Ivories of the Christian Era

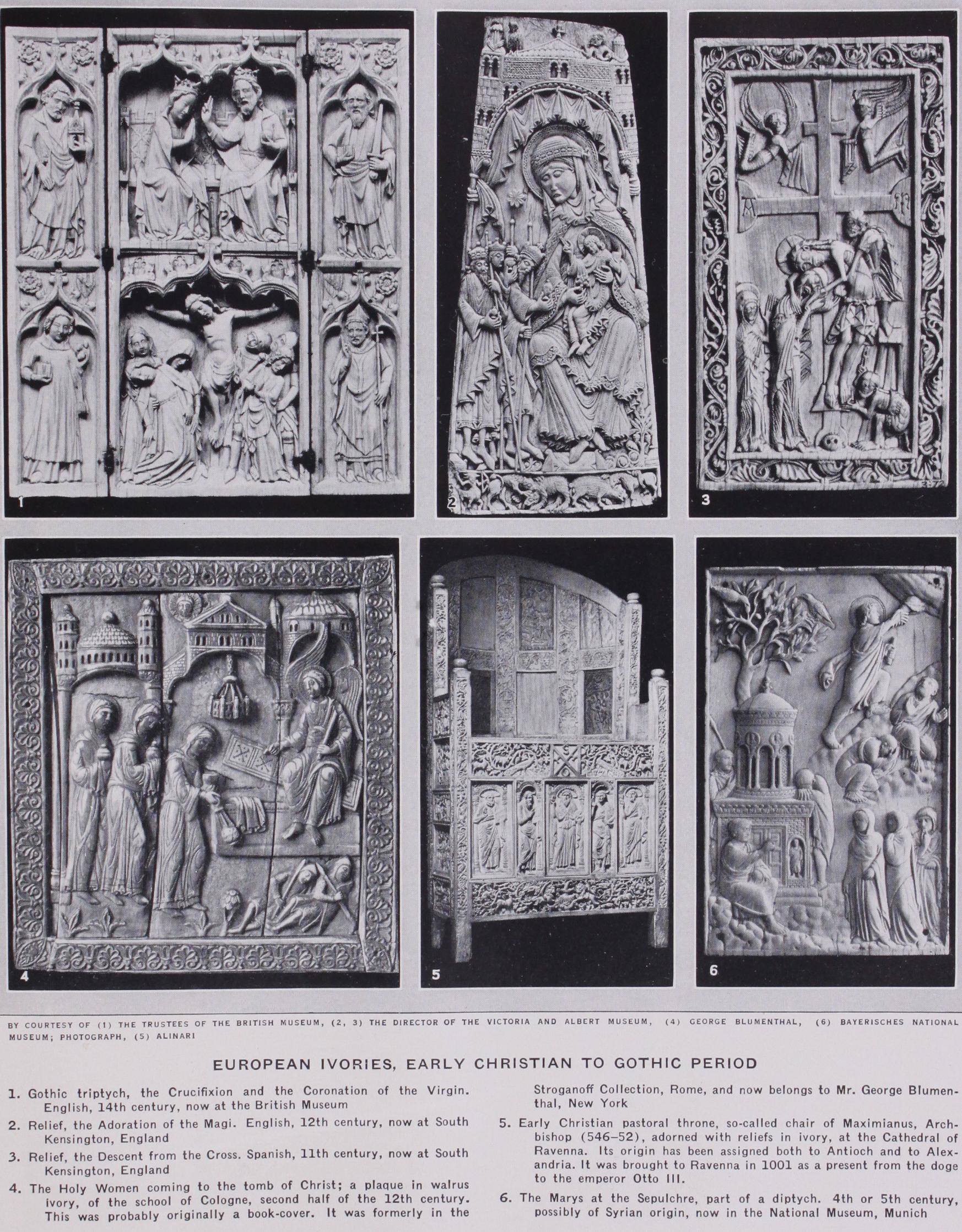

IVORIES OF THE CHRISTIAN ERA The ivory carvings of the earlier centuries of the Christian era show a close continuity in style with those of the preceding period, and much of the finest work, such as the well-known Symma chorum-Nicomachorum diptych in the Victoria and Albert and Cluny museums, may be called either late pagan or early Chris tian. The classification and provenance of ivories made between the 4th and the 7th centuries is one of the most difficult problems of Christian archaeology and to specify definitely the place of origin of individual examples is almost impossible. Intercourse between the great centres of Mediterranean civilization was so close that very similar cultural conditions existed in cities so far apart as Antioch, Constantinople, Alexandria and Rome. This culture represents a fusion of the plastic and naturalistic ideals of classic art with the abstract and colouristic principles of the East. Christianity was oriental in conception and while for its own purposes it took over many of the artistic forms of Paganism it was largely influenced by the ideals of the Aramaic art of the countries adjacent to Palestine. A number of the earliest ivories with definitely Christian subjects are frequently associated with Antioch, though we have no one carving which can with cer tainty be ascribed to the school. Such celebrated carvings as the Brescia reliquary, a very fine pyxis at Berlin, and the diptych or book-cover with scenes from the New Testament in Milan cathe dral, the first two of which may be assigned to the late 4th or early 5th centuries have been included in this group. The Milan book-cover has also been made the centre of a group of ivories which have recently been ascribed by several American scholars to Provence on the ground of their relationship with the Early Christian sarcophagi found in Southern France.

Other important carvings which have also been associated alternatively with Syria and with various western centres are the lovely reliefs of the Maries at the Sepulchre in the Trivulzio Collection at Milan and the Ascension of Munich. From the early centuries of the present era Alexandria was the seat of a flourish ing school of bone carvers who produced small reliefs, probably for the decoration of articles of furniture, carved with figures taken from classical mythology, similar to those employed on contemporary woven fabrics. To the same centre should probably be ascribed the important reliefs with Bacchus, a warrior and other figures, now on the pulpit at Aix-la-Chapelle, and a number of diptychs which show strong traces of Hellenistic influence, such as the diptych of a Muse and a Poet at Monza. A very individualistic series of carvings, dating from the 6th century, closely connected with Alexandria in iconography, are the reliefs (mainly distributed between the museums at Milan and South Kensington) which may be associated with the celebrated ivory chair of St. Mark formerly at Grado.

Another ivory chair (now at Ravenna) usually, though for no very definite reason, called the throne of Maximianus, has been assigned alternatively to both Antioch and Alexandria. With these carvings may be grouped several book-covers and a number of other ivories. Another group, dating in the main from the 6th century, for which a Palestinian origin is usually claimed, though recently an American scholar has brought forward evidence con necting it with Alexandria, may be centred round a book-cover in the museum at Ravenna, formerly at Murano. This group includes panels scattered among various collections and a number of pyxides. Both in iconography and style this group is purely oriental in derivation.

