Paints and Varnishes Wax Finish and Painting Early American Period Chinese Japanese Modern Wood Finishes

EARLY AMERICAN PERIOD; CHINESE; JAPANESE; MODERN; WOOD FINISHES, PAINTS AND VARNISHES; WAX FINISH AND PAINTING.

Early Middle Ages.

In the earliest middle ages domestic life, such as we understand it, can hardly be said to have existed at all. Furniture and equipments had to be of a kind convenient for trans port from one place to another. They were solid and strong, and in number they were kept down to the indispensable minimum. Mili tary equipment formed a large part of the travelling baggage. There was no question of a separate furnishing of each temporary abode. Above all, it was necessary for the owner to be able to hold what he had. His habitation was rather a stronghold than a dwelling-house. The principal living apartment was a large hall with bare walls, open-beamed roof, narrow windows (probably unglazed) and floor paved with stone slabs or tiles. It contained very few pieces of furniture, and mostly such as could be brought by the occupants and carried away again when they went else where. Window curtains, if used, were strung on hinged rods swung away from the window in day-time. The doorway might have some similar contrivance. A large hooded chimney main tained a log fire. Metal braziers on wheels, for local heating, were added during the later middle ages. Warming-,pans were probably a still later innovation. A massive table would be fixed to the floor at one end of the hall. Upon it entertainers would mount, to divert the company between or after the courses. Long trestle tables, easily movable for dancing or displays, were in general use. The seats were mostly plain benches or stools without backs. If a fixed bench ran along one of the walls, there might be panelling at the back against the coldness of the stone behind, and a cushion or two. There were a few folding chairs, generally of metal, light and easily portable, and perhaps a chair of state. Sitting upon the floor, on cushions or rugs, was long customary. The coffer with hinged lid was the chief provision for storage. It served as a packing case during transit, and afterwards as a general repository. It also formed a supplementary bench or table. There was a simple form of dresser, for the preparation of food, with shelves above for utensils.

One or more spaces in the hall were curtained off by movable hangings, suspended from the rafters or from iron rods projecting from the walls. Separate apartments were thus temporarily pro vided. Low movable beds were placed within, covered with blankets or skins. Mattresses and pillows were stuffed with pea pods or straw; feathers did not come into general use before the I 5th century. The wealthy also had travelling beds, of palanquin form, borne behind and before by horses or men. If recesses in the hall were curtained off, a nearer approach to separate sleeping rooms was provided. The cabinets or bowers for women's work and recreation were formed in this way.

The kitchen was a low apartment with a depression in the middle of the floor for the fire, provided with a great iron grid, which was slid over for cooking upon. In some cases there were one or two private rooms, perhaps on an upper floor. Guests were accom modated in the large hall, where movable beds could be set up in case of need. Sometimes strangers had separate apartments, with an entrance from outside. In the greater houses there was a chapel, where daily prayers were read.

Later Middle Ages.

Such conditions, varied according to local circumstance, were generally prevalent in western Europe down to the close of the i 2th century. Where Eastern habits of life had already penetrated, as in Sicily or Spain, magnificent buildings were erected. A room in the palace at Palermo, Sicily, is still known as that of the Norman king, Roger II. The walls are lined with marble, and the lunettes and ceiling above are en crusted with elaborate mosaics. Changes were gradual and pro gressive, but a definite step forward was made about the 12th century. Most of the military leaders in France (and many in neighbouring lands) had by then taken part in the Crusades, and they had learned something of a more luxurious mode of living. The accumulation of possessions now began, and women took a more prominent share in the regulation of the household and the provision of daily needs. Curtains brought from the East would be of thinner texture, and they were drawn back in folds rather than swung away from the windows. The better store of hangings enabled the bareness of the walls to be relieved. The wooden ceilings were coffered, and sometimes painted in bright colours and gold. Where folding shutters were provided for the windows, the need of glazing would be obviated. The high table was placed across the end of the hall, where the floor was raised. Long mas sive tables at right angles accommodated the household and retainers. Tables of horse-shoe form might still be used, as in early times, for convenience in serving. Tables for the dishes were at the lower end of the hall. A small "credence" table, for tasting wine and liquors, was set against a side wall. Wooden cradles for infants were made to rock on the floor, or to swing between end supports. Seats with upright wood backs, and, perhaps, a carved hood above, would replace the plainer benches for the chief per sonages. The coffer, or chest with hinged lid—that perennial and indispensable article of furniture—had its drawbacks. Everything set upon it had to be removed before it could be opened. Hinged doors were therefore set in front, perhaps with a nest of drawers behind, and a long drawer below. From this the armoire and the varieties of presses and cupboards would take shape. Beds became fixtures, though not yet relegated to separate sleeping-rooms. They were of panelled wood, sometimes taking the form of a huge cup board with open front. The mattress raised above the floor was often of ample dimensions, affording space for a whole family in case of need. It was generally set in the corner of the room, and at the free angle the curtain was looped up during the daytime in a kind of rolled bundle, still exemplified in Dutch pictures as late as the i 7th century. Sometimes there was a narrow space between the bed and the wall for dressing and undressing. This was screened off by the bed-curtains.In the later middle ages the wardrobe was a separate room, with deep presses lining the walls, having cupboards above and lockers below. Here were stored the hangings, floor-coverings, curtains, tapestries and linen of the establishment, besides the garments and materials for a large household. With the lack of shops this was the place to replenish supplies. It was also the workroom of the establishment, with tables and other provision for tailors, repairers and needlewomen.

As the middle ages went forward, the hall continued to serve many purposes; but gradually the dwelling became divided into ante-chamber, hall and withdrawing-chamber. There might be also a state bedroom, where guests could be received. A lit de parade was sometimes provided solely for this purpose. The "bed of justice," of which we hear from mediaeval times onwards, was at first a couch or low seat for reclining upon, where the French sovereign met his parliament.

The kitchen was now provided with vast low arched recesses in the walls, where the fire could be better regulated than in the middle of the floor. Rotating spits, in stages, for roasting, had dripping pans below, and there were hooks for suspending cooking pots over the fire.

The floor (of stone or earthenware tiles in large houses, of the bare earth in others) was covered with sawdust, as it is even to-day in great kitchens. In course of time it became usual to spread the floor with rushes and fragrant herbs. It was not till the later middle ages that the rushes were plaited into mats. Plain woollen cloth or furs were sometimes laid down. For ceremonial, rich stuffs were spread before the royal throne. Oriental pile carpets were not used before the r 5th century, and they were rare in western Europe before the i 7th century.

Torches at first provided the principal lighting, and the fire served to give light as well as heat. There might be a few sconces fixed to the walls, with prickets for candles. A small hanging lamp with floating wick was more convenient than the candle for the light, which was usually kept burning all night within the bed curtains, as much to scare away spirits as corporeal beings. Standing candelabra of iron for many candles came into use, as well as small portable pricket candlesticks, and occasionally chandeliers or "lustres" hung from the rafters.

As the women of the household took more and more to the management of domestic affairs, furniture tended to accumulate. The use of ornaments and various articles of luxury grew during the times of the Crusades, increasing as commercial relations with the Near East became closer in subsequent centuries. Indoor provision for washing and bathing must also be included among luxuries. A long trough with a row of taps in a courtyard served for most of the household. At times there was a tank or cistern with water continually running. A metal bowl, flat-sided, was sometimes fixed to the wall of a living room, with a swinging ewer or a small cistern with tap over it, and a towel upon a hinged rod near by. Provision for reading was made by a portable lectern with sloping top. The top might revolve to facilitate reference to different books, or it would work up and down for convenience. Sometimes it had a recess for the storage of books. A sloping board for writing upon could be adjusted to the arms of a seat, or it could rest on a table. Sometimes a shallow box, with inkhole, was set on the writer's knees.

Small convex mirrors were hung to the walls as early as the i 5th century, but hand mirrors of polished metal or glass were the only mirrors in general use before that time.

An illustration in the celebrated manuscript in the Museum at Chantilly, the "tres riches Heures du Duc de Berri," represents King Rene seated at table. Behind him is a fire in a hooded chim ney. He is protected from its heat by a circular screen of plaited rushes. The wall is covered by a tapestry hung upon hooks. Rush matting is on the floor. The table is covered with a white cloth, and courtiers and servants are busy around. It forms a striking picture of seigniorial life in the first half of the isth century.

