Countries Where Irrigation Is Developed

COUNTRIES WHERE IRRIGATION IS DEVELOPED Egypt and the Sudan.—In describing the areas where irri gation has been developed in various countries it is only necessary to give a more detailed statement regarding one of them, and Egypt has been selected, as its very life depends on its irrigation, whereas in most other cases irrigation is subsidiary to rainfall. Ancient as irrigation is in Egypt, it was never practised on a really scientific system until after the British occupation. As everyone knows, the valley of the Nile outside the Tropics is practically rainless. Yet it was the produce of this valley that formed the chief granary of the Roman empire. Probably nowhere in the world is there so large a population per square mile depending solely on agriculture, and so free from the risk of a season of drought or of flood. This is due to a remarkable property of the Nile. The regimen of the river is nearly constant. The season of its rise and fall, and the height attained by its waters, vary from year to year to a comparatively small extent. Each year the river begins to rise in Egypt about the beginning of June, attains its maximum in September, diminishes at first rapidly, and then more slowly, until the following June brings a new cycle. A late rise is not usually more than about three weeks later than an early rise. From the lowest level in summer to the highest level in flood the rise is, on an average, about 3o ft. at Aswan. The highest flood may be about 5 f t. more, and this extra height may mean disaster to life in Lower Egypt if the Nile banks are not carefully maintained so that they may contain the flood be tween them, train it to the sea, and not allow of its spreading over the land, except as permitted for irrigation. The lowest flood since 1737 occurred in 1913 and rose only to about 8 ft. below the average. The next lowest Nile occurred in 1877, and caused widespread famine throughout Upper Egypt, as 947,000 ac. remained barren there because the water did not rise high enough to flow properly into the canals. The land revenue lost in that year, as it is chargeable only on areas watered, was £1,112,000. The thorough remodelling of the whole system of canals since 1883 abolished all danger of famine and disaster in other low years, and the loss of revenue in each of these years was com paratively slight. In 1907, for instance, when the flood was nearly as low as in 1877, the area left unwatered was little more than 0% of the area affected in 1877. The area of all Egypt is over 240,000,000 ac., of which about 5,200,000 ac. are cultivated; but about 7,200,00o ac. can be cultivated from the waters of the Nile. All the remainder, lying in plateau and hilly country high above the Nile, must continue in its present inhospitable state of bare rock and sand until a climatic change occurs.

Irrigation During Low Nile.

The khedive, Mehemet Ali, was advised to deepen the canals of Lower Egypt to draw water at even the lowest stage of the river, a gigantic and futile task for, as they were not laid out on scientific principles, the deep channels became filled with silt during the succeeding flood, and all the excavation had to be done over again year after year. Since they were never dug deep enough throughout to draw water from the very bottom of the river, the canals occasionally ran dry altogether in the month of June, when the river was at its lowest, and when, being the month of greatest need, water was most necessary for the cotton crop. Thus large tracts which had been sown, irrigated and nurtured for, perhaps, three months, perished in the fourth, while all the time the required precious Nile water was flowing uselessly to the sea. The obvious remedy was to throw a weir or barrage across each branch of the river to control the water, and so heighten the levels at which it flowed that it could pass into canals taken from upstream of the weirs. The task of designing such weirs was committed to Mougel Bey, a French engineer of ability, who constructed them at the apex of the Delta, about 12 m. north of Cairo, in 1861. The barrage consists of masonry platforms on which are built two stone bridges —one over the Damietta branch of the river having 71 spans, the other over the Rosetta branch, having C of 16.4 ft. each. The height of pier is 28.7 ft. from flooring to spring of arch, the latter being placed just above the surface level of a maximum flood. The movable gates placed between each of the piers were intended to increase the river level above the buildings by about 15 ft. The river supply could thus be made use of, and flow through a whole network of canals branching off the main canals taken off the river upstream of the barrage, and thus feed all Lower Egypt. For many reasons it would be unfair to blame Mougel because the work was condemned as being really a hope less failure, until it fell, in 1884, into the hands of British engi neers, with Sir Colin Scott Moncrieff at their head. The latter re solved that the barrage could be strengthened sufficiently to carry out its work. The strengthening works which enabled this to be 'done mainly concerned the masonry platforms, which were thor oughly grouted and extended. Further strengthening by means of subsidiary weirs erected immediately downstream of the various weirs was carried out, and the building as a whole made capable of carrying a designed head of water against it. Since 1901 a second weir has been constructed opposite Zifta, across the Damietta branch of the Nile, to improve the irrigation of the Dakhilia province.