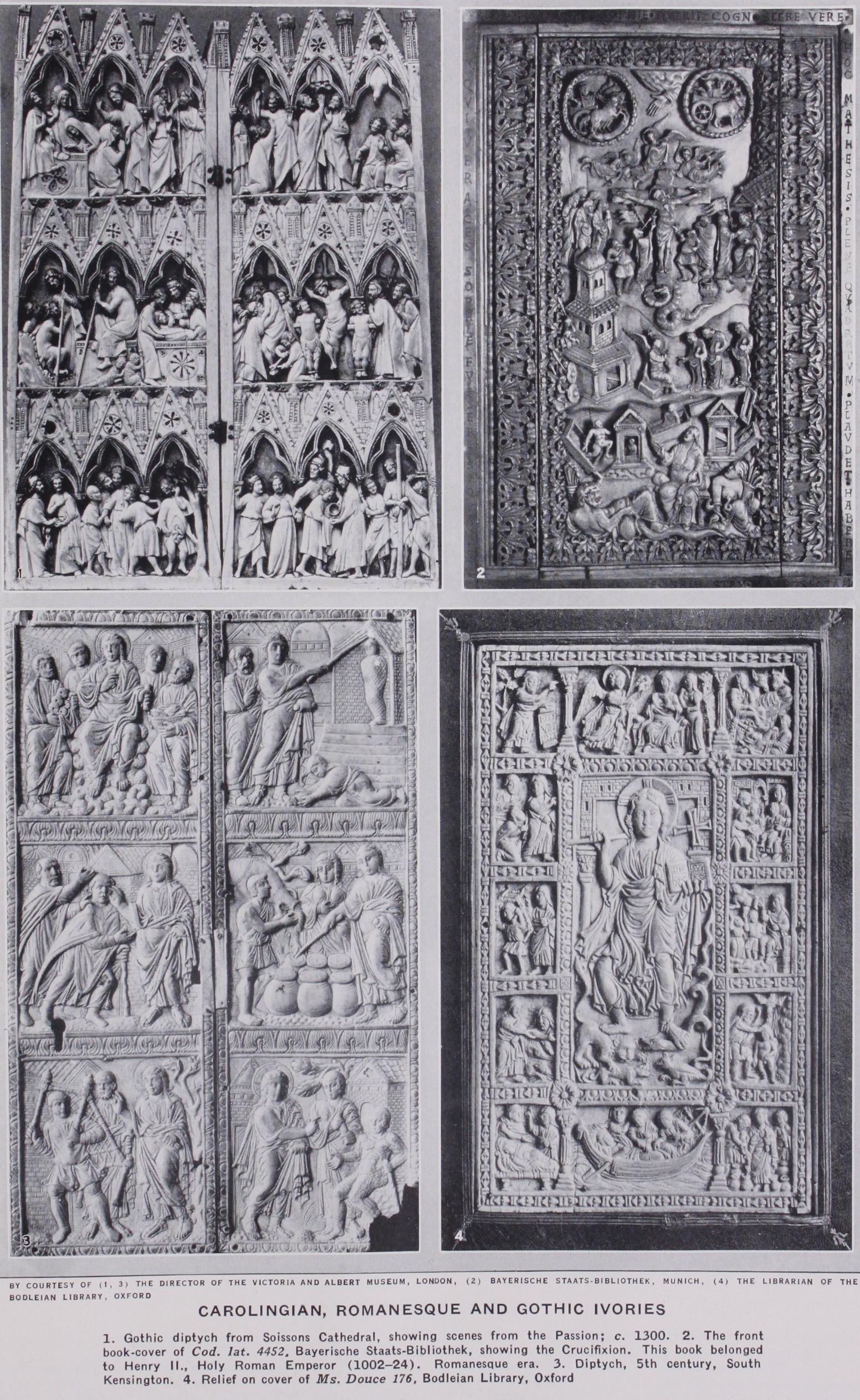

The art of the capital itself was, we may assume, very eclectic, and though there is no definite evidence several ivories, including the supremely fine relief of St. Michael in the British Museum, have been assigned to Constantinople. It is also possible that most of the consular diptychs were produced there, though there is also evidence connecting them with Alexandria. A very large proportion of the ivory-carvings of this period were in the form of diptychs. In their simplest form these consisted of two leaves, the insides hollowed out and coated with wax on which a message could be scratched with the sharp end and effaced with the blunt end of a stylus. The unprepared ivory could also be used for receiving ink. Diptychs of an elaborate and purely cere monial character, carved on the outside, were apparently used as presents to commemorate marriages or other family or official events; but the greater number that have been preserved are associated with consuls of Rome or Constantinople and were made for the purpose of notifying, to the emperor, or others, the sender's appointment to the consulate. These were more or less richly decorated according to the rank of the recipient, elaborate com posite examples, such as the Barberini diptych in the Louvre, having been probably made for the Emperor.

These ceremonial diptychs date from the 4th or the beginning of the 5th century and between 6o and 70 are known to be in existence (in whole or in part) ; of these, about 5o are consular, the series ending with the year 541 when the office was abolished by Justinian. The diptychs in great part owe their preservation to the fact that at a later period they were frequently transformed into book-covers. Diptychs with Christian subjects are rare, though there is a fine 5th century example at South Kensington, with six of the miracles of Christ, which is allied in style with some of the earlier pagan examples. By the 5th century a liturgical use of diptychs seems to have been established in the church ; names of those for whom prayers were asked were in scribed on the insides of the leaves and solemnly recited during the mass. With the end of the 6th century there is an almost com plete blank for nearly two centuries in the history of ivory-carving in the eastern empire as well as in the west.

Byzantine Ivories.—The iconoclasts during the disputes of the 8th and early 9th centuries strove to substitute a secular and purely ornamental style for the religious and representational art of the monastic party and it is to this fact that we owe the group of caskets with subjects largely drawn from classical mythology or with zoomorphic decoration. The dating of these caskets has been much discussed but it is probable that the earliest and finest, such as the casket from Veroli now at South Kensington, were produced during the iconoclastic period, though it seems likely that those of rougher workmanship are rather later in date while others again are apparently western imitations. Similar caskets with sacred subjects, usually the story of Adam and Eve, as for instance the example at Cleveland, appear from their style to date from the nth or 12th century. The main period of Byzan tine ivory-carving begins with the cessation of the iconoclastic disputes in 842 and it is probably to the period between the loth century and the sack of Constan tinople in 1204 that most of the surviving ivories belong, though it is not impossible that some should be ascribed to the suc ceeding centuries.

Ivory-carving occupies an ex ceptional place in Byzantine art of this period, there being prac tically no monumental sculpture in existence, but the difficulty of dating the ivories is greatly in creased by this fact. Almost the only ivory the date of which can be fixed with any certainty by external evidence is the fine re lief, in the Bibliotheque Nation ale, Paris, of Christ crowning the Emperor Romanus and his wife Eudocia; this may be dated about 945, to which period should be assigned such a masterpiece as the Harbaville triptych in the Louvre. Only slightly later probably is the magnificent re lief of the Vi. gin and Child now at Cleveland, formerly in the Stroganoff collection. An early group apparently is that in which the figures are sharply cut in high relief and show the same tightly curling hair as on the caskets. The finer carvings such as these show an austere beauty of conception and a refinement and careful precision of finish that is a legacy of the classical tradition, but the minor work suffers from a monotony of design and a carelessness of execution which become very tedious.

Mohammedan Ivories.—A group of ivories, the dating and origin of which are very uncertain, are the oliphants or horns. Some of the earliest of these perhaps go back to the iconoclastic period and some, for example the horn in the cathedral of St. Veit at Prague, which has representations of scenes in the Hippo drome, may have been made in Constantinople. But the greater number are carved with hunting scenes or zoomorphic decoration, and while some of these are probably western copies, most of them are apparently of Syrian or Mesopotamian origin, the ani mals and monsters with which they are ornamented being similar to those common on Asiatic textiles. One of the finest of the horns with hunting scenes is in the minster at York.

Another series of ivories, the ornament of which is derived from oriental sources, is a group of caskets carved, as their in scriptions show, in the loth century for the court of the caliphs of Cordova, one of the most important artistic centres in Europe at this period. The compositions of figures, animals and birds carved among foliage scrolls seem to derive from Mesopotamia. With the same country have been associated a rather later series of caskets painted with interlacing scrolls, foliage and figures of birds, animals and men; it is, however, more probable that they were produced in Sicily by Arab artists.

Carolingian and Romanesque Ivories.—Ivory-carving occu pies an unusually important position in the history of the artistic revival during the 9th and loth centuries under the Carolingian emperors, for monumental sculpture of the period is almost non existent in Western Europe during the period between the expiring classical tradition and the Romanesque revival of the latter part of the I I th century. It is usual to include with the carvings produced within the empire of Charlemagne's successors those done in western Germany under the Ottonian emperors (936 1002), as both belong to a common stylistic origin. These ivories have recently been divided into three main groups. The earliest of these, known as the Ada group from its relationship to a manuscript of the Gospels at Treves illuminated for the Abbess Ada, sister of Charlemagne, about A.D. 800, has been located in various centres in the middle Rhine and Moselle districts. Most of the carvings of this group are closely based on early Christian models.

The second or Liuthard group is associated with an ivory relief on the binding of a psalter in the Bibliotheque Nationale at Paris written by Liuthard for Charles the Bald not long after 87o. This group has been localized in the Amiens or Rheims districts and should probably in any case be ascribed to the north-east of France. The style appears to have been influenced by some such manuscript as the celebrated Utrecht psalter, the figures being characterized by the same rather slender proportions and energetic action. Some of the carvings of this group, such as the fine book cover in the National Library at Munich, have points of re semblance with the Byzantine caskets of the Veroli type men tioned above and as many of the reliefs may be assigned to the second half of the 9th century they have an important bearing on the dating of the caskets. A casket at Berlin obviously modelled on a Byzantine prototype is dated by Dr. Goldschmidt about 90o.

A number of ivories belonging to the third group can be associ ated with the district of Metz from an early period, as for instance the reliefs on the cover of the sacramentary of Drogo, bishop of Metz, from 826 to 855, now in the Bibliotheque Nationale at Paris. The carving is usually in lower relief and the forms heavier than those of the Liuthard group. There are of course a number of other ivories mostly of a date rather late in the period which do not fall into either of these groups. The district of the lower Rhine, and Cologne in particular, was one of the chief centres of Romanesque ivory-carving in the i 2th century. Among the ivories produced in this district is an important series of large reliefs in walrus tusk probably part of an altar-piece with scenes from the Life of Christ, two of which are in the collection of Mr. Blumenthal at New York and the remainder at South Ken sington. Ivories for secular use, practically non-existent during the Carolingian period, reappear principally in the form of gaming pieces. The draughtsmen are usually of Rhenish origin, but chess-pieces appear to have been made in France as well as in the North, and some of the most famous, found in the island of Lewis off Scotland, are probably of Scandinavian, or possibly of British, origin.

A number of carvings of very high artistic quality were pro duced in England in the i ith century, and one very distinctive group may be associated with the famous Winchester school of illumination. The well-known whale's bone relief at South Ken sington with the Adoration of the Magi, has been ascribed alter natively to northern France or Belgium, but the balance of evi dence is certainly in favour of an English origin. To England may also be ascribed a crozier head and a number of tau crosses of exceptional beauty at South Kensington and the British Museum, decorated with figure subjects and foliage scrolls. In Italy ivory-carvings of the Romanesque revival take a different form, derived closely in style and iconography from the Early Christian and Byzantine tradition. The famous ivory "paliotto" at Salerno forms the centre of a large group of carvings being based on an Early Christian model.

Spanish ivories of the 11th and 12th centuries, on the other hand, show a mixture of Moorish and Northern influence. They are closely allied to the contemporary manuscripts and seem to have been produced mainly in the north in Castile and Leon, one of the most famous, the shrine of San Millan de le Cogolla, being still preserved in the cathedral of that name. Others are in the Madrid museum, in the cathedral at Leon and at South Kensington.