A German oak cupboard of the i sth century, carved with Gothic tracery and provided with iron hinges, is here shown in P1. I., fig. 3. An oak sideboard, from Spain, is also reproduced. (Pl. I., fig. 4.) The amount of mediaeval domestic furniture which has come down to the present day is relatively small, but the general char acteristics need to be borne in mind, for the middle ages were the cradle of later times, and much that came afterwards is explained by reference to them. Indeed, in backward countries, or in remote districts little affected by change of fashion, the mediaeval tradition has been carried down to our own times. Besides eastern Europe, parts of Switzerland and Scandinavia may be cited as examples. The wooden chair (see WOODCARVING), from Tyldalen church, in Oesterdalen, Norway, is attributed to the loth century.

Alpine Lands.

The mediaeval furniture of the lowlands was principally of oak and hard woods, but in mountainous districts, such as Switzerland, the Tyrol and south Germany, the use of fir, pine and the softer woods at hand determined the form and ornamentation of the furniture made from them. Such woods were often the only available building materials as well, and floor, walls and ceiling alike would be entirely of wood, as they often are to-day. The bedroom from the Landesfurstliche Burg at Meran, South Tyrol (Pl. I., fig. 5) is a remarkably complete and well preserved example of an interior in a house of some standing in the latter half of the 15th century. The old Swiss furnished interiors shown in Pl. I., fig. 6, though. only in one case dating back to the mediaeval period, illustrate much that has been said about earlier times. Most of them belong to a series in the Historical museum at Basle, carefully removed from old houses, chiefly in the town. There are others in the museums of Berne and Zurich, covering the period from the I 5th to the a 7th century. Floors are of wood, walls and ceilings are moulded and panelled. Sometimes there is inlay or veneering of harder and more ornamental woods. The mouldings are bold, but any carving is usually in slight relief, ow ing to the nature of the wood, and the inlay is generally simple and geometrical. Tables have legs of trestle form, and the tops are hinged so as to lift up and reveal a spacious receptacle for writing implements or articles of the toilet. Chairs are primitive, with solid wooden seats and splayed legs. Benches are fitted along the wall. Panelled beds of ample size are in the living-room. Coffers tend to be high, with a wider base containing one or two drawers. The walls being of wood, the construction of corner cupboards is simple. Flat carving may be in a style recalling fret work. Bands of foliage and other ornament following the Gothic tradition, and suited to the coarse grain and softness of the wood, are very effective. These decorative parts were painted in bright colours, and entire pieces of furniture were sometimes painted over with figure-ornament or other motives.

Italy.

The Castello d'Issogne, in the Val d'Aosta, in northern Italy, is remarkable among surviving examples of the adaptation of the mediaeval domestic interior to the mild climate south of the Alps. It was built about the year 1490 by a member of the Challant family, who held the post of governor of the Val d'Aosta. Though mediaeval in structure and appearance, it is not a strong hold, but a summer retreat. It is built in a square with a tower at each corner. There is an inner courtyard, along one side of which is a kind of vaulted portico supported by pillars and open to the courtyard. This is used as a hall, with wooden linen-fold panelling and a fixed bench running along the wall. The lunettes above the panelling are filled with fresco paintings of scenes in daily life—the shops of a provision merchant, an apothecary, and a tailor and draper, an outdoor market, and soldiers in a guard room. There is also a dining-room with credence, tables and stools, an armoury, a kitchen, servants' hall and chapel. The cof fered ceilings are carved and painted (see Plate I., figs. 9 and i o) .During the middle ages furniture in Italy differed but little from that of neighbouring countries. Any deviation was likely to be due to the use of walnut, a more tractable wood than oak, and to the outdoor life which rendered an accumulation of furniture super fluous. The Gothic style never took firm hold in Italy, though occasionally Gothic tracery is found in the furniture of Venice and Tuscany.

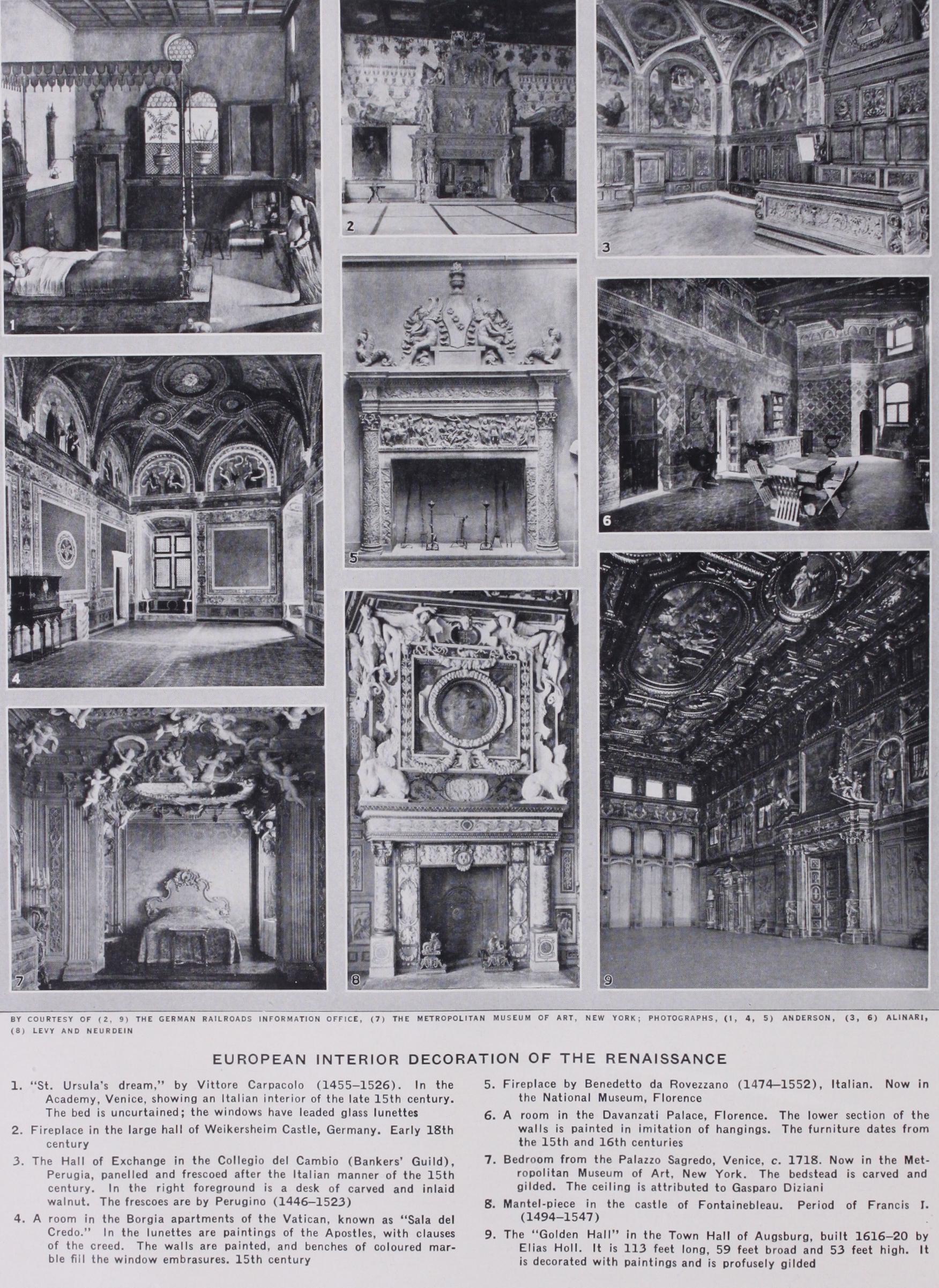

The Renaissance, which originated in Italy in the early years of the 15th century, gradually brought about a complete change in the domestic furniture of that country and of Europe. The class ical tradition had never been entirely lost in Italy. Traces of Roman greatness were to be seen in many places, though excava tion was only undertaken with the aim of obtaining building ma terials from the ancient ruins. When a deliberate return to old models was made, furniture gained an importance that it had not known hitherto. Columns, capitals, entablatures, pediments and other architectural features provided the skeleton of the structure, and the purpose of the cabinet or table, or whatever it might be, was subordinated to its form. The joiner borrowed from the architect. The furniture of the early Italian renaissance is often very restrained and beautiful. For the more elaborate kind of work, sculpture in low relief and stucco modelled in intricate patterns were much used. The stucco was usually gilt all over and picked out in colours. Such pieces became elaborate and costly works of art, though it must be admitted that they were a by product of the furniture-maker's craft. Carpaccio's painting of St. Ursula's dream, in the Academy at Venice, gives a most attrac tive idea, though in some measure fanciful and exaggerated, of an Italian interior in the last of the 15th century (Pl. II., fig. 1). The bed is of a form allied to the great panelled bed of northern Europe, but the heavy curtains are not required in a room flooded by the light and warmth of the early morning sun. There is a bench along one wall, an arm-chair, a stool and a low table. A cup board is let into the wall, and a smaller cupboard holds books and other articles. The ceiling is panelled and the windows are shut tered, with leaded glass lunettes above.

