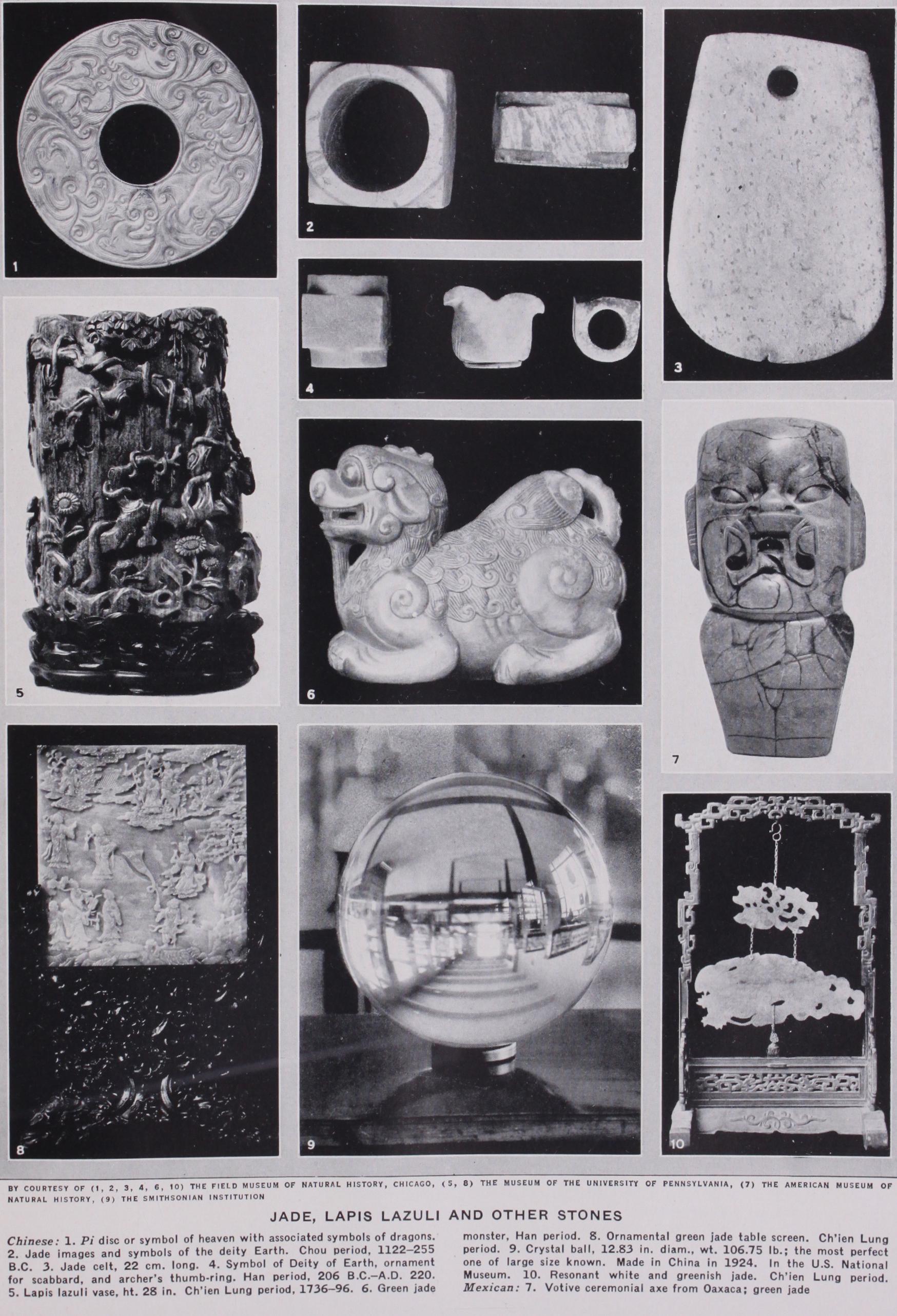

Jade and Other Hard Stone Carvings

JADE AND OTHER HARD STONE CARVINGS.