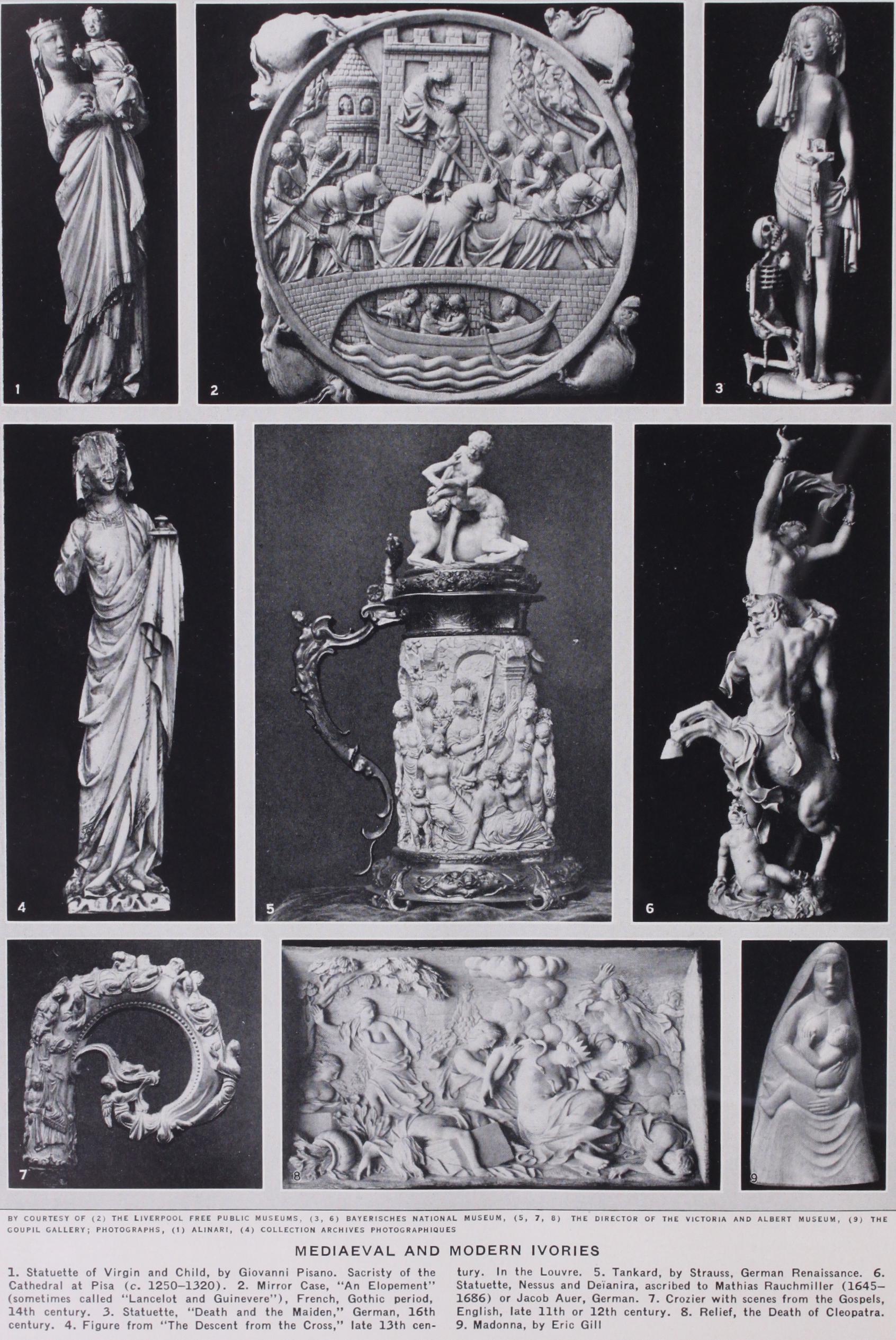

Gothic Ivories.—From the great period of French Gothic monumental sculpture—the first half of the 13th century—there exist only a few isolated examples of ivory-carving, some of the most notable being a group of statuettes of the Virgin and Child and the magnificent crucifix at Herlufsholm in Denmark. But to the last half of the century must be ascribed some of the finest examples of Gothic ivory-carving, among them the groups of the Coronation of the Virgin and the Descent from the Cross in the Louvre. To the end of the same century belong a number of diptychs and triptychs with scenes from the Passion which may be associated with a very fine diptych at South Kensington, said to have come from Soissons. Another series belonging to the 14th century is a group of polyptychs in the form of small domestic altarpieces or tabernacles usually with statuettes of the Virgin and Child under a canopy with, on the wings, scenes from the New Testament. A third group of carvings, formerly described as English, is distinguished by bands of "roses" divid ing the subjects; these reliefs show greater variety both in indi vidual types and iconography than is found in the crowded scenes of another group of diptychs with scenes from the Infancy and Passion, mostly dating from the second half of the century.

Besides these main groups there are a host of small diptychs and plaquettes with one or more scenes on each leaf. Apart from the long sequence of statuettes of the Virgin and Child, which extends from the early 13th century to the end of the period, the best of which are of almost incomparable loveliness, there are comparatively few figures or groups and, though there is docu mentary evidence that crucifixes were made in great numbers, they have perished almost without exception. Ivory was a favour ite material for pastoral staves and great ingenuity is shown in fitting in two subjects, generally the Virgin and Child with angels and the Crucifixion, back to back in the volute. Large altarpieces were also made, though no complete example has survived; these were composed of groups carved in high relief usually with scenes from the Passion, in architectural settings apparently mounted on coloured backgrounds of metal, wood or marble. The fine relief of the Maries at the Sepulchre at South Kensington is a good example of one of these groups.

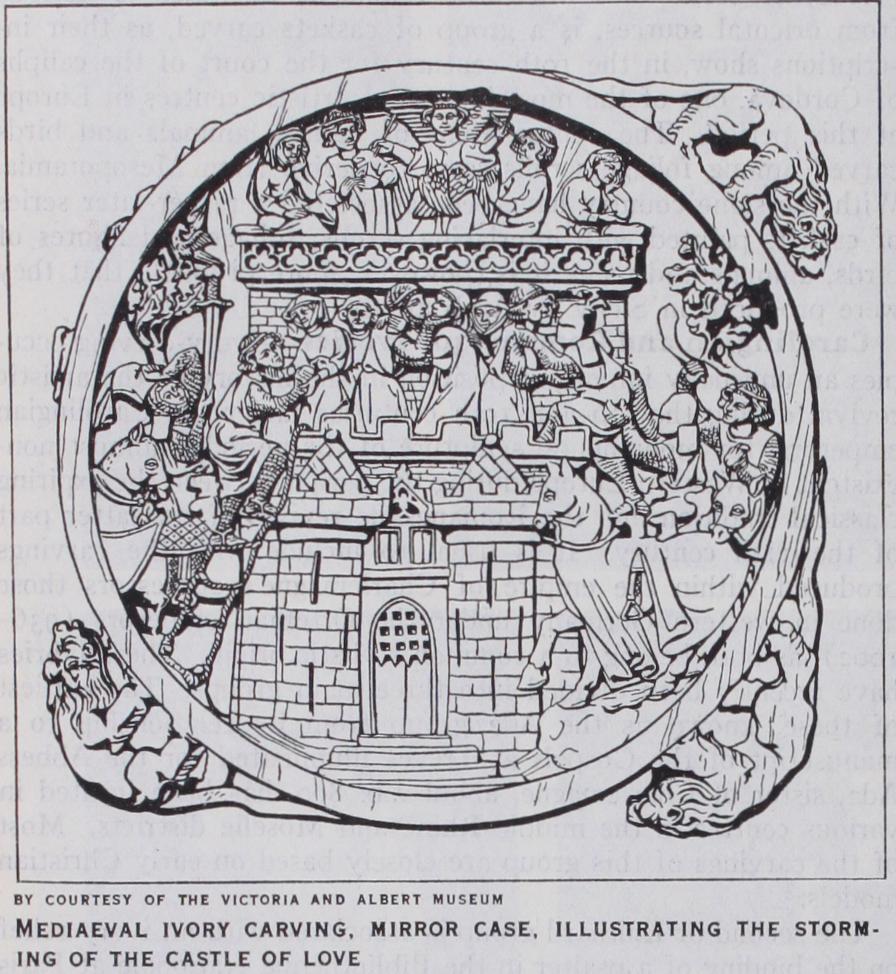

There is a great increase at this period of ivories for domestic and civil use ; caskets, mirror cases, combs, writing tablets were made in great quantities for export as well as for use at home. On these were usually depicted charming little scenes of love making, or episodes drawn from the popular romances of the period, one of the finest examples of the mirror cases being that with a story of an elopement (sometimes called Lancelot and Guinevere) now at Liverpool. The reputation of ivory-carving of the Gothic period has suffered from the superabundance of the material, the great majority of the minor carvings being little better than tradework. After the middle of the 14th cen tury there is a rapid decline in the quality of the work and the ivories produced, chiefly in northern France and Belgium, during the 15th and early i6th centuries are of little artistic importance. These consist mainly of Paxes, mementi mori and small objects of devotion.

The rare ivories which can be ascribed to Germany in the 14th century are such close imitations of French work that they are hardly worthy of special mention. The case of England is rather different, in that not many carvings have survived but these are very individual and usually of fine quality, less elegant but more monumental in character than contemporary French examples. Work such as the well-known diptych of Christ and the Virgin and Child or the statuette of the Virgin and Child at South Kensing ton, or the two triptychs associated with Bishop Grandisson, in the British Museum, show that work of real beauty was produced outside France.

