Japanese Sculpture

JAPANESE SCULPTURE. It is surprising that so many pieces of sculpture should still be preserved in Japan when we know that they have been housed in wooden buildings which have been reduced to ashes again and again by recurrent conflagrations. Such preservation has been mainly due to the important part sculpture has always played in religion, and in later times to the reverent attitude towards those works of art tolerated by the "tea men" when the cha-no-yu (commonly known as the tea cere monies) came into the life of the people in the 15th century. A commission was created in 1897 for the systematic preservation and care of works of art, and up to the beginning of 1928 no fewer than 1,800 pieces of sculpture, together with about an equal number of objects of aesthetic and historical value, have been scheduled as "national treasures" in addition to the I,IOO old buildings which likewise have been placed under "special State protection." Few examples in stone remain of the sculpture of the pre Buddhist period. The stone warriors discovered in the province of Higo date from the second decade of the 6th century A.D. and are rude in workmanship. There survive, however, from this early period a large number of haniwa, or baked clay figures of men, women, animals and birds, which decorated the burial mounds of illustrious personages. The expression of peace and amiability on the faces of all these human figures is noteworthy.

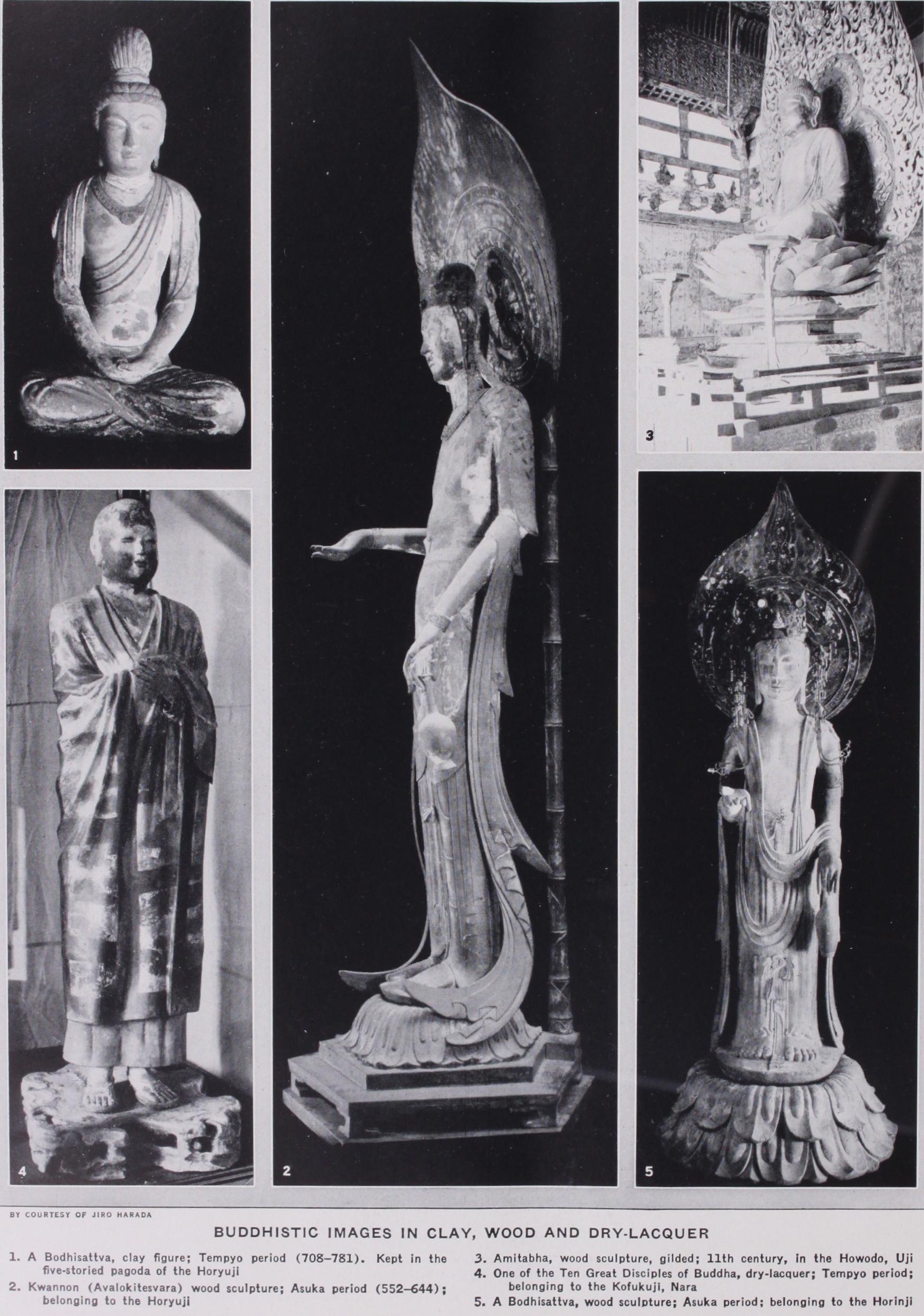

