Jazz

JAZZ is (I) a technique for the playing of any music, em bracing tricks of accent and rhythm, interpolated melodic figures, and instrumental effects; and (2) written music calling for the use of that technique or exhibiting its influence. It may have originated in a revolt of the individual ; in the insubordinate at tempt of one member of an orchestra to seize attention by star tling or amusing the listeners; but the revolt, as such, has been practically suppressed, and its mischievous and humorous tra dition, in many quarters, forgotten.

The rhythmical foundation of jazz is ragtime, which displays a syncopated air, brought into sharp relief by a regular beat, in common time, in the bass. Ragtime has long been characteristic of the religious and secular folk music of the American negro. In the first decade of the 2oth century ragtime became the American popular idiom, and was used with increasing fluency and variety. Jazz represents, in one respect, a continuation of this development of and preoccupation with rhythm. One of its prin cipal novelties, consisting of abnormalities of accent, would prob ably have come independently of jazz bands.

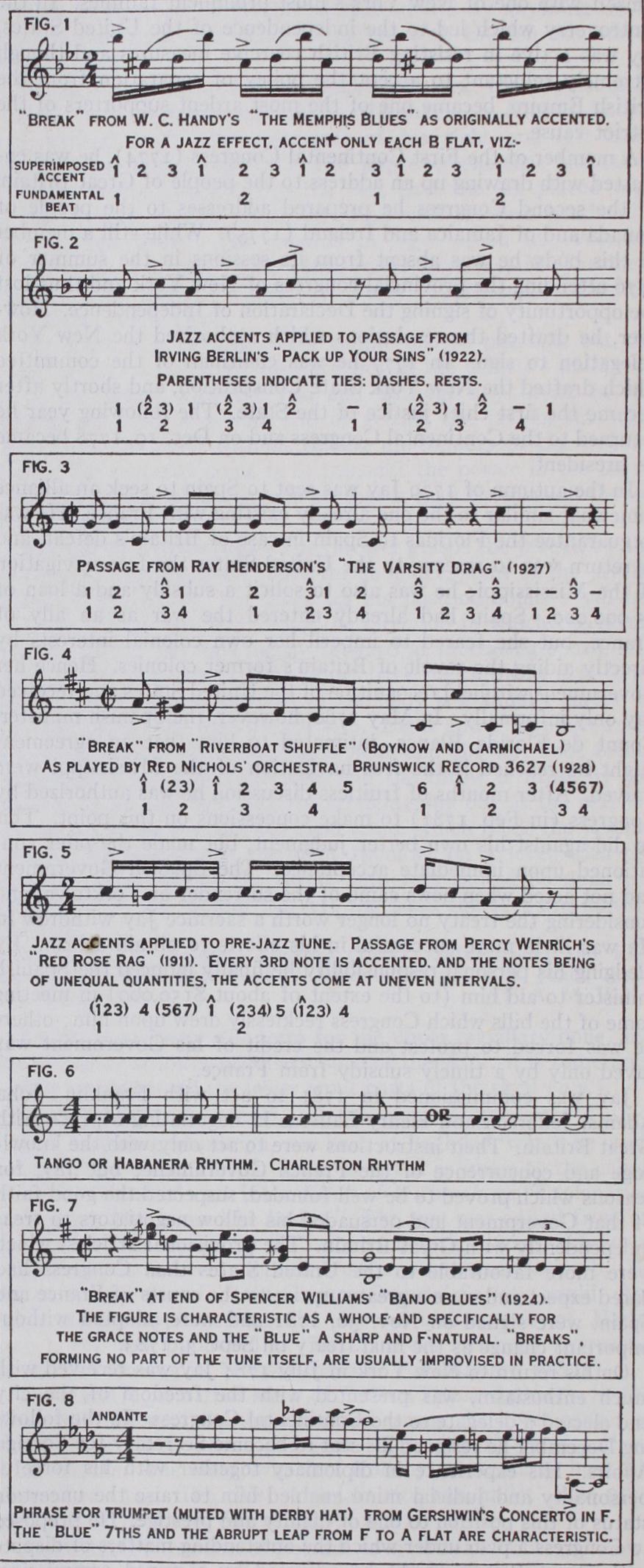

The commonest of these abnormalities is accenting the offbeat; thus, in 4-4 time, stressing the 2nd and 4th beat in each measure instead of the 1st and 3rd. Almost as common is the device of superimposing a 1, 2, 3 rhythm upon the fundamental 1, 2 or I, 2, 3, 4 of the dance; i.e., a brief melodic passage is conceived of as divided into consecutive groups of three notes of equal value and is accented accordingly, giving a momentary effect of triple time; obviously, a jazz effect may also be obtained by so accenting beats or equal fractions thereof as to group them in fives, sevens, etc. ; or the intervals between accents may be unequal (figs. 1-5).

The effect of jazz accents is complicated by skipping or tying notes (figs. 2, 3, 4), skipping or anticipating beats, etc. "Licks" (unexpected accents interpolated by single instruments) are sprinkled here and there. Patterns are formed by silence through a given part of each of several successive bars ("stop time").