Of Italian ivory-carving of the 14th century the lovely statuette of the Virgin and Child by Giovanni Pisano in the cathedral at Pisa and a few crucifix figures, notably the fine fragment at South Kensington, are among the few survivors. The Embriachi family and their assistants produced at the end of the 14th and during the earlier part of the 15th centuries in northern Italy a quantity of caskets, triptychs and some large altarpieces in which narrow strips of bone, placed side by side, are associated with mounts of intarsia of coloured woods and ivory. This work has no great artistic value, though it has at times a sumptuous decorative effect.

Only a few scattered examples of i6th century work remain, such as the fine figure of St. Mary Magdalene in the Metropolitan Museum at New York or the Virgin and Child statuette in the Louvre, both French in origin, or again the very individual Ger man statuette of Death and the Maiden at Munich. In the 17th and 18th centuries Germany and Flanders appear in the fore front as centres of ivory-carving and the finest work of the period still remains in German and Austrian museums. For the first time ivory-carving ceases to be anonymous, we have a few carvings signed by definite artists and there is evidence that sculptors such as the Italianized Fleming Francois Duquesnoy Fiammingo), Algardi and Leonard Kern, among others, worked in ivory. The influence of Rubens is very apparent in much of the carving of the period, especially in the large tankards with Bacchanalian groups and there are records that his pupil, Lucas Faidherbe, did a number of carvings from his master's designs. Two other Flemish carvers were famous for their bacchanalian groups of children, Gerhard van Opstal and Il Fiammingo mentioned above.

In Germany Christoph Angermair, who in the first half of the 17th century made the celebrated coin cabinet at Munich, was succeeded by a number of artists who produced a vast amount of work which, though frequently exhibiting high tech nical ability, shows little originality either in subject or treat ment. The statuettes and groups of naked gods and goddesses, which form an appreciable proportion of the carvings, are mainly inspired by the antique or from the work of Late Renaissance and Baroque sculptors such as Giovanni Bologna and Bernini. The work of Ignaz Elhafen (born before 1685, died before 1725), one of the ablest sculptors of the period, is best seen at Mu nich ; other characteristic works in the same manner are an elabo rate group of bacchanals at Vienna ascribed to Mathias Rauch miller (1645-1686) and a fine group of Nessus and Deijanira at Munich ascribed to Rauchmiller or Jacob Auer, a South Ger man working in the first half of the i8th century. Statuettes of saints, Christ at the Column and Crucifixion groups were also popular as well as reliefs with scenes from the New Testament ; and it is to the 17th, and more especially to the i8th century, that we owe the figures of Christ on the Cross, which appear to have been carved all over Europe and examples of which exist in nearly every collection.

A characteristic feature of the period is the development of interest in portraiture from the large equestrian groups ascribed to Steinle (died 1727) at Vienna to the small portrait medallions by Jean Cavalier and Le Marchand (1674-1726). A peculiarly German type of work of the i8th century is the association of ivory with wood, the principal exponents of which were Simon Troger, Veit Grauppensberg and others. Another group which must be mentioned is that of turned ivories produced mostly in the neighbourhood of Nurnberg by the Zick family. Other who excelled in this ingenious form of craftsmanship were M. Heider, Spengler and others.

In Italy ivory-carving follows similar lines as in Germany but almost the only artist whose work remains to us in any quantity (mostly at Munich) is Antonio Leoni who, in the first half of the i8th century, produced reliefs and statuettes in style very akin to that of Elhafen. In Scandinavia Magnus Berg (1666-1739) is responsible for an enormous output of rather uninteresting carvings, mainly reliefs with allegorical and mythological subjects.

The still surviving branch of the industry established at Dieppe in the I 7th century, chiefly for the production of crucifixes and objects of devotion, is of relatively small artistic importance. Spain and Portugal too produced little original work of impor tance and, though the amount is considerable, the work turned out in the Portuguese colonies, chiefly Goa, is on an even lower level.

The Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries.—In the early 19th century the interest in portraiture and the classical revival both find ingenious expression in the work of Benjamin Cheverton ( 1794-1876) who made with the partial aid of a machine reduced copies of marble busts, statuettes and reliefs. During the later part of the century, especially in Belgium, many sculptors inter ested themselves in ivory-carving, frequently associating it with other materials but this phase hardly calls for lengthy notice. In recent years there has been a distinct revival and some good work, chiefly for ecclesiastical use, has been produced.

Forgeries.

Another less praiseworthy phase of modern ivory carving must be noticed, that of forgeries. Few materials lend themselves to such successful imitation and it is not beyond the power of a clever craftsman to so patinate, rub and colour the ivory as to make it almost indistinguishable from a genuinely old carving. The crackle of genuine age is rather more difficult to simulate and a regular network of cracks across the grain may raise suspicions, though even these are not always justified, natural crackle being very variable. The forger fortunately usually gives himself away in details of iconography and a general feeling of style; but the detection of both these points is a question of expe rience and long familiarity with and actual handling of genuine work. (See also IVORY CARVING : Chinese; IVORY CARVING : Jap anese; IVORY CARVING: North American.) BIBLIOGRAPHY.-General: W. Maskell, Ivories Ancient and Medi aeval in the South Kensington Museum (1872) ; J. 0. Westwood, Fic tile Ivories in the South Kensington Museum (1876) ; E. Molinier, His toire generale des arts appliqués a l'industrie, I. "Les lvoires" (1896) ; E. Molinier, Musee national du Louvre, Catalogue des ivoires (1896) ; W. Voge, "Elfenbeinwerke," Die Konigliche Museen zu Berlin, Be schreibung der Bildwerke der christlichen Epochen (2nd ed. 1900-02) ; A. Venturi, Storia dell' arte italiana (Igo') ; A. M. Cust, Ivory Workers of the Middle Ages (1902) ; J. Destree, Musees Royaux des Arts Deco ratifs et Industriels, Catalogue des ivoires (1902) ; R. Kanzler, Gli avori dei Musei profano et sacro della Bibliotheca Vatican (1903) ; Michel, Histoire de Fart (1905) ; A. Maskell, Ivories ('905) ; 0. M. Dalton, Catalogue of the Ivory Carvings of the Christian Era in the British Museum (1909) ; W. F. Volbach, Die Elfenbeinbildwerke, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin; Die Bildwerke des Deutschen Museums (1923) ; 0. Pelke, Elfenbein (1923) ; M. H. Longhurst, English Ivories (1926) ; Cambridge Ancient History and Cambridge Mediaeval History; R. Berliner, Catalogue des Bayerischen National-Museums, "IV. Abteil ung: Die Bildwerke in Elfenbein und Steinbockhorn" (1926). M. H. Longhurst, Victoria and Albert Museum, Catalogue of Carvings in Ivory, pt. I., "Up to the 13th Century" (1927). Prehistoric: Abbe Breuil in Revue Archeologique, 4th Series XIII., 1909 pp. seq.; R. A. S. Macalister, Text-books of European Archaeology, "I. The Pale olithic Period" (1921) ; British Museum, Stone Age Antiquities (1926) ; J. Dechelette, Manuel d'archeologie prehistonique (1908) ; S. Reinach, Repertoire de Part quaternaire (1913) ; M. Hoernes, Urgeschichte der Bildenden Kiinste in Europa (1915). Egypt: J. Capart, Primitive Art in Egypt (1905) ; W. M. Flinders Petrie, Nagada and Ballas (1896) and Abydos, pt. II. (1903) ; Quibell and Green, Hierakonpolis, pt. I. (190z). Babylonia and Assyria: Andrae, Die archaischen Ischtar-Tempel in Assur (1922) ; British Museum, Guide to the Babylonian and Assyrian Antiquities (1908). Aegean, etc.: F. Poulsen, Der Orient und die friih griechische Kunst (1912) ; H. R. Hall, Aegean Archaeology (1915) ; British School at Athens, Annual, xxv. (1921-23) ; British Museum, Excavations in Cyprus, by A. S. Murray and others (1900) ; British School at Athens, Annual, xiii. (1906-07) ; British Museum, Excava tions at Ephesus, by D. G. Hogarth and others (1908) ; Greek and Roman: H. Graeven, Antike Schnitzereien ('903) ; R. Delbriick, Die Consulardiptychen und verwandte Denkmaler (1926 et seq.) ; E. Capps, "The Style of the Consular Diptychs," Art Bulletin, pp. 1 seq. (1927). Early Christian and Byzantine: A. F. Gori, Thesaurus veterum dip tychorum (1759) ; R. Garrucci, Storia dell' arte cristiana (1872-78) ; G. Schiumberger, L'Epopee byzantine (1896-1905) ; H. Graeven, Friih christliche und mittelalterliche Elfenbeinwerke aus Sammlungen in England (1898) ; H. Graeven, Friihchristliche and mittelalterliche Elfenbeinwerke aus Sammlungen in Italien (1900) ; J. Strzygowski, "Koptische Kunst," Catalogue general des antiquites egyptiennes du Musee du Caire (1904) ; D. Cabrol, Dictionnaire d'archeologie chre tienne (19°7 et seq.) ; 0. Wulff, Die Konigliche Museen zu Berlin, Be schreibung der christlichen Epochen. "III. Altchristliche und mittelalterliche Bildwerke" Teil I. (1909) ; C. Diehl, Manuel d'art byzantin (new ed., 1925) ; 0. M. Dalton, Byzantine Art and Archae ology (191I) ; 0. Wulff, Handbuch der Kunstwissenschaft, "Altchrist liche und Byzantinische Kunst," i., ii. (1914-18) ; E. B. Smith, EarlyChristian Iconography (1917) ; 0. M. Dalton, East Christian Art (1925) ; H. Peirce and R. Tyler, Byzantine Art (1926). Mohammedan: G. Migeon, Manuel d'art musulman (new ed., 1927) ; E. Kuhnel, Maurische Kunst (1924) ; E. Diez, Jahrbuch der Koniglichen Preus sischen Kunstsammlungen, xxi., xxxii. (1910—II). Carolingian and Romanesque: A. Goldschmidt, Die Elfenbeinskulpturen aus der Zeit der karolingischen und siichsischen Kaiser, i.—iv. (1914-23). Gothic: R. Koechlin, Les ivoires gothiques francaises (1924). Renaissance and later: C. Scherer, Elfenbeinplastik seit der Renaissance (1903) ; A. Julius, Jean Cavalier (1926) ; A. Milet, Ivoires et Ivoiriers de Dieppe (1906). (M. H. L.) History.—Ivory has always been an important medium of ex pression for Chinese carvers, and many exquisite examples of their work have come down to us, though their names are rarely known. Chinese ivory carvers have generally had a greater ap preciation of the intrinsic value of the material for their work than the carvers of Japan. An abundant supply and close intimacy with this material have doubtless helped to foster this appreciation among Chinese carvers, whereas the paucity of the supply and something in the Japanese character which was happier when carving wood, together with differences in certain phases of their culture, have prevented the higher development of ivory carving in Japan, though some excellent works have been produced. The former existence of elephants on Chinese soil is authenticated by linguistic, pictographic, historical, as well as archaeological evi dence. The Tso Chwan •(548 B.c.) records that the elephant has tusks which lead to its destruction owing to their use as gifts, and there are also a number of other references showing that ivory was taken as tax and brought as tribute to China and was greatly valued in early times. It came next to jade and was used as a mark of luxury for various purposes. Even articles such as pins for scratching the head, and the tips of bows, were made of elephant ivory in early Chinese antiquity. A 3rd century B.C. minister of State, Mong Ch'ang-Kiin, famous for his extravagance, possessed an ivory bed, which he presented to the prince of Ch'u. Ivory was used for personal ornament from time immemorial, and as early as the Ch'u dynasty (1122-247 B.c.) chopsticks were made of it and it was used to decorate the principal parts of some of the emperor's chariots. Later it became fashionable as a decora tion on the palanquins of important officials. Narrow memoran dum tablets or hu of ivory, originally used at court by princes and high officials, later a mere symbol of rank and an indispensable accessory to ceremonial dress, were articles of great importance. Examples of ornamental ivory carving with angular, spiral, geo metrical and floral designs, dating back to the Ch'u period, have come down to us.

