Climate

CLIMATE The large extension of the Japanese islands in a northerly and southerly direction causes great varieties of climate. General characteristics are hot and humid though short summers, and long, cold and clear winters. The equatorial currents produce con ditions differing from those existing at corresponding latitudes on the neighbouring continent. In Kyushiu, Shikoku and the southern half of the main island, the months of July and August alone are marked by oppressive heat at the sea-level, while elevated districts a cool and even bracing temperature may always be found, though the direct rays of the sun retain distressing power. Winter in these districts does not last more than two months, from the end of December to the beginning of March; for, although the latter month is not free from frost and even snow, the balminess of spring makes itself plainly perceptible. In the northern half of the main island, in Yezo and in the Kuriles, the cold is severe during the winter, which lasts for at least four months, and snow falls sometimes to great depths. Whereas in TOkyo the number of frosty nights during a year does not average much over 6o, the corresponding number in Sapporo on the north-west of Yezo is 145. But the variation of the ther mometer in winter and summer being considerable—as much as 7 2 ° F in TOkyO—the climate proves somewhat trying to persons of weak constitution. On the other hand, the mean daily variation is in general less than that in other countries having the same latitude: it is greatest in January, when it reaches 18° F. and least in July, when it barely exceeds 9° F. The monthly variation is very great in March, when it usually reaches F.

Meteorology.—There are 19 meteorological stations in the Japanese dominions, including one at Dairen in South Manchuria and one at Paras in the mandated islands; and reports are con stantly forwarded from them by telegraph to the central observa tory in Tokyo, which issues daily statements of the climatic con ditions during the previous twenty-four hours, as well as f ore casts for the next twenty-four. The whole country is divided into districts for meteorological purposes, and storm-warnings ere is sued when necessary. At the most important stations observations are taken every hour ; at the less important, six observations daily; and at the least important, three observations. The following is a record of the mean annual temperature, which was in most cases a few fractions of a degree below the average, in 1926: F° Nemuro (HokkaidO) . 40•8 Hiroshima (Main Island) Sapporo (HokkaidO) . Kochi (Shikokes) . . 59.1 Aomori (HokkaidO) . 48.5 Nagasaki (KyOshii) . . 59.3 Tokyo (Main Island) . 56.4 Naha (Luchu Is.) . . 60.7 Niigata (Main Island) . 53.9 Seoul (Korea) . . . 51•I Nojano (Main Island) .50o Taipeh (Formosa) . . 60•7 Nagoya (Main Island) . 56.3 Odomari (Saghalin) . 36.8Kyoto (Main Island) . 55.9 Darien (S. Manchuria) . 50.3 Osaka (Main Island) . 58.4 Parao (Mandated Is.) . 80•2 Sakai (Main Island) . 56.8 Rainfall and Wind.—There are three wet seasons in Japan: the first, from the middle of April to the beginning of May; the second, from the middle of June to the beginning of July ; and the third, from early in September to early in October. The dog days (doy5) are from the middle of July till the second half of August. September is the wettest month ; January the driest. During the four months from November to February, inclusive, only about 18% of the whole rain for the year falls. In the dis trict on the east of the main island the snowfall is insignificant, seldom attaining a depth of more than four or five inches and generally melting in a few days, while bright, sunny skies are usual. But in the mountainous provinces of the interior and in those along the western coast, deep snow covers the ground throughout the whole winter, and the sky is usually wrapped in a veil of clouds. These differences are due to the action of the north westerly wind that blows over Japan from Siberia. The interven ing sea being comparatively warm, this wind arrives in Japan hav ing its temperature increased and carrying moisture which it de posits as snow on the western faces of the Japanese mountains. Crossing the mountains and descending their eastern slopes, the wind becomes less saturated and warmer, so that the formation of clouds ceases. Japan is emphatically a wet country so far as quantity of rainfall is concerned, the average for the whole coun try being 1,57o mm. per annum. Still there are about four sunny days for every three on which rain or snow falls, the actual figures being i so days of snow or rain and 215 days of sunshine.

During the cold season, which begins in October and ends in April, northerly and westerly winds prevail throughout Japan. They come from the adjacent continent of Asia, and they develop considerable strength owing to the fact that there is an average difference of some 22 mm. between the atmospheric pressure (750 mm.) in the Pacific and that (772 mm.) in the Japanese islands. But during the warm season, from May to September, these conditions of atmospheric pressure are reversed, that in the Pacific rising to 767 mm. and that in Japan falling to 75o mm. Hence throughout this season the prevailing winds are light breezes from the west and south. A calamitous atmospheric feature is the periodical arrival of storms called "typhoons" (Japanese tai-fu or "great wind"). These have their origin, for the most part, in the China sea, especially in the vicinity of Luzon. Their season is from June to October, September being generally the month when they are most frequent. But they occur in other months also, and they develop a velocity of 5 to 75 m. an hour. It is particularly unfortunate that September should be the season of greatest typhoon frequency, for the earlier varieties of rice flower in that month and a heavy storm does much damage not only to crops but also to life and property.

