Rating and Performance

RATING AND PERFORMANCE It is shown above that the brake horse power of a single-acting four-stroke petrol engine with N cylinders is expressed by : • • • snNXio (I) For rating purposes in car and motor-boat competitions it was found necessary at an early date to have some formula which should give simply, and in terms of some easily ascertainable dimensions of the engine, the maximum practicable horse-power, to a reasonable degree of approximation.

An examination by Sir D. Clerk, of the performance of about Ioo engines in 1905-6 showed at that time a prevailing piston 11X2s speed (_ ) I2 of roundly i000 feet per minute, with a brake mean effective pressure, rip, averaging 7o lb./sq.in. If, in (I) above, 6000 be substituted' for sn and 7o for rip, the equation will be found to reduce by common arithmetic to:— In 1906, the Royal Automobile Club decided to take o.4 as the coefficient instead of 0.417, and thus was obtained the famous R.A.C. Rating Rule for petrol engines, viz.: R.A. C. Rating = (3) where d is the cylinder bore in inches. This simple formula was also adopted by the British Treasury for taxing purposes, and has continued in operation up to the present time.

In passing, it may be noted here that at the end of 1927 there were running on the 178,361 miles of roads in Great Britain, a total of 1,694,000 licensed motors, as compared with 270,000 in 1919. The amount received by the British Treasury for motor licences for the year ending Nov. 3o, 1927, totalled The R.A.C. and Treasury rating formula, depending only upon the number and the square of the bore of the cylinders, imme diately caused petrol engine designers to concentrate on the problem of obtaining a maximum output from the minimum cylinder.

In this direction extraordinary success has been achieved, particularly by British designers; even by 1912 tests of normal engines at Brooklands showed a power output averaging nearly 5o% greater than that given by the R.A.C. formula, individual cases showing an excess of even i00%. Much of the improve ment has resulted from recognition of the necessity of design ing an engine not only as a prime mover, but also as a highly efficient pump; the increased pumping, i.e., volumetric efficiency, coupled with increased revolution speeds, has enabled remark able results to be achieved ; a notable early instance is furnished by a Vauxhall four-cylinder 3.54 in. X 5.12 in. racing engine, with a Treasury rating of, roundly, 20 H.P., which developed 90 B.H.P.—or 42 times its rating—when running at 3,60o rev. per min.

After the outbreak of war in 1914 it soon became manifest that the high-speed petrol engine was of fundamental importance in connection with road transport, aircraft, and later "tanks," and all available engineering skill was for some years again con centrated upon effecting still further improvements. There have resulted very high-speed motors, both small and large, of extra ordinarily high power output in relation to their size and weight, rivalling in efficiency the largest slow-running stationary types. Many examples can be cited from the tiny four-cylinder, seven H.P. and eight H.P. Austin and Singer designs respectively to the six-cylinder 35/I20 horse-power Daimler engine, the lower figure representing the R.A.C. rating.

Even more striking is the astonishing success achieved with the petrol engine as applied to racing aircraft; thus the 1928 12 cylindered "broad-arrow" water-cooled four-stroke single-acting Napier "lion" racing aero-engine with a bore of 5.5 in. and stroke of 5.125 in., using a compression ratio of I o : I, and a fuel composed of 7 5 % petrol, 2 5 % benzol, and a small "dope" of lead tetra-ethyl, and weighing 835 lb., had a power output of B.H.P. at 3,30o rev. per minute; or I B.H.P. for each 0.954 lb. of weight. (See AERO-ENGINE.) In. Table III. some figures are given for a few typical modern engines ; the values in the extreme right-hand column depend on the nature of the service demanded from the engine ; thus petrol engines for marine work, or for driving heavy road lorries are called upon for a much heavier continuous power output than are the engines of normal motor-cars, and are accordingly more robustly built and are in general run at somewhat slower speeds. At the extreme top of the range of output performance is the racing aero-engine from which all that is demanded is an abso lutely maximum output during a very short period of time.

Capacity Rating.

