Ivory Carving

IVORY CARVING. The use of ivory as a material pecu liarly adapted for sculpture and decoration has been universal in the history of civilization. In order to treat the subject adequately and give the relative importance of the art in different countries, the following division is made : History, covering various periods and countries, (2) Chinese, (3) Japanese, (4) North American. For ivory carving technique see SCULPTURE : Tech nique.

It is probable that ivory carving has a long and continuous his tory, extending from the Palaeolithic period to the present day, but even so there are gaps and it is rather a question of a succession of groups than of an unbroken historical development. The ques tion of the supply of the raw material perhaps partially accounts for the apparently barren periods, though it must also be remem bered that we can only judge by the existing work and it may only be chance which has preserved these particular examples and not others. But there are historical grounds for these long periods of inactivity. In Europe the ivory carver was dependent on more or less remote countries for his material and it is easy to see that in the 7th and 8th centuries the Mohammedan conquests must have interfered to some extent with the traffic between Nubia (one of the great distributing centres) and Egypt, and so through Syria and Cyprus with Europe. By what route the vast quantities of tusks necessary to furnish the raw material for the huge output of the Carolingian and Gothic periods arrived in Europe it is difficult to say. Communication with the East was probably furni3hed by the navies of Cyprus but there appears to be no record of the port at which the ivories were landed. In western and northern Europe, chiefly during the Romanesque period, walrus tooth (or morse ivory) was largely used in place of elephant tusk, probably owing to the fact that it was more easily obtainable ; more rarely whale's bone was employed. Ordinary bone was also used, notably in the Coptic period and again later, at the end of the 14th cen tury, in northern Italy. Ivory uncoloured, as we generally see it now, does not seem to have appealed to the ancient or mediaeval imagination and the carvings were in most cases originally lavishly coloured and gilded and frequently enriched with jewels and pastes. At certain times, notably in the Carolingian period in Western Europe and in the Byzantine empire, ivory-carving reached an importance not perhaps warranted by its intrinsic merits. The very considerable influence exercised on Romanesque sculpture by Byzantine art was probably largely derived through carved ivories. Illuminated manuscripts were in their turn a fer tile source of inspiration for carved ivories especially of the Byzantine and Carolingian periods. Textiles, too, furnish numer ous prototypes for the Coptic bone-carvings and for the beasts and mythological monsters found on Byzantine and Mohammedan carvings. The connection between carved ivories and metalwork is frequently very close, as in the case of silver caskets of the Byzantine period at Anagni and Cracow.

