Sub-Order Ii Apocrita

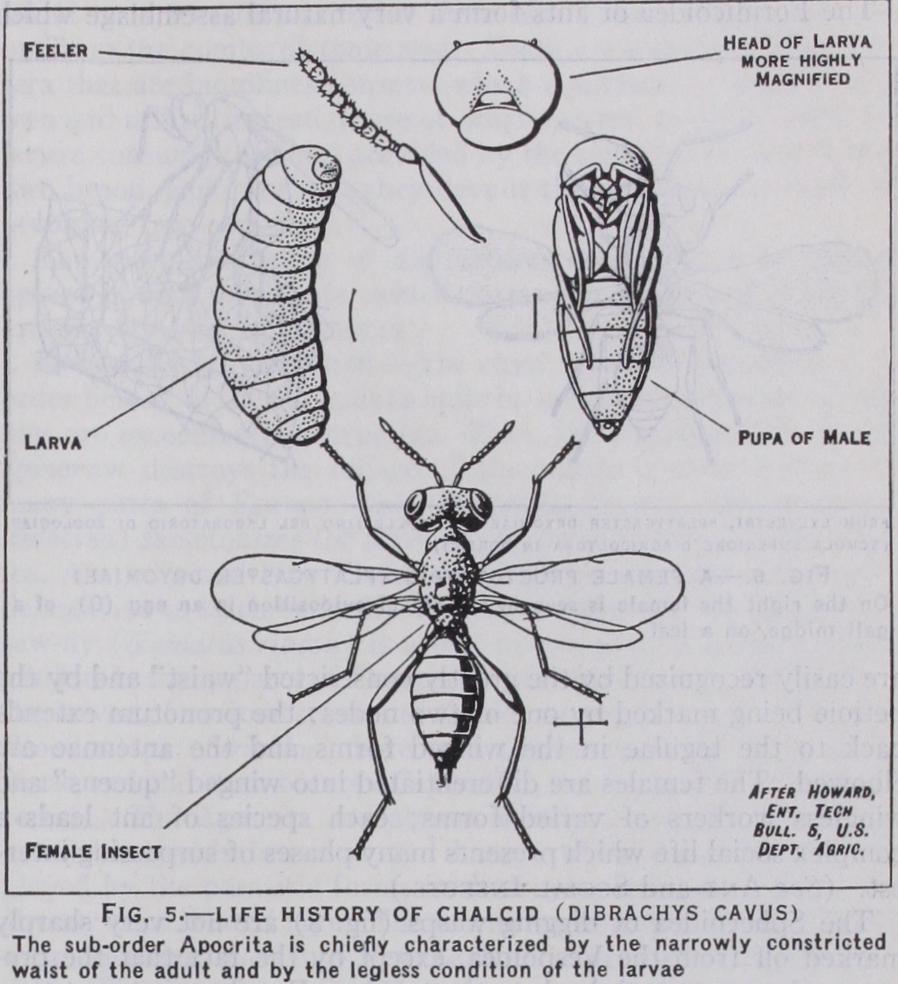

SUB-ORDER II. APOCRITA Abdomen with a basal constriction or waist: trochanters z- or 2-jointed. Larvae embryonic or vermiform without legs.

The great group is divisible into the Parasitica which generally have 2-jointed trochanters and the Aculeata or stinging forms in which the trochanters are single jointed. The Parasitica include the following super-families.

The Ichneumonoidea have the pronotum extending back to the tegulae, the antennae are not elbowed and the fore-wings have a dark mark or stigma (fig. 7) . Without exception the larvae of all members of this group are parasites preying upon some stage in the life-cycle of other insects and are consequently of great eco nomic importance. (See ICHNEUMON FLY.) The Cynipoidea include the gall-wasps or gall-flies which differ from the ichneumons in the absence of a stigma to the fore-wings and in the trochanters being usually single-jointed, unlike other Parasitica. In the family Cynipidae many of the species lay their eggs in various plant-tissues which react in such a way that galls are produced wherein their development is completed. These galls are of characteristic form for each species, the oak apple and bede guar of the rose being familiar examples. Other members of the family are inquilines, living within the galls and bearing a close resemblance to the true makers of the latter. The Figitidae are mostly parasites of fly larvae and of aphides.