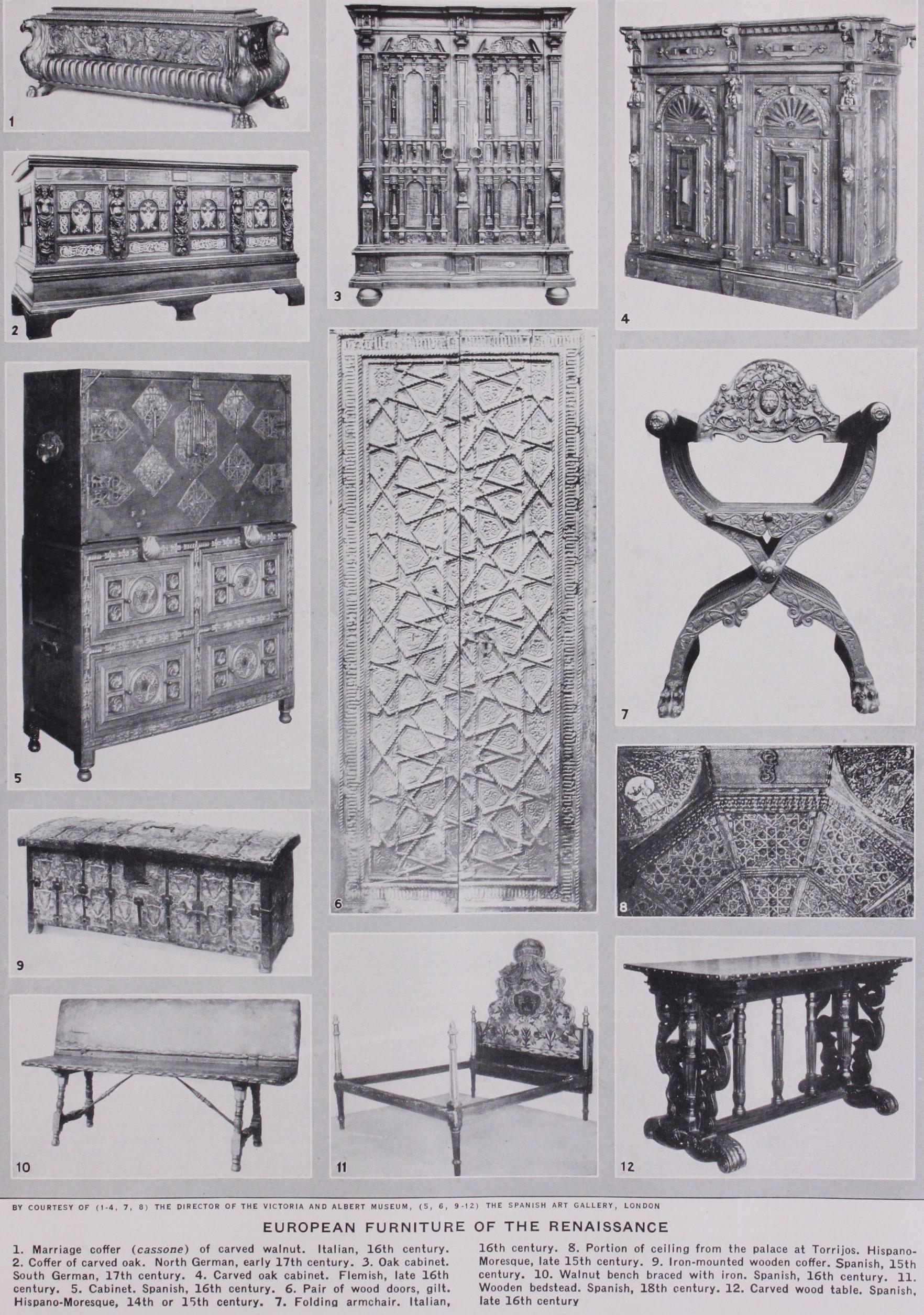

There was no class of furniture on which the wood-carver's and stucco-modeller's skill was more exercised than on the cassone or marriage-coffer, provided and filled for the bride. In addition to the elaborate relief-work and gilding, these coffers were often painted on the front and sides, and occasionally inside the lid as well, with appropriate scenes executed by some of the chief artists of the day. The cassone of the i6th century illustrated (Pl. III., fig. 1) is carved walnut. At times these chests imitate the forms of the ancient Roman stone sarcophagi. Walnut, a common wood in Italy, was an admirable material for delicate carving. The panelling of rooms was sometimes finely carved and inlaid. The Hall of Exchange at Perugia (Pl. II., fig. 3) shows the panelling, with pilasters and cornice, and a fixed bench along the wall. A large writing desk is built out into the hall. Italy did not need the heavy draperies of colder regions, and the dry climate rendered fresco-painting durable on the walls. The fixed writing desk here seen is the forerunner of the writing bureau, which became an in dispensable article of furniture as the practice of writing became general. A type of chair much favoured in Italy, and often richly carved and gilded, was evolved out of a simple joiner's contrivance of mediaeval times. The seat was a small wooden slab, generally octagonal. It was supported at front and back by two solid boards cut into an ornamental shape. Another piece of wood, in the shape of a half-opened fan, formed the back. The tables were generally oblong, supported by columns, consoles or terminal figures, with a long stretcher running from end to end.

In Italy the domestic arts were not relegated to a place inferior to those which it has been customary, since the 18th century, to designate as the "fine arts." The amazing versatility of the great artists of Italy is largely accounted for by this circumstance. The influence of the Italian furniture of the renaissance soon spread into neighbouring countries, revolutionizing the furniture making of Europe.

Austria and Germany.

Italian models were followed in the Austrian provinces to the north. The cabinet makers of Augs burg and south Germany evolved an elaborate type of work based on the example of Italy. Cabinets had doors in front, which re vealed an arrangement of drawers and compartments inside. They were covered with veneering and inlay of tinted woods, and details were delicately carved. Rooms were panelled in harmony with the furniture. The inlaid writing desk of Christoff Muller, of Augs burg, made in now in the Berlin museum, is shaped at the end like the façade of a mansion of the Renaissance. The cabinet shown (Pl. III., fig. 3) is of oak, with veneering of Hungarian oak and other woods, and mounts of tinned iron. An oak coffer, with inlay of sycamore and oak, is a representative example of north German furniture in the earlier part of the i 7th century. It bears the arms of the city of Lubeck.

France.

The French monarchs of the i6th century invited Italian artists to the court. They were employed in extensive undertakings, and the forms they introduced were generally fol lowed. Italian models in furniture were closely imitated. The carved walnut furniture of France in the i6th century is remark able for gracefulness and delicacy. Sometimes it is relieved with inlay of small plaques of figured marbles and semi-precious stones. Elaborately-carved oblong tables were supported by consoles or fluted columns, connected by a stretcher surmounted by an arched colonnade. Cabinets and chairs followed Italian shapes. As in other countries where a tradition has been imported from outside, the influence was largely restricted to the capital and to districts under the influence of the court. Older local traditions lingered in the remoter regions. In France, for example, the distinctive furni ture of Brittany and Normandy has retained its local characteris tics down to the present day.

Spain.