There are three minerals that are called jade: (I) Nephrite, known since earliest times; (2) Jadeite, described in 1868 by A. Damour, the famous French mineralogist, as new. The stone was of pure white with a faint purple tint. Jadeite is also often the finest jade; it is almost emerald green; (3) Chloromelanite, a dark green, almost black material. Analyses of these three minerals are given below. Although the most intensive investiga tions have been carried on concerning the origin and uses of Jade from the earliest times, it was not until i868 that Damour found that nephrite contained lime and magnesia, whereas jadeite and chloromelanite contained alumina and soda.

Structure.

The structure of jadeite is either granular o, fibrous, the former being more characteristic. It may be studied to the best advantage in such thin, translucent, highly polished objects as bowls, cups or plates. On holding such a specimen against a light each crystal composing it often stands out quite sharply, owing to the fact that the light strikes the surface and cleavages of each crystal at a different angle, thus giving to each a slightly different appearance. The individual grains are some times prismatic in shape, and sometimes equidimensional, with diameters up to 3 mm. in exceptional cases.

The structure of nephrite is characteristically fibrous, and of such a fine grain that the individual fibres are but rarely visible except under the microscope. The fibres in this aggregate are ar ranged in various ways : parallel to one another over considerable areas; in tufted or fan-shaped groups; or curved, twisted, inter locked and felted in most intricate fashion. The coarser visible structure is due to groups of these fine fibres, and is dependent on their internal arrangement. A sinewy or horn-like appearance is extremely common, being visible on both rough and polished sur faces. It seems to be due to the groupings of the fibres into tufted or fan-shaped bundles, sometimes of considerable size, and sep arated from each other by indistinct parting surfaces which are often curved into irregular forms.

pure jadeite should be white, without a tinge of colour. So also an ideal nephrite, containing only lime and magnesia, should be colourless. The colours which actually exist are due to the admixture of other bases in the composition. In general, the green colour of jadeite is due to chromium—the colouring matter of the emerald, but jadeite is never transparent as is the emerald, but is at its best translucent—and that of nephrite to iron. Occasionally, however, anomalies are found, and the analytical data fail to account for the colour or lack of it of an occasional particular specimen.

Lustre.

The lustre of both jadeite and nephrite on fresh fracture is dull and wax-like, with very few reflecting surfaces. Polished jadeite has ordinarily a somewhat vitreous luster, while polished nephrite ordinarily has an oily lustre. This oily appear ance is highly characteristic of many of the green nephrites.

Sonority.

The resonant character of jade has been known to the Chinese since ancient times, and when united with the proper translucency and colour, was regarded as a sure sign of the genuineness of the material. "Sounding-stones" and stones for polishing them are mentioned in the earliest historical records of China (23 centuries B.c.).

The musical jade is often cut in the form of a fish and sus pended by a thong. and when struck the full tones can be heard.

Composition.

The following table shows characteristic chem ical analyses for nephrite, jadeite and chloromelanite.

Occurrence.

Although jade objects in considerable numbers have been found over rather wide-spread areas, there are only a few localities identified where it is known to occur in place. In addition to these there are several others where jade has been found, having been transported there from its place of origin by the action of rivers or glaciers. And finally, there are other localities in which worked jade is found; sometimes in consider able profusion ; in many of these cases the source of the material is pure conjecture, while in others the character of the material is such as to give some indication as to its point of origin. The greatest source of material, and the one that has been studied the most, is in the Kachin country of Upper Burma, near the junction of the Chadwin and Uru rivers, at about 25° to 27° N. lat. and 95° to 97° E. longitude. These quarries were discovered in the 13th century, but it was not until 1784 that trade was estab lished with China, and a regular supply of stone was carried to Yunnan. Since the beginning of the 19th century Mogaung has been the centre of the jade trade in Burma.

Jade occurs in small amounts in several places in Central India, particularly in the State of Rewa. Although conclusive evidence is lacking, the indications seem to show that the Indian jade is all nephrite. One of the oldest and most important of the jade-producing districts is in the K'un Lun mountains, south of Khotan, in south-eastern Turkistan, described by the Sekloge witt brothers. Here are found both nephrite and jadeite, the former, however, greatly predominating. It was from this district that much of the early Chinese material was obtained.