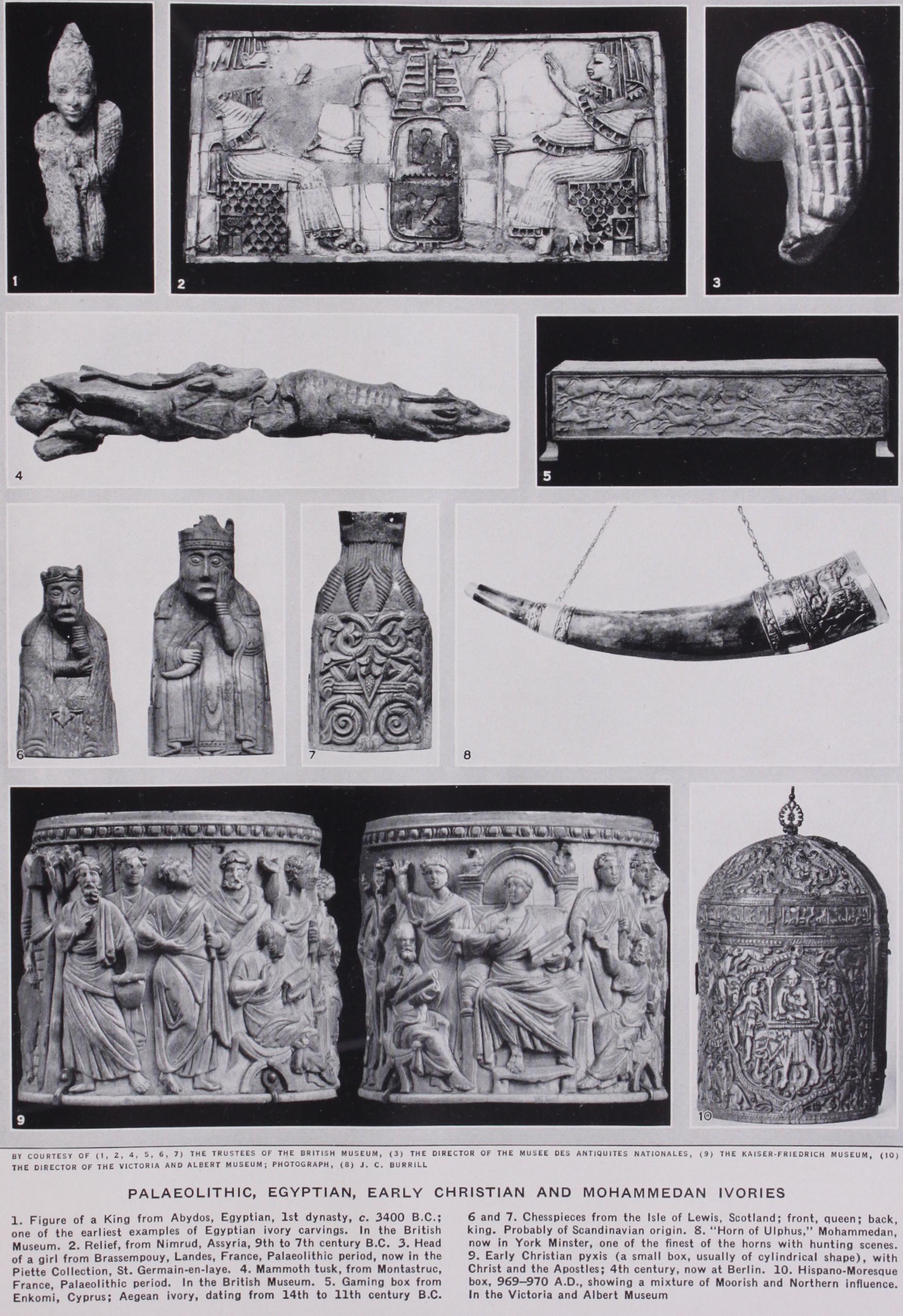

After the I 2th century with the widespread development of monumental sculpture ivory-carving ceases to have the same his torical significance, though charming and extremely accomplished work was produced both during the Gothic and subsequent Carvings of the Palaeolithic Period.—Carvings in ivory, bone and horn are so numerous in certain periods of the stone age that one of these, the Aurignacian, has been called the ivory period. Most of the carvings have been found in southern France, in the Dordogne and Arriege districts, though a few come from the Riviera and Germany. The earlier examples usually take the form of nude female figures, the aesthetic worth of which is usually almost negligible, but a small head of a girl found at Bras sempouy (Landes) has real artistic value. The animal carvings belong almost entirely to the succeeding Magdalenian period; these are frequently of extraordinary merit. The material is usually reindeer horn or more rarely mammoth ivory; among the objects in the latter is a tusk in two parts carved in the round with reindeer, found at Montastruc, Bruniquel (now in the Brit ish Museum). In reindeer horn is a magnificent dagger handle from Laugerie Basse (now in the museum at St. Germain) with a figure of a kneeling reindeer, a fine example of the utilization of the natural form of the material. Though no hard and fast de marcation can be made, engraving is probably rather posterior to carving in the round. The engravings usually represent animals, often rendered in a masterly manner and combined to form scenes, but occasionally human figures are represented in a rudimentary and animal-like form.

Egyptian Ivories.

