Insects

INSECTS, the ordinary name used for those animals placed by zoologists in the class Insecta (or Hexapoda) of the phylum ARTHROPODA (q.v.) and whose scientific study forms that branch of zoology termed ENTOMOLOGY (q.v.). In former times the word insect had a much wider and looser significance than to-day and the class Insecta of Linnaeus (i 735) included those animals which form the whole of the Arthropoda of modern zoologists. Lin naeus's term Insecta was first used in a restricted sense by M. J. Brisson (i 756), whose application of the word has since been gen erally adopted. In 1825 P. A. Latreille applied the term Hexa poda to the insects and, since it expresses a very characteristic fea ture of those animals, it is employed by some authorities.

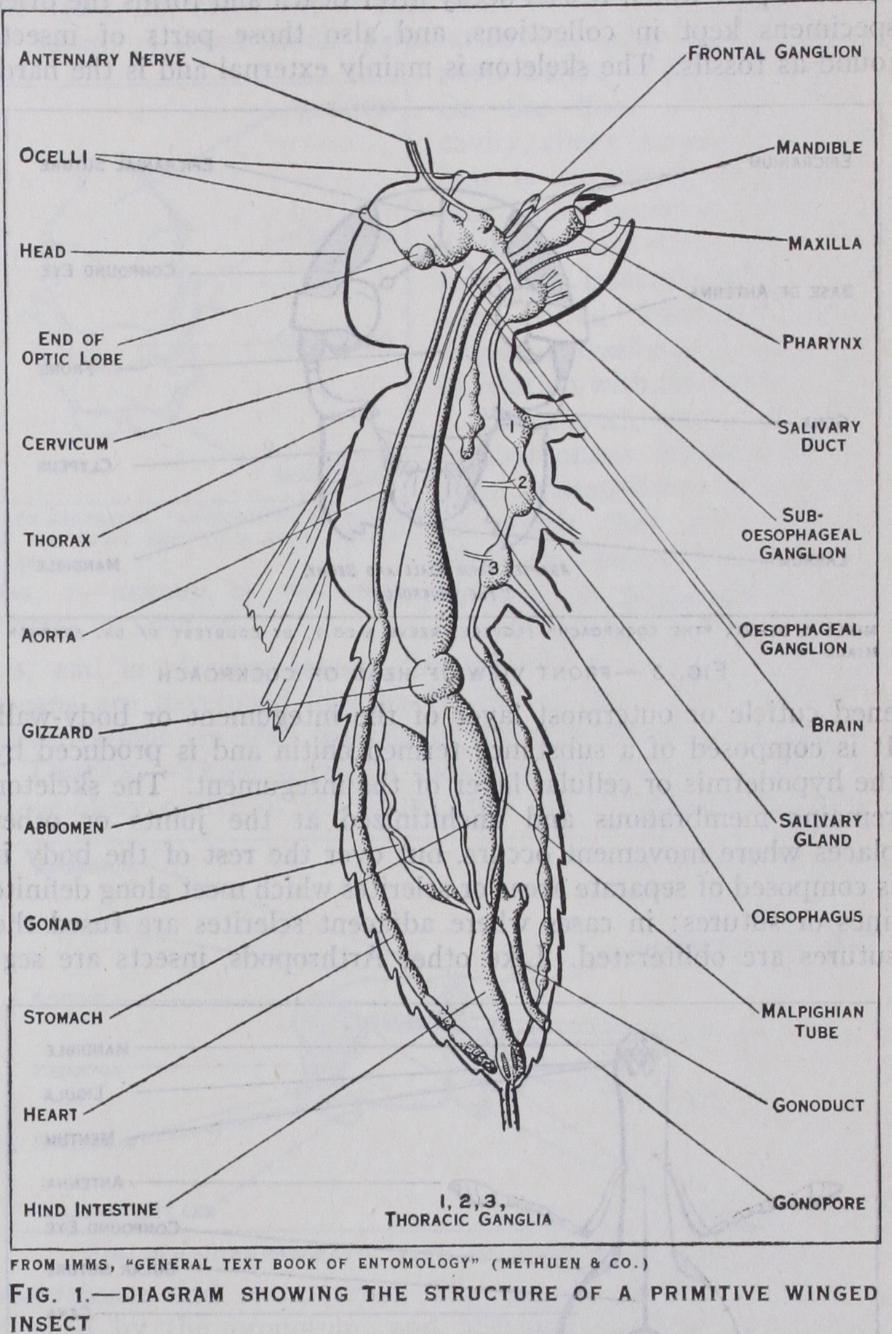

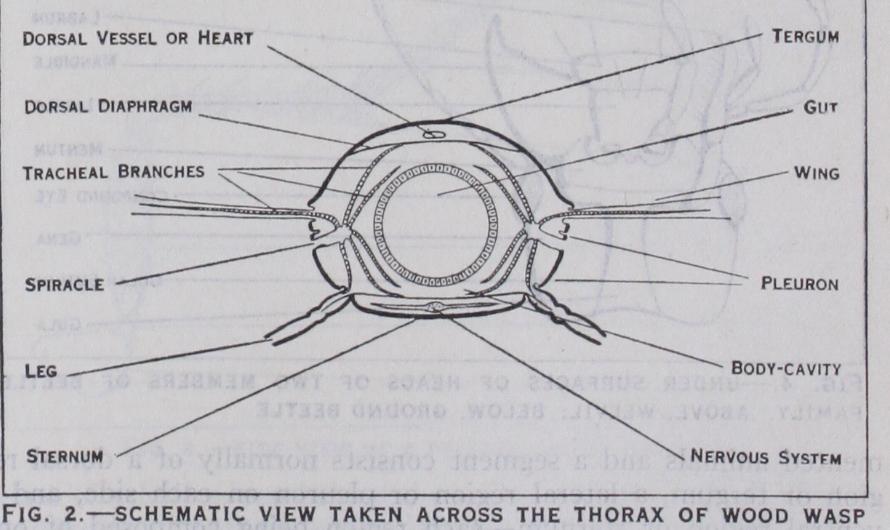

A true insect has its body divided into three distinct regions-- head, thorax and abdomen—each composed of a definite number of segments (fig. I). The head bears a single pair of feelers or antennae, a pair of mandibles and two pairs of accessory jaws or ,naxillae. The thorax carries three pairs of legs (hence the term Hexapoda) and usually two pairs, more rarely one pair, of wings. The abdomen is devoid of walking limbs and the genital opening is situated near the anal extremity of the body. Respiration takes place by means of internal air-tubes or tracheae which communi cate with the exterior by a variable number of paired openings or spiracles. After hatching from the egg the further development is rarely direct and a metamorphosis is usually undergone.

