Paints and Varnishes Wood Finishes

WOOD FINISHES, PAINTS AND VARNISHES Wood, which is both the most available and the most easily workable of structural materials in the majority of the habitable regions of the globe, has from the earliest times been extensively utilized. When, in the course of cultural development, the sense for beauty was awakened, the art of wood finishing had its begin ning. In ancient Egypt the embellishment of wood structures by painting and gilding reached a comparatively high state of develop ment, and it was diffused thence, slowly, eastward and westward throughout the settled regions of the world. Each country re ceiving the tradition, modified and adapted it in conformity with the nature of the native woods, the materials available and the cultural genius of its people.

In the Far East, and especially in China, a highly specialized art developed under the early dynasties, and was carried thence to Japan where it reached its highest state of development. The treatment familiar on Chinese and Japanese articles of vertu and known as lacquer is based on the sap of a tree extensively culti vated in both countries solely for this use, the Rhus vernici f era, which is closely related to the Rhus toxicodendron of the West, and similarly poisonous. Various grades of lacquer or varnish are made by treatment and selection of its sap or juice, and the lacquer, col oured with selected dyes or pigments is applied in successive coats (in the finer pieces as many as 16) each laboriously ground down with emery flour or other abrasives and as laboriously polished with different substances, the final polish being given with pulverized deer's horn. Each coat must be dried in the dark and in a moist atmosphere. Inlay work and other decorative materials are ap plied to the lacquer while it is still moist and imbedded therein by the application of subsequent coats.

In Europe during the middle ages and later, besides gilding and similar processes, the decoration of wood consisted principally in staining with a vegetable dye, such as a decoction of log wood, or a chemical agent, such as tannic acid, and the subsequent ap plication of a drying oil or a spirit varnish, consisting of a gum resin (sandarach elemi, damar, etc.) dissolved in a volatile solvent, or East Indian lac dissolved in alcohol. Wax was also a favourite material for finishing such work.

The French artisans early developed a finishing process of unique quality which is still popular under the name "French Polish." The process is simple though somewhat tedious. After the surface has been properly prepared a very dilute solution of shellac in alcohol is applied with a pad made of stocking material. As soon as this coat is dry another is applied over it. This is re peated until the required lustre is obtained. Then, using the same pad, the surface is polished with a very little linseed oil, and after standing over night the polishing with oil is repeated. The soft sheen obtained in this way cannot be duplicated.