Historic Period.—The real history of Japanese sculpture may be said to date from the official introduction of Buddhism from Korea in A.D. 552. Fortunately, there are preserved to this day a comparatively large number of Buddhist images of that time. Most of them are of impassive character, reminiscent of the North Wei dynasty, and showing in bronze and wood the technique of stone. Naturally, there are some that are of Korean type, as Japanese of Korean descent were among the noted sculptors of that time. Among the relics of this period mention may be made of many bronze figures in the Imperial Household collection, in cluding a Kwannon (AvalOkitesvara) bearing the date 591, and the famous group of 48 figures. Among others, there is a gilded bronze Sakyamuni, dated 623, with two attendants, in the Kondo of Horyuji, where the group was originally placed by the sculptor Tori, who modelled them. A standing image of Kwannon, of a Korean type, also belongs to the Horyuji monastery, and in the Dream hall there is another wooden image of Kwannon attributed to Shotoku Taishi ; there is also in the nunnery of Chilguji, close by, a seated image of Nyo-i-rin Kwannon, and a similar figure is in the temple of Koryuji at Uzumasa. The peculiarly Japanese grace softening the stiff uncouth style of the last two pieces is remarkable.

A noticeable development occurred in the sculpture of the HakuhO period (645-707), when magnificent figures in bronze were cast, as may be seen from the Yakushi (Bhaishajyaguru) trinity in Yakushiji of Yamato, all measuring about Io ft. in height, and with Aryan rather than Chinese features. A masterful achievement in refined workmanship may be seen in the bronze Amitabha trinity, which belonged to Tachibana Fujin.

