Miall Fig

MIALL FIG. 3 -FRONT VIEW OF HEAD OF COCKROACHFig. 3 -FRONT VIEW OF HEAD OF COCKROACH ened cuticle or outermost layer of the integument or body-wall. It is composed of a substance termed chitin and is produced by the hypodermis or cellular layer of the integument. The skeleton remains membranous and unchitinized at the joints or other places where movement occurs, but over the rest of the body it is composed of separate areas or sclerites which meet along definite lines or sutures : in cases where adjacent sclerites are fused the sutures are obliterated. Like other Arthropods, insects are seg mented animals and a segment consists normally of a dorsal re gion or tergum, a lateral region or pleuron on each side, and a ventral region or sternum—each region being composed of one or more sclerites. Typically, a segment bears a pair of jointed ap pendages or limbs attached on either side between the sternum and the pleuron (fig. 2) ; these appendages are modified according to the various functions they perform and are absent from most of the abdominal segments. In addition to forming the skeletal covering, the integument also produces the hairs, scales, spines and other external structures.

Colouration.

Many of the colours of insects are due to pig ments which occur in the cuticle, or below the cuticle in the hypodermis, or in the blood. Pigmentary colours are mostly reds, yellows, browns and blacks, but very rarely blues, and are pro duced as the result of chemical changes that go on in the body of the insect. The experiments of F. Merrifield and others have shown that they are often greatly influenced by heat or cold and other means. Some pigments are excretory products and, in the cabbage white butterflies, the white scale colour is due to uric acid and certain yellows, reds and possibly greens, of other butter flies and moths and derivatives of this same substance. The yel lows, greens and reds of many caterpillars are derived from the chlorophyll of the food, which enters the blood and the colora tion is due to their visibility through the integument. Certain blacks and browns are of the nature of melanins and are induced by an oxidase. It is noteworthy that the pigments of many butterflies and moths are brilliantly fluorescent when subjected to ultra-violet light in a completely darkened room.

Other colours are the result of structural features that bring about interference; in a number of cases fine parallel ridges or striae on the scales produce iridescent colours. In some instances, as in Lycaenid or blue butterflies, little or no pigment may be present, while the metallic greens, blues and coppers of other insects are produced by scale-structure in combination with a backing of pigment. Very often this pigment is black, but the emerald green of an Ornithoptera butterfly has been shown to be due to scale structure combined with yellow pigment in the walls of the scales. The golden iridescence of Cassida beetles is produced by a film of moisture beneath the surface cuticle and is quickly lost after death.

Head.

