the Indian Desert

INDIAN DESERT, THE. Between the ancient Aravalli mountains and the wall-like front of the recently folded arcs which carry the Indo-Baluchistan frontier, and from the shores of the Arabian sea to within an average distance of c. 8o m. from the Himalayas, extends a lowland exceeding 200,000 sq.m., with an annual rainfall of less than 15 in. and a population of about 15 million. At one extremity it touches the northern tropic ; at the other it passes beyond 32° N. lat. It includes most of that part of the Punjab which constitutes "The Land of the Five Rivers," together with the adjoining trans-Indus districts of Dera Ghazi Khan and Dera Ismail Khan; the whole of Sind and, to the imme diate north, Kachhi (Kalat). The western hem of south-east Pun jab must be added also. Native States territory constitutes a solid block extending from the Sutlej-Indus line, east of Sind, to the Aravallis, including Bahawalpur (q.v.), and to the south the Raj putana States of Bikaner, Jaisalmer, and Jodhpur (qq.v.). Native territory touches the Indus again for a short distance below Sukkur where Khairpur State, hinging on to the west of Jaisalmer, breaks across Sind to the river. Finally Cutch State passes down from Jodhpur to the seaboard south of Sind.

A range of 10° of lat. implies considerable climatic diversity, and the area embraced leaves room for topographical variety. Yet it remains a major natural entity, the character of which is con veyed in the title "Arid Lowland." The tract has a general slope from the Himalayas to the Arabian sea, i.e., north-east to south west. Along its inner margin, in Punjab, the land between the rivers (doabs) rises to c. 700 ft.; but the western portions of the doabs and south of the Sutlej, almost all Bahawalpur, lie below the Soo ft. contour line. The 25o ft. contour line cuts the Indus river as it enters Sind, the heart of which province is well below this ; the rest, with the conspicuous exception of the Kohistan, not much above it. To the south-east towards the Aravallis, the low land attains a general level of over i,000 ft. whence it grades down north-westwards, i.e., traversing the prevailing slope at right angles. Except for a fringe of Jaisalmer, and the basin of the Luni river draining south-east to the Runn of Cutch, all Rajputana stands well above Soo f t. and betrays its physical "betweenness." Its deep mantle of aeolian deposits allies Rajputana superficially with the alluvial expanse upon which it encroaches. But it is not so completely destitute of solid rocks, and these, rising as low heights above the sandy surface, indicate a deep-seated unity with peninsular India as a coastal margin shelving from the Aravallis towards the seas, persisting to the north until late geological time.

Climate.

