Ivory

IVORY, strictly speaking a term confined to the material represented by the tusk of the elephant, and for commercial purposes almost entirely to that of the male elephant. In Africa both the male and female elephant produce good-sized tusks; in the Indian variety the female is much less bountifully pro vided, and in Ceylon perhaps not more than 1% of either sex have any tusks at all. Ivory is in substance very dense, the pores close and compact and filled with a gelatinous solution which contributes to the beautiful polish which may be given to it and makes it easy to work. It may be placed between bone and horn., more fibrous than bone and therefore less easily torn or splin tered. For a scientific definition it would be difficult to find a better one than that given by Sir Richard Owen. He says : "The name ivory is now restricted to that modification of dentine or tooth substance which in transverse sections or fractures shows lines of different colours, or striae, proceeding in the arc of a circle and forming by their decussations minute curvilinear lozenge shaped spaces." These spaces are formed by an immense number of exceedingly minute tubes placed very close together, radiating outwards in all directions. It is to this arrangement of structure that ivory owes its fine grain and almost perfect elasticity, and the peculiar marking resembling the engine-turning on the case of a watch, by which many people are guided in distinguishing it from celluloid or other imitations. Elephants' tusks are the upper incisor teeth of the animal, which, starting in earliest youth from a semi-solid vascular pulp, grow during the whole of its existence, gathering phosphates and other earthy matters and becoming hardened as in the formation of teeth generally. The tusk is built up in layers, the inside layer being the last pro duced. A large proportion is embedded in the bone sockets of the skull, and is hollow for some distance up in a conical form, the hollow becoming less and less as it is prolonged into a narrow channel which runs along as a thread or as it is sometimes called, nerve, towards the point of the tooth. The outer layer, or bark, is enamel of similar density to the central part. Besides the elephant's tooth or tusk we recognize as ivory, for commercial purposes, the teeth of the hippopotamus, walrus, narwhal, cacha lot or sperm-whale and of some animals of the wild boar class, such as the wart-hog of South Africa. Practically, however, amongst these the hippo and walrus tusks are the only ones of importance for large work, though boars' tusks come to the sale-rooms in considerable quantities from India and Africa.

Sources of Ivory.—Generally speaking, the supply of ivory imported into Europe comes from Africa; some is Asiatic, but much that is shipped from India is really African, coming by way of Zanzibar and Mozambique to Bombay. A certain amount is furnished by the vast stores of remains of prehistoric animals still existing throughout Russia, principally in Siberia in the neighbourhood of the Lena and other rivers discharging into the Arctic ocean. The mammoth and mastodon seem at one time to have been common over the whole surface of the globe. In England tusks have been dug up—for instance at Dungeness— as long as I2ft. and weighing 200 lb. The Siberian deposits have been worked now for nearly two centuries. The store appears to be as inexhaustible as a coalfield. Some think that a day may come when the spread of civilization may cause the utter dis appearance of the elephant in Africa, and that it will be to these deposits that we may have to turn as the only source of animal ivory. Of late years in England the use of mammoth ivory has shown signs of decline. Little or none passed through the London sale-rooms after 190o. Before that, parcels of io to 20 tons were not uncommon. Not all of it is good; perhaps about half of what comes to England is so, the rest rotten ; specimens, however, are found as perfect and in as fine condition as if recently killed, instead of having lain hidden and preserved for thousands of years in the icy ground. There is a considerable literature (see SHOOTING) on the subject of big-game hunting which includes that of the elephant, hippopotamus and smaller tusk-bearing animals. Elephants until comparatively recent times roamed over the whole of Africa from the northern deserts to the Cape of Good Hope. They are still abundant in Central Africa and Uganda, but civilization has gradually driven them farther and farther into the wilds and impenetrable forests of the interior.

The quality of ivory varies according to the districts whence it is obtained, the soft variety of the eastern parts of the conti nent being the most esteemed. When in perfect condition African ivory should be, if recently cut, of a warm, transparent, mellow tint, with as little as possible appearance of grain or mottling. Asiatic ivory is of a denser white, more open in texture and softer to work. But it is apt to turn yellow sooner, and is not so easy to polish. Unlike bone, ivory requires no preparation, but is fit for immediate working. That from the neighbourhood of Cameroon is very good, then ranks the ivory from Loango, Congo, Gabun and Ambriz; next the Gold Coast, Sierra Leone and Cape Coast Castle. That of French Sudan is nearly always "ringy," and some of the Ambriz variety also. We may call Zanzibar and Mozambique varieties soft ; Angola and Ambriz all hard. Ambriz ivory was at one time much esteemed, but there is comparatively little now. Siam ivory is rarely if ever soft. Abyssinian has its soft side, but Egypt is practically the only place where both descriptions are largely distributed. A draw back to Abyssinian ivory is a prevalence of a rather thick bark. Egyptian is liable to be cracked, from the extreme variations of temperature; more so formerly than now, since better methods of packing and transit are used. Ivory is extremely sensitive to sudden extremes of temperature ; for this reason billiard balls should be kept where the temperature is fairly equable.