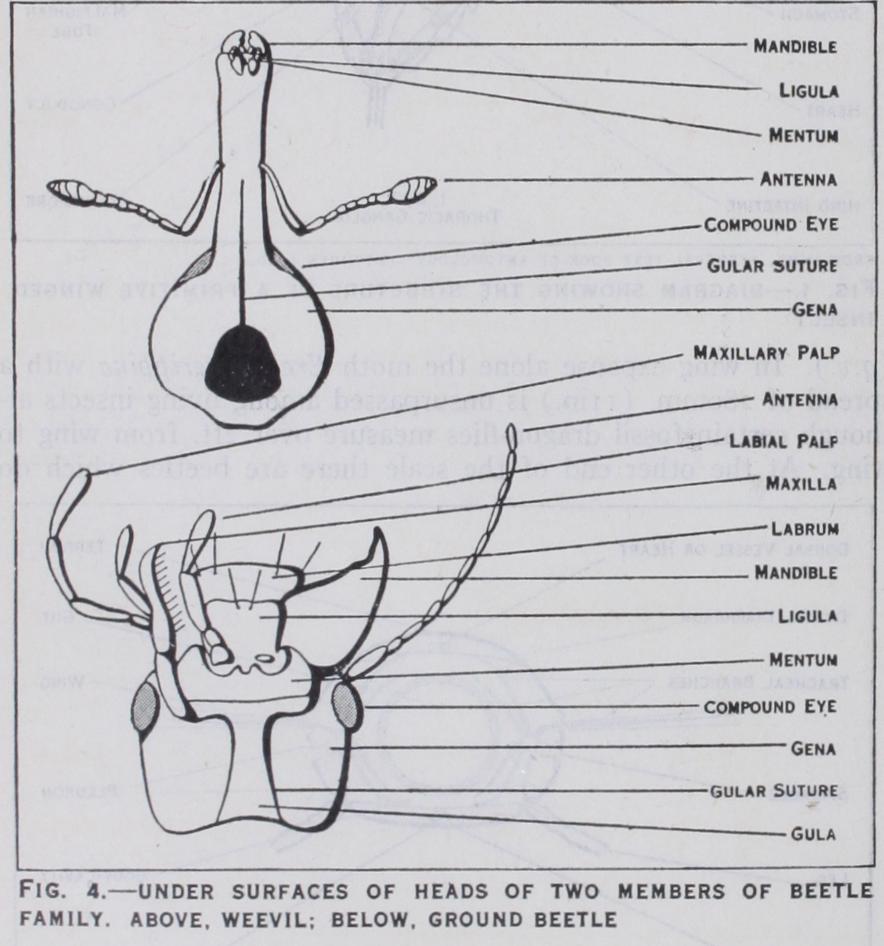

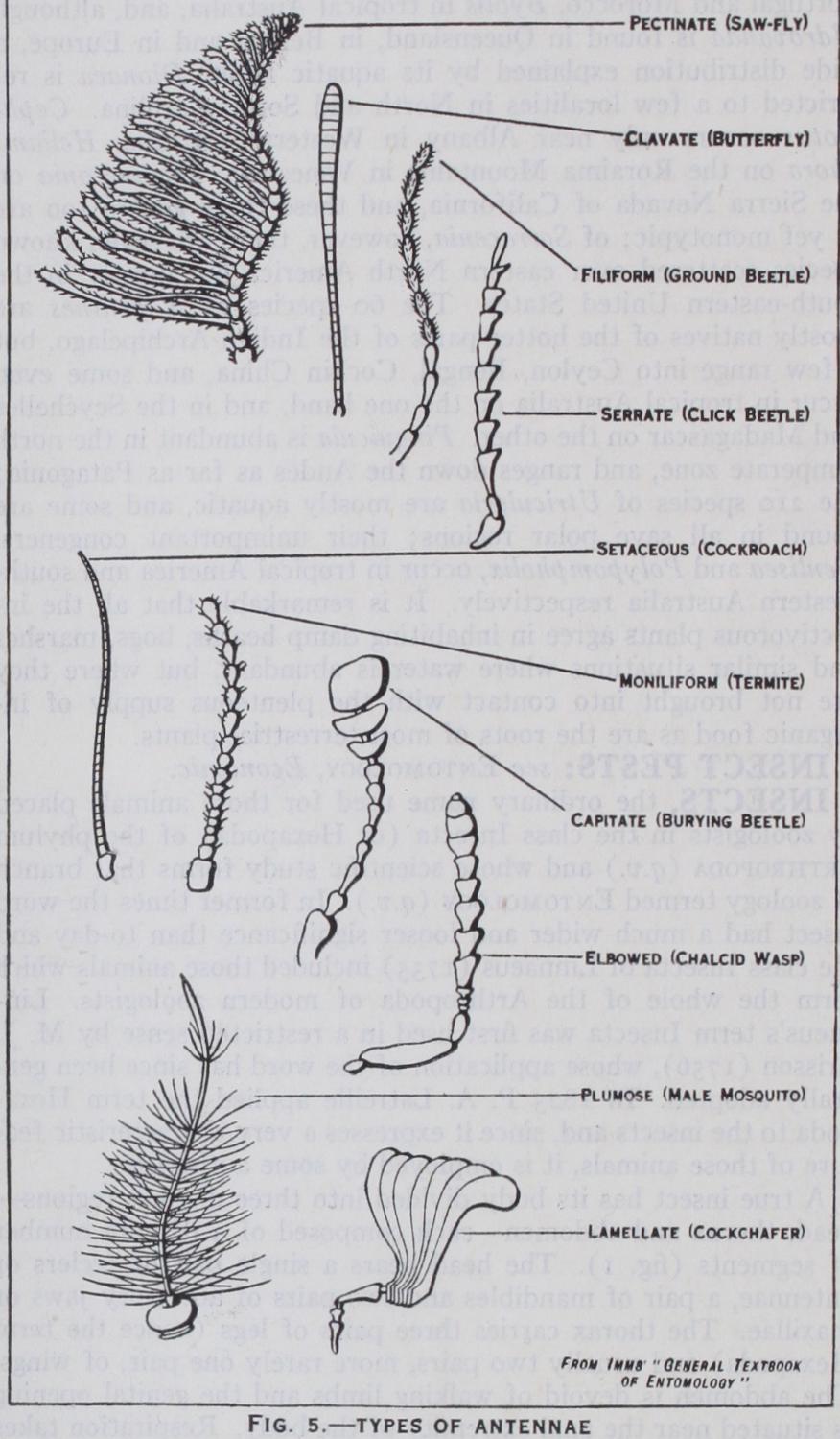

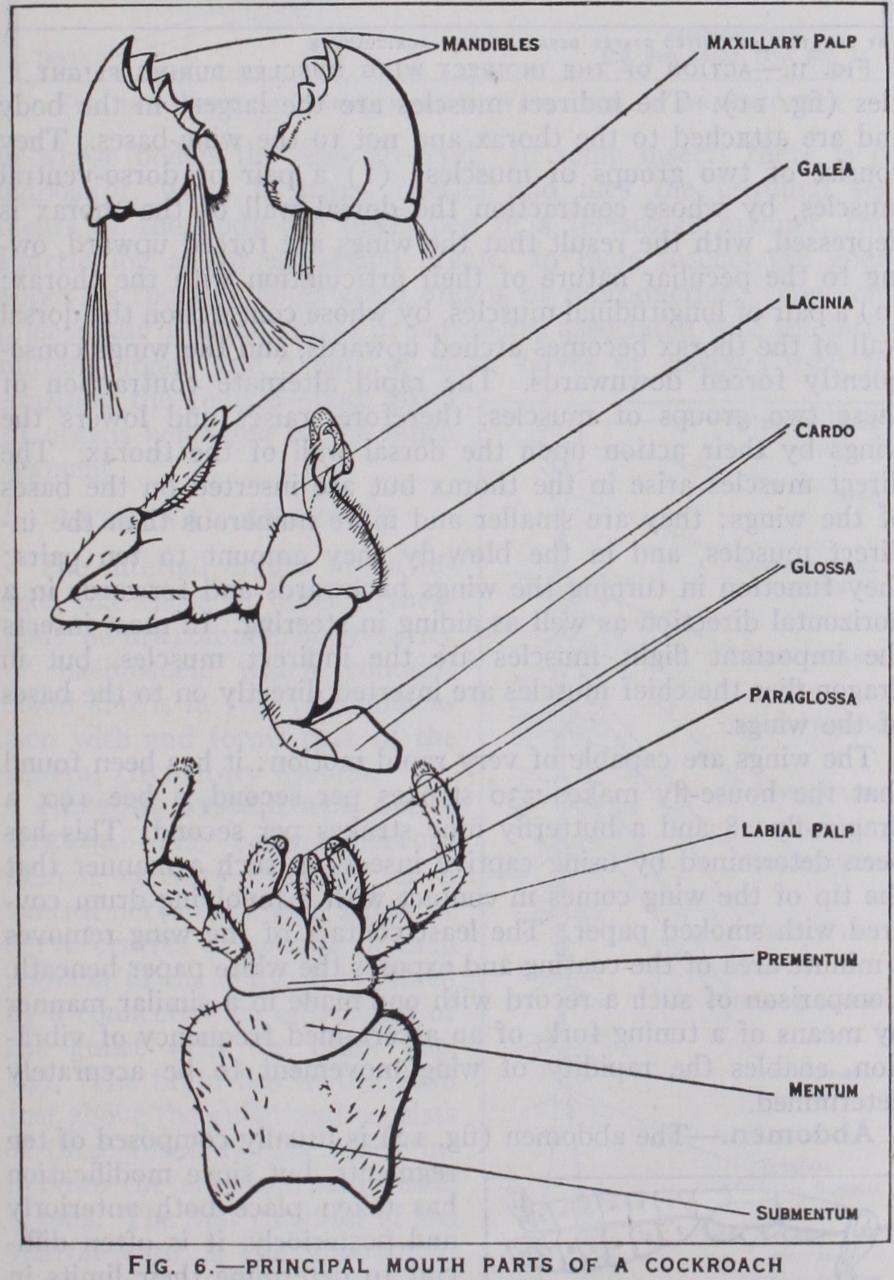

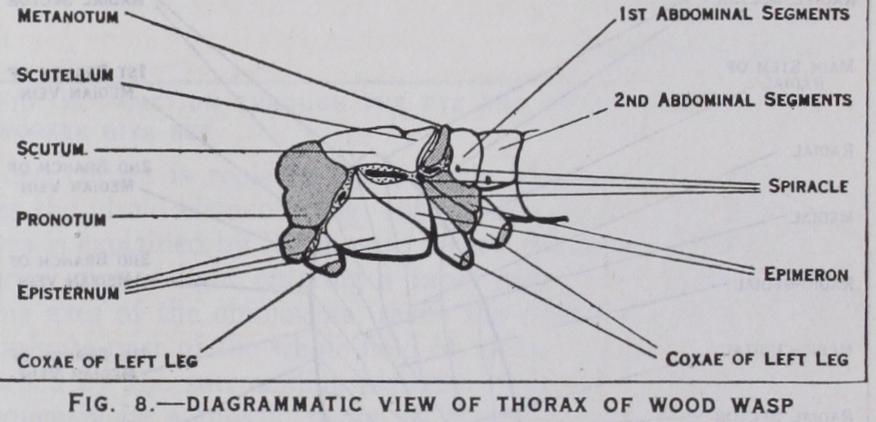

The head (figs. 3 and 4) is composed of six segments which are so intimately fused together that evidence of its seg mental structure is chiefly derived from the presence of append ages. On the upper surface of the head of a cockroach or other generalized insect a Y-shaped epicranial suture is present, the sclerite between the arms of the Y being the frons, while behind the frons the rest of the head is termed the epicranium. Anterior to the from is the clypeus, which is often fused with it, and in front of the clypeus is a movable upper lip or labrum; the inner sensory lining of the labrum is termed the epipharynx, which, along with the labrum, is often greatly developed in sucking insects. Paired compound eyes are almost always present on the epicra nium and below the eyes are the gene or cheeks: three simple eyes or ocelli are also frequently evident. The head is attached to the thorax by a neck and the region of attachment is indicated by the large occipital foramen: on the floor of the head in front of this foramen there is sometimes present a median chin sclerite or gala (fig. 4) . The head bears four pairs of appendages— antennae, mandibles, first