understanding and co-operation, that is the great lesson of the past ; not bad imitation, which inhibits and destroys fresh ideas. The fact is that to-day we in Europe no longer have any conception of the mysterious forces of the old workshops, which yet produced work that was always good—sometimes outstand ingly good. What was the social position of those men in com parison with the organised world of to-day? Our chief interest lies in the men who lived and worked in the period between the great migrations and the mid i 8th century. How could that extraor dinary unity arise between palaces, castles, churches, city halls, even whole cities and whole villages—a unity complete down to the smallest detail, and crystallising into clearly defined styles? Art follows no law. It can only spring from deep spiritual move ments, and the greatness of it is the mirror of the greatness of an age. It penetrates into the smallest mountain hut, whose simple, unsophisticated shapes are equally a reflection of the spirit of the age. To-day we are learning to appreciate increasingly the un sophisticated work of these simple men ; it is a revelation to us, as is the work of the modern child. The essential in old times lay in the wonderful work fashioned by master craftsmen in excellent workshops. It may have been the year long community in work and creation. The blossoming of childhood in good sur roundings. The complete mastery of the handicraft and the joy of producing something ever new, ever more fully perfect. The only external impulse in those days came from strange pieces of booty brought home by knights from the wars, and through the co-operation of masters who had been carried off in captivity. These masterpieces blend in natural wise with the native works, and new, mysterious creations issue. In those days there were no workmen, only masters and apprentices. The work, design and execution, sprang from one force and was therefore created with a love unknown to-day. Based on a great tradition swayed and inspired by universal sympathy, men were ever inventing some thing new, either in form or in better work, striving towards the highest perfection. The clumsy apprentice was mocked and cast out, the skilful admired and encouraged. To watch the life of his fellows from childhood in the workshop was for the layman the best education, to train him to become a true and appreciative connoisseur.There may still be workshops of this sort to-day; the tailor's workroom, perhaps, comes nearest to it. Let us consider a moment where their true value lies. Something is sewn, for example, with a machine invented on the grand scale, superior to handwork chiefly in accuracy and regularity. Superior except in one point, the feeling for material. Once set in motion, the machine can only work on mechanically, and so must fail wherever attentive hand-work, inspired by mind and feeling, takes account of every difference, however small, and thus gives even greater steadiness, being therefore better in quality and so also creating greater value.

Complete recognition of the task and unshrinking performance of it must lead to a new style. While the first necessity is the simple, unadorned form, we need have no fear of genuine talented enrichment. Talent will always find the right way by instinct, and need not shun the most complicated shape. Finally let it be said that where for any reason a richer shape is preferred the forms created must always be new and natural. Repetition of old forms, old styles that have already had their day, is simply ruinous. It is equivalent to a confession of poverty of ideas and destroys all natural understanding and enjoyment. At the Con gress of modern bridge building in Vienna, Sept. 1928, the presi dent, Dr. Otto Linton, of Stockholm, treated this question at length, declaring that the architect was now a back number, and had been replaced by the engineer. He sees in the architect, the decorator who sticks pointless rosettes into purposeful building— a misrepresentation of the artist's real role, which consists in giving expression to the requirement-plan, and order to the pur pose-form. He will always find aim and purpose for his work in satisfying fully the needs put forward by the builder, think in good proportions and rightly chosen material and express himself through these, and not through ornaments stuck on at random.

Style cannot, as Linton says, be dictated by the brain of the mathematician or the blue pencil ; it springs from the character of a nation. The determining factor is whether that character is natural or corrupt, crude or refined, and whether it has advanced to the stage of seeing and preferring the better. It will never be possible to make exact calculations regarding colour, and yet colour is one of the most important factors in modern build ing and decoration. It would be equally foolish to say that artistic painting is a back number to-day, varnishing and distemper alone required. The only true measure is to appreciate the value of modern painting, feel its quality and estimate that alone. The essential is not even the individual species within modern painting —although this, too, certainly needs to be considered, but solely the significant side and special quality within a capability. We see this best in photography, which can be splendid or absolutely uninteresting, according to the amateur who handles the camera. The main point is therefore to re-educate ourselves so far that we can choose the right forces in every field and allow only great capacities to influence us. The more true forces assert themselves, the higher will be the cultural level of a people. The work of the engineer is much less cramped than that of the architect, hence his untiring development, particularly in all creative fields. Respect for the achievement is still intact, and the success is consequently greater.

Business Premises.

In fixing our business localities, consid eration must be paid both to absolutely economic and purposeful arrangement and also to advertising effect. The principal problem is again that of material, colour and lighting ; but the wares on sale must also be good.As for the cinematograph, the first requisites are good, com fortable seating accommodation and easy entry and exit. Tip-up seats covered with good leather, a good carpet on the floor (if possible of the same colour as the leather) ; the walls preferably hung with stuff, and similarly all curtains, partitions, etc. made of the same material, will give a good effect. An efficient system of ventilation and perfect lighting (q.v.) (preferably by means of soffits), for the intervals, is required. Particular attention must be paid to the vestibule, as this is very much used. Marble or inlaid wood are both suitable materials. If the till and the buffets are made automatic, great simplification in running will result. If the rooms are given convenient shapes, the staff can be re duced. In cinematographs and the like special attention must also be paid to securing the electric cables. They are best laid in the walls; but it is advantageous for the purpose of repairs, to have them easily accessible. The cables must therefore either be laid in grooves in the walls, or stretched free, absolutely taut ; for the frequent, untidy crooked laying and fastening is dangerous as well as ugly. Absolutely perfect fixing is the first duty. The last word on this point has not yet been said. It is best if the cables can be fastened without visible screws, for screws are always a makeshift. Otto Wagner declares permanence to be the first law of all architectural expression. This calls for good material and excellent work well planned and designed. To achieve this, re quires constant practice and the possession of a natural capacity of identifying oneself with one's task. For example, in decorating and fitting a butcher's shop. Our immediate thought is to cover walls, ceiling and floor with a material which will keep cool and can be washed, therefore tiles are used. In old days we should have wanted to adapt it to Roman precedents; to-day we invent good fittings, avoid all ornamentation, but put the signs in the right place, and in perfect lettering. The lettering, which is usually a disturbing element, has assumed particular importance to-day.

There have always been certain objects which accurately reflect our age, and a later age will find it easy to recognize in these the forms in which we express ourselves. This is especially relevant to the coach-work of motors and modern carriages, rolling-stock, aeroplanes, etc., and many machines, if designed solely to express their purpose and not marred by antique decoration. The arm chair, too, has been altered and adapted to suit modern require ments, solely on practical grounds. The interior fitments of many theatres, hotels, restaurants, cafes, cabarets and bars must be described as quite new and successful. The equipment of ocean liners, especially in the working parts, is also modern, even though here, as with the American sky-scrapers, an absolutely modern construction is often spoiled by incomprehensible, antiquated decorations.

Materials and Ornaments.