Hydrozoa

HYDROZOA. The Hydrozoa (sometimes called Hydromedusae) are a class of ani mals, the vast majority of which are marine, and which belong to the still greater assemblage known as the Coel• enterata (q.v.).

The Hydrozoa include not only polyps, but also medusae or jellyfish (these terms are defined in the article COELENTERATA).

They are, in fact, that group of Coelenterata in which neither the one nor the other of these two forms of body predominates, and in this respect they contrast strongly with the other main classes (Scyphozoa and Anthozoa). Moreover, both polyp and medusa have a simpler plan of structure than in the other classes. The polyp itself is frequently (though not always) small. Its mouth leads directly into the internal cavity of its body (coelenteron), without the intermediary of a definite throat or gullet of any kind, and the ectoderm and endoderm (see COELENTERATA) meet at the lips. The coelenteron is a simple cavity lined by endoderm; it is not subdivided by partitions into lesser cavities, nor does it contain definite organs of any kind. With these limitations the actual form of the polyp varies very greatly. The medusa pre sents infinite variety of form, but it too lacks a throat, and al though its coelenteron sends out radiating canals which run from the central cavity through the solid tissues of the bell, it is other wise simple in that it contains no definite organs. The medusae of Hydrozoa are generally speaking smaller and more slightly built creatures than the medusae belonging to the related class Scyphozoa, although in certain cases they attain a larger size than the average, which is a matter of millimetres. The Hydrozoa are also characterized by the fact that the sex-cells, when they ripen in the clusters known as gonads, typically lie in or under the ectoderm, although the site of their original formation may be in either ectoderm or endoderm.

It is among the Hydrozoa above all other Coelenterata that the phenomenon, briefly characterized elsewhere (article COELEN TERATA), and known as polymorphism, attains its height. The details of this condition are described in parts of the present article and a summary of the question is given after the section on Siphonophora.

The infrequency of brackish or freshwater forms among the Coelenterata makes their occurrence of interest. The ordinary marine Hydrozoa are either pelagic (swimming or floating organ isms) or sedentary, according to their nature, and many of either kind exist. The brackish and freshwater forms exhibit the same diversity, though few in number. One of the most interesting is a minute creature, Protohydra, the length of which is about 3mm. This organism inhabits the surface-layer of mud, rich in diatoms, which is to be found in the bottom of pools in certain tidal marshes; it also occurs in oyster-beds and similar places. It is carnivorous, and reproduces freely by transverse fission, but its sexual mode of reproduction is unknown. It possesses no ten tacles, and is as simple in structure as any known Coelenterate.

The best known of the non-marine Hydrozoa, however, are the genera Limnocodium, Limnocnida, Cordylophora and Hydra. Of Hydra more details are given below, and the chief interest of Cordylophora lies in the fact that it may flourish in water of different degrees of salinity as well as in fresh water; it is other wise ordinary. Limnocodium ryderi possesses a feebly developed polyp-generation (up to about 2mm. long) which produces small colonies containing about 2-7 individual polyps without tentacles. These colonies can produce buds of two kinds; some become separated from the parent, form polyps and produce new colonies, others develop into medusae, and these are liberated and swim away. The species of Limnocodium (with which is now included Microhydra) are not very clearly recognized; but representatives of the genus occur in lakes, mill-streams and similar places in the United States, Germany, China and Japan, and have appeared in water-lily tanks at various botanic gardens, and in other tanks and aquaria. The genus Limnocnida contains medusae which have been found in several river-systems in Africa and in some of the great lakes, as well as in India.

The Hydrozoa comprise three large orders which from this point onward will be treated separately.

The Hydroida are, roughly speaking, those Hydrozoa which possess a definite alternation of the polyp and the medusa in their life-history, and in which one generation (the polyp) is sedentary and usually constructs a fixed colony, the other being free-swimming when fully developed. There are various excep tions to this general statement, but they are not characteristic of the group as a whole. The variety of form and life-history ex hibited, however, is so great, that it will need detailed treatment. It is convenient to begin with the consideration of the common and well-known but quite untypical freshwater genus Hydra (fig.

