Order Iii Siphonophora

ORDER III. SIPHONOPHORA The Siphonophora constitute one of the most interesting groups of the animal kingdom, since they illustrate the lengths to which an organism may go in the direction of stringing together a num ber of different kinds of individuals in a single chain. In scien tific terminology they exhibit at its height the phenomenon of polymorphism.

The Siphonophora, unlike the Hydroida, are essentially pelagic animals: they are exclusively marine, and most characteristic of warm seas. They one and all form colonies, but the colony is unattached and either floats or swims. It produces sexual medusae comparable to those of a hydroid, and these may or may not be set free from the colony; quently there may be an alternation of erations, both pelagic, or the eration may never gain independent istence. There is however this ence from the state of affairs among the Hydroida, that a medusa which is set free as such is an exception, and that it has never the full structure of a Hydroid dusa, possessing no mouth or sense-organs. Most siphonophore medusae remain tached to the colony or to a segment of it, and many of them exhibit grades of tion in structure. These are known as gonophores, but they are never as erate as a Hydroid sporosac. From the eggs produced by the medusae or gonophores a planula larva of a curious type develops, and this by budding produces a colony. The siphonophore trasts with a trachyline in that it is here the colony, and not the sexual medusa, which is the dominant form ; and in addition to this a new factor is introduced which is not found either in the lina or in the Hydroida. This is the production by the colony not only of more than one kind of polyp (as in Hydractinia) but also of more than one kind of medusa. In addition to the sexual me dusae corresponding to the sole medusa-form in the other groups, there are found here medusae of modified structure which neither feed nor produce gonads, but which act as swimming-bells for the whole colony ; and other structures which are also probably modi fied medusae. Of these latter one is a medusa transformed into a gas-containing float.

Structure of Colonies.