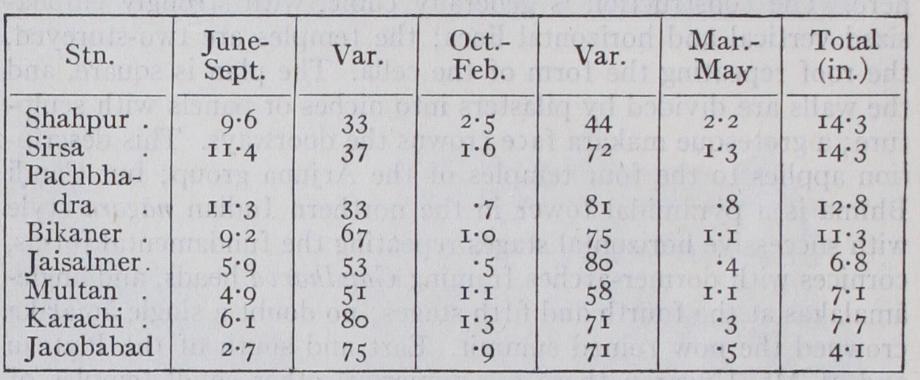

Climatically the tract is one of extreme tempera ture range, daily and seasonal. This is tempered somewhat along the coast but increasingly marked northwards. November to February is warm, with a mean daily temperature of F. The minimum falls in January. The designation "Cold Season," which is applied to this period (particularly the latter half), serves to emphasize the contrast with conditions prevailing during the rest of the year; namely, the low night temperatures with liability to frequent frost in the Punjab (Khushab mean min. Jan. 41.5° F, lowest recorded 25.0° F) and north Sind, though else where such occurrences are very rare; the limitation imposed upon agriculture by the exclusion of essentially tropical plants at this season; and, lastly, the relief, which its duration affords to Euro peans. Pressure is high in relation to the neighbouring seas, and only light winds blow from north-west and west. Except during the passage of shallow cyclones from across the North-West Fron tier, toward the south-east, bringing a little rain to the Punjab fringe (rarely elsewhere), cloud is absent. March to October is hot. From May to July the mean daily temperature exceeds 90° F, with the maximum in June. Afternoon readings of 11o° to 12o° F are registered (Jacobabad 127° June 1919; highest ever recorded in India). The rising temperature initiates a reversal in pressure and amid the changing conditions duststorms are generated.Winds from the west and south-west are well established by April and persist until October, blowing with increasing strength as the depression deepens over the land until they reach their final expression in the south-west monsoon proper. But the air currents now entering the lowland on this side emanate from the dry land belt about the head of the Arabian sea. Hence they are not sat urated like those, which, originating over a broad ocean, impinge on the Bombay coast but only "stray" just north of the Aravallis. They confer even scant benefit to the immediate coast fringe; beyond, they desiccate. Since also the Bay of Bengal branch of the advancing monsoon, which enters the lowland from the east on a downhill journey to its barometric goal, has already served the whole Gangetic plain, its remaining moisture is soon exhausted. Thus of the 213,110 sq.m. actually under review 47,590 receives less than 5 in. per annum; 95,56o 5 to 10 in., 69,96o 10 to 15 inches. The following illustrates briefly the salient features of distribution, and how precipitation shrinks north, south and east towards Upper Sind and Kachhi : Var. (variability) indicates departure from average seasonal rain fall as registered in half the years during 189o-1923, expressed in percentage. It is one way of illustrating the violently fluctuating regime. In general, March to May returns are insignificant.

Water.

It is a truism that natural boundaries are zonal not linear ; and generalizations concerning the biological effectiveness of rainfall are dangerous. Space forbids qualifications, yet it may be accepted that over the lowland precipitation is such that it pre cludes the transformation of the surface by permanent cultivation, and that over those parts which lie beyond the sphere of running water a desert landscape prevails. At once, therefore, it claims a continuous area of just over 1 oo,000 sq.m. cut off from effective water circulation. This involves Bikaner, with Jaisalmer and nearly all Jodhpur; Bahawalpur practically to the north-west rail way which runs parallel to the Sutlej ; the Runn of Cutch, and north of it as much of Thar and Parkar district (Sind), Khairpur State, and Sukkar district (Sind) as lie east of the Nara river (properly canal). Its name "Thar" refers to the sandhills accumu lated by the prevailing winds which transport thither the saline dust picked up over the Indus delta and the Runn. Two types of sandhills are recognized. (i) Longitudinal (Sindhi Bhits), parallel ridges aligned north-east south-west, i.e., parallel to the prevailing winds. The bhits are restricted to the west, i.e., Thar and Parkar south of Umarkst, eastwards to the Luni basin. They reflect greater wind force than (ii) Transverse type, to which they give way, through intermediate forms, north-east of Umarkst. These lie at right angles to the wind but are less regularly aligned than (i). The marginal dunes rise to about 200 ft. above the general sandy surface and are relatively permanent. Further inland they are lower, in constant motion, and the landscape tends towards a low plateau of deep, loose sand, reminiscent of a billowy sea.Deserted by a "westering" parent, the feeble monsoon streams which struggle across south-east Punjab, between the Sutlej and Jamna rivers, succumb before the sand ere the Rajputana border is reached. The Luni river is the only significant watercourse within the area. It receives several Aravalli streams from the south-east and is at least a support to the subsoil water within its bend ; but it loses itself in sand at the head of the Runn.

Salt.

The salinity of the soil, characteristic of the whole low land and here very marked, is sufficiently accounted for throughout Thar by the action of the wind, bringing material from the sea board. The evaporation of subsoil brine is common over Raj putana (particularly Pachbhadra neighbourhood) and also beyond south-west of Delhi, in Multan and Muzaffargarh. The Rajpu tana salt lakes, representing the fixation of salt washed into basins of internal drainage, are marginal to the desert. Of these, Sam bhar, on the Jodphur-Jaipur boundary is the largest. It lies in a closed depression in the Aravalli schists (1,184 ft.). Its maximum spread is 90 sq.m. and during a normal monsoon it averages 4 ft. deep in the middle, but is dry the greater part of the year. The upper 12 ft. alone of saliferous silt forming its bed represents a salt reserve of about 54,000,00o tons. The lake is worked on lease by the Government of India, and the salt extracted is railed to Sambhar at the eastern end of the lake, whence it is distributed (average annual yield 1918-19 to 1922-23, 230,340 tons). Lesser lakes, of scant importance, occur to the north-west.Gypsum, also occurring on the margins of some of the lakes, may prove more important in the future. In Sind and Khairpur, where the floor of alluvial clay remains uncovered or only thinly mantled with sand, shallow though often large expanses of water known as dhands are common in the hollows (talis) between the sandhills. They are fed by rain water percolating through the sand and emerging as a spring (sim) above the clay. Prior to the con trolling of the Nara river many dhands were replenished by its flood spills, but these have now mostly dried up. Sim water is often sweet, and gives rise to fresh pools close to where it emerges and lying a few feet above the dhand proper, which is either alkaline or saline, rarely fresh, its particular nature being recog nizable from its fringe of vegetation. All dhands shrink seriously after rain ; the smaller ones dry up. The mineral trona, from the alkaline dhands, supports the soda (cizaniho) industry of Khaipur State and Nawabshah district (Sind). Saline dhands yield salt and gypsum.

