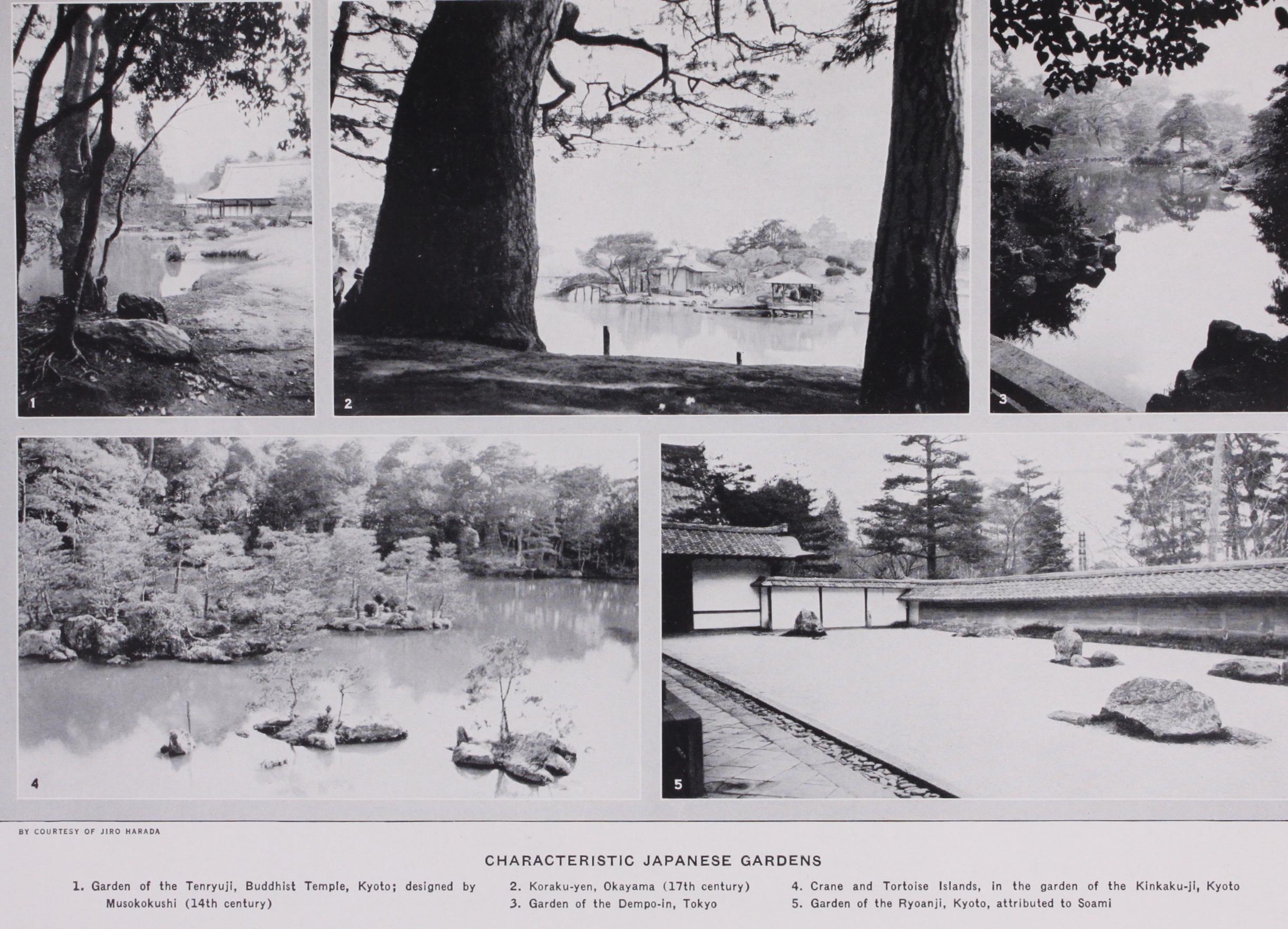

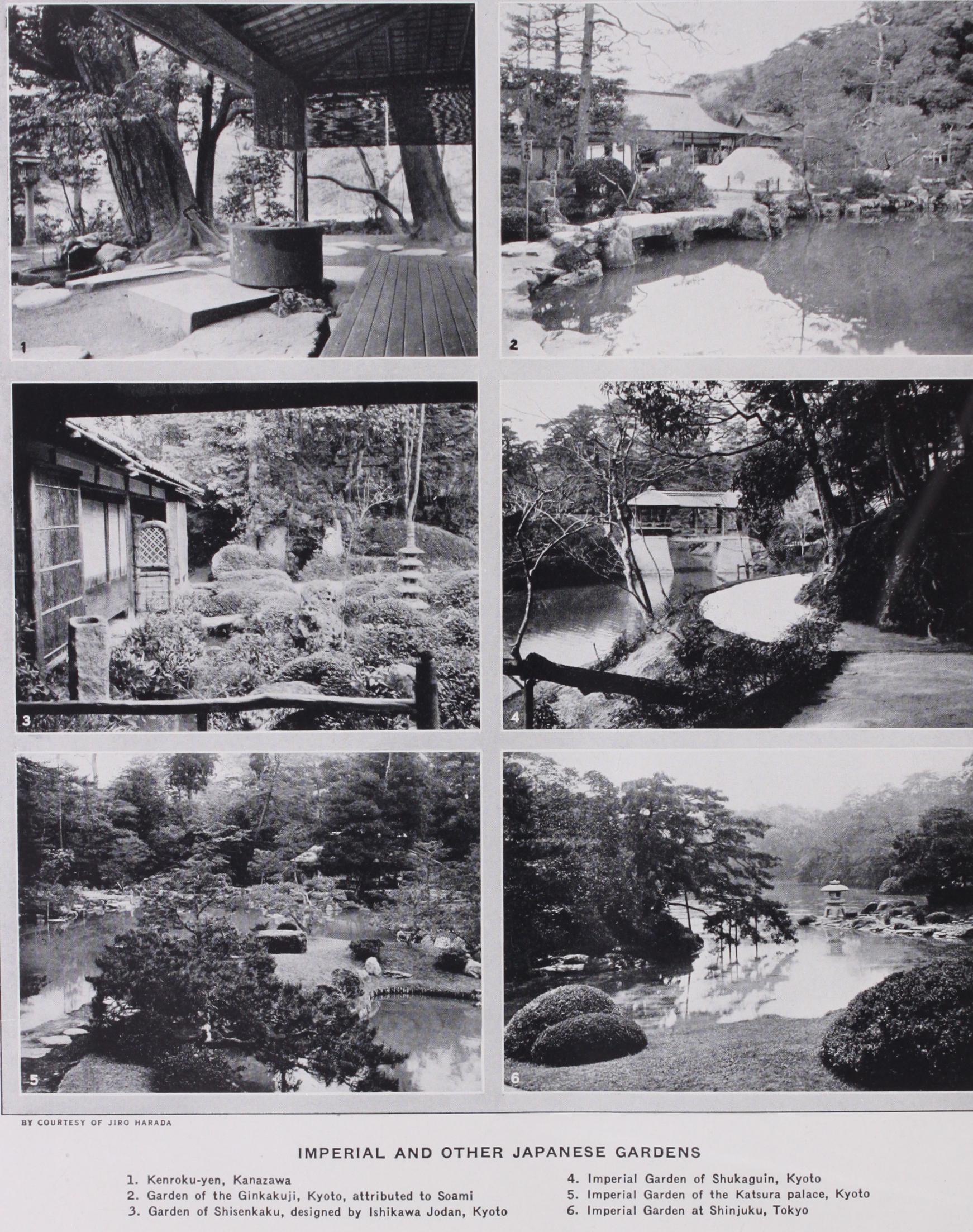

Japanese Gardens

JAPANESE GARDENS. The art of garden-making was probably imported into Japan from China or Korea. Records show that the imperial palaces had gardens by the 5th century, their chief characteristic being a pond with an islet connected to the shore by bridges—as is shown later by mentions of the em peror ShOmu's (724-748) three gardens in Nara. During the Heian period (782-1185), when the symmetrical shinden style of architecture prevailed, the main garden (as often, even to-day) was laid out on the southern side of the house, always with hills and a pond with an island. However, with the change in domestic architecture of the Kamakura period (1186-1335), came modifi cations of the garden. Learned Zen priests, who assiduously stud ied the art of garden-making, gave Buddhistic names to different rocks in the design, and linked religio-philosophic principles with the rules governing it. Other cults and superstitions crept in also, further complicating the design.

With the supremacy of the Ashikaga dynasty came popularization of gardens, which were designed to be en joyed from within as from without, opening a new era in the development of garden-making. The subjective mood became dominant, and the gardens reflected individuality. People de manded shibumi in their gardens—an unassuming quality in which refinement underlies a commonplace appearance, appreciable only by a cultivated taste. Aesthetic priests, "tea-men," and connois seurs devised new forms of gardens for cha-seki, the little pa vilions or rooms built for cha-no-yu (tea-ceremonies), and a spe cial style developed which revolutionized Japanese garden art.

