Isotopes

ISOTOPES is the term first applied by F. Soddy in 1913 to substances which, though they had different atomic weights, yet had identical chemical properties and occupied the same place in the periodic table of the elements. Over a century earlier Dalton had postulated that atoms of the same element are similar to one another and equal in weight. A little later Prout suggested that the atoms of all elements were composed of atoms of a primordial substance which he endeavoured to identify with hydrogen.

If both these theories were right, the atomic weights of all elements would be comparable with each other as whole num bers. This the chemists soon showed was quite incompatible with experimental evidence. It is true that many were very nearly whole numbers, far too many for the effect to be pure chance, but others, like chlorine, were hopelessly fractional. Of the two alter natives Dalton's is much the simpler from the chemical point of view and was therefore quite rightly chosen as a working hypoth esis. From this in course of time it developed into an article of scientific faith, and, despite the complete absence of positive evi dence in its support, no serious questions as to its validity were raised until late in the 19th century. Of such speculations those of Crookes were founded on unsound evidence and were soon dis credited. The question could not be settled by ordinary chemical methods, which employ countless myriads of atoms and could therefore only give a mean result, and it was only by the dis covery of radioactivity and the development of accurate methods of weighing individual atoms that the existence of isotopes was disclosed. The two advances were nearly contemporaneous but the first definite convincing proof of isotopy was found among the radioactive elements and their products.

The Radioactive Isotopes.

In 1906 Boltwood discovered ionium and found that it had similar chemical properties to thorium. Further research using the most delicate radioactive methods failed to indicate the slightest chemical separation of these two elements once they had been mixed, and even more surprising their spectra appeared to be identical. Other pairs of elements in the radioactive group showed corresponding identi ties and later investigations on the chemistry of the products of radioactive disintegrations enabled the chemical law of radio active change to be formulated (see RADIOACTIVITY). This stated that a radioactive element when it loses an alpha particle goes back two places in the periodic table; when it loses a beta particle it goes forward one place. An alpha particle is a helium nucleus of weight 4, whereas a beta particle is an electron of negligible weight. It follows that if a body loses one alpha and two beta particles it will be back again in the same place in the periodic table although it will have lost a mass equal to four units of atomic weight.

Isotopic Bodies Predicted.

Supported by this law, which he was the first to state in its most general form, Soddy boldly claimed that these "isotopic" bodies would be both chemically and spectroscopically indistinguishable. He also predicted that the lead produced by the disintegration of uranium would have an atomic weight 206, while that of the lead produced from thorium would be 208, and that consequently the atomic weight of the lead found in uranium minerals should be less than that of ordinary lead (207.2) while that of lead from thorium minerals should be greater. These predictions were amply vindicated by the work of experts on atomic weights (Richards, Honigschmid and others), and it was shown beyond all dispute that the isotopic leads, though they differed by the predicted amount in properties such as atomic weight, density, and solubility which depend di rectly on the weight of their atoms, in all others, which do not— atomic volume, boiling-point, melting-point, refractive index and spectrum—were quite indistinguishable.

Practical Utilization of Indicators.

The impossibility of separating isotopes has been utilized in ingenious manner by Hevesy and Paneth. By the addition of a small quantity of a radioactive isotope to an ordinary inactive element, the latter is, so to speak, indelibly labelled and can be followed by the methods of radioactivity, which are incomparably more delicate than those of chemistry. In this way the solubility of very insoluble salts can be readily determined. By the addition of a little thorium B, an isotope of lead, valuable information has been obtained on the assimilation of the salts of the latter element by living plants. The use of such radioactive indicators affords a direct proof of the ionic dissociation theory; it has led to the discovery of certain metallic hydrides and to the determination of the velocity of diffusion of molecules among themselves, an otherwise insoluble problem.

The reasoning which led to the discovery of isotopes among the products of radioactive disintegration could not, however, be applied to the vast majority of elements which are not radio active. For these there is only one direct method of testing Dal ton's postulate, namely, that of weighing their individual atoms. This can be done by the analysis of positive rays (see POSITIVE RAYS ) . The fact that when subjected to Sir J. J. Thomson's method of positive ray analysis certain elements gave definite sharp parabolas, and not mere blurs, constituted the first direct proof that atoms of the same element were, even approximately, of equal mass. For some time the results of the application of this method of analysis appeared to support the hypothcJis of Dalton, as the elements introduced into the discharge tube gave single, or apparently single, parabolas in the positions expected from their chemical atomic weights (see CONDUCTION OF ELEC TRICITY: Gases).