The first alteration in Upper Egypt from the basin to the peren nial system of irrigation was due to the khedive Ismail, who acquired vast estates in the province of Assiut, Miniah, Beni Suef and the Fayoum, and resolved to grow sugar-cane on a large scale, and with this object constructed a canal, named the Ibra himia, taking out of the left bank of the Nile at the town of Assiut, and flowing parallel to the river for about 200 miles.

This canal had one defect ; it could not receive water in summer, as the river then was too low. It was decided, therefore, to con struct a barrage across the river for the same purpose as the Delta barrage, viz., to increase the level so that summer water could be made available as well as flood water. This structure was built at Assiut on a design very simi lar to that of the Delta barrage.

It consists of a wide masonry platform carrying a bridge of r arches each 5 metres' span, with piers of 2 metres' thickness. In each opening between piers are fitted two gates. The weir is about half-a-mile long. The work was begun at the end of 1898 and finished in 1902, and cost about £800,000.

The flood of 19o2 was extremely low and would have, if un aided, resulted in great loss of crop and revenue ; fortunately Mr. Webb (afterwards Sir Arthur Webb) grasped the significance of the power of control the new weir gave him over the height of the river upstream of the work, and used it for the novel pur pose of heading up the flood. It was the bold action of a compe tent engineer and was more than amply justified by the result. Further strengthening of the downstream toe of the floor became necessary, but was not costly. This system of heading up low floods has ever since been continued at Assiut, and its advan'ages have been the justification for the construction of the Esna bar rage in 1909, at the cost of about £900,000; this work renders the basin lands of the Kena province independent of a bad flood, but, like the Assiut barrage, it can be ultimately used to give summer water when such is available. Another similar structure with a similar object is now being erected at Nag Hamadi. With its completion Upper Egypt need never fear the effects of a low flood. It may be as well to say here that while a bad flood means low level in the river, yet no flood has ever been so low that there has not been enough water flowing to carry out all the irrigation required. What is really necessary is to make the water that is available flow at a high enough level, and it is this these barrages accomplish.

Storage.—These works, as well as those in Lower Egypt, are intended to raise the water surface above them and to control the distribution of supply, but in no way to store that supply. The necessity of storing up, for use at a future period of scarcity, of the superfluous flood discharge of the river, became apparent as a result of the development of Lower Egypt and the demand for perennial irrigation in Upper Egypt. The idea, however, was not a new one, and, if Herodotus is to be believed, it was a system actually pursued at a very early period of Egyptian history, when Lake Moeris, in the Fayoum, was filled at each Nile flood and drawn upon as the river ran down. When Sir Colin Scott Mon crieff first undertook the management of Egyptian irrigation many representations were made to him of the advantage of storing the Nile water; but he consistently maintained that before entering on that subject it was his duty to utilize every drop of the water at his disposal. This seemed all the more evident as at that time financial reasons made the construction of a costly Nile dam, to form a reservoir, out of the question. Every year, however, be tween 1890 and 19o2 the supply of the Nile during May and June was actually exhausted, no water at all being allowed then to flow out into the sea. In these years, too, owing to the extension of drainage works, the irrigable area of Egypt was greatly enlarged, so that if perennial cultivation was to be further increased it would be necessary to augment the volume of the river, and this could only be done by storing up some of the unused flood supply. The first difficulty that presented itself in carrying this out was that, during the months of high flood, the Nile is so charged with silt that to pond water up then would probably lead to the silt being deposited in the reservoir; this might in no great number of years render the reservoir useless. It was seen, however, that yearly, by the middle of November, the flood water was fairly free from deposit, while the volume of water was still so great that, without injuring irrigation, sufficient water might be stored to fill a great reservoir. Accordingly, when it was determined to construct a dam, it was decided that it should be supplied with sluices large enough to discharge, unchecked, the whole volume of the river until the middle of November, and then to begin storage.

