Terrestrial Magnetism

TERRESTRIAL MAGNETISM). Inclinometers are of two distinct classes, viz., dip circles and induction inclinometers, often called earth inductors.

Dip Circle.

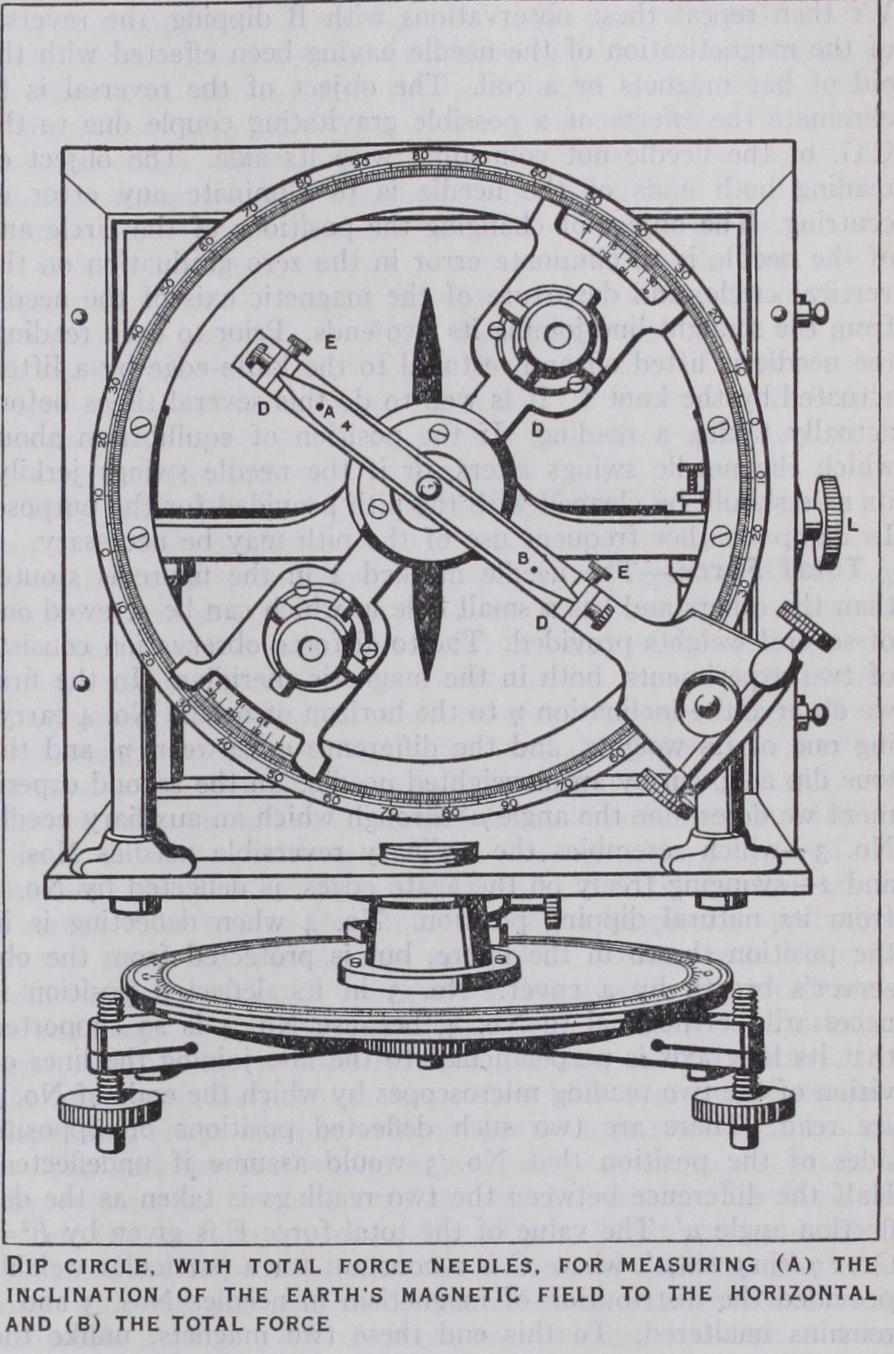

The instrument shown in the fig. is intended for the determination of total force as well as dip. With this instru ment four needles are provided. Two are seen in the illustration. One of these, No. 4, held between the clips DD, is a total force needle, but we may suppose it non-existent, as it is not represented in the ordinary dip circle. In modern circles of the pattern shown, the needle is a flat lozenge-shaped piece of steel, about 9 cm. long and o• I cm. thick. The axle, which is made of hard steel, projects on either side of the needle, and where in contact with the agate knife-edges in which it rolls has a diameter of about o•o5 cm. The two ends of the needle are marked A and B for purposes of distinction. When in position inside the box the axle of the needle is on the axis of the vertical divided circle. The needle shown in the background of the illustration happens to be vertical. When a dip observation is being made the needle takes up the appropriate inclination, and the positions of its ends are observed with the two reading microscopes, carried by the same movable piece as the two diametrically opposite verniers. The circle is divided to o.5°, and the vernier, divided from o to 3o, enables minutes of arc to be read off. The reading should always be taken with a slight swing on the needle, the adjustment being made with the tangent screw until the wire in the reading microscope seems to bisect the (small) arc of vibration. Suppose the inclination observed when the plane in which the needle swings—which is necessarily parallel to the vertical circle—is inclined at an angle a to the magnetic meridian, the observed dip, and the true dip I in the magnetic meridian are connected by the relation cot =cos a cot I. If then be the dip obtained when observing in a plane perpendicular to the first one, we similarly get cot sin a cot acot I. Hence for all values of a, i.e., for any pair of orthogonal planes, we have cot cot + cot It follows that no plane can give a smaller dip than the magnetic meridian, and in the plane perpendicular to the meridian the dip is i.e., the needle is vertical. Circumstances may arise in which observing out of the meridian in two perpendicular