Later Pre-Maurya

LATER PRE-MAURYA vessel or vase of plenty (purna kalasa) of India, the former sig nificantly spoken of by Heuzy as the "merveilleux symbole qui etait comme le Sainte-Graal de 1'epopee chaldeenne," and both of importance in connection with the origins of the Grail cult. To these may be added similarities of technical procedure, as in the process of decorating carnelian by calcining and in the sim ilar composition of Indian and Assyrian glass.

Neither the archaeological nor the mythological evidence sug gests that either the Mesopotamian or early Indian cultures have been derived from the other, or has borrowed extensively from the other at any one period, but rather that both have developed in situ, though not without intercourse and contact, on the corn mon basis of the early chalcolithic culture which in the fifth and fourth millennia B.c. extended over an area extending from the Adriatic to Japan, and can be associated with the dolichocephalic "Mediterranean" races of southern Asia and Europe and attained its fullest development in the great river valleys of the Nile, Eu phrates and Tigris, Karun, Helmund, Indus and perhaps the Ganges. According to one not unreasonable conjecture, the orig inal focus of this culture may have been in Armenia, a country rich in metals and possibly the starting point of early race move ments across the highlands of Persia in one direction towards Elam and southern Mesopotamia, in the other towards central Asia and India. Many years of work in this comparatively novel field of research will be required before more definite conclusions can be advanced.

Vedic and Pre-Maurya.

It will be assumed that the Ar yans entered India from the North-West, about 1500 B.C., and oc cupying the Panjab, had gradu ally passed on to the Ganges valley. They probably brought with them a knowledge of iron, and a superior breed of horse, and it may have been these ad vantages that enabled them to subjugate the existing peoples who already possessed cities and forts, and a more developed ma terial civilisation. After the first period of conflict, the Aryans (as with the later invaders, Scyth ians, Huns and Mughals) ceased to be foreigners, and became Indians : long before 500 B.C., northern India had become the seat of a mixed culture in which, and especially in the art, both as regards its motifs, and its technical achievement, the non Aryan element predominated. The conquerors had been con quered by the conquered.Vedic literature, mainly in the relatively later texts, reveals a knowledge of tin, lead, silver, .gold and iron, of cotton, silk, linen, and woollen garments, sometimes embroidered, vessels of Few sites likely to yield remains of this period have been ade quately excavated. The later strata of Mohenjo-Daro probably come down to 400 B.C. The greatest number of pre-Mauryan antiquities has been obtained at the Bhir mound, Taxila; most notable are the finely wrought polished sandstone discs, with bands of concentric ornament, in which are found cable, cross and bead, and palmette motifs, the taurine symbol, elephants, fan palms, and the nude goddess.

It is also certain that the cutting and polishing of hard stones, and the technique of glassmaking had attained already in the fourth and fifth centuries B.C. a perfection never afterwards sur passed ; and when in the Maurya period we first meet with stone sculptures, we find the surface of the hard stone highly polished. One other important type of early art is represented by the punch marked coin symbols; these coins were in use from about 60o B.C. to A.D. I oo. The marks include some hundreds of types; amongst the commonest are the mountain (usually with three or more peaks—the so-called caitya of older numismatists), river or tank with fish, sacred tree, elephant, horse, bull, sun, moon, "caduceus," "taurine"; the lion, rhinoceros, makara, and human figure are rarer. No lingam, thunderbolt, foot-marks or stfipa is represented. These signs (rupa), forming an extensive symbolic repertory, appear to have been those of issuing and ratifying authorities. Many of the symbols are those of particular deities ; for example, the three-peaked mountain with moon crescent is otherwise known to have been a symbol of Siva, and so also the bull. Few or none of the marks are exclusively Buddhist. Some are connected with particular cities, and in their day identified the issuing mints.

As regards design the same forms which are found in the re liefs of the Maurya, Sunga, and Andhra periods were already current during many centuries before the fourth B.C. These forms include meanders, palmettes, vases with flowers, sacred trees, diapers, spirals, frets, twists and the like, animals addorsed or affronted, and fantastic animals of all kinds. Many or all of these characteristic forms are clearly related to, but not iden tical with, Mesopotamian types, Assyrian or older. They consti tute a common ground of early Asiatic, and in India are cognates of the Mesopotamian forms, not late borrowings. The fact that we find them extant only in the stone sculpture when it first appears in the Maurya period is of course no proof of their late origin; some of the most ancient survive most characteristically in quite modern folk-art, and may well have been current during three or four millennia. Thus, the motif of animals with interlacing necks, known in Ceylon as piittuva, where it is one of the com monest motifs of the folk art, was already current in Sumerian art of the fourth millennium B.C., and very many other instances of the same kind could be cited.