1),

which is the only thoroughly successful freshwater Coelen terate. Hydra, of one species or another, occurs in ponds and ditches and similar situations in many parts of the world. It consists of small isolated polyps, each with a pillar-like body and a limited number of tentacles. The length of the body is a matter of millimetres, and the tentacles in some species may be longer when stretched out than the body, although both they and the body can contract into rounded knobs. The Hydra attaches itself to stems and water-weeds, or floats beneath the surface film. It catches prey, of ten of a large size compared with its own bulk, in the manner characteristic of the Coelenterata (this is described in the article COELENTERATA) by stinging and then swallowing it.From the body of the Hydra there grow out buds, each of which acquires tentacles of its own and ultimately becomes sep arated from the parent ; but no medusae whatever are produced, this being quite exceptional among the Hydroida. There are usually developed separately, on different parts of the body, ova ries and testes which give rise to the sex-cells. Whether this repre sents a degenerate condition, and there was once a medusa-stage in the life-cycle, or whether it is a primitively simple condition, can not be determined.

The few other simple genera which are known, such as Proto hydra, may be related to Hydra, or may be primitive or degener ate forms of separate origin. With the above preliminary, the characteristics of the group as a whole, without reference to these special forms, may be considered.

Structure.—The following is a description of the structure of a typical Hydroid, provided by the genus Obelia (fig. 2). Obelia begins its life, after the embryonic stages which succeed fertil ization of the egg have transpired, as a single polyp, possessing a number of simple tentacles in a circlet around the base of its conical peristome or manubrium. The polyp sends out roots which attach it to the surface of a stone, the frond of a sea-weed, or other suitable support, . and grows a stalk which raises it some what in the water. From this stem a bud arises from which, although it is at first a mere knob, a new polyp is gradually de veloped. This process of growth proceeds in a definite and regular manner, until a small tree-like colony, from less than an inch to several inches in height, is formed; the branches are definitely arranged, and all bear polyps. If one of the colonies be examined in detail, it will be found that each of the polyps possesses, outside its body, a little transparent cup of relatively stiff, horny material, into which it can withdraw when alarmed; and that not only are the polyps connected with each other by a stem composed of soft tissues, but the cups also are connected by a horny layer, outside the soft stem, which stiffens and sup ports the latter. The cups are known as hydrothecae, the soft stem as coenosarc, and the horny layer (including stem and cups) as the perisarc. The new polyps develop only from the tips of a branch of coenosarc, and not from one another; and in a well developed colony it will be seen that some additional branches have grown out, mostly in the lower part of the colony, each of them similar in structure to a developing polyp, and usually re garded as representing one. These branches (known as blasto styles) do not develop a mouth and tentacles; instead each produces a number of buds which gradually develop into small medusae, and which are known as snedusoid buds. The blastostyle, like an ordinary polyp or hydranth, has a covering of perisarc known as a gonotheca, but this is at first imperforate. In due course it becomes open at the end, and the medusae separate off from the blastostyle and swim away into the sea, where, of t€ i a period of free life, they become hydroid polyps.

The structure of one of these fully developed medusae must now be considered in more detail (fig. 3) . The body has the form of an umbrella, with a manubrium similar to that of a polyp hanging down inside it and bearing the mouth at its end. The manubrium is lined by endoderm, and contains a cavity, the main part of the coelenteron. The stance of the umbrella consists of mesogloea with ectoderm on both external surfaces; but the layer of mesogloea is penetrated by four narrow tubes or canals, lined by endoderm, which run out from the base of the manubrium like the four arms of a cross. necting these radial canals with each other is a flat sheet of derm like a web (endoderm ella) and also a circular canal which runs round the edge of the umbrella close to the bases of the tentacles. The latter are solid, both in medusa and polyp. At the edge of the bell, on the inner side of the ring of tentacles, is a little circular shelf (the velum) which projects inwards and slightly rows the opening of the bell. Round the margin of the bell, at the bases of certain of the tentacles, lie the sense organs, minute sacs, formed by the ectoderm, and each containing a calcareous ticle (the statolith). They are known as statocysts (fig. 5), and are eight in number, two being definitely placed in each of the quadrants between the radial canals; they probably initiate and control the swimming-contractions of the bell. The sex-cells of the medusa ripen in the ectoderm of four gonads which occur on the course of the four canals, and which, when ripe, shed their products into the sea. The fertilized eggs develop into new polyps which initiate fresh colonies.