In time the demand for ivory outgrew the native supply and large quantities of tusks had to be imported from Siam, Burma and India, which were described as long and large, and from An nan, which were small and short, as well as a variety yielding a red powder when cut by a saw which was pronounced to be of excel lent quality. As early as the i 2th century the Chinese knew that African ivory was the best. From the early i4th century at least the ivory from a slain elephant was esteemed the best; that taken not too long after natural death came next, while tusks discovered long after the elephant's death were least esteemed be cause the ivory was dull and opaque, and irregularly speckled.

Uses.—The Chinese cultured classes had always appreciated articles made of ivory, and ivory carving received imperial atten tion. In 1263 a bureau for carving in ivory and rhinoceros horn was established with some 15o craftsmen and an official in charge, and couches, tables and chairs, various implements, and orna ments for girdles inlaid with ivory and horn were made for the imperial household. In 168o the emperor K'ang Hsi established Tsao pan chu, or imperial ateliers covering 27 branches of indus try, including one for ivory carving, within the palace at Peking, and practical craftsmen from all over the empire were here brought together to produce fine work. They were in existence for over 1 oo years, turning out large numbers of excellent works bearing the stamp of the artistic fervour of the age. Authentic pieces from this imperial ivory carving atelier may be hard to identify, but many which exist in museums and private collections may reason ably be credited to it by reason of their superior workmanship which often reveals a marvellous quality of technical skill and harmonious beauty.

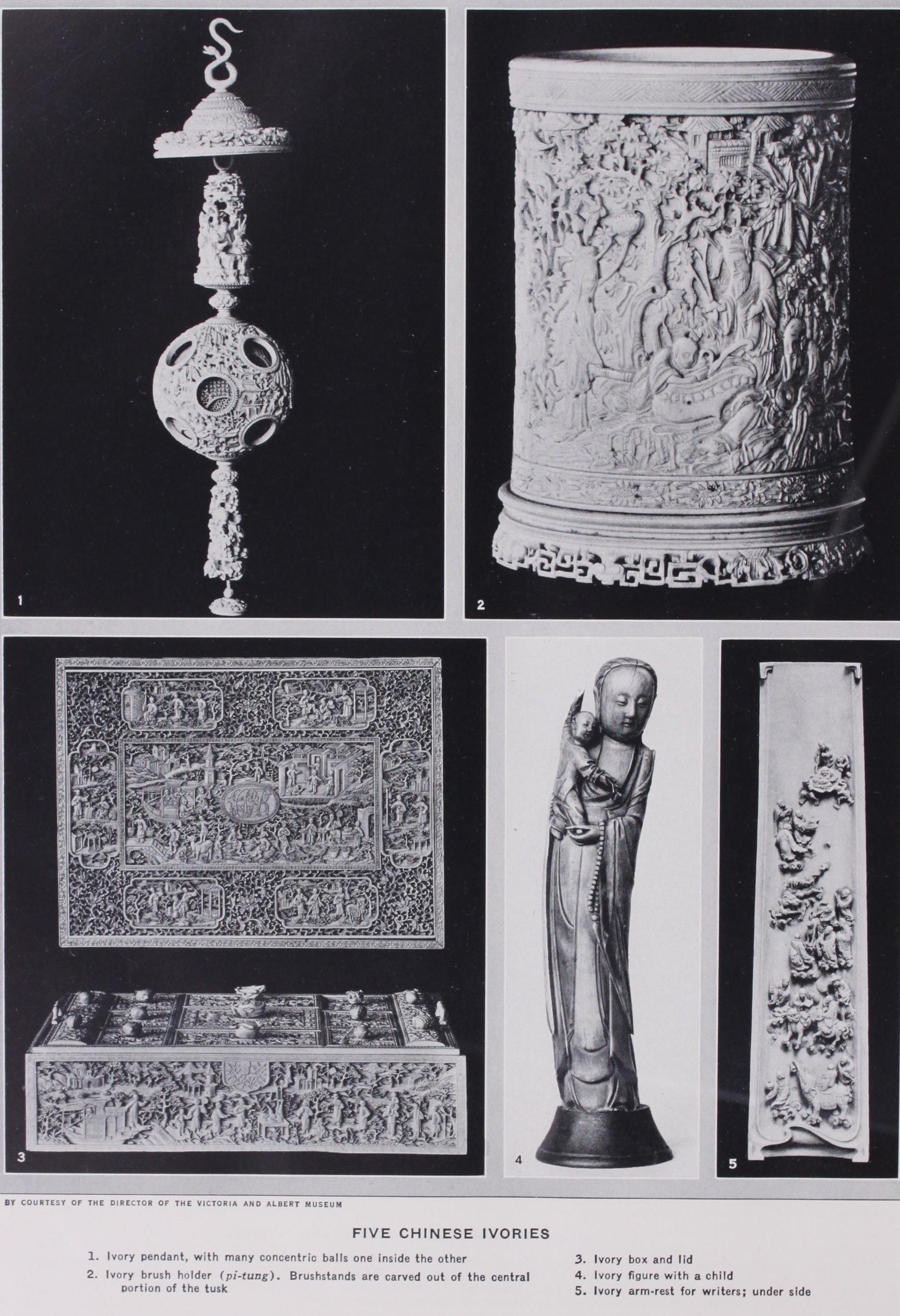

Great ingenuity is often displayed in the delicate workmanship of such an article as a fan, which may be made of finely cut plaited ivory threads, overlaid with carved flowers and birds, held by firmer pieces, likewise of carved ivory, having exquisitely carved and incised designs, which form the rim and the handle. Even more wonderful in their technical achievement as ivory carvings are the concentric spheres made in Canton as early as the 14th century and known as "devil's work balls," which are still being produced there. Endless patience and toil are needed to produce such concentric balls, carved one within the other, each having the most delicate patterns in pierced work. Models of palaces with carved roofs and intricate screens, peopled by tiny figures, and surrounded by trees and walls, all of ivory, were also a speciality of Canton ; but most of them are known for their technical rather than their aesthetic triumphs as ivory carvings. Chinese ivory carving, however, is by no means wholly represented by these minutely and elaborately carved works, though for more than a century China has catered to foreign taste in producing this line of work. Excellent pieces of high artistic value are often found among carved religious and philosophic figures, especially those of Kwan-yin, Goddess of Mercy, with her graceful form and flowing robes, and of the Arhats, with their beatific expressions.

