Italy

ITALY (Italia), the name applied both in ancient and in modern times to the great peninsula that projects from the mass of central Europe far to the south into the Mediterranean sea, where the island of Sicily may be considered as a continuation of the continental promontory. The portion of the Mediterranean commonly termed the Tyrrhenian sea forms its limit on the west and south, and the Adriatic on the east ; while to the north, where it joins the main continent of Europe, it is separated from the adjacent regions by the mighty barrier of the Alps, which sweeps round in a vast semicircle from the head of the Adriatic to the shores of Nice and Monaco.

The land thus circumscribed extends between the parallels of 40' and 36° 38' N., and between 6° 3d and 18° 3o' E. Its greatest length in a straight line along the mainland is from north-west to south-east, in which direction it measures 708 m. in a direct line from the frontier near Courmayeur to Cape Sta Maria di Leuca, south of Otranto, but the great mountain penin sula of Calabria extends about 2° farther S. to Cape Spartivento in lat. 37° 55'. Its breadth is, owing to its configuration, very irregular. The northern portion, measured from the Alps at the Monte Viso to the mouth of the Po, has a breadth of about 270 m., while the maximum breadth, from the Mont Cenis to Fiume, is far greater. The peninsula of Italy, which forms the largest portion of the country, nowhere exceeds 150 m. in breadth and does not generally measure more than Ioo m. across. Its southern extremity, Calabria, forms a complete peninsula, being united to the mass of Lucania or the Basilicata by an isthmus only 35 m. in width, while that between the gulfs of Sta Eufemia and Squillace, which connects the two portions of the region, does not exceed 20 miles. The area of the kingdom of Italy is 120,956 sq.m., or, excluding Sicily and Sardinia, 101,575. Though the Alps form throughout the northern boundary of Italy, the exact limits at the extremities of the Alpine chain are not clearly marked. Ancient geographers appear to have generally regarded the remarkable headland which descends from the Maritime Alps to the sea between Nice and Monaco as the limit of Italy in that direction, and in a purely geographical point of view it is probably the best point that could be selected. But Augustus, who was the first to give to Italy a definite political organization, carried the frontier to the river Varus or Var, a few miles west of Nice, and this river continued in modern times to be generally recog nized as the boundary between France and Italy. But in 186o the annexation of Nice and the adjoining territory to France brought the political frontier farther east, to a point between Mentone and Ventimiglia which constitutes no natural limit.

Towards the north-east, Augustus carried the frontier far enough to include Tergeste (Trieste), and the little river Formio (Risano) was in the first instance chosen as the limit, but this was subsequently transferred to the river Arsia (the Arsa), which flows into the Gulf of Quarnero, so as to include almost all Istria; and the circumstance that the coast of Istria was throughout the middle ages held by the republic of Venice tended to per petuate this arrangement, so that Istria was generally regarded as belonging to Italy, as it now does.

To the north the frontier is now fixed at the Brenner pass, at the head of the valley of the Adige. Here the main chain of the Alps (as marked by the watershed) recedes much farther to the north. In ancient times the upper valleys of the Adige and its tributaries were inhabited by Raetian tribes and included in the province of Raetia; and the line of demarcation between that province and Italy was purely arbitrary, as it was until after the war. Tridentum (Trento) was in the time of Pliny included in the tenth region of Italy or Venetia, but he tells us that the Tridentini were a Raetian tribe. Until 1919 the frontier between Austria and the kingdom of Italy crossed the Adige about 3o m. below Trento (q.v.).

While the Alps thus constitute the northern boundary of Italy, its configuration and internal geography are determined almost entirely by the great chain of the Apennines, which branches off from the Maritime alps between Nice and Genoa, and, after stretching in an unbroken line from the Gulf of Genoa to the Adriatic, turns more to the south, and is continued throughout central and southern Italy, of which it forms as it were the back bone, until it ends in the southernmost extremity of Calabria at Cape Spartivento. The great spur or promontory projecting towards the east to Brindisi and Otranto has no direct connection with the central chain.

One chief result of the manner in which the Apennines traverse Italy from the Mediterranean to the Adriatic is the marked division between northern Italy, including the region north of the Apennines and extending thence to the foot of the Alps, and the central and more southerly portions of the peninsula. No such line of separation exists farther south, and the terms central and southern Italy, though in general use among geographers do not correspond to any natural divisions.

Northern Italy.

By far the larger portion of northern Italy is occupied by the basin of the Po, which comprises the whole of the broad plain extending from the foot of the Apennines to that of the Alps, together with the valleys and slopes on both sides of it. From its source in Monte Viso to its outflow into the Adriatic—a distance of more than 280 m. in a direct line—the Po receives all the waters that flow from the Apennines north wards, and all those that descend from the Alps towards the south, Mincio (the outlet of the Lake of Garda) inclusive. The next river to the east is the Adige, which, after pursuing a parallel course with the Po for a considerable distance, enters the Adriatic by a separate mouth. Farther to the north and north-east the various rivers of Venetia fall directly into the Gulf of Venice.

The geography of northern Italy will be best described by following the course of the Po. That river has its origin as a mountain torrent descending from the north flank of Monte Viso, at more than 6,000 ft. above the sea; and after less than 20 M. it enters the plain at Saluzzo, between which and Turin (3o m.) it receives three considerable tributaries—the Chisone on its left bank, and the Varaita and Maira on the south. A few miles below Valenza it is joined by the Tanaro, which brings the waters of several minor rivers.

More important are the rivers that descend from the main chain of the Graian and Pennine alps and join the Po on its left bank. Of these the Dora (called for distinction's sake Dora Riparia), which unites with the greater river just below Turin, has its source in the Mont Genevre, and flows past Susa at the foot of the Mont Cenis. Next comes the Stura, which rises in the glaciers of the Roche Melon ; then the Orca, flowing through the Val di Locana; and then the Dora Baltea, which has its source in the glaciers of Mont Blanc, and thence descends through the Val d'Aosta for about 7o m. till it enters the plain at Ivrea, and, after 20m more joins the Po below Chivasso. (See SAINT BERNARD PASSES.) About 25 m. further on, the Po receives the Sesia, which rises at the southern foot of Monte Rosa, and falls into the Po 14 m. below Vercelli. A little above this confluence, at Casale Monferrato, the navigable portion of the river begins (337 m. to the mouth, minimum width 656 ft., minimum depth 7 ft. with many shallows and sandbanks. About 16 m. E. of Vercelli it is joined by the Ticino, a large and rapid river, which brings the outflow of Lago Maggiore (q.v.). The next great affluent, the Adda, flows out of the lake of Como at Lecco, and thence traverses the plain for 7o m. till it enters the Po between Piacenza and Cremona. It receives the waters of the Brembo, descending from the Val Brembana, and the Serio from the Val Seriana above Bergamo. The Oglio rises in the Monte Tonale above Edolo, and descends through the Val Camonica to Lovere, where it expands into the Lago d'Iseo (q.v.). From its south-west extremity, the Oglio has a long and winding course through the plain reaching the Po above Borgoforte. In this lower part it receives the smaller streams of the Mella, which flows by Brescia, and the Chiese, from the small Lago d'Idro, between the Lago d'Iseo and that of Garda.

The last great tributary of the Po is the Mincio, which flows from the Lago di Garda (q.v.) and has a course of about 4o m. from Peschiera, at its south-eastern angle, till it joins the Po. About 12 m. above the confluence it passes under the walls of Mantua (q.v.) and expands into a broad lake-like reach so as entirely to encircle that city.

The Adige, joined by the Isarco below Bolzano descends as far as Verona, where it enters the great plain, with a course from north to south nearly parallel to the rivers last described, but below Legnago it turns eastward and runs parallel to the Po for about 4o m., entering the Adriatic by an independent mouth about 8 m. from the northern outlet of the greater stream. The two rivers have, however, been joined by artificial cuts and canals, thus permitting free circulation between them.

The Po itself, which is here a very large stream, with an aver age width of 400 to 600 yd., parts into two arms, known as the Po della Maestra and Po di Goro, at S. Maria di Ariano, and these again are subdivided into several other branches, forming a delta above 20 M. in width from N. to S. The point of bifurcation, at present about 25 m. from the sea, was formerly much farther in land, more than 10 m. W. of Ferrara, where a small arm of the river, still called the Po di Ferrara, branches from the main stream. Previous to the year 1154 this channel was the main stream, and the two small branches into which it subdivides, called the Po di Volano and Po di Primaro, were in early times the two main outlets of the river. The southernmost of these, the Po di Primaro, enters the Adriatic about 12 M. N. of Ravenna, so that if these two arms be included, the delta of the Po extends about 36 m. from S. to N. The whole course of the river, including its windings, is estimated at 417 m.