maxillae and second maxillae. The an tennae or feelers are composed of a variable number of joints or segments and are very diverse in form : they bear sense organs of smell and touch and are often more conspicuously developed in the male than in the female (fig. 5). The mandibles (figs. 3 and 6) are the principal jaws and are used for seizing and crushing the food. The first maxillae are accessory jaws; each maxilla con sists of two basal pieces, cardo and stipes, the latter bearing an outer lobe or galea and an inner toothed lobe or lacinia. Exter nally the maxilla carries a jointed maxillary palp which bears organs of special sense. The second maxillae form the lower lip or labium and are composed of a pair of partially fused append ages. Its large basal plate or sub-mentum is joined in front with the mentum and the latter carries the pre-mentum which shows indications of a paired structure. The pre-mentum when pletely developed carries paired lobes on either side ; these lobes are the paraglossae and glossae which are homologous with the galeae and laciniae of the first maxillae. Collectively they form the ligula, but often one or both pairs of these lobes are wanting or fused. Jointed labial palpi arise on either side from the outer border of the pre-mentum. On the floor of the cavity, above the base of the ium, is the tongue or ynx, which receives the opening of the salivary duct ; in the more primitive insects and some vae, paired lobes—the linguae (maxillulae)—are present in relation with the hypopharynx. The mouth parts of insects present many modifications of form in accordance with the uses to which they are subjected. Thus, in insects which feed by sucking, the galeae of the lae are prolonged into a cis, and in piercing insects the mandibles, maxillae and other organs are developed into needle-like stylets. These and other modifications are dealt with under the separate groups concerned. Thorax.—Three segments make up the thorax which is the locomotory centre of the body : they are termed the prothorax, mesothorax and metathorax. The tergum of the prothorax is formed by the pronotum, and although large in cockroaches, plant bugs and beetles is usually reduced in other winged insects. In the mesothorax and metathorax the tergum is made up of a series of sclerites, one behind the other; viz., prescutum, scutum, scutellum and post-scutellum (fig. 7)—of these the scutellum of the mesothorax is often especially prominent. Laterally each pleuron is composed of an anterior sclerite or episternum and a posterior sclerite of epimeron (fig. 8). On the ventral side, each sternum is composed of variable numbers of sclerites in differ ent groups.