Fine artistic work is also to be found in some of the brush holders (pi tung), which are often covered with a landscape in relief enlivened by figures; and in the arm-rests likewise designed for the scholar's table, and in snuff bottles which are often dyed and then carved so as to bring out the unstained ivory beneath— a technique known in Japan under the name of bachiru, where examples of it are to be seen among the 8th century relics now preserved in the imperial treasure-house, ShOsoin. Works of no common talent are also frequently found among girdle pendants, covers for cricket-gourds, and ivory plaques in relief used as insets on carved wood or lacquered screens and cabinets. Other articles for which the Chinese have used ivory as a favourite material as ornament, in various degrees of elaborateness, are the handle and sheath of the writing brush, trays, cages for crickets and birds, implements for opium smoking, toilet articles such as combs, small boxes, and pieces for various games. The Chinese, in the course of their history, have utilized the ivory of the ele phant, the mammoth, the walrus and the narwhal, the last three having been used as substitutes for the first. Ivory carving in one form or another is still an important industry in Canton, Peking, Shanghai, Amoy and Suchow, large numbers of carvings being produced for the foreign market.

See B. Laufer, Ivory in China (5922) ; S. W. Bushell, Chinese Art (2 vols., 1919-21).

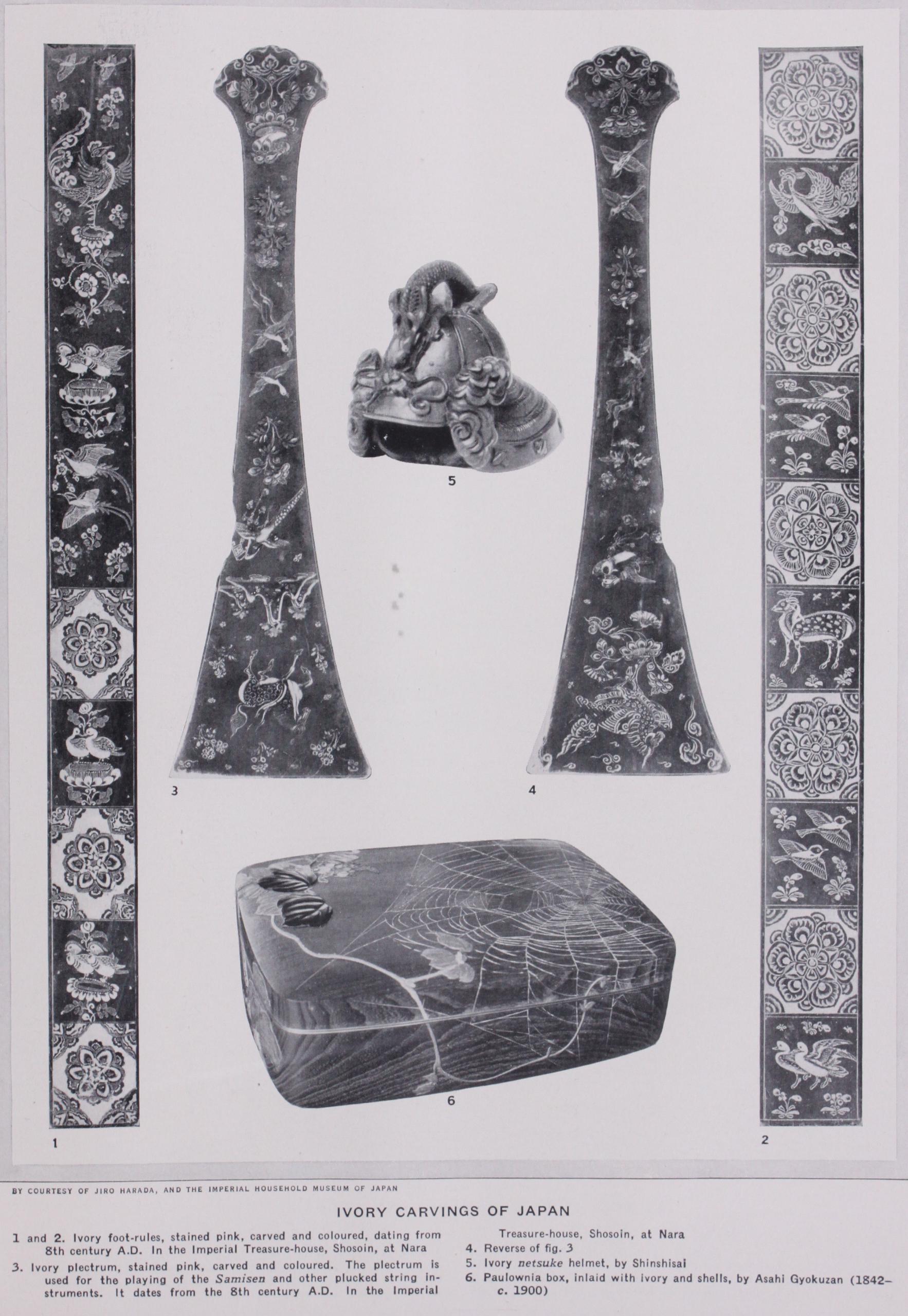

the ShOsoin (imperial treasure-house at Nara) collection, which consists mainly, if not entirely, of objects dat ing from the 8th century A.D., still housed in the original wooden structure, there are a number of ivories carved in the style known as bachiru. The name implies the method of decorating an ivory object in which an article with a finished surface is generally dyed or stained, and then designs are carved on it, the unstained parts, wherever the carving is deep, being either left plain or treated with other colours, producing a very beautiful and decorative effect. In some articles the carving is done on unstained ivory and colours are applied to the designs carved. In that unique collection there are several ivory foot-measures in blue and bright red, an ivory plectrum of bright red colour for the biwa (a stringed musical instrument), a large number of bright red and blue ivory go (a game resembling chess) pieces, a few ivory knife-hilts and several ivory scabbards, etc., which are all decorated in the bachiru style with minute carvings of birds, animals, flowers, etc., the colours still retaining their original freshness. Not only those so decorated, but a number of plain ivory pieces of sceptres, combs, flutes and foot-measures, are also found in that collection. Though ivory must have been im ported into Japan, it was used extensively with horn, bone and wood in minute inlaid works, such as decorated go boards, arm rests, musical instruments, and various small boxes preserved in that treasure-house belonging to the imperial household of Japan.

For nearly ten centuries after the Tempyo period (708-781), to which most of the articles mentioned above belong, nothing is known about ivory carving in Japan, there being left practically no examples worthy of note from an artistic standpoint. It was Yoshimura Shuzan of Osaka who first began in the Kyoho era (1716-36) carving ivory netsuke (ornamental pieces fastened to the cords attached to a tobacco pouch, purse or inro; i.e., medicine case) which became very popular among the people. Of course, the wooden netsuke was already known to have been used with a bunch of keys in the Ashikaga period (1394– '573) and with inro, when they came to be a great fashion in the Tensho era (1573-92). However, Shuzan seems to have popularized them in ivory, and he was followed by many artists who carved mostly netsuke and rarely okimono, or ornaments for the alcove, in ivory as well as in wood. Among the ivory carvers who worked under the Tokugawa regime, which came to an end in 1867 after continuing for about two and a half cen turies, are Shibayama Senzo, who is known to have devised a method of inlay in the An-ei era (1772-81), using corals, ivory, horns, etc. ; Garan of Osaka, who was fond of carving birds, animals and insects for netsuke at about the same time; Izumiya Tomotada of Kyoto, who is known to have excelled in the Tem mei era (1781-89) in netsuke of cows and oxen in realistic carv ing; Tametada of Owari, an expert relief carver; Tomotane of Kyoto, whose favourite subjects for netsuke were warriors, angels, insects and animals; Hoshin of Kyoto, skilled in carving palaces and landscapes in half-opened shells and miniature figures in buildings; Masanao of Kyoto, who generally drew his sub jects from hermits, animals, birds and insects, especially frogs in the act of jumping; Masatoshi, also of the Temmei era, who was an expert netsuke carver, being fond of figures, demons and masks for his subjects; Nakayama Yamatome of Yedo, skilled in minute carving, such as 53 stages of the Tokaido road, or portraits of 36 famous poets, on a single small piece; Noriaki, who was well-known in the Kwansei era (1789-1801) for figures and animal subjects; Miyasaka Hakuryu of Kyoto, who excelled in carving tigers, monkeys and dragons ; Genryosai Minkoku, whose favourite subjects were grotesque hermits, animals and fishes ; Ranko of Izumo, who left good works in a variety of subjects, such as figures, animals, birds, flowers and attempted landscapes on netsuke; and such others as Masaharu, Rantei, Yoshimasa, Yoshinaga, Shokyusai, Mitsushige, Tadachika, Ik kosai Toun, Rakuwosai, Masakazu, Shinshisai, Tomochika, Gyo kuyosai, and his pupil Ozaki Kokusai, some of whom have left masterpieces in ivory netsuke and other carvings.

Scope.—Immediately after the Restoration of 1868, ivory ob jects found their way abroad, having attracted the attention of foreign collectors. So great was the foreign demand for the ivory carvings that they became quite an item in the Japanese export for some time. It was a great encouragement to the carvers, as their native patrons were becoming scarce, and the call for netsuke in Japan came to an end when the cigarette drove away tobacco pouches. However, the demand was for a greater and cheaper production, rather than for a high quality of work, and the standard of the craft deteriorated in consequence. Neverthe less, there were a number of masters who did produce works of high merit. Among them Asahi Gyokuzan and Ishikawa Mitsuaki stand pre-eminent. The former made his reputation in wonder fully minute and realistic carving of skulls in ivory and in intri cate and beautiful inlaid works, while the latter produced excel lent figure ornaments as well as exquisite low relief in ivory. Among other well-known ivory carvers of more recent times mention may be made of Shimamura Toshiaki, Asahi Meido, Soma Senrei, Kaneda Kenjiro, Nishino KOgyoku, Otani Mit sutoshi and Ono HOfii, whose works have been much admired.

