Impressionism

IMPRESSIONISM, a term applied to certain anti-academic and anti-romantic tendencies in late i9th century painting, advo cated and carried into effect by Edouard Manet, Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, Edgar Degas, and a number of lesser men who followed the example set by these leaders. Originally the word Impressionism was coined by a journalist as a term for opprobrium in a derisive criticism of a painting by Claude Monet, called "Impressions," the actual subject of which was a sunset. This work was shown in 1863 in a special room known as the Salon des Refuses, together with many other paint ings by artists who, like Monet, had suffered from the uncompro mising hostility of the Salon jury to all originality and experi mental enterprise, and who had risen in revolt against the placid self-righteous attitude of the French official Salon. The opening of the Salon des Refuses was due to the direct initiative of the emperor Napoleon III.

As a matter of fact, unlike the English Pre-Raphaelites, who deliberately banded together, chose the name for their association, and formulated a set of theories and a programme, the so-called "Impressionists" of the '6os were a number of individual artists thrown together by force of circumstance, and held together by their spirit of revolt against the tyranny of the school.

If there is any general aim to he traced through the various manifestations that have become known as Impressionism, it is the substitution in art of transitory appearance for permanent fact. The Impressionist paints things as they appear at any given moment and not as they actually are according to his knowledge of their permanent form and colour. Thus, if the contour of a figure or object happens to be obliterated or blurred by shadow or distance, he will render the undefined masses of shadow or the blurred silhouette as they are reflected on his retina, and not endeavour to give them the definition which his knowledge tells him lies hidden beneath the momentary appearance. In the same way he will record the modifications of colour caused by inter vening atmosphere and by reflection. Green foliage appears blue in the distance, shadows are not neutral greys or browns, but par take of and are modified by the colours of the surroundings; a ridge of mountains against a light sky does not appear as a sharp silhouette, but an interchange of rays produces a radiating zone connecting the light and dark masses; the rays of the sun on a clear day, setting behind a tree or a hill, seem to eat into the forms behind which the fiery orb is sinking; and, above all, there is in nature a vibrant movement of light, for the rendering of which the Impressionists have tried to develop an adequate formula.

The research work of the scientists Helmholtz and Chevreul, establishing the wave movement of light and sound and the theories of the solar spectrum happened to coincide with the Impressionist experiments and, no doubt, contributed towards the Impressionist technique of "divisionism" or "vibrism," as it came to be called in its later and more scientific phase. It is quite likely that the influence of the scientists upon Monet, the originator of the Impressionist technique, has been overrated, since the beginnings of divisionism can be traced to Watteau and Chardin and Turner. Indeed, there is no question that Monet, who paid repeated and lengthy visits to England, was as deeply impressed by Turner's achievement, as Delacroix, a generation earlier, had been by Constable's, and that he followed his natural impulse rather than scientific theory.

The technique of Impressionism followed the doctrine that colour, as a definite quantity, does not exist, but is only the result of the play of light upon form. Even shadows are deemed to be, not the negation of light, but an altered form of it. By the rigid exclusion from the palette of all but the actual colours con tained in the spectrum, and the placing of dabs of alternating colours upon the canvas, instead of mixing the required tones upon the palette, the Impressionists invested their paintings with a degree of luminosity and with a vibrant quality suggestive of atmospheric vibration that had not previously been obtained by any other method. Light thus became the real subject of pictorial art, and anything was deemed worthy of representation so long as it afforded an opportunity for recording the effect of light upon nature. Thus Monet painted his famous series of "Hay ricks," noting the appearance of a hay-stack at different hours of the day and in varying conditions of light, changing the canvas from hour to hour, to take it up again when the conditions happened to be identical. In this pursuit of light and atmospheric vibration, substance was in danger of being altogether sacrificed to surface appearance, and design was not always given due atten tion, although the Impressionists were by no means as haphazard in their manner of composition as they were accused of being by their detractors.

Parallel with this technical innovation came the Impressionists' revolt, led by Manet, against the academic canons of beauty. It was inspired by passionate interest in actuality, that is to say in contemporary life and manners, and was closely akin to the literary movement led by Flaubert, the Goncourts and Zola. Now that the Impressionist battle, which at the time aroused so much bitterness, belongs to past history and can be viewed in right perspective, it is quite clear that the alleged revolutionaries of the '6os and '7os were in reality the champions of the best tradition, and that their art was deeply rooted in the art of the past.

Manet.