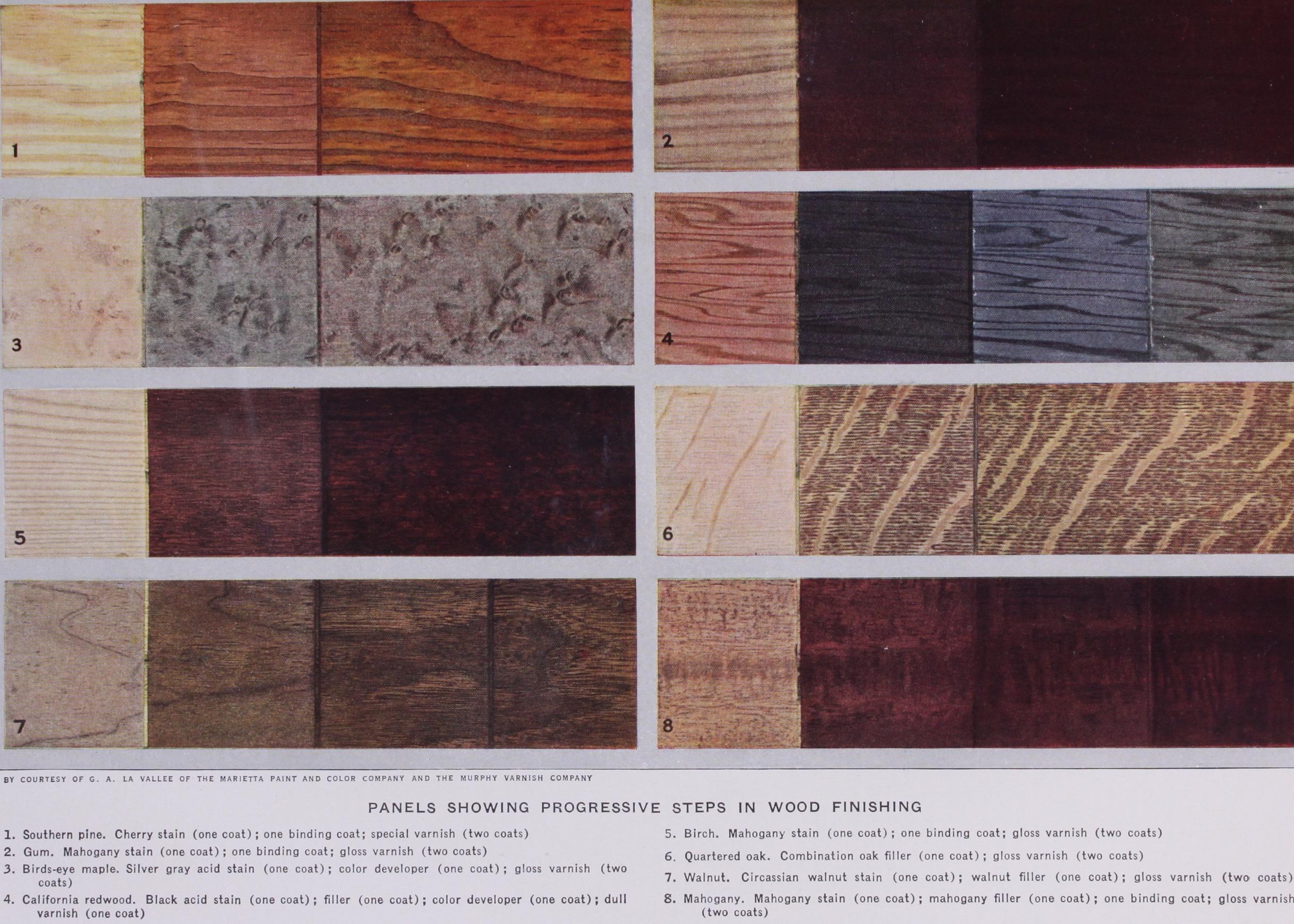

The varieties of woods used in construction at the present time differ widely in physical characteristics as well as in their chemical reactions. As a consequence different methods of initial treatment or preparation are required. Wood finishers classify them as "soft" or "hard," connoting generally their relative absorbent properties; "open" or "close" grain, indicating the relative solidity of the surface offered for finishing; resinous or non-resinous, the former class including woods such as cypress, which contain juices that are not really resins; and "plain" or "figured," these terms connoting the visual prominence of the wood structure.

All open grain woods require "filling" as a preliminary to the decorative treatment. This so-called grain consists of the sap ducts which have been laid open in cutting the lumber, and be comes apparent in those woods having large sap-ducts. These are chiefly the woods classified also as "hard woods." The prin cipal types encountered are butternut, walnut and the juglans family in general; oak, of all varieties; ash, elm, mahogany, rose wood, and chestnut. The following, classified as close grain woods, are, with the exception of maple, birch, cherry, gum and yellow pine, also classified as soft : bass, beech, birch, cedar, cherry, cotton wood, cypress, fir, gum, hemlock, holly, maple, the pines, poplar, redwood, spruce, sycamore and tulip. The preliminary treatment in all cases includes stopping of cracks and nail holes with putty coloured to match the finish to be applied, sandpaper ing with fine sandpaper to a smooth surface, removal of blemishes if the finish is to be transparent, and thorough dusting off.

Transparent Finish in the Natural Colour.—The woods suited to this treatment are those possessed of natural beauty due to their colour or configuration of grain. Those ordinarily selected for this treatment are the hard woods in general, sometimes in cluding close grained woods like the hard pines, the maples, some of the cedars, cherry, cypress and some types of birch. The nat ural beauty of certain of these woods, especially oak, is of ten enhanced by "quarter sawing" in which the boards are cut diag onally across the log.

The more open grain woods are "filled" with paste wood-filler, of which the best grades consist of finely powdered quartz ground to a rather stiff paste in a special varnish. The filler may be col oured or uncoloured. In the latter case, being transparent, it merely provides a smooth surface for varnishing. In the former, the grain is more clearly defined and very beautiful effects may be obtained by the addition of colour, aluminium bronze or white pigment. The paste filler is applied across the grain with a stiff brush, and after it has "set," but before it becomes hard, the sur plus is wiped off, again across the grain, with excelsior, burlap or similar material. After the remaining filler has become com pletely hard, the entire surface is sandpapered with fine sandpaper and carefully dusted off. The first coat of varnish is then ap plied, using a flat varnish brush. The grade of varnish used de pends upon the finish desired. If the work is to be rubbed or polished, the varnish selected is a rubbing and polishing grade; if not, a softer and more elastic grade of interior varnish is usually preferred. In either case three or more successive coats are ap plied if a good finish is desired. Sufficient time is allowed for the complete drying of each coat—from 24 to 48 hours, depending upon the character of the varnish. However, quick drying var nishes made from synthetic resins, in which the drying time has been reduced to a few hours, have recently been introduced.

If the more beautiful finish produced by rubbing is desired, each coat of varnish after thorough drying, is rubbed with pow dered pumice stone and water or pumice stone and oil to produce a perfectly smooth surface. If a dull or low lustre finish is de sired, the final coat is rubbed only. If a lustrous finish is required the rubbing of the final coat is followed by polishing with rotten stone and oil. For both rubbing and polishing a pad made by fastening felt to a flat block is most serviceable, and for sand papering a similar pad is serviceable, the sandpaper being laid over the felt.