The story of Obelia is typical of the Hydroida, with modifica tions of one kind and another. In some cases the polyp-generation includes a single nutritive individual only, but usually it forms a colony. The form of the individual polyps and medusae, as also that of the colony, undergoes great modification however.

The polyps sometimes possess cups of perisarc as does Obelia; but often they are without these.

Their tentacles are sometimes simple, sometimes knobbed at the tip or branched ; sometimes ar ranged in one circlet, sometimes in two (one round the lip, one at the base of a conical manu brium), in other cases arranged irregularly over part or most of the surface of the polyp.

The medusae vary even more than the polyps, both in shape and structure, and some idea of the diversity which occurs among them may be gained by reference to figs. 2-4 and 7-8. The shape of the bell may be shallow or almost flat, or on the other hand may be a high dome, and natu rally varies with the movements of the animal. The number, ar rangement and structure of the tentacles is widely various. The living medusae are some of the most beautiful of marine creatures. Their transparency, which is often touched with definite colour in given parts, and the regularity of their structure are responsible for this, and in some cases their movements also are extremely grace ful. The sense organs vary from one kind of medusa to another. Statocysts are present in a number of cases, and these exhibit vary ing degrees of complexity of structure, with this in common to all of them—that the epithelium of the statolithic sac or pit (for the simplest of statocysts consist of an open pit) is derived from the ectoderm, and no endoderm takes part in its formation. Many medusae possess sense-organs of another nature, known as ocelli, and these are sensitive to light. In their simplest condition they consist of a clump of sensory cells mingled with pigment cells; but the more complicated ones possess a definite lens. These ocelli may be situated close to statocysts, but many medusae possess ocelli only, and others statocysts only. Another impor tant variation in structure is, that in some medusae, as in Obelia, the gonads are situated on the radial canals ; but in many others the sex-cells ripen instead on the manubrium.