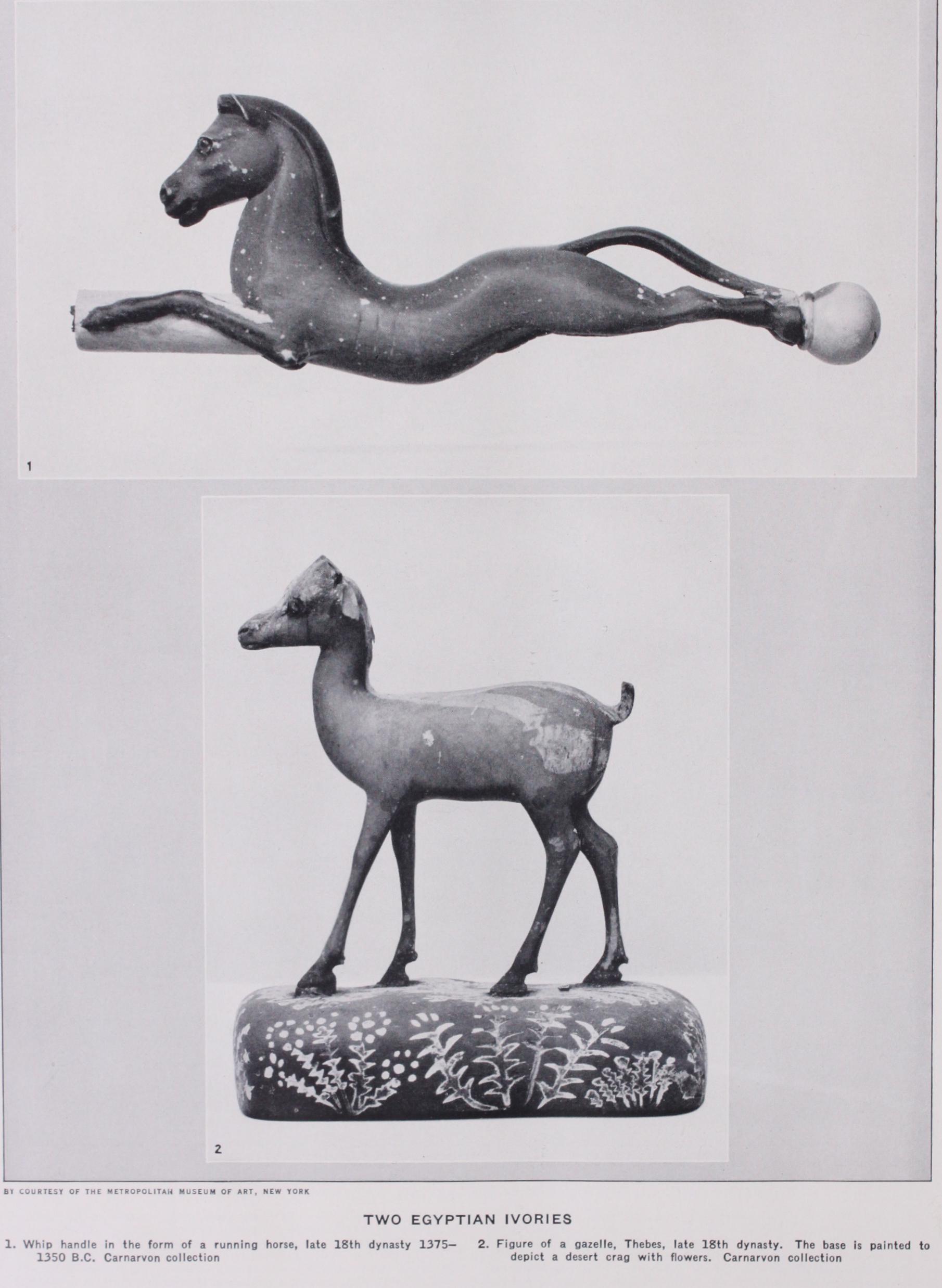

Ivory and bone were worked from a very early period in Egypt, the supply of the raw material being easily obtained from Ethiopia and possibly Asia Minor. A large num ber of combs, hairpins and other utensils dating from the Pre dynastic and Early Dynastic period have been found at Nagada and other sites, and a very fine handle carved with hunting and other scenes found at Gebel-el-arak is now in the Louvre. To the same period belong some at any rate of an extensive series of nude female figures, probably of amuletic significance, carved in varying degrees of crudity. A considerable number of ivory figures of men and women, some in embroidered robes, were found by Mr. Quibell at Hierakonpolis, many of which show consider able aesthetic feeling, but among the masterpieces of early Egyp tian carving are two statuettes, both found at Abydos : one, a king belonging to the First Dy nasty (now in the British Mu seum) wearing the crown of Upper Egypt and a richly em broidered robe; the second, now at Cairo, representing the King Khufu (Fourth Dynasty), the builder of the Great Pyramid.The later work, though frequently of very fine quality, is usually more purely decorative in in tention, being largely used for handles, spoons, inlays for caskets and furniture. (See also EGYPT : Ancient Art and Archae ology.) Babylonian and Assyrian Ivories.—Though only a few examples have been found up to the present there is every reason to believe that ivory was carved in Babylonia from a period at least as early as in Egypt. The later work of about the 9th to the 7th centuries B.C. is, how ever, represented in the British Museum by an unrivalled series of ivories from Nimrud many of which show strong Egyptian influence; these were frequently inlaid with gold and lapis-lazuli, a method of decoration which is found elsewhere as for example at Mycenae and throughout the Aegean. Apparently contemporary with these are a series of fragments, chiefly heads, more purely indigenous in type. Both groups show an admixture of other influence and it has been plausibly suggested that the carvers were Phoenicians.

Aegean, Etruscan, Greek and Roman Ivories.

Among the earliest Aegean carvings that have any considerable aesthetic value are the small ivory figures of acrobats found in Crete at Knossos, now in the museum at Candia. These must be rated beside the masterpieces of Minoan art and may be dated about the 16th century B.C. The celebrated figure of the snake goddess, now at Boston, has also been ascribed to the same period. A considerable number of ivories of very fine workmanship, now in the British Museum, which may be assigned to a date between the 14th and the 11th centuries have been found at Enkomi, in the island of Cyprus. They include a gaming box carved on the sides in low relief with hunting scenes, and two mirror handles with combats between human beings and monsters. Ivories similar in style and of about the same period have been found in Greece at Sparta and Mycenae (both groups being now in the museum at Athens). It has been suggested that one of the centres of production was perhaps Cyprus, but it is much more probable that they were made in Syria or possibly on the south coast of Asia Minor. In any case the main influence is Asiatic in deriva tion.