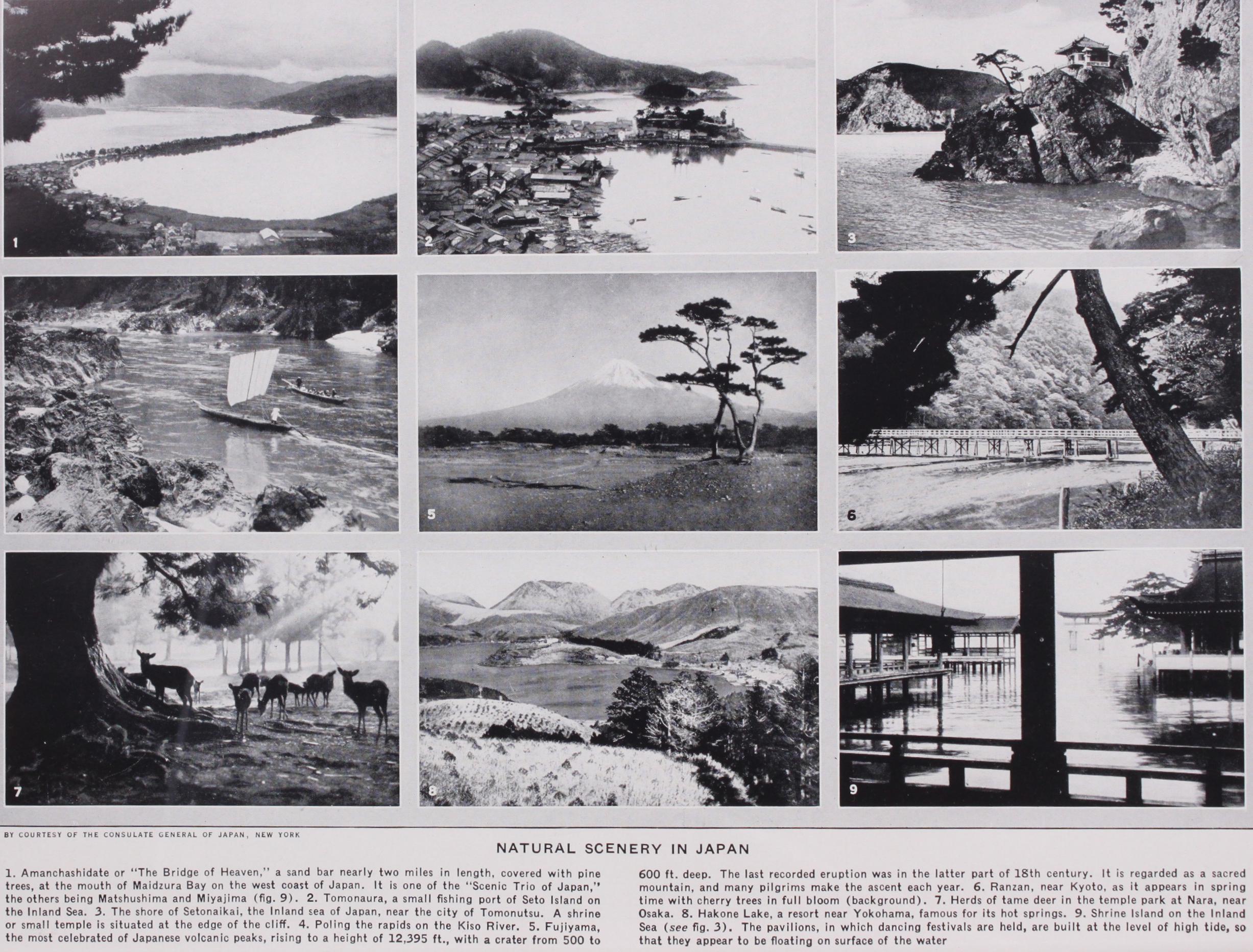

In actual wealth of blossom the Japanese islands cannot claim any special distinction. The spectacles most admired by all classes are the tints of the foliage in autumn and the glory of flowering trees in the spring. Oaks and wild prunus, wild vines and sumachs, various kinds of maple, the dodan (Enkianthus japo nicus Hook.), birches and other trees, all add multitudinous col ours to the brilliancy of a spectacle which is further enriched by masses of feathery bamboo. The one defect is lack of green sward. The grass used for Japanese lawns loses its verdure in autumn and remains from November to March a greyish-brown blot upon the scene. Spring is supposed to begin in February ; but the only flow ers then in bloom are the Camellia japonica, the narcissus, and some kinds of daphne. The first—called by the Japanese tsubaki —may often be seen glowing fiery red amid snow, but the pink (otome tsubaki), white (shiro-tsubaki) and variegated (shibori no-tsubaki) kinds do not bloom until March or April. The queen of spring flowers is the plum (ume), the pure white or rose-red blossoms of which are regarded with special favour and accounted the symbol of unassuming hardihood. The cherry (sakura) is even more esteemed. It will not suffer any training, nor does it, like the plum, improve by pruning; but the sunshine that attends its brief period of bloom in April, the magnificence of its flower-laden boughs and the picturesque flutter of its falling petals, inspired an ancient poet to liken it to the "soul of Yamato" (Japan), and it has ever since been thus regarded. The wild peach (momo) blooms at the same time, but attracts little attention. All these trees—the plum, the cherry and the peach—bear no fruit worthy of the name, nor do they excel their Occidental representatives in wealth of blossom ; but the admiring affection they inspire in Japan is unique. Scarcely has the cherry season passed when that of the wistaria (fuji) comes, followed by the azalea (tsutsuji) and the iris (shdbu), the last being almost contempora neous with the peony (botan), which is regarded by many Japanese as the king of flowers and is cultivated assiduously. Summer sees the lotus (renge) convert wide expanses of lake and river into sheets of white and red blossoms ; a comparatively flowerless interval ensues until, in October and November the chrysanthemum arrives to furnish an excuse for fashionable gatherings. With the exception of the dog-days and the dead of winter, there is no season when flowers cease to be an object of attention to the Japanese, nor does any class fail to participate in the sentiment. There is similar enthusiasm in the matter of gardens. From the loth century onwards the art of landscape gardening steadily grew into a science, with esoteric as well as exoteric aspects and with a special vocabulary. The underlying principle is to reproduce nature's scenic beauties, all the features being drawn to scale, so that however restricted the space, there shall be no violation of proportion. But it has to be clearly under stood that the flower-garden in the Occidental sense of the term scarcely exists in Japan. Flowers are cultivated, but for their own sakes, not as a feature of the landscape garden. If they are present, it is only as an incident. This of course does not apply to shrubs which blossom at their seasons and fall always into the general scheme of the landscape. There is another remarkable feature of the Japanese gardener's art. He dwarfs trees so that they remain measurable only by inches after their age has reached scores, even hundreds, of years, and the proportions of leaf, branch and stem are preserved with fidelity. The pots in which these wonders of patient skill are grown have to be themselves fine specimens of the keramist's craft, and hundreds of pounds are sometimes paid for a notably well trained tree.

There exists among many foreign observers an impression that Japan is comparatively poor in wild-flowers; an impression prob ably due to the fact that there are no flowery meadows or lanes. Besides, the flowers are curiously wanting in fragrance. Almost the only notable exceptions are the mokusei (Osmanthus fragrans), the daphne and the magnolia. But if some familiar European flowers are absent, they are replaced by others strange to Western eyes—a wealth of Lespedeza and lndigofera; a vast variety of lilies; graceful grasses like the eulalia and the ominameshi (Pa trina scabioesaefolia); the richly-hued Pyrus japonica; azaleas, diervillas and deutzias; the kikyo (Platycodon grandiflorum), the giboshi (Funkia ovata), and many another. The same is true of Japanese forests. It has been well said that "to enumerate the constituents and inhabitants of the Japanese mountain-forests would be to name at least half the entire flora." According to a statement in the Japan Year Book (1928) the flora of Japan con sists of about 17,087 species, classified as follows :—Flowering plants (9,000) ; Ferns (70o) ; Mosses (2,000) ; Fungi (3,50o) ; Lichens (70o) ; Marine algae (691) ; Fresh-water algae (323) ; and Mycetozoa (173).

While there can be no doubt that the luxuriance of Japan's flora is due to rich soil, to high temperature and to rainfall not only plentiful but well distributed over the whole year, the wealth and variety of her trees and shrubs must be largely the result of immigration. Japan has four insular chains which link her to the neighbouring continent. In the south, the Luchu Islands bring her within reach of Formosa and the Malayan archipelago; on the west, Oki, Iki, and Tsushima bridge the sea between her and Korea; on the north-west Sakhalin connects her with the Amur region; and on the north, the Kuriles form an almost continuous route to Kamstchatka. By these paths the germs of Asiatic plants were carried over to join the endemic flora of the country, and all found suitable homes amid greatly varying conditions of climate and physiography.

Japan is an exception to the general rule that continents are richer in fauna than are their neighbouring islands. It has been said with truth that "an industrious collector of beetles, butter flies, neuroptera, etc., finds a greater number of species in a cir cuit of some miles near Tokyo than are exhibited by the whole British Isles." Of mammals 5o species have been identified and catalogued. Neither the lion nor the tiger is found. The true Camivora are three only, the bear, the dog and the marten. The wolf is now extinct. Three species of bears are scientifically recognized, but one of them, the ice-bear (Ursus maritimus), is only an accidental visitor, carried down by the Arctic current. In the main island the black bear (kuma, Ursus japonicus) alone has its habitation, but the island of Yezo has the great brown bear (called shi-guma, oki-kuma or aka-kuma), the "grizzly" of North America. The bear does not attract much popular interest in Japan. Tradition centres rather in the fox (kitsune) and the badger (mujina), which are credited with supernatural powers. Next to these comes the monkey (saru), which dwells equally among the snows of the north and in the mountainous regions of the south. There are ten species of bat (komori) and seven of insect-eaters, and promi nent in this class are the mole (mugura) and the hedgehog (hari nezumi). There is a weasel (itachi), a river-otter (kawauso), and a sea-otter (rakko). The rodents are represented by an abun dance of rats, with comparatively few mice, and by the ordinary squirrel (ki-nezumi), as well as the flying squirrel (momodori, or bantori). There are no rabbits, but hares (usagi) are to be found in very varying numbers, and those of one species put on a white coat during winter. The wild boar (shishi or i-no-shishi) does not differ appreciably from its European congener. A very beautiful stag (shika), with eight-branched antlers, inhabits the remote woodlands, and there is a species of antelope (kamo shika) which is found in the highest and least accessible parts of the mountains. All the European domestic animals are also represented.

Although so-called singing birds exist in tolerable numbers, those worthy of the name of songster are few. Eminently first is a species of nightingale (uguisu), which, though smaller than its congener of the West, is gifted with exquisitely modulated flute like notes of considerable range. A variety of the cuckoo called hototogisu (Cuculus poliocephalus) in imitation of the sound of its voice, is heard as an accompaniment of the uguisu, and there are also three other species, the kakkodori (Cuculus canorus), the tsutsu-dori (C. himalayamcs), and the masuhakari, or juichi (C.