Styles in Gardens.

The vogue of designing in the three de grees of elaboration—shin, gyo and so (elaborate, intermediate and abbreviated)—was adopted also for gardens. Many splendid gardens were produced in the Momoyama (1574-1602) and Edo (1603-1868) periods. However, the centre of garden activity gradually shifted from Kyoto to Edo, the seat of the Tokugawa Shogun. One development was a utilitarian phase ; e.g., the duck pond in the Hama detached palace in Tokyo, and the cultivation in the Kairaku-yen at Mito of reeds for arrow-shafts, and plums for military supplies. Feudal lords generally had fine gardens in their provincial homes as well. Quite a number of gardens have survived the abolition of the feudal system after the Restoration of 1868, when so many celebrated gardens perished through neg lect or were sacrificed. The establishment of public parks, which were not unknown even in feudal times, has been specially en couraged throughout the country since 1873. Gardens of Western style came with other Western modes but made little headway. The great earthquake and fire of 1923 demonstrated the utili tarian value of the Tokyo gardens. Tens of thousands found safety in the parks and in the large private gardens scattered throughout the city.

Classes of Gardens.

Japanese gardens are generally classi fied, according to the nature of the ground, under two heads: tsuki-yama (artificial-hills) and hira-niwa (level-gardens), each having special features. Tsuki-yama consists of hills and ponds, and hira-niwa of a flat piece of ground so designed as to repre sent a valley, a moor, and so on, and tsuki-yama may embrace a portion laid out as hira-niwa, both types being treated in the three degrees of elaborations already mentioned. Hill-gardens as a rule include a stream and pond of real water, but in the kare-sansui (dried-up landscape) style, while rocks are composed into the form of a waterfall and its basin, and of a winding stream and pond, gravel or sand is used to symbolize water, or to suggest the temporary phase of a naturally dried-up landscape. In extreme examples, where prime importance is given to rocks, and trees are absent, a real "rock garden" may be said to result. There are also styles known as sen-tei (water-garden) or rin-sen (forest water), and, in level gardens, bunjin-zukuri (literary men's style), a very simple and small type, originated by dilettanti in Chinese literature. The tea-garden or roji (dew-ground or passage) as it is called, is another distinct style evolved to meet the requirements of the tea ceremonies, as already mentioned. Genkwan-saki (front of entrance) or house-approaches have always claimed special treatment—a simple curve, wherever possible, partially to conceal the entrance to the house and give character to its front view.

Characteristic Features.