A mode of petrol engine rating much employed for classifying purposes is that obtained by taking the total volume swept out by the pistons in one stroke of the engine, and this is termed the "capacity" rating. It is evidently expressed by piston area X stroke X number of cylinders, or, in symbols :— If d and s be in inches, the value is expressed in cu.in. It is, however, more usually expressed in cubic centimetres ; so that d and s, denoting the bore and stroke in millimetres, and N being the number of single-acting four-stroke cylinders, we have:— Capacity Rating = X io (5) or, in litres, = X ro 10(6) A useful expression of performance is to state the B.H.P. per litre of capacity; this is given in the extreme right-hand column of Table III., and is of course at once obtained by dividing the B.H.P. by the capacity. If the general formulae for B.H.P. (Eq. I) and for capacity (Eq. 4) be employed we get the useful relation :— wherein Tip is the brake mean efficient pressure in lb./sq.in., and n is the number of revolutions per minute.

Small Motor-car Engines.

A recent 15.9 Morris engine, a typical engine of the average motor car, is a four-cylindered, four-stroke vertical unit of 3.15" (8o mm.) bore, and 4.92" (12 5 mm ) stroke, and accordingly has a Treasury rating of and a capacity of litres.The four cylinders are cast en bloc with side-by-side inlet and exhaust valves cam-driven through adjustable tappet rods; the valves are all of the same size, and their springs and stems are enclosed by a readily removable cover-plate to exclude dust and retain oil. The cylinder heads are detachable, facilitating greatly decarbonisation and access to the valves.

The power output by bench tests is as follows:— At rev. per min. . . . i,000 1,500 2,000 2,500 B.H.P. . . i4 0 21•5 The off-set hollow crankshaft is borne in three bearings which are housed in the lower part of the cylinder block, thus giving great rigidity to the engine. The connecting rods are of duralumin, and all main and big-end bearings are of white metal in bronze shells Aluminium-alloy pistons are used. Lubrication is f orced, by a drowned plunger pump driven by an eccentric on the cam shaf t,—to the three main crankshaft bearings, the four big ends (via the hollow crankshaft), and also to the camshaft bearings. The pump in-take is through a gauze fitter easily removable for cleaning; a gauge on the dashboard of the car indicates the oil pressure in the circulating system while running. Ignition is by the usual H.T. (high-tension) magneto.