hyperythrus). To these the lark, hibari (Alauda japonica), joins its voice, and the cooing of the pigeon (hato) is supplemented by the twittering of the ubiquitous sparrow (suzume), while over all are heard the raucous caw of the raven (karasu) and the harsh scream of the kite (tombi). There are also several varieties of falcon ; but the eagle is comparatively rare. Two English ornithol ogists, Blakiston and Pryer, are the recognized authorities on the birds of Japan, and in a contribution to the Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan (vol. x.) they have enumerated 359 species. Starlings (muku-dori) are numerous, and so are the wag tail (sekirei), the swallow (tsubame) the martin (ten), the shrike (mozu) and the jay (kakesu or kashi-dori). Blackbirds and sing ing thrushes are absent ; the other members of the species Turdus are common. So too are the wren (miso-sazai), various kinds of finches (hiwa), and warblers (Kara) as well as the water-ouzel (kawagarasu), the wood-pecker (kitataki), the kingfisher (kawa semi), and the brown-eared bulbul (kiyodori). Among game-birds there are the quail uzura), the willow-grouse (ezo-raicho), the ptarmigan (raicho), the woodcock (hodoshigi), the snipe (ta shigi)—with two special species, the solitary snipe (yamashigi) and the painted snipe (tama-shigi)—and the pheasant (kiji). Of the last there are two species, the kiji proper, a bird presenting no re markable features, and the copper pheasant (yamadori), a magnif icent bird with plumage of dazzling beauty. Of cranes there are seven species, the Grus japonensis (tancho or tancho-zuru), the de moiselle crane (anewa-zuru), the black crane (kuro-zuru or nezurni zuru, i.e., Grus cinerea), the Grus leucauchen (mana-zuru), the Grus monachus (nabe-zuru), and the white crane (shiro-zuru). The little egret (shira-sagi) is a familiar feature of the Japanese land scape; so is the night-heron (goi-sagi). Besides these waders there are plover (chidori) ; golden (muna-guro or aiguro); gray (daizen); ringed (shiro-chidori) ; spur-winged (keri) and Harting's sand plover (ikaru-chidori) ; sand-pipers--green (ashiro-shigi) and spoon-billed (hera-shigi)—and water-hens (ban). Among swim ming birds the most numerous are the gull (kamome), of which many varieties are found; the cormorant (u)—which is trained by the Japanese for fishing purposes—and multitudinous flocks of wild-geese (gan) and wild-ducks (kamo), from the beautiful mandarin-duck (oshi-dori), to teal (kogamo), pintail (onaga); dusky mallard (karugamo), widgeon (akagashira) and sea-ducks of various species.

Of reptiles Japan has 90 species, and among them is included the marine turtle (umi-game) which is however seen only at rare intervals on the southern coast. Even rarer is the larger species (shogakubo, i.e., Chelonia cephalo). Both are highly valued for the sake of the shell. Of the fresh-water tortoise there are two kinds, the suppon (Trionyx japonica) and the kame-no-ko (Emys vulgaris japonica), one of the Japanese emblems of longevity.

Sea-snakes occasionally make their way to Japan, being carried thither by the Black Current (Kuro Shiwo) and the monsoon, but they must be regarded as merely fortuitous visitors. There are ro species of land-snakes (hebi), among which only two (the mamushi, or Trigonoceplialus blomhoffi) and the Labu are veno mous reptiles. The largest snake is the aodaisho (Elaphis virga tus), which sometimes attains a length of 5 ft., but is quite harm less. Lizards (tokage), frogs (kawazu or kaeru), toads (ebo gayeru) and newts (imori) are plentiful, and much curiosity at taches to a giant salamander (sansho-uwo, called also hazekai and other names according to localities), which reaches to a length of 5 ft., and (according to Rein) is closely related to the Andrias scheuchzeri of the Oeningen strata.

The seas surrounding the Japanese islands may be called a resort of fishes, for, in addition to numerous species which abide there permanently, there are migratory kinds, coming and going with the monsoons and with the great ocean streams that set to and from the shores. In winter, for example, when the northern monsoon begins to blow, numbers of denizens of the Sea of Okhotsk swim southward to the more genial waters of north Japan; and in summer the Indian Ocean and the Malayan archi pelago send to her southern coasts a crowd of emigrants which turn homeward again at the approach of winter. It thus falls out that in spite of the enormous quantity of fish consumed as food or used as fertilizers year after year by the Japanese, the seas remain as richly stocked as ever. Nine orders of fishes have been distinguished as the piscifauna of Japanese waters. They may be found carefully catalogued with all their included species in Rein's Japan, and highly interesting researches by Japanese physiographists are recorded in the Journal of the College of Science of the Imperial University of Tokyo. Briefly, the chief fish of Japan are the porgy (tai), the suzuki (Percalabeax japoni cus), the mullet (bora), the rock-fish (hatatate), the grunter (oni-o-koze), the mackerel (saba), the goby (kaze), the sword fish (tachi-uwo), the wrasse (kusabi), the cod-fish (ta,a), the flounder (karei), and its congeners the sole (Izirarne) and the turbot (ishi-garei), the shad (namazu), the salmon (shake), the masu, the carp (koi), the funa (Carassius auratus), the gold-fish (kingyo), the gold carp (higoi), the coach (dojo), the herring (nishin), the sardine (iwashi), the eel (unagi), the conger eel (anago), the coffer-fish (hako-uwo), the fugu (Tetrodon), the ayu (Plecoglossus altivelis), the sayori (Hemiramphus sayori), the shark (same), the dogfish (manuka-zame), the ray (e), the bonito (katsuo), the maguro (Thynnus sibi) and two forms of trout, the yamame and the iwana. The American brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) and the rainbow trout have been introduced from the United States.

The insect life of Japan broadly corresponds with that of temperate regions in Europe. But there are also a number of tropical species, notably among butterflies and beetles. The latter —for which the generic term in Japan is mushi or kaichis—in dude some beautiful species, from the "jewel beetle" (tama mushi), the "gold beetle" (kogane-mushi) and the Chrysochroa fulgidissima, which glow and sparkle with the brilliancy of gold and precious stones, to the jet black Melanauster chinensis, which seems to have been fashioned out of lacquer spotted with white. There is also a giant nasicornous beetle. Among butterflies (ch5cho) Rein gives prominence to the broad-winged kind (Pa pilio), which recall tropical brilliancy. One (Papilio macilentus) is peculiar to Japan. Many others seem to be practically identical with European species. That is especially true of the moths (yach5), loo species of which have been identified with English types. There are seven large silk-moths, of which two only (Bombyx more and Antheraea yama-mai) are employed in pro ducing silk. Fishing lines are manufactured from the cocoons of the genjiki-mushi (Caligula japonica), which is one of the commonest moths in the islands. Wasps, bees and hornets, generi cally known as hachi, differ little from their European types, except that they are somewhat larger and more sluggish. The gad-fly (abu), the housefly (hai), the mosquito (ka), the flea (nomi) and occasionally the bedbug (called by the Japanese kara mushi because it is believed to be imported from China) , are all fully represented, and the dragon-fly (tomb5) presents itself in immense numbers at certain seasons. Grasshoppers (batta) are abundant, and one kind (inago), which frequent the rice-fields when the cereal is ripening are caught and fried in oil as an article of food. On the moors in late summer the mantis (kama kiri-mushi) is commonly met with, and the cricket (kurogi), and the cockroach abound. Particularly obtrusive in the summer is the cicada (semi), of which there are many species. Spiders abound, from a giant species to one of the minutest dimensions, and ticks are very common in the long bamboo grass.

Japanese rivers and lakes are the habitation of several—seven or eight—species of freshwater crab (kani), which live in holes on the shore and emerge in the day-time, often moving to con siderable distances from their homes. Cray-fish (kawa-ebi) also are found in the rivers and rice-fields. These, as well as a large species of crab—mokuzo-gani—serve the people as an article of food; but the small crabs which live in holes have no recognized raison d' etre. In Japan, as elsewhere, the principal crustacea are found in the sea. Flocks of lupa and other species swim in the wake of the tropical fishes which move towards Japan at certain seasons. Naturally these migratory crabs are not limited to Japanese waters. Milne Edwards has identified ten species which occur in Australian seas also, and Rein mentions, as belonging to the same category, the "helmet-crab" or "horse-shoe crab" (kabuto-gani; Limulus longispina Hoeven). Very remarkable is the giant Taka-ashi—long legs (Macrocheirus kaempferi), which has legs r-1- metres long and is found in the seas of Japan and the Malay archipelago. There is no lobster on the coasts of Japan, but there are various species of cray-fish (Palinurus and Scyllarus) the principal of which, under the names of ise-ebi (Palinurus japonicus) and kuruma-ebi (Penaeus canaliculatus) are greatly prized as an article of diet.

Already in 1882, Dunker in his Index Molluscorum Maris Japonici enumerated nearly 1,200 species of marine molluscs found in the Japanese archipelago, and several others have since been added to the list. As for the land and fresh-water molluscs, some 200 of which are known, they are mainly kindred with those of China and Siberia, tropical and Indian forms being exceptional. There are 57 species of Helix (maimaitsuburi, dedemushi, katat sumuri or kwagyis) and 25 of Clausilia (kiseru-gai or pipe-snail), including the two largest snails in Japan, namely the Cl. mar tensi and the Cl. yokohamensis, which attain to a length of 58 mm. and 44 mm. respectively. The mussel (i-no-kai) is well represented by the species numa-gai (marsh-mussel), karasu-gai (raven-mussel), kamisori-gai (razor-mussel), shijimi-nokai (Cor bicula), of which there are nine species, etc. Unlike the land molluscs, the great majority of Japanese sea-molluscs are akin to those of the Indian Ocean and the Malay archipelago. Some of them extend westward as far as the Red Sea. The best known and most frequent forms are the asari (Tapes philippinarum), the hanuzguri (Meretrix lusoria), the baka (Mactral sulcataria), the aka-gai (Scapharca inflata), the kaki (oyster), the awabi (Haliotis japonica), the sazae (Turbo cornutus), the hora-gai (Tritonium tritonius), etc. Among the cephalopods several are of great value as articles of food, e.g., the surume (Onychotheu this banksii), the tako (octopus), the shidako (Eledone), the ika (Sepia), the tako-fune (Argonauta), and the Opistizoteuthis a remarkable flat octopus looking like a badly poached egg.