The occurrence of nephrite in Siberia has been known since early in the 19th century, but it was not until 1896-97 that any definite information was obtained. At that time a Russian Gov ernment expedition under von Jaczewski, discovered several oc currences of nephrite in place in the Sajan mountains of central Siberia, between the Belaja and Kitou rivers on the north and south, and the Onot and Urick rivers on the east and west.

Although boulders and worked objects of jade had been known in Europe for many years, it was not until 1884 that it was dis covered in place by Traube at Jordansmdhl, and a few years later at Reichenstein, in Silesia. This material is nephrite. These discoveries were supplemented in 1899 by that of Dr. George F.

Kunz, who found at Jordansmdhl one of the largest pieces of nephrite that has ever been quarried. This specimen, weighing 4,812 lb., is now in the American Museum of Natural History in New York city. Although several nephrite boulders have been found in glacial deposits in other localities, no other occurrences of nephrite in place are known in Europe. No occurrence of jadeite in situ is known in Europe but it is mined extensively in Mogoung, Burma.

In North America nephrite has been found in place in Alaska, about 15o m. above the mouth of the Kowak river, at 67° 5' N. lat. and 158° 15' W. longitude. Boulders of nephrite have also been found along the lower Fraser and the upper Lewes rivers in British Columbia. While material has not been found in place in either of these localities, all indications lead to the conclusion that the boulders had originated in the immediate locality.

Nephrite has long been used by the natives of New Zealand in tools, ornaments and magnificent ceremonial implements of various kinds. The material occurs in boulders chiefly on the west coast of South island, although other localities of lesser impor tance are known. Nephrite is found in place on the west coast of the island of Uen, off the south-eastern point of New Caledonia.

Although a fondness for jade is almost a national characteristic in China, there are no known occurrences in China. Most of the material used by the Chinese has come from either Chinese Tur kistan or Burn- a. It is also possible that some Siberian or New Zealand material has been used.

Of the many thousand pieces of carved jade from China and India, with the possible exception of the small buttons, there are scarcely two pieces alike. The artist studied the piece of rough material to discover what could best be made of it and then made the design to fit the piece. The result is that most of the pieces are artistic and the lapidary work unique. They stand in an art by themselves.

In Europe worked objects of both nephrite and jadeite have been found over wide areas. Nephrite has been found particu larly in the vicinity of the ancient lake villages of Switzerland. Jadeite objects were more widely distributed in Germany, France, Belgium, Switzerland and Italy. In Mexico and Central America large numbers of jadeite objects have been found. While these are the chief localities, there are also numerous others in which either jadeite or nephrite objects, or both, have been found, with out clear evidence as to the source of the material.

There have been two historic debates concerning the occur rences of jade, both of which extended over many years. The first was concerned with the question as to whether jade was to be found in place in Europe, or whether the material used by the prehistoric peoples of central Europe was all brought from the outside, either by glacial action or by commerce. This question was definitely settled by the discoveries of Traube and Kunz, described above. The second concerned a similar question with regard to Mexican and Central American material. No jade has as yet been discovered in place in these countries, and many have thought that its presence and use there was an indication of ancient contacts between these peoples and the Orient. While this theory has been actively promulgated by many adherents, no definite proofs have as yet been forthcoming on either side.

Uses.

It is remarkable that men even from the earliest times, whether the prehistoric lake-dwellers of Europe, the ancient in habitants of the valley of Mexico, the aborigines of north-west America, the natives of New Zealand, or the people of China, found small blocks or boulders of jade, of a wide variety and range of colour, but which they had the acumen to determine were of a hard, tough material suitable for axes and other utili tarian purposes, as well as for artistic uses. We know that there was prehistoric jade in the graves in China, and more would have been found had there not been a sentiment against opening up the buried remains in that country. Later on jade was selected as a material possessing many of the most charming qualities of beauty, lustre and toughness, so that many thousands of pieces of jade, from the purest white and the palest green to a dark green, have been carved in the designs of many countries, pieces that in many cases have required years to make. As an example of the endless patience used in the execution of such pieces, there is a necklace of ioo links with a pendant, all of one un broken piece in the American Museum of Natural History. And in the F. 0. Mathieson bequest to the Metropolitan Museum of Art are four covered vases which open in the centre for fruits, the cover and lower part all of one unbroken piece.