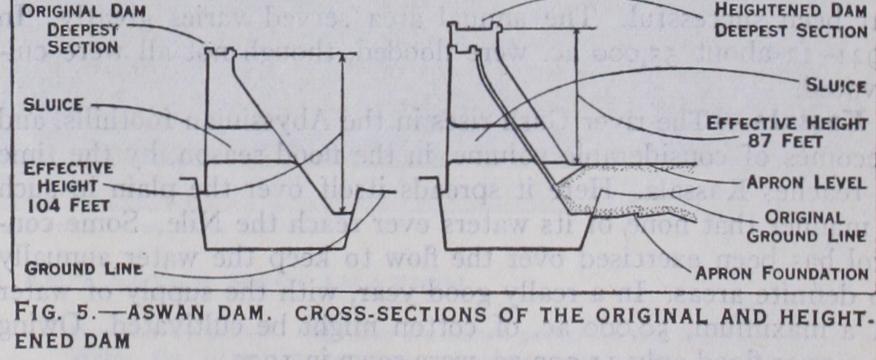

Sir Benjamin Baker, K.C.M.G., was entrusted with carrying out the work. He was one of the three eminent engineers, Mons. Boule (French) and Sig. Torricilli (Italian), being the others, who formed the commission to decide on the preliminary scheme prepared for the Government, but which was abandoned on Sir Benjamin Baker's advice. Then a new site was chosen. The new site for this great Nile dam was at the head of the first cataract above Aswan. A dike of syenitic granite here crosses the valley; so hard is it that the river had nowhere scoured a really deep chan nel through it, and on this the dam was erected, at a cost of about £3,000,000. The greatest head of water which could be put on the building was about 103 ft. It is pierced by 14o under sluices of 15o sq.f t. each, and by 40 upper sluices, each of 75 sq.f t. The reservoir could contain r,000 million tons of water. In the few years following 19o2 the need for an immediate further increase in the volume of water available for summer irrigation became pressing. As a consequence, it was decided to heighten the dam about 23 ft., thus increasing the reservoir capacity to 2,400, 000,00o tons of water. However, this was only done after the work of protecting the toe of the dam by aprons was completed. These aprons reduce the effective head of water against the dam so that, even when heightened 23 ft., the dam has not now so great an effective head against it as before, as may be seen from fig. 5.

The work of heightening was begun in 1907 and finished in 191 2, at a cost of about 1,5oo,000. The need of existing areas for all the water available was accentuated by the phenomenally low flood of 1913, which was followed, as a natural consequence, by a poor spring and summer supply in 1914. The 1913 flood was esti mated to be the lowest for 15o years, and except for the existence of the various barrages and the dam across the river, would have meant famine as well as financial disaster to the country.

The

Sudan.—Previous to 1910, except for a few thousand acres served by pumps, all the crops grown in the Sudan along the main Nile from Wadi Halfa to Khartoum, and along the White Nile from Khartoum to the Sudd region, were sown on land naturally inundated on its low banks by the annual rise of the Nile. On the Blue Nile, however, rainfall alone was depended on to fertilize the crops grown. About 1909 one of the few un cultivated areas below Khartoum was turned into a perennial irrigation farm, and was among the first to produce cotton in the Sudan by means of water pumped from the Nile. Soon after that date the possibility of growing cotton in the Gezira, that huge tract which lies in the fork of the Blue and White Niles, was sug gested by Lord Lovat. Here some 5,000,000 ac. form a gently slop ing plain stretching along between both rivers for about 200 m. from Khartoum. From this point southwards the plain is inter spersed with small, isolated granitic hills. Of the 5,000,000 ac.

in this plain, probably 3,000,00o ac. will form the maximum area cultivable. On the remaining 2,000,000 ac. near Khartoum the soil is said not to be so good ; it is of a more sandy nature.

Two experimental farms of a few hundred acres each were set down in the cultivable area. The summer climate in the Gezira was found to be too trying, although below Khartoum and in Egypt cotton is entirely a summer crop. An experiment was, however, made of sowing cotton in mid-July which could be picked in the following spring; this gave a return, on an average, of 400 lb. per acre, a figure equal to the normal Egyptian produc tion. This result was obtained at a season of the year when there is usually an abundance of water in the river, a most fortunate arrangement. In exceptional circumstances a final watering may be necessary as late as April 15, though normally the last watering is expected to be given by March 31. Before either of these dates Egypt, notwithstanding her great reservoir at Aswan, in years of low river requires all that the Blue Nile can supply. It became necessary, therefore, to devise a building which would act as a combined barrage and dam on the Blue Nile, to enable the ordi nary river supply to flow on to the plain; and at the same time store a sufficient volume of it to meet the demands in the Gezira in those months when Egypt requires all that flows in the river. It was decided to build such a structure at a point 5 m. south of Sennar, where a narrow belt of gabbro rock, which scarcely rises above the level of the plain on either side, runs across the river.