Flora.

A varied, open, shrubby and coarse herbaceous vege tation is characteristically present, salt lovers being conspicu ous. On sweet, damp bottoms, and after rain, good grass abounds. Thus fodder exists for large numbers of cattle, sheep, goats and camels ; villages are scattered everywhere.When rain is propitious, millets (principally bajra) are raised and husbanded to eke out a milk diet supplemented otherwise only by such imported grain as the profits of the pastoral industry and associated crafts, such as the making of blankets, felts, lohis (coarse shawls), ropes, bags, brushes and leather goods render possible. Typical desert talukas of Sind show a population density per square mile of less than 20 (cf. Diplo. 12; Chachro 18); Jaisalmer the "core" of the desert has an over-all density of 4 per sq.m. ; Bikaner gives 28 (Bikaner city 85,927) ; Jodhpur 53 (Jodh par city 94,736), but a heavy allowance must be made for that part of the State outside the essential desert. Roughly, Thar car ried c. 21 millions, largely marginal.

The Runn of Cutch

(Rann of Kachh), embracing c. 8,000 sq. m., while an integral part of the desert, possesses a distinctive character. It is a low-lying salt-impregnated alluvial tract. Seem ingly uniformly level, it has a general imperceptible slope seaward, while minor irregularities give shallow surface depressions. When the surface is dry it is hard and polished, "even a horse's hoof hardly dents it in passing." During the south-west monsoon, however, it is flooded by the waters of the Luni, Puran, Banas and other rivers assisted by rain remaining on the hard surface, but the view that at this season the sea invades it (the sea level is raised 4 to 5 ft.) has been disproved and abandoned. During flood the water varies in places from a few inches to some feet, but after it subsides evaporation proceeds until only salt remains.Lying in a belt liable to pronounced seismic disturbance, the Runn suffered severe displacement in 1819 ; depression increased the "rann" proper, but aeolian deposits have diminished it since. It is a range for wild asses. The impoverishment of the Runn and much of what is now Thar reflects the "westering" of the Indus and associated Punjab rivers. A map shows that the streams mak ing for Rajputana across the low Sutlej-Jumna watershed con verge towards a large dry water course (the Ghaggar), which runs parallel to the Sutlej and is traceable beyond through Sind to the Runn, roughly via the east Nara and Puran. This is the Hakra, or "Lost River," fed formerly by the Sutlej (possibly at one time by other Punjab rivers), and in its lower course (as the Mihran of Sind), by the Indus. Such was the known condition in the 8th century A.D. Subsequent probably to phenomenal flooding in north Punjab, placed in the 14th century, a rearrangement of drainage initiated the decline of the Hakra. First a "westering' Indus ceased to feed its lower reach; eventually the Sutlej completely deserted it and passed to the Indus via the Beas. By 1790 the Hakra was dead. The tapping by bunds of the waters latterly feeding the Puran from an Indus distributary assisted to complete the dereliction of the abandoned delta (the Runn).

Irrigation.

Outside Thar, the immediate valleys of the rivers sustained by the snows of Himalayas, tree-lined and recuperated by inundations, break the arid continuity, while as a result of irri gation achievement the desert survives only in fragments. Con sequent upon the melting snows, the Indus and rivers of Punjab begin to rise in March, and normally spill over the land in mid June. Floods culminate in August, and the rivers fall fairly rapidly to a minimum about February. From antiquity channels have been dug to utilize the rising waters. Such inundation canals are neces sarily restricted to the lower marginal lands, i.e., mainly newer alluvium (Khadar), which in Punjab lies io to So ft. below the older alluvium (Bhangar) comprising the doabs, and varies from 4 to Io m. wide. Hence they occur mainly where the "Five Rivers" converge to form the single artery continued in the line of the Indus, and attain their maximum development in Sind, where the widening Khadar merges into truly deltaic land. Many of these canals existed prior to British rule; they have been improved and others added. Since inundation canals function only during the floods and fluctuate with the natural level of the water in the river their shortcomings are obvious. Yet they play a big part. At present they are virtually the only form of irrigation in Sind, and they serve c. I Z million acres in the Punjab. Thus (average annual area irrigated 1923-24 to 1925-26, in acres) : Upper Sutlej canals, 320,237 ; Lower Sutlej canals, ; Indus Inundation, 945 ; Muzaffargarh Inundation, ; Chenab Inundation, 185, In addition, the Sutlej serves c. 900,00o ac. in Bahawalpur and there is a small canal in Dera Ismail Khan.