The greatest rulers of the East have treated this stone with a reverence attributed to no other material. The poems of emperors have been recorded on tablets of jade and the great fish bowl in the Bishop collection, weighing 1 20 lb., has the poem of an emperor on its inner base. The respect and reverence placed in this stone is well deserved, and if the Chinese had all the articles that were originally in China, they would form a collection not rivalled by that of any other nation or by that of any other material.

Great masses of a wonderful material stained brown by con tact with bodies, or stained brown to look as if they had been buried with bodies, is known as tomb jade. Some of it is believed to date back 20 centuries. The Chinese have obtained some of the most magnificent jade and frequently have spent as much as a year searching for a single piece. Some splendid examples of these may be seen in the Heber R. Bishop collection in the Metropolitan Museum of Art; the Johnson collection in Philadelphia, gifts in memory of Dr. George Byron Gordon. Other specimens are in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the British Museum, the Louvre and in Berlin, and many other places throughout the world.

Jade of different colours was used in China for the six precious tablets employed in the worship of heaven and earth and the four cardinal points. For the worship of heaven there was a dark-green round tablet, and for the earth an octagonal yellow tablet ; the east was worshipped with a green pivoted tablet, the west with a white "tiger tablet," the north with a black semi circular tablet, and the south with a tablet of red jade. The yellow girdles worn by the Chinese emperors of the Manchu dynasty were variously ornamented with precious stones, accord ing to the different ceremonial observances at which the emperor presided. For the services in the temple of heaven, lapis lazuli was used; for the altar of earth, yellow jade; for a sacrifice at the altar of the sun, red coral ; and for ceremonies before the altar of the moon, white jade.

Jade amulets of many different forms were popular with the Chinese, as were also rings, ear-rings and beads, but in general, jade was much more used for decorative pieces than for articles of personal adornment. While in other localities jade has been used extensively for axes, adzes, knives and other purely utilitarian objects, for which its hardness and toughness make it peculiarly applicable, the reverence with which the stone was held in China seems to have precluded its use in such fashion, and the purely utilitarian is almost entirely absent in the Chinese uses; here the ornamental features greatly predominate, and where the utilitarian features do come in, it is usually in a vase, cup, plate or bowl, or some similar object, in which beauty may be combined with utility. It is possible that the pre-Chinese used jade for axes and celts but the later Chinese ornamented and recarved these.

The jade objects found in Mexico and Central America are frequently of a rich, almost emerald green colour, and there have been thousands of pieces found, from the smallest fragments to the great adze weighing 16 lb., which is now in the American Museum of Natural History. Much of the Mexican material has been used in religious ceremonies, but utilitarian and orna mental material is also found. The outstanding find of jade objects in Mexico was at the sacred well of Chitzinitza in Yucatan, into which had been cast as votive offerings hundreds of pieces of jadeite. This valuable discovery was made by Dr.

E. H. Thompson of the Peabody Museum, who spent a lifetime in this region.

In New Zealand, where the most primitive methods held, jade was in high esteem among the Maori chiefs, who had their patou-patous (small axes which they held under the arm) per forated at the upper end and ornamented with jade. Hei tikis crudely carved small human figures—were made of jade with narrow slant eyes of abalone shell, usually facing to the right, but occasionally to the left. These were worn as amulets and frequently handed down from one generation to another, as the material is almost indestructible.

Commercial Value.