Construction was proceeded with and completed in July 1925 at a cost of about 16,000,000, the canal system bringing the total to about £9,000,000. The dam can store about 600 million tons of water for use in the critical period, which extends from January to March inclusive, when Egypt requires all that passes down in a very low year. The main canal leading from the dam is some 36 m. long before reaching the point where branch canals spread out from it on to the land to be irrigated. The area judged suffi cient to form a commercial proposition, in view of the cost of the works, and at the same time not to injure Egypt even in a phen omenally low year, was 300,00o ac. ; it is now known that this area can be considerably increased without endangering Egypt's supply.

Tokar.

Besides the Gezira plain the Sudan has other irriga tion areas where great improvements have taken place, as at Tokar and Kassala. The river Barakat rises in the rainy season in the Abyssinian hills, and rushes as a chocolate-coloured, thick stream on to the Tokar plain, where it eventually spreads out into a thin film which is sucked up by the thirsty soil. The plain, however, is much greater in extent than the water can cover, al though some finds its way to the sea, as recorded in 1921. The flood is liable to break away into areas not hitherto cultivated or, even if cultivated, so far from Tokar as to be inconvenient for transport. In recent years work was carried out for the purpose of exercising some control over the direction of flow, and has so far been successful. The annual area served varies greatly. In 1921-22 about 55,000 ac. were flooded, though not all were cul tivated.

Kassala.

The river Gash rises in the Abyssinian foothills, and becomes of considerable volume, in the flood season, by the time it reaches Kassala. Here it spreads itself over the plain in such a manner that none of its waters ever reach the Nile. Some con trol has been exercised over the flow to keep the water annually to definite areas. In a really good year, with the supply of water at a maximum, 50,000 ac. of cotton might be cultivated. Owing to a poor flood only ii,000 ac. were sown in 1925.

India.

Irrigation gives valuable aid in the fight against those periodic famines which always happen after monsoon rainfall fail ures in India, and it also causes an increase in production through its extension into new and suitable areas hitherto lying fallow. During 4o years, 1885-1925 in particular, developments have steadily progressed. Some 10,500,000 ac. were irrigated in 1878– ,9; 19,250,000 ac. at the beginning of the century and 28,000, 000 ac. in 1923-24. Additional works now under construction will add 2,500,000 acres. New schemes are contemplated which will add a further 4,750,000 acres. When completed they will bring the irrigated area of British India up to about 36,000,00o acres. These figures exclude the water supplied from the Punjab canals to 650, 000 ac. in the native States. The Sutlej valley project, mainly for the benefit of native States, will increase the total by a further 3,250,000 ac., making in the proximate future a grand total ofabout 40,000,00o ac. of irrigated land in all India.

In 1900-01 39,142 m. of channels were in operation; by 1920 21 this had increased to 55,202 m. or an average addition of about Soo m. of channels per annum. The annual revenue return is be tween 7% and 8% on the capital invested in Government irri gation works. The following table shows the acreage of crops ma tured during 1923-24 by means of Government irrigation systems compared with the total area under cultivation in the several provinces of India: Canada.—Irrigation in Canada has been, so far, very partially developed, and only in those provinces where extensive farming operations are in progress, such as Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba. Developments are based upon the Federal Irrigation Act of 1894, under which the ownership of all surface water supply is vested in the Crown, which grants the necessary licences for its use. Occasional droughts occur all over the wheat-growing belts; provision, however, is steadily and systematically being made to supply irrigation water, to counteract as much as possible their effects. On the eastern section of the Canadian Pacific Rail way company a census of the yields obtained and the water used by a group of ten farmers during 1924, shows that the average yield of wheat was 191 bu. per ac. with an irrigation of 4 in. deep plus rainfall; with two 4 in. irrigations the yields were from 3o to 35 bu. and with three 4 in. irrigations were as high as 43 bu. per acre. In this district the rainfall was 11.24 in.; of which 9.68 in. fell during the growing season.

Australia.