The Chalcidoidea or Chalcid-wasps are very small insects with elbowed antennae and with the pronotum not extending back to the tegulae. The group includes more than 16 families, most of the members of which are either parasites of the eggs, larvae or pupae of other insects or are hyperparasites. A small number are plant-feeders living in seeds, in figs, or form galls on cereals and grasses. The fig-insects are very numerous and certain of these are important agents in the pollination of the flowers, and have been introduced for economic purposes into lands where they were absent. The parasitic forms are of great practical value, in that they destroy vast numbers of injurious insects : certain of these exhibit the phenomenon of polyembryony, which is dealt with in the article INSECTS. Chalcids often exhibit beautiful metallic coloration, and can be recognized by the wing-veins being reduced to a single stem.

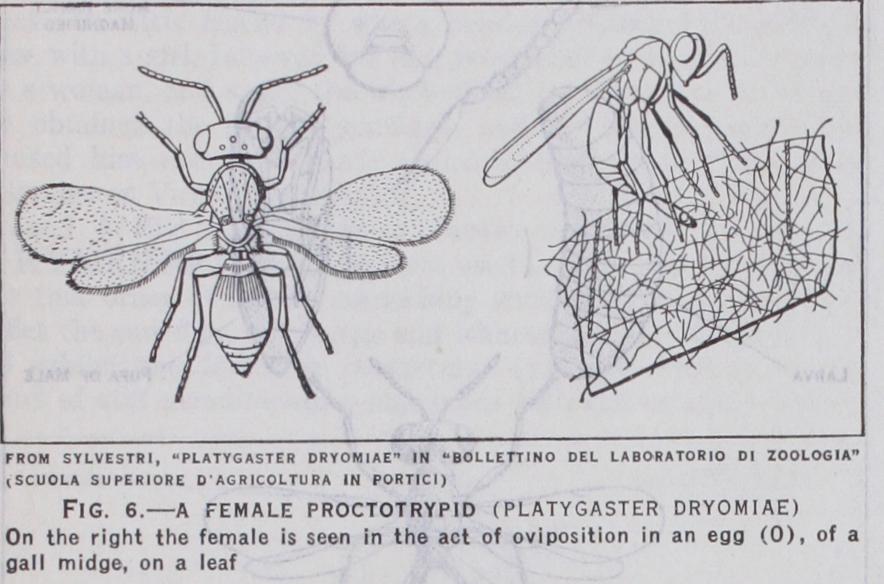

The Proctotrypoidea resemble the Aculeates in that the ovi positor issues from the apex of the abdomen, but the trochanters are 2-jointed. The first mentioned character, along with the fact that the pronotum reaches back to the tegulae, separates them from the Chalcids (fig. 5) . They are all very small or minute insects with greatly reduced venation and many are wingless. They live as parasites or hyperparasites of other insects, frequently in the eggs which they destroy in large numbers. The largest of the eight chief families are the Platygasteridae which mainly para sitize gall midges, their larvae often living in the brain or stomach of their hosts. Like the Chalcids the Proctotrypids are beneficial.

The succeeding super-families form the series Aculeata or sting ing Hymenoptera and in these the ovipositor issues from the apex of the abdomen, whereas in the Parasitica it issues some distance in front of the extremity.

The Formicoidea or ants form a very natural assemblage which are easily recognized by the greatly constricted "waist" and by the petiole being marked by one or two nodes: the pronotum extends back to the tegulae in the winged forms and the antennae are elbowed. The females are differentiated into winged "queens" and wingless workers of varied forms; each species of ant leads a complex social life which presents many phases of surpassing inter est. (See ANT and SOCIAL INSECTS.) The Sphecoidea or digging wasps (fig. 8) are not very sharply marked off from the Vespoidea, except by the fact that the pro notum does not reach back to the tegulae. For the most part they are to be regarded as beneficial insects from the fact that they are predators seizing other insects, which they carry off to their cells as food for their larvae. All are solitary insects which construct cells for their brood either below ground or in dry wood or stems. There are 12 families, the largest being the Sphecidae.