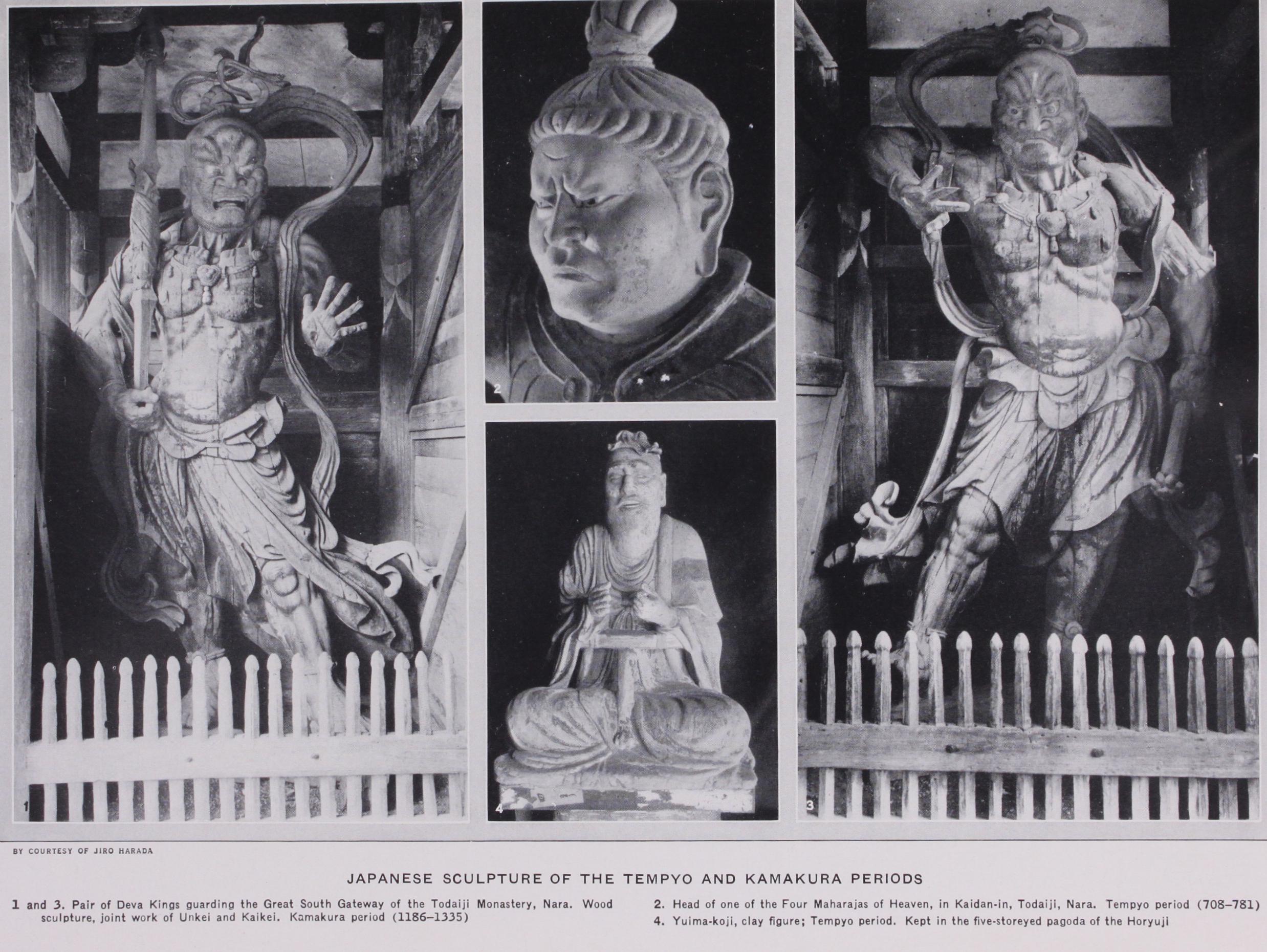

Tempyo (708-781) was a great period of sculpture when thou sands of Buddhistic images were created in clay, wood, dry lacquer and bronze. The gigantic seated Buddha of TOdaiji, measuring some 53 ft. in height, was cast at that time, though the head had to be recast twice after being destroyed by fire. The four Deva-kings in the Kaidan-in of the Todaiji monastery and the Twelve Gen erals in Shinyakushiji are excellent examples of the period in clay. Miroku Bosatsu (Maitreya) of HOryuji, and the Eight Genii and the Ten Great Disciples of Buddha in Kofukuji, are among the works in dry lacquer, a technique peculiar to this and the next period. Power and strength may be said to characterize the sculp ture of this age, with a tendency to combine realistic with idealistic elements.

The new sects of esoteric Buddhism, Tendai and Shingon, infused a new life into sculpture in the early Heian period (78a 888), many learned priests and talented sculptors devoting them selves to the production of deities in wood so faithful to the originals in the sutras that they long served as models for forms. Many of the masterpieces of this period are preserved in the temple of Toji and Jingoji in Kyoto, as well as in Muroo-dera in Yamato. The best of them are executed in bold and deep-cut lines and are characterized by great dignity. The exquisite statue of the I-faced Kwannon in the Hokkeji nunnery, commonly attributed to the Tempyo, may also be included among the works of this period.

The Fujiwara Periods (889-1183).

