Austenite

AUSTENITE Solid Solution.—Since the word solution ordinarily connotes a liquid, the term solid solution appears to be a contradiction of terms. The solid solution of iron and carbon is so important that it has been given a special name, austenite, in honour of the Eng lish metallurgist, Sir William Roberts-Austen. If any steel is homogenized by long heating at 1,13o° C, the temperature of maximum solubility of carbon in gamma iron, quenched so rapidly as to prevent changes on cooling, etched, and examined under the microscope it will look like a pure metal (Plate III., fig. 3); i.e., a series of abutting crystalline grains of uniform appear ance—saving the slight coring which may remain after insufficient anneal, or some surplus material insoluble under any conditions.

Thus the solid solution has some of the essential characteristics of a liquid solution—it is a uniform dispersion of atoms of one element amongst atoms of another, and the proportions may be anything within the limits of solubility. Austenite in fact is an aggregate of crystals of gamma iron ; iron atoms are arranged in the face centred cubic system, within which are tucked away the carbon atoms here and there inside the space lattice.

Decomposition of Austenite.

Another similarity between the solid solution austenite and such liquid solutions as salt in water is that the mutual solubility of carbon in iron, or iron in carbon, whichever appears to be the excess element, changes with lowering temperature, and the then insoluble substance crystal lizes out. Such changes can occur in the atomic arrangement in entirely solid metal. The latter is not a fixed and entirely rigid structure, except perhaps at absolute zero. The atoms, while they do not wander about at random, as in a liquid, are in a state of thermal agitation and are moving in small orbits or oscillating back and forth with more and more vigour as the temperature goes up. Under such circumstances considerable rearrangement may take place by interchange of position, or by stranger atoms slipping through the open spaces in the crystalline lattice. Such crystalline rearrangements generally occur in a reasonably small temperature interval, involve an evolution or absorption of heat, and are recorded on time-temperature or cooling curves.

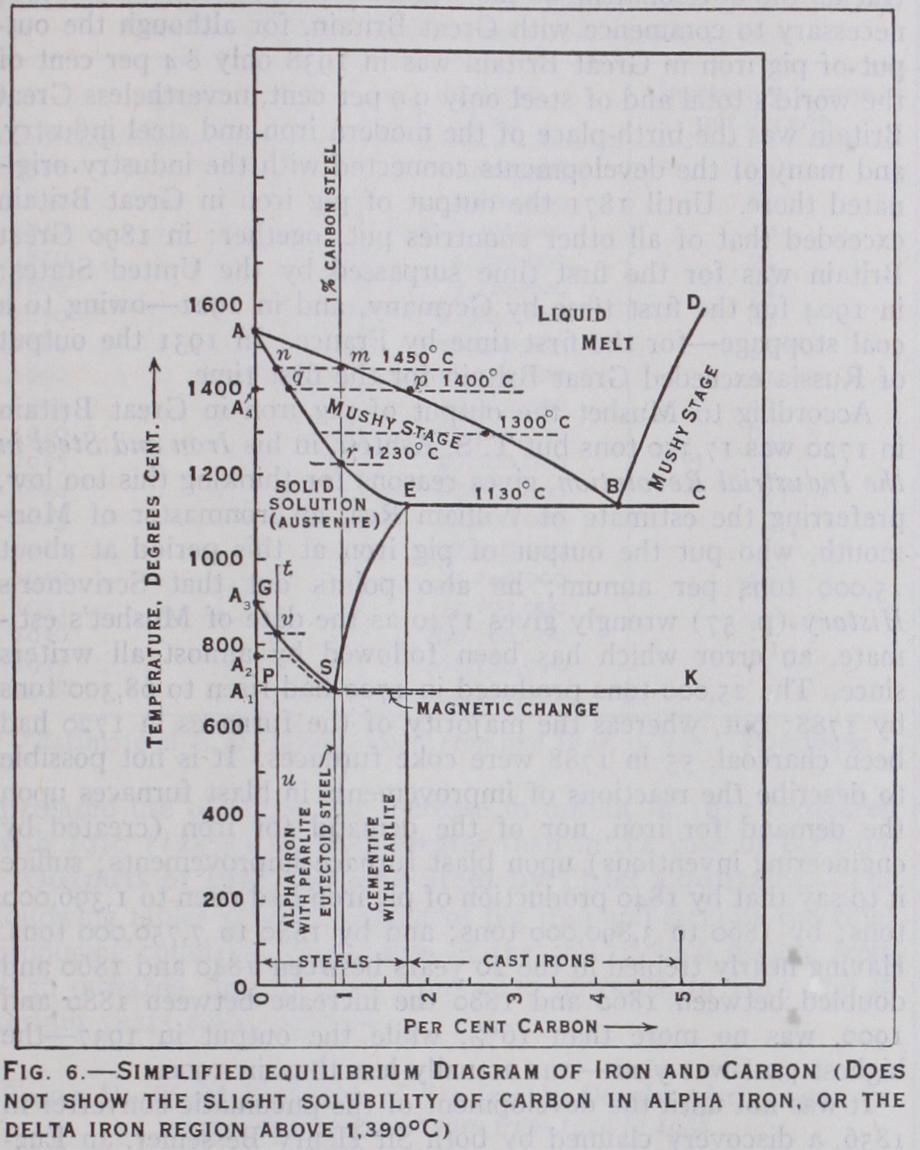

Cooling curves on a low carbon steel show that the change oc curring in pure iron at 91o° C from gamma to alpha form is lowered progressively with the increasing carbon content. Fur thermore a new and important evolution of heat occurs in all steels at about 69o° C, increasing in intensity as the carbon goes up. These two temperature arrests, called A3 and respectively, coincide at 0.9% carbon. At higher carbons two diverging tem perature effects are again noted. All these facts are noted on fig.