The Vespoidea include a large number of other digging wasps together with the social wasps. The pronotum generally reaches back to the tegulae but there are exceptions. Among the solitary species the Mutillidae are parasites in bumble-bees' nests and their females are wingless. Many of the Pompilidae provision their cells with spiders : they are often large insects with slender bodies and elongate hind-legs. The Scoliidae are robust, hairy wasps which often provision their cells with chafer larvae and chiefly inhabit warm countries. The Chrysididae or ruby-tailed wasps are beau tiful metallic green or green and blue or ruby insects, which lay their eggs in the nests of bees and wasps where their larvae either prey upon those of their hosts or devour their food. In this family only three or four abdominal segments are visible, the remainder forming a retractile tube containing the ovipositor. The true wasps have their wings folded lengthwise in repose and the fore-legs are of normal build—not specialized for digging as in the fossorial groups. The Vespidae or social wasps have "queens" and "work ers" as in ants, but both forms are winged, while the Eumenidae or solitary true wasps have no such differentiation into castes. (For the habits of these two families see WASP and SOCIAL INSECTS.) The Apoidea include the solitary and social bees which agree with the Sphecoidea in the pronotum not extending back to the tegulae but differ from them in having the hind tarsi dilated, while the hairs of the head and thorax are feathery or plumose. The glossa or tongue is well developed and often exceedingly long and the food consists of nectar and pollen. The larvae are fed upon a similar diet, except that the nectar is regurgitated as honey before being served to them. These substances are stored in the cells and the latter are never provisioned with animal food. Most bees are solitary in habit, but those of the families Bombidae and Apidae are social insects resembling ants and wasps in the occurrence of a worker caste. (See BEE and SOCIAL INSECTS.) Reproduction and Development.—One of the most interest ing facts with regard to reproduction in Hymenoptera, is the wide occurrence of parthenogenesis which obtains among members of all the great groups. The best known instance is in the honey-bee, in which the unfertilized eggs produce males (drones) : in the gall wasps or Cynipidae both sexes may be produced from unfertilized eggs and the generations which arise in this way alternate with those produced by the usual sexual method. In other of the gall wasps males are unknown : parthenogenesis is also very frequent in saw-flies and Chalcid wasps.

The larvae of the Symphyta are plant-feeders: those which feed openly on leaves are caterpillars, often with six or more pairs of abdominal feet (fig. 4) , but in the stem- and wood-borers these appendages are absent and the thoracic limbs are reduced to mere tubercles. Among the Apocrita tl-e larvae are usually hatched in immediate contact with an abt dance of food : they are in conse quence degenerate creatures devoid of limbs and of almost all traces of organs of special sense (fig. 5). In the parasitic groupb hypermetamorphosis (see INSECTS) is very frequent, the larvae being hatched in forms very different from that assumed in the final instar. In a few cases the eggs are laid away from the hosts and the larvae upon hatching are active creatures of the type termed a planidium. The planidium seeks out its host and having found it, assumes the legless maggot-like form common to all Apocrita. Some of the parasitic species live externally on their hosts and feed by piercing the integument with their mouth-parts, but the largest number arc endoparasites. In the latter case the female parent drives her ovipositor into the host and lays one or more eggs wherever the larvae will find abundant food. Many of the minute Chalcidoidea and Proctotrypoidea complete their devel opment within the eggs of other insects : others parasitize the larvae or pupae or, more rarely, adult insects, and death' of the host finally supervenes. The digging or fossorial wasps feed their brood with captured insects, which are stored away in cells along with a single egg : the wasp larva, upon hatching, thus finds its life's food-supply immediately at hand. The true wasps feed their brood with animal food including many insects, from time to time, very much as a bird does her fledglings, while bees entirely resort to honey and pollen. Thus, we find throughout the order a degree of care for the offspring, not attained in other insects, which has led to the development of social life in certain groups. When fully fed most Hymenoptera pupate in cocoons : silk is commonly used for their construction and among the ichneumon flies and their allies, these cocoons are often elaborate and beautiful objects.

Geographical Distribution.

Hymenoptera are found in all except the most inhospitable regions of the globe, but the order, as a whole, has not penetrated to such remote parts as have the Apterygota and Coleoptera. Bees, for example, are dependent upon the existence of flowering plants and are not found outside their range : some, such as the giant Xylocopa or carpenter bees are mainly tropical or sub-tropical, while bumble bees are essentially creatures of temperate climates and are generally confined to the mountains in the tropics ; they are absent from almost the whole of Africa, the plains of India and none are indigenous to Australia or New Zealand. The honey-bee (Apis mellifica) has been intro duced into most countries of the world, and some of the injurious saw-flies enjoy a very wide distribution, mainly through the agency of commerce. Among the Chalcid wasps the family Agaonidae or fig-insects occurs wherever trees of the fig kind flourish, but are not found outside that limit: certain other Chalcids (Eucliaridae) are mainly tropical and are confined to where their particular ant hosts flourish. Perhaps the most interesting fact concerning the distri bution of Hymenoptera is the great paucity of forms found in New Zealand, where they are represented by little more than 30o spe cies, as compared with over 6,000 found in Australia.