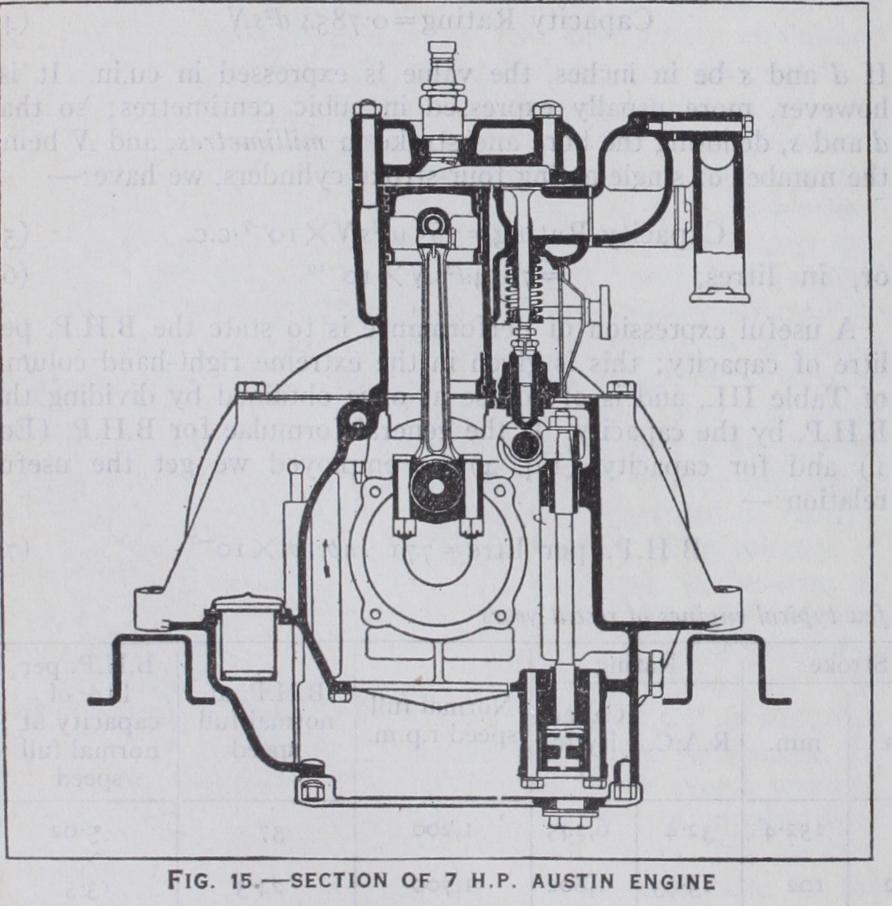

The "Baby Austin" Engine.—The performance of the modern tiny motors typified by recent Austin and Singer designs is so remarkable as to merit special notice. A section of a seven H.P. Austin small-car engine is given in fig. 15. The four en bloc cylinders of 2.2 in. bore and 3•o in. stroke (see table) are fitted with a detachable head. The pistons are of aluminium alloy. The side-by-side valves are cam-operated in the usual manner. Lubri cation is by a drowned oil-pump driven from the camshaft as indicated, and ignition is by H.T. magneto. Thermosyphon cooling with a "film" radiator and fan. The four-throw crankshaft is borne in two roller bearings. The mixture is supplied by a Zenith carburetter. The power output is:— At rev. per min. . . i,000 1,500 2,000 2,500 2,800 B.H.P. . 3.8 6.2 8.7 11.0 12 •o (max.) This miniature engine propels its car containing three or four adults with ease at 35 miles per hour on an ordinary good road surface, with a petrol consumption of 4o-5o miles per gallon.

The Eight H.P. Singer "Junior."—A recent design of this car has an engine of the same bore as the seven H.P. Austin, but with the larger stroke of 3.38 in. (see table). The cylinders and crankcase form a single casting and an aluminium casing houses the timing gear and forms the front support of the engine. The short stiff crankshaft is borne in two solid white-metalled bearings. The pistons are of cast iron with three spring rings, the lowest ring securing the gudgeon pin. The connecting-rod big end bear ings are of white metal in bronze shells. The valves in this engine are overhead and inclined and are operated by rockers ; the over head camshaft, oil-pump, magneto, and starting and lighting dynamo are all driven from an intermediate shaft placed above the front end of the crankshaft and driven by it through helical gearing; the drive from the intermediate shaft to the overhead camshaft is by double roller chain fitted with an automatic ten sioning device. The detachable cylinder head is a single casting carrying the camshaft in three bearings, and is fitted with renew able valve guides. Lubrication is by pump and troughs; the pump intake draws the oil through an easily removable gauze filter, and delivers into four troughs into which the connecting rods dip, and also up to the overhead camshaft and valve rocker bearings. The oil pressure is indicated by a gauge on the dashboard. Cooling is on the "convection" or "thermo-syphon" system. Ignition is by H.T. magneto. A Solex horizontal carburetter is used. The engine is enclosed, dust-excluding and oil-retaining. The power output is : At rev. per min. i,000 1,500 2,000 2,500 3,000 3,250 B.H.P. . . 6.2 9.3 12.4 14.9 16.2 16.4 (max.) and in the autumn of 1927 a car fitted with one of these very small engines accomplished a run from London to Edinburgh, and back in 244 consecutive hours, corresponding to an average speed throughout of about 33 miles per hour.

Sleeve Valve Engines.

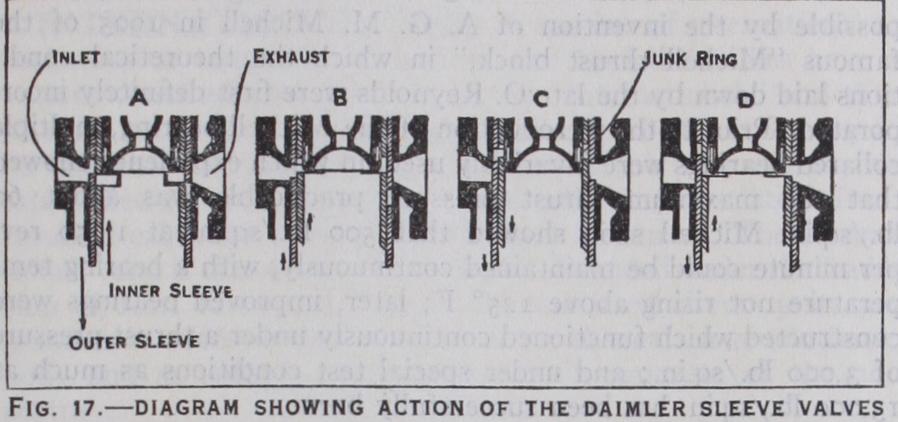

In these the poppet valves are re placed by ported sliding sleeves which, in the single-sleeved engine is the working barrel of the cylinder and has a motion partly reciprocating and partly angular, while in the double-sleeved engine both the ported working barrel and the second ported sleeve enveloping it have a simple axial reciprocating motion.Space permits but a brief reference to the single-sleeved type, but the Burt-McCollum design has been successfully employed for some years in the engines of Barr and Stroud, Caledon, Argyll, and Karrier; an exhaustive account of this type is given by Ensor in the Proc. Inst. Auto. Engrs. (1927-8).