The characteristic features of a Japanese garden are the waterfall, of which there are ten or more different modes of arrangement, the spring and the stream to which it gives rise, the lake, the hills built up from the earth excavated when its basin is dug, the islands with many varieties of bridges, and the natural stones which constitute the skeleton of the garden. The selection and effective distribution of thesestones are the prime consideration and have been endlessly experi mented with and deeply pondered, the cream of such experi ments in composition being handed down by means of drawings. The studied irregularity of the arrangement of the stepping-stones in the cha-no-yu garden, wherein beauty and use are combined, is a noteworthy element of garden-design. In modern Japanese gar dens flowers are few and evergreens popular. The significance here is that simplicity, restraint and consistency are sought rather than gaiety, showiness or the obvious variations of the seasons, and subtle gradation in the tones of the foliage is preferred to the changing aspect of deciduous trees, though with some exceptions such as maple trees. As in the case of stones, trees must be dis tributed in the garden in harmony with their natural origin and habit of growth. Of garden furniture and accessories, the well, decorative and useful alike, the stone water-basin, endless in variety, stone lanterns, figures and pagodas, arbours and summer houses, are the most characteristic, together with gateways and fences, particularly the widely varying sode-gaki (sleeve-fence) attached to the side of the house to screen certain portions, and used to blend harmoniously the natural beauty of the garden with the human art displayed in the architectural features of the house.

Ideals and Aims in Garden Design.—The ideals of garden designing have often been modified during its long history, being influenced by the prevailing thought of each period. At one time eminent Zen priests designed gardens in accordance with the prin ciples which lay at the base of their philosophical teaching; at another, painters became deeply interested and designed gardens as though they were painting landscapes on silk. In the course of history the objective standpoint in garden-making gave place to a subjective impulse. Various philosophic principles and religious doctrines were embodied in the making of gardens, not so much to interpret those particular principles and doctrines as to explain the aesthetics of garden design, and more particularly of the dis tribution of natural rocks, by illustrations drawn from familiar philosophic principles. Long after such principles have ceased to sway the mind of the people, the terminology survived, preserving a repertory of symbols. The laws of direction, of harmony, of the five elements, the principles of cause and effect, of the active and passive, of light and shadow, or of the nine spirits of the Buddhist pantheon, as well as superstitions of all sorts, still continue to influence to some extent the general design of gardens.

The aim is to bring man closer to Nature, and all manner of means have been resorted to in the effort to realize it. Some of the master-designers reproduced in miniature famous scenes of China and Japan. They planned the garden and planted trees to give the illusion of a view extending over and beyond its own immediate confines, but at the same time they so designed it as to be a secluded and sylvan retreat from the world, great ingenuity being displayed in both directions. In some instances, with only a few stones in a narrow strip of ground, a great expanse of landscape has been included as a background. In another instance, Rikyu, in his garden at Sakai, obstructed the open view of the sea in such a way that only when the guest stooped at the stone water basin to wash his hands and rinse his mouth preparatory to enter ing the cha-seki, did he catch an unexpected glimpse through the trees of the shimmering sea, thus being suddenly made to realize the relation of the dipperful of water lifted from the basin to the vast expanse of sea, and of himself to the universe. The Japanese have tried to emphasize in their gardens the charm of restraint, and of beauty so concealed that it may be discovered individually, thus providing that thrill of joy to the soul which comes from doing a good deed in stealth. Thus, at least in its ideals, the Japanese garden, which has always been part and parcel of the home, by no means stops at merely creating and arranging beautiful spots, but aims at being natural that it may satisfy the human craving for nature, and, by supplying peace and repose, may be a retreat in which man's spirit can wander and find spiritual recreation and sustenance. (See also Box KEI ; BONSAI; BON-SEKI ; HAKO-NIWA ; JAPANESE ARCHITEC TURE.) See J. Conder, Landscape Gardening in Japan (1893) ; J. Harada, The Gardens of Japan (1928). (J. HAR.)