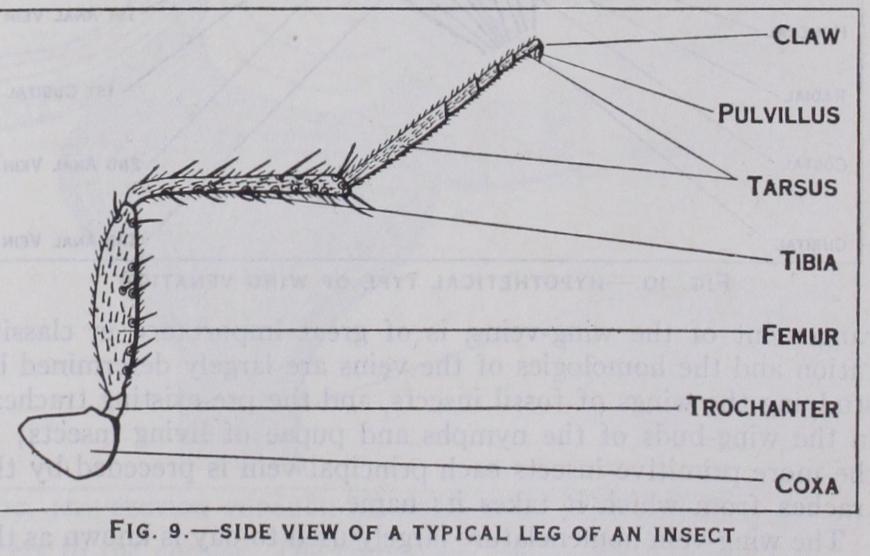

Legs.

A pair of legs is borne on each thoracic segment. A leg is formed of five parts (fig. q) ; viz., a broad subglobular coxa which articulates with the thorax; a small trochanter; a stout elongate femur; a slender tibia; and a tarsus consisting typically of five segments or joints. The last tarsal segment bears a pair of claws, more rarely a single claw, and beneath the claws there is a pair of adhesive pads or pulvilli which aid in walking over steep or smooth surfaces. Legs vary greatly in form according to whether they are used for running, burrowing, grasping, etc.Locomotion.—While walking an insect usually moves its legs in such a way that the fore and hind legs of one side, and the middle leg of the other side, progress forward almost at the same moment, the body being supported, as it were, on a tripod formed by the remaining three legs. The anterior leg pulls the body forward and the hind leg chiefly pushes in the same direction, while the middle leg steadies the body and helps to raise or lower it.

Wings.