To a period between the 9th and the 6th centuries B.C. belong extensive groups of carvings which seem to derive from the same cultural source as the earlier ivories. These groups, which show close analogies of style both among themselves and with the Nimrud carvings, have been found on various sites—at Ephesus, Rhodes, Sparta and in Italy and Spain. The dominating style is Asiatic but in some cases there are traces of Egyptian influence. The ivories from Sparta, now in the Museum at Athens, were excavated in the sanctuary of Artemis Orthia and date mainly from the 8th and 7th centuries; they show traces of Ionic influ ence and were possibly worked locally. Among them are fibula plaques carved in relief, figures of animals carved in the round, statuettes and a fine relief with a warship, this last inlaid with amber.

The carvings from Ephesus, now in the museum at Constan tinople, were found in the temple of Artemis and date from about the same period. They consist chiefly of statuettes, the costume of which shows Asiatic (perhaps Hittite) influence, and some finely conceived animal figures.

The earliest ivories found in Etruscan tombs in Italy belong to about the same period and present many difficulties as to origin. Some of the finest examples were found in the Barberini Tomb at Praeneste south of Rome ; these included a tazza on a high foot, and three arms and hands the use of which is not clear; all are decorated with bands of centaurs, griffins and animals in pro cession. It has been suggested, with considerable likelihood, that these are importations from Cyprus, probably of Phoenician workmanship, but even if they are native Etruscan imitations the motives are derived from an oriental source. Slightly later in date is a box found at Chiusi in northern Etruria, now in the Museo Archeologico at Florence.

It is remarkable that no ivories of importance belonging to the earlier classical period of Greek art have survived, though we know from documentary evidence that they existed. To the Graeco-Roman period should probably be assigned a very beauti ful head found in the Roman theatre at Vienne (Isere) now in the Musee Archeologique of that town. A fine head of a goddess, together with fragments of arms in the Vatican, probably belongs to the same period, but it may serve to give an idea of the chryselephantine statuary of Greece known to us only from the descriptions of classical writers. A number of smaller ivories of the Roman period have survived, among them being a small figure of a tragic actor (in the Dutuit collection in Paris) and a statuette of a hunchback (in the British Museum), but they are mostly objects for domestic use.