In the first 21 M. of its course, down to Revello (west of Saluzzo), the Po descends no less than 5,25o ft., a fall of 47.3 :1,000. From the confluence of the Ticino its fall is about 0.3:1,000; from the beginning of the delta below Ferrara, 0.08:1,00o. At Turin it has an average width of 400 to 415 ft., a mean depth of 31 to 51- ft., and a velocity of I to 3 ft. in the second. The mean depth from the confluence of the Ticino (alti tude 217 ft.) downwards is 6 ft. to 15 ft. The total length of the embankments exceeds 600 miles. Owing to its confinement be tween these high banks, and to the great amount of sedimentary matter which the river brings down with it, its bed has been gradually raised, so that in its lower course it is often above the level of the surrounding country. A result is the rapid growth of the delta (13oo-1600, 127 ac.; 174 ac.). The Po della Maestra advances 282 ft. annually, the Po delle Tolle 262 ft., the Po della Gnocca I I I ft., and the Po di Goro 259 ft. The low ground between the lower Po and the lower Adige and the sea is known as Polesine.

Besides the delta of the Po and the large marshy tracts which it forms, there exist on both sides of it extensive lagoons of salt water, generally separated from the Adriatic by narrow strips of sand or embankments, partly natural and partly artificial, but having openings which admit the influx and efflux of the sea-water, and serve as ports for communication with the mainland. The best known and the most extensive of these lagoons is that in which Venice is situated, which extends from Torcello in the north to Chioggia and Brondolo in the south, a distance of above 40 m.; but they were formerly much more extensive, and afforded a continuous means of internal navigation by what were called "the Seven Seas" (Septem Mare), from Ravenna to Altinum, a few miles north of Torcello. That city, like Ravenna, originally stood in the midst of a lagoon; and the coast east of it to near Monfalcone, where it meets the mountains, is occupied by similar expanses of water, which are, however, becoming gradually con verted into dry land.

The tract adjoining this long line of lagoons is, like the basin of the Po, a broad expanse of perfectly level alluvial plain, extend ing from the Adige eastwards to the Carnic alps, where they approach close to the Adriatic between Aquileia and Trieste, and northwards to the foot of the great chain, which here sweeps round in a semicircle from the neighbourhood of Vicenza to that of Aquileia. The space thus included was known in ancient times as Venetia, a name applied in the middle ages to the well known city; the eastern portion of it became known in the middle ages as Frioul or Friuli, a district still interesting because of its peculiar form of Romance speech.

Returning to the south of the Po, the tributaries of that river on its right bank below the Tanaro which flow from the Ligurian Apennines, generally dwindle in summer into insignificant streams. The principal are : (I) the Scrivia, a small but rapid stream flowing from the Apennines at the back of Genoa; (2) the Trebbia, a much larger river which rises near Torriglia within 20 m. of Genoa, flows by Bobbio, and joins the Po a few miles above Piacenza; (3) the Nure, a few miles east of the preceding; (4) the Taro, a more considerable stream; (5) the Parma, flowing by the city of the same name; (6) the Enza ; (7) the Secchia, which flows by Modena; (8) the Panaro, a few miles to the east of that city; (9) the Reno, which flows by Bologna, but instead of holding its course till it discharges its waters into the Po, as it did in Roman times, is turned aside by an artificial channel into the Po di Primaro. The other small streams east of this have their outlet in like manner into the Po di Primaro, or by artificial mouths into the Adriatic between Ravenna and Rimini. The river Marecchia, which enters the sea immediately north of Rimini, may be considered as the natural limit of northern Italy. (See RuBicoN.) The Savio is the only other stream of any importance which has always flowed directly into the Adriatic from this side of the Tuscan Apennines.

The narrow strip of coast-land between the Maritime Alps, the Apennines, and the sea (called in ancient times Liguria [q.v.]), is throughout its extent, from Nice to Genoa on the one side, and from Genoa to Spezia on the other, almost wholly mountainous. The steep slopes facing the south enjoy so fine a climate as to render them very favourable for the growth of fruit trees, espe cially the olive, which is cultivated in terraces to a considerable height up the face of the mountains, while the openings of the valleys are generally occupied by towns or villages, some of which are favourite resorts.

From the proximity of the mountains to the sea the rivers in this part of Italy are generally mere mountain torrents. The largest descend from the Maritime Alps between Nice and Albenga. The Roja, which rises in the Col di Tenda and descends to Ventimiglia; the Taggia, between San Remo and Oneglia; and the Centa, which enters the sea at Albenga. The Lavagna, which enters the sea at Chiavari, is the only stream of any importance between Genoa and the Gulf of Spezia. But immediately east of that inlet (a remarkable instance of a deep land-locked gulf with no river flowing into it) the Magra, which descends from Pontre moli down the valley known as the Lunigiana, is a large stream, and brings with it the waters of the Vara. The Magra (Macra), in ancient times the boundary between Liguria and Etruria, may be considered as constituting on this side the limit of northern Italy.

The Apennines (q.v.), as has been already mentioned, here traverse the whole breadth of Italy, cutting off the peninsula properly so termed from the broader mass of northern Italy by a continuous barrier of considerable breadth, though of far inferior elevation to that of the Alps. The Ligurian Apennines are in fact only a continuation of the Maritime Alps. From the neigh bourhood of Savona to that of Genoa they do not rise to more than 3,000 to 4,000 ft., and are traversed by passes of less than 2,000 feet. As they extend towards the east they increase in eleva tion; the Monte Bue rises to 5,915 ft., while the Monte Cimone (7,103 ft.) is the highest point in the northern Apennine- , and thence between Tuscany and what are now known as the Emilian provinces a continuous ridge from the mountains at the head of the Val di Mugello (due north of Florence) runs to the point where they are traversed by the celebrated Furlo pass. The high est point in this part of the range is the Monte Falterona, above the sources of the Arno, which attains 5,410 feet. Throughout this tract the Apennines are generally covered with extensive forests of chestnut, oak and beech; while the upper slopes afford admirable pasturage.

2. Central Italy.—The geography of central Italy is almost wholly determined by the Apennines, which traverse it in a direc tion from about north-north-east to south-south-west, almost pre cisely parallel to that of the coast of the Adriatic from Rimini to Pescara. The line of the highest summits and of the watershed ranges is about 3o m. to 4o m. from the Adriatic, while about double that distance separates it from the Tyrrhenian sea on the west. In this part of the range almost all the highest points of the Apennines are found. Beginning from the group called the Alpi della Luna near the sources of the Tiber, which attain 4,435 ft., they are continued by the Monte Nerone (5,010 ft.), Monte Catria (5,590 ft.), and Monte Maggio to the Monte Pen nino near Nocera (5,169 ft.), and thence to the Monte della Si billa, at the source of the Nar or Nera, which attains 7,663 feet. Proceeding thence southwards, there are in succession the Monte Vettore (8,128 ft.), the Pizzo di Sevo (7,945), and the two great mountain masses of the Monte Como, commonly called the Gran Sasso d'Italia, the most lofty of all the Apennines, attaining to a height of 9,56o ft., and the Monte della Maiella, its highest sum mit measuring 9,170 feet. Farther south no very lofty summits are found till we come to the group of Monti del Matese, in Samnium (6,66o ft.), which according to the division here adopted belongs to southern Italy. Besides the lofty central masses enumerated there are two other lofty peaks, outliers from the main range, and separated from it by valleys of considerable extent. These are the Monte Terminillo, near Leonessa (7,278 ft.), and the Monte Velino near the Lake Fucino, rising to 8,192 ft., both of which are covered with snow from November to May.

But the Apennines of central Italy, instead of presenting, like the Alps and the northern Apennines, a definite central ridge, with transverse valleys leading down from it on both sides, in reality constitute a mountain mass of very considerable breadth, composed of a number of minor ranges and groups of mountains, which preserve a generally parallel direction, and are separated by upland valleys, some of them of considerable extent as well as considerable elevation above the sea. Such is the basin of Lake Fucino (q.v.) while the upper valley of the Aterno, in which Aquila is situated, is 2,38o ft. above the sea. The valley of the Gizio (see SULMONA) communicates with the upper valley of the Sangro by a plain called the Piano di Cinque Miglia, at an eleva tion of 4,298 feet. Nor do the highest summits form a continuous ridge of great altitude for any considerable distance ; they are rather a series of groups separated by tracts of very inferior elevation forming natural passes across the range, and broken in some places (as is the case in almost all limestone countries) by the waters from the upland valleys turning suddenly at right angles, and breaking through the mountain ranges which bound them. Thus the Gran Sasso and the Maiella are separated by the deep valley of the Aterno, while the Tronto breaks through the range between Monte Vettore and the Pizzo di Sevo. This con stitution of the great mass of the central Apennines has in all ages exercised an important influence upon the character of this portion of Italy, which may be considered as divided by nature into two great regions, a cold and barren upland country, bordered on both sides by rich and fertile tracts, and enjoying a warm but temperate climate.

