Internal Anatomy

INTERNAL ANATOMY The internal organs of an in sect, like those of other Arthro pods, lie in a common body-cavity or haemocoele which contains blood and is in free communica tion with and forms part of the general circulatory system.

Nervous System and Sense Organs.—The central nervous system consists typically of a ventral nerve cord with a pair of nerve centres or ganglia in each segment of the body : it is joined by a connective on either side of the gullet with the brain (fig. 14). The brain lies in the head just above the gullet and consists of three fused ganglia which in nervate the antennae and visual organs. The first ganglion of the ventral cord is the suboesoph ageal ganglion which lies. in the head just below the gullet and innervates the mouth-parts. The next three ganglia are situated one in each of the thoracic segments and innervate the wings and legs, while the remaining ganglia of the ventral cord belong to the abdomen. In the more specialized insects a variable number of the ganglia undergo fusion and as in the housefly, all the thoracic and abdominal ganglia are merged into a common centre.

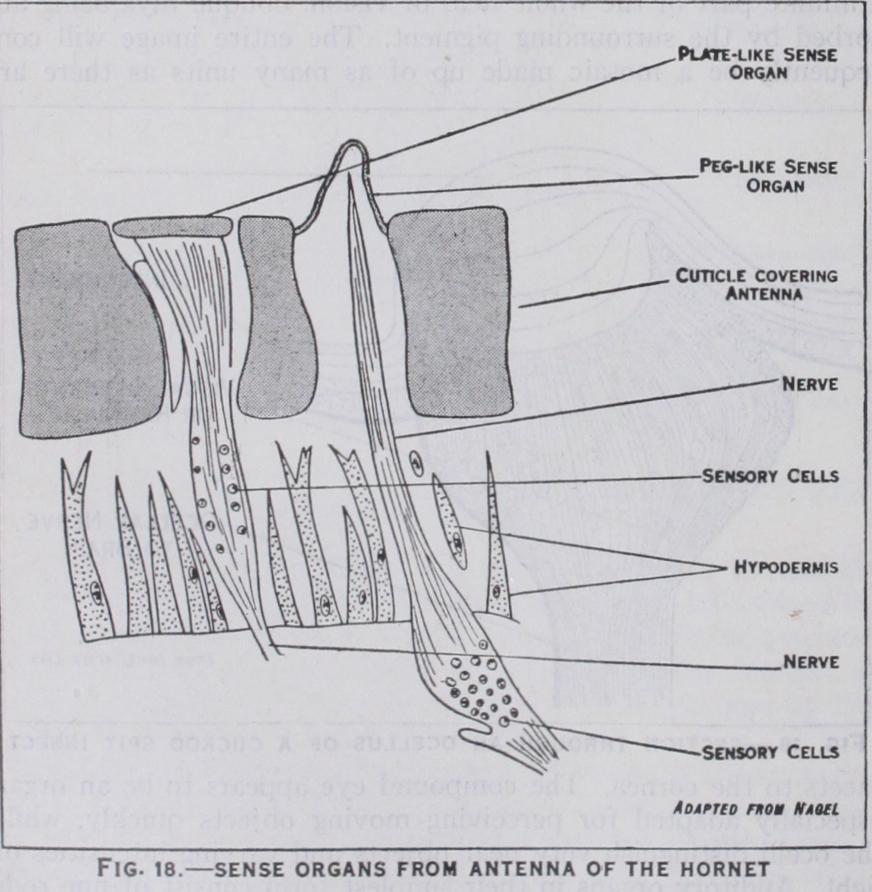

Connected with the nervous system are the organs of special sense. Visual organs consist of compound eyes and ocelli: typ vided cornea is replaced by a single biconvex lens which over lies the visual elements (fig. i6). Vision by means of compound eyes is explained by the mosaic theory which maintains that only those rays of light entering a facet which are parallel with the long axes of the ommatidia, reach the retina where they register a minute part of the whole field of vision, oblique rays being ab sorbed by the surrounding pigment. The entire image will con sequently be a mosaic made up of as many units as there are facets to the cornea. The compound eye appears to be an organ especially adapted for perceiving moving objects quickly, while the ocelli distinguish very near objects and varying intensities of light. Auditory organs in their simplest form consist of fine rods suspended between two points of the integument and connected with nerve-fibres : in such a condition they are present in many insects and larvae. In other cases more elaborate organs are de veloped, and in grasshoppers (Acridiidae) there is a tympanic membrane on either side of the first abdominal segment which is in contact with a delicate sac containing fluid and receiving nerve-endings (fig. 17). In long-horned grasshoppers and crickets a small swelling below the knee joint bears two narrow slits which lead into chambers whose delicate walls are in contact with air tubes and bear nerve-endings. In both these examples sound waves impinge on an auditory membrane whose vibrations are transmitted by nerve fibres to the central nervous system. Sense perception of other kinds takes place by means of modified hairs covered by a very delicate cuticle and in direct connection with a nerve fibre. Included in this category are tactile organs which closely resemble ordinary hairs and are widely distributed over the body and appendages: olfactory organs (fig. 18) which are more variable and modified in form and are present in large numbers on the antennae, especially of male insects: and gusta tory organs whose taste function is presumed from their loca tion on parts near or connected with the mouth-cavity.

Muscular System

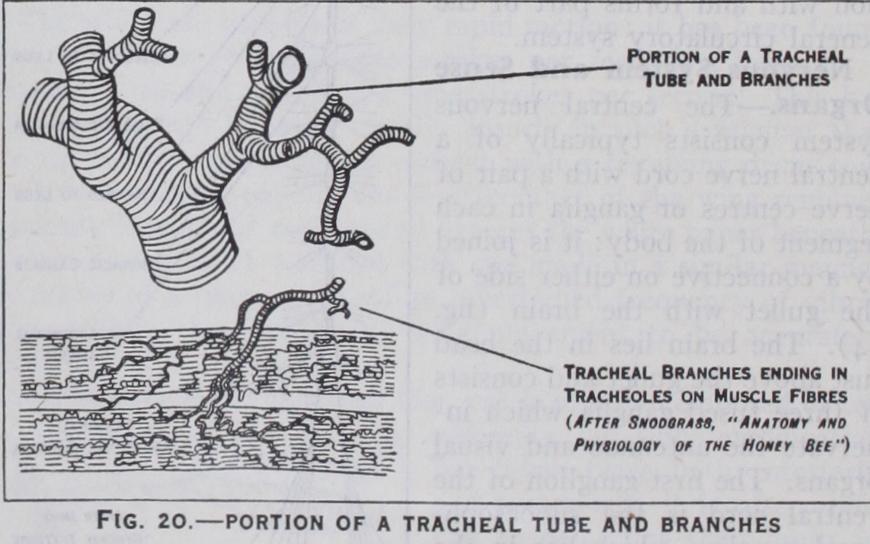

(fig. i o) .—Unlike those of vertebrates the voluntary and involuntary muscles of insects are cross-striated. In the thorax and abdomen the muscles are arranged in (i ) a longitudinal series, both tergal and sternal muscles being present, (2) a dorso-ventral series and (3) a pleural series. In the thorax there are also other special muscles connected with the move ments of the legs and wings. The head contains numerous mus cles which comprise the abductor and adductor muscles of the mouth-parts and cervical mus cles controlling the movements of the head.Respiratory System.—T h e respiratory organs consist of a much branched system of air tubes or tracheae (fig. which are kept distended by spirally arranged thickenings of their chitinous lining (fig. 2o). The small tracheae end in fine capil laries or tracheoles which pass to the various organs of the body. Air enters the tracheae through paired lateral openings or spir acles: each spiracle is surrounded by a chitinous rim and is generally provided with a clos ing apparatus and often special devices to exclude foreign mat ter. The typical number of spir acles is ten pairs—two pairs on the thorax and eight pairs on the abdomen, but this number is often reduced, especially in larvae.