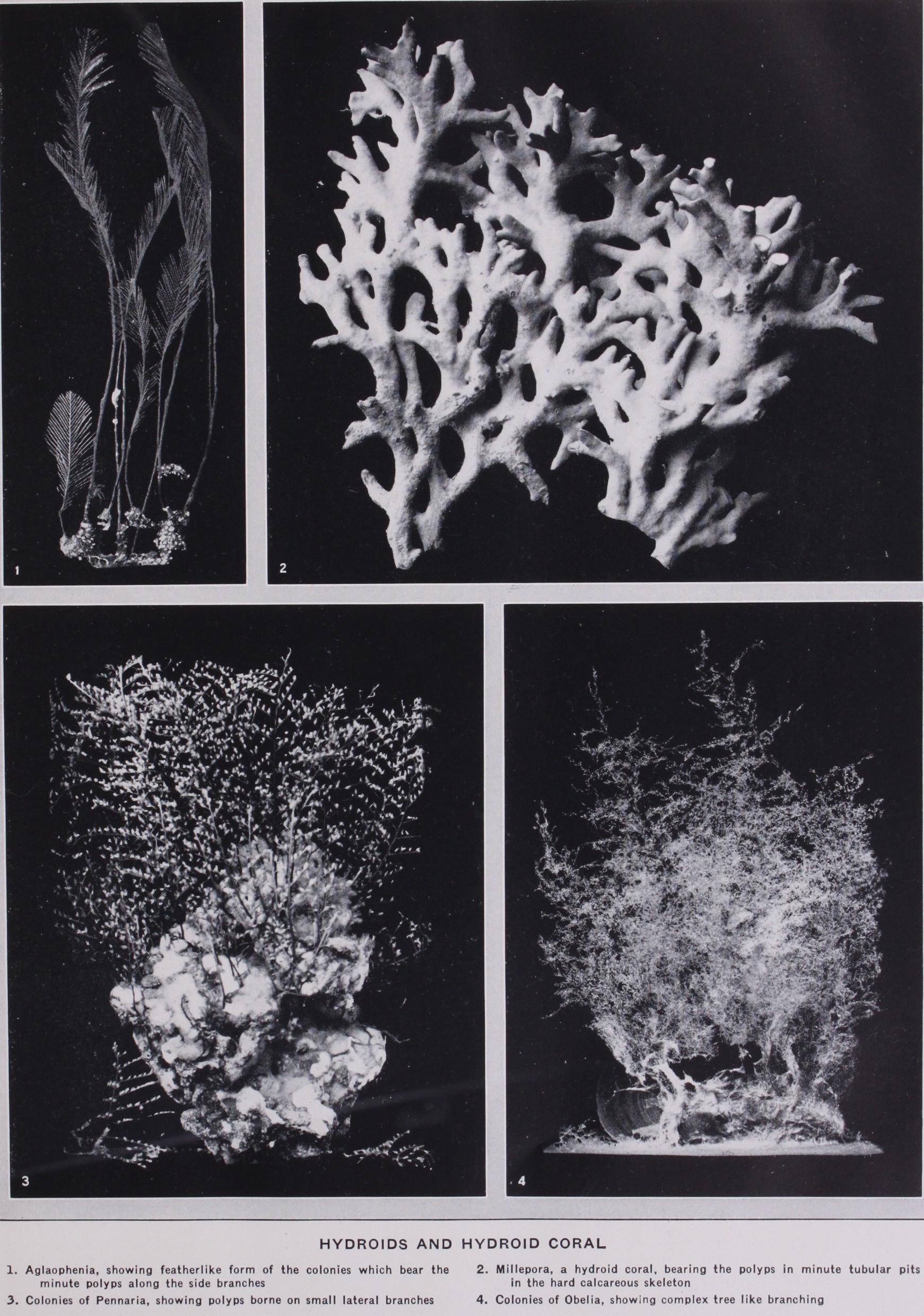

Colonies.—The next consid eration must be that of the kinds of colonies which Hydroids con struct. These colonies are fre quently small and relatively soft, the horny perisarc giving a con siderable amount of support, but not constituting a really rigid skeleton. Many such colonies are an inch or less in height, although colonies several inches long are common. Only rarely does the colony become actually large, but in a few cases it achieves a size and solidity which give it rank with the reef-forming corals; in these cases the skeleton is massive and calcareous, and is in fact "coral." Hydroid colonies are roughly speaking of two kinds—mat-like and tree-like structures. The mat-like forms consist of a network of rootlets, attached to a stone, sea-weed or other support, from the upper surface of which arise the polyps. The network is sometimes straggling, sometimes compact, and may form a con tinuous sheet. The tree-like forms are mostly delicate feathery structures, resembling rather the fronds of a finely divided sea weed than any animal. The general aspect of some of them is shown in the accompanying Plate. The size of the whole colony, the exact way in which it branches, and the way in which one polyp after another is added upon a branch, affect the general appearance of the ultimate result. Sometimes the branches them selves are thick and are composed of a dense network of branching rootlets (Clatjirozoon, fig. 6), the polyps projecting at the surface. This condition, which is achieved in a manner different from that which produces the average tree-like colony, leads on to the state of affairs found in the massive, limy colonies.