Greeff enumerates, as denizens of Japanese seas, 26 kinds of sea-urchins (gaze or uni) and 12 of starfish (hitode or tako-no makura). These, like the mollusca, indicate the influence of the Kuro Shiwo and the south-west monsoon, for they have close affinity with species found in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. For edible purposes the most valuable of the Japanese echinoderms is the sea-slug or beche de mer (namako), which is greatly appre ciated and forms an important staple of export to China.

Japan is not rich in corals and sponges. Her most interesting contributions are crust-corals (Gorgonidae, Corallium, Isis, etc.), and especially flint-sponges, called by the Japanese hoshi-gai and known as "glass-coral" (Hyalonema sieboldi). These last have not been found anywhere except at the entrance of the Bay of TOkyo at a depth of some 2oo fathoms.

Population.—The population of the Empire on the ist of October, 1930, when the last census was taken, was as follows :— According to the "Japan Year Book" the density of population, as shown by the census of 1925 was 6o.6 per sq. mile or 374.1 per sq. mile of cultivated area.

The following comparative tables may be of interest as show ing the rate at which the population has increased in recent years. It should be borne in mind that the term population in Japan proper includes all persons having registered domicile in Japan.

According to quasi-historical records, the population of the empire in the year A.D. 610 was 4,988,842, and in 736 it had grown to 8,631,770. It is impossible to say how much reliance may be placed on these figures, but from the 18th century, when the name of every subject had to be inscribed on the roll of a temple as a measure against his adoption of Christianity, a toler ably trustworthy census could always be taken. The returns thus obtained show that from the year 1723 until 1846 the popu lation remained almost stationary, the figure in the former year being 26,065,422, and that in the latter year 26,907,625. But after 1872, when the census showed a total of 33,110,825, the population grew steadily, its increment between 1872 and 1898, inclusive, a period of 27 years, being 10,649.990. The annual rate of increase is now estimated at something over 700,000, a figure which naturally invests the question of subsistence with great importance. It was hoped at one time that colonization in Man churia and Korea would materially help to solve the problem of over population; but the Japanese does not like extremes of climate, as is shown by the slowness with which the Hokkaido is being developed, nor does he thrive in countries, such as Man churia, in which the standard of living is lower than his own. Colonization therefore will not solve the population problem, nor will emigration, for reasons which it is unnecessary to discuss here. It is true that in Japan itself there is still a certain amount of waste land, probably about 5,000,00o acres, of which about 1,700,000 acres can be used for the cultivation of rice. The size of the crops can also be increased by the intensive use of fertil izers, and by these two methods the difficulties attending over population can be postponed for the moment. The question has already been the subject of discussion in many quarters, and Japanese authorities suggest three remedies,—(a) the expansion of industry, (b) the increase of the foreign trade, and (c) the advancement of agriculture. Birth-control is advocated in some quarters, but has not been seriously considered, nor is it likely to be. The birth-rate during the last 20 years has been about 3.05% of the population and the death-rate about 2.05%. Infant mortality is still heavy. The male birth-rate is about 4% in excess of the female. As compared with the inhabitants of Western Europe the Japanese are of low stature; but the rise in the standard of living and the cultivation of the physique in schools and colleges has resulted in a marked improvement in this direction in recent years.

Towns.—According to the figures of the census of 1930 there are in Japan 3o cities with a population of over ioo,000 inhabit ants. The only two cities with over a million are Tokyo with 4,970,839 and Osaka with 2,453,573. Kioto, Nagoya, Kobe and Yokohama come next with populations exceeding half a million.

The number of households in Japan proper when the census of 1930 was taken were 12,705,896 and the average number in each household was slightly over five.

Physical Characteristics.—The best authorities are agreed that the Japanese people do not differ physically from their Korean and Chinese neighbours as much as the inhabitants of northern Europe differ from those of southern Europe. It is true that the Japanese are shorter in stature than either the Chinese or the Koreans. Thus the average height of the Japanese male is only 5 feet 31 in., and that of the female 4 ft. 1o2 in., whereas in the case of the Koreans and the northern Chinese the corre sponding figures for males are 5 ft. 5-1 in. and 5 f t. 7 in., re spectively. Yet in other physical characteristics the Japanese, the Koreans and the Chinese resemble each other so closely that, under similar conditions as to costume and coiffure, no appre ciable difference is apparent. The late Dr. E. Baelz (Emeritus Professor of Medicine in the Imperial University of Tokyo), who made an exhaustive anthropological study of the Japanese, divides the race inhabiting the Japanese islands into three dis tinct types :—(a) Manchu-Korean, (b) Mongol, and (c) Malay or Indonesian.

The first is more common among the upper classes, and its characteristics are exceptional tallness combined with slenderness, a face somewhat long and having more or less oblique eyes, an aquiline nose, a slightly receding chin and delicately shaped hands. The most plausible hypothesis is that men of this type are de scendants of Korean colonists who, in prehistoric times, settled in the province of Izumo, on the west coast of Japan, having made their way thither from the Korean peninsula by the island of Oki. The second type is the Mongol. It is not very frequently found in Japan, perhaps because, under favourable social con ditions, it tends to pass into the Manchu-Korean type. Its repre sentative has a broad face, with prominent cheek-bones, oblique eyes, a nose more or less flat and a wide mouth. The figure is strongly and square built ; but this last characteristic can scarcely be called typical. There is no satisfactory theory as to the route by which the Mongols reached Japan, but it is scarcely possible to doubt that they found their way thither at one time. More im portant than either of these types as an element of the Japanese nation is the Malay or Indonesian. Small in stature, with a well knit frame, the cheek-bones prominent, the face generally round, the nose and neck short, a marked tendency to prognathism, the chest broad and well developed, the trunk long, the hands small and delicate—this type is found in nearly all the islands along the east coast of the Asiatic continent as well as in southern China and in the extreme south-west of the Korean peninsula. Carried northward by the warm current known as the Kuro Shiwo, this type seems to have landed in Kyushu—the most southerly of the main Japanese islands—whence it ultimately pushed northward and conquered its Manchu-Korean predecessors, the Izumo colo nists. None of the above three, however, can be regarded as the earliest settlers in Japan. Before them all was a tribe of immi grants who appear to have crossed from north-eastern Asia at an epoch when the sea had not yet dug broad channels between the continent and the adjacent islands. These people—the Ainu are usually spoken of as the aborigines of Japan. They once occupied the whole country, but were gradually driven north ward by the Manchu-Koreans and the Malays or Indonesians, until only a mere handful of them survived in the northern island of Yezo. Like the second and third types they are short and thickly built, but unlike either they have prominent brows, bushy locks, round deep-set eyes, long divergent lashes, straight noses and much hair on the face and the body. In short, the Ainu suggest much closer affinity with Europeans than does any other of the types that go to make up the population of Japan. It is not to be supposed, however, that these traces of different ele ments indicate any lack of homogeneity in the Japanese race. Amalgamation has been completely effected in the course of long centuries, and even the Ainu, though the small surviving remnant of them now live apart, have left distinct traces upon their conquerors.