Examination of Neon.

But when, in 1912, neon was exam ined, the trace obtained was definitely double. The brighter curve corresponded roughly to an atomic weight of 20, the fainter companion to one of 22, the atomic weight of neon being 20.20. The line 22 could only be explained as due to a hitherto un known elementary constituent of neon. This agreed well with the new idea of isotopic elements which was just then emerging from the investigations on radioactivity, so that it was of importance to investigate the point as fully as possible. The first line of at tack was an attempt at separation by fractional distillation, hut the result was entirely negative. The second method employed was that of fractional diffusion through pipe-clay which gave a small, but definite, positive indication of separation. It there fore seemed probable that neon was a mixture of isotopes.

The Mass-Spectrograph.

By the time that research on the subject was resumed at the Cavendish laboratory in 1919, the ex istence of isotopes among the products of radioactivity had been proved beyond all reasonable doubt by the work on the atomic weight of lead. This fact automatically increased the value of the evidence of the complex nature of neon and the urgency of its definite confirmation. It was realized that separation could only be very partial at the best, and that the most satisfactory proof would be afforded by measurements of atomic weight by the methods of positive ray analysis. These would have to be so accurate as to prove beyond dispute that the accepted atomic weight lay between the real atomic weights of the two constitu ents, but corresponded with neither of them. The parabola method was not equal to this, but the required accuracy was achieved by means of the mass-spectrograph, an instrument cap able of analysing positive rays (q.v.) into a spectrum of focussed lines, a mass spectrum. The first mass-spectrograph built in 1919 compared masses with an accuracy of about I in I,000.

When neon was introduced into this apparatus, f our new lines made their appearance at 1o, I I, 20 and 22. The first pair are second order lines. All four are well placed for direct compari son with standard lines, and a series of consistent measurements showed that to within about one part in a thousand, the atomic weights of the isotopes composing neon are 20 and 22 respec tively. Ten per cent of the latter would bring the mean atomic weight to the accepted value 20.20, and the relative intensity of the lines agrees well with this proportion. The isotopic nature of neon was therefore settled beyond doubt. See Plate in Posi TIVE RAYS for the first order lines of neon and some of the refer ence lines with which they were compared.

Analysis of Chlorine.

The element chlorine was naturally the next to be analysed, and the explanation of its fractional atomic weight was obvious at once. Its mass-spectrum is characterized by four strong lines 35, 36, 37, 38. The simplest explanation of the group is to suppose that the lines 35 and 37 are due to the isotopic chlorines, and the lines 36 and 38 to their corresponding hydrochloric acids. The elementary na ture of 35 and 37 is indicated by their second order lines at 17.5 and 18.5, and also when phosgene was used, by the occur rence of lines at 63 and 65 due to COC1" and Later it was found possible to obtain the spectrum of the negatively charged atoms of chlorine. This showed only two lines 35 and 37, so that the lines 36 and 38 cannot be due to isotopes of the element. These results show that chlorine is a complex ele ment, and that its isotopes are of atomic weight 35 and 37. Spec tra II., III. and IV. show the results with chlorine taken with different field strengths.

Other Elements.

As the work progressed with other ele ments further interesting results were obtained. Some elements, such as carbon and oxygen, were found to be "simple"; that is, not mixtures of isotopes. This was to be expected from their whole-number atomic weights. The large majority proved "com plex," the number of isotopes tending to be greater in elements of high atomic weight. Tin has no less than I I isotopes.

Mass rays of the metallic elements, which are in the majority, cannot in general be produced in the ordinary vacuum discharge but they can be investigated by means of anode rays. Thus the constitution of the alkali metals was first discovered by the use of an anode consisting of a platinum strip coated with salts of the metals and heated electrically. Dempster, at Chicago, produced mass rays of metals by heating the element in a furnace and ionizing the vapour produced by electron impact. By this means he made the first analyses of magnesium calcium and zinc, and also confirmed the results already obtained for the lighter alkali metals.

More recently a large number of elements, including some of the rare earths, have been successfully attacked by means of the special method of "accelerated anode rays" (see PosITrvE RAYS) and in all 57 out of the 8o known non-radioactive ele ments have been analysed into their constituent isotopes or shown to be simple.

The Whole-Number Rule.