These massive forms deserve special mention. They have been considered in time past as a separate group of Hydrozoa, the Hydrocorallina; but it has become evident that they are simply Hydroids with a more than usually solid skeleton, and that some of them are probably related to one series of Hydroid ancestors, others to a different series. A good example of these creatures is found in Millepora (see Plate). This animal constructs a colony containing innumerable minute individual polyps, which are connected with each other by a continuous surface-sheet of ectoderm and by a network of ramifying tubular rootlets. The colony secretes a massive, limy skeleton which may become a foot or more in height, and which is branched somewhat like the antlers of a stag, but in more compact fashion. The polyps inhabit little pits in the surface of the skeleton, and can retire into these com pletely when alarmed. The network of rootlets is lodged in a network of canals in the surface layers of the skeleton, the deeper parts consisting of coral only and containing no soft parts; this internal portion was secreted by the soft parts originally, but as growth proceeded and further skeleton was formed, these retired to the surface-layers. One can imagine that a similar state of affairs would be produced if a colony such as that of Clathrozoon were to secrete limy material into the meshes between its net work of rootlets. Millepora is extraordinarily interesting in one respect. When the time comes for sexual medusae to be pro duced by the colony, these are not formed from buds as in Obelia and other Hydroids. Instead the sex-cells, which are migratory, move from the rootlets into one or other of the polyps. Each polyp so affected loses under their influence its characteristic structure, and becomes trans formed by degrees into a medusa.

The pit surrounding it enlarges and becomes closed in, so that it forms a cavity cut off from the outer world, and until the medusa is ready to escape it remains so ; finally the cavity opens again and the medusa comes out. It is a weak swimmer and cannot feed; it swims a very little distance before shedding its ripe eggs or spermatozoa, the union of which gives rise to a polyp so that the life-cycle begins once more.