The district west of the Apennines coincides in a general way with Etruria and Latium. The northern part of Tuscany is indeed occupied to a considerable extent by the underfalls and offshoots of the Apennines, which, besides the slopes and spurs of the main range that constitutes its northern frontier towards the plain of the Po, throw off several outlying ranges or groups. Of these the most remarkable is the group between the valleys of the Serchio and the Magra, commonly known as the mountains of Carrara. Two of the summits of this group, the Pizzo d'Uccello and the Pania della Croce, attain 6,155 feet and 6,100 feet. Another lateral range, the Prato Magno, which branches off from the central chain at the Monte Falterona, and separates the upper valley of the Arno from its second basin, rises to 5,188 feet.

The rest of this tract is for the most part a hilly, broken country, of moderate elevation, but Monte Amiata, near Radico fani, an isolated mass of volcanic origin, attains a height of 5,65o feet. South of this the country between the frontier of Tuscany and the Tiber is in great part of volcanic origin, forming hills with distinct crater basins, in several instances occupied by lakes (Lake of Bolsena, Lake of Vico and Lake of Bracciano). This volcanic tract extends across the Campagna of Rome, till it rises again in the lofty group of the Alban hills, the highest summit of which, the Monte Cavo, is 3,160 ft. above the sea. In this part the Apennines are separated from the sea, distant about 3o m., by the undulating volcanic plain of the Roman Campagna, from which the mountains rise in a wall-like barrier, of which the high est point, the Monte Gennaro, attains 4,165 feet. South of Palestrina again, the main mass of the Apennines throws off another lateral mass, known in ancient times as the Volscian mountains (now called the Monti Lepini), separated from the central ranges by the broad valley of the Sacco, a tributary of the Liris or Garigliano, and forming a large and rugged mountain mass, nearly 5,000 ft. in height, which descends to the sea at Terracina, and between that point and the mouth of the Liris throws out several rugged mountain headlands, which constitute the natural boundary between Latium and Campania, i.e., of cen tral Italy. Besides these offshoots of the Apennines there are in this part of central Italy several detached limestone mountains, rising like islands, of which the two most remarkable are the Monte Argentaro on the coast of Tuscany near Orbetello (2,087 ft.) and the Monte Circeo (1,77i ft.) at the extremity of the Pontine Marshes. The two valleys of the Arno (q.v.) and the Tiber (q.v.) form the key to the geography of central Italy west of the Apennines.

Towards the Adriatic the central range approaches much nearer to the sea, and hence, the rivers that flow from it are of little importance. From Rimini southwards they are: (I) the Foglia; (2) the Metaurus (q.v.); (3) the Esino; (4) the Potenza; (5) the Chienti; (6) the Aso; (7) the Tronto; (8) the Vomano; (9) the Aterno ; (io) the Sangro ; i) the Trigno, which forms the boundary of the southernmost province of the Abruzzi, and may therefore be taken as the limit of central Italy. This district is much broken up by these rivers and by smaller torrents, but is fertile, especially in fruit trees, olives and vines; and it has always been populous, with many small towns, but no great cities. Its chief disadvantage is the absence of ports, the coast preserving an almost unbroken straight line, with the single exception of Ancona, the only port worthy of the name on the eastern coast of central Italy.

3. Southern Italy.—The great central mass of the Apennines, which has traversed central Italy from north-west to south-east, continues in the same direction for about zoo m. farther, from the basin-shaped group of the Monti del Matese (which rises to 6,66o ft.) to the neighbourhood of Potenza, in the heart of the province of Basilicata, corresponding nearly to the ancient Lucania. The whole of the district known in ancient times as Samnium is occupied by an irregular mass of mountains, of much inferior height broken up into a number of groups, intersected by tortuous rivers. This mountainous tract, which has an average breadth of from 5o m. to 6o m., is bounded west by the plain of Campania, now called the Terra di Lavoro, and east by the much broader and more extensive tract of Apulia, composed partly of level plains, but for the most part of undulating downs, contrasting strongly with the mountain ranges of the Apennines, which rise abruptly above them. The central mass of the moun tains, however, throws out two outlying ranges, the one to the west, which separates the Bay of Naples from that of Salermo, and culminates in the Monte S. Angelo above Castellammare ft.), while the detached volcanic cone of Vesuvius (nearly 4,000 ft.) is isolated from the neighbouring mountains by an inter vening strip of plain. On the east side the Monte Gargano (3,465 ft.), a detached limestone mass projects in a bold spur-like promontory into the Adriatic, forming the only break in the otherwise uniform coast-line of Italy on that sea.

From the neighbourhood of Potenza, the main ridge of the Apennines runs nearly due south, within a short distance of the gulf of Policastro, and thence to the Monte Pollino, the last lofty summit. The range ,is, however, continued through the modern Calabria, to the southern extremity or "toe" of Italy, but the broken limestone range which is the true continuation of the chain as far as the neighbourhood of Nicastro and Catanzaro, and keeps close to the west coast, is flanked on the east by a great mass of granitic mountains, rising to about 6,000 ft., and covered with vast forests, from which it derives the name of La Sila. A similar mass, separated from the preceding by a low neck of Tertiary hills, fills up the whole of the peninsular extremity of Italy from Squillace to Reggio. (See ASPROMONTE.) The long spur-like promontory which projects towards the east to Brindisi and Otranto is merely a continuation of the low tract of Apulia, with a dry calcareous soil of Tertiary origin. The Monte Vulture, which rises in the neighbourhood of Melfi and Venosa to 4,357 ft., is of volcanic origin. Eastward from this the ranges of low bare hills called the Murgie of Gravina and Altamura gradually sink into those which constitute the peninsula between Brindisi and Taranto as far as the cape of Sta Maria di Leuca, the south-east extremity of Italy. This projecting tract, the "heel" of Italy, in conjunction with the great promontory of Calabria, forms the Gulf of Taranto, about 7o m. in width, and somewhat greater depth.

Of the rivers of southern Italy the Liris (q.v.) which has its source in the central Apennines above Sora, not far from Lake Fucino, and enters the gulf of Gaeta about io m. E. of the city of that name brings down a considerable body of water; as does also the Volturno, which rises in the mountains between Castel di Sangro and Agnone, flows past Isernia, Venafro and Capua, and enters the sea about 15 m. from the mouth of the Garigliano. About 16 m. above Capua it receives the Calore, which flows by Benevento. The Silarus or Sele enters the gulf of Salerno a few miles below the ruins of Paestum. Below this the watershed of the Apennines is near to the sea on the west. Hence the rivers that flow into the Adriatic and the gulf of Taranto have much longer courses, though all partake of the character of mountain torrents. Proceeding south from the Trigno, there are: (I) the Biferno and (2) the Fortore, both rising in the mountains of Samnium, and flowing into the Adriatic west of Monte Gargano; (3) the Cervaro, south of this great promontory; (4) the Ofanto, the Au fides of Horace, which rises about 15 m. W. of Conza, and in its lower course flows near Canosa and traverses the battlefield of Cannae (q.v.) ; and (5) the Bradano, which rises near Venosa, almost at the foot of Monte Vulture and flows towards the south east into the gulf of Taranto, as do the Basento, the Agri and the Sinni. The Crati, which flows from Cosenza northwards, and then turns abruptly eastward to enter the same gulf, is the only stream worthy of notice in Calabria ; while the arid limestone hills projecting eastwards to Capo di Leuca have no rivers at all. The only important lakes in Italy are those on or near the north frontier, already mentioned.

The lakes of central Italy, which are comparatively of trifling dimensions, belong to a wholly different class. The most important of these was the Lacus Fucinus (q.v.). Next in size is the Trasimene lake (q.v.). The neighbouring lake of Chiusi is of similar character, but much smaller dimensions. All the other lakes of central Italy, in the volcanic districts west of the Apen nines, occupy deep cup-shaped hollows, which have undoubtedly at one time formed the craters of extinct volcanoes. Such is the Lago di Bolsena, the smaller Lago di Vico (Ciminian lake), and the Lago di Bracciano, while to the south of Rome the lakes of Albano and Nemi have a similar origin.

The only lake in southern Italy is the small Lago del Matese in the heart of the mountain group of the same name. On the coast of the Adriatic north and south of the promontory of Gargano are brackish lagoons communicating with the sea.