Respiratory movements on the part of the insect facilitate the entry of air into the tracheae whence it passes by diffusion into the tracheoles, where it finally gives up its oxygen to the tissues. Carbon dioxide is got rid of partly by diffusion through mem branous areas of the integument and partly by passage through the tracheae, it being finally expelled through the spiracles by the contraction of the tergosternal muscles which compress the body. Many aquatic insects breathe by means of tracheal gills. In other insects, which have no tracheae, respiration is cutaneous.

Circulatory System.

The heart in an insect is represented by a tubular contractile dorsal vessel which is composed of suc cessive chambers and runs along the middle line of the back, just below the integument (fig. i ). It lies in the pericardial sinus whose floor is formed by the pericardial diaphragm, and there is usually a ventral diaphragm, enclosing a peri-neural sinus surrounding the nerve cord (fig. 8). The dorsal vessel pumps the blood forward, through its anterior prolongation or aorta, into the body-cavity : here it bathes the various organs and flows through the appendages. The pulsations of the two diaphragms keep the blood in circulation and it is eventually returned to the pericardial sinus through openings in the diaphragm. Here it makes its way back to the dorsal vessel, entering the latter organ through paired valvular inlets placed at the constrictions between adjacent chambers. The blood is composed of a fluid or plasma containing amoeba-like corpuscles, somewhat resembling the leucocytes of mammalian blood. Although it plays a part in res piration, its chief function is the circulation of nutrient material among the various organs of the body.

Digestive System.

The digestive canal (fig. 22) is divided into fore-gut, mid-gut or stomach and hind-gut : the first and third regions are formed as tubu lar inpushings of the integument and are lined with thin cuticle, while the mid-gut is developed as a separate chamber. The f ore gut consists of a narrow gullet, a sac-like crop and often a gizzard: in Lepidoptera and many flies the crop is a separate food-reser voir connected by a canal with the gullet (fig. 23) . On either side of the fore-gut are the salivary glands which open into the mouth-cavity. The mid-gut is short, and often provided with outgrowths or caeca, while the hind-gut consists of a tubular in testine and an end-chamber or rectum. Arising from the hind gut, near its junction with the mid gut is a variable number of slen der Malpighian tubes. The food during mastication is mixed with saliva whose enzymes act upon the starchy matter. The secre tions of the mid-gut deal chiefly with proteids and fats and resem ble those of the pancreas of verte brates. Digestion often takes place largely in the crop while the mid-gut is the seat of absorption and the hind-gut conducts waste products to the exterior.Excretory S y s t e m.—The Malpighian tubes function as kid neys and eliminate urates and other waste products from the blood, discharging them into the hind intestine (figs. 22 and 23).

In many insects the fat-body, or irregular tissue found in the body-cavity, also functions in an excretory capacity, but it mainly stores up nutrient reserves to be drawn upon during metamor phosis.

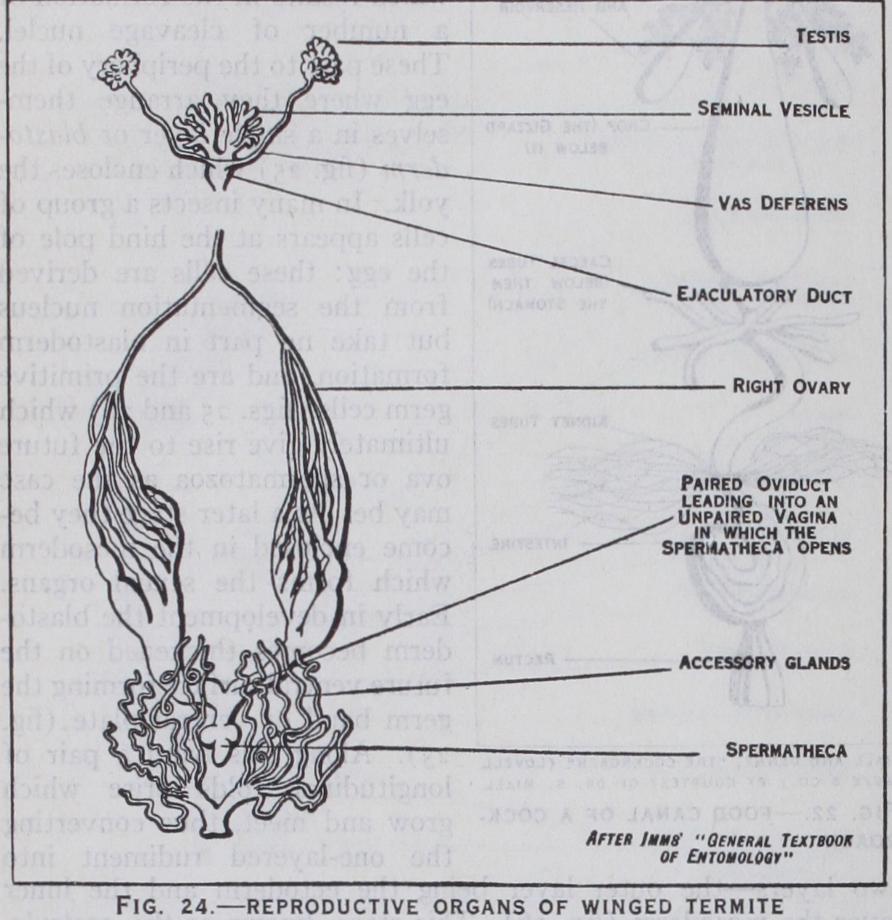

Reproductive System.--In

the female (fig. 24) the ovaries are paired organs each formed of a variable number of egg-tubes or ovarioles which contain the developing ova. The latter as they ripen pass down the oviducts to enter a median passage or vagina and are discharged through the female genital pore which is usu ally placed between the sterna of the eighth and ninth abdominal segments. There are also generally a spermatheca for storing the sperms and paired accessory glands. In the male (fig. 24) the testes are likewise paired and are formed of seminal tubes which produce the sperms. The sperms are discharged into paired ducts or vasa de f erentia, and finally into a median ejaculatory duct open ing in the aedeagus or intromittent organ, which is placed between the ninth and tenth abdominal sterna. Sometimes the vasa defer entia are locally enlarged as seminal vesicles for storing the sperms and accessory glands may also be present. Fertilization of the ova depends upon the union of the sexes, which, in some insects, may occur several times in the life of the individual, either male or female.

The Egg.

The eggs are usually rich in yolk for nourishing the growing embryos : many eggs are elongate-oval in shape, others are spherical, and some are flattened or flask-shaped : the outer coat (cliorion) is often elaborately sculptured. Eggs may be laid singly or in groups : enclosed in capsules or oothecae, as in cock roaches, etc., or enveloped in a gelatinous mucilage as in some midges and caddis flies, which lay them in water.