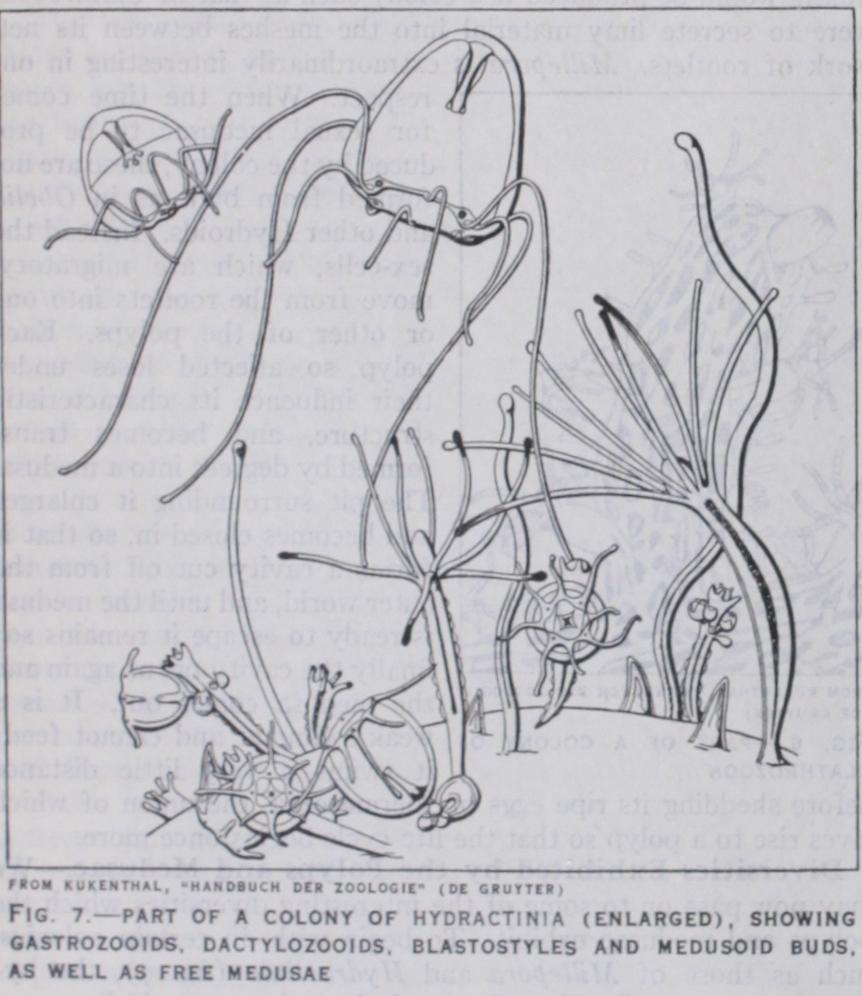

Diversities Exhibited by the Polyps and Medusae.—We may now pass on to some of the interesting diversities which the polyps and medusae exhibit. To begin with, in certain colonies, such as those of Millepora and Hydractinia (fig. 7), the hy dranths are not all alike. Some of them (gastrozooids) possess mouths as well as tentacles, and inside these polyps digestion of food takes place. Other polyps on the contrary possess no mouths, but may have tentacles and are well provided with stinging capsules such as are described in the article COELEN TERATA. These polyps themselves cannot feed, but they play a defensive part in the colony and assist the others in the capture and paralysing of food; they are known as This is a simple example of the phenomenon of polymorphism, which has been previously mentioned and which will be further dis cussed later. It is carried to greater lengths in Hydractinia than in hiillepora, since in this case the colony produces also blasto styles similar in principle to those of Obelia. These may be re garded as modified polyps with a body but without mouth or tentacles, which produce sexual buds. Therefore a Hydractinia colony possesses four kinds of individuals—gastrozooids, dactylo zooids. blastostyles and sexual buds.