In Spain the alien influence came at an earlier time and from remoter parts. With the invasion and occupation of the south by Arabs and North Africans, in the 8th century, the greater part of the peninsula became virtually an oriental country, and so it remained for seven centuries. After the expulsion of the last Arab ruler, at the end of the r sth century, many "Moriscos" still remained in the country, and the intelligent and industrious craftsmen among them still worked for the Christian rulers of the land in their own traditional styles. The vaulted, coffered ceiling in pine wood, elaborately carved and painted (Plate III, fig. 8), comes from the palace at Torrijos, near Toledo. It was built at the end of the isth century for Gutierraz and his wife. Several types of these oriental panelled or coffered wood ceilings are found in Spain. The fine pair of carved and gilt wood doors reproduced (Plate III., fig. 6) recalls the Saracenic work of Egypt, but, nevertheless, it is typical of southern Spain in the i4th century. The Latin inscription in Gothic lettering will be noticed. A type of cabinet known as the vargueno is typically a Spanish production—a medley of European and oriental elements. The upper part is a chest, generally elaborately mounted in wrought iron, with a massive iron lock to the drop-front. When the front is lowered, an elaborate arrangement of drawers and recesses is revealed, often with ivory inlay, gilding and brilliant colouring. Sometimes the base is another chest with cupboards. Later ex amples have supports with baluster legs and arcading elaborated from French or Italian models. The chest itself is sometimes decorated under the same influence. Mediaeval Spanish furni ture has various foreign elements. The buffet already referred to recalls French work. The iron-mounted coffer, originally painted all over, and bearing shields of arms is a Spanish adapta tion of the Italian cassone. Folding chairs of X-shape, with mosaic inlay of ivory and coloured woods, were much in use in the i6th century. There is a tendency for Italian models to be followed in the furniture of the i6th and z 7th centuries. In a country so re nowned for its iron-workers, it is not surprising to see that bracing irons of fanciful workmanship are often attached for strength to tables and benches. A Catalan bedstead of the r 8th century with painted back is reproduced.

Low Countries.

Perhaps the Italian renaissance found its most characteristic expression outside Italy in the Low Countries. The Gothic furniture of earlier times was solid and strong, with linen-fold pattern and intricate tracery. Its use is exemplified in the work of the contemporary oil painters, whose work gives so convincing a picture of the prosperous and comfortable domestic life of those industrious provinces in the middle ages. Rooms were lofty and spacious. The walls were wainscoted in oak or covered with embossed and painted leather. Windows were partly enclosed by glass panes, often embellished with heraldic and figure orna ment, and partly by inside shutters of oak, studded with nails. When the shutters were thrown back, light and air were provided at the same time, for numerous Dutch pictures show that in many cases there was no glass behind them. Chimney pieces, with over mantels carried up to the ceiling, were embellished with marble columns and elaborate carving, and similar architectural orna ment flanked the doorways. Heavy oak tables (sometimes "draw tables," which could be extended to twice the length) had mas sive bulbous legs and solid stretchers. The beds in the corners of the living rooms were heavily draped. Folding wooden -chairs and low stools with more or less elaborate turnery, were still used, besides a new type with baluster formed or twisted legs, arms, and straight backs heightening as the i 7th century went forward. The leather upholstery of seat and back were replaced by caning in the latter half of the century, when the high back had a narrow panel flanked by balusters or columns resembling the legs. Low chairs with back, arms and ears in one solid piece, were stuffed and padded, and upholstered with tapestry, embroidery, velvet or other material, showing that the limit of domestic comfort had by that time been reached. Large folding screens with leather panels, or others of lacquer-work imported from the East, kept out the draught. Lacquered furniture was also imported from China and Japan, and travellers learned the secret of this specifi cally oriental craft, so that imitations were made in Holland, as well as in France, north Italy and elsewhere. The great tapestries for which the Netherlands had long been famous afforded addi tional protection from the cold air, and oriental pile carpets were used as tablecloths, for it was not yet customary to spread them on the floor, where they would have accorded ill with the habits of domestic life.

Scandinavia.

In Scandinavian countries much domestic architecture continued to be of wood, and the furniture remained simple and primitive. Relief was afforded by painted linen hang ings, sometimes representing biblical scenes, with the figures in contemporary peasant costume, and by brightly-coloured cushions in embroidery or tapestry. Houses of the well-to-do contained furniture from north Germany or the Low Countries, providing models which the local might copy.

The Baroque.

During the r 7th century the baroque (see BAROQUE ART), had a drastic effect upon furniture design. Large wardrobes and cupboards had twisted columns, broken pediments and heavy mouldings. The Venetian chair of the later years of the i 7th century, reproduced (Pl. IV., fig. I), is an admirable illustra tion of the tendencies of the time. It is of carved walnut, uphol stered in red velvet.The baroque style owed much to the oriental influence which swept over Europe in the i 7th century, when several of the European maritime countries established regular trading relations by sea with India and the Far East. Besides the furniture and domestic goods imported from the East, the oriental craftsmen worked, for export, in a pseudo-European style, from designs supplied by the traders. Heavy tropical woods were also brought to Europe, and from these furniture was made which borrowed much from the prevailing taste for oriental elaboration. Ebony cabinets with waved mouldings, intricate carvings in low relief, and profuse inlay in tinted ivory and coloured woods, were made in Italy, Germany and the Low Countries. The ebeniste then acquired his name. A Dutch cabinet of the 17th century, in carved ebony, inlaid in ivory and coloured woods, is illustrated (Pl. IV., fig. 2) .

Later French.

In France, the Italian influence of the i6th century was gradually assimilated, and a national style of furnish ing was evolved which soon spread its influence into neighbouring countries. The "styles" of Louis XIV., the Regency, Louis XV., Louis XVI., the Empire and so forth, have passed into the phrase ology of Europe generally, and their influence has operated where ever the terms have been used.The reign of Louis XIII., covering most of the first half of the century, was a time of transition. The fame of his son and successor, Louis XIV., the great monarch, might suggest that the outlook of a great nation was then modified and enlarged by the force of a single personality, but it was the national spirit which created Louis XIV., and his times. Expansion in Asia and America, and the growth in the national wealth, were the causes which led to the building of Versailles and the Galerie d'Apollon of the Louvre. The great "Salon" now came into being, and the number of separate apartments was multiplied. A suite would comprise a vestibule, ante-chamber, dining-room, salon, state bedroom, study and gallery. Stately and spacious staircases were provided. The interior economy of the modern house dates back to this time.

The Gobelins factory, which still remains a national establish ment, was founded under Louis XIV. for the production of meu bles de luxe and furnishings for the royal palaces and the national buildings. Charles Le Brun was appointed the first director of the Gobelins. Furniture was veneered with tortoiseshell or foreign woods, inlaid with brass and ivory, or heavily gilt all over. At times it was even completely overlaid with silver. The name of Andre Charles Boulle (q.v.) is particularly associated with this tendency. His cabinets and tables were completely covered by sheets of tortoiseshell and brass cut into intricate patterns so as to fit into one another, the tortoiseshell alternately forming the pat tern and the ground. (See INLAYING.) The light fanciful "gro tesques" of Berain were much used 'f or this work. Heavy gilt bronze mounts protected the corners and other parts from friction and rough handling. An example of this work, of a later period, in the Wallace collection, London, is shown in Plate IV., fig. 3. In ancient times, folding chairs might be of iron or bronze, and iron hinges and mountings have, of course, been used at all times where strength was required. The massiveness and elaboration of the furniture under Louis XIV. was followed by the rococo style of the regency in the first half of the 18th century. This style owes more to the influence of Chinese art than any other. The famous writing-table of Louis XV. (P1. IV., fig. 4), exhibited in the Louvre, was the work of the celebrated furniture makers, Riesener and Oeben. It is said to have taken nine years to make. Furniture under Louis XVI. showed some return to classical models. Curved surfaces were replaced by severer design,' and straight, tapering legs succeeded the cabriole. A limit of elegance unknown before was reached. Plaques of the delicate porcelain of Sevres, with ornament painted in brilliant colours on a dazzling white ground, were freely employed upon tables and cabinets (see Pl. IV., fig. 5). The gracefultapestries of the Gobelins and Beauvais replaced the heavy velvets of the 17th and early 18th centuries for upholstering chairs and settees and for window hangings. The bedstead shown (Pl. IV., fig. 6) is of carved and gilt wood, with coverings and canopy of pale blue silk. The French furniture of the 18th century set the standard of elegance and refinement for the whole of Europe.

Rooms were rebuilt or remodelled in accordance with the taste of the day. Elaborate parquet flooring was introduced before the close of the 17th century. Walls were enriched with relief work and gilding. Tall glass mirrors, reaching from floor to cornice, were set between the windows and protected by console tables. Ceilings were painted by some of the chief masters of the time. Later, when more restrained types of furniture were made, walls were painted white, with mouldings picked out in gold. The plain whitewashed ceiling did not come into favour before the 18th century was well advanced.