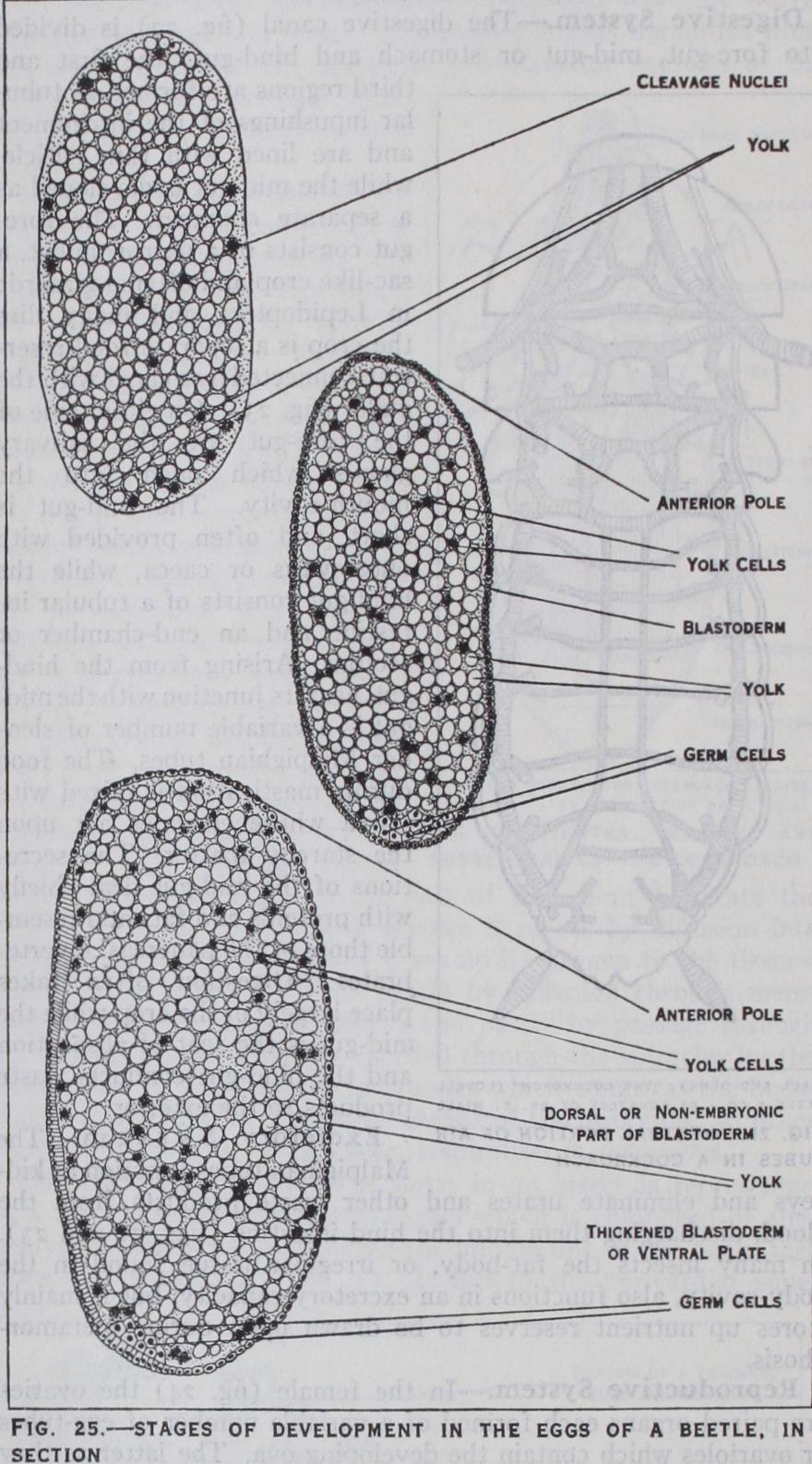

Early

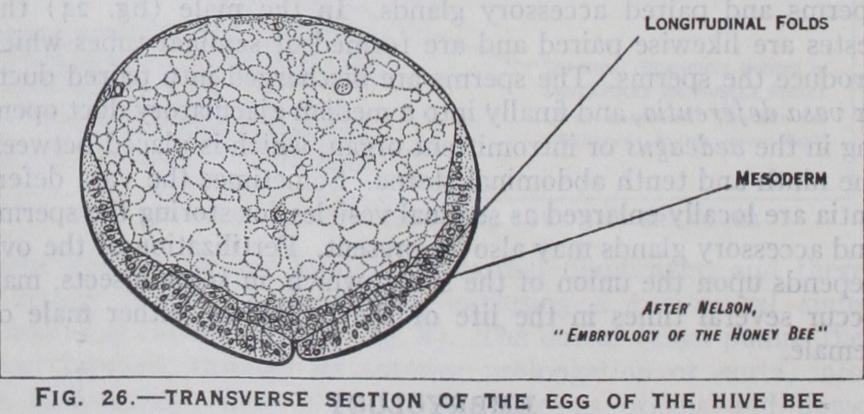

maturition and fertilization of the egg have taken place, devel opment commences by the divi sion of the segmentation nucleus which results in the formation of a number of cleavage nuclei. These pass to the periphery of the egg where they arrange them selves_ in a single layer or blasto derm (fig. 25) which encloses the yolk. In many insects a group of cells appears at the hind pole of the egg : these cells are derived from the segmentation nucleus but take no part in blastoderm formation, and are the primitive germ cells (figs. 25 and 26) which ultimately give rise to the future ova or spermatozoa as the case may be. At a later stage they be come enclosed in the mesoderm which forms the sexual organs. Early in development the blasto derm becomes thickened on the future ventral surface forming the germ band or ventral plate (fig. 25). Along this band a pair of longitudinal folds arise which grow and meet, thus converting the one-layered rudiment into two layers—the outer layer being the ectoderm and the inner layer the mesoderm (fig. 26). This stage, known as the gastrula, which is an important phase in the development of all animals, is subject to several variations in insects.

Formation of the Embryo

(fig. 2 7) .—Early on, the germ band becomes divided by transverse furrows into a series of seg ments of which six form the future head, three form the thorax and i i or i 2 form the abdomen : at this stage the germ band may be referred to as the embryo. On each segment, except the first and last, pairs of bud-like appendages appear. These, in all insects, form the future antennae, mouth-parts and legs, while the remain der, with certain exceptions, usually disappear before the embryo is fully developed. The transient appendages are the small second pair, behind the antennae, and those borne on the abdomen. Among Apterygota certain of the abdominal appendages form those of the adult and in caterpillars they develop into abdominal feet. In other insects cerci, when present, are formed from the last pair, but the rest of the abdominal appendages disappear. The gonapophyses are believed to be derived from abdominal append ages of the eighth and ninth segments, but direct proof is wanting. Along either side of the middle line of the ectoderm a pair of ridges develop which are the fundaments of the nervous system. They become segmented into paired swellings or neuromeres, one neuromere lying in each embryonic segment. The first three neuromeres give rise to the brain, the next three form the sub oesophageal ganglion and the remainder form the ganglia of the thorax and abdomen. At a later stage pits appear on the outer side of the last two thoracic and the first eight or nine abdominal appendages, these being the rudiments of the spiracles.