Designs in ivory netsuke are manifold, embracing almost every imaginary subject. However, the striking feature was the rounded corners, avoiding sharp edges, so as not to scratch the inro, which is generally in lacquer of costly decoration. Influences of con temporary artists like Hokusai and of such comic styles of painting as Otsu-ye are shown in the choice and treatment of the subject. Taoists and, later, genre figures commonly supplied the motives, and various animals, especially those in the 12 signs of the zodiac, were treated in all moods and attitudes.

Uses.—Apart from the netsuke and ornaments for the alcove, ivory has been used extensively as an ornamental piece for the kakemono, the mounted hanging paintings that can be rolled up when not in use. For plectra for shamisen (popular three stringed musical instruments) ivory has been invaluable. More over it has long occupied a dignified position as an important accessory to the cha-no-yu (ceremonial tea) utensils. The lid of the tea caddy (cha-ire) is almost exclusively made of ivory, the bottom being lined with gold foil. It is generally in a simple but graceful form, having a knob in the centre with concentric cir cular lines or relief as ornaments. However, the portion of the tusk with black stains or flaws is often chosen for making a lid, care being taken to let such a flaw appear as an ornament or "scenery," as it is called, which often constitutes a striking fea ture in the ware. Tea scoops also are sometimes made of ivory, though most commonly they are made of bamboo by bending the flattened end of it to scoop out pulverized tea leaves from the caddy in preparing the tea.

It is for kakemono, shamisen plectra, tea caddy lids and tea scoops, though these are not of very great artistic value, that ivory is chiefly used in Japan at the present time, since netsuke are almost entirely out of fashion. One still sees in shop windows ivory carvings of wide variety, and there are some skilled carvers in ivory producing works of unquestionable merit, but it cannot be denied that most of them cater for the taste of Europeans and Americans, and that the true refined taste of the Japanese rarely admits an ivory carving to the tokonoma.

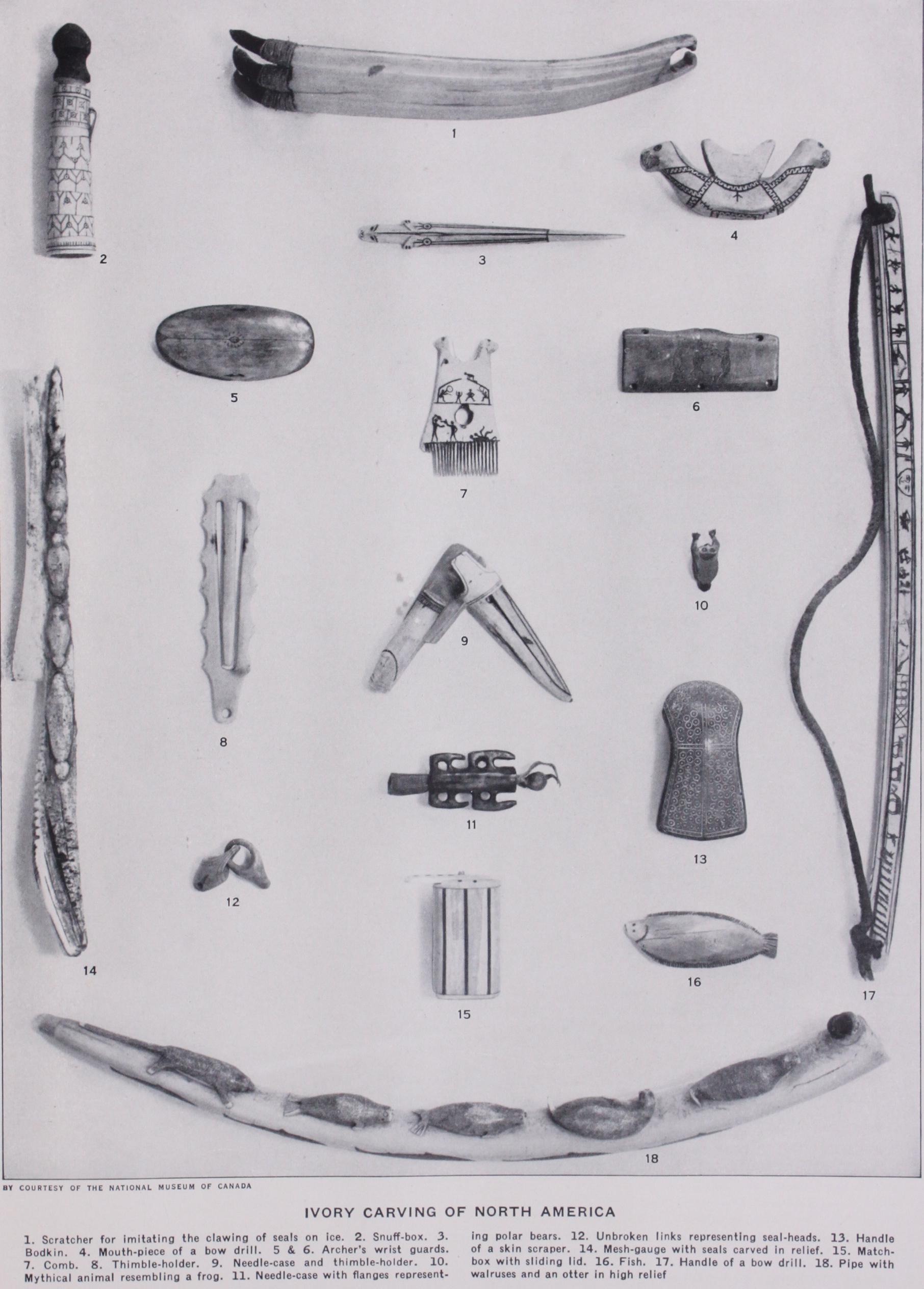

See A. Brockhaus, Netsuke-Versuch einer Geschichte der Japanischen Schnitzkunst (Leipzig, 1905). (J. HAR.) To the primitive North American Indian unacquainted with metals except the soft copper found in a pure state in certain isolated places, the gleaming ivory teeth of the animals he hunted always possessed a special attraction. The tooth of the beaver made him an efficient knife or graving tool, the tooth of the bear an admirable fish-lure. Often he attached rows of teeth to his clothing, partly to show his success in hunting, partly also because he found pleasure in their sheen. But there are three animals, the walrus, the narwhal and the elephant, gifted by nature with a larger share of ivory than the rest, and it so happened that in North America two of these animals were available only in the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions where the timber that supplies so many of man's needs was either scarce or lacking. The third animal, the elephant, was extinct in every part of America, but its tusks were easily accessible in certain parts of Alaska, al though rare and usually deeply buried elsewhere. Consequently it was among the Eskimo tribes inhabiting the Arctic and sub Arctic regions that the art of carving ivory for both utilitarian and aesthetic purposes attained its highest development.

The ivory in commonest use is walrus ivory, which is densest in structure and easiest to secure. Narwhal tusks are twisted and hollow, which renders them unsuited for engraving or carving, although they served the old Eskimos of Hudson bay for harpoon shafts and other implements. Mammoth ivory is almost as dense as walrus ivory, and hollow only towards the base. Fossilization, i.e., darkening through long contact with minerals in the soil, gives a variety of soft, deep colours greatly appreciated by curio collectors ; hence traders often immerse white ivory in boiling coffee and other liquids to give its surface a spurious fossilization.

Our earliest specimens of Eskimo carving seem to come from the Bering sea region. They are not numerous, and are scat tered through several museums, their antiquity unrecognized because they were purchased from ignorant Eskimos and not excavated by trained archaeologists. We may distinguish them by two criteria, deepness of colour (a very unsafe guide) and the style of ornamentation ; sometimes we may add a third, the shapes of the specimens, which often differ from the later Eskimo types. There is carving in the round, apparently,—heads of seals and other realistic figures very similar and perhaps not inferior to anything we find in more recent Eskimo remains ; but still more abundant are finely etched geometric patterns covering sur faces even of utilitarian objects such as snow-goggles and harpoon foreshafts that in later periods seldom carried any ornamenta tion. The artists of this ancient school, unlike their successors, disliked straight lines, preferring the graceful curves, scrolls and concentric circles that are so characteristic of Maori and Mel anesian art. Unlike the Melanesians, however, they did not allow their ornamentation to run riot, but subordinated it in conform ity with the shape and purpose of the object so as to produce a natural balance. The freehand drawing on the more carefully worked specimens is admirable; many of the concentric circles with incised dots are so accurate that they seem hardly traceable without compasses (fig. I).

The period at which this remarkable art flourished is as ob scure as its origin. It surely dates back at least i,000 years, but how much more than this we cannot guess.

The curtain then closes for a period on the early history of the Arctic. When it opens again, some ten centuries ago, we find the Eskimos occupying the whole coast line from Bering sea to Labrador and Greenland. Ivory-carving flourished in both the west and the east, but the finest specimens come from the west.