Two French domestic interiors here reproduced are separated by a century of time, but the contrast is greater than that involved in this circumstance. The earlier is provincial work, and it differs materially from the work then being done for the court of Louis XIV. The other is from Paris, showing in a marked degree the refinement and delicate workmanship of the period of Louis XVI. The panelled room from the Château de la Tournerie, near Alen con (Pl. IV., fig. 7), is of oak, painted and gilt, and embellished with embossed leather panels enriched with painting and gilding. The château dates mainly from the 16th century, but the panelling was erected between the years 1682 and 1694 by Alexandre Sevin. It bears his crest and initials with those of his wife. The boudoir (Pl. IV., fig. 9) is from a house in the rue Vieille du Temple, in Paris. The room is said to have been erected under the personal supervision of Queen Marie Antoinette and Madame de Serilly, her friend and lady of honour.

Later

the end of the 18th century the influ ence of the discoveries that had been going on at Pompeii pene trated into Germany and Austria, and interiors were decorated in the light and fanciful style exemplified in the wall-frescoes of the Pompeian houses. About this time a vogue arose for draping interiors into the resemblance of a tent. The draperies completely covering the walls were sometimes pleated, and if the ceiling was high enough it would be concealed by a kind of sloping velarium. A bed would be enclosed by festoons of drapery.The influence of the well known cabinet-makers of England in the second half of the 18th century, was reflected in the work of the furniture-makers of north Germany and Denmark.

The Napoleonic regime hastened the changes then in progress in European furniture-making. The example of Roman majesty was continually in the emperor's mind, and the "Empire" style aped the uninspired decorative formalities of Roman imperial times. Furniture with outcurving legs was copied from representa tions in Roman reliefs. Griffins and sphinxes were freely used as decorative motives or supports. Beds with rolled ends and stuffed backs, sometimes with drapery above like a gable roof, were the forerunners of the sofa of the later years of the century. The rest of Europe adopted the "Empire" style, of which the chief merit was a return to more sober models after the exaggerated fanci fulness of previous styles.

Towards 1825 the reaction came. Earlier fashions were again reverted to, for a time, in a half-hearted manner. The new wealth of industrial and trading communities gave rise to new ideas of material well-being. The comfortable "Biedermeier" style arose in Germany. Furniture was luxuriously cushioned and padded Thick curtains, festooned draperies, table-covers, antimacassars, tassels and fringes were seen everywhere. The time when these began to be curtailed or to fall into disuse is within the memory of the older generation to-day.

The subsequent tendency to revert to imitations of the furniture of the 17th and 18th centuries is not altogether praiseworthy. It is easier to stifle originality than to revive it when the inevitable need arises. Moreover, there were contributory causes for most of the changes which have been here briefly reviewed, and to copy a type of chair or table when the circumstances which originally gave rise to it are no longer operative is not in harmony with the soundest principles. (See also the various short articles on pieces of furniture, such as BED, CHAIR, CHEST, TABLE, etc.; also the different styles and periods, such as Rococo, BAROQUE, etc.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-Viollet-le-duc,

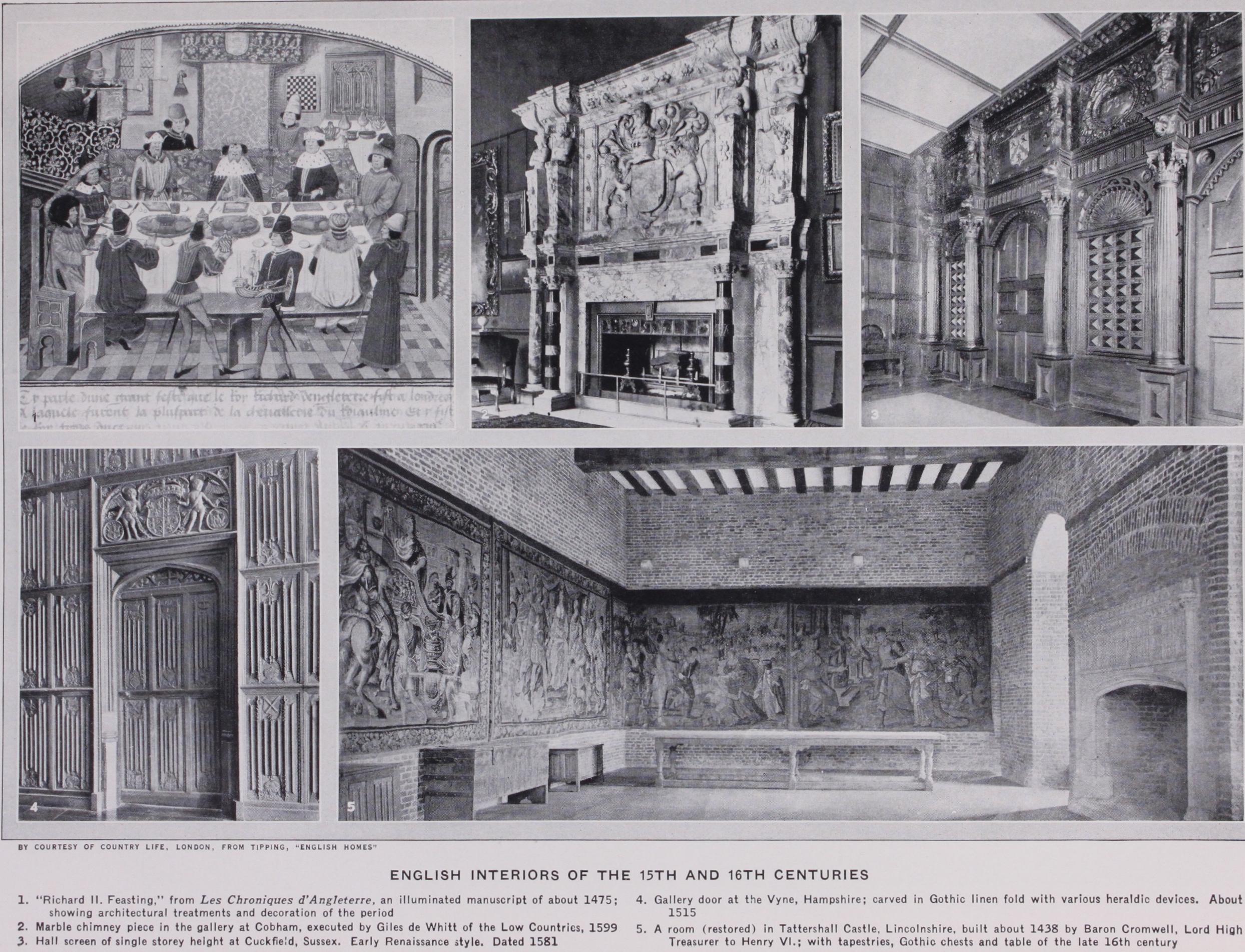

Dictionnaire du Mobilier f rancais Bibliography.-Viollet-le-duc, Dictionnaire du Mobilier f rancais (1858) ; H. Havard, Dictionnaire de l'Ameublement (1887-9o) ; Interi eurs d'Appartements, Châteaux, Eglises, etc., Guerinet edit. (1904) ; E. Maillard, Old French Furniture and it Surroundings (1925) ; Lady Dilke, French Furniture and Decoration (19o1) ; A. Byne and M. Stap ley, Spanish Interiors and Furniture (1921-25) ; A. Pedrini, L'Ambiente, it Mobilio e le Decorazioni del rinascimento in Italics (1925) ; W. Von Bode, Italienische Mobel (1902) ; G. L. Hunter, Italian Furniture and Interiors (1917-19) ; P. Wytsman, Interieurs et mobiliers anciens (1898-1902) ; K. Sluyterman. In,terieurs anciens en Belgique (1913) ; E. Singleton, Dutch and Flemish Furniture (1907) ; T. K. Yerbury, Old Domestic Architecture of Holland (1924) ; C. H. Baer, Deutsche Wohn und Festraume (1912) ; H. Schmitz and H. P. Shapland, Encyclopaedia of Furniture (A. F. K.) Henry notable early specialist in house decoration in England was Henry III., who gave us Westminster Abbey. The Liberate Rolls of his reign preserve for us all the orders he gave for the adornment of his various castles and manor houses. Larger windows, and, especially, rose windows were built in halls, their painted glass adding to the rich colour decoration that the king loved and obtained at other times by painting "histories" on his walls, as in his Great Chamber at Westminster. His queen had a figure of winter painted over her fire-place there, and spring-like flowers painted on the white-wash of her room at the Tower. Walls were frescoed with histories, including scenes both biblical and classic, and below them often was wainscoting with painted and decorated boarding. Wrought roofs or painted ceil ings completed a rich domestic treatment, which was very rare in 13th century England, when walls were bare and hangings were the usual means of decoration resorted to by nobles or rich burghers.Flanders tapestries, known by the generic name of "arras," were the most favoured material. Solidly woven, they resisted the wear and tear of the movings of great men who had various estates but little gear. Tapestries were hung curtain-wise from wood-quartering set with tenterhooks, and such have recently been renovated at Tattershall castle, where, except for such hang ings, the brick structure of the walls was visible, as is seen also in a picture from an illuminated manuscript produced in Flanders for Edward IV. (c. 1475) of Richard II. feasting (Pl. V., fig. 1). There is no arras, but the king sits under a rich textile canopy, similar material also hanging in front of the musicians' stand. It was not as yet customary to have walls lined with oak, but it was used, and used richly, by the highly expert carpenters of the day for such structural purposes as hall screens and room parti tions. They had not, however, taken in hand the chimney-piece, which remained in the domain of the mason who in the 15th century bestowed pains upon its adornment, as we see in the great heraldically carved chimney-pieces at Tattershall, dating from about 1438.