By far the most important gen eral result of these investigations is that, with the exception of hydrogen, the weights of the atoms of all the elements measured, and therefore almost certainly of all elements, are whole numbers to about one part in a thousand. Of course, the error expressed in fractions of a unit increases with the mass measured, but with the lighter elements the divergence from the whole-number rule is extremely small. This enables sweeping simplifications to be made in our ideas of mass.

The original hypothesis of Prout can now be restated with the modification that the primordial atoms are of two kinds: protons and electrons, the atoms of positive and negative elec tricity. According to the modern theory of the nucleus atom. (see ATOM ; MATTER) all the protons and about half of the elec trons are packed very close together to form a central, posi tively charged nucleus, round which the remaining electrons circulate, somewhat like the planets round the sun. All the spectroscopic and chemical properties of the atom depend on the net positive charge on the nucleus, which is the excess of protons over nuclear electrons. This is also clearly the number of plan etary electrons in the neutral atom ; it is called the "atomic num ber" and is actually the number of the element in the periodic classification: i for H, 2 for He, 3 for Li, and so on.

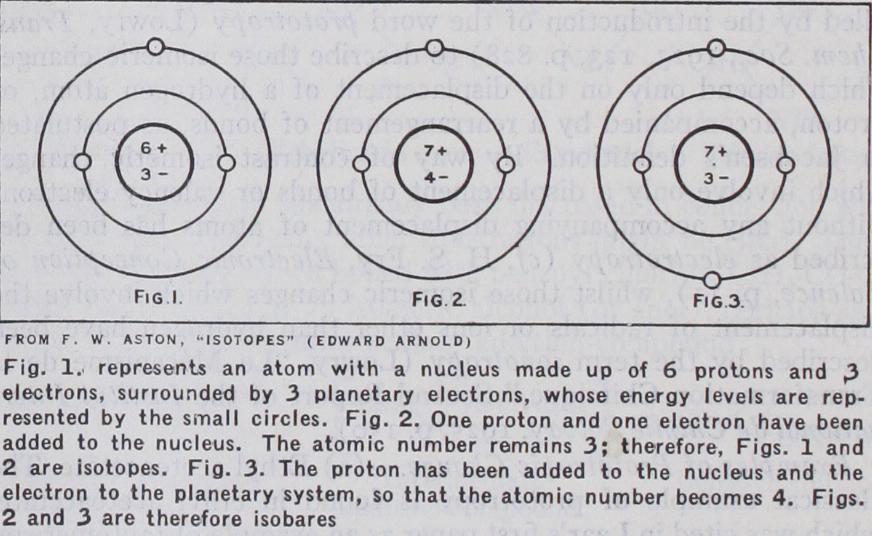

The whole-number weight of the atom, on the other hand, will be the total number of neutral pairs of protons and electrons it contains. This is also the number of protons in its nucleus, and is called the "mass-number" of the atom : i for H, 4 for He, 6 and 7 for the isotopes of Li, and so on. For the purpose of dis tinguishing isotopes it is customary at present to use the chem ical symbol of the complex element with an index corresponding to the mass-number of the particular isotope, e.g., Isotopes and Isobares.—Fig. i represents an atom with a nucleus made up of 6 protons and 3 electrons, surrounded by 3 planetary electrons. It must be borne in mind that the circles represent the energy levels of the latter, not their actual orbits. If we add i proton and r electron to the nucleus we shall get the atom represented in fig. 2. Here the atomic number remains 3 as before, the planetary electrons are unaffected and the chemical and spectroscopic properties unaltered but the weight of the atom will be increased by one unit. Figs. r and 2 are therefore atoms

of different weight but identical chemical properties, i.e., isotopes. They are in fact the isotopes of lithium Li' and Li'.

If on the other hand the proton is added to the nucleus and the electron introduced into the planetary system we obtain fig.

3. Here the weight is increased by r as before but the atomic number is now 4, the planetary system altered and the chemical properties changed. Figs. 2 and 3 therefore represent atoms hav ing the same weight but different properties; such substances are called isobares. Many pairs of isobares are known, the most strik ing being the most abundant constituents of argon and calcium having the same mass number 4o. It is difficult to imagine bodies more completely different in all outward properties yet no dif ference whatever has yet been detected between the weights of their atoms.

Packing Fraction.