6, the steel end of the iron-carbon equilibrium diagram, by the lines GSE and PSK. This is an underlined V, a shape familiar to the physical chemist as noting the break up of a solution into two mutually insoluble constituents. In the case of steel, the solu tion is austenite; the excess constituent first precipitated out in low carbon steels is iron, or ferrite, while that first appearing in the highest carbon steels is not carbon but an iron carbide, called cementite. A 0.83% carbon steel corresponds to the eutectic. Since it appears in a solid solution it is termed a eutec toid. If examined under the microscope, a slowly cooled 0.83% carbon steel is made up of tiny flake-like crystals of iron and iron carbide, arranged in rough parallelism and having a pearly lustre.

Hence its name pearlite (Plate III., fig. 13). A cooling eutectoid steel reaching 69o° C is simultaneously saturated in both con stituents—they separate out simultaneously, side by side, in closely intermixed crystals.

Structure of Low Carbon Steels.

The mechanism may be illustrated by studying a cooling steel containing 0.25% carbon (line t u). Pure iron starts to be precipitated when the tempera ture reaches 82o° C (point v) and more and more pure iron crys tallizes out as the temperature falls, leaving a mother substance richer and richer in carbon. This action continues until at 690° C the remaining solid solution has reached saturation (point S, 0.83% carbon, the eutectoid) and that portion then rearranges itself into pearlite. Plate III., fig. 12 shows the microstructure at the end. The larger clear crystalline grains are alpha iron ; the gray specks are pearlite (high magnification is necessary to show the laminated structure). Medium carbon and hard steels have relatively less and less free ferrite, and more and more pearlite. A 0.83% carbon steel is all pearlite (Plate III., fig. 13). Slow cooled higher carbon steels (so-called "hyper-eutectoid" steels) have excess cementite in white veinlets surrounding pearlite masses (Plate III., fig. 2) Reverse changes to those described above take place on heating; that is, a well crystallized slowly cooled steel again reverts to a uniform solid solution when heated above the line GSE.

Structures in Quenched Steel.

The above described changes take place in a slowly cooled steel. If cooling is more rapid, time is not given for the atomic rearrangements necessary for such complete recrystallization, and certain intermediate microstruc tures may be observed. The most rapid quenching of austenite may be able to preserve this structure unchanged in the cold metal. In fact this can be done, especially in steels with consider able alloying elements like manganese or nickel. X-ray inves tigation of such a specimen of austenite proves that the metallic atoms build up a face-centred crystalline lattice characteristic of gamma iron. The carbon atoms are more or less uniformly dis tributed, but not combined in any definite compound. Such quenched manganese steels are exceedingly tough ; while they are not so hard as other steels under the Brinell test, it is impossible to cut them with a chisel ; they resist wear, scour, and impact well. High manganese steels are therefore suitable for such things as steam-shovel teeth and rail crossings.

High carbon steels, without alloys, can seldom be quenched rap idly enough to preserve very much pure austenite. Under the mi croscope a polished and etched surface appears to be criss-crossed with sharp needles (the lighter portions of Plate III., fig. 14). This structure has been given the name martensite ; it is the hard est and most brittle condition of steel. X-ray studies show that the iron has completely transformed into a body-centred tetrago nal crystalline lattice very similar to a lattice of alpha iron strained by trapped atoms of carbon ; it also indicates that the new crystals are exceedingly small, far below the ability of the microscope to see. The needle-like markings are relics of the larger austenite grains rather than actual structures of martensite.

At the interior of a quenched high carbon steel specimen, where the cooling rate is slightly slower than on the surface, the marten site needles may be mixed with rounded areas which etch much more rapidly, appearing black in fact. This structure is called primary troostite (also shown in Plate III., fig. 14) ; it also ap pears in a lower carbon steel rapidly quenched. Primary troostite is very fine pearlite; none of the individual crystals have grown to a point where they can be seen even at 5,000 magnifications ; however, the X-ray proves it to be an aggregate of excessively small crystals. Troostite, with hardness of 41 to 44 units on Rockwell "C" scale, is much softer than martensite (C-63 to C-65), but is noticeably less brittle.

Scientific studies since 1935 have shown that, while the tem perature of transformation of the austenite solid solution into pearlite is lowered somewhat from 69o° C as the rate of cooling is increased, and the result is finer and finer pearlite (primary troostite), this change in carbon and alloy steels always occurs at high temperatures—above 500° C. Time is required for the process, however, and if enough time is not given at those high temperatures during a rapid quench, then the austenite is retained unchanged to a low temperature, and transforms almost instantly into martensite (a solid solution of carbon in tetragonal ferrite) at 15o to oo° C. If carbon steels are quenched into a molten salt bath at some intermediate temperature, say 400° C, and held there long enough, the austenite leisurely transforms into another acicular microstructure whose exact nature is as yet un known. In carbon steels this intermediate structure has medium hardness and superior toughness. In some alloy steels the inter mediate structure appears during normal oil quenching, and its properties are not always so desirable.

If a quenched steel is moderately reheated (tempered or drawn) it loses a little of its hardness, but the added toughness is necessary for practical use. That is, tools are quenched and tempered. The microstructure is apparently unchanged, except that the acicular martensite etches much more rapidly. On re heating to higher and higher temperatures the atomic carbon first collects into submicroscopic crystals and the appearance under the microscope is uniformly structureless (secondary troostite), and later as the carbide crystals grow a cloudy microstructure, still unresolvable, appears and is called sorbite. If time and higher temperature below the transformation range (A1) is sufficient, tiny globules of carbide appear throughout the entire mass, a structure known as spheroidized cementite. This is the most easily machine able condition for high carbon steels.