The typical Japanese of the present day has certain marked physical peculiarities. In the first place, the ratio of the height of his head to the length of his body is greater than it is in Europeans. The Englishman's head is often one-eighth of the length of his body or even less, and in continental Europeans, as a rule, the ratio does not amount to one-seventh; but in the Japanese it exceeds the latter figure. Another striking feature is shortness of legs relatively to length of trunk. This special feature has been attributed to the Japanese habit of kneeling instead of sitting, but investigation shows that it is equally marked in the working classes who pass most of their time standing. In Europe the same physical traits—relative length of head and shortness of legs—distinguish the central race (Alpine) from the Teutonic, and seem to indicate an affinity between the former and the Mongols. It is in the face, however, that we find specially dis tinctive traits, namely, in the eyes, the eyelashes, the cheekbones and the beard. Not that the eyeball itself differs from that of an Occidental. The difference consists in the fact that "the socket of the eye is comparatively small and shallow, and the osseous ridges at the brows being little marked, the eye is less deeply set than in the European. In fact, seen in profile, forehead and upper lip often form an unbroken line." Then, again, the shape of the eye, as modelled by the lids, shows a striking peculiarity. For whereas. the open eye is almost invariably horizontal in the European, it is often oblique in the Japanese on account of the higher level of the upper corner. "But even apart from oblique ness, the shape of the corners is peculiar in the Mongolian eye. The inner corner is partly or entirely covered by a fold of the upper lid continuing more or less into the lower lid. This fold often covers also the whole free rim of the upper lid, so that the insertion of the eyelashes is hidden" and the opening between the lids is so narrowed as to disappear altogether at the moment of laughter. As for the eye-lashes, not only are they comparatively short and sparse, but also they converge instead of diverging, so that whereas in a European the free ends of the lashes are further distant from each other than their roots, in a Japanese they are nearer together. Prominence of cheekbones is another special feature ; but it is much commoner in the lower than in the upper classes. Finally, there is marked paucity of hair on the face of the average Japanese—apart from the Ainu—and what hair there is is nearly always straight.

Moral Characteristics.—The Japanese are essentially a kindly-hearted, laughter-loving people, taking life easily and not allowing its petty ills unnecessarily to disturb their equanimity. Suicide is, it is true, by no means uncommon; but by far its most frequent victims are students and lovers. The latter take refuge in it because circumstances prevent their being united in this world, and they go therefore to what they believe to be a union beyond the grave; in the case of the students the cause is generally to be found in the stress of modern conditions and the unduly heavy mental and physical strain imposed upon them by the existing system of education. Neither of these types, how ever, is normal ; and the average Japanese, while lacking that sense of humour which is conspicuous among some other races, is nevertheless a light-hearted and buoyant individual. It is rare to see a grown-up person, particularly among the educated classes, indulge in displays of temper. The Japanese is imperturbable in the face of provocation or trouble and, as a rule, completely stoical in the face of pain or death. This faculty of self-control is in a sense hereditary, the result of long centuries of rigid train ing and example. It has also been driven into him that personal cowardice is the most despicable of vices and loyalty, particularly loyalty to the Throne and to his country, the supreme virtue. The finished product of these teachings is a person imbued with a pride of race and a patriotism so intense that it not infrequently verges on fanaticism. There is a limit, too, to imperturbability, and when that limit is reached the resulting passion is corre spondingly violent. It will therefore easily be realized from this description of the Japanese character how formidable are the potentialities of this people as an enemy. Kaempfer, that most acute of observers, wrote of the Japanese that "their pride and warlike humour being set aside," they are "as civil, as polite and as curious a nation as any in the world, naturally inclined to commerce and familiarity with foreigners, and desirous, to excess, to be informed of their histories, arts and sciences," and what Kaempfer wrote in the Dutch factory at Nagasaki more than 200 years ago is almost equally true to-day. Contact with a ruder outside world may perchance since have blunted a little the fine edge of the national courtesy; but, if so, it is hardly perceptible; the intellectual curiosity to which he refers remains as strong as ever. Pride of race can naturally be carried to excess, and there have not been wanting critics, not necessarily biassed, to charge the Japanese with excessive self-confidence and self esteem ; others too have noted a certain fickleness of temperament, a tendency to quick enthusiasms easily dropped, and considerable secretiveness. But no nation is free from failings, and when due account has been taken of those of the Japanese, there still re mains a people of remarkable energy and intelligence, of mar vellous achievement, and of great attractiveness. It must not be inferred from the remark made above with regard to suicide among lovers that love as a prelude to marriage plays an impor tant part in Japanese ethics. As a matter of fact in the vast majority of cases marriages are arranged by the parents or in the family councils of the parties concerned without any par ticular regard to the feelings of the two people most directly interested. It might be supposed that conjugal fidelity would suffer from such a custom, and in the case of the husband it undoubtedly does ; but in the case of the wife it emphatically does not. Even though she be cognizant—as she often is—of her husband's extra-marital relations, she abates nothing of the duty which she has been taught to regard as the first canon of female ethics. From many points of view, indeed, there is no more beautiful type of character than that of the Japanese woman. She is entirely unselfish; exquisitely modest without being any thing of a prude ; abounding in intelligence which is never ob scured by egoism; patient in the hour of suffering; strong in time of affliction ; a faithful wife ; a loving mother ; a good daughter; and capable, as history shows, of heroism rivalling that of the stronger sex. As to the question of sexual virtue and morality in Japan, grounds for a conclusive verdict are hard to find. In the interests of hygiene prostitution is licensed, and that fact is by many critics construed as proof of tolerance ; but licensing is associated with strict segregation, and the result is that the great cities are conspicuously free from evidences of vice. The ratio of marriages is approximately 8.31 per thousand units of the population, and the ratio of divorces is 0.83 per thousand. Divorces take place chiefly among the lower orders, who frequently treat marriage merely as a test of a couple's suitability to be helpmates in the struggles of life.

Concerning the virtues of truth and probity, extremely con flicting opinions have been expressed. The Japanese samurai always prided himself on having "no second word." He never drew his sword without using it ; he never gave his word without keeping it. Yet it may be doubted whether the value attached in Japan to the abstract quality, truth, is as high as the value attached to it in England, or whether the consciousness of having told a falsehood weighs as heavily on the heart. Much depends upon the motive. Whatever may be said of the upper class, it is probably true that the average Japanese will not sacrifice ex pediency on the altar of truth. He will be veracious only so long as the consequences are not seriously injurious. In the matter of probity, however, it is possible to speak with more assurance. There are undoubtedly among the merchants and tradesmen a large number of persons whose standard of commercial morality is defective. They are relics of the feudal days when the mer chant and the tradesman, being despised, lost their self-respect. But this blemish is in gradual process of correction, and there are now many merchant houses in Japan which maintain as high a standard of probity as can be found anywhere.

There is no reliable information regarding the state of com munications in very early times in Japan; but in the Taika period (A.D. 645-650, the first great era of Japanese reform, a system of post-stations was established, provision was made for post horses along the great roads, which doubtless has long been in existence in the more populous districts, and a system of bells and checks was devised for distinguishing official carriers. In those days ordinary travellers were required to carry passports, nor had they any share in the benefits of the official organization, which was entirely under the control of the minister of war. Great difficulties attended the movements of private persons. Even the task of transmitting to the central government provincial taxes paid in kind had to be discharged by specially organized parties, and this journey from the north-eastern districts to the capital generally occupied three months. Owing to the anarchy which prevailed during the loth, iith and i 2th centuries, facilities of communication disappeared almost entirely; even for men of rank a long journey involved danger of starvation or fatal ex posure, and the pains and perils of travel became a household word among the people. Not until the Tokugawa family obtained military control of the whole empire (1603), and, fixing its capital at Yedo, required the feudal chiefs to reside there every second year, did the problem of roads and post-stations force itself once more on official attention. Regulations were now strictly enforced, fixing the number of horses and carriers available at each station, the loads to be carried by them and their charges, as well as the transport services that each feudal chief was entitled to demand and the fees he had to pay in return. Tolerable hostelries now came into existence ; but they furnished only shelter, fuel and the coarsest kind of food. By degrees, however, the progresses of the feudal chiefs to and from Yedo, which at first were simple and economical, developed features of competitive magnificence, and the importance of good roads and suitable accommodation re ceived increased attention.

It is not too much to say, indeed, that when Japan opened her doors to foreigners in the middle of the i9th century, she pos sessed a system of roads, some of which bore a striking testimony to her mediaeval greatness. The most remarkable was the Tokaido (eastern-sea way), so called because it ran eastward along the coast from KiOto. This great highway, 345 m. long, connected Osaka and KiOto with Yedo. The date of its construction is not recorded ; but it certainly underwent signal improvement in the I 2th and 13th centuries, and during the two and a half centuries of Tokugawa sway in Yedo. A wide, well-made and well-kept avenue, it was lined throughout the greater part of its length by giant pine-trees, rendering it the most picturesque highway in the world. Second only to the Takaido is the NakasendO (mid mountain road), which also was constructed to join KiOto with Yedo, but follows an inland course through the provinces of Yamashiro, Omi, Mino, Shinshu, Katzuke and Musashi. Its length is 34o m., and though not flanked by trees or possessing so good a bed as the TokaidO, it is nevertheless a sufficiently re markable highway. A third road, the OshilkaidO, runs northward from Yedo (now TokyO) to Aomori on the extreme north of the main island, a distance of 445 m., and several lesser highways give access to other regions.

Modern Superintendence of Roads.