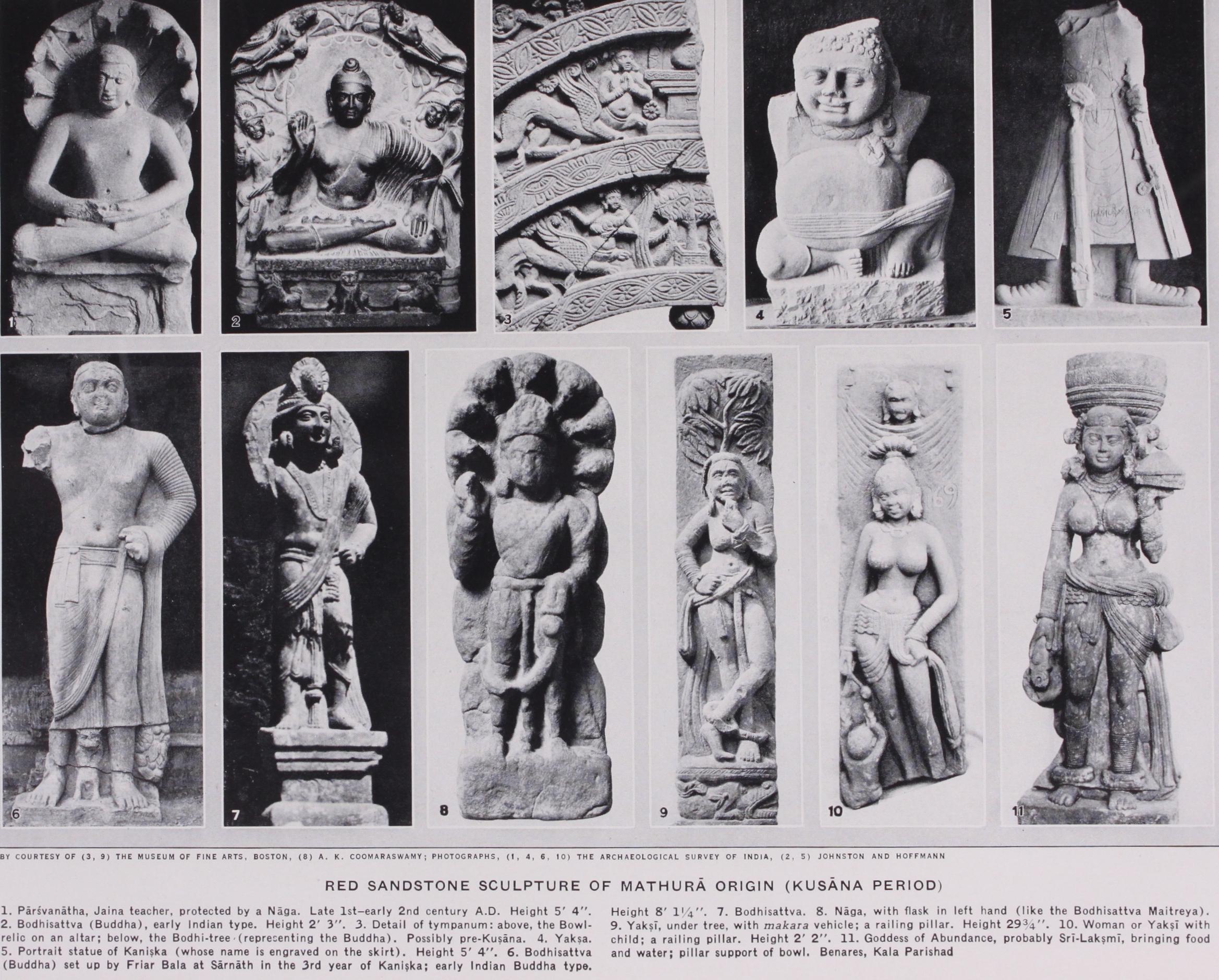

As regards sculpture, late Vedic literature, in which a large non Aryan element has been absorbed, affords evidence for the mak ing of images of popular deities in impermanent materials ; and it is certain that the earliest known stone figures (after the Indus valley types), viz., the Yaksas of the Maurya and Suriga periods, despite their retention of primitive qualities (frontality, etc.), are not first efforts in any sense ; they represent an already advanced stage in stylistic and technical development. We have also the evidence of pre-Maurya terracottas representing the nude god dess and some other types. The latter are of very great impor tance for the history of art, for though they belong to a stylistic cycle older than that of the stone sculpture, and are still too little known, they provide connecting links between the oldest Indo-Sumerian art and that of the historical period, in style, technique, and costume. In their sense of the inseparable con nection of beauty and fruitfulness, and in details of ornament (the body ornament later known as the cltannavira, and the broad auspicious girdle, mekhala) as well as in some facial types, they connect with the earliest sculptures in stone.