Geological Distribution.

Forms ancestral to Hymenoptera are represented by the extinct order Protohymenoptera, whose re mains occur in the Lower Permian of Kansas. The first true mem bers of the order to appear in geological history are wood wasps of the genus Pseudosirex from the Upper Jurassic of Bavaria. In Tertiary times the order is represented by ants, bees and other forms which differ relatively little from those found living to-day.

Natural History.

Hymenoptera are mostly of small or mod erate size : only a few members of the order are very large insects, the giants being certain of the saw-flies and digging wasps of the family Pompilidae, some of the latter attaining a length of three inches. On the other hand, many of the parasitic forms are among the smallest of all insects, notably those which live as egg-para sites ; certain Chalcid wasps of family Mymeridae or "fairy flies" measure only • 2 I mm. in length.Hymenoptera are essentially terrestrial and aerial in habit.

The only exceptions are those which parasitize the larvae or eggs of aquatic insects : the "fairy fly" Polynema natans swims read ily beneath the water by means of its wings and seeks out the eggs of the water boatmen (Notonec ta) as the host for its larvae. In a number of species the parasitic groups greatly exceed the remain der of the order. No order of terrestrial insects escapes their at tacks, and even larvae deep in the soil or boring in the solid wood of trees are by no means immune. As a rule the length of the ovipositor is greatest in those parasites such as Thalessa and Rhyssa which have to force this organ through a depth of wood, in order to reach their hosts (fig. 7) . One of the most remarkable cases of parasitism is found in a proctotrypid, Riela manticida which, according to L. Chopard, passes its development in the eggs of the praying mantis. The adult parasites, upon emergence, make their way to a mantis, upon whose body they settle down : in this situation they cast off their wings and live ectoparasitically. If the mantis be a female which has commenced egg-laying, the Riela migrates to the extremity of the body, in order to lay its eggs in the viscid mass of the mantis' egg-capsule as it is being formed. Parasites which settle upon male mantids are probably short-lived and perish. The digging wasps store their cells with other insects or spiders and as a rule they sting their prey first and reduce it to a condition of immobility without actually killing it : in other cases the prey is killed, but since it retains its fresh condition up to several weeks, it is presumed that the injected venom exercises an antiseptic influence. Fabre's observations upon the Sphex (Ammophila), which stings its caterpillar prey in successive seg ments of its body, have often been quoted. The French ob server maintained that this in sect (fig. 8) had a sort of intui tive knowledge of the inner anatomy of its victim, the stings being administered in the gangli onic nerve centres, thereby in ducing paralysis, a conclusion which is scarcely warranted by the facts at his disposal. The number of times a prey is stung appears to vary from once up to about a dozen : in addition to being stung the victim is vigor ously pinched by the jaws of the Sphex particularly when it has only been stung a few times and subsequent paralysis occurs in each case. The nature of the prey of digging wasps is often very constant for particular species. Thus Philanthus triangulum stores its nest with honey-bees, while species of Bembex prey upon large Diptera and the powerful Pep sis femoratus stores its burrows with the great Tarantula spiders.

Among bees, wasps and some ants, the capacity for stinging is employed for defensive purposes and the usual glands which are found at the base of the ovipositor are especially large in these insects. Their secretions have irritating properties to which the sting is due, those of ants containing formic acid.

The nest-building habit is another feature of Hymenoptera. Digging wasps make simple burrows in the ground, and many bur rowing bees make branched tunnels. Other bees excavate wood or make their brood-chambers in hollow stems, while the true wasps work up dry fragments of wood with their saliva to form a sort of paper with which they construct the cells of their nest. The social bees secrete wax from their own bodies with which they build up the combs of their nest. There are numerous Hymenop tera that are inquilines—insects which construct no nests of their own and utilize, instead, those of other species : in some cases their larvae consume the food provided by the rightful owners for their own brood, and in others, they devour the larvae of the host thus becoming true parasites.