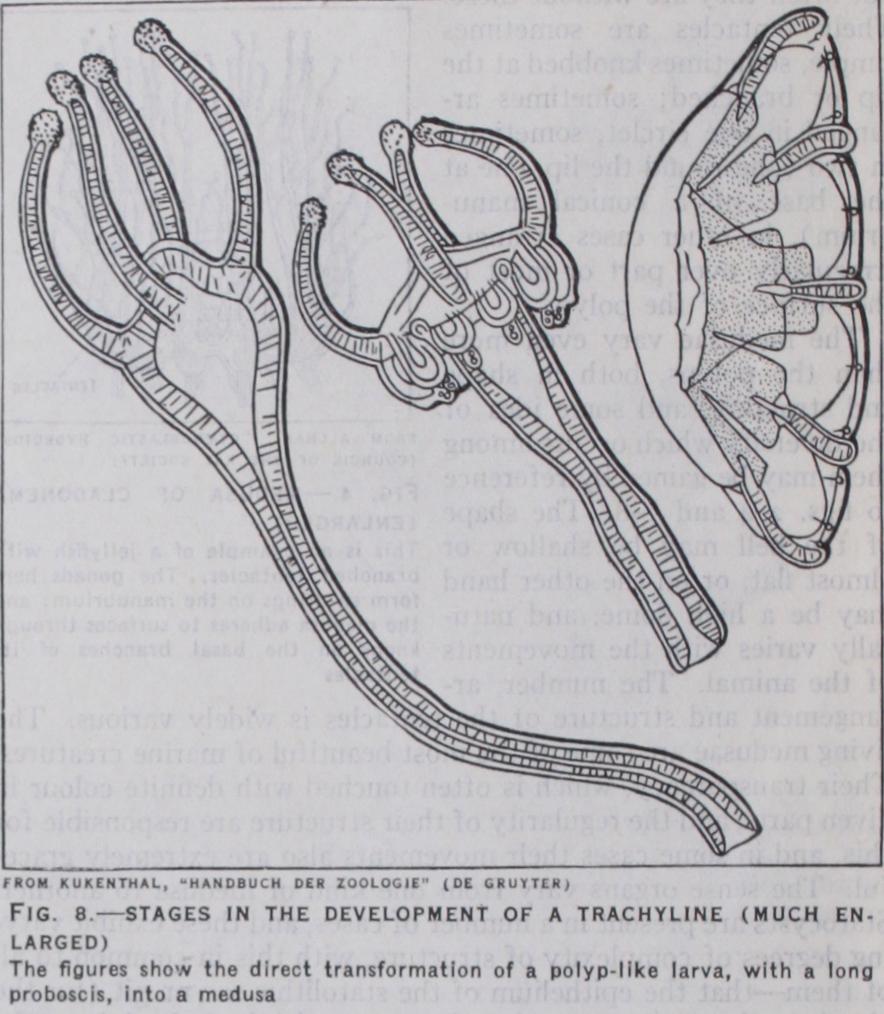

To turn to the medusae, we rind here a most curious state of affairs. To begin with, medusae may arise from blastostyles or direct from ordinary polyps; and the blastostyles may arise from the root or stem of a colony or from a polyp itself. Moreover, a medusa may itself bud off others from its manubrium, or from its tentacle-bases or other parts. The most remarkable fact con nected with the medusae, however, is that despite the fact that a medusa is obviously an advantageous development, in that it can swim away and spread the eggs and spermatozoa over an area vastly wider than they could otherwise reach, there is yet a strong tendency among the Hydroida towards a condition in which the medusa not only remains permanently attached to the colony whence it sprang, but also becomes much reduced and simplified in structure. A series of medusae can be traced, in which at one end there is found the fully formed free-swimming jellyfish, at the other end a degenerate sac-like structure, devoid of any medusa-like features, and resembling the gonad of an active medusa, such as that of Obelia. This degenerate formation, which remains attached to the colony, is known as a sporosac, and con sists of a layer of ectoderm containing or covering the sex-cells, and surrounding an endodermal core. Between these two ex tremes all intermediate stages may be found.

It has been considered by some authors that the sporosacs represent, not a reduced but a primitive condition, and that the other stages are to be regarded as developments leading up to Lhe fully formed medusa. This would seem reasonable from the point of view that the roving medusa is an obvious gain to a fixed colony; but the facts of the case do not seem to support it. From the structure and mode of occurrence of the various grades of medusae, and from the fact that in the development of certain of the reduced forms, medusoid features appear for a time and are subsequently lost, it is judged that they are not primitive but degenerate. The precocious development of the sex-cells may be the factor which leads to the reduction of the medusae; the gain being increased fertility.

The Coelenterata are singularly free from parasitic members. Of the few that are known, one is particularly interesting. This Hydrichthys boycei, a species referred to the Hydroida but which may be an unusual siphonophore. The colony is one of the mat like kind, and the mat, instead of being affixed to a stone or weed, is attached to the fins or body of a fish. The underside of it sends roots into the integuments of the fish, and under its growing edge are cells which are able to destroy the surface of the fish's skin and expose the vascular layer beneath. The polyps, which have no tentacles, bend down over the edge of the mat, apply their mouths to the wound made by the latter, and obtain blood from the vessels of the fish. Another parasite, better known than Hydrichthys, is Polypodium; this is parasitic at one stage of its life in the eggs of a sturgeon, which it destroys.

Classification.

The classification of the Hydroida is instruct ive, though as yet imperfect. The connection between medusae and polyps was at first not understood by naturalists, since it could not be deduced from observation of one of these types only, without a study of the whole life-history. Even now there are polyps and medusae which have not yet been linked on to their corresponding alternative form. Consequently a double classifi cation has grown up, dealing with the two sets independently, and the two systems can be correlated with each other so far as the inter-connections are known.The polyps are divided into:— I. Gymnoblastea. Here the polyps are not enclosed in cups of perisarc (hydrothecae), nor are the blastostyles enclosed in gonothecae.

2. Calyptoblastea. Here the polyps possess hydrothecae and the blastostyles gonothecae.

The medusae are classified as follows:— I. Anthomedusae. Medusae in which there are no statocysts (though there are usually ocelli) and in which the gonads develop on the manubrium. These are the medusae belonging to the Gymno blastic polyp-generation.

2. Leptomedusae. Medusae in which there are typically statocysts and sometimes ocelli, and in which the gonads are arranged on the radial canals. These medusae belong to the Calyptoblastic polyp-generation.

In the above scheme Hydra and its relatives would be con sidered Gymnoblasts by some authors, by others they would be placed in an independent group, the Hydrida. The affinities of Limnocodium and Limnocnida are somewhat uncertain.