Insects probably outnumber in species all the rest of the animal kingdom, and their great numerical predominance is to be as cribed to their extraordinary adaptability to live under the most diverse conditions, and to the possession of wings. Insects repre sent the highest grade of evolution among invertebrate animals not only as regards complexity of structure, but also in psychic development as expressed in instinct. They have a world-wide range, species even occurring in the polar regions, on snow-clad mountains and glaciers, in all types of fresh water and in salt lakes; a few have invaded the sea while others have established themselves in hot springs, in deep wells and in caves where light never penetrates. It is, however, in the Tropics that insect life exhibits its greatest wealth of species and diversity of form and coloration.

In point of size insects present a wide range of differences: as J. W. Folsom has well expressed it, some insects are smaller than the largest Protozoa and others are larger than the smallest Verte brata. If size be gauged by bulk combined with body-length, the beetle Macrodontia cervicornis, which ranges up to i 5omm. (6in.) long, is to be regarded as one of the giants, while a length of 33cm. (r 3in.) is reached by some of the greatly attenuated stick-insects (q.v.). In wing expanse alone the moth Erebus agrippina with a spread of 28omm. (i 'in.) is unsurpassed among living insects al though certain fossil dragon-flies measure over 2 f t. from wing to wing. At the other end of the scale there are beetles which do not exceed a length of -4mm. and some minute wasp-like parasites are even smaller.

Apart from the interest that the structure habits and transf or mations of insects afford to the nature student the whole class is of very great importance in its relations to man. Many species are a direct menace to his food supply, some attack raw materials and others act as vectors of the pathogenic agents of disease both in man and in domestic animals. (See ENTOMOLOGY : Economic and Medical.)