Jade of medium colour cut into the form of bead necklaces sell as low as $50, but exceptional quality commands correspondingly high prices. An emerald green feitsuinecklace, 3o in. long, of 125 beads, weighing 304 carats (approxi mately 2 oz. Troy), with a centre bead -1 in. in diameter, and end beads 6 in. in diameter, commanded a price of $8o,000; larger necklaces have brought more than $1oo,000. Exceptional pieces have been made into brooches at prices from $i,000 to $5,000. Ring stones cut cabochon on top sell at from $roo to $2,000 each. The thumb rings worn by the Chinese nobility frequently commanded over f r ,000, and, it is claimed, even up to £2,000 for the ring which is a relic of the time when the archer drew his bow with a thumb ring of wood, horn, agate or jade. An exceptionally fine ring of this character was worn by the former ambassador to the United States, Wu Ting Fang; this ring had been originally worn on a larger hand, and had a lining of fine gold to fit it to the finger of the new wearer of the ring.

Minerals and Imitations Mistaken for Jade.

Under this heading we have three types of material to consider : those which through a close similarity to jade in colour, toughness and lustre may be mistaken for the true material ; those which have been stained, coloured, or otherwise treated in order to enhance this similarity ; and those that are purely and entirely artificial imi tations. The natural minerals that resemble jade most closely are those having a similar chemical composition, i.e., complex silicates, but various forms of pure quartz and a few other minerals also fall into this group. The determination of the hardness and specific gravity of the specimen is usually sufficient to differentiate between the true and false jade. Jadeite has a hardness of approx imately 7.o and a specific gravity of 3.2 to 3.4; nephrite has a hardness of 6.5 and a specific gravity of 2.9; very few other minerals show this particular combination of hardness and gravity.

Saussurite is probably the most important of these materials easily mistaken for true jade. It is a compact, tough, heavy mineral with a hardness and gravity almost identical with jadeite, and this makes the differentiation difficult. Next in point of resemblance is fibrolite, or sillimanite. Like saussurite it has the hardness and gravity of jadeite, but it is readily identified chemi cally, being a practically pure silicate of aluminium. The Alaskan natives have frequently used pectolite for jade. This has a gravity close to nephrite, hut is much softer. Wollastonite, occasionally confused with jade, can be detected by its softness as compared with jade. A number of different varieties of feldspar sometimes resemble jade. These are also lower in gravity than jade, and most of them are lower in hardness. Chief among these are amazon-stone, eupholide, saccharite and labradorite.

Jadeite is classed chemically as a pyroxene, and in the same family of rocks are several other minerals quite similar to it, particularly omphacite and eclogite. These have the gravity of jadeite, but are softer. Diopsite has the hardness of nephrite and the gravity of jadeite, but can be distinguished by the difference in cleavage. Nephrite is an amphibole rock, and in this group we find also actinolite closely resembling it, but differing in the texture of the fibrous structure.

Outstanding among the green minerals is the emerald, a green variety of beryl, and it is possible for an opaque emerald to be mistaken for jade, though it may be readily differentiated by its higher hardness, lower gravity, and the presence of beryllium in its composition.

One of the minerals that most frequently resembles jade, especially in the East, is a variety of serpentine known as bowen ite. This has both hardness and gravity higher than the average serpentine, but still lower than nephrite. It has a texture similar to that of jadeite, and where the colour was lacking, it has been stained in imitation. Antigorite and williamsite are translucent varieties of serpentine of a rich, green colour. Although the latter is much harder than the former, both are far softer than jade. Williamsite has an intense rich green colour.