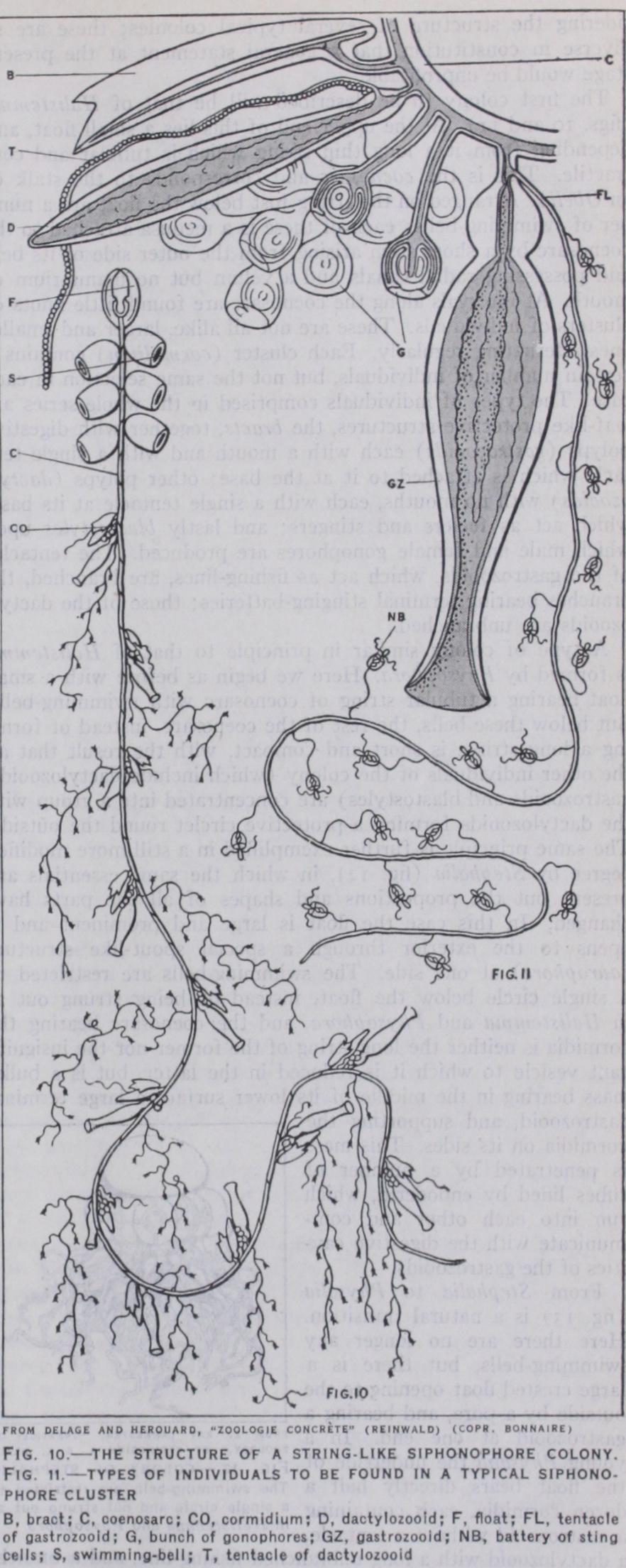

It will be impossible to understand or to visualize the siphonophore organization, without first con sidering the structure of several typical colonies; these are so diverse in constitution that a general statement at the present stage would be unprofitable.The first colony to be described will be that of Halistemma (figs. Io and I I). At the upper end of this lies a small float, and depending from it a long thin string which is tubular and con tractile. This is the coenosarc and corresponds to the stalk of an Obelia. Arranged on the string just below the float are a num ber of swimming-bells; each of these is a medusa attached to the coenosarc by a short stem arising from the outer side of its bell, and possessing radial canals and a velum but no manubrium or mouth. At intervals along the coenosarc are found little knots or clusters of individuals. These are not all alike, larger and smaller ones alternating regularly. Each cluster (cormidium) contains a certain number of individuals, but not the same selection in each case. The types of individuals comprised in the whole series are leaf-like protective structures, the bracts, together with digestive polyps (gastrozooids) each with a mouth and with a single ten tacle which is attached to it at the base; other polyps (dactyl ozooids) with no mouths, each with a single tentacle at its base, which act as feelers and stingers; and lastly blastostyles upon which male and female gonophores are produced. The tentacles of the gastrozooids, which act as fishing-lines, are branched, the branches bearing terminal stinging-batteries; those of the dactyl ozooids are unbranched.

A type of colony similar in principle to that of Halistemma is formed by Physophora. Here we begin as before with a small float bearing a tubular string of coenosarc with swimming-bells. But below these bells, the rest of the coenosarc, instead of form ing a long string, is short and compact, with the result that all the other individuals of the colony (which include dactylozooids, gastrozooids and blastostyles) are concentrated into a group with the dactylozooids forming a protective circlet round the outside. The same principle is further exemplified in a still more modified degree by Stephalia (fig. 12), in which the same essentials are present but the proportions and shapes of all the parts have changed. In this case the float is large and prominent and it opens to the exterior through a special spout-like structure (aurophore) at one side. The swimming-bells are restricted to a single circle below the float, instead of being strung out as in Halistemma and Physoplrora, and the coenosarc bearing the cormidia is neither the long string of the former nor the insignifi cant vesicle to which it is reduced in the latter, but is a bulky mass bearing in the middle of its lower surface a large terminal gastrozooid, and supporting the cormidia on its sides. This mass is penetrated by a number of tubes lined by endoderm, which run into each other and com municate with the digestive cav ities of the gastrozooids.