The Development of Panels.—It was not, however, until the days of Elizabeth that this feature became monumental, often reaching from floor to ceiling by the use of superposed classic columns. By that time framed wood linings had become usual, and to them gradually became applied the word "wainscote," which had originally merely meant foreign oak. Such panelling, although only common under Elizabeth, occurred under Henry VIII., the finest and amplest surviving example being probably that in the Gallery of the Vyne, in Hampshire, where the linen fold carving is enriched by various heraldic badges that enable us to date it from between 1515, when Wolsey was made a cardinal, and 153o, when Catherine of Aragon fell into disfavour (Pl. V., fig. 4).

The same treatment, extending also to ceiling beams and panels, we may still see in such Essex houses as Paycocke's, in Cogges hall, the Granby inn at Colchester or the manor house at Tolleshunt Darcy.

Frescoing walls still continued, but most of it has perished. Some late 15th century representations of Bible scenes have recently been found under whitewash at Cothay, in Somerset, while of Elizabeth's reign a very good example has come to light at the White Swan inn at Stratford-on-Avon, depicting scenes from the story of Tobit.

Hangings, however, still held the premier place as wall cover ings. In the early part of the 16th century, the number of sets belonging to kings and great men was almost countless, and a Vyne inventory of 1 S41 gives sets in almost every room of the house, including the chambers of dependents. A somewhat simi lar effect was reached by cheaper means, and there was a great output of tempera—painted or "stained" cloths, using the same subjects as tapestry—histories from biblical or classic sources, verdure of woods and fields with beasts and birds and decorative subjects passing from Gothic to Renaissance motifs. Nearly all this "counterfeit arras" has perished, but a set displaying the Acts of the Apostles survives at Hardwick hall in Derbyshire.

Leather, embossed, painted and gilt, was less used in England than on the Continent, but such woven fabrics as velvets and damasks for the wealthy, and "sayes and bayes" for modest folk, found a place on the walls as well as for bed and window hangings.

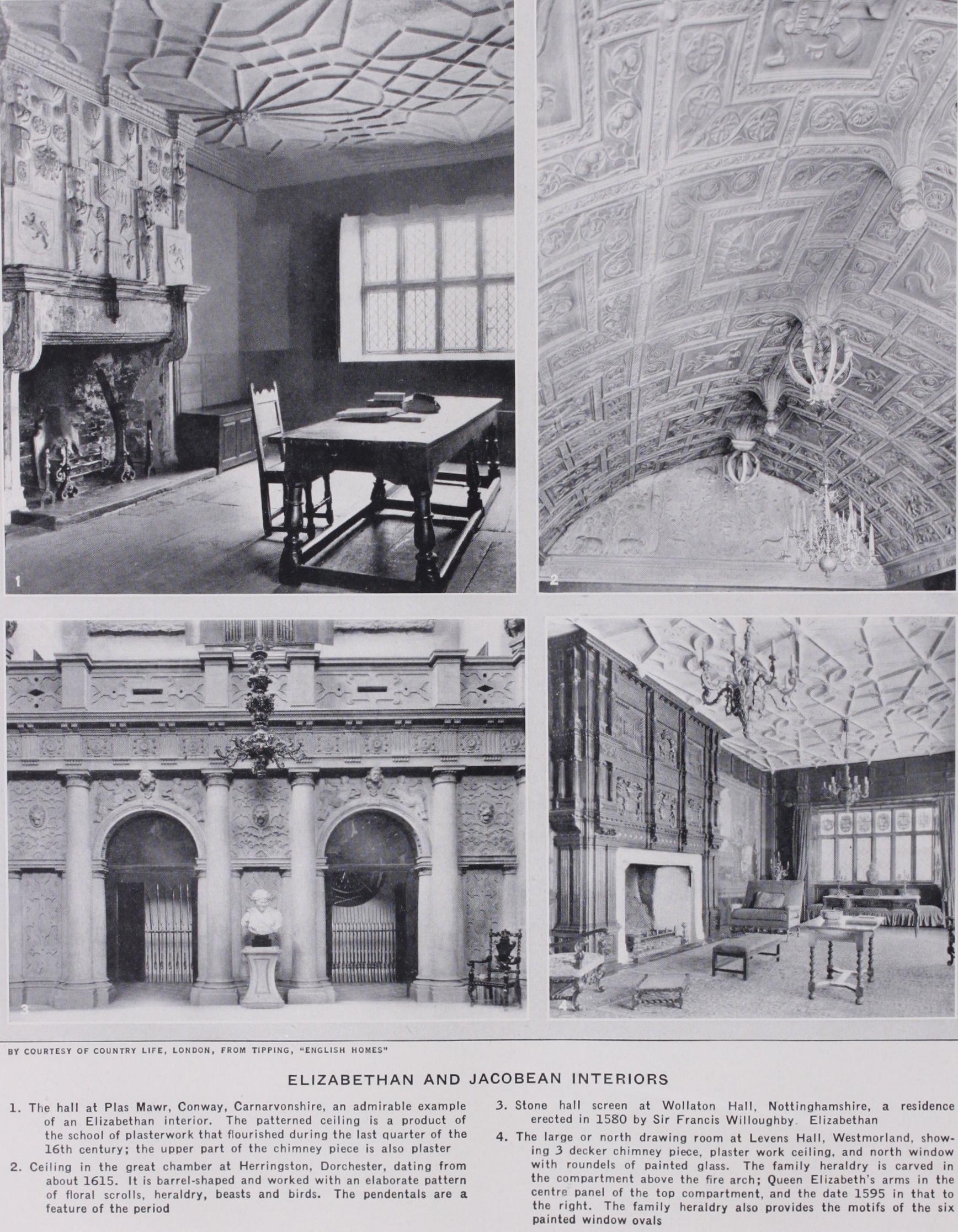

The Elizabethan joiner, when his employer's purse per mitted, enriched his wainscotings with carvings and inlay and completed the circuit of the room with elaborate oak door-cases and chimney-pieces, using for them classic orders and Renaissance motifs. For the most part their work shows an uncultured vivac ity rather than a trained head and hand, a knowledge of the anatomy of the human form being very rarely displayed. Typical of the English craftsmen of the day is the great drawing-room at Levens in Westmorland. The chimney-piece, dated 1595 (Pl. VI., fig. 4), is of three-storeys, Doric, Ionic and Corinthian orders being piled one upon the other. Elaborately framed wainscotings, enriched door-cases, plaster-work ceiling and roundels of painted glass in the windows complete the picture.

Screens continued to be used in halls even when they were of single-storey height, as at Cuckfield in Sussex, dated 1581 (fig. 5). The vast majority were of oak, but in important houses, stone was sometimes used, as at Wollaston (Pl. VI., fig. 3) and Montacute. Stone and even marble were used for chimney-pieces, especially in James I.'s reign when Max. Colt, "carver in wood and stone of all his majesty's works," provided three marble chimney pieces for Hatfield ; and we find similar ones at Knole and Brams hill. One example, however, there is of the previous reign ; a noble chimney-piece in the Gallery at Cobham, wrought in by Giles de Whitt (Pl. V., fig. 2).