The market terms by which descriptions of ivory are distin guished are liable to mislead. As is often the case they most generally refer to ports of shipment rather than to places of origin. For instance, "Malta" Ivory is a well-understood term, yet there are no ivory-producing animals in that island.

Tusks should be regular and tapering in shape, not very curved or twisted, for economy in cutting; the coat fine, thin, clear and transparent. The substance of ivory is so elastic and flexible that excellent riding-whips have been cut longitudinally from whole tusks. The size to which tusks grow and are brought to market depends on race rather than on size of elephants. The latter run largest in equatorial Africa. Asiatic bull elephant tusks seldom exceed so lb. in weight, though lengths of 9f t. and up to 15o lb. in weight are not entirely unknown. Record lengths for African tusks are the one presented to George V., when prince of Wales, on his marriage (1893), measuring 8ft. 7 in. and weighing 165 lb., and the pair of tusks which were brought to the Zanzibar market by natives in 1898, weighing together over 450 lb. One of the latter is now in the Natural History Museum at South Kensington; the other is in Messrs. Rodgers & Co.'s collection at Sheffield. For length the longest known are those belonging to Messrs. Rowland Ward, Piccadilly, which measure 1ft. and 1ift. 5in. respectively, with a combined weight of 293 lb. Osteodentine, resulting from the effects of injuries from spearheads or bullets, is sometimes found in tusks. This forma tion, resembling stalactites, grows with the tusk, the bullets or iron remaining embedded without trace of their entry.

Hard and Soft Ivory.—The most important commercial distinction of the qualities of ivory is that of the hard and soft varieties. The terms are difficult to define exactly. Generally speaking, hard or bright ivory is distinctly harder to cut with the saw or other tools. It is, as it were, glassy and transparent. Soft contains more moisture, stands differences of climate and tem perature better and does not crack so easily. The expert is guided by the shape of the tooth, by the colour and quality of the bark or skin, and by the transparency when cut, or even before, as at the point of the tooth. Roughly, a line might be drawn almost centrally down the map of Africa, on the west of which the hard quality prevails, on the east the soft. In choosing ivory—for example for knife-handles—people rather like to see a pretty grain, strongly marked ; but the finest quality in the hard variety, which is generally used for them, is the closest and freest from grain. The curved or canine teeth of the hippopotamus are valuable and come in considerable quantities to the European markets. Owen describes this variety as "an extremely dense, compact kind of dentine, partially defended on the outside by a thin layer of enamel as hard as porcelain; so hard as to strike fire with steel." By reason of this hardness it is not at all liked by the turner and ivory workers, and before being touched by them the enamel has to be removed by acid, or sometimes by heating and sudden cooling when it can be scaled off. The texture is slightly curdled, mottled or damasked. Hippo ivory was at one time largely used for artificial teeth, but now mostly for umbrella and stick handles; whole (in their natural form) for fancy door-handles and the like. In the trade the term is not "riverhorse" but "seahorse" teeth. Walrus ivory is less dense and coarser than hippo, but of fine quality—what there is of it—for the oval centre which has more the character of coarse bone unfortunately extends a long way up. At one time a large supply came to the market, but of late years there has been an increasing scarcity, the animals having been almost exterminated by the ruthless persecution to which they have been subjected in their principal haunts in the northern seas. It is little esteemed now, though our ancestors thought highly of it. Comparatively large slabs are to be found in mediaeval sculpture of the 11th and 12th centuries, and the grips of most oriental swords, ancient and modern, are made from it. The ivory from the single tusk or horn of the narwhal is not of much commercial value except ' as an ornament or curiosity. Some horns attain a length of 8 to soft., 4in. thick at the base. It is dense in substance and of a fair colour, but owing to the central cavity there is little of it fit for anything larger than napkin-rings.

Ivory in Commerce.