Embryonic Membranes

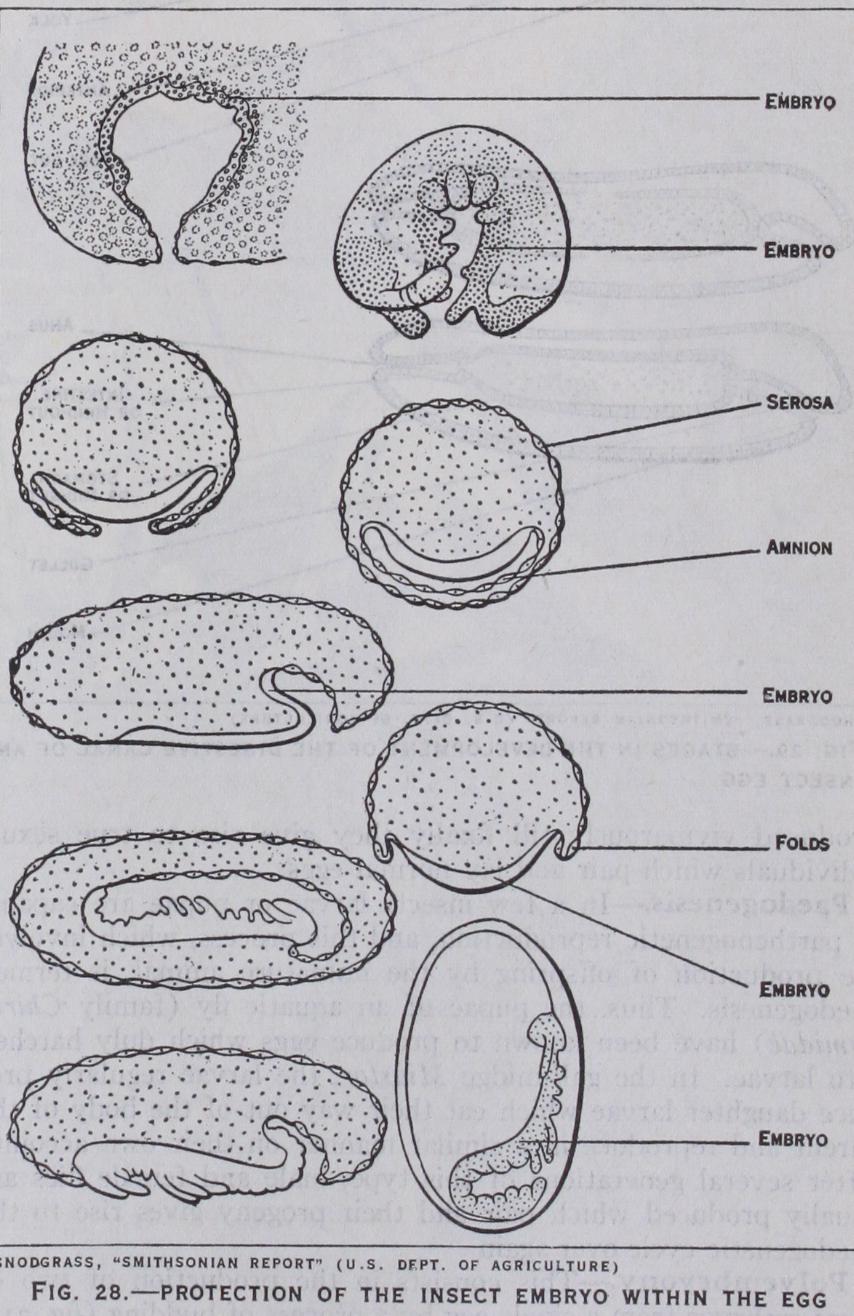

(fig. 28).—In some insects such as beetles the embryo remains at the surface of the yolk, but it sub sequently becomes covered by f olds which arise along its edges. These folds grow towards one another and fuse, and in this way enclose the embryo in an amniotic cavity which is covered by an outer membrane or serosa and an inner membrane or amnion (fig. 28). In some other insects such as butterflies and dragon flies the embryo becomes sunk into the yolk and a portion of the non-embryonic part of the blastoderm becomes necessarily carried in with it, forming the amnion. In a moth or butterfly the embryo sinks into the yolk without change of orientation, but in dragon flies it moves through an arc until its position is completely re versed on the dorsal side of the yolk. Here it rests for a while and again passes through the same arc to its original ventral position.

Digestive System

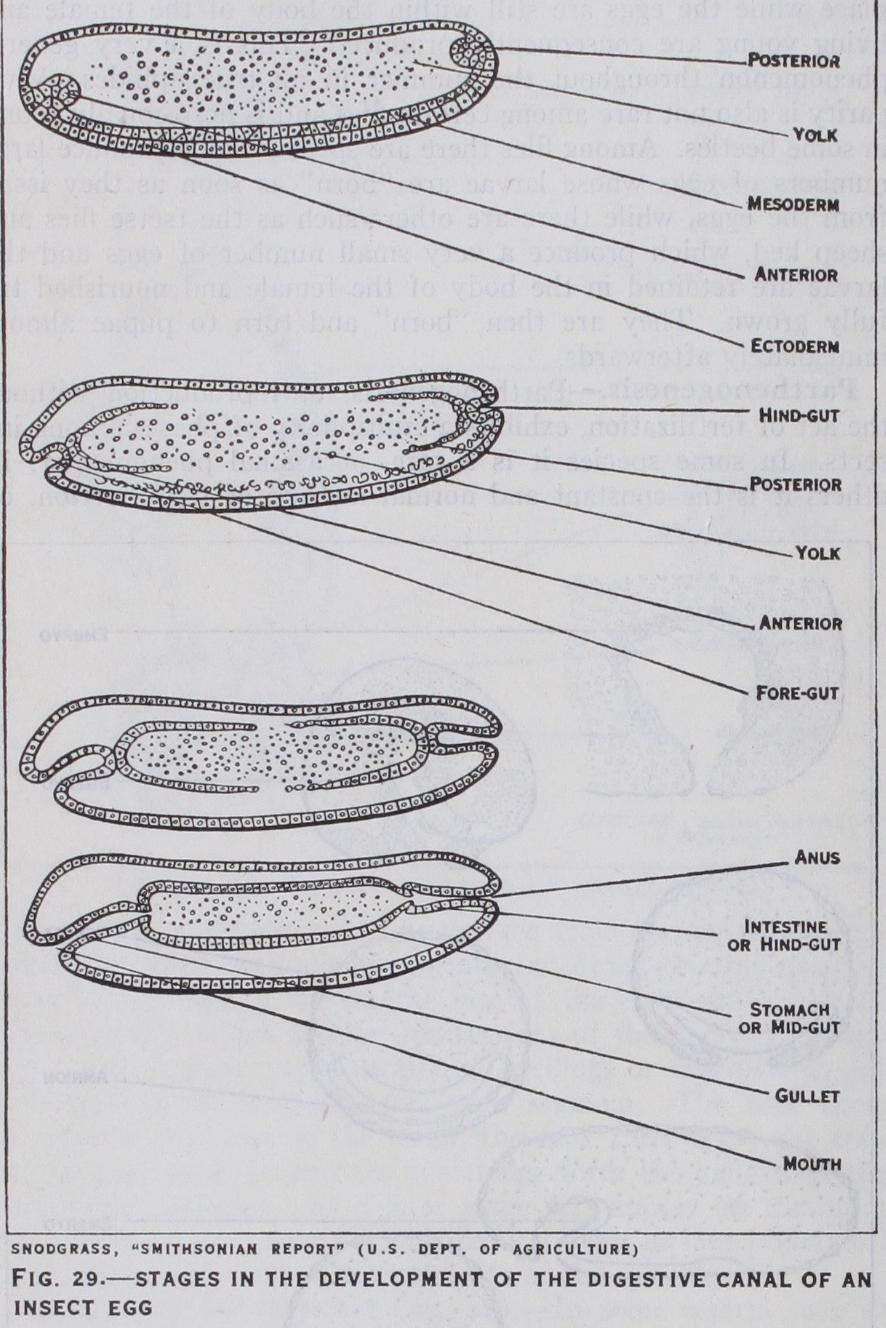

(fig. 29).—In the positions of the future mouth and anus the ectoderm becomes inpushed to form the rudiments of the fore-gut and hind-gut respectively. The method of origin of the mid-gut is much disputed: by some embryologists it is believed to arise partly from the mesoderm and partly from cells budded off from the previously mentioned gut-rudiments others claim its origin from the latter source only. The Malpighian tubes develop as outgrowths from the hind-gut when the latter is little more than a pit, and subsequently become carried inwards as the gut-rudiment deepens.