Plaster Ceilings.—Although wainscotings became the normal wall treatment under Elizabeth and her immediate successors, yet there was still scope for tapestry, and also for enriched plaster ceilings consisting of narrow interlaced ribs forming geometrical patterns. There are interesting examples at Plas Mawr in Con way, where the same material forms the upper part of chimney pieces, the royal arms indicating a date in Elizabeth's reign (Pl. VI., fig. 1). Such treatment of ceilings was often very elaborate in those distinctive Elizabethan rooms, the long gallery and the great chamber, which were often upstairs ; and greater height was obtained by using the roof space and forming a barrel-shaped ceiling. They exhibited not only the narrow ribbing of Elizabeth's time, but also the broad bands with enriched soffits that came in under James I., one of the finest examples of which is at Her ringston, near Dorchester, dating from about 1615 (Pl. VI., fig. 2).

The Staircase also reached its final development in this reign. In mediaeval times, the winding newel form, sometimes of wood but more often of stone and never very wide or easy in gradient, had prevailed. But under Elizabeth it had begun to be placed round an ampler open space, and its decorative possibilities being recognized, enriched newel posts, balusters and strings were given to it. The idea was developed under her successor, and one of the finest, both in planning and execution, is the great stair at Hatfield, dating from 1610. The newel posts are richly carved and surmounted with figures so skilfully sculptured in wood that they may well be the work of Colt himself. Here, and at Audley End, the halls, which still rise to the roof, are fitted with great screens embodying all that is best and finest of the native design and workmanship of the time.

Jones and Webb.—A feeling for classic reserve was now spreading and the Late Renaissance period might well have begun under Charles I. but for the political difficulties that checked the zest for fine building. Returning from Italy in 1615, Inigo Jones introduced the new style in the Whitehall banqueting house and the Queen's house at Greenwich, and, despite English conservatism at first and the Civil War and the Commonwealth afterwards, we find his hand and that of his kinsman and associ ate, John Webb, at Wilton, Forde abbey and Thorpe, all houses altered or built by men on the winning, or Parliamentary, side. Also built under the Commonwealth is Coleshill, the earliest and one of the best of English country seats where classic form and Italian tendencies prevail.

Wood was less used than stone and stucco by the Italians for wall linings, and Inigo Jones favoured their materials as well as their manner. Webb, however, and other Englishmen were more northern in taste and native in training, so that wood held its own in England till the end of the century. But it had to conform to the new taste. Wainscotings must no longer be framed sheets of small panels in the nature of movable linings, but must simu late wall structure. They become architecture, not furniture. Vast panels thrust forward from their stiles by bolection mould ings are made up of two or more boards skilfully chosen and worked to hide the joint, even where they are left unpainted, as by Grinling Gibbons, the amazing delicacy of whose carving in lime is obscured by paint but stands out excellently against an oak background.

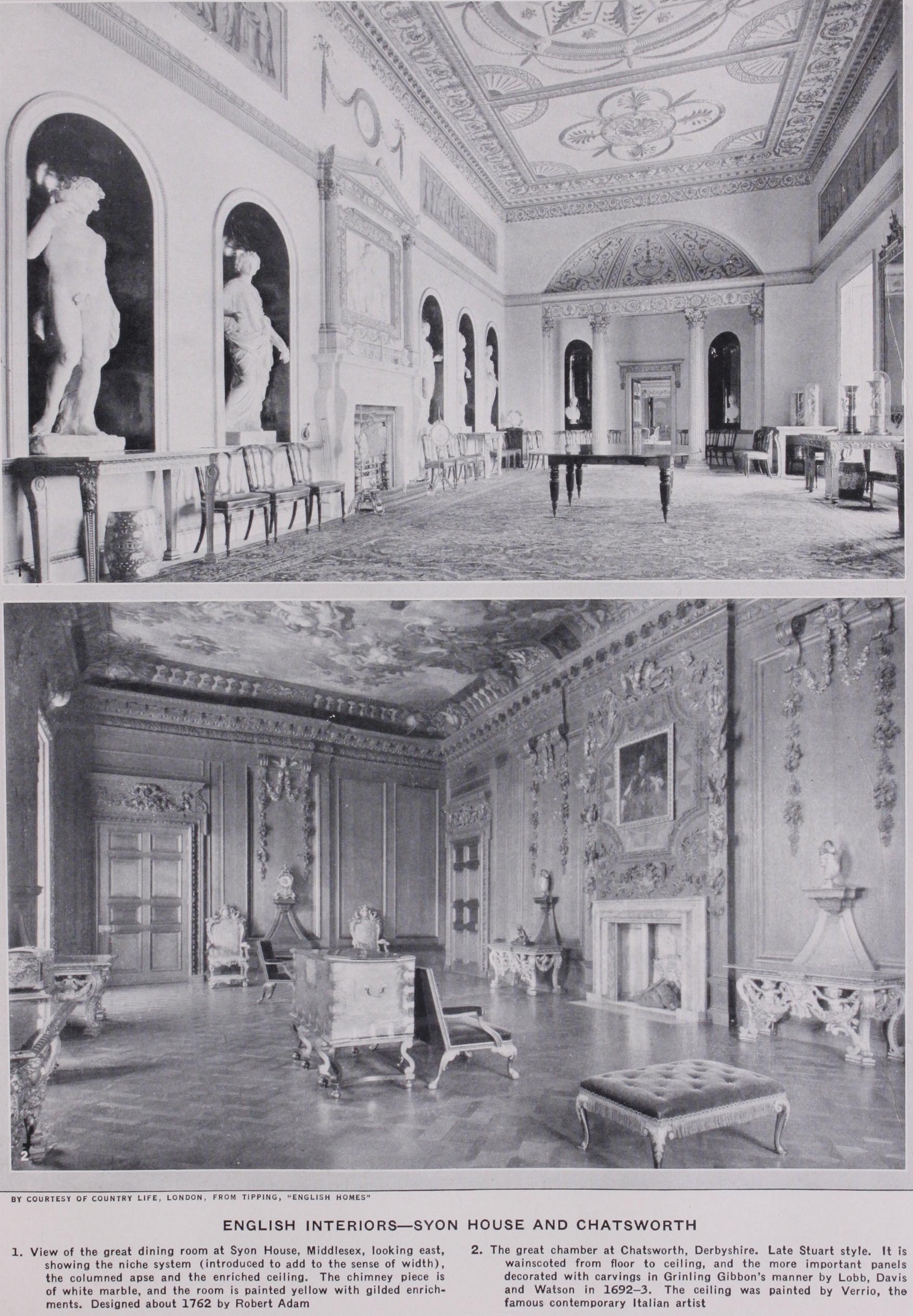

The Age of Wren is characterized by an architectural treat ment as of stone but with the natural surface showing, as ex emplified by the admirably designed and executed joinery not only in churches and public buildings, but in houses, such as Belton and Chatsworth (Pl. VII., fig. 2). The passage from the early to the late Renaissance period is a change not only of style but of spirit. During the former, the craftsmen retained much of the independence of action of mediaeval times, and the work was free and forceful but not fine. But perfection, reached through discipline, is the essence of the classic spirit. The design be comes more learned and includes detail which it was the business of the executant to follow obediently but skilfully. The field of individuality was closing for the craftsman, but that of dex terity was opening wide. Thus mastery of technique is a dis tinguishing feature of men like Gibbons and Hopson, Strong and Ti j ou,—natives and foreigners who combined to give finish to the decorative output of the later Stuarts.