The question of road superintendence received early attention from the government of the restoration. At a general assembly of local prefects held at Tokyo in June 1875 it was decided to classify the different roads throughout the empire, and to determine the several sources from which the sums necessary for their maintenance and repair should be drawn. As a result of the discussions which then took place it was decided that all roads should be divided into three classes: --national, prefectural and village—and that the first should be maintained at the national expense, the second by joint contribu tions from the government and the particular prefecture con cerned, and the third by the districts through which the roads ran. The width of national roads was determined at 42 ft. for class 1, 36 ft. for class 2 and 3o ft. for class 3; the prefectural roads were to be from 24 to 3o ft., and the dimensions of the village roads were optional, according to the necessity of the case.

Vehicles.

The vehicles chiefly employed in ante-Meiji days were ox-carriages, norimono, kago and carts drawn by hand. Ox carriages, beautifully made and decorated, were used only by people of the highest rank. The norimono resembled a miniature house slung by its roof-ridge from a massive pole which projected at either end sufficiently to admit the shoulders of a carrier. It, too, was frequently of very ornamental nature and served to carry aristocrats or officials of high position. The kago was the humblest of all conveyances recognized as usable by the upper classes. It was an open palanquin, V-shaped in cross section, slung from a pole which rested on the shoulders of two bearers. Extraor dinary skill and endurance were shown by the men who carried the norimono and the kago; but none the less these vehicles were both profoundly uncomfortable. They have now been relegated to the warehouses of undertakers, where they serve as bearers for folks too poor to employ catafalques, their place on the roads and in the streets having been completely taken by the jinrikisha, a two-wheeled vehicle pulled by one or two men who think nothing of running 20 m. at the rate of 6 m. an hour. The jinrikisha is, however, fast disappearing and its place is being taken, both in the towns and in the country, by the motor-car, though it must be confessed that Japanese roads are not yet by any means suitable for motor traffic. Luggage, of course, could not be carried by norimono or kago. It was necessary to have recourse to pack men, packhorses or baggage-carts drawn by men or horses. All these still exist and are as useful as ever within certain limits. In the cities and towns horses used as beasts of burden are now shod with iron, but in rural or mountainous districts straw shoes are substituted, a device which enables the animals to traverse rocky or precipitous roads with safety.

Railways.

It is easy to understand that an enterprise like railway construction, requiring a great outlay of capital with returns long delayed, did not at first commend itself to the Jap anese, who were almost entirely ignorant of co-operation as a factor of business organization. Moreover, long habituated to snail-like modes of travel, the people did not rapidly appreciate the celerity of the locomotive. Neither the ox-cart, the norimono, nor the kago covered a daily distance of over 20 m. on the average, and the packhorse was even slower. Amid such conditions the idea of railways would have been slow to germinate had not a catastrophe furnished some impetus. In 1869, a rice-famine occurred in the southern island, Kyfisha, and while the cereal was procurable abundantly in the northern provinces, people in the south perished of hunger owing to lack of transport facilities. Sir Harry Parkes, British representative in Tokyo, seized this occasion to urge the construction of railways. Ito and Okuma, then influential members of the government, at once recognized the wisdom of his advice. Arrangements were made for a loan of a million sterling in London on the security of the customs revenue, and English engineers were engaged to lay a line be tween Tokyo and Yokohama (18 m.) Vehement voices of opposi tion were at once raised in private and official circles alike, all persons engaged in transport business imagined themselves threat ened with ruin, and conservative patriots detected loss of national independence in a foreign loan. So fierce was the antagonism that the military authorities refused to permit operations of survey in the southern suburb of TOkyO, and the road had to be laid on an embankment constructed in the sea. Ito and Okuma, how ever, never flinched, and they were ably supported by Marquis M. Inouye and M. Mayejima.

September 1872 saw the first official opening of a railway (the Tokyo-Yokohama line) in Japan, the ceremony being performed by the emperor himself, a measure which effectually silenced all further opposition. Eight years from the time of turning the first sod saw 71 m. of road open to traffic, the northern section being that between 'Faye, and Yokohama, and the southern that be tween Kyoto and Kobe. A period of interruption now ensued, owing to domestic troubles and foreign complications, and when, in 1878, the government was able to devote attention once again to railway problems, it found the treasury empty. Then for the first time a public works loan was floated in the home market, and about £300,000 of the total thus obtained passed into the hands of the railway bureau, which at once undertook the building of a road from Kyoto to the shore of Lake Biwa, a work memorable as the first line built in Japan without foreign assistance, save for advisers. During all this time private enter prise had remained wholly inactive in the matter of railways, and it became a matter of importance to rouse the people from this apathetic attitude. For the ordinary process of organizing a joint-stock company and raising share-capital the nation was not yet prepared. But shortly after the abolition of feudalism there had come into the possession of the former feudatories state loan bonds amounting to some 18 millions sterling, which represented the sum granted by the treasury in commutation of the revenues formerly accruing to these men from their fiefs. Already events had shown that the feudatories, quite devoid of business ex perience, were not unlikely to dispose of these bonds and devote the proceeds to unsound enterprises. Prince Iwakura, one of the leaders of the Meiji statesmen, persuaded the feudatories to employ a part of the bonds as capital for railway construction, and thus the first private railway company was formed in Japan under the name Nippon tetsudo kaisha (Japan railway company), the treasury guaranteeing 8% on the paid-up capital for a period of 15 years. Some time elapsed before this example found fol lowers, but ultimately a programme was elaborated and carried out having for its basis a grand trunk line extending the whole length of the main island from Aomori on the north to Shimono seki on the south, a distance of 1,153 m. ; and a continuation of the same line throughout the length of the southern isiand of Kyushu, from Moji on the north—which lies on the opposite side of the strait from Shimonoseki—to Kagoshima on the south, a distance of 2324 m.; as well as a line from Moji to Nagasaki, a distance of 1631 m. Of this main road the state undertook to build the central section (376 m.), between TOkyo and Kobe (via Kyoto) ; the Japan railway company undertook the portion (457 m.) northward of TOkyo to Aomori; the Sanyo railway company undertook the portion (320 m.) southward of Tokyo to Shimono seki; and the Kyushu railway company undertook the lines in Kyilshil The first project was to carry the TOkyo-Kyato line through the interior of the island so as to secure it against enter prises on the part of a maritime enemy. Such engineering difficul ties presented themselves, however, that the coast route was ultimately chosen, and though the line through the interior was subsequently constructed, strategical considerations were not allowed completely to govern its direction.

When this building of railways began in Japan, much discussion was taking place in England and India as to the relative ad vantages of the wide and narrow gauges, and so strongly did the arguments in favour of the latter appeal to the English advisers of the Japanese government that the metre gauge was chosen. Some fitful efforts made in later years to change the system proved unsuccessful. The lines are single, for the most part ; and as the embankments, the cuttings, the culverts and the bridge piers have not been constructed for a double line, any change now would be very costly. The average speed of passenger trains in Japan is 18 m. an hour, the corresponding figure over the metre-gauge roads in India being 16 m., and the figure for English parliamentary trains from 19 to 28 m. British engineers surveyed the routes for the first lines and superintended the work of con struction, but within a few years the Japanese were able to dis pense with foreign aid altogether, both in building and operating their railways. They also now construct carriages, wagons and locomotives, and therefore are entirely independent in the matter of railway construction.

Nationalization of Private Railways.

The total length of lines open for traffic in March 1906 was 4,746 m. Of these 1,470 m. had been built by the State at a cost of sixteen million pounds sterling, and 3,276 m. by private companies at a cost of twenty five millions. The difference in cost is explained by the fact that the state lines frequently ran through very difficult country and that portions of them were built before experience indicated cheaper methods. Private companies, coming later into the field, naturally avoided districts presenting great engineering difficulties, and had the additional advantage of being able to profit from the experience bought at a price by the state. When the fiscal year 1906-07 opened, the number of private companies was no less than 36, owning and operating 3,276 m. of railway. Anything like efficient co-operation, an important matter in time of war, was impossible in such circumstances, and constant complaints were heard about delays in transit and undue expense. The de fects of divided ownership had long suggested the expediency of nationalization; but not until 1906 could the Diet be induced to give its consent. On March 31 of that year, a railway nationaliza tion law was promulgated. It enacted that, within a period of io years from 1906 to 1915, the state should purchase the 17 prin cipal private roads, which had a length of 2,812 m., and whose cost of construction and equipment had been 231 millions sterling. The original scheme included 15 other railways, with an aggregate mileage of only 353 m. ; but these were eliminated as being lines of local interest only. The actual purchase price of the 17 lines was calculated at 43 millions sterling (about double their cost price), and the Government agreed to hand over the purchase money within 5 years from the date of the acquisition of the lines, in public loan-bonds bearing 5% interest calculated at their face value; the bonds to be redeemed out of the net profits accruing from the purchased railways. The accounts for the state railways figure as a separate account independent of the budget.