At the beginning of the early Fujiwara period (889-1068) sculptors simply followed in the footsteps of their predecessors, until the appearance of the great master, Who. With the assistance of his pupils, Jocho completed a wooden image of Dainichi (Mahavairocana) 32 ft. high for HoshOji, and hundreds of smaller statues. As in archi tecture, the nationalist spirit was at work in sculpture, modifying the original type of Buddha. The face became fuller, with narrowbenevolent eyes, the lines of the robes took an eloquent flow, the whole figure was realistically represented in beautiful proportions, and the colouring was in accordance with a refined taste, all tend ing to nobility and dignity. Among the best examples of works of the period now remaining are : the Amitabha of HOkaiji in Yama shiro, the 9 statues of Amitabha of Joruriji and the Amitabha trinity of Sarzen-in both in Kyoto and the Amitabha in HOwOdo at Uji.

In the later Fujiwara period (1069-1183) a tendency became apparent in the direction of excessive detail, elegance and over emphasis, and by the end of the Fujiwara period the work had become weak and effeminate. In the products of masters only were vigour and life maintained. The use of cut-gold for decora tion (leaf-gold cut into strips and applied to form patterns, etc.) which began to be an important factor in early Fujiwara, became profuse towards the close of late Fujiwara.

From Kamakura to Momoyama (1186-1602).

The over refinement and effeminate delicacy of feeling developed by the end of the preceding era was succeeded in the Kamakura period (1186-1335) by something bold and strong, the romantic giving place to the dramatic. Naturalistic representations were intro duced, such as the insertion of rock crystals for the eyes and the use of strong colours and cut-gold for the decoration of robes, etc. There were two elements to be noted : a new school with Sung elements, and the tenacious Fujiwara school of Kyoto which was not eclipsed till the period that came after Kamakura. There was a style in which the figures were of short stature and irapressive force, and another in which they were represented in lorig, flowing robes that partly overhung the pedestal; both these styles reveal the influence of Sung and Yuan. Though wood was the most common material, the masters worked in bronze as well. A great masterpiece is the big bronze Buddha at Kamakura, seated in perfect serenity, with eyes whose gaze penetrates into the very soul of each worshipper standing before him. Two master sculp tors, Kaikei and Unkei, made themselves famous, not only during this period, but throughout the history of Japanese sculpture. Their joint work may be seen in two Deva-kings guarding the great south gateway of Todaiji.

In the NambokuchO (1336-93) and Ashikaga (1394-1573) periods the art of sculpture stagnated, though some dignified por traits in wood were produced. Representation reached the extreme of elaboration, and the statues of deities became more human in character. The Kwannon in the Tokyo Imperial Household museum, minutely decorated all over with coloured lacquer and cut-gold, with rock crystals inlaid for the eyes and lips, may be considered one of the best examples of the period. It is to be noted that many sculptors of the time turned their attention to carving masks used in the No drama, which flourished among the feudal lords.

The aversion from monks shown by Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi resulted in the destruction of many temples, and in the Momoyama period (1574-1602) circumstances were not at all conducive to the development of Buddhistic sculpture. The great castles and palaces, however, were profusely decorated externally and internally.

Modern and Recent Sculpture.

During the peaceful Tokugawa regime (1603-1867) the talent of sculptors was mainly turned to the production of articles of luxury for the people. No masks required a high degree of skill, and a great demand was created for smaller carvings in wood and ivory, such as netsuke, or the ornamental piece fastened to the end of the cord attached to the tobacco pouch or the inro (small medicine cases hung from the sash). With the restoration of the temples, many images were carved, but these were merely reproductions of the old works of art. Work characteristic of the period is to be found, however, in the carvings adorning temple buildings and shrines. Some localities, such as Kyoto and Nara, produced peculiarly characteristic wooden dolls.

With the restoration of power to the imperial throne in 1868, which was followed by the abolition of the feudal system, a change came over Japanese sculpture. The introduction into Japan of Western clay-modelling, first taught at the Tokyo School of Arts, gave a great impetus to the development of sculpture in Japan. Not only has the new technique found a large number of followers, but the traditional wood-carving has received a great stimulus which has led to improvement. The traditional school, however, still continues to work mainly in wood, while the ex ponents of foreign ideals choose bronze, marble and clay, as well as wood. In spite of the aggression of the younger school, the older school courageously struggles to hold its own and to pre serve that which is characteristically Japanese. (See CHINESE SCULPTURE; IVORY CARVING, JAPANESE; WOOD-CARVING, FAR