The

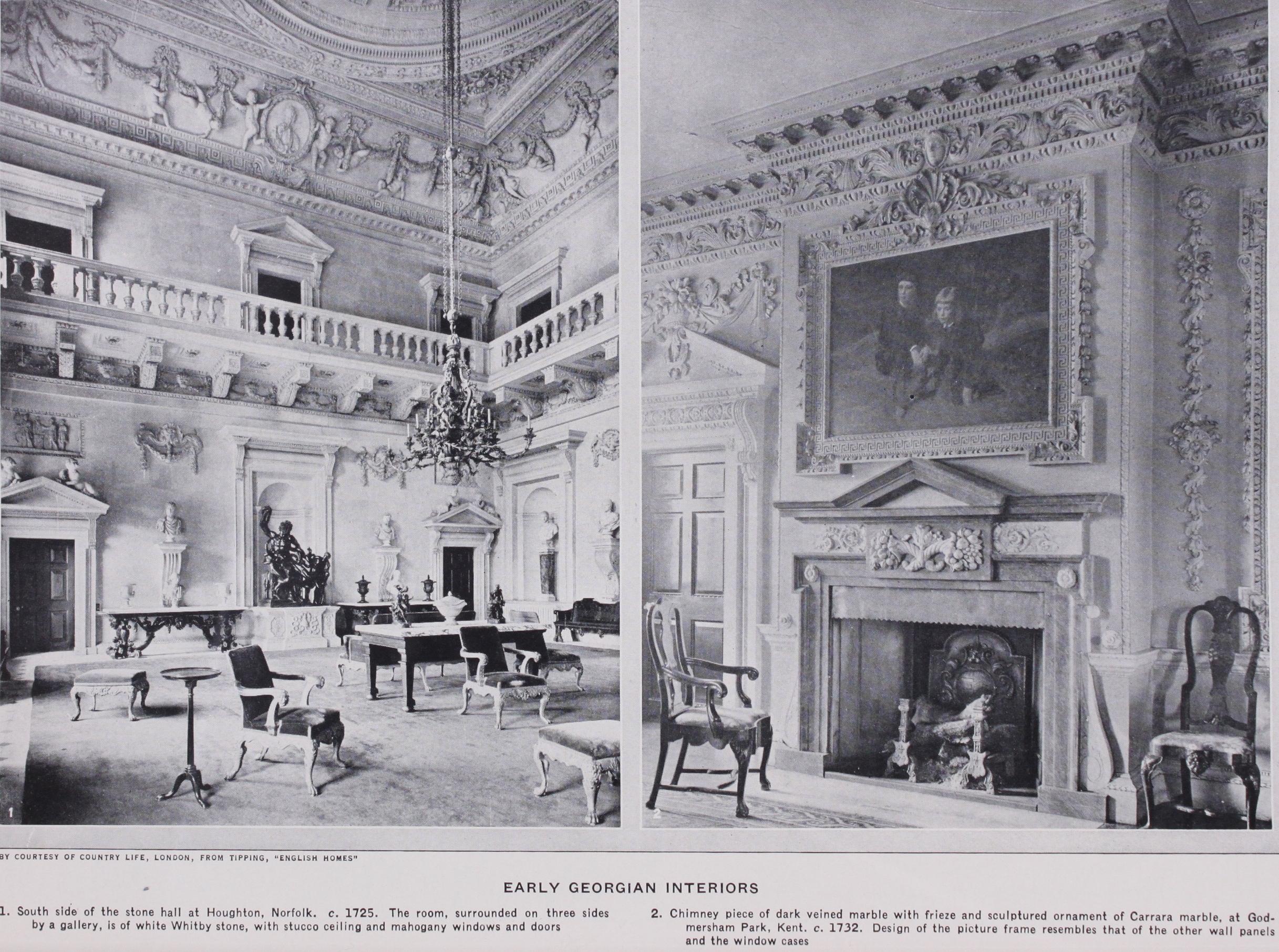

Georges.—Even during the last years of that dynasty, and still more under the Georges, the wood-workers found their domain contracting. Italy exerted more and more influence, stone and stucco became more used. Vanbrugh began and the Burlingtonian school continued the stucco, stone or marble halls of the new Whig palaces, such as Castle Howard and Blenheim under Anne, Houghton and Holkham under George II., Syon and Heveningham under George III. Stone treads and iron balustrad ing, moreover, were introduced for staircases, although in this feature the joiner long retained the lead. Under Charles II. the work is solid with massive balusters or open panels elaborately carved under a broad hand-rail, as at Wolseley or Sudbury. But with the 18th century it becomes lighter and more delicate, although equally finished and rich, as at Beningbrough in York shire where, in 1716, we find the joiner still supreme, and are en chanted with the quality and quantity of the wood-work as it appears there and in so many doorways and chimney-pieces, shutterings and framings in George II. houses, like Godmersham in Kent (Pl. VIII., fig. 2).Elsewhere, however, it is the Italian stuccoist who holds sway and riots in the exuberant ornament that was so wonderfully reached by experts in it stuc, and of which we find outstanding examples at Mereworth and Houghton (Pl. VIII., fig. I), Moor Park and Clandon.

Textiles.—But it was not only stone and plaster that was driving the joiner from walls of rooms. Textiles became in creasingly popular. For them as for wood the late Renaissance demanded a more architectural handling and they were no longer hung but stretched on frames fixed above a dado. Not only tapestry but cut velvets and damasks were favoured, and a single order for these given by the duchess of Marlborough in 1 7 07 was for over 3,00o yards. Indian calicos and other lighter and less expensive textiles were also fashionable, but the most serious, because still cheaper, competitor to wainscoting was paper, which, from being a 17th century rarity became a preva lent feature as the 18th century progressed. During George III.'s reign we notice an increasing lapse from classic restraint and Palladian purity. French rococo joined Italian baroque and was sprinkled with vagaries that passed for Chinese and Gothic. Ceilings, chimney-pieces, door-cases were apt to be so treated, the most astonishing being perhaps those at Clayden in Bucking hamshke.

Adam.

Reserve rather than excess, however, was the English characteristic, so that baroque and rococo gave way to the choice delicacy and clean lines that were the basis of the style of Robert Adam, who commenced his London practice in 1759. With him the despotism of the architect over the craftsman was complete. No detail of decoration or furnishing escaped him : his rapid and precise draughtsmanship covered the whole ground. The executant must not depart one hairbreadth from the drawing supplied, but he must have reached exquisiteness of technique. This spirit, joined to that of severity and restraint in design, makes the per fection reached during the last decade of the 18th century a little chilling and inanimate, implying a ceremonious rather than a domestic life.Adam's clients, however, were for the most part the Italy loving leaders of an aristocratic and artificial age, who affected a palatial and ultra-architectural treatment of interiors, as shown by the painted wall surfaces broken by pedimented door-cases, the columned apses and the scooped-out niches that we find in the hall at Kedleston, the dining-room at Syon (P1. VII., fig. I) and the saloon at Heveningham. In smaller and more domestic rooms, if the materials differed, the same practice obtained. Even carpets were made to reflect the ceiling design. Wood was never left unpainted, and although the joinery is still admirable, the en richment is often in composition or in pewter. We find specially designed temple-fronted bookcases, and specially painted pictures set in specially designed frames fixed and painted to form an integral part of the wall structure.

"Gothic."—So much logical completeness, such wholly un emotional perfection, was bound to stir up opposition, especially at a time when a new romantic school was forming and the cult of the picturesque was gathering strength. Although architecture and decoration—indeed, life itself—were treated much as play things by Horace Walpole, and Strawberry Hill was a mere con fectioner's romance, yet his influence was large and helped to turn James Wyatt from the classic manner, which he had prac tised as successfully as Adam, to pseudo-Gothic. For decoration it was a singularly unfortunate introduction. What in the mediaeval interior was not movable was truly structural, and not imitative of it ; so that not only did flimsy wood, plaster and paper decora tions entirely miss the Gothic spirit, but they were introduced as the trappings of houses designed to meet entirely different habits of life. Thus, when the 19th century was reached, a plan that, in the disposition of parts, the shape of rooms, the height of ceilings, suited the habits and views of the day, might be decked out by the architect in what he was pleased to think was Gothic or Tudor, Roman or Greek, French or Italian, Egyptian or Indian.

The last half-century has been largely a struggle to get free from this welter of confused aims and misunderstood styles, but with all this there is too great a reliance on the past, on the halcyon days of the Renaissance styles, early and late. The best craftsmen are employed on mere copying, on the production of "Period rooms," so that among decorative styles we cannot in clude one of to-day.

See ARCHITECTURE; LAMP; LIGHTING AND ARTIFICIAL ILLUMI NATION ; METAL WORK ; RUGS AND CARPETS ; TAPESTRY ; TEXTILES.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-Sir R. Blomfield, History of Renaissance ArchitecBibliography.-Sir R. Blomfield, History of Renaissance Architec- ture in England, 1500-1800 (1897) ; J. A. Gotch, Early Renaissance Architecture in England (1914) ; H. A. Tipping, Grinling Gibbons and the Woodwork of his Age, 1648-172o (1914), and English Homes, 1066-1820 (1920-28) ; A. Bolton, The Architecture of Robert and James Adam, 1758-1794 (1922) ; M. Jourdain, English Decoration and Furniture, 176o-182o (1922), and English Decoration and Furniture, 1500-1650 (1926) ; L. Turner, Decorative Plasterwork in Great Britain (1927). (A. TI.)