If the additive law of mass were as true when an atomic nucleus is built of protons plus electrons as when a neutral atom is built of nucleus plus electrons, or a molecule of atoms plus atoms, the divergences from the whole number rule would be too small to be significant, and, since a neutral hydrogen atom is r proton plus I electron, the masses of all atoms would be whole numbers on the scale H= 1. The measurements made with the first mass-spectrograph were suffi ciently accurate to show that this was not true. The theoretical reason adduced for this failure of the additive law is that, inside the nucleus, the protons and electrons are packed so closely to gether that their electromagnetic fields interfere and a certain fraction of the combined mass is destroyed, whereas outside the nucleus the distances between the charges are too great for this to happen. The mass destroyed corresponds to energy released, analogous to the heat of formation of a chemical compound, the greater this is the more tightly are the component charges bound together and the more stable is the nucleus formed. It is for this reason that measurements of this loss of mass are of such fundamental importance, for by them we may learn something of the actual structure of the nucleus, the atomic number and the mass number being only concerned with the numbers of protons and electrons employed in its formation.

The most convenient and informative expression for the di vergences of an atom from the whole-number rule is the actual divergence divided by its mass number. This is the mean gain or loss of mass per proton when the nuclear packing is changed from that of oxygen to that of the atom in question. It is called the "packing fraction" of the atom and expressed in parts per 0,000. Put in another way, if we suppose the whole numbers and the masses of the atoms to be plotted on a uniform logarith mic scale such that every decimetre equals a change of r %, then the packing fractions are the distances, expressed in milli metres, between the masses and the whole numbers.

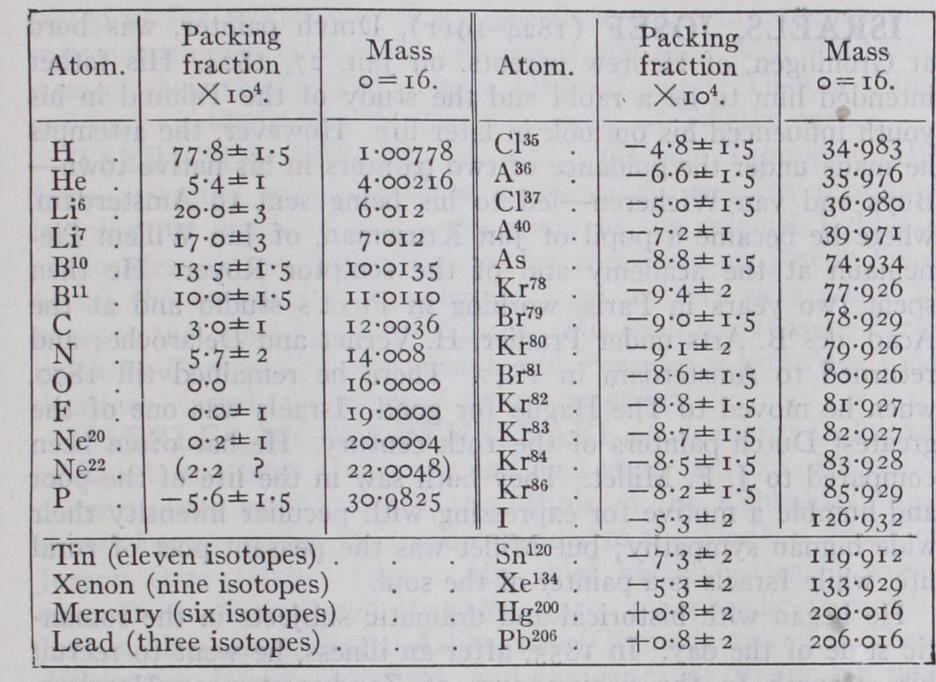

The original was not sufficiently accurate to detect the divergences from the whole-number rule except in the case of hydrogen. The atom of hydrogen weighs about 1.008 on the oxygen scale and its abnormal weight is clearly attributable to the fact that its nucleus consists of a single proton the mass of which will not be reduced by the packing effect described. In order to measure the packing fractions of other elements it has been necessary to build a special mass-spectrograph (see POSITIVE RAYS) with an accuracy of I in 10,000. The results obtained with this instrument are tabulated below. The table includes results for the lithium isotopes calculated from measurements made by Costa with an accuracy of I in 3,000.