For the three great islands of Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica, see the separate articles. Of the smaller islands that lie near the coasts of Italy, the most considerable is that of Elba (q.v.). North of this, and about midway between Corsica and Tuscany, is the small island of Capraia (q.v.). Gorgona (q.v.), about 25 m. far ther N., is still smaller. South of Elba are the equally insignificant islets of Pianosa (q.v.) and Montecristo (q.v.), while Giglio (q.v.) lies much nearer the mainland, immediately opposite the mountain promontory of Monte Argentaro. The islands farther south in the Tyrrhenian Sea are of an entirely different character. Of these Ischia and Procida, close to the northern headland of the bay of Naples, are of volcanic origin, as is the case also with the more distant group of the Ponza islands (q.v.). The island of Capri, on the other hand, opposite the southern promontory of the Bay of Naples, is a precipitous limestone rock. The Aeolian or Lipari islands (q.v.), a remarkable volcanic group, belong rather to Sicily than to Italy.

The Italian coast of the Adriatic presents a great contrast to its opposite shores, for while the coast of Dalmatia is bor dered by a succession of islands, great and small, the long and uniform coast-line of Italy from Otranto to Rimini presents not a single adjacent island ; and the small outlying group of the Tremiti islands (north of the Monte Gargano and about 15 m. from the mainland) alone breaks the monotony of this part of the Adriatic.

Geology.

The geology of Italy is mainly dependent upon that of the Apennines (q.v.). On each side of that great chain are found extensive Tertiary deposits, sometimes, as in Tuscany, the district of Monferrato, etc., forming a broken, hilly country, at others spreading into broad plains or undulating downs, such as the Tavoliere of Puglia, and the tract that forms the spur of Italy from Bari to Otranto.

Besides these, and leaving out of account the islands, the Italian peninsula presents four distinct volcanic districts. In three of them the volcanoes are entirely extinct, while the fourth is still in great activity.

The Euganean hills form a small group extending for about 10 m. from the neighbourhood of Padua to Este, and separated from the lower offshoots of the Alps by a portion of the wide plain of Padua. Monte Venda, their highest peak, is 1,890 ft. high.

2. The Roman district extends from the Alban hills (see ALBANUS Moms) to the Ciminian hills, and thence to the moun tains of Radicofani and Monte Amiata (q.v.). It is generally held that these volcanoes were at first submarine (which would account for the stratification found, and for the excellent quality of the volcanic tufa so much used for building stone) and that the coast was gradually raised. (See LATium.) 3. The volcanic region of the Terra di Lavoro is separated by the Volscian mountains from the Roman district. The highest cone of Roccamonfina, at the north-north-west end of the Cam panian plain called Montagna di Santa Croce, is 3,291 feet. The Phlegraean fields embrace all the country round l3aiae and Poz zuoli and the adjoining islands. Monte Barbaro (Gaurus), north east of the site of Cumae ; Monte San Nicola (Epomeus), 2,589 ft. in Ischia ; and Camaldoli, 1,488 ft., west of Naples, are the highest cones. The lakes Averno (Avernus), Lucrino (Lu crinus), Fusaro (Palus Acherusia), and Agnano are within this group, which has shown activity in historical times. A stream of lava issued in 1198 from the crater of the Solfatara, which still continues to exhale steam and noxious gases; the Lava dell' Arso came out of the north-east flank of Monte Epomeo in 1302; and Monte Nuovo, north-west of Pozzuoli (455 ft.), was thrown up in three days in Sept. 1538. Since its first historical eruption in 79, Vesuvius (q.v.) has been in constant activity.

4. The Apulian volcanic formation consists of the great mass of Monte Vulture.

The whole of the great plain of Lombardy is covered by Pleistocene and recent deposits. It is a great depression—the con tinuation of the Adriatic sea—filled up by deposits brought down by the rivers from the mountains. The depression was probably formed during the later stages of the growth of the Alps.

Climate and Vegetation.—The geographical position of Italy, extending from about 46° to 38° N., renders it one of the hottest countries in Europe. But the effect of its southern latitude is tempered by its peninsular character, bounded as it is on both sides by seas of considerable extent, as well as by the great range of the Alps with its snows and glaciers to the north. There are thus irregular variations of climate. Great differences also exist with regard to climate between northern and southern Italy, due in great part to other circumstances as well as to differences of latitude. Thus the great plain of northern Italy is chilled by the cold winds from the Alps, while the damp warm winds from the Mediterranean are to a great extent intercepted by the Ligurian Apennines. Hence this part of the country has a cold winter climate, so that while the mean summer temperature of Milan is higher than that of Sassari, and equal to that of Naples, and the extremes reached at Milan and Bologna are a good deal higher than those of Naples, the mean winter temperature of Turin is actually lower than that of Copenhagen. The lowest recorded winter temperature at Turin in 5° F. Throughout the region north of the Apennines no plant will thrive which cannot stand occasional severe frosts in winter, so that not only oranges and lemons but even the olive tree cannot be grown, except in spe cially favoured situations. But the strip of coast between the Apennines and the sea is not only extremely favourable to the growth of olives, but produces oranges and lemons in abundance, while even the aloe, the cactus, and the palm flourish in many places. The climatic frontier between Italy and Central Europe is thus formed rather by the Apennines than by the Alps.

Central Italy also presents striking differences of climate and temperature according to the greater or less proximity to the mountains. Thus the greater part of Tuscany, and the provinces thence to Rome, enjoy a mild winter climate, and are well adapted to the growth of olives as well as vines, but it is not till after passing Terracina, in proceeding along the western coast towards the south, that the vegetation of southern Italy develops in its full luxuriance. Even in the central parts of Tuscany, however, the climate is very much affected by the neigh bouring mountains, and the increasing elevation of the Apennines as they proceed south produces a corresponding effect upon the temperature. But it is when we reach the central range of the Apennines that we find the coldest districts of Italy. In all the upland valleys of the Abruzzi snow begins to fall early in Novem ber, and heavy storms occur often as late as May. The district from the south-east of Lake Fucino to the Piano di Cinque Miglia, enclosing the upper basin of the Sangro and the small lake of Scanno, is the coldest and most bleak part of Italy south of the Alps. Still farther south-east, Potenza has almost the coldest climate in Italy, and certainly the lowest summer temperatures. But nowhere are these contrasts so striking as in Calabria.

The shores, especially on the Tyrrhenian sea, present almost a continued grove of olive, orange, lemon, and citron trees, which attain a size unknown in the north of Italy. The sugar-cane flourishes, the cotton-plant ripens to perfection, date-trees are seen in the gardens, the rocks are clothed with the prickly-pear or Indian fig, the enclosures of the fields are formed by aloes and sometimes pomegranates, the liquorice-root grows wild, and the mastic, the myrtle, and many varieties of oleander, and cistus form the underwood of the natural forests of arbutus and ever green oak. But 5 or 6 m. from the shore, and often even less, the scene changes. High districts covered with oaks and chestnuts succeed to this almost tropical vegetation; a little higher up and we reach the elevated regions of the Pollino and the Sila, covered with firs and pines, and affording rich pastures even in the midst of summer, when heavy dews and light frosts succeed each other in July and August, and snow begins to appear at the end of Sep tember or early in October. Along the shores of the Adriatic, which are exposed to the north-east winds, blowing coldly from over the Albanian mountains, delicate plants do not thrive so well in general as under the same latitude along the shores of the Tyrrhenian sea.

Southern Italy indeed has in general a very different climate from the northern portion of the kingdom; and, though large tracts are still occupied by rugged mountains of sufficient eleva tion to retain the snow for a considerable part of the year, the dis tricts adjoining the sea enjoy a climate similar to that of Greece and the southern provinces of Spain. Unfortunately several of these fertile tracts suffer severely from malaria (q.v.), and espe cially the great plain adjoining the Gulf of Tarentum, which in the early ages of history was surrounded by a girdle of Greek cities (some of which attained to almost unexampled prosperity), has for centuries past been given up to almost complete desolation.

It is remarkable that, of the vegetable productions of Italy, many of which are at the present day among the first to attract the attention of the visitor are of comparatively late introduction, and were unknown in ancient times. The olive, indeed, in all ages clothed the hills of a large part of the country ; but the orange and lemon are a late importation from the East, while the cactus or Indian fig and the aloe, both of them so conspicuous on the shores of southern Italy, as well as of the Riviera Ponente, are of Mexican origin, and consequently could not have been intro duced earlier than the i6th century. The same remark applies to the maize or Indian corn. Many botanists are even of opinion that the sweet chestnut, which now constitutes so large a part of the forests that clothe the sides both of the Alps and the Apen nines, and in some districts supplies the chief food of the inhabit ants, is not originally of Italian growth; it is certain that it had not attained in ancient times to anything like the extension and im portance which it now possesses. The eucalyptus is of quite mod ern introduction; it has been extensively planted in malarious dis tricts. The characteristic cypress, ilex and stone-pine, however, are native trees, the last-named flourishing especially near the coast. The proportion of evergreens is large and has a marked effect on the landscape in winter.