Owing to the lack of an adequate rainfall the advantages of irrigation appealed many years ago to Australians. At first the object aimed at was to develop in unoccupied ter ritory. While these efforts generally proved successful, in recent years the policy has been to extend irrigation to existing pastoral settlements; and some very large conservations of flood water schemes have been carried out, under which considerable areas of land are now in process of more intensive settlement.

The Murrumbidgee river (N.S.W.), is controlled by a dam 240 ft. high, at Burrinjack, which can conserve about 960,000,00o tons of water. The scheme is to irrigate about 200,000 ac., of which 120,000 ac. were settled by June 1923. They are mainly devoted to vegetable and fruit growing and dairying purposes.

In Victoria the principal irrigation works are on the Goulbourne, Murray, Loddon, Werribee and MacAllister rivers. While the works for some of these schemes were completed before 1910 the areas to be irrigated are still only in process of settlement, and extension of the works are from time to time taking place. In 1923, 350,727 ac. were irrigated.

The Dawson Valley scheme (Queensland), under construction in 1928, comprises a dam 140 ft. high, at Nathans Gorge, to impound about 3,100,000,000 tons of water. When completed it will be the second largest reservoir in the world. The area to be served is about 250,000 ac. ; the Inkerman irrigation area of 4,500 ac. is served by 23o shallow well pumps. Provision is being made to increase it to Io,000 acres. There are a number of smaller pump schemes at Townsville, Rockhampton, Gingera and Fairy mead, which collectively serve about 4,000 acres.

In South Australia the Rennearth scheme serves 7,85o ac., mainly fruit producing. The Murray river pumping plants serve 17,800 ac., and are being extended to serve a further I r,000 acres. The Cadett scheme serves about 1,200 ac., and is supplied with water pumped through 90 ft. of height. The Waikerie scheme serves about 9.80o ac. and has the water lifted through 150 ft. of head. The Kingston scheme serves 50o ac. ; the Moorook scheme serves i,000 ac. ; the Coodoyla scheme is ready to serve about 3,60o ac. ; which can be increased to 30,00o ac. of irrigable land. The Berni scheme serves 7,700 ac. ; the Chaffey scheme will serve 14,00o ac. ; the Murray swamp land scheme will eventually make available for irrigation 13,700 ac., of which 5,800 ac. are now culti vated. Smaller schemes serve about 10,000 ac. in all. In Western Australia the Harvey irrigation scheme serves 4,000 acres.

Union of South Africa.

Irrigation was at first confined to small schemes whose entire works usually lay within the boundary of one farm. Works of greater magnitude were made easier of accomplishment when the Cape Government, to encourage ;rriga tion, passed Acts in 1876-77. Completed irrigation schemes, although numerous, are individually small in area, none exceeding 10,000 acres. Among those under construction or development are some of considerable magnitude. These latter include the Great Fish river scheme, where 75,00o ac. are to be irrigated; the Sun days river scheme of 36,00o ac., and the Kamanassie river scheme of 28,00o acres.

The total area of land in South Africa under irrigation or in process of being brought under irrigation under Board schemes is about 350,000 acres.

China.

China, with its huge population of about 30o millions, has, no doubt, a very large area of irrigated land, but no statistics are available as to its extent except in a few small special districts where Europeans reside or have commercial interests. Hitherto engineering has been largely devoted to preventing the rivers in more than average floods overflowing their banks and inundating the land, an effect which has been many times accompanied by great loss of life. Commissioners have studied river control and the conservancy boards in recent years have reported on and carried out important works with this end in view. Quite obvi ously there is a large field in China for this form of development, and no doubt it will in time be followed by the more usual irri gation works.

`Iraq.

The construction of the Hindia barrage was one of the first steps undertaken in the modern regeneration of irrigation in this historical area. In 1925 the Diala Cotton company inaugu rated a great scheme whereby io8,000 ac. will be fertilized by water from the Diala river, a tributary of the Tigris. The com pany, it is understood, intends to extend its operations as fast as possible under its concession ; and a time can be envisaged when adequate control of the Euphrates and Tigris under conditions of peace and good government will allow of great areas of the arid plains of 'Iraq to be once again cultivated.

Italy.