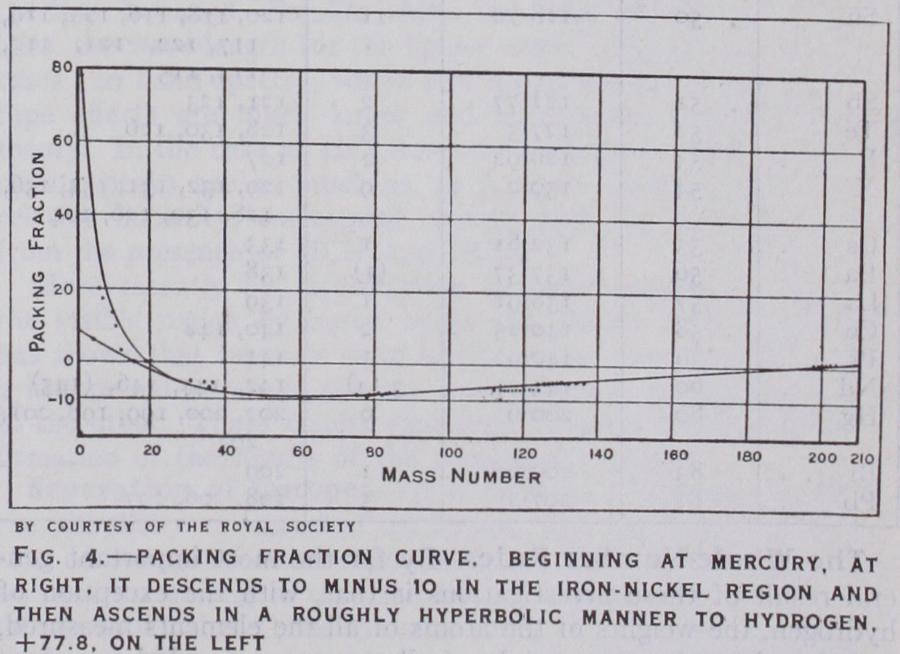

It will be seen that in addition to the first two fundanktntal constants of an atom, atomic number and mass number which settle the numbers of protons and electrons contained in its nu cleus, we now have a third, the packing fraction, which gives en tirely new information on the nucleus, for it is a measure of the forces binding those protons and electrons together. The discrim inating value of this information is clear at once, e.g., had the packing fraction of the helium atom not been greater than that of the oxygen atom it would have ruled out the possibility that the nucleus of the latter was simply built of f our unchanged helium nuclei or alpha particles, for there would have been no loss of energy, that is mass defect, in the latter to represent the binding forces holding the f our particles together. High packing fractions indicate looseness of packing, and therefore low nuclear stability; low packing fractions the reverse. When the packing fractions of the atoms are plotted against their mass-numbers, it is found that for all atoms above mass-number 20 these lie roughly on a single curve. (Fig. 4.) From mercury, whose packing fraction is hardly distinguish able from that of oxygen, the curve descends and reaches a mini mum of about io in the iron nickel region. It then ascends and in the case of atoms of odd atomic number continues to do so, in a roughly hyperbolic manner, right up to hydrogen +77.8. The light atoms of even atomic number have packing fractions well below this curve and approximate to a branch rising much less steeply to helium +5.4. This suggests that the light ele ments of odd atomic number have a common loosely packed, and theref ore heavy, outside structure, which is not present in the closer packed and more stable nuclei of helium, carbon and oxygen.

Isotopes and Atomic Weights.

The theoretical importance of chemical atomic weight has been somewhat reduced by the discovery that for so large a number of elements it merely repre sents a statistical mean. Its position as a natural numerical con stant associated with an element has now been taken by the atomic number, which indeed defines the element, though from the point of view of chemical analysis, the mean atomic weight is as important as ever. The anomalies shown by those elements which, by their atomic weights, appear out of their right order in the periodic table, are now open to the simplest explanation. Thus argon, in which the heavier of two isotopes predominates, has a greater mean weight than potassium, in which the reverse is the case. The same explanation applies to cobalt, nickel, tellu rium and iodine.

Since the atomic number only depends on the net positive charge on the nucleus, arithmetically any element can possess an indefinite number of isotopes. The table herewith shows that those present in detectable quantity are restricted both in num ber and range of weight, though the causes of these restrictions are at present unknown. No element of odd atomic number has more than two isotopes and, above atomic number 9, the mass numbers of the isotopes always differ by 2, and the lighter is the more abundant constituent. The number of nuclear electrons tends to be even. That is, in the great majority of cases even atomic number is associated with even mass-number, and odd with odd. Beryllium and nitrogen are the only elements consist ing entirely of atoms whose nuclei contain an odd number of electrons.