South Manchuria Railways.

As a result of the war of 1904-05 Japan, with the acquiescence of China, took over from Russia the lease of the portion of the Chinese Eastern Railway between Kwang-cheng-tzu (Changchun) in the north and Dairen (Dalny), Port Arthur and Newchwang in the south. China at the same time agreed to lease to Japan the line between Mukden and Antung, which the latter had laid temporarily for military purposes during the war, but now proposed to convert into an ordinary commercial railway. A company called the South Man churia Railway was formed with a capital of 20 million yen, half of which was contributed by the Japanese Government in the shape of the road itself and its associated properties, the other half thrown open for subscription to Japanese and Chinese sub jects, and to it the railway was handed over. Debentures, the interest on which was guaranteed by the Japanese Government, were also issued in London to the amount of 8 million pounds sterling. The capital has since been raised to 44 million pounds and the amount of debentures increased till they now stand at 22 million. The total length of the railway with its various branches is 693 miles. The company's activities are not limited to its lines only. It works extensive coal mines at Fushun and Yentai, has a line of steamers plying between Dairen and Shanghai and an iron foundry at Anshan, and engages in enterprises con nected with warehousing, electricity, hotels, hospitals, schools and the general management of houses and lands within the rail way zone. Under the terms of a treaty made with China in 1915 the lease of the Changchun-Dairen section has been extended to A.D. 2002 and that of the Mukden-Antung section to A.D. 2007. Construction work has been well maintained since 1907 when nationalization took place. In 1917 the total railway mileage was 7,690 m., of which 5,856 m. represented State railways and m. private lines. In 1927 the total was 10,884 m., of which m. were state-owned and 3,047 m. the property of private com panies. No recent figures are available of the cost of construc tion of state lines; but the total given in 1927 for the private lines was close on 4o million pounds sterling. The total receipts in that year for both state and private lines from passenger traffic was over 26 million pounds and from freight 22 millions.

Electric Railways.—The first electric railway in Japan was a short one, 8 miles long, built in Kyoto for the purposes of a domestic exhibition held in that city. This class of enterprise has since rapidly grown in favour, and in 1926 io8, belonging either to municipalities or private companies, were in operation. Their total authorized capital is estimated at about i68 million pounds, their net earnings in 1926 about 14 million pounds, and the number of passengers carried about 18 hundred millions. Dividends varied from 7 to 14 per cent.

Maritime Communications.—The traditional story of pre historic Japan indicates that the first recorded emperor was an over-sea invader, whose followers must therefore have pos sessed some knowledge of ship-building and navigation, and historical records in fact show that the Japanese of the earliest era navigated the high sea with some skill. At later dates down to mediaeval times they are found occasionally sending forces to Korea and constantly visiting China in vessels which seem to have experienced no difficulty in making the voyage, while in the 16th century maritime activity was so marked that, had not artificial checks been applied, the Japanese, in all probability, would have , obtained partial command of Far-Eastern waters. They invaded Korea; their corsairs harried the coast of China; two hundred of their vessels, sailing under authority of the Taiko's vermilion seal, visited Siam, Luzon, Cochin China and Annam, and they built ships in European style which crossed the Pacific to Acapulco. But this spirit of adventure was chilled at the close of the 16th century and early in the 17th, when events connected with the propagation of Christianity taught the Jap anese to believe that national safety could not be secured without international isolation. In 1638 the ports were closed to all foreign ships except those flying the flag of Holland or of China, and a strictly enforced edict forbade the building of any vessel having a capacity of more than soo koku (15o tons) or constructed for purposes of ocean navigation. Thenceforth, with rare exceptions, Japanese craft confined themselves to the coastwise trade. Ocean going enterprise ceased altogether.

Things remained thus until the middle of the 19th century, when a growing knowledge of the conditions existing in the West warned the Tokugawa administration that continued isolation would be suicidal. In 1853 the law prohibiting the construction of sea-going ships was revoked and the Yedo government built at Uraga a sailing vessel of European type aptly called the "Phoenix" ("Hoo Maru"). In the same year Commodore Perry made his appearance, and thenceforth everything conspired to push Japan along the new path. The Dutch, who had been proxi mately responsible for the adoption of the seclusion policy in the 17th century, now took a prominent part in promoting a liberal view. They sent to the Tokugawa a present of a man-of-war and urged the vital necessity of equipping the country with a navy. Then followed the establishment of a naval college at Tsukiji in Yedo, the building of iron-works at Nagasaki, and the construction at Yokosuka of a dockyard destined to become one of the greatest enterprises of its kind in the East. The policy thus initiated by the Tokugawa was continued with increased energy after their downfall in 1867 and the restoration of the emperor to real power.

The various maritime carriers which had come into existence were made to amalgamate into one association called the Nippon koku yubin jokisen kaisha (Mail SS. Company of Japan), to which were transferred, free of charge, the steamers, previously the property of the Tokugawa or the feudatories, and a substantial subsidy was granted by the state. This, the first steamship com pany ever organized in Japan remained in existence only four years. Defective management and incapacity to compete with foreign-owned vessels plying between the open ports caused its downfall (1875). Already, however, an independent company had appeared upon the scene. Organized and controlled by a man (Iwasaki Yataro) of exceptional enterprise and business faculty, this Mitsubishi kaisha (three diamonds company, so called from the design on its flag), working with steamers char tered from the former feudatory of Tosa, to which clan Iwasaki belonged, proved a success from the outset, and grew with each vicissitude of the state. For when (1874) the Meiji government's first complications with a foreign country necessitated the des patch of a military expedition to Formosa, the administration had to purchase 63 foreign steamers for transport purposes, and these were subsequently transferred to the Mitsubishi company together with all the vessels (i7) hitherto in the possession of the Mail SS. Company, the Treasury further granting to the Mitsubishi a subsidy of £50,000 annually. Shortly afterwards it was decided to purchase a service maintained by the Pacific Mail SS. Company with 4 steamers between Yokohama and Shanghai, and money for the purpose having been lent by the state to the Mitsubishi, Japan's first line of steamers to a foreign country was firmly established, just 20 years after the law inter dicting the construction of ocean-going vessels had been rescinded.

A further purchase of foreign steamers was made in 1877 in connection with the suppression of the Satsuma rebellion, and these vessels, io in number, were handed over to the Mitsubishi, which, in 188o, found itself possessed of 32 ships aggregating 25,600 tons, whereas all the other vessels of foreign type in the country totalled only 27 with a tonnage of 6,5oo. In the follow ing year the formation of a new company was officially promoted. It had the name of the ky5do unyu kaisha (Union Transport Com pany) its capital was about a million sterling; it received a large subsidy from the state, and its chief purpose was to provide vessels for military uses and as commerce-carriers. Japan had now definitely embraced the policy of entrusting to private com panies rather than to the state the duty of acquiring a fleet of vessels capable of serving as transports or auxiliary cruisers in time of war. But there was now seen the curious spectacle of two companies (the Mitsubishi and the Union Transport) competing in the same waters and both subsidized by the treasury. After this had gone on for four years, the two companies were amalgamated (1885) into the Nippon yusen kaisha (Japan Mail SS. Company) with a capital of £i,ioo,000 and an annual subsidy of .i88,000, fixed on the basis of 8% of the capital. Another com pany had come into existence a few months earlier. Its fleet con sisted of 1 oo small steamers, totalling 1 o,000 tons, which had hitherto been competing in the Inland Sea.