planes has advantages but the usual practice is to observe only in the meridian. The meridian is sometimes obtained with the aid of an auxiliary compass needle, but it is usually determined by means of the result that the needle becomes vertical in the plane perpendicular to the meridian. The position where this occurs is read off on the horizontal circle, which is similarly divided to the vertical circle. Rotating the instrument through a right angle, as shown on the horizontal circle, we bring the vertical circle into the desired meridian, and by the use of a stop, not shown in the figure, can recover this position when desired. Rotating the instrument backwards from this position we again bring the vertical circle into the magnetic meridian, and secure the recovery of this position by a second stop. At a fixed observatory one determination of the magnetic meridian may serve for months.

A satisfactory dip observation involves a number of readings. Calling the flat surface of the needle bearing the letters A and B the face, and that side of the box containing the needle which is next the vertical circle the face of the instrument, we take the following readings with A dipping, at least two readings being taken of each end: Instrument facing east, face of needle to face of instrument ,, ,, west, ,, ,, ,, ,, ,, ,, ,, „ „ west, „ „ „ „ back „ „ ,, ,, ,, ,, ,, ,, ,, We then repeat these observations with B dipping, the reversal of the magnetization of the needle having been effected with the aid of bar magnets or a coil. The object of the reversal is to eliminate the effects of a possible gravitating couple due to the C.G. of the needle not coinciding with its axle. The object of reading both ends of the needle is to eliminate any error of centring. The object of changing the positions of the circle and of the needle is to eliminate error in the zero graduation on the vertical circle, and departure of the magnetic axis of the needle from the straight line joining its two ends. Prior to each reading, the needle is lifted off and restored to the knife-edge by a lifter, actuated by the knot I. It is well to do this several times before actually taking a reading. If the position of equilibrium about which the needle swings alters, or if the needle swings jerkily, its axle should be cleaned with the pith provided for the purpose. In damp weather frequent use of the pith may be necessary.

Total Force.