If the mass-numbers of the various species of atoms are plotted against their relative abundance in the earth's crust, a strong preponderance of those of type 8n may be seen. There is an extreme difference of range between the abundance of isotopes in an element and elements in nature. In the case of elements of an odd atomic number this cannot be ascribed merely to lack of delicacy in the means of detection of their isotopes. Thus while there are only about three Cl" atoms to one Cl" and about two atoms to one yet there are a thousand million more atoms of chlorine than of gallium. This suggests that isotopes have some relation in common more fundamental than that of identity of nuclear charge, an idea which is supported by other independent lines of reasoning.

Spectra of Isotopes.

As regards their series spectra, in which, on Bohr's theory, the two bodies concerned are an electron and an enormously more massive atomic nucleus, the prediction that isotopes should be indistinguishable is satisfied to a high degree of precision. So far the only effect detected is a minute difference of wave-length between the lines of Carnotite lead (206) and ordinary lead (207.2). The most accurate measurements by Merton indicate that this has a maximum value of o.on A for the line X=4058. Smaller shifts are detectable in a few other lines, the wave-length for the lighter atom being the greater in all cases. In band spectra, where two nuclei are concerned, the iso tope effects are much larger and in excellent agreement with theory. In the case of HC1 bands in the infrared region the du plicate peaks are as much as 14 A apart, and in position and relative intensity, correspond exactly with the results expected from the presence of HC1" and More recently by investigation of band spectra produced in the visible region by boron oxide and silicon nitride, Mulliken has shown that separate band heads appear corresponding to the 2 isotopes of boron, in the one case, and to 3 isotopes of silicon in the other. These results constitute valuable independent con firmation of the results of the mass-spectrograph.

Separation of Isotopes.

It is perhaps a fortunate thing for the simplicity of chemical arithmetic that the artificial separa tion of isotopes is excessively difficult, while at the same time no process tending to that end in nature appears to exist at all. Of the artificial methods the only one giving complete separation is the actual analysis of the mass-rays, during which the isotopic atoms strike the plate at different points and therefore, if col lected, would yield pure specimens. The quantities so produced would, with the means at present available, be far too minute to be of any practical value.

A

large number of methods for partial separation have been suggested and tried. The first successfully used, which is only applicable to gases, is that of free diffusion through pipe-clay or other suitable porous material. The diffusion rates are inversely proportional to the square roots of the masses concerned. It follows that if a large volume V of a mixture of isotopes is allowed to diffuse, leaving a small residue v, the latter will be richer in the heavier constituent than was the original gas. The actual numerical value of this enrichment, under ideal conditions, with isotopes, such as those of neon, which differ by io%, is only so that only by the use of very large volumes, or labo rious repetitions, can any measurable change be achieved. The original experiments with neon gave a shift of atomic weight of rather more than 0.1 of a unit. Harkins, at Chicago, by the use of 19,000 litres of HC1, was able to obtain considerable samples in which the atomic weight of chlorine differed by 0.055 unit.

Another method, following much the same numerical laws, is that of Bronsted and Hevesy, which consists of free evapora tion from a liquid surface at very low pressure. They obtained two samples of above 0.2 cc. of mercury differing in density by 5 parts in 10,000, or o.i of a unit. The atomic weights showed a corresponding difference, but the electrical conductivity of the two samples was indistinguishable to one part in a million.

Other methods of separation such as chemical action, centrifu ging, ionic migration and thermal diffusion have only yielded meagre or entirely negative results. A very large number of at tempts have been made in recent years to discover any variation in the chemical atomic weight of elements known to be complex, which would indicate a change in the proportions of the isotopes present. Boron, silicon, chlorine, iron and nickel have all re ceived attention, but in no case with any certain positive result. From their experiments on silicon from no less than 12 different terrestrial and meteoric sources, Jaeger and Dijkstra concluded that their products differed in density not more than 0.00004%.

The accumulation of negative evidence of this kind is very impressive, and supports the idea that the evolution of the ele ments, apart from those produced by radioactive disintegration, must have been such as to lead to a proportionality of isotopes which was constant from the start, and, since we know of no natural process of separation, has remained constant ever since.

See F. W. Aston, Isotopes (2nd ed., 1924) ; K. Fajans, Radioactivity (trans. from the 4th German ed. by T. S. Wheeler and W. G. King, 1923) ; E. N. da C. Andrade, The Structure of the Atom (1927).

(F. W. A.)