Japan now possessed a substantial mercantile marine, the rate of whose development is indicated by the following figures :— Nevertheless, only 23% of the exports and imports was trans ported in Japanese bottoms in 1892, whereas foreign steamers took 77%. This discrepancy was one of the subjects discussed in the first session of the Diet, but a bill presented by the govern ment for encouraging navigation failed to obtain parliamentary consent, and in 1893 the Japan Mail SS. Company, without wait ing for state assistance, opened a regular service to Bombay mainly for the purpose of carrying raw cotton from India to supply the spinning industry which had now assumed great im portance in Japan. Thus the rising sun flag flew for the first time outside Far-Eastern waters. Almost immediately after the estab lishment of this line, Japan had to engage in war with China, which entailed the despatch of some two hundred thousand men to the neighbouring continent and their maintenance there for more than a year. All the country's available shipping resources did not suffice for this task. Additional vessels had to be purchased or chartered, and thus, by the beginning of 1896, the mercantile marine of Japan had grown to 899 steamers of 373,588 tons, while the sailing vessels had diminished to 644 of 44,00o tons. In the same year the Government, awake to the increasing menace of conflict with Russia on the mainland of Asia and determined in that event to be adequately supplied with transport facilities, passed, with the consent of the Diet, laws for the liberal en couragement of ship-building and navigation. The law for the encouragement of ship-building was abolished in 1920; that for navigation, after having been twice amended, still exists. Accord ing to this certain Japanese steamship companies are given mail subsidies for maintaining regular services to various parts of the world on a 5 year contract. Ships entitled to this subsidy must be of over 3,00o tons, with a speed of 12 knots or more, and not over 15 years old. The subsidy itself is at the rate of a maximum of 5o sen (is.) per 1,000 miles for a vessel of 12 knots speed and an additional io% for every knot in excess of that limit. The effect of the legislation alluded to above was marked. In the period of six years ended 1902, no less than 835 vessels of 455,000 tons were added to the mercantile marine, and the treasury found itself paying encouragement money which totalled six hundred thousand pounds annually. Ship-building underwent remarkable development. Thus, while in 1870 only 2 steamers aggregating 57 tons had been constructed in Japanese yards, 53 steamers totalling 5,38o tons and 193 sailing vessels of 17,873 tons were launched in 1900. By the year 1907 Japan had 216 private shipyards and 42 private docks, and while the government yards were able to build first-class line-of-battle ships of the largest size, the private docks were turning out steamers of 9,00o tons burden. When war broke out with Russia in 2904, Japan had 567,000 tons of steam shipping, but that stupendous struggle obliged her to materially augment even this great total. In operations connected with the war she lost 72,00o tons, but on the other hand, she built 27,000 tons at home and bought 177,000 abroad, so that the net increase to her mercantile fleet of steamers was 133,000 tons. At that time Japan was practically still in her infancy as a maritime carrying power; but she has since then made great strides, and in 2927 the gross total of her steamer tonnage was well over 3 million tons and that of her sailing-ship tonnage over a million tons. During the Great War her shipping was able, thanks to her remoteness from the scene of conflict and to the preoccupation of the Allied Powers, to reap a very rich harvest. The following table shows the growth of the mercantile marine during the last 20 years: These figures do not include steam-vessels which are not registered or sailing-ships of "koku" burden.

The principal shipping companies are the Nippon Yusen Kaisha (605,548 tons gross), the Osaka Shosen Kaisha tons gross), the Kukusui Kisen Kaisha (259,85o tons gross), the Toy6 Kisen Kaisha (58,367 tons gross), now run by the Nippon Yusen Kaisha, the Kawasaki Steamship Co. (211,166 tons gross), the Mitsui Bussan Kaisha (101,844 tons gross) and the Kinkai Yusen Kaisha (104,415 tons gross).

The total number of seamen in 1925 was of whom 3,496,066 were employed on steamships and 883,549 on sailing vessels. The number of Japanese qualified officers in the same year was 56,813. Originally quite a number of foreigners, mostly British subjects, were employed by Japanese steamship com panies either as navigating officers or engineers; but in 1925 there were only 132-all engineers.

In accordance with a resolution passed at the International Labour Congress of 1926 a Japan Shipping Union was established in the winter of that year to act as a seamen's employment agency and generally to attend to their interests. This took the place of the former Japan Seamen's Relief Society, and the expense of its maintenance is borne in suitable proportions by the Government, shipowners and seamen themselves.

Maritime Administration.-The

duty of overseeing all matters relating to the maritime carrying trade devolves on the Ministry of State for Communications, and is delegated by the latter to one of its bureaus (the Kwansen-kyoku, or ships super intendence bureau), which, again, is divided into three sections: one for inspecting vessels, one for examining mariners and one for the general control of all shipping in Japanese waters. For the better discharge of its duties this bureau parcels out the empire into 4 districts, having their headquarters at Tokyo, Osaka, Nagasaki and Hakodate ; and these f our districts are in turn subdivided into 18 sections, each having an office of marine affairs (kwaiji-kyoku).

Japan now stands third on the list of the principal maritime countries of the world.

Open Ports.-There

are 41 ports in Japan open as places of call for foreign ships. The principal of these (with the dates of their opening in brackets) are Yokohama (1859), Kobe (i868), Osaka (1899), Dairen (1906), Nagasaki (1859), Shimonoseki (1899), Moji (1899), Otaru (1899), Muroran (1899), Hakodate (1865), Yokkaichi (1899), Tsuruga (1899), Karatsu (1899), Kuchinotsu (1899), Keelung (1899), Tamsui (1899), Niigata (1867), Aomori (1906), Kushiro (1899), Takow (1899), and Anping (1899), Chemulpho (1883), and Fusan (1883).

Emigration.-Although

the Japanese are by nature an ad venturous race it can hardly be said that they make perfect material as colonists. There are wide spaces in their own North Island which have long been awaiting development ; but it appears singularly difficult to find settlers to migrate to them. Hopes too were expressed after the Russo-Japanese war that South Man churia would become an attractive field for the colonist. But this has not proved to be the case. Small traders have certainly flocked there in numbers ; but agriculturists practically not at all. There are various explanations for this phenomenon. In the first place while the Japanese thrives in countries in which the standard of living is higher than his own he cannot do so in countries in which it is lower. In Manchuria in consequence he is quite unable to compete with the hardy Northern Chinese. Again, to the vast majority of Japanese farming means the culti vation of rice,-a cereal for which neither Manchuria nor the Hokkaido is really suited. Moreover, the Japanese does not like extremes of temperature, for which reason neither the bitter cold of the Hokkaido and Manchuria in the north nor the moist heat of Formosa in the south is really to his taste. He flourishes best in temperature of moderately warm regions,-North America for instance. But in such places a disposition to exclude him frequently manifests itself, in the form of legislation or other wise. For this racial prejudice is partly responsible, the Japanese being for various reasons not easily assimilable; but economic causes are an equally important factor. Native labour looks at him with an unfriendly eye because it fears that his superior industry and his lower standard of living will work to its own prejudice. Whatever the causes, there is no question that the result is a blow to Japanese pride; but since one nation cannot force its society on another at the point of the sword, this anti Asiatic prejudice has to be respected.

The following figures show the number of Japanese living abroad in 1926: Liaotung leased territory . . ...... 93,354 China . . . . . ....... 147,263 Straits Settlements . . . . ..... 6,964 Philippine Islands . . . . . . . . . 9,807 Dutch East Indies . . . ...... 4,533 Europe . . . . . . . . . . . 3,36o United States . . . . . . . . . . 233,605 Canada . . . . . . . . . . . 19,885 Mexico . . . . . . . . . . . 4,018 Brazil . . . . . . . 55,481 Peru . . . . . . . . 11,786 Argentine ..... . . . . . . 2,731 Australia . . . . . . ..... 3,752 Sandwich Islands . . . . • • . • . 127,951 Other countries . . . ..... . 15,609 Total . . 640,099Foreign Residents.-The total number of foreigners residing in Japan in 1926 was 31,140, of whom 22,272 were Chinese. The chief other nationalities represented were British (including British Indians) . . . . . . 2,460 U.S. citizens ....... . . . • Germans ...... . . . . . . 1,139 French ........ . . . 461 There are also small numbers of Dutch, Swiss, Italians, Danes, Portuguese, Norwegians, etc.

Posts and Telegraphs.-The

government of the Restoration did not wait for the complete abolition of feudalism before organizing a new system of posts in accordance with modern needs. At first, letters only were carried, but before the close of 1871 the service was extended so as to incline newspapers, printed matter, books and commercial samples, while the area was extended so as to embrace all important towns between Hakodate in the northern island of Yezo and Nagasaki in the southern island of Kyushu. Two years later this field was closed to private enterprise, the state assuming sole charge of the business. A few years iater saw Japan possession of an ization comparable in every respect with the systems existing in Europe. In 1892 a foreign service was added. In 1871 the number of post-offices throughout the empire was only 579; but by 1927 it had increased to 8,784. In that year the number of letters dis tributed was over 3,906 millions, of parcels nearly 56,000,00o, and of telegrams delivered nearly 7o millions. The number of paid postal officials was 56,317. Japan labours under special difficulties for postal purposes, owing to the great number of islands included in the empire, the exceptionally mountainous nature of the country, and the wide areas covered by the cities in proportion to the number of their inhabitants. It is not sur prising to find, therefore, that the means of distribution are varied. The gross revenue from postal, telegraph and telephone services in 1926 was about 23 million pounds.

Postal Savings Banks.