Dorsal Closure

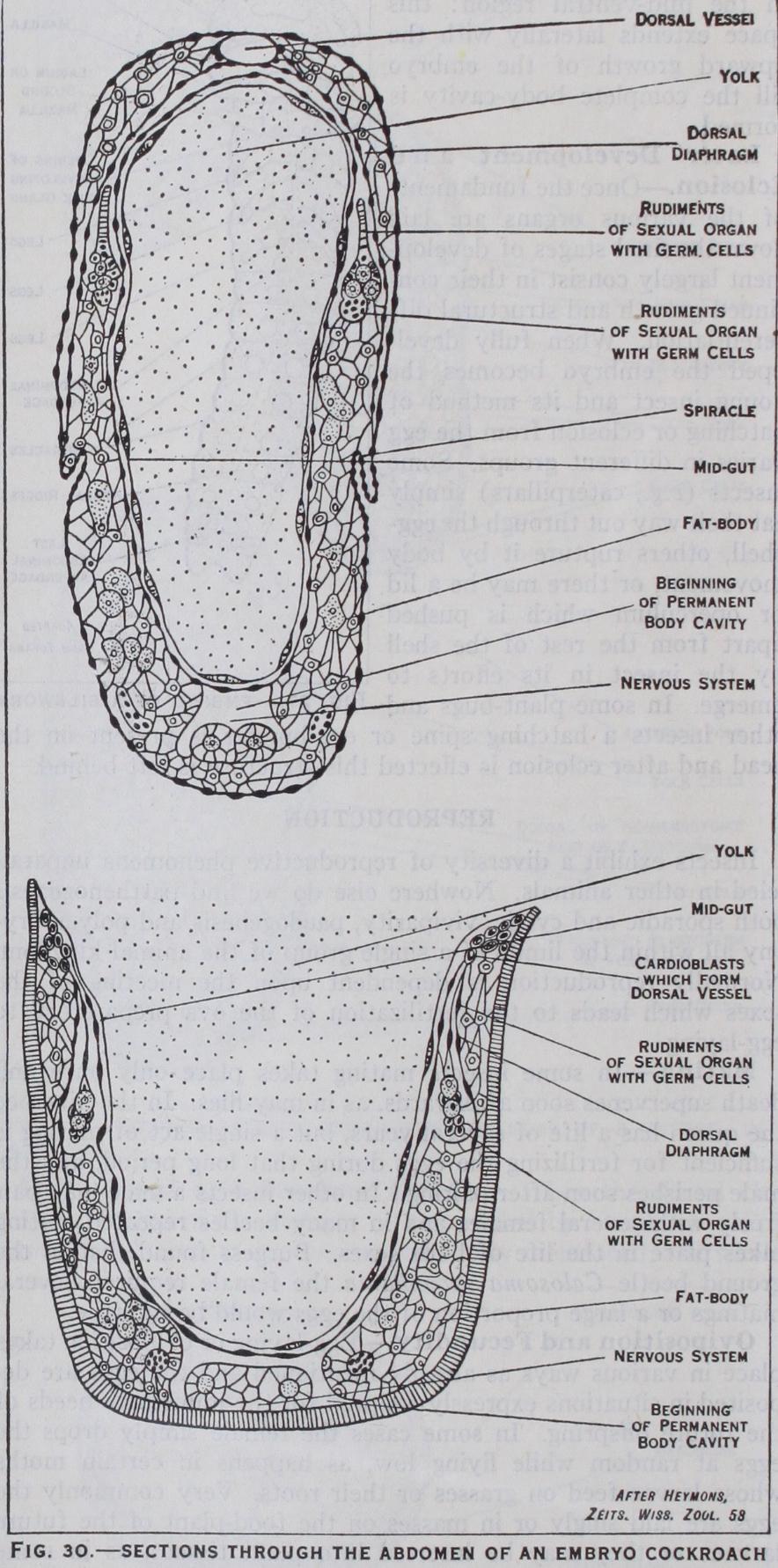

(fig. 30).—As development proceeds the em bryo broadens out and gradually grows around the yolk until its sides finally meet and fuse along the dorsal region. In many in sects either the amnion or serosa ruptures over the region of the embryo to allow of its growth, but in Lepidoptera these mem branes remain intact, and the amniotic cavity follows the growth of the embryo around the yolk.

Integument and Tracheal System.

When the dorsal clo sure is completed the embryo is surrounded by ectoderm which forms, in addition to the organs previously mentioned, the whole integument of the body and its appendages together with the tracheal system and salivary glands. The tracheae arise from the original spiracular pits which deepen into tubes and become freely branched as development proceeds.

Mesoderm and Organs Derived from It

(fig. 3o).—The mesoderm or inner layer of the germ band undergoes segmenta tion corresponding with that of the ectoderm. Coelomic cavities appear in these mesoderm segments, but they subsequently break down and take little part in the formation of the permanent body cavity as happens in so many animals. The mesoderm gives rise to the dorsal vessel, fat-body, muscles and the sexual organs and their paired ducts, but the vagina and the ejaculatory duct respec tively are derived as inpushings of the ectoderm. The body-cavity is chiefly formed from a space that is produced by the separation of the yolk from the mesoderm in the mid-ventral region : this space extends laterally with the upward growth of the embryo till the complete body-cavity is formed.Later Development a n d Eclosion.—Once the fundaments of the various organs are laid down the final stages of develop ment largely consist in their con tinued growth and structural dif ferentiation. When fully devel oped the embryo becomes the young insect and its method of hatching or eclosion from the egg varies in different groups. Some insects (e.g., caterpillars) simply eat their way out through the egg shell, others rupture it by body movement, or there may be a lid or operculum which is pushed apart from the rest of the shell by the insect in its efforts to emerge. In some plant-bugs and other insects a hatching spine or egg-burster is present on the head and after eclosion is effected this structure is left behind.

Insects exhibit a diversity of reproductive phenomena unparal leled in other animals. Nowhere else do we find parthenogenesis both sporadic and cyclic, viviparity, paedogenesis and polyembry ony all within the limits of a single group of the animal kingdom. Normally reproduction is dependent upon the meeting of the sexes which leads to the fertilization of the ova preparatory to egg-laying.

Mating.