The needle marked 4 in the figure is stouter than the others and has a small hole in which can be screwed one of several weights provided. The total force observation consists of two experiments, both in the magnetic meridian. In the first we observe the inclination 77 to the horizon of needle No. 4 carry ing one of its weights, and the difference ,u between i and the true dip as given by an unweighted needle. In the second experi ment we determine the angle ,u' through which an auxiliary needle No. 3—which resembles the ordinary reversible needles Nos. i and 2-swinging freely on the agate edges, is deflected by No. 4 from its natural dipping position. No. 4 when deflecting is in the position shown in the figure, but is protected from the ob server's breath by a cover. No. 3 in its deflected position is necessarily orthogonal to No. 4, because No. 4 is so supported that its long axis is perpendicular to the line joining the lines of vision of the two reading microscopes by which the ends of No. 3 are read. There are two such deflected positions on opposite sides of the position that No. 3 would assume if undeflected. Half the difference between the two readings is taken as the de flection angle ,u'. The value of the total force F is given by Ccos n/sin µ sinµ', where C is a constant for a particular weight, provided the distribution of magnetism in needles Nos. 3 and 4 remains unaltered. To this end these two magnets, unlike the others Nos. i and 2, never have their magnetism reversed. The constant C is determined from observations at a base station where F is known. In reality C varies slightly with the local value of gravity, but hardly to an extent that matters.The dip circle can be adapted for use at sea by having the ends of the axle of the needle carried in jewelled holes. The instru ment, of course, is carried on gimbals. A modification of the original sea pattern instrument, devised by Robert Were Fox, to which its inventor, Captain E. W. Creak, R.N., assigned the name of the Lloyd-Creak, has been a good deal used. To get rid of friction, a knob on the top of the box is rubbed with a cor rugated ivory disc. A distance between the deflecting and de flected needles suitable for higher latitudes may be too small near the equator, where the total force is relatively small. This difficulty has been surmounted in the sea dip circles used by the Carnegie Institution by mounting the deflecting needle excen trically in a metal box, which is attachable to the frame of the dip circle, with the side to which the deflecting needle is nearest either adjacent to or remote from the deflected needle. This gives a choice between two deflection distances.

Induction Inclinometer.

If a coil of insulated wire is spun about a diameter, an alternating current is induced unless the diameter is parallel to the lines of force of the earth's magnetic field. Hence if the axis about which the coil spins is adjusted until there is no deflection in a sensitive galvanometer, connected to the coil through a commutator by which the alternating cur rent is converted into direct current, then the axis must be parallel to the lines of force of the earth's field. The inclination of the axis to the horizon is then the dip. The introduction and improve ment of the induction inclinometer were largely the work of H. Wild, but modifications have been subsequently made by others, especially M. Eschenhagen. Wild's form of instrument for field observations consists of a coil i o cm. in diameter containing about i,000 turns of silk-covered copper wire, with a resistance of about 40 ohms. The coil is pivoted inside a metal ring which can be rotated about a horizontal axle in its own plane, this axle being orthogonal to that about which the coil can rotate. Attached to the axle of the ring is a divided circle with two reading micro scopes by means of which readings can be taken of the inclina tion of the coil's axis of rotation to the horizontal. The bearings which support the horizontal axle of the ring are mounted on a horizontal annulus, which can be rotated in a groove attached to the base of the instrument, so as to allow the adjustment of the azimuth of the axle of the ring, and hence also that of the plane in which the axis of the coil can move. The coil is rotated by means of a flexible shaft, worked by a small cranked handle and a train of gear wheels. The terminals of the coil are taken to a two-part commutator of the ordinary pattern, on which rest two copper brushes, which are connected by flexible leads to a sen sitive galvanometer. The inclination of the axis of the coil can be roughly adjusted by hand by rotating the supporting ring. The final adjustment is made by means of a micrometer screw.The first thing when making an observation is to set the azimuth circle horizontal, checking this by a striding level placed on the trunnions which carry the ring. The striding level is then placed on the axle which carries the coil, and when the bubble is at the centre of the scale the microscopes are adjusted to the zeros of the vertical circle. A box containing a long com pass needle, and having two feet with inverted V's, is placed so as to rest in the axle of the coil, and the instrument is turned in azimuth until the compass needle points to a lubber line on the box. By this means the axis of the coil is brought into the mag netic meridian. The coil is then rotated, and the ring adjusted until the galvanometer needle is undeflected. The reading on the vertical circle then gives the dip. Slight faults in the adjustment are eliminated by a scheme of reversals analogous to that with the dip circle. The degree of accuracy claimed for the final value of the dip is -±- I', but a good deal depends on the judgment of the observer.