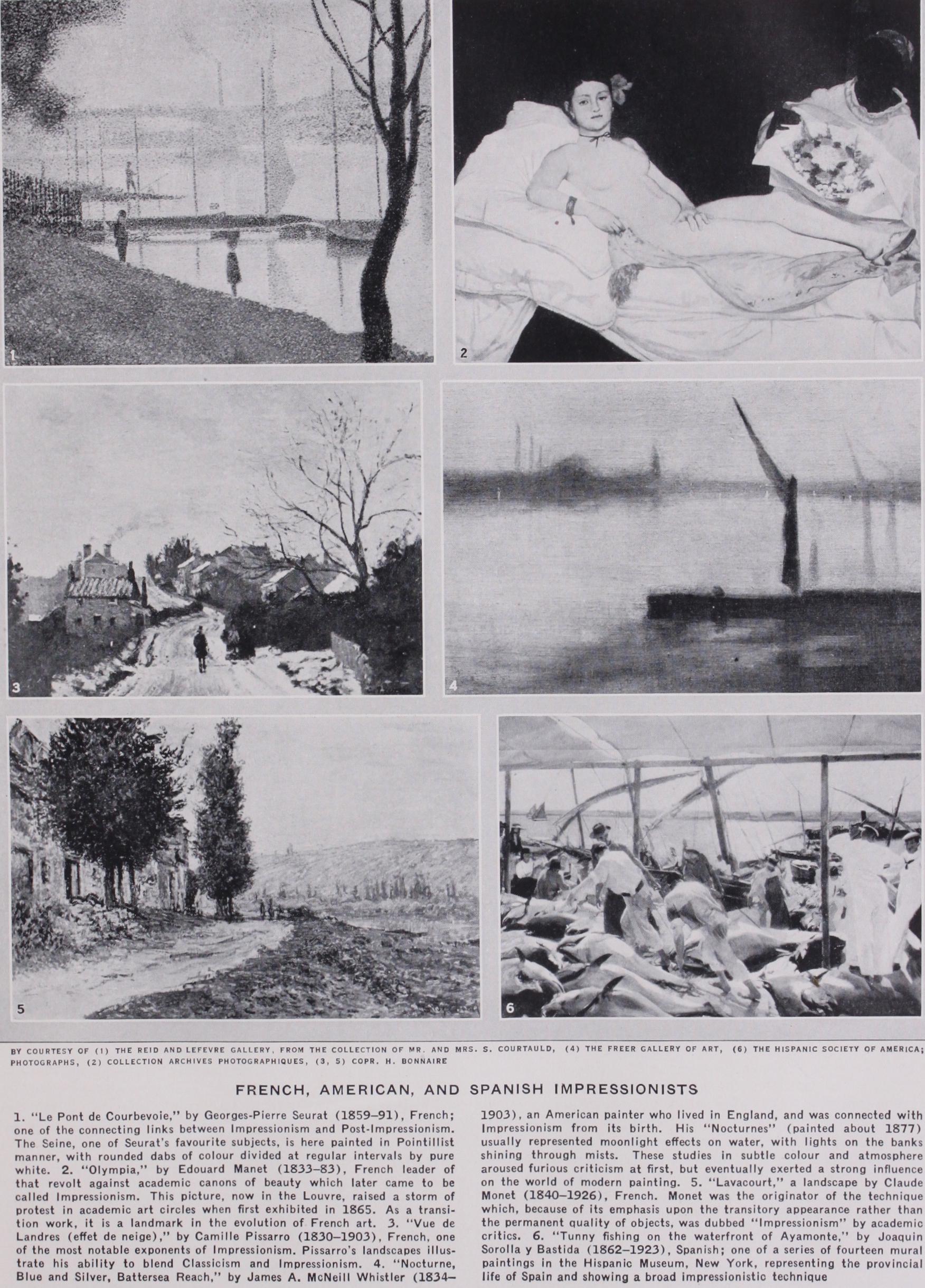

The eclectic imitators of types that have become acknowledged standards of excellence are not the upholders of tradition : their art spells decadence. The revolutionary line passes through those who, having assimilated the tradition of the past, continue to build upon it and to bring it into harmony with the age in which they live. But Manet's generation, shocked by the artist's departure from the letter, failed to recognize that he had maintained the spirit of tradition in painting an "Olympia" which was in the direct line of descent, through Velazquez's "Venus with the Mirror" and Goya's "Maja desnuda," from Giorgione's and Titian's "Reclining Venus." The picture, now in the Louvre, caused as furious a storm of indignation as the same artist's "Dejeuner sur l'herbe," which his revilers claimed to be painted in defiance of all principles of design—a charge that would scarcely have been brought against the artist, had his revilers known that the design was practically traced, line by line, from a Marcantonio engraving after a painting of "Neptune and Nymphs" by Raphael.