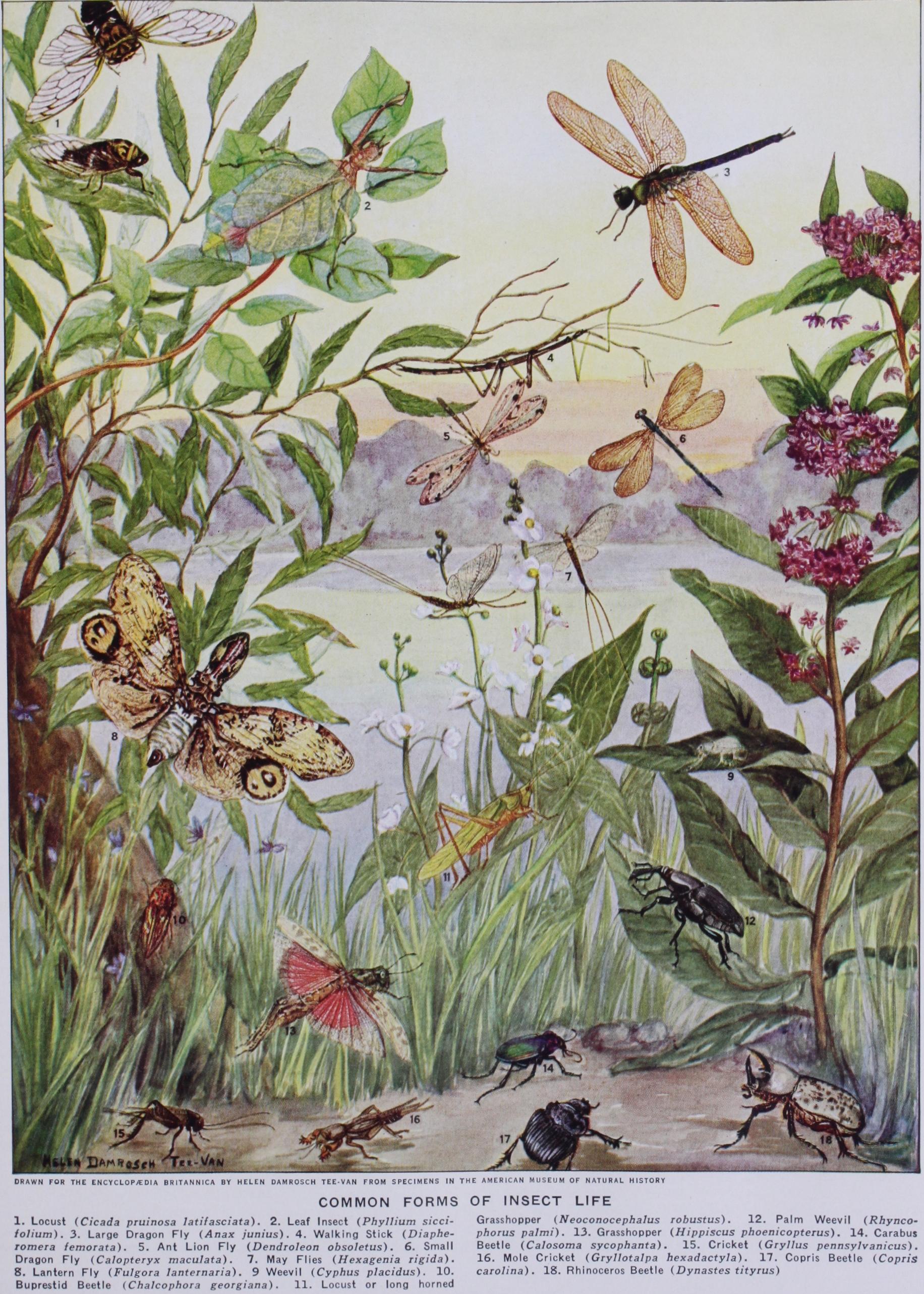

In some insects mating takes place only once and death supervenes soon afterwards, as in may-flies. In the hive bee the queen has a life of several years, but a single act of mating is sufficient for fertilizing the eggs during that long period, and the male perishes soon after pairing. In other insects a male may pair freely with several females and in many beetles repeated mating takes place in the life of both sexes. Burgess found that in the ground beetle Calosoma sycophanta the female required several matings or a large proportion of the eggs would be infertile.

Oviposition and Fecundity.

Egg-laying or oviposition takes place in various ways as already mentioned and the eggs are de posited in situations expressly adapted for the immediate needs of the future offspring. In some cases the female simply drops the eggs at random while flying low, as happens in certain moths whose larvae feed on grasses or their roots. Very commonly the eggs are laid singly or in masses on the food-plant of the future larvae : or they may be inserted into plant tissues, as in some grasshoppers. When inserted more deeply excrescences or galls may arise as in saw-flies, gall-wasps and gall-midges. Other insects lay their eggs beneath the soil, while parasitic species lay them on or within the bodies of the hosts which support their future off spring.The number of eggs laid by the female greatly varies among different species. In the Phylloxera of the vine and the woolly aphis, the winter females lay but a single large egg apiece; the mussel scale in England lays on an average less than 4o eggs ; the moth Hadena oleracea lays over Soo eggs, and the house-fly may deposit over 2,000 eggs during its life. The maximum fecundity is reached among termites whose queens are often little more than huge inert egg-laying machines producing upwards of 4,00o eggs every 24 hours, and i,000,000 eggs a year during a life of per haps six to nine years.

Viviparity.

In some insects embryonic development takes place while the eggs are still within the body of the female and living young are consequently produced. This is a very general phenomenon throughout the summer in all true aphides. Vivi parity is also not rare among certain flies and is occasionally found in some beetles. Among flies there are species which produce large numbers of eggs whose larvae are "born" as soon as they issue from the eggs, while there are others such as the tsetse flies and sheep ked, which produce a very small number of eggs and the larvae are retained in the body of the female and nourished till fully grown. They are then "born" and turn to pupae almost immediately afterwards.

Parthenogenesis.

Parthenogenesis, or reproduction without the act of fertilization, exhibits a multiplicity of phases among in sects. In some species it is a rare, occasional phenomenon : in others it is the constant and normal method of reproduction, or it may be cyclic—alternating with sexual reproduction. Partheno genesis may, therefore, be classed under three headings : ( ) Spo radic, which happens especially among moths and is more frequent in some species than in others : both males and females may be produced from the unfertilized eggs ; (2) Constant : in social bees and wasps the males are regularly produced from the unfertilized eggs, and the same happens in many of the Chalcids. In some of the stick-insects females only are produced and the males are very rare : again, in certain gall-wasps and saw-flies males are unknown and sexual reproduction is consequently absent. (3) Cyclic: in many gall-wasps and almost all aphides one or more partheno genetic generations alternate with a sexual generation. In the gall wasps the individuals of the two generations are often very dif ferent in form and produce dissimilar galls. The spring genera tion consists of females which give rise to a summer generation of both sexes which mate and produce the spring females of the next year. In aphides generation after generation of virgin females are produced viviparously till finally they give rise to true sexual individuals which pair and lay normal eggs.

Paedogenesis.

In a few insects larvae or pupae are capable of parthenogenetic reproduction, and this process, which involves the production of offspring by the immature animal, is termed paedogenesis. Thus, the pupae of an aquatic fly (family Chiro nomidae) have been known to produce eggs which duly hatched into larvae. In the gall-midge Miastor, the larvae regularly pro duce daughter larvae which eat their way out of the body of the parent and reproduce in a similar manner on their own account. After several generations of this type, male and female flies are usually produced which pair and their progeny gives rise to the paedogenetic cycle over again.

Polyembryony.

This consists in the production of two or more embryos from a single egg by a process of budding (fig. 3 I) . It is only found in certain of those Hymenoptera whose larvae live as parasites in the blood and tissues of other insects. The sim plest case is found in a minute creature Platygaster hiemalis which is a parasite of the Hessian fly. Some of the eggs of this parasite develop normally into larvae, while others develop up to a point when the embryo divides so as to produce two larvae within the same egg-covering. In other species ten or i 2 larvae may arise from a single egg, while in some chalcid wasps which parasitize caterpillars, i oo or more larvae may be produced from a single embryo. These develop in a continuous chain enveloped in a cel lular covering and, when mature, they separate and become free in the body of their host. The resultant insects may be female or male, according to whether the original egg was fertilized or not. As many as 3,000 larvae are known to issue from a single cater pillar of the Silver Y moth in which several of these chains of embryos were present.After hatching or birth, insects undergo a process of growth and change till they become adult. Every insect during its growth sheds its cuticle several times, this process being known as moult ing or ecdysis, the cast skin' being the exuvia. The form assumed by an insect between successive moults is termed an instar: thus, when it issues from the egg it is in its first instar and after the sec ond ecdysis it is in its third instar, and so on. The final instar is the fully mature insect or imago.

Metamorphosis.

Most insects issue from the egg in a differ ent form from that assumed in the imago and in order to reach the latter condition, they have to pass through changes that are collec tively termed metamorphosis. A small number of insects emerge from the egg in their completed form and therefore do not undergo metamorphosis. Such insects are often termed Ametabola, spring tails and bristle-tails being familiar examples. Certain other in sects, which have lost their wings in their remote ancestry, have their transformations so reduced that they no longer merit the term metamorphosis. Such examples are consequently secondarily ametabolous and they exhibit only trivial differences between the young and adults : examples of this kind are found among stick insects, lice, worker termites and other insects. The majority of insects, however, pass through a metamorphosis and may be termed Metabola. In the strict zoological sense the young of all animals undergoing metamor phosis are called larvae. Among insects it is convenient and cus tomary to distinguish two types of immature individuals, viz., nymphs and larvae.

A nymph (fig. 32) is an imma ture insect which quits the egg in a relatively advanced stage and mainly differs from the imago in that the wings and gonapophyses, when present, are in a relatively rudimentary c o n d i t i o n. The mouth-parts resemble those of the adult and compound eyes are present. Growth from the nymph to the imago is gradual and un accompanied by a pupal instar.