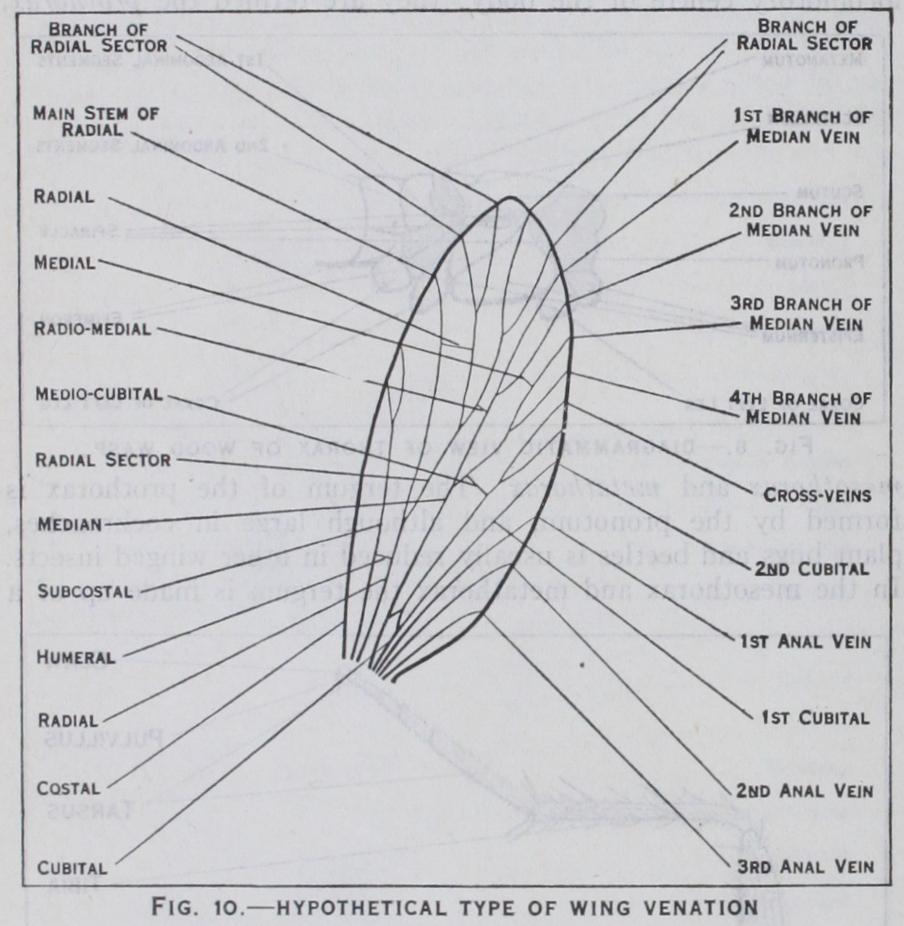

Wings are lateral outgrowths of the integument of the tergum of the meso- and metathorax and commence to de velop in the larva or nymph as the case may be. They exhibit great variety of form and structure in different groups of insects and may be wanting altogether: some insects, such as bristle tails and spring-tails, have never acquired wings, while others such as lice, fleas, worker ants, etc., although wingless, are be lieved to have been derived from winged ancestors. A wing is composed of an upper and a lower membrane and between these two layers it is strengthened by a framework of chitinous tubes known as veins. The latter develop very largely in relation with the air-tubes or tracheae which enter the developing wing when it is little more than a bud-like outgrowth. The venation, or ar rangement of the wing-veins, is of great importance in classifi cation and the homologies of the veins are largely determined by studying the wings of fossil insects, and the pre-existing tracheae in the wing-buds of the nymphs and pupae of living insects; in the more primitive insects each principal vein is preceded by the trachea from which it takes its name.

The wing-vein nomenclature largely used to-day is known as the Comstock-Needham system. It is based upon the conclusion that all orders of winged insects have a venation derived from a common primitive type and that there are eight principal veins. These veins and their recognized symbols are shown in fig. Io. The actual venation, it must be understood, departs by a greater or lesser degree from this primitive plan and either reduction or multiplication of the veins and their branches is the rule. Be tween the veins are cross-veins which divide the wing into closed areas or cells, each cell taking its name from the vein which forms its anterior boundary.