Almost the whole of the importation of ivory to Europe was until recent years confined to London, the principal distributing mart of the world. But the opening up of the Congo trade placed the port of Antwerp in a position which has equalled that of London. Other important markets are Liverpool and Hamburg; and Germany, France and Portugal have colonial possessions in Africa, from which it is imported. America is a considerable importer for its own requirements. Every pair of tusks that comes to the market represents a dead elephant, but not necessarily by any means a slain or even a re cently killed one, as is popularly supposed. By far the greater proportion is the result of stores accumulated by natives, a good part coming from animals which have died a natural death. Not 2o% is live ivory or recently killed; the remainder is known in the trade as dead ivory.

The British supplies of ivory have greatly fallen since the '9os. In 1827 the London market received 3,000 cwt. ; in 185o, 8,000 cwt. In 1890 British imports increased to 14,349 cwt., but since then there has been decline to 10,911 cwt. in 1895; 9,889 cwt. in i9oo; 5,095 cwt. in 1927. The price has greatly risen in consequence, the British imports of all grades of ivory in 1927 averaging as much as £66 per cwt. ; while £154 was paid for East India billiard ball pieces. If we allow say 30 lb. per pair of tusks, each cwt. imported represents nearly four elephants, and we must expect supplies further to decline.

The leading London sales are held quarterly in Mincing lane, a very interesting and wonderful display of tusks and ivory of all kinds being laid out previously for inspection in the great warehouses known as the "Ivory Floor" in the London docks. The quarterly Liverpool sales follow the London ones, with a short interval.

Industrial Applications.—The important part which ivory plays in the industrial arts not only for decorative, but also for domestic applications is hardly sufficiently recognized. Nothing is wasted of this valuable product. Hundreds of sacks full of cuttings and shavings, and scraps returned by manufacturers after they have used what they require for their particular trade, come to the mart. The dust is used for polishing, and in the preparation of India ink, and even for food in the form of ivory jelly. The scraps come in for inlaying and for the number less purposes in which ivory is used for small domestic and deco rative objects. India, which has been called the backbone of the trade, takes enormous quantities of the rings left in the turning of billiard-balls, which serve as women's bangles, or for making small toys and models, and in other characteristic Indian work. Without endeavouring to enumerate all the applications, a glance may be cast at the most important of those which consume the largest quantity. Chief among these is the manufacture of billiard-balls, of cutlery handles, of piano-keys and of brushware and toilet articles. Billiard-balls demand the highest quality of ivory ; for the best balls the soft description is employed, though recently, through the competition of bonzoline and similar substi tutes, the hard has been more used in order that the weight may be assimilated to that of the artificial kind. Therefore the most valuable tusks of all are those adapted for the billiard-ball trade. The term used is "scrivelloes," and is applied to teeth proper for the purpose, weighing not over about 7 lb. The division of the tusk into smaller pieces for subsequent manufacture, in order to avoid waste, is a matter of importance.