Fauna.

The chamois, bouquetin and marmot are found only in the Alps, not at all in the Apennines. In the latter the bear was found in Roman times, and there are still a few remaining. Wolves are more numerous, though only in the mountainous dis tricts; the flocks are protected against them by large white sheep dogs, who have some wolf blood in them. Wild boars are also found in mountainous and forest districts. Foxes are common in the neighbourhood of Rome. The sea mammals include the common dolphin (Delphinus delphis). The birds are similar to those of central Europe ; vultures, eagles, buzzards, kites, falcons, and hawks are found in the mountains. Partridges, woodcock, snipe, etc., are among the game birds ; but all kinds of small birds are also shot for food, and their number is thus kept down, while many members of the migratory species are caught by traps in the foothills on the south side of the Alps, especially near the lake of Como, on their passage. Large numbers of quails are shot in the spring. Among reptiles the various kinds of lizard are notice able. There are several varieties of snakes, of which three spe cies (all vipers) are poisonous. Of sea-fish there are many varie ties, the tunny, the sardine, and the anchovy being commercially the most important. Some of the other edible fish, such as the palombo, are not found in northern waters. Small cuttlefish are in common use as an article of diet. Tortoiseshell, an important article of commerce, is derived from the Thalassochelys caretta, a sea turtle. Of fresh-water fish the trout of the mountain streams and the eels of the coast lagoons may be mentioned. The taran tula spider and the scorpion are found in the south of Italy.

The Vatican palace, the Lateran palace, and the papal villa at Castel Gandolfo, declared extraterritorial by the law of 1871, are now included in the new Papal State. The small republic of San Marino is the only other enclave in Italian territory. Italy is a constitutional monarchy, in which the executive power belongs exclusively to the sovereign, while the legislative power is shared by him with the parliament. He holds supreme command by land and sea, appoints ministers and officials, pro mulgates the laws, coins money, bestows honours, has the right of pardoning, and summons and dissolves the parliament. Trea ties with foreign powers, however, must have the consent of parliament. The sovereign is irresponsible, the ministers, the signature of one of whom is required to give validity to royal decrees, being responsible. Parliament consists of two chambers, the senate and the chamber of deputies, which are nominally on an equal footing, though practically the latter is more important. The senate consists of princes of the blood who have attained their majority, and of an unlimited number of senators above 40 years of age, who are qualified under any one of 21 specified categories—by having either held high office, or attained celeb rity in science, literature, etc. In 1928 there were 375 senators exclusive of ten members of the royal family. Nomination is by the king for life. Besides its legislative functions, the senate is the highest court of justice in the case of political offences or the impeachment of ministers.

Under the electoral law of 1928, the chamber is to consist of 400 deputies, and the whole kingdom is to form a single con stituency. The 13 National Confederations of industry (Confed erazioni nazionali dei sindacati) can propose 400 candidates be tween them (being eventually to be represented by a fixed number of deputies; but in the first instance they are to propose double the number of candidates by which they will ultimately be represented) and other associations, approved by a special committee of five senators and five deputies, can propose can didates up to the number of 200. The Grand Council of the Fascist Party will then form and publish in the Official Gazette the final list of candidates, not being restricted in its choice to those already proposed; and this list is to be voted on on the third Sunday after its publication as a whole, and by a simple "Yes" or "No." If the list is rejected (which may be regarded as extremely improbable) the court of appeal will order and fix the date of fresh elections. In these, lists of candidates may be submitted by all associations etc., which contain as many as 5,000 members who are qualified as electors; but these lists may not include more than three-quarters of the deputies to be elected. Each list is to be marked by an emblem, and, after ap proval by the court of appeal is to be voted on as a whole, that which obtains the majority of votes being carried as a whole i.e., on the scrutin de liste system. The remaining seats in the chamber are to be distributed among the remaining lists in pro portion to the votes they receive, i.e., on a system of proportional representation.

What, if any, is the role of the Fascist Grand Council under this contingency is, as has been pointed out, not altogether clear; and it is probable that the rejection of its list has hardly been seriously contemplated; for the Grand Council, though its posi tion was not regularized until 1928, has been the source from which all the acts of Fascism have emanated, and approval of the laws, which it has proposed by the chamber and the senate, has been a formality. It has now been enacted that it must be con sulted on all constitutional questions (such as questions regard ing the throne and the king, relations between Church and State, the nomination and prerogatives of the head of the Govern ment) ; that it is the supreme co-ordinating organ of the regime ; that ministers are ex officio members; and that it is to keep a list of possible ministers; that its decisions must be unanimous and its meetings secret; that it is to be summoned by the Duce, who settles all its agenda. Its members belong to three categories —members for an undetermined period, such as the Quadrumviri, the four leaders of the "march on Rome"; members of the Fascist hierarchy, during the period of their service, and members for three years (subject to prolongation) "who have deserved well of the nation and of the revolution." The right to vote is extended to all Italian citizens of 21 years of age and over, or to married men with children of 18 years of age and over. The elector must be either a contributor to a syndicate or confederation, or pay at least ioo lire a year in direct taxation, or be an employee of, or receive a pension from the State or a commune, or be a priest of the Roman Catholic or any other Church or denomination recog nized by the State. The number of electors for 1929 was 9,460,727. Senators and deputies receive salaries and have free passes on railways throughout Italy and on certain lines of steamers.

Parliaments are quinquennial, but the king may dissolve the chamber of deputies at any time, being bound, however, to con voke a new chamber within four months. The executive must call parliament together annually. Each of the chambers has the right of introducing new bills, as has also the Government but all money bills must originate in the chamber of deputies.

The consent of both chambers and the assent of the king is nec essary to their being passed. Ministers may attend the debates of either house but can only vote in that of which they are mem bers. The sittings of both houses are public and an absolute majority of the members must be present to make a sitting valid. The prime minister and head of the Government as his official title now runs holds the portfolios of the interior, foreign affairs, colonies, war, marine and air. The other ministries are finance, public instruction, communications, corporations (guilds), jus tice. Each minister is aided by an under-secretary of State.

There is a Council of State with advisory functions, which can also decide certain questions of administration, especially appli cations from local authorities and conflicts between ministries, and a court of Accounts, which has the right of examining all details of state expenditure.

The corporative or guild state is organized so as to give an efficient representation and an authoritative voice to associations of both employers and employed. Both are systematically or ganized in local, provincial and inter-provincial syndicates and unions leading up to national confederations of employers and workers representing all branches of production and all forms of activity. Those employed in State and Government service and in public charities are represented by special associations, com prising in 1928 62% of Italian manufacturers and 82% of all industrial workers, percentages which it is intended shall gradu ally rise until all are included. There are also intermediate na tional federations for each branch of industry, which are to study technical and administrative problems so as to improve output and reduce production costs; and there is a confederation of workers' syndicates, all under the general Fascist Confederation of industry, with a ministry of guilds (corporazioni) representing the authority of the State.

Provincial economic councils under the presidency of the pre fects have also been formed, which have to carry out the orders of the ministry of national economy and have taken the place of the old chambers of commerce. Their members are partly elec tive and partly Government functionaries resident in the locality. Agreements on wages and conditions of labour stipulated between these unions become binding on all employers and workers for the territories concerned, whether they have become members of the unions or not, and they must, if employers, contribute one day's wages per annum for each man in their employ, and, if workers, one day's pay, to these unions. Strikes and lock-outs are forbidden, and disputed points must be settled by the labour courts. The legal working day is eight hours, with a weekly day of rest and a yearly holiday. At the same time, in its labour charter the State declared in favour of private initiative—only when occasion demands will the State step in to safeguard na tional interest. The workers cannot be dismissed on the score of illness (unless prolonged) or military service, and are entitled to contributory insurance against accidents, sickness (including tuberculosis), unemployment and old age. The unions are to provide vocational training and organize employment bureaux, to which the employers must have recourse, giving preference to Fascists.

For the Opera Nazionale Dopolavoro see section on Education.

The provincial administration has similarly been brought com pletely under the control of the central Government. Each prov ince has a prefect as its head directly responsible to the min ister of the interior; he is the direct representative of the central executive, and is to act, not only against the enemies of the regime, but also against violence of any sort or kind, preserving order and exercising a strict control in matters of finance. The secretaries of the various federations and organizations depend ent on the Fascist party are to work in subordination to and in collaboration with the prefects. There are provincial "rectorates," taking the place of the previously existing provincial deputations and councils, each consisting of a presiding officer and "rectors," all of whom are to be appointed by royal decree. The sittings of these bodies are to be private.

Titles of Honour.