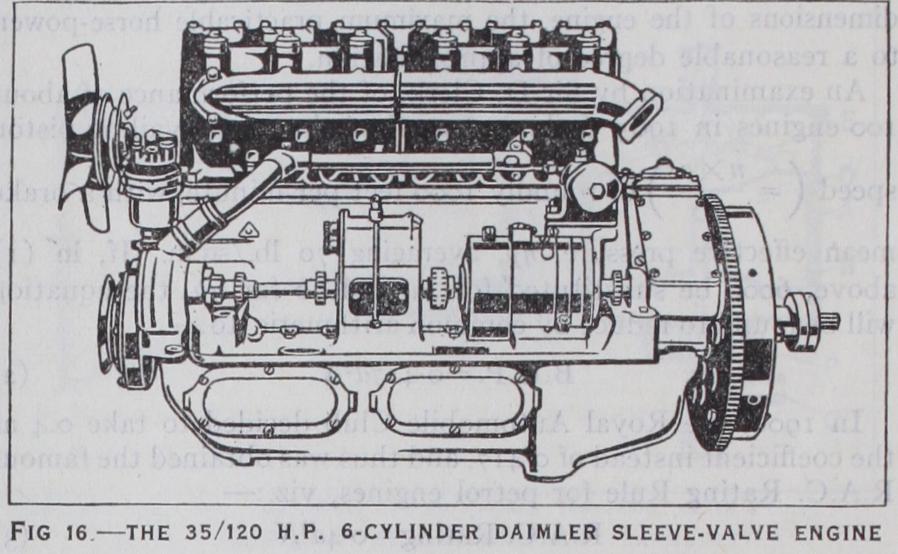

The Daimler-Knight Double-sleeve Engine.—Used with great success since 1908, the smooth running "Silent Knight" engine is deservedly famous. The four-stroke, single-acting, six-cylindered, h.p. design, illustrated in fig. 16, has a bore of 3.85 in. a stroke of 5.13 in., and consequently a Treasury rating of 35.5. Bench tests show that at a speed of 3,00o rev. per min. the engine develops roundly 120 b.h.r. At a car speed of 6o miles per hour the engine runs at 2,14o rev. per minute. The manner in which the ported light steel sleeves regulate the inlet and exhaust periods is clearly shown in fig. 17.

The inlet port opening and the exhaust port closing at the beginning of the suction stroke is shown in A. The inner sleeve is rising and the outer sleeve is descending. The exhaust is shown closed and the inlet closing at the beginning of the com pression stroke in B. The ports in the inner sleeve are passing up into the cylinder head, where they are sealed by the junk ring during the period of maximum pressure and temperature at the beginning of the firing stroke (C). In D, the exhaust is already well opened at the beginning of the exhaust stroke. The sleeves are now again moving to the position shown in A.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-E. Sorel, Carburetting and Combustion in Alcohol Bibliography.-E. Sorel, Carburetting and Combustion in Alcohol Engines (1907) ; D. Clerk and G. A. Burls, The Gas, Petrol and Oil Engine, vol. ii. (1913) ; G. A. Burls, Aero Engines, 9th ed. (1917) ; Modern Mechanical Engineering, vol. vi., ed. A. H. Gilson and A. E. H. Chorlton, G. A. Burls, "Aero Engines" (1923) ; H. R. Ricards, The Internal Combustion Engine, vol. ii. (1923) ; A. W. Judge, Automobile and Aircraft Engines (1924), The Testing of High-Speed I.C. Engines (1924). See also "The Automobile Engineer," "The Motor," "The Autocar," "Gas and Oil Power," "Flight," "The Marine Engineer," "The Motor Ship," also, "Proceedings of the Institution of Automobile Engineers" from 1906.