A material recently placed on the market as South African jade is really a compact, translucent, green garnet. It is higher than jade in both gravity and hardness. Numerous forms of pure quartz may, by their colour and opacity be mistaken for jade, particularly prase, plasma, chrysoprase, jasper, aventurine and moss agate. All these have a lower gravity than jade, and a hardness equalled only by the hardest jadeite. The minerals most difficult to differentiate from jade are prehnite, epidote, vesuvianite and agalmatolite. Prehnite has the hardness of nephrite and a gravity close to the lower limit for nephrite; its colour is good, but it lacks lustre, and is more brittle than true jade. Epidote has the hardness of jade, and a gravity in the upper limits of the range for jadeite, from which it may be dis tinguished by its strong cleavage, a more vitreous lustre, and the presence of considerable iron in its composition. Vesuvianite has about the same hardness and gravity as epidote, and like it has a more vitreous lustre than jade ; it is also more brittle, and has an uneven fracture. Another form of vesuvianite is named calif ornite by the author. Agalmatolite is one of the minerals most frequently sold to the uninitiated in China, under mis representation as jade. It is readily detected, however, by its extreme softness, and less readily by its lower gravity. It has a compact, fine and homogeneous structure that makes it ideal for carving, but its colour is such that it is usually stained green in imitation of nephrite. It is stained in many other colours.

Under some conditions turquoise (a phosphate), malachite (a copper carbonate), and mossotite (a lime carbonate), may be mistaken for jade, but identification is simple in all cases by hardness, gravity and chemical composition.

China probably takes the lead over all other countries in the number of substances that have been mistaken, or substituted, for jade. This is due partly, particularly in earlier times, to lack of exact mineralogical information and technical methods of identi fication, and partly to the natural tendency toward substitution for, or imitation of, a highly prized and equally highly priced material. Prominent among these fabrications is the so-called pink jade, which, if truly pink, and not the pinkish-lavender characteristic of some Burmese jade, has always turned out on careful examination to be quartz, aniline dye absorbed into fine cracks and fissures in the material. This may be detected by rub bing the piece with cotton moistened in alcohol.

Another important type of fabricated material is made from a heavy lead glass, carefully tinted and most ingeniously polished to give the characteristic jade-like lustre by first giving a high polish and then deadening this to the desired degree by a fine hard powder. One form of this is made in imitation of the white and green "imperial jade" of China, and may be found in bracelets, ear-rings and other trinkets, in almost every Chinese shop. An other type is all green, in imitation of the Burmese jadeite, and another, known under the name of pate de riz, is white with a faint bluish-green or bluish-grey tint. This same method of preparation of the surface has also been used on varieties of green quartz to simulate the lustre of jade.

Descriptive Literature.

Of all the Chinese works on jade the most interesting and most remarkable is the Ku yu t'ou pu, or Illustrated Description of Ancient Jade, a catalogue divided into books and embellished with nearly 700 figures. It was pub lished in 1176, and lists the magnificent collection of jade ob jects belonging to the first emperor of the Southern Sung dy nasty. One of the treasures here described was a four-sided plaque of pure white jade, over 2 f t. in height and breadth. The design was a figure seated on a mat, with a flower vase on its left and an alms-bowl on its right, in the midst of rocks enveloped in clouds.

The most complete and modern descriptive work on jade is the catalogue of the H. R. Bishop collection of jade in the Metro politan Museum of Art. This is the most remarkable collection of jade in existence, and the two great volumes of the catalogue and accompanying descriptive matter fully match the collection itself in magnificence. The catalogue was illustrated by some of the greatest artists of the time. The volumes were not sold, but were distributed to libraries and museums here and abroad, to a few royal personages, and to several of Mr. Bishop's relatives. The author of this article devoted 12 years of his leisure to the mineralogical studies and the guidance of the scientific study of the many experts whom he called upon to aid in this great work.

Among the other hard stones that have been cut, engraved and polished along lines similar to jade are the various forms of quartz (rock crystal, agate, carnelian, chalcedony and jasper) and the softer but highly valued materials, such as malachite, fluorite, rhodonite and lapis lazuli. All of these materials lend themselves well to this type of treatment, and in fact, as has already been mentioned, many of them have in some form or other frequently been mistaken, or substituted, for jade.

Of all the hard stones, probably rock crystal and agate have been most used, and in a wide variety of forms. Crystal has been particularly popular in vases and other ornamental forms, and as crystal balls. The outstanding example of the latter form is a ball 3o in. in diameter, made from Burmese crystal, and finished in Japan.