Flight.

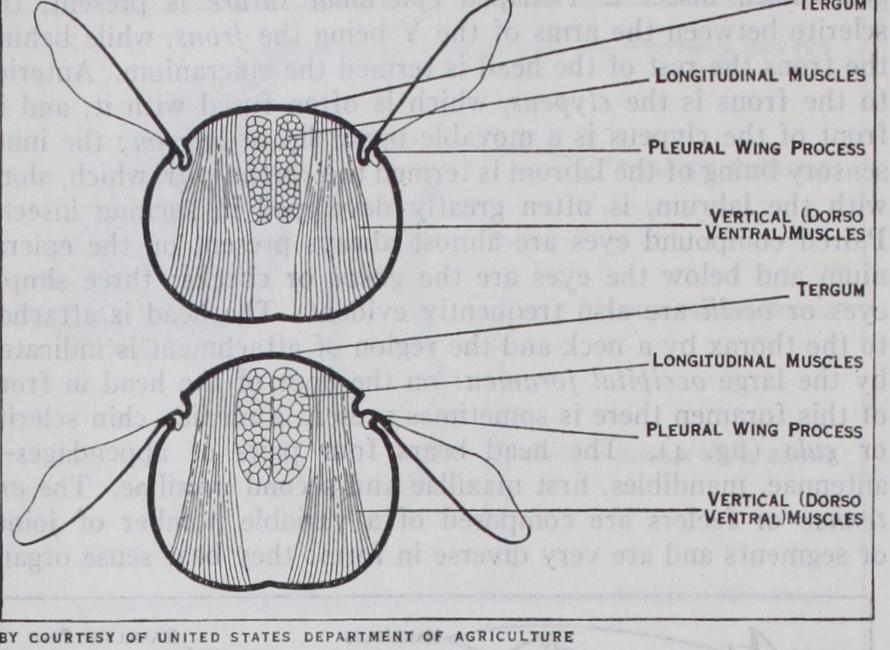

During flight the wings of an insect have an up-and down motion combined with movement in the backward and for ward directions. This results in the path or trajectory made by the apex of the wing taking the form of a continuous series of double loops resembling the figure 8. These movements are ef fected by two sets of muscles—indirect muscles and direct mus FIG. 11.-ACTION OF THE IN^!RECT WING MUSCLES DURING FLIGHTFig. 11.-ACTION OF THE IN^!RECT WING MUSCLES DURING FLIGHT Iles (fig. I I). The indirect muscles are the largest in the body and are attached to the thorax and not to the wing-bases. They consist of two groups of muscles: (I) a pair of dorso-ventral muscles, by whose contraction the dorsal wall of the thorax is depressed, with the result that the wings are forced upward, ow ing to the peculiar nature of their articulation with the thorax; (2) a pair of longitudinal muscles, by whose contraction the dorsal wall of the thorax becomes arched upwards, and the wings conse quently forced downwards. The rapid alternate contraction of these two groups of muscles, therefore, raises and lowers the wings by their action upon the dorsal wall of the thorax. The direct muscles arise in the thorax but are inserted on the bases of the wings: they are smaller and more numerous than the in direct muscles, and in the blow-fly they amount to ten pairs; they function in turning the wings backwards and forwards in a horizontal direction as well as aiding in steering. In most insects the important flight muscles are the indirect muscles, but in dragon-flies the chief muscles are inserted directly on to the bases of the wings.

The wings are capable of very rapid motion : it has been found that the house-fly makes 33o strokes per second, a bee Igo, a dragon-fly 28 and a butterfly nine strokes per second. This has been determined by using captive insects in such a manner that the tip of the wing comes in contact with a revolving drum cov ered with smoked paper. The least contact of the wing removes a minute area of the coating and exposes the white paper beneath. Comparison of such a record with one made in a similar manner by means of a tuning fork, of an ascertained frequency of vibra tion, enables the rapidity of wing movement to be accurately determined.