Degas.

Degas, although his technique had little or nothing in common with Impressionism, is generally classed with that group, because he was linked with them by the tie of friendship, took part in their exhibitions, and shared with them their keen interest in contemporary life. It was his love of actuality, of the momentary impression, that made him discard all conventional methods of composition and gave his pictures frequently an air of the accidental and unpremeditated, somewhat like a snapshot photograph. Yet behind this apparent neglect of rule lies a highly developed sense of balanced arrangement and rhythmic flow of compositional line; for Degas, too, had made a profound study of the old masters, and devoted much time to copying the primi tives. His draughtsmanship, in particular, has a classical perfection rivalled only by Ingres.

Renoir.

Renoir, who connects the art of his time with the French i8th century, adopted for a lengthy period the Impression ist technique and vision, but later in life abandoned the search after the visual truth of ephemeral effects in favour of a more permanent plasticity of form, achieved by the concentration of light on projections and of shade on recessions—a kind of model ling by means of an arbitrarily placed source of illumination for which Nature offers no parallel.

Pissaro, Sisley, Whistler and Sickert.

Less personal, though of considerable distinction, was the contribution made to the movement by Camille Pissaro and Alfred Sisley. The minor adherents to Impressionism need not here be recorded. By the close of the 19th century, Impressionism had fought through to recognition not only in France, but had gained adherence and changed the entire current of art throughout Europe. Whistler was connected with the movement from its very birth. Wilson Steer and Walter Sickert, by their example, spread the new artistic gospel in England, Leibermann and Kuehl in Germany, Segantini in Italy, Van Rysselberghe and Claus in Belgium, Sorolla in Spain, Thaulow and KrOyer in Scandinavia ; whilst among the American painters Sargent, Harrison and Alexander were profoundly in fluenced by the movement.Impressionism may be regarded as the final chapter in the gradual conquest of representational truth, which began with Giotto's vitalization of Byzantine rigidity, and proceeded step by step through the discovery of the law of perspective by the 15th century Florentines, the use of light and shade for the suggestion of relief by Leonardo da Vinci, the application of colour as an integral part of pictorial structure by the great Venetians, and the accurate registration of tone values by Velazquez. With Impressionism this search for truthful representation of appear ances had reached a point where further advance in the same direction had become impossible. Painters had succeeded in cap turing the most transient effects of surface glitter and tremulous atmosphere and, in the doing, had come dangerously near to losing their grip on form and substance.

The futility of any attempt to carry the Impressionist principles beyond the stage reached by the great initiators is demonstrated by the Neo-Impressionists, or pointillists, Sigorac and Seurat, who tried to give a scientific basis to Monet's system of divisionism by the mechanical use of rounded dabs of pure colours of equal size, divided by regular intervals of pure white. Theoretically, these dabs of spectral colours were intended to blend into luminous tones of the desired intensity when viewed from the right distance. In reality, they remained isolated dabs of colour, and the pictures thus produced bore an exasperatingly mechanical aspect.

Seurat, however, soon abandoned his rigid adherence to this method and adopted a less pronounced style of pointillism. His great importance in the history of 19th century art lies, however, in his practical protest against the disintegration of form which was the natural consequence of Monet's innovation. His later work marks a return to expressive pattern and sculptural form, and bears witness to the profundity of his outlook and to his ability to combine with his mosaic-like treatment a respect for orderly rhythm and solid volumes. Seurat thus became one of the chief connecting links between Impressionism and the modern tendencies which are embraced in the term "Post-Impressionism." (See P05T-IMPRESSIONISM, PAINTING.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.

W. Dewhurst, Impressionist Painting (Iqo4) ;Bibliography.—W. Dewhurst, Impressionist Painting (Iqo4) ; Camille Mauclair, The French Impressionists; T. Duret, Manet and the French Impressionists (191o) ; P. Signar, D'Eugene Delacroix au Neo Impressionisme (Paris, 1911) ; Max Drey, Die Malerei im XIX. Jahr hundert (Berlin, 1919) ; M. Raphael, Von Monet zu Picasso (Munich).

(P. G. K.)