The most highly developed irrigation in the world is probably that practised in the plains of Piedmont and Lombardy, where every variety of condition is to be found. The engineering works are of a high-class order, and from long generations of experience the farmer knows how best to use his water. The principal river of northern Italy is the Po, which rises to the west of Piedmont and is fed, not from glaciers like the Swiss torrents, but by rain and snow, so that the water has a somewhat high tern perature, a point of importance to the valuable meadow irrigation known as Marcite. This is only practised in winter, when there is abundance of water available, and much resembles the water meadow irrigation of England. The great Cavour canal is drawn from the left bank of the Po a few miles below Turin, and it is carried right across the drainage of the country. Its full flood dis charge is 3,80o cu.ft. per second, which happens between October and May. For summer irrigation Italy depends on the glaciers of the Alps and the great torrents of the Dora Baltea, and Sesia can be counted on for a volume exceeding 6,000 cu.ft. per second. Lombardy is quite as well off as Piedmont for the means of irri gation. The Naviglio Grande of Lombardy is a very fine work drawn from the left bank of the Ticino, and useful for navigation as well as irrigation. It discharges between 3,00o and 4,000 cu.ft. per second, and probably nowhere is irrigation carried on with less expense. Another canal, the Villoresi, drawn from the same bank as the Ticino, further upstream, is capable of carrying 6,700 cu.ft. per second. Like the Cavour canal the Villoresi is taken across the drainage of the country, entailing a number of very bold and costly works.

Spain and Portugal.

Irrigation has developed in a number of places in the peninsula since the beginning of the century and schemes for further works are being considered. None of those so far completed are of any great magnitude, but among the pro posals there is one for the irrigation of I 20,000 ac. of the Guadal quivir. The possibilities of this river are being studied for other areas, and are great if, by regulations of its excess flow in flood time, its water can be conserved for use in the drier periods of the year. On the Tagus a scheme near Villa Franca is now being sur veyed which, if carried out, will enable 30,00o ac. to be irrigated.

Greece.

Greece has recently entered into a contract to re claim and develop a great area of land in the Vardar valley in the region of Salonika and is at the present moment considering ten ders for similar works in the plain of Thessaly and the Struma and Drama valleys. These works will largely consist of draining the rivers which at present flow through the plains, so as to avoid the disastrous flooding which now constantly takes place, but it is also intended to utilize the waters running in the streams as much as possible for irrigation. With these works completed Greece will have somewhere in the region of 1,5oo,000 ac. added to her culti vated land, of which at least 5oo,000 ac. will be irrigated. It is said that in addition to the wonderful type of "Turkish" tobacco (the area where this is grown centres round Kavalla and is now Greek territory) cotton of the Egyptian type can also be grown on these plains.

Arabia.

An interesting irrigation development is the possi bility of reviving agriculture by its aid in the Yemen. A syndicate has been studying a project to examine the many reservoirs which in ancient times controlled flood waters for the benefit of agricul ture in that region. However, the prosecution of this scheme must await the settlement of political problems in that region.

Mexico.

In Mexico, and in particular in northern Mexico, where the rainfall is negligible in the lower or plain country, strips of land are cultivated near the rivers by irrigation. The total area is considerable, but there are no records of its extent. The works are individually limited in extent, but have been con structed entirely by private enterprise, and good results in crop are obtained from them.

South America.

An irrigation scheme on the Rio Negro was carried out in 1914 whereby 230,000 ac. are being developed. There are other minor irrigation works in the country. Many irri gation works have been carried out in the South and Central American republics but almost entirely by private enterprise.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-Sir C. C. Scott

Moncrieff, "Lectures on Irrigation in Egypt," Professional Papers of the Corps of Royal Engineers, vol. xix. (1893) ; Sir W. Garston, Report on the Basins of the Upper Nile, Egypt, No. 2 (1904) ; Sir M. MacDonald, Nile Control (Egyptian Government Press) ; Wilcocks and Craig, Egyptian Irrigation (2nd ed., 1899) ; Annual Reports, Irrigation Department, Local Govern ments of India ; Sir Hanbury Brown, Irrigation, its Principles and Irrigation as an aid to crop production is confined mainly to the arable lands of the Western States which receive an annual precipitation of 5 to 20 in. and a summer rainfall between April and Oct. I, of 1 to io in., although nearly i,000,000 ac. of rice is irrigated in Louisiana, Arkansas, Mississippi and Texas, where the annual rainfall is 4o to 5o inches. A relatively small quantity of water is used in drought periods in some of the Atlantic coast States in the production of truck and fruit crops. In 1919 the area irrigated in the United States, exclusive of the Atlantic coast States, was 19,191,716 ac., the States ranking first in the area 1847 and its progress has been recorded by each decennial census since 1889. In that year the area irrigated was 3,564,416 ac.; in 1909 it was ac.; and in 1919 it was as stated, 19, 191,716 acres. The latter figure represents the present status of development approximately, no large extensions having taken place since 1920, because of the general depression in agriculture.