Staining.—The modern tendency in wood finishing is to colour the wood before applying the finish. In fact, it has long been the practice to stain many of the choicer woods, such as mahogany, walnut, rosewood, oak, etc. The natural colour of mahogany is a very pale yellow, but staining of this wood has been so long in vogue that the very name suggests red, though in recent years brown has become the more popular colour. Certain woods are also stained to imitate rarer varieties, as, for instance, birch and maple to simulate mahogany, or birch in imitation of cherry.

The older craftsmen employed a variety of vegetable dyes and various chemicals to produce the effects they required, but with the invention of coal-tar dyes, in their great variety and beauty, the older art has largely fallen into disuse. Many of these so-called "aniline dyes" are now sold as powders under the names of the woods on which they are supposed to be used, as, for example, mahogany brown, mahogany red, walnut brown, oak stain, etc. Most of the stains used in ordinary finishing, however, are pur chased ready for use from the manufacturers, who furnish them in endless variety.

Stains are of five types, selected according to the woods on which they are to be used—water stains, oil stains, spirit stains, acid stains, and penetrating stains, the last including alkaline stains. The water stains are usually prepared by the user by dis solving the dye in water, though they can be purchased in solution; the rest are obtained ready for use from the manufacturer. The oil stains are generally preferable to the water stains, since they do not "raise the grain" of the wood like the latter, which neces sitate sand-papering. The water stains nevertheless are preferred for the light coloured soft, absorbent woods, because oil has a tendency to darken these. Where lacquer is the finishing material, water stains are usually preferred, because of the better adhesion of the finish after their use. Many stains are also made with the same insoluble pigments that are used in the manufacture of paint; and finally, varnish stains are procurable for first coating in which the stain and the first coat of varnish are applied in one operation. Acetic acid is usually added to some stains to increase the solubility of the dyes not readily soluble in water; and oil or spirit—usually turpentine or an alcohol—is substituted for water in other stains for similar reasons.

With water or spirit stain the procedure is to apply the stain with a soft brush. Skill is required here to obtain evenness of distribution. A coat of dilute shellac varnish is then applied. This serves to stiffen the wood fibres that have been "raised" by the stain, so that they may be easily cut. The surface is then lightly sand-papered with fine sand-paper. The transparent wood filler is next applied if required, followed by a second application of stain, if required, and a second light sand-papering. The var nishing follows—two, three, or more coats, either rubbed or un rubbed, according to the finish desired.

The term enamel, originally applied to fused vitreous coatings on metals, is now also used for opaque pigmented varnish coatings. Such finishes were formerly produced with spirit varnishes (prin cipally dammar) but are now commonly produced with prepared enamels. As found in the market, the better grades of these con sist of zinc oxide or the best quality of lithopone ground in a spe cial rubbing varnish.

In producing the finish the wood is first filled, if necessary. One or two coats of flat drying oil paint are then applied, followed by two or more coats of the enamel, according to the quality of finish desired. These coats may be rubbed, as in clear varnish finishing, and the final coat polished ; or they may be applied suc cessively without further treatment.

Graining.—This type of finish, once universal, is now rarely used, except where necessary to match old work. Its purpose is to imitate with cheaper woods the colour and figuration of more ex pensive woods. Expert grainers of the old school can so closely simulate rare and costly woods that it is almost impossible for the eye alone to distinguish between them. Woods usually selected for the purpose are the common soft close grained woods, such as pine, poplar, soft maple, etc. A "ground colour" closely resembling the prevailing colour of the wood to be imitated is first applied, two or more coats being necessary. These colours may be bought ready for use. Specially prepared graining colours to match the deeper shades of the wood to be imitated are then applied evenly with a soft flat brush. This process is called "rubbing in," from the fact that paste colours formerly used, necessitated rubbing to spread them. A comb of steel or hard rubber is then passed over the portions of the work that are to be left plain. For imitating the less open grain hard woods, such as walnut, cypress, yellow pine; cherry, etc., the steel comb is covered with a rag. Rags are also used for wiping out "heart-grains." Then by the use of combs and wiping rags the expert grainer can closely imitate the grain pattern of any wood. The finishing touch is added by "overgrain ing," to soften and blend the work, with water colour, to which a little beer or vinegar has been added. For commercial work ma chines, stencils and transfers are available which fairly imitate the grains of various woods. The chief objection to them is that the pattern is monotonously duplicated. The most successful of these is perhaps the "graining wheel," consisting essentially of a printer's ink roller bearing the grain pattern in relief. A more recent invention consists of a steel roller which stamps the grain pattern into the substance of the wood, which is then filled, stained and treated exactly like the wood imitated. The completed work is preserved by varnishing.