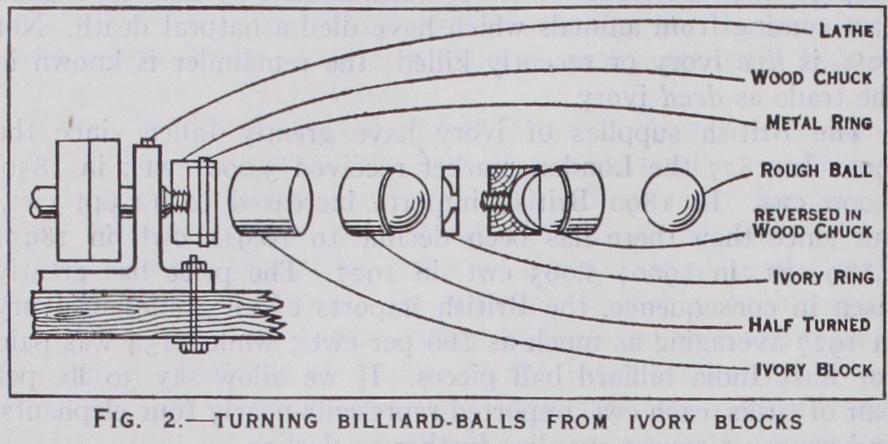

The accompanying diagrams (figs. i and 2) show the method; the cuts are made radiating from an imaginary centre of the curve of the tusk. In after processes the various trades have their own particular methods for making the most of the material. In making a billiard-ball of the English size the first thing to be done is to rough out, from the cylindrical section, a sphere about 21,in. in diameter, which will eventually be or sometimes for professional players a little larger. One hemisphere—as shown in the diagrams (fig. 2)—is first turned, and the resulting ring detached with a parting tool. The diameter is accurately taken and the subsequent removals taken off in other directions. The ball is then fixed in a wooden chuck, the half cylinder reversed, and the operation repeated for the other hemisphere. It is now left five years to season and then turned dead true. The rounder and straighter the tusk selected for ball-making the better. Evi dently, if the tusk is oval and the ball the size of the least di ameter, its sides which come nearer to the bark or rind will be coarser and of a different density from those portions further removed from this outer skin. The matching of billiard-balls is important, for extreme accuracy in weight is essential. It is usual to bleach them, as the purchaser—or at any rate the distributing intermediary—likes to have them of a dead white. But this is a mistake, for bleaching with chemicals takes out the gelatine to some extent, alters the quality and affects the density; it also makes them more liable to crack, and they are not nearly so nice-looking. On an average three balls of fine quality are got out of a tooth. The stock of more than one great manufacturer surpasses at times 30,00o in number.

The ivory for piano-keys is delivered to the trade in the shape of what are known as heads and tails, the former for the parts which come under the fingers, the latter for that running up be tween the black keys. The two are joined afterwards on the keyboard with extreme accuracy. Piano-keys are bleached, but organists for some reason or other prefer unbleached keys. The soft variety is mostly used for high-class work and preferably of the Egyptian type.

The great centres of the ivory industry for the ordinary objects of common domestic use are in Great Britain : for cutlery handles Sheffield ; for billiard-balls and piano-keys London. For cutlery a large firm uses an average of some 20 tons of ivory annually, mostly of the hard variety. But for billiard-balls and piano-keys America is now a large producer, and a considerable quantity is made in France and Germany. Dieppe has long been famous for the numberless little ornaments and useful articles such as statu ettes, crucifixes, little book-covers, paper-cutters, combs, servi ette-rings and articles de Paris generally. And St. Claude in the Jura, and Geislingen in Wurttemberg, and Erbach in Hesse, Ger many, are amongst the most important centres of the industry. India and China supply the multitude of toys, models, chess and draughtsmen, puzzles, work-box fittings and other curiosities. Vegetable Ivory, Etc.—Some allusion may be made to vege table ivory and artificial substitutes. The plants yielding the vegetable ivory of commerce represent two or more species of an anomalous genus of palms, and are known to botanists as Phytelephas. They are natives of tropical South America, oc curring chiefly on the banks of the river Magdalena, Colombia, always found in damp localities, not only, however, on the lower coast region as in Darien, but also at a considerable elevation above the sea. They are mostly found in separate groves, not mixed with other trees or shrubs. The plant is severally known as the "tagua" by the Indians on the banks of the Magdalena, as the "anta" on the coasts of Darien, and as the "pullipunta" and "homero" in Peru. It is stemless or short-stemmed, and crowned with from 1 2 to 20 very long pinnatifid leaves. The plants are dioecious, the males forming higher, more erect and robust trunks than the females. The male inflorescence is in the form of a simple, fleshy, cylindrical spadix covered with flowers; the female flowers are also in a single spadix, which, however, is shorter than in the male. The fruit consists of a conglomerated head composed of six or seven drupes, each containing from six to nine seeds, and the whole being enclosed in a walled woody covering forming altogether a globular head as large as that of a man. A single plant sometimes bears at the same time from six to eight of these large heads of fruit, each weighing from 20 to 25 lb. In its very young state the seed contains a clear insipid fluid, which travellers take advantage of to allay thirst. As it gets older this fluid becomes milky and of a sweet taste, and it gradually continues to change both in taste and consistence until it becomes so hard as to make it valuable as a substitute for animal ivory. In their young and fresh state the fruits are eaten with avidity by bears, hogs and other animals. The seeds, or nuts as they are usually called when fully ripe and hard, are used by the American Indians for making small ornamental articles and toys. They are imported into Britain in considerable quantities, frequently under the name of "Corozo" nuts, a name by which the fruits of some species of Attalea (another palm with hard ivory-like seeds) are known in Central America--their uses being chiefly for small articles of turnery.

Many artificial compounds have, from time to time, been tried as substitutes for ivory; amongst them potatoes treated with sulphuric acid. Celluloid is familiar to us nowadays. In the form of bonzoline, into which it is said to enter, it is used largely for billiard-balls; and a new French substitute—a casein made from milk, called galalith—has begun to be much used for piano keys in the cheaper sorts of instrument. Odontolite is mammoth ivory, which through lapse of time and from surroundings be comes converted into a substance known as fossil or blue ivory, and is used occasionally in jewellery as turquoise, which it very much resembles. It results from the tusks of antediluvian mam moths buried in the earth for thousands of years, during which time under certain conditions the ivory becomes slowly pene trated with the metallic salts which give it the peculiar vivid blue colour of turquoise.