A larva (figs. 36 and 37) is an immature insect which leaves the egg in a form very different from that of the imago. It is struc turally less advanced than a nymph, it never bears external rudiments of wings, and compound eyes are wanting.

Types of Metamorphosis.

From the foregoing remarks it will be noted that metamorphosis is of two types. In cases where the young insects are nymphs and there is no pupa, the change to the imago is direct and gradual, and metamorphosis is said to be incomplete (fig. 35). When the young insects are larvae which ultimately transform into pupae, metamorphosis is of an indirect and complex character and is said to be complete (fig. 33).

Types of Larvae.

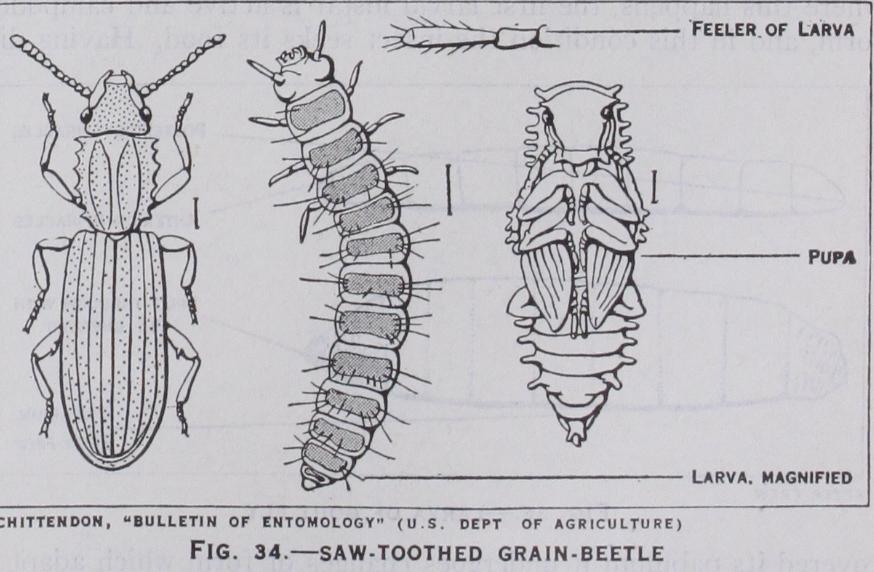

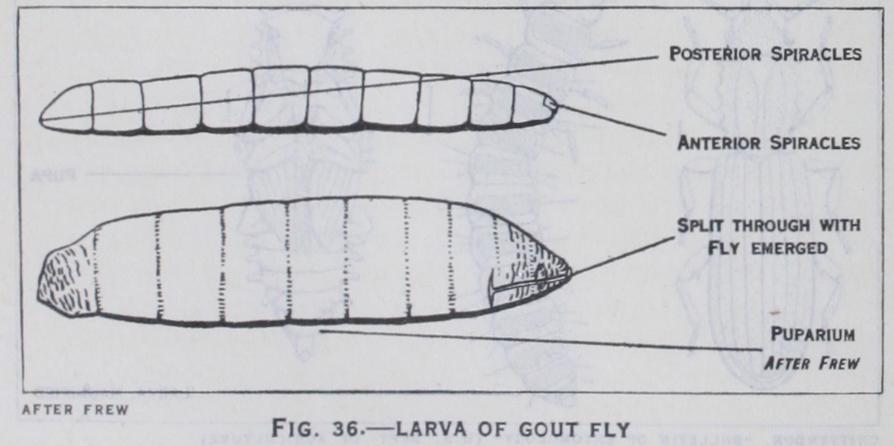

Larvae issue from the egg in different stages of development which partly depend upon the amount of yolk that was available for their growth : generally, the less yolk there is the more immature are the larvae when they hatch. Larvae may be grouped under four types : (I) Embryonic larvae: these occur among some of the parasitic Hymenoptera whose eggs con tain little or no yolk. They are so immature that they are little more than prematurely hatched embryos with an unsegmented abdomen and no appendages be hind those of the thorax: the digestive and nervous systems are as yet rudimentary and the tracheal system is undeveloped. Such larvae live as parasites in the blood or other tissues of various insects and are thus sur rounded by a highly nutritious food ; (2) Eruci f orm larvae: these emerge from the egg at a much later stage when segmenta tion is complete and the internal organs are fully formed. Their special feature is the retention of a variable number of the embry onic abdominal appendages which are transformed into feet (fig.33). Such larvae are known as caterpillars and are found in saw flies, butterflies and moths; (3) Campodeiform larvae (fig. 34) larvae which bear this name are hatched in a form bearing a gen eral resemblance to Campodea and other bristle-tails. They are carnivorous creatures that wander in search of their prey : the in tegument is well chitinized and the antennae, legs and cerci are prominently developed. In conformity with their active life, eyes and other sense organs are evident. Larvae of this type hatch late from the egg after the loss of the embryonic abdominal append ages. In many respects they resemble the nymphs of insects with incomplete metamorphosis, but are less advanced in their develop ment. Campodeiform larvae are characteristic of ground beetles and Neuroptera; (4) Vermiform larvae (fig. 36) : these are very varied in form and are worm-like or maggot-like with only vestiges of legs and antennae, or entirely legless. They are believed to be derived from the campodeiform type by degeneration induced by the presence of abundant food supply, which renders locomotory and sense organs of little value to the insect. Vermiform larvae occur in all flies, some beetles and in most Hymenoptera.

In addition to the foregoing there are many larvae that are of an intermediate character. Such larvae in general facies are cam podeif orm but in other characters incline towards the eruciform or, more usually, the vermiform type.

Ecdysis.—Since the cuticle is ill-adapted to accommodate itself to the increase in size of an insect consequent upon growth it is periodically shed. During each act of ecdysis not only the general cuticle covering the body and appendages is cast off, but also the cuticular lining of the tracheae, fore-gut and hind-gut. All these parts together with hairs, spines and similar structures are re newed by the activity of the hypodermal cells beneath them. Be fore moulting actually takes place special glands secrete a fluid which penetrates between the old and new layers of cuticle and facilitates the final separation and rupture of the old skin. Spring tails are the only insects that regularly undergo ecdysis after be coming adult, while may-flies undergo a moult on attaining the winged state, but before they are fully mature. In all other in sects moulting is confined to the larvae and nymphs. Among the larvae of many flies and Neuroptera two-ecdyses are very constant : in caterpillars moulting is variable, some may have nine ecdyses while in others it may be as low as three. In the may-fly Chloeon 23 ecdyses have been observed.

Growth.—The larval and nymphal periods are pre-eminently ones of growth and the increase in weight that is undergone in a short interval of time is remarkable. Among the influences that affect growth most profoundly are nutrition and temperature. In sufficient food, or food of the wrong nutrient composition, retards growth and consequently delays metamorphosis, and much the same effect is observable if insects be subjected to too low a temperature. Under normal conditions of food and temperature a silkworm weighs, when fully grown, up to 10,500 times its weight when just hatched, and the caterpillars of the goat moth during a life of three years are stated to increase 72,00o times in weight in that period.