irrigated being California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Utah and Wyoming, in the order named. The capital invested in irrigation enterprises was $697,657,328, or $36.35 an acre. The cost of preparing land for irrigation is estimated at or $18 an acre, and the gross annual value of the principal irrigated crops was $800,982,440 or $41.74 an acre. Relatively small areas were irrigated by the inhabitants of the south-western portion of the United States in prehistoric times. The customs and methods used were improved by the Spanish conquerors and their de scendants. Modern irrigation by the Anglo-Saxon race began in Seven agencies have been instrumental in accomplishing this development. The individual irrigator who either built a ditch himself or formed a partnership with one or more neighbours, and the co-operative companies, which are in reality larger groups of farmers acting together in building the necessary works, had to their credit 70% of the area reclaimed up to 192o. Public irriga tion corporations, known as irrigation districts, and commercial enterprises, have each reclaimed 91%; the United States bureau of reclamation 7%; private corporations operating under the Carey Act, 4%; and the U.S. Indian service, Competent authorities have estimated that there is in the Western States an area aggregating 44,000,000 ac. in addition to that already irri gated, which it is feasible to irrigate when agricultural and eco nomic conditions warrant. Thus the possibilities of irrigated agriculture in the Western States may be said to include a total area of 63,000,00o acres.

In outlining the salient features of irrigation in the United States other than by the statistics given above, it may be remarked that the principles of hydraulics and hydrology which govern to so large an extent the design of irrigation structures, are identical for all countries, and where differences are created they are caused mainly by differences in building materials, in the standards of engineering design and construction, or in the demands and re quirements of the water users. As has been indicated, the greater part of arid land reclamation has been brought about by farmers acting singly or in groups and organizations. These settlers were not financially able to build costly works and common practice involved the use of wood and temporary structures. In course of time, however, many land and water corporations were formed by the aid of foreign as well as domestic capital, for the purpose of exploiting the agricultural resources of the West. These were followed by legislative action by many of the States to enlarge the powers of farmers' organizations, principally by permitting them to bond their land holdings, so raising funds with which to build, purchase, and reconstruct irrigation systems. In 1902 Congress passed the Reclamation Act by which the Federal Government became an active participant in reclamation work. These three agencies, viz., the commercial enterprises, the irrigation districts and the nation, were financially able to employ experienced engi neers to design and construct permanent irrigation works. The work of building new systems, and remodelling and reconstructing existing enterprises, has been going on for 25 years and is still in progress, with the result that the makeshifts of earlier periods are being replaced gradually by substantial structures of concrete, plain or reinforced ; and a degree of efficiency and permanency is being attained in irrigation systems that will compare favourably with those of any other country. It is believed the United States ranks first in the number, dimensions and permanency of its con crete dams built to impound water for irrigation, in the efficiency of the mechanical equipment used to pump water for irrigation, and in the effectiveness of the appliances used to distribute water on farms.

The quantity of delivered water required for the irrigable lands of the Western States depends primarily upon such climatic in fluences as rainfall, temperature, sunshine, and evaporation, and to a less degree upon such factors as time and quantity of applica tion, soils and crops. Based on sectional averages, the seasonal net requirements of delivered water range from 1.25 acre-feet per acre, where the effective rainfall is 12 in. during the crop growing period, to as high as 3 acre-feet per acre where the annual precipitation is less than 1 o in., the crop-growing period long, and the temperature high.

The most notable achievements in irrigation in the United States in recent years consist in (I) the large number of pumping plants installed in Arizona and California for the dual purpose of lowering the ground water level, thereby effecting cheap drainage and providing water for irrigation; (2) the development and extended use of the border method of applying water (see Farmers' Bulletin No. 1,243 U.S. Department of Agriculture) ; and (3) the results of intensive and extensive studies of soil moisture in relation to crop production and drainage. (S. Fo.)