In the form of Wild inductor intended for observatory use the coil consists of a drum-wound armature, the length of which is about thrice the diameter. This armature has its axle mounted in a frame attached to the sloping side of a stone pillar, so that the axis of rotation is approximately parallel to the lines of force of the earth's field. The inclination of the axis to the magnetic meridian and to the horizontal can be adjusted by two micrometer screws. The armature is fitted with a commutator and a system of gear wheels by means of which it can be rapidly rotated. The upper end of the axle carries a plane mirror, the normal to which is adjusted parallel to the axis of rotation of the armature. A theodolite is placed on the top of the pillar, and the telescope is turned so that the image of the cross wires, seen by reflection in the mirror, coincides with the wires themselves. In this way the axis of the theodolite telescope is placed parallel to the axis of the armature, and hence the dip can be read off on the altitude scale of the theodolite.

A modified pattern of earth inductor with a suitable type of galvanometer has been devised by the department of terrestrial magnetism of the Carnegie Institution for taking dip observations at sea.

The primary object of dip observations at an observatory is to assist in determining the base value of the vertical force curves. Suppose a dip I has been observed with a dip circle or inductor at a certain time. The corresponding value of H is then derived by measuring the ordinate of the H curve, standardized by absolute measurements with the unifilar magnetometer V being simply H tan I is then known. Subtracting the force equivalent of the corresponding ordinate of the V curve from the value thus found for V, we have the base line value. If now A denote a small change in a magnetic element, we easily find L1I =1 sin 21 { (L1 V/V) — (AH/H) } . This shows that in high magnetic lati tudes where 21 approaches 18o°, and V is very large, a dip circle or inductor is an insensitive instrument to changes in V. It takes a very large change indeed in V to produce a change of even o'.1 in I. This has suggested the importance of devising coil instru ments to measure V directly. Instruments accomplishing this in two different ways have been devised by D. la Cour of Copen hagen and D. W. Dye of the National Physical Laboratory, Ted dington. The method followed by the latter is to reduce to zero the earth's vertical field by means of an artificial field produced by a current in a horizontal coil. The measurement of the current gives the strength of the artificial field, the coil constants being known, and hence the earth's vertical force.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-Admiralty

Manual of Scientific Enquiry; R. W. Bibliography.-Admiralty Manual of Scientific Enquiry; R. W. Fox, Annals of Electricity, iii. (1839), 288; H. Lloyd, Proc. Roy. Irish Acad. iv. (1848), 57; E. Leyst, Repertorium fur Meteorologie St. Petersburg, x. (1887), No. 5; B. Stewart and W. W. H. Gee, Elemen tary Practical Physics, vol. ii. (1888) ; E. Mascart, Traite de Mag netisme Terrestre; H. Wild, Repertorium fur Meteorologie, xvi. (1892), No. 2, and Met. Zeit. xii. , 41 ; L. A. Bauer, Terrestrial Mag netism, vi. (19o1) , 31 ; C. Chree, British Antarctic Expedition (1910 13) , Terrestrial Magnetism, s. 146 ; D. L. Hazard, Directions for Mag netic Measurements (1911) ; D. la Cour, Terrestrial Magnetism, xxxi. (1926), 153 ; D. W. Dye, Proc. Roy. Soc. (1927), A. 117, 434.(C. CUR.)