Jasper (q.v.) found in Russia is not excelled by that of any other country. It has a grey, almost putty colour, and a texture of wonderful homogeneity. Of this material tables and other pieces are made which are unequalled by any other lapidary work in existence. Aventurine, a quartz containing brilliant scales of other coloured minerals, is found in the Ural mountains, and has been used in vases up to 6 ft. in height. Rhodonite (q.v.) is a member of the pyroxene group, the same family to which jade ite belongs ; it is usually a beautiful rose or red colour, but is sometimes a light brown. The name rhodonite, from the Greek word rhodon, rose, suggests its colour. The mineral has been used as a gem, and for various types of ornamental objects; the sarcophagus of the Tsar Alexander II. was constructed from rhodonite found near Ekaterinburg (now Sverdlovsk). It is also found associated with manganese deposits in other parts of the world, its composition being manganese silicate. It has a hard ness between 5 and 6, and a specific gravity of 3.5 to 3.6. It is slightly translucent, has little lustre, but takes a fairly good polish. Rhodonite was especially the imperial stone of Russia, and is there found in great masses.

One of the tsarinas of Russia wished an egg cut of pure rose rhodonite, without a streak of black in it, and one ton of this material was cut without finding a single piece large enough to cut the egg which did not have a streak of some kind in it.

It is strange that two great colours have been generally known and appreciated throughout the ages, one a royal blue and the other a royal green—lapis lazuli and malachite. Both of these being opaque, very wonderful pieces can be made from them, as they can be cut into thin sections, from J to 3. in. in thickness, and then strengthened by cementing them to a suitable backing, either slate or some material that does not contract or bend.

Lapis lazuli (q.v.) is one of the oldest of the gem materials, having been used for 6,000 years, and the supply has been con tinuous. During this entire period the chief sources of supply have been Persia and Afghanistan. It is sent to the markets in masses of from i to 5 lb. One mass of i6o lb. reached the United States several years ago, and another of 30 lb. was found in the Oxus river district of Afghanistan. One of the results of the visit to Europe of King Amanullah in 1928 was a grant to a German firm of a monopoly for the exportation of Afghan lapis lazuli.

Obsidian (q.v.), or volcanic glass, is found in great quantities in the Valley of Mexico. Some wonderful chipping, grinding and polishing has been done on this material. One of the best ex amples is the Father Fisher knife in the Blake collection in the National Museum in Washington—a knife 19 in. in length. Another fine example is a mask, almost the size of a human face, Ornaments for the ear and for the lips were frequently made with the thinness of paper and polished exquisitely and carved in the centre. Mirrors i in. thick were made of this material, some of which may be seen in the American Museum of Natural His tory that are 15 by 12 inches.

Emeralds (q.v.) were looted and mined in great quantities by the Spanish when they invaded Peru; these stones were also brought from the mines of the United States of Colombia. Five cases are believed to have been lost at sea. Large assignments were shipped to Spain and then sold in Paris. The more perfect stones were kept by the Spanish and French and the rest were shipped to India, Persia and Turkey, where the natives engraved them to hide the flaws. For many centuries they were known, and still are, as Indian emeralds. It is quite possible that these sustained the expense of the great traveller, Tavernier, who took many of these to India where he traded them for rubies from the Burmese mines and then sold the rubies in Europe. Louis XIV. is said also to have financed him. Some of these—very large ones—were found when the British captured King Thebaw's palace at Rangoon and they are now in the Indian museum at London. Several hexagonal sections of the crystal were used, over three inches. There is hardly an Indian, Persian or Turkish ruler who does not possess some of these emeralds even to the present day, and frequently an encabochon unengraved emerald is worn in one ear and an encabochon ruby in the other ear. These emeralds must have been sent to Turkey and Russia eastward by the thousands and it is very possible that Tavernier is responsible for the placing of many of them, and the great quantity that he had made his great trip possible. Among the Russian crown jewels and in some of the jewels of the Ourejene, Kremlin, and the treas ury of the bishops are many fine emeralds, one of which the writer saw which was more than an inch across and excellent in colour. (See also JADE, GEMS, JEWELLERY.)