Iguanodon

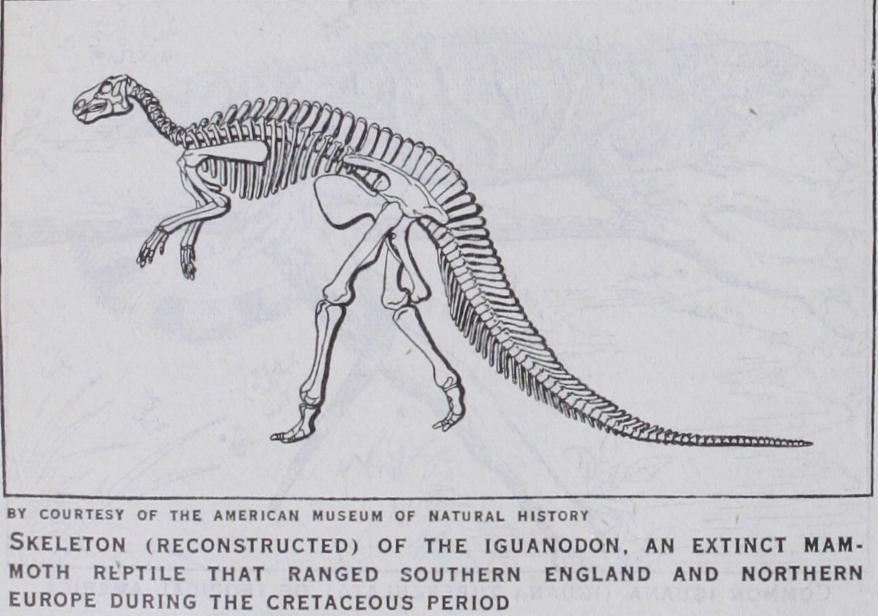

IGUANODON, a large extinct amphibious reptile. Its re mains were first discovered in the Wealden (Lower Cretaceous) estuarine deposits of Sussex by G. A. Mantell, who named it Iguanodon, in allusion to the resemblance between its teeth and those of the lizard Iguana of tropical America. In 1877 several nearly complete skeletons now in the Royal Museum of Natural History at Brussels, were found in the Wealden rocks near Mons, Belgium. More recently another nearly complete skeleton, now in the British Museum, was found by R. W. Hooley in the same rocks at Atherfield in the Isle of Wight. Iguanodon is interesting as being the first gigantic extinct reptile which it was attempted to restore by comparison with a modern lizard. Mantell's early restoration proved a failure, because it was unknown at the time that this reptile belonged to an extinct order, Dinosauria (q.v.), which differed from all modern reptiles in having limbs adapted for supporting the body when at rest, and in having more than two vertebrae fused together to form a sacrum above the hind limbs like the sacrum of birds and mammals. Like nearly all the more active dinosaurs, it had comparatively large and heavy hind quarters, passing into a long tail ; and footprints show that it walked only on its hind limbs, using the tail for balancing the fore-quarters.

The typical species, I. mantelli, is from 5 to 6 metres long, and must have measured about 4 metres in height when standing up right. The largest known species seem to have been sometimes z o metres long. The head is relatively large, laterally compressed, and about twice as long as deep. Its long axis is bent downwards for cropping its vegetable food. The front of both jaws is tooth less and must have been covered with a horny beak. The lower half of the beak is supported by a separate "predentary" bone. The edge of each jaw further back bears a single row of teeth, which differ from those of all existing reptiles in being often worn down to stumps by mastication. Under the teeth actually in use are numerous successional teeth. The neck and front half of the back are made flexible by ball-and-socket joints between the verte brae. The front half of the tail is deep and laterally compressed, evidently for swimming. The small fore-limbs must have been very mobile, and the thumb in the five-fingered hand is reduced to a bony spur. The supporting bones of the hind-limbs are much like those of ostriches, though they differ in never being fused into one mass. The three toes of the heavy hind-foot are so much like those of birds that the fossilized footprints were originally mistaken for those of birds. The body lacks armour, but the skin was hardened with a close covering of small irregular tu bercles. Footprints are common on the Wealden sandstones of Sussex, and several series have been observed without any trace of the forefeet and rarely a mark of the tail.

Nothing is satisfactorily known about the possible ancestors of Iguanodon, and few of its closely allied contemporaries have been discovered. The comparatively small Hypsilophodon, which occurs with it in the Wealden of the Isle of Wight, differs in having the teeth extending to the front of each jaw. The equally small Psittacosaurus, from rocks of nearly the same geological age in Mongolia, has the toothless front of the jaws shaped almost like the beak of a parrot. The successors of Iguanodon, the Tra chodontidae, in the Upper Cretaceous, were more adapted for aquatic life, and their toothless beak was shaped almost like the end of the bill of a duck. The side of each jaw bore a powerful grinding dentition, several rows of teeth being in use at one time. Many of the trachodonts were peculiar in exhibiting a bony crest on the top of the head.

See L. Dollo, Bull. Mus. Roy. d'Hist. Nat. Bruxelles (1882-84) ; R. W. Hooley, Quart. Journ. Geol. Soc. (1925) ; also a special Guide published by the Royal Museum of Natural History, Brussels.

(A. S. W.)