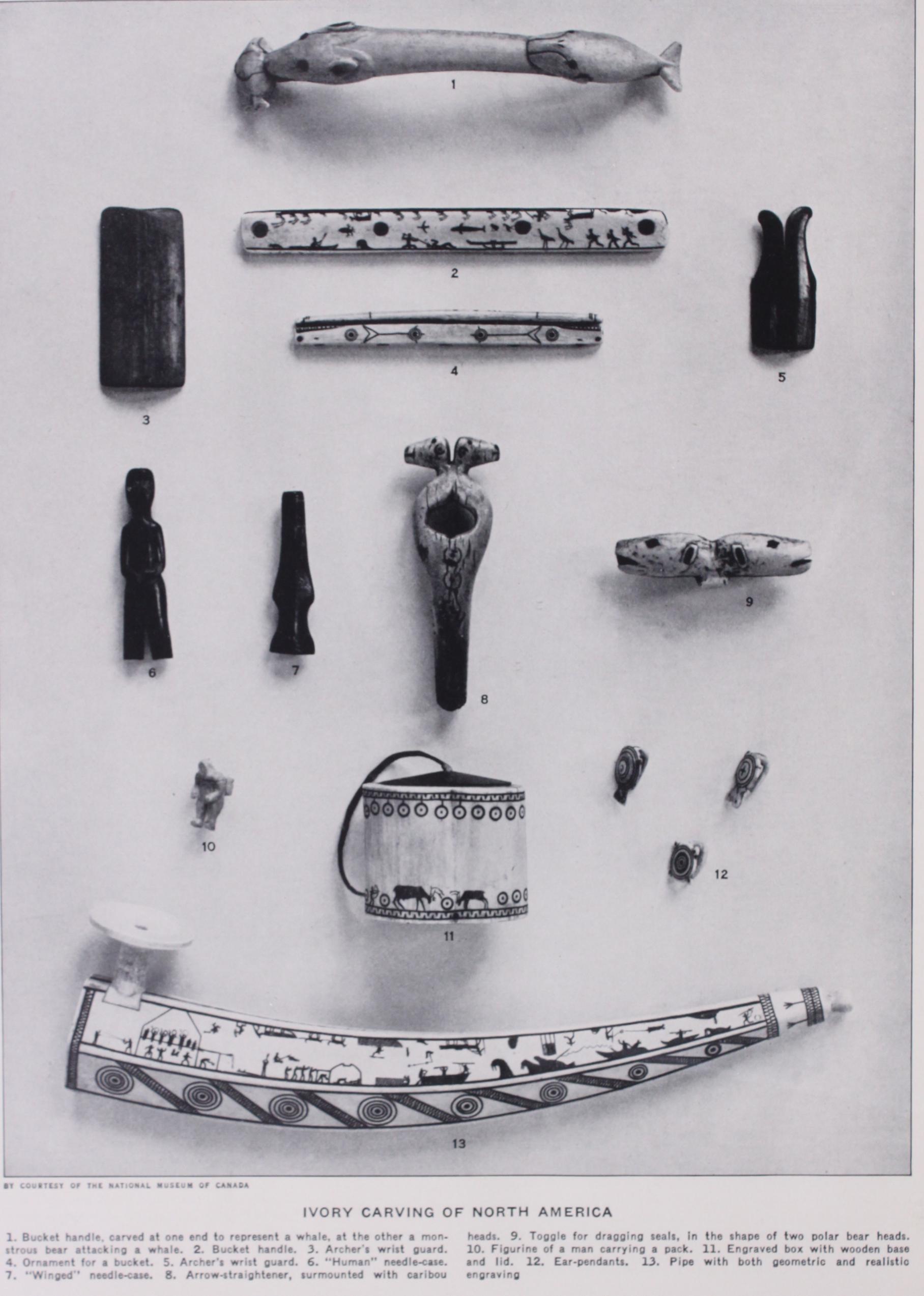

Even the most everyday objects, such as needle-cases, toggles for the dog-harness and harpoon-heads, underwent ornamenta tion or were given a decorative form. There are ornaments made of two unbroken links each carrying a representation of an animal's head, sometimes slightly conventionalized but often quite real istic. The needle-case with thimble-holder attached that is shown in Pl. IX., fig. 9 dates from post-European times, but it also has been carved from one unbroken section of a walrus tusk.

The Eskimo needle-case is a hollow cylinder of bone or ivory that contains a sealskin thong carrying the bone or copper needles. The ivory carvers of an cient days could not remain content with a plain undecorated tube, but for some reason not as yet understood, expanded it into what has been called the "winged" form (P1. X., fig. 7), which they engraved with their characteristic geometric designs. Winged needle-cases have been found in old ruins from Alaska to the Labrador peninsula, so that the type was established at least i,000 years ago. In Alaska the artists let their fancy play with the dif ferent elements of this conventional form. Sometimes they developed the ends of the needle-case, sometimes the flanges or wings and the hardly perceptible knobs below them. Since all their sculpture (as opposed to their engraving) tended towards real ism, these elements became elaborated into animal forms, as in Pl. IX., fig. I I. Attached to the sealskin thong that passed through the tube there was always a toggle of some kind to assist in draw ing the needles in and out, and it may be that the round, button like toggle, fitting on top of a "winged" needle-case, suggested the human figure. At all events, we have actually secured from quite early sites many needle-cases in human form,—always female, for though men were the ivory carvers, the women performed all the sewing. In some specimens the head is hollow, as in P1. X., fig. 6; in others it is solid and separate from the trunk, serving as the button for the sealskin thong.

Animal heads, usually carved on tools connected with the chase, are nevertheless much commoner than human figures in these old remains. The implement in the form of two polar bear heads joined together (Pl. X., fig. 9) is a toggle for dragging home seals. The ears of the bears show admirable workmanship, and the eyes are skilfully represented by plugs of dark-coloured antler. Possibly the holes marking the nostrils were originally plugged in the same way. The heads would be almost identical if the artist had not fancifully depicted one bear with teeth and one without. This specimen is particularly interesting because of the wide deep groove on the underside, which still reveals the stone age method of its formation. The workman first drilled a series of holes, side by side, then broke away the intervening walls.

From a somewhat later period, the early iron age, comes the arrow-straightener shown in P1. X., fig. 8, which is surmounted with the heads of what appear to be caribou. Here again the artist has used plugs of dark ivory to represent the eyes and nostrils, but for the somewhat misplaced ears he contented himself with a conventional design, an engraved dot and circle. This pattern, so widely spread over the globe, appears fairly frequently in Alaska, even from the earliest times. (See P1. X., fig. II, an ivory box with wooden base and lid; Pl. IX., fig. 2, a snuff box and Pl. IX., fig. 13, handle of a skin-scraper, all from vicinity of Norton sound.) The Russian explorations of the Chukchee peninsula in the middle and latter half of the 17th century caused a steady stream of iron to flow across Bering strait. The possession of iron tools immediately brought about a striking development in ivory work, particularly in Alaska. Older implements and ornaments appeared in new forms, as the skin-scraper of Pl. JX., fig. 13, the thimble holder of P1. IX., fig. 7, the mouthpiece of the bow drill in Pl. IX., fig. 4 and the delicate little ear pendants with their concentric circles and holes for suspending glass beads (Pl. X., fig. 12). With more efficient tools the artist could give freer rein to his imagination, and for the first time, apparently, we find carvings in the round, or in high relief, arranged to compose a scene. To this post-iron period belongs the Alaskan bucket handle of P1. X., fig. 1, where a polar bear is seizing a fish. The Labrador penin sula has produced some remarkable carved ivory tusks in the past, probably recent, that illustrate the same artistic growth.

Far more striking, however, than either of these developments was the sudden emergence of realistic engravings in Alaska, and the birth, nearly full-grown, of a picture-writing, that has often been compared by writers too apt to forget its modernity with the scenes painted by palaeolithic man on the walls of French and Spanish caves, and the drawings made on rocks by the Bushmen in South Africa. Actually very little realistic engraving seems to occur before the Eskimos had direct or indirect contact with Europeans, and for some time after this contact realistic designs contested the field with the older geometric patterns without gain ing the supremacy (compare the designs on the two archer's wrist guards in Pl. X., figs. 3 & 5). In museum collections the oldest pipes (which were first introduced from Siberia about the same time as iron) seem to be carved in relief, and engraved either with geometric designs or with realistic figures of animals arranged without any relation to each other except a purely spatial one (Pl. IX., fig. 18). It was not until the 19th century indeed that picture-writing became firmly established and succeeded in rele gating the older geometric engraving to the background ; and even then it failed to gain a foothold in the Eskimo area except Alaska.

From about 175o onward picture-writing in Alaska over shadowed the older engraving of geometric patterns, but by no means superseded it. Nor did it seriously affect the carving of detached figures, or of figures in high or low relief. A few specimens from the last 15o years may be illustrated to compare with the earlier art forms. P1. IX., fig. 1 shows a graceful tool that was used by hunters to simulate the scratching of seals on the ice; it dates from about the beginning of European contact, although the claws have been relashed with sinew in modern times. P1. IX., fig. 14, from the early 19th century perhaps, is a gauge for regu lating the mesh of the sealing net ; besides the seals carved on its upper surface there is some crude picture-writing on the under side. Pl. IX., figs. 3 & 16; Pl. X., fig. 4 are productions from the second half of the 19th century; Pl. IX., fig. 3 a needle for lacing skins together; Pl. X., fig. 4 an ornament, probably for a bucket; Pl. IX., fig. 16, a fish.

It is too early yet to foresee what will result from the com mercialization of Eskimo ivory-carving during the last so years. Already it has produced in Alaska professional carvers who earn their livelihood by supplying the demands of the curio trade. Undoubtedly these modern artists possess as much skill as their ancestors (see P1 X., fig. 1o, from Hudson bay, a cleverly bal anced statuette of a man carrying a pack, and P1. IX., fig. 1o, from Alaska, which represents a mythical monster) ; but they have failed to apply their skill to the production of objects that are acceptable to the civilized world at large. (See also SCULP TURE; SCULPTURE TECHNIQUE; NORTH AMERICA: Ethnology.) (D. J.)