Agriculture.

It is, however, to the expansion of great peren nial systems over the broad backs of the Punjab doabs, and the development of model agricultural colonies thereon, that the elim ination of the desert between the Jhelum-Chenab on the one hand and the Sutlej on the other is due. Details of what this has meant must be omitted, but the following Punjab census (1921) return is noteworthy : "In 1891 the population density contour line, i oo per sq.m., which enclosed the oasis of Multan was no less than 16o m. distant from the general zoo per sq.m. density line. Since 1891, however, due to the development of the Lower Jhelum, Lower Chenab and Lower Bari doab canals the line has advanced at an average rate of c. 1 o m. per annum, and in 1911 Multan had been turned, from the point of view of population, from an island into a narrow-necked peninsula." Agriculturally it has meant the estab lishment of c. 1 million acres of acclimatized American upland cotton with a staple of c. 1 in., and a great wheat expansion.The following gives the area now being served ; canals marked* lie entirely in the arid zone, the others affect its margins (average annual acreage 1923-24 to 1925-26) : Lower Chenab*, 2,478,210; Lower Jhelum*, 868,064; Upper Jhelum, 326,786; Upper Bari doab ; Lower Bari doab* 1,165,109. The Sutlej valley project, now in hand, will convert certain inundation canals de pendent on that river into perennial, and assure the flood supply of the rest, while extending irrigation into the Bahawalpur and Bik aner fringes of Thar. When complete it will irrigate 5,108,00o ac., including 2,07 5,00o perennial and 2,033,00o non-perennial; 3 a mil lion acres at present waste, will be available for colonization. Rep resentation by the Bombay Government has led the Government of India to hold up further undertakings by Punjab pending in vestigations into Indus river supplies ; the position is difficult and a Central Indus Board is mooted.

Projects.

Punjab is anxious to carry out two big tasks at least. Firstly, to reclaim the Sind-Sagar doab by the Thal proj ect, which would carry water from the Indus at Kalabagh over Mianwali and Muzaffargarh above its inundated "tail." Secondly, to construct the Bhakra dam on the Sutlej where it emerges from the hills, with a canal to supplement the Sirhind and west Jumna canals (feeding 728,953 and 1,591,629 ac. respectively), and to extend irrigation in Hissar and Bikaner. This would give sorely needed protection to the arid skirt of south-east Punjab, at present served only by the lower reaches of the canals mentioned (assisted by the small Ghaggar inundation canals), and also nibble a little off east Thar.The recession of the western mountain wall enables the Indus, after receiving the united volume of the Punjab rivers, to enter Sind as a south-west flowing river. Near Schwan it turns south in the presence of the Laki range but manifests its "westering" tendency again in its final struggle seaward. The bifurcation of the Ochito and Haidari is quoted as the head of the delta; but, of course, throughout Sind the river is really deltaic, flowing on a ridge above the land on either side, restrained in parts by embank ments, but requiring more to curb its devastating moods, while the lower part of the province is riddled with its dead channels. Only in the gorge between Sukkur and Rohri, where it traverses a gap at the north extremity of low hills running for 4o m. south from its left bank, and in the Kotri neighbourhood is its channel con stant. Its sphere of influence, between the mountains on the west and Thar on the east, defines settled Sind. The cultivable area commanded by canals dependent on it approaches nine million acres of which, in 1924-25, 2,168,682 ac. were irrigated under the right bank systems and 1, 5 5 7, 201 under the left. As the Indus is not yet weir-controlled, technically all its irrigation is by inun dation, its canals functioning only during the flood season (June to early October) . One or two, however, receive a little water in the "cold" season, and the Jamrao canal, weir-controlled and fed from the east Nara supply channel (linked with the Indus but not weir-controlled itself), is truly perennial. In order to afford an assured supply at all times, the Sukkur Barrage project, after long years of discussion, has recently been undertaken. The barrage is to be placed 3 m. below the Sukkur gorge. Briefly, four canals will take off the left bank and three (one a purely rice canal) off the right bank. They will take up the area south of Sukkur at present under inundation irrigation, and in addition will enable a consid erable area of waste to be cultivated. Actually 62 million acres of cultivable land will be commanded, and it is hoped to feed 53 mil lion acres annually, of which two million represents existing inun dation irrigation to be given an assured supply. Of improved cotton alone 700,00o ac. per annum are anticipated. The project will take c. 4o years to complete, but big developments are expected in ten years' time.

Westwards beyond the sphere of the Indus, the desert landscape is at once established, and the irrigated patches of daman (clayey soil) created and sustained by flood torrents searing the mountain wall, only throw the naked hideousness of the limestone rampart into bolder relief.