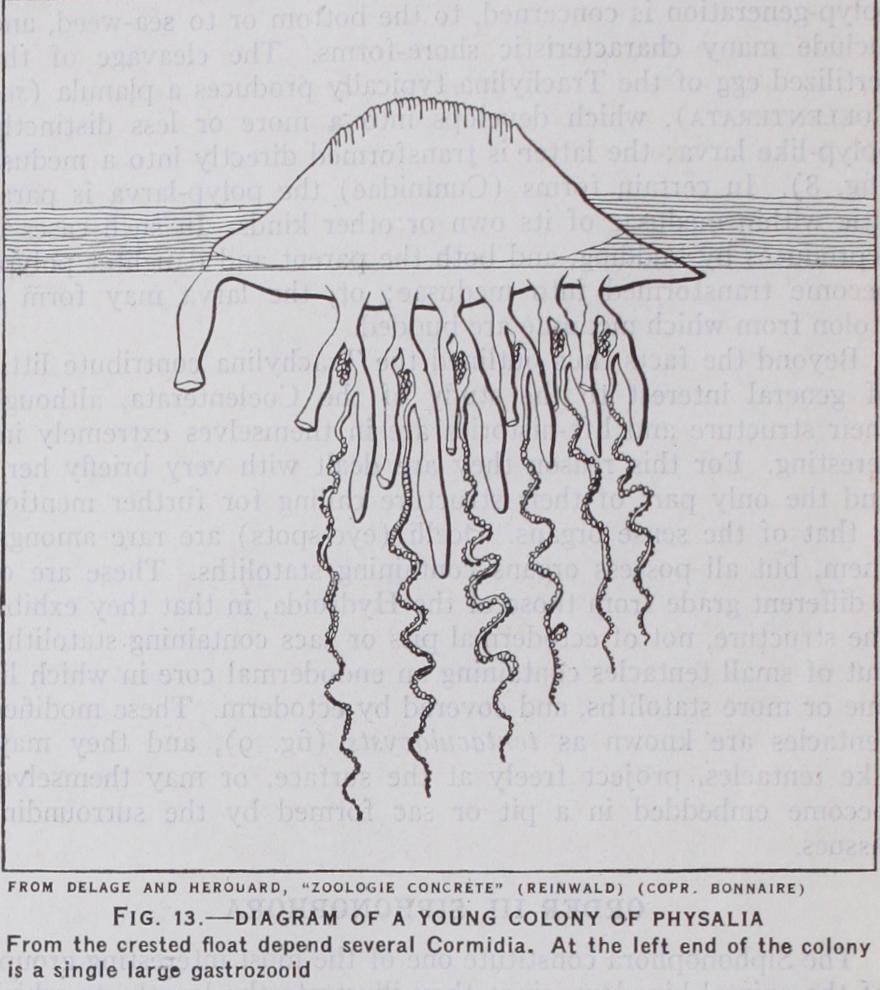

From Stephalia to Physalia (fig. 13) is a natural transition.

Here there are no longer any swimming-bells, but there is a large crested float opening to the outside by a pore, and bearing a gastrozooid at one end. In a young Physalia the underside of the float bears directly half a dozen cormidia, each containing a gastrozooid without a tentacle, a dactylozooid with a long unbranched fishing-line, and a branch ing blastostyle bearing small dactylozooids upon it, and also male and female gonophores. As the colony increases in size new indi viduals are added somewhat irregularly upon the stalks of the old, and the simple early arrangement is lost. The colours of Physalia (blue, orange, etc.) are of great brilliance, and it is a well-known denizen of the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans, often occurring in fleets, and commonly known as "Portuguese Man-of-War." One of its fishing-lines reaches a greater length than all the others, at taining more than a yard; and the stinging powers of these lines are extremely powerful, producing serious conditions after contact with them even in man. The colony is not bound to float at the surface; it can deflate the float and sink, reforming the gas within it and so rising once more, within a quarter of an hour.

A colony quite unlike any so far described is formed by Velella. Here the whole organism has the aspect at first sight of a single flat medusa bearing a sail on its upper side and tentacles round its margin (fig. 14). On closer examination it is found, however, that the apparent tentacles are really a circle of long dactylo zooids, and that the underside of the disc-like colony is covered by a number of curious blastostyles which, unlike an average blastostyle, possess mouths. In the centre of these is a single large gastrozooid, the only one which the colony possesses. The disc-like portion of the animal to which all these polyps are attached is complex in structure. It is thick and contains below the skin-layers of its upper side an internal horny float, below which is a mass of soft tissue, a concentrated coenosarc. The float is itself flattened in shape, is subdivided into chambers, bears a vertical extension in the centre stiffening the "sail," and is pro longed into the soft tissues as fine air-tubes. The coenosarc con tains a ramifying system of endodermal tubules, in communica tion with the cavities of the various polyps, which is probably both absorptive and excretory in function. The coenosarc also contains a massive concentration of nematocysts, doubtless a nursery whence they migrate when sufficiently developed into the parts where they can function. Very similar to Velella but with out a sail, is Porpita. In these creatures we have reached a stage in which the colony has become so compact and the parts so markedly subordinated to the whole that their interrelation resembles rather that of organs than that of independent beings; but free medusae are liberated by the colony.

Finally it may be mentioned that there are a number of siphonophore colonies which differ from any so far mentioned in that they possess swimming-bells but no float.

We may now summarize the state of affairs in this very curious group of animals. In the course of the above descriptions men tion has been made of a number of structures—gastrozooids, blastostyles, dactylozooids; swimming-bells, floats, bracts; and sexual medusae (fig. II). It remains to comment on the status of these various entities. Continuing the view which is taken throughout the articles on Coelenterata in this Encyclopædia, most or all of these structures represent individuals, modifications of either the polyp or the medusa form of body, or independently developed entities of equivalent standing. The gastrozooids and dactylozooids are varieties of polyp, the sexual medusae, the swim ming-bells, and probably the bracts are modifications of medusae. The float is sometimes regarded as the invaginated upper end of the stem of coenosarc, and sometimes as a modification of a medusa. The status of the blastostyles is uncertain ; they repre sent polyps in V elella-, in other cases they are perhaps the present day substitute for bygone polyps.

It should be mentioned in conclusion that the Siphonophore is regarded by Moser not as a colony of individuals but as an indi vidual animal with division of labour between organs and "on the way to alternation of generations and to colony-formation"; and that the medusae of V elella are regarded by this author as free swimming gonophores leading up to true sexual medusae. The work of Moser has thrown considerable light on the morphology and the development of the Siphonophora, and has made clearer than formerly the homologies of parts throughout the group, espe cially that of the float, which may fairly be regarded as equiva lent to the apical adult bell of the forms with no float. This work also forms a valuable contribution to the question of evolution within the Siphonophora, but in the view of the present writer it hardly establishes the claim that a siphonophore is an individual animal (see also the following section on Polymorphism) .