The rhythm instruments have various patterns of their own which may be independent of the jazz accents in the melody. The famous "Charleston" rhythm, common in old spirituals as in jazz, was based on a skipped beat, and arrived at by taking the tango rhythm (a dotted quarter, an eighth and two quarter-notes), and striking only the dotted quarter and the eighth-note (fig. 6). The fashion in jazz rhythms and accents constantly changes; with familiarity, each is successively discarded as "corn-fed".

Jazz in its aspect of instrumental effects and tone colours was incubating before and during the ragtime period. Negro musicians in the 19th century unquestionably played cornets into buckets, boxes and derby hats, filed down the mouthpieces to raise their range, scratched a washboard or a mule's jaw-bone to mark rhythms, played tunes by blowing into the mouths of jugs or lengths of gas-pipe, as to-day. But their experiments were in general sporadic, individual and above all, covert. In jazz they are open, and the visual effect of comic instruments, as of the bodily contortions of the musicians, is, though dispensable, a part of jazz itself. But before the official appearance of jazz, New Orleans, if not other places, had genuine negro jazz bands, obscure and illiterate, but playing a violent form of this music, chiefly marked by a polyphony of strange tone-colours and instrumental effects. Experimentation for novel colours and effects has always been characteristic of jazz orchestras. It has eliminated the strings or retired them to the background in favour of saxophones, clarinets, brasses and banjoes; has extended the upper range of clarinet, trumpet and trombone ; perfected a legato technique for trombone and tuba ; developed the banjo into a resounding rhythm instrument, the tenor banjo; discovered various effects pos sible to wind instruments without mechanical aid, such as the guttural flutter-tonguing, the explosive stop-tonguing ; and per fected many unfamiliar and effective mutes for the brasses, all with the object at first of surprise and amusement simply, but later, of beauty or volume as well.

If the coming into existence of jazz bands was due to any single stimulus rather than simple evolution, the most plausible stimulus was the rise of the negro blues (q.v.) and their exploitation by W. C. Handy. The blues are a highly distinctive form of Afro American secular folk song, which became popular among lower class Southern negroes before 19ro ; they are at once melancholy and humorous, and deal exclusively with the singer's own emo tions and philosophy. Their chief peculiarities are a three-line stanza, a melody of only 12 measures, in common time, and the fact that between the last syllable of a line, as sung, and the first syllable of the next, there generally occurs a space through which the voice is silent and which is filled in with improvised figures (a "break") on the accompanying instrument. Handy, a negro orchestra-leader in Memphis, Tenn., in 1910 composed a dance in the blues pattern and in 1912, when it had attracted wide atten tion, published it as "The Memphis Blues." In playing this, the first published blues, one musician after another of the Handy "band" (strings, clarinet, trombone, saxophone, piano and drum) would take the "break" in the third section (fig. I) solo, and strive to outdo the others; on repetitions, moreover, a soloist would improvise a whole chorus while the rest marked the time and the original harmonic changes; a procedure similar to that of the modern "hot chorus." "The Memphis Blues" contained, besides its breaks, another important peculiarity: the frequent flatting of the seventh and third notes in the scale, in a melody whose pre vailing mode was major, by which Handy had intended to sug gest characteristic slurs of the untrained negro voice. These harsh

and mournful sounds are a principal melodic characteristic of jazz, and whether or not they are slurred, or sounded as part of the favourite discord of the minor second, they are known as "blue notes." They abound in the nervous, angular figures of the "breaks" and "hot choruses," in the blues-type of piano jazz (all crashes and chirps) which cannot be analysed here, while jazz tunes are frequently rounded off by a brief coda ending on the flat seventh or the chord of the ninth. While the blues pattern itself has not been adopted by white composers, the "breaks," "hot choruses" and "blue notes" are of the essence of jazz, while the spirit of competition aroused by the breaks may well have been the original incentive to determined experimentation in search of surprising and humorous effects. Finally, the humour of the best modern jazz inherits the rueful or bitter flavour of the blues.

By 1915 there were white bands in New Orleans, with jazz instruments, and playing what was first known as jazz : polyphony in the sense that while the rhythm and harmonic scheme of some given song were referred to, each man otherwise played, as pierc ingly as he could (in competition with his fellows), whatever he pleased. Late that year one Joseph K. Gorham discovered and brought to Chicago one of these bands (clarinet, cornet, trom bone, drum and piano), which there achieved fame as "Brown's Band from Dixieland." Bert Kelly, another manager, in the same winter bestowed the name "jazz bands" upon his numerous Chi cago orchestras; and in the spring of 1916 imported a second white New Orleans organization (clarinet, banjo, saxophone, drum and piano). (Kelly was doubtless familiar with one or both of the previous uses of the word "jazz": as a disreputable verb, and, in New Orleans, as a verb applied to music and meaning "to speed up." No more fanciful derivations are worth considering.) In 1916 Brown's Band invaded New York; in 1917 the Dixieland Jazz Band (white, and from New Orleans) spread jazz to the winds with its