The most interesting of all features associated with Hymen optera is their social life, which forms the subject of a separate article. (See SOCIAL INSECTS.) Economic Importance.—The chief injurious members of the order belong to the Symphyta and the larvae of a number of saw flies are exceedingly destructive. Thus, the turnip saw-fly Athalia spinarum destroys the foliage of the turnip crop in Britain and many parts of Europe : the pear slug saw-fly (Eriocampoides limacina) skeletonizes the leaves of pears in Europe, North Amer ica, Australia and New Zealand and Lygaeonematus erichsonii is destructive to larch on both sides of the Atlantic. The gooseberry saw-fly (Nematus ribesii) is a well known pest of gooseberries in gardens in many parts of Europe, as well as in North America, and the larvae of various species of Lophyrus are destructive to pines. Wood-wasps (Siricidae) bore into timber in many parts of the world and the stem-borers (Cephidae), are especially injurious to cereals. The Apocrita are almost wholly beneficial insects, the honey-bee yields bees-wax and honey, while the important role played by the parasitic forms in destroying injurious insects, has already been dilated upon. The recent introduction of the Chalcid wasp Aphelinus mali into New Zealand is an example of the prac tical utilization of parasitic Hymenoptera, and the species in ques tion has now largely controlled the woolly aphis of the apple in that territory. Among other Chalcids certain fig-insects (Blasto phaga) are employed in the pollination of the flowers of the fig, and have been previously mentioned. On the other hand, a small num ber of Chalcids are injurious, notably those whose larvae live in seeds such as species of Megastigmus which attack those of coni fers, while larvae of Harmolita form stem galls on cereals and grasses.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-In

an order so extensive and diverse as HymenopBibliography.-In an order so extensive and diverse as Hymenop- tera the reader will find very few comprehensive works, the literature mainly dealing with individual groups. The European species are monographed by E. and E. Andre, Species des Hymenopteres d'Europe et d'Algerie (1879-1913) and the world's species are catalogued by C. G. de Dalla Torre, Catalogus Hymenopterorum (Leipzig, 1892 1902) . A useful guide to the North American forms is provided by H. L. Viereck and collaborators in The Hymenoptera or Wasp like Insects of Connecticut (Bull. 22 State Geol. and Nat. Hist.Survey: Hartford, Conn., 1916) and for their classification consult W. H. Ashmead', Proc. U.S. Nat. Mus. xxiii., 1901. For the saw-flies and gall-flies the accounts given in C. Schroder's Insekten Mittel europas, vol. iii. (Stuttgart, 1914) are concise and well illustrated, while the British species are described by P. Cameron, British Phyto phagous Hymenoptera (London, Roy. Soc., 1882-92), which is pro vided with accurate coloured plates. A useful popular account of the galls produced by Cynipidae is E. T. Connold, British Plant Galls (1909) . For the North American galls see M. T. Cook, Galls and Insects Producing them (Ohio Nat., vols. ii.—iv., 1902--o4), and A. Cosens, A Contribution to the Morphology and Biology of Insect Galls (Trans. Canad. Inst. vol. ix., 1912). For parasitism and the forms exhibiting this habit the following works are important: W. H. Ashmead, Classification of the Chalcid Flies (Mem. Carnegie Mus. I, 1904) and the same author's Monograph of the North American Proctotrypidae (Bull. 45, U.S. Nat. Mus. 1893) ; L. O. Howard, The Biology of the Hymenopterous Insects of the family Chalcididae (Proc. U.S. Nat. Mus., xiv., 1891) ; L. O. Howard and W. F. Fiske, The Importation into the United States of the Parasites of the Gipsy Moth, etc. (U.S. Dept. Agric., Entom. Bull. 91: 1911) ; other refer ences are given in the article ICHNEUMON-FLY (q.v.) .

The Aculeata have a very extensive literature and among the more important works are: E. Saunders, Hymenoptera Aculeata of the British Islands (1896) ; H. St. J. Donisthorpe, British Ants (1927) ; W. M. Wheeler, Ants (191o) ; P. and N. Rau, Wasp Studies Afield (Princeton, 1918) ; G. W. and E. G. Peckham, Wasps, Social and Solitary (1905) ; for other references see SOCIAL INSECTS.

In addition to the foregoing numerous observations on the habits and behaviour of Hymenoptera are given in J. H. Fabre, Souvenirs Entomologiques (1879-1905), many of which are translated into English. (A. D. I.)