Hypermetamorphosis.—When an insect passes through two or more markedly different larval instars it is said to undergo hypermetamorphosis. This phenomenon is accompanied by a marked change in the life of the larva concerned. In most cases where this happens, the first larval instar is active and campodei f orm, and in this condition the insect seeks its food. Having dis ;overed its pabulum it undergoes changes of form which adapt it o its subsequent mode of life. Hypermetamorphosis is evident n some beetles (see COLEOPTERA), in certain flies, in most of the ;roups of parasitic Hymenoptera (q.v.) and in some other insects. Pupa.—Near the end of the larval period the insect prepares tself for transformation into the pupa, usually constructing a :ocoon or other type of protection. A preliminary period of luiescence then follows when the insect is in a condition termed he pre-pupa (fig. 37). In this stage the wings and appendages irst become evident outside the body, and its general form fore shadows that of the imago. The pre-pupa is loosely enclosed in the old larval skin, and after the latter is moulted the true pupal condition is assumed. Since the pre-pupal and pupal instars are particularly vulnerable, either protection or concealment is neces sary. It is only rarely that pupae are quite exposed as happens in those of many butterflies, but, in this case, protection is afforded by their colouration, which often closely assimilates with the natural surroundings. The larvae of many moths and beetles bur row in the ground when about to pupate, and then transform within earthen cells composed of soil particles, held together by an adhesive secretion. Numerous other insects construct cocoons of various extraneous materials woven together with a warp of silk, while in many moths the cocoons are formed entirely of silk : some of the most elaborate cocoons are those constructed by the great silkworm moths of the family Saturniidae. Among true flies there is seldom a cocoon and in those with a coarctate pupa, the latter is protected by being concealed below the soil, in refuse or other situations where the lar val life was passed.

The term pupa is applied to the resting, passive stage in the life I of insects with a complete meta morphosis, and during this instar it is incapable of feeding. The pupa is an acquired transitional phase during which the developing wings, legs and other append ages of the future insect appear outside the body. Three types of pupae are generally recognized. In the free pupa (figs. 34 and 37) the wings and legs are free from any secondary attachment to the body, and such pupae have considerable capacity for move ment. In mosquitoes and midges the pupae are aquatic, and are active swimmers : in certain other insects they are able to work their way above ground to facilitate the emergence of the perfect insects. The obtected pupa (fig. 33) has the wings and legs glued down to the body and there is but little freedom of movement : this type is characteristic of most moths. The coarctate pupa (fig. 36) is found in all the higher groups of flies. In these insects the last larval skin is not cast off but remains outside the pupa as a hardened shell forming a capsule or puparium.

Emergence from the Pupa.

As the time approaches for the eclosion of the perfect insect the pupa noticeably darkens, and in many butterfly pupae, the colours of the contained insect are dis tinctly observable at this time. During the act of emergence the insect usually ruptures the pupal cuticle in a longitudinal fracture down the back of the thorax, and draws itself out. It then crawls up the nearest available support and rests with its miniature wings hanging downwards. By the influx of blood from the body the wings assume their full size and, after a period of rest when all the parts become hardened, the insect is able to make its first flight. When a cocoon is present the insect often has to bite its way through the walls by means of its jaws as in Coleoptera and Hy menoptera, but in caddis-flies and Neuroptera, the pupa bears mandibles for this purpose ; various other methods of emergence from the cocoon are mentioned in the article LEPIDOPTERA.

Development of the Perfect Insect.

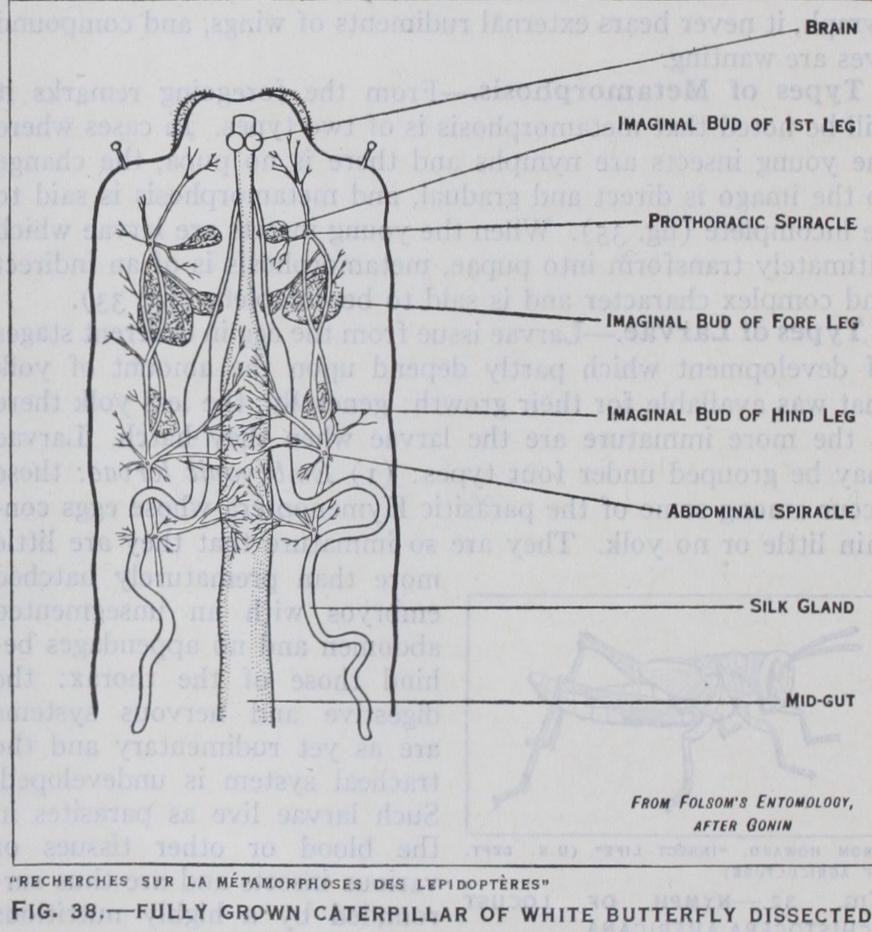

The culminating point of metamorphosis is the actual formation of the imago. In insects with incomplete metamorphosis this is accomplished by a gradual process of growth changes, both internal and external, during suc cessive nymphal instars till the adult condition is attained. In insects with complete metamor phosis, it has been seen that a pupal stage has been intercalated in the life-cycle, and it is dur ing this instar that profound change occurs. Outwardly inac tive, the pupa is in reality the seat of intense activity within. The formation of the imago be gins in the larva and is initiated by the development of new growths termed imaginal buds, which gradually build up all the parts that require reconstruction to serve the needs of the future insect, as well as forming all or gans unrepresented in the larva. Imaginal buds which form the legs, wings, mouth-parts and other external organs, are derived from the hypodermis and some of them can be seen by careful dissection of a fully grown cater pillar (fig. 38). The buds which form the internal organs arise from nests of cells in special lo cations within the existing larval organs, and by their growth and extension build up the new parts necessary. In some insects such as beetles and Neuroptera the in ternal changes are often relatively simple, but in ants, bees and many flies they are extremely com plex. It is during the pupa that the unwanted larval organs have to be broken down and replaced by new growths, and the amount of reconstruction required de pends upon how far the structure and functions of the imago differ from those of the antecedent larva. In the blow-fly, for ex ample, practically all the larval organs are broken down in the pupa, and their residue, as it were, serves as nutriment for devel oping new growths. The actual method of destruction of the larval organs has given rise to much discussion, but most authorities maintain that wandering blood cells, or phagocytes, play an active part, and in fig. 39 are seen certain of the phagocytes destroying a larval muscle. In other insects it is believed that phagocytes either perform a less important part in the process, or take no part at all, and that physiological changes induce the organs con cerned to degenerate and break down.The number of described species of insects exceeds 450,000 and though several thousand new ones are discovered yearly, it is believed that the unknown species remain an enormous majority. The classification of this vast assemblage of forms has undergone many changes since Linnaeus' time, though five of his orders are recognized to-day. Most of the classificatory schemes that have been proposed are based primarily upon characters afforded by the mouth-parts, wings and metamorphosis. As many as 37 dif ferent orders are adopted by some authorities, but the most gen erally accepted systems are more conservative in this respect. The classification here adopted includes the following 23 orders (an asterisk indicates a separate article on the subject).