The former existence of so many sepa rate sovereignties and "fountains of honour" gave rise to a great many hereditary titles of nobility. Besides many hundreds of princes, dukes, marquesses, counts, barons and viscounts, there are a large number of persons of "patrician" rank, persons with a right to the designation nobile or signori, and certain hereditary knights or cavalieri. In the "Golden Book of the Capitol" (Libro d'Oro del Campidoglio) are inscribed 321 patrician families, and of these 28 have the title of prince and eight that of duke, while the others are marquesses, counts or simply patricians. For the Italian orders of knighthood see KNIGHTHOOD AND CHIVALRY : Orders of Knighthood. The king's uncle is duke of Aosta, his son is prince of Piedmont and his cousin is duke of Genoa.

Justice.

The judiciary system of Italy was mainly framed on the French model. Italy has courts of cassation at Rome, Naples, Palermo, Turin, Florence, 22 appeal court districts, 116 tribunal districts and 1,063 mandamenti, each with its own magistracy (pretura), 116 assize court districts and 327 detached sezioni di pretura. In 17 of the principal towns there are also pretori who have exclusively penal jurisdiction. For minor civil cases involving sums up to ioo lire, giudici conciliatori have also juris diction, while they may act as arbitrators up to any amount by request. The Roman court of cassation is the highest, and in both penal and civil matters has a right to decide questions of law and disputes between the lower judicial authorities, and is the only one which has jurisdiction in penal cases.

The pretori have penal jurisdiction concerning all misde meanours (contravvenzioni) or offences (delitti) punishable by imprisonment not exceeding three months or by fine not exceed ing 1,000 lire. The penal tribunals have jurisdiction in cases in volving imprisonment up to ten years, or a fine exceeding 1,000 lire while the assize courts, with a jury, deal with offences involv ing imprisonment for life or over ten years, and have exclusive jurisdiction (except that the senate is on occasion a high court of justice) over all political offences. Appeal may be made from the sentences of the pretori to the tribunals, and from the tri bunals to the courts of appeal ; from the assize courts there is no appeal except on a point of form, which appeal goes to the court of cassation at Rome. This court has the supreme power in all questions of legality of a sentence, jurisdiction or competency.

The penal code is now being unified and reformed. A special military tribunal for crimes against the state or the Fascist regime has recently been instituted. In civil matters there is appeal from the giudice conciliatore to the pretore (who has jurisdiction up to a sum of 1,50o lire), from the pretore to the civil tribunal, from the civil tribunal to the court of appeal, and from the court of appeal to the court of cassation.

The statistics of civil proceedings vary greatly from region to region. Whereas the general average for the whole country was 29.7 per 1,000 inhabitants in 1924, the figure for Tuscany (the lowest) was only 14.4, and no region of northern Italy exceeded 26.7 (Liguria). Farther south, on the other hand, the figures are much higher—Abruzzi 32.3 ; Sicily 35.3; Basilicata 41.1; Cam pania and Molise 42.9; Lazio 46.4; Apulia 53.2; Calabria 57.4; while Sardinia has the enormous figure of 95.9. For criminal proceedings, if we exclude mere offences against regulations, or contravvenzioni (see below) with a general average of 16.71 per 1,000 for 1924, the variation is similar, the Marches and Umbria coming lowest with 9.89 per 1,000 inhabitant, while Liguria (18.59) and Venezia Giulia (19.57) are the highest for northern Italy. For the south the figures are : 15.23 for Sicily; 20.99 for Lazio; 22.18 for Apulia ; 25.19 for Campania and Molise; 25.86 for Basilicata ; 26.46 for the Abruzzi; 31.72 for Sardinia and 32.85 for Calabria, in most cases showing a considerable diminu tion on those for 1923.

A royal decree of 1891 established three classes of prisons : judiciary prisons, for persons awaiting examination or persons sentenced to arrest, detention or seclusion for less than six months; penitentiaries of various kinds (ergastoli, case di reclu sione, detenzione or custodia), for criminals condemned to long terms of imprisonment ; and reformatories, for criminals under age and vagabonds. Capital punishment was abolished in 1877, penal servitude for life being substituted. This generally in volves solitary confinement of the most rigorous nature, and, as little is done to occupy the mind, the criminal not infrequently becomes insane. Capital punishment has, however, been rein troduced for crimes against the State. Certain types of dangerous individuals and political prisoners are relegated after serving a sentence in the ordinary convict prisons, and by administrative, not by judicial process, to special penal colonies known as dornicilii coatti or "forced residences." The establishments are, however, unsatisfactory, being mostly situated on small islands, where it is often difficult to find work for the coatti, who are free by day, being only confined at night. They receive a small and hardly sufficient, allowance for food of 10 lire a day, which they are at liberty to supplement by work if they can find it or care to do it. "Confino politico" or forced residence under sur veillance, may also be inflicted : but as to this no figures are available.

Notwithstanding the construction of new prisons and the trans formation of old ones, the number of cells for solitary confine ment is still insufficient for a complete application of the penal system established by the code of 1890, and the moral effect of the association of the prisoners is not good, though the sys tem of solitary confinement as practised in Italy is little better. The total number of prisoners, including minors and inhabitants of enforced residences, was 76,066 (2.84 per 1,000 inhabitants) in 1871 and on Dec. 31, 1903 was 65,819 (including 6,044 women, or less than i o%). Of these 31,219 were in lockups, 25,145 in penal establishments, 1,837 minors in Government and 4,547 in private reformatories, and 3,071 (males) were coatti, or inmates of forced residences (all on small islands). In 1928 there were 30,423 men and 3,566 women in prisons, of whom about two thirds were awaiting trial; 11,317 men and 293 women in penal establishments; 1,932 males in Government and 564 in private reformatories (the females, 941 in number, being sent only to the latter) ; and 564 coatti were inmates of forced residences.

Crime.—Statistics of offences, including contravvenzioni or breaches of by-laws and regulations, exhibit a considerable in crease per ioo,000 inhabitants since 1887, and even some increase on the figures of 1897. The figure was 1,783.45 per 100,000 in 1887; 2,164.46 in 1892; 2,546.49 in 1897; in 1902; and 3,159 in 1924 (1,671 crimes and 1,488 contravven zioni). The increase is partly covered by contravvenzioni, but almost every class of penal offence shows a rise including homicide, and that has risen considerably since 1902 : 5,418 in 1880; 3,966 in 1887; 4,408 in 1892; 4,005 in 1897; in 1902; and 4,259 in 1924 (of the last many must have been due to political disputes) ; and Italy remains, owing to the use of the knife, the European country is which homicide is most frequent.

Procedure, both civil and criminal, is somewhat slow, and the preliminary proceedings before the juge d'instruction occupy much time ; and in murder trials, by the large number of wit nesses called (including experts) and the lengthy speeches of counsel, have sometimes been dragged out to an unconscionable length ; but much has been done recently to "speed up" the procedure. In 1902, of 884,612 persons accused of penal offences, 13.12% were acquitted during the period of the instruction; 30.31 by the courts; 46.32 condemned; and the rest acquitted in some other way. This shows that charges, often involving pre liminary imprisonment, had been brought against an excessive pro portion of persons who either were not or could not be proved to be guilty; but in 1925 the figures were very different. Of 984,095 persons accused, 15.4% were acquitted during the instruction; 22.6% by the courts; and the remaining 62% were condemned.

As in most civilized countries, the number of suicides in Italy has increased from year to year and the rate which was 63.6 per 1,000,000 in 1901, has gone up to 92 per i,000,000. Trieste has the highest rate (446 per 1,000,000) of any city of Italy.

National Growth.—A remarkable general increase of the Italian population took place between 1910 and 1931. The losses due to the war, to epidemics and disasters and to the decrease of births in the years 1916-19, failed to check the increase, since they were balanced by the return of a number of emigrants (esti mated at about i,000,000) while comparatively few, about 363,000 have since left the country. Thus, it is estimated that the 34,600, 00o enumerated in the 1911 census, giving a density of 121 to the sq.km. had increased by April 21, 1931 to 41,176,671, or 133 to the sq.km. (including the restored territories, which are more sparsely populated than the peninsula), and this in a country two-thirds mountainous or very hilly, poor in minerals and with a soil exploited by some 3,00o years of cultivation.

The birth-rate, like that of most countries, shows a continuous decline since the '7os, but infant mortality has also diminished. The increase in the number of marriages has compensated for the decrease during the war, but the birth-rate per marriage is only at the pre-war level.

This rapid increase has resulted in the flooding of the labour market. The number of workers between the ages of 16 and 25 is probably about 24,000,00o as against about 20,500,00o in 1911. The difficulty of absorbing this mass of labour would have been even greater than it has been were it not for improvements in industrial equipment, factory organization, agricultural technique and also the extension of Italian territory. The pressure, how ever, is increased by the great number of war victims, who are unable to contribute their full share of work. Notwithstanding the difficulty of finding an outlet for Italy's surplus population by emigration and the existence of a certain amount of unem ployment (the official figures for the end of July 1928, were 021), the present regime is desirous of effecting a large increase in it, being firmly persuaded that man power counts high in the greatness of a nation. Various measures have been taken to this end, such as the formation of a national maternity and infancy board, the imposition of a tax on bachelors (35 lire between 25 and 35, 5o lire between 35 and 5o, 25 lire between 5o and 65 per annum, which is susceptible of increase), from which priests, seriously wounded soldiers, officers (whose marriage is subject to conditions) and all foreigners are exempt, and a large measure of exemption from taxation for the heads of families with seven or more children. Any attempt at spreading Malthusian tenets is to be sternly dealt with, and general and family morality are being upheld in various ways.

The new reclamation scheme, to which 3,800,000,000 lire has been allotted, to be spread over 3o years (an equal sum being spent by the landowners), while the scheme itself is to be com pleted in 14 years, will provide more land for cultivation: and a migratory scheme whereby families are removed from over populated districts to places where labour is required, will also help in this regard. 5,962,508 ac. are to be reclaimed as follows: 3,301,665 in Northern, 590,058 in Central, and 1,635,648 in Southern Italy, in Sicily and 317,202 in Sardinia. Five million acres more have been declared to be fit for more intensive cultivation and if the landowners do not undertake this in accord ance with the plans of the Government experts, so that the transformation of agriculture may be carried out with the least possible delay, the prefect of the province may step in and take the work over; or if no improvements are carried Gut at all, the State will (as has already been done near Rome) simply take possession of the land—on the principle that the State takes precedence of the individual, and that on his good conduct de pends the continuance of private ownership. Compensation is to be fixed by the State, and the Savings Banks of Lombardy and Turin, two of the most important, have been placed under Fascist presidents, who are not likely to cause any delay in granting the necessary funds. It has been calculated that some 200,000 men will be eventually employed in carrying out the scheme, and that food for some io,000,000 more Italians will eventually be grown at home. For comparison it may be stated that from the union of Italy to March 1928, 2,720,647,059 lire had been spent on land reclamation, of which 1,086,189,757 lire had been provided by the present Government (since October 1922), though, owing to the fall in the value of the lire, this is in reality only about one-tenth of the whole. A new Ente Nazionale pu la Cooperazione, instituted in 1926, is charged with the reorganization of the co-operative system, which has been most successful in the case of the War Veterans Association (Opera Nazionale dei Combattenti) in the sphere of land reclama tion and land settlement.

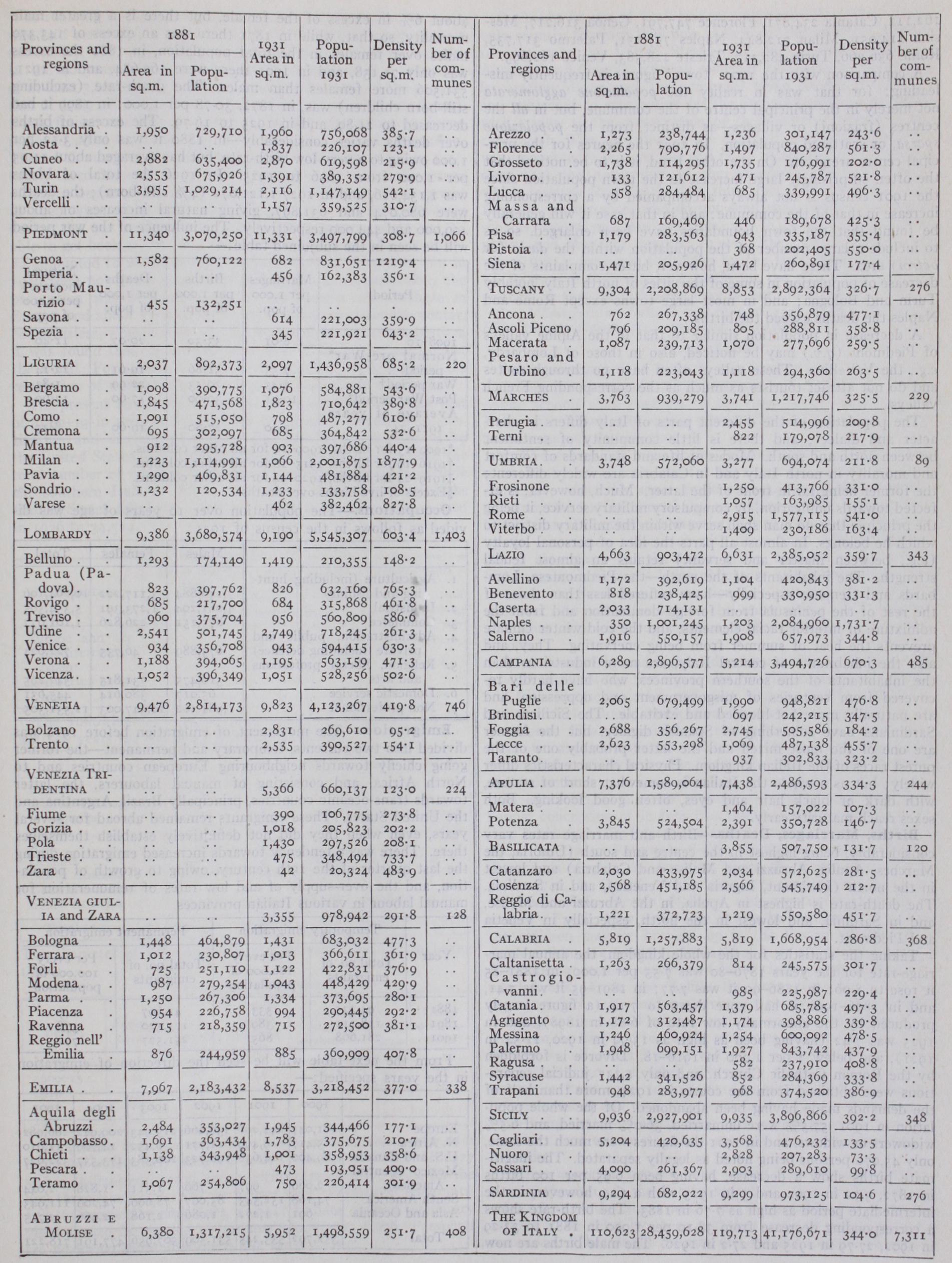

Census Figures.—The table on p. 761 gives the area and popu lation of each province and region in Italy in 1881. By 1927, as a result of the war of 1914-18, new provinces had been acquired and many of the old provinces had been reorganized, and so the table also shows the area of the acquired provinces and of the new divisions of the old provinces. In addition, the distribution of the 1921 population in these new administrative divisions, along with the density of the poptIlation per square mile, and the number of communes in each province, is indicated.

The actual population (not the resident or the "legal") of Italy since 177o is approximately given in the following table (the first census of the kingdom as a whole was taken in 1871) :— It is estimated that the total population resident in Italy in 1935 was 42,621,00o.

The average density increased from 257.21 per sq.m. in 1881 to 293.28 in 1901 and 344 in 1931. In Venetia, Emilia, the Marches, Umbria and Tuscany, the proportion of "concentrated" population (i.e., population resident in the town or village which forms the centre of each commune) was only from 45 to 59% in 1921 : in Calabria, the Abruzzi, Piedmont, Liguria, Lombardy, Venezia Tridentina, the proportion rose from 72 to 82%; in Venezia-Giulia, Lazio, Campania, Basilicata, Apulia, Sicily and Sardinia, it ran from 84 to 93%, being highest of all in the last named.

The following towns had a population of over 100,000 in 1931 (city only, not commune) Bari Belle Puglie 148,292, Bologna, 162,111, Catania 234,871, Florence 747,791, Genoa 316,217, Mes sina 114,051, Milan 712,844, Naples 757,251, Palermo Rome 656,266, Turin 482,117, Trieste 228,583, Venice A comparison with the 1901 "town" figures is frequently mis leading: for that was in reality the popolazione agglomerate not merely in the principal centre of the commune, but in all the centres (frazioni) or villages—as distinct from the popolazione sparsa, or scattered population. In 1921 the figures for the prin cipal centre are given. On the other hand, it is to be noticed that the often surprisingly large increase in the town population since the 1901 census is not always accompanied by a corresponding increase in that of the commune : and in that case it will generally be found that the town boundaries have been enlarged, so as to include a large number of the population within the dazio (or octroi) area. There have been, however, bitter complaints of the decrease of population in some of the cities of north Italy, notably Turin and Bologna ; and in most large towns except Rome and Naples the deaths exceed the births.

A decrease in population similar to that in the Alpine valleys of Piedmont (q.v.) may be noticed, also in those of Lombardy, e.g., the Valtellina. These valleys often have no through routes

and do not attract tourists as much as the corresponding French valleys.

The population of the different parts of Italy differs in char acter and dialect ; and there is little community of sentiment between north and south. Modes of life and standards of comfort and morality in north Italy and in Calabria are widely different; the former being far in front of the latter. Much, however, is ef fected towards unification, by compulsory military service, it being the principle that no man shall serve within the military district to which he belongs. In almost all parts the idea of personal loyalty (e.g., between master and servant) retains an almost feudal strength. The inhabitants of the north—the Piedmontese, Lom bards and Genoese especially—have suffered less than those of the rest of the peninsula from foreign domination and from the admixture of inferior racial elements, and the cold winter climate prevents the heat of summer from being enervating. They, and also the inhabitants of central Italy, are more industrious than the inhabitants of the southern provinces, who have hardly re covered from centuries of misgovernment and oppression, and are naturally more hot-blooded and excitable. The Sicilians and Sardinians have something of Spanish dignity, but the former are one of the most mixed and the latter probably one of the purest races of the Italian kingdom. Physical characteristics differ widely; but as a whole the Italian is somewhat short of stature, with dark or black hair and eyes, often good looking. Both sexes reach maturity early.

Births, Marriages, Deaths.

Birth and marriage rates vary considerably, being highest in the centre and south (Umbria, the Marches, Apulia, Abruzzi and Molise and Calabria) and lowest in the north (Piedmont, Liguria and Venetia), and in Sardinia. The death-rate is highest in Apulia, in the Abruzzi and Molise, and in Sardinia, and lowest in the north, especially in Venetia and Piedmont.

Taking the statistics for the whole kingdom, the annual mar riage-rate for the years 1876-80 was 7.53 per i,000; in 1881-85 it rose to 8.o6; in 1886-90 it was 7.77; in 1891-95 it was 7.41, and in 1896-1900 it had gone down to 7.14 (a figure largely produced by the abnormally low rate of 6.88 in 1898), and in 1925 was 7.42 (having been as high as 13.99 in 192o, 11•54 in 1921), and below 3 per i,000 in 1916-18. Divorce is forbidden by the Roman Catholic Church, and only 1,337 judicial separa tions were obtained from the courts in 1924, more than half of the demands made having been abandoned. Of the whole popu lation in 1901, 57.5% were unmarried, 36.0% married, and 6.5% widowers or widows, and in 1921 the figures were much the same, only 45,070 persons being noted as legally separated. The illegiti mate births show a decrease, having been 6.95 per Ioo births in 1872, 5.72 in 19o2 and 5 in 1925 with a rise, however, in the intermediate period as high as 7.76 in 1883. The birth-rate shows a corresponding decrease from 38.10 per i,000 in 1881 to 33.29 in 1902, 27.79 in 1925 and 27.2 in 1926. The male births are now about 6% in excess of the female, but there is a greater male mortality, so that, while in 1871 there was an excess of 143,37o males over females in the total population, in 1881 the excess was only 71,138, and in 1901 there were 169,684, and in 1921, 531,506 more females than males. The death-rate (excluding still-born children) was, in 1872, 30.78 per i,000; in 1899 it had decreased to 21.89, and in 1925 to 16.79. The excess of births over deaths varies considerably—in 188o it was only 3.12 per I,000 owing to a very low birth-rate, but has averaged about ii.o5 per i,000 from 1896 to 1925. In 1926 the total of births was 1,134,616, and in 1927 1,121,072 (4% still-born) ; the deaths were 680,074 and 631,897, giving natural increases of about 409,000 and 444,00o respectively. The influence of the war period will be seen in the subjoined table :— Emigration.—The movement of emigration before 1914 was divided into two currents, temporary and permanent—the former going chiefly towards neighbouring European countries and to North Africa, and consisting of manual labourers, the latter towards trans-oceanic countries, principally Brazil, Argentina and the United States. These emigrants remained abroad for several years, even when they did not definitively establish themselves there. There was a tendency towards increased emigration during the last quarter of the 19th century, owing to growth of popula tion, and the over-supply of and low rates of remuneration for manual labour in various Italian provinces.

In 1911 the Italians abroad numbered 5,500,000, including those who had emigrated long before that date but had retained their nationality, and whose children had declared themselves Italians. In the 4o years 1872-1913 emigration had effected a reduction of at least 3,800,00o persons in the natural increase of the popula tion of Italy. During the war the movement naturally slackened. Conscription, and the intense demand for man-power at home removed alike the possibility of and the incentive to migration. The total number of emigrants in the four years was, in fact, barely three-fifths of the pre-war annual average. With the return of peace began a feverish race abroad, which was at its height in 1920 when those who had returned from the United States during the war realized that if they delayed they might not be able to get back at all. The number of those repatriated in 1921– 22 amounted to about half the total number of emigrants, but in 1926 were not much more than a quarter. In all probability the proportion was formerly greater, since nearly all of those in Europe and about 55% of those overseas returned for the winter. Nevertheless, when a census of Italians abroad was taken in 1924 it was found that there were 9,910,676 of them scattered about the world. For statistics of the movement of population and the restriction of migration to the United States see MIGRATION.

The present stream of emigrants differs considerably from that of 1909-13 in respect of quantity and quality, countries of des tination and districts of origin. The restrictions introduced by the United States and other countries have not only reduced the total number of emigrants, but have tended especially to exclude the southern Italians. The number of Italian emigrants to the United States fell from 142,514 in 1921 to 52,182 in 1922, and in 1926 to 34,524.

It should be noted that Italian emigration into France—the only country to which they now go in at all considerable numbers, for not only the United States, but the Argentine Republic, Australia and Canada, have all stiffened their immigration laws— is carefully disciplined, the emigrants being formed into groups and subjected to supervision by the Italian consular authorities, with a view to the preservation of their pational character and civilization. The institution of the Fasci all' estero (see FASCISM) will undoubtedly tend to this end in all countries ; and it is quite clear that the absorption of the emigrants into the country which receives them is the last thing that Italy desires. Those Fascists, for instance, who do not send their children to Italian schools, where such are available, are to be expelled from the party; and they are required to wear the party badge, except where this is expressly forbidden by the laws of the country in which they are. Provision is made for the return of expectant mothers so that their children may be born in Italy.

See L'Emigrazione Italiana dal 1910 al 1923 (Rome, 1926) and L'Emigrazione Italiana regli anni 1924, 1925 (Rome, 1927).

Public instruction in Italy is regulated by the State, which maintains public schools of every grade, and requires that other public schools shall conform to the rules of the State schools. No private person may open a school without State authorization. Schools may be classed thus : I. Elementary, of two grades, of the lower of which there must legally be at least one for boys and one for girls in each commune ; while the upper grade elementary school is required in communes having normal and secondary schools or over 4,000 inhabitants. In both the instruction is free. They are maintained by the communes, sometimes with State help. The age limit is six to nine years for the lower grade, and up to 12 for the higher grade, attendance being obligatory at the latter also where it exists. 2. Secondary, instruction (i.) classical in the ginnasi and licei, the latter leading to the universities; (ii.) technical. 3. Higher education—universities, higher institutes and special schools.

Of the secondary and higher educatory methods, in the normal schools and licei the State provides for the payment of the staff and for scientific material, and often largely supports the ginnasi and technical schools, which should by law be supported by the communes. The universities are maintained by the State and by their own ancient resources ; while the higher special schools are maintained conjointly by the State, the province, the commune and (sometimes) the local chamber of commerce.

In education, as in other matters, the State, according to the Fascist conception of it (see FASCISM) must intervene from the very beginning. Boys from the age of five or six join the Balilla under the Opera Nazionale Balilla (Balilla was a boy, who, by throwing a stone at an Austrian, began the insurrection of Dec. 5-10, 1746, in Genoa), while girls are enrolled by the Opera Nazionale delle Piccole Italiane, and eventually pass to the women's Fasci. New text-books are to be written in order that the children may be brought up in the Fascist spirit, and all teachers who are found to be lacking in it are to be dismissed. A number of women teachers of boys' classes have already been weeded out. From the Balilla the boys pass, at 15, to the Avanguardisti, and, having previously received a semi-military training, at the age of 18, are qualified to take the oath of alle giance to the king and to Fascist principles and receive their rifles. Eventually, all young Italians will, so it is intended, pass through these stages; so that, when the young children of the present generation have come to maturity, citizenship and Fascism will be synonymous and conterminous, which they are at present far from being, as the Fascist party only numbers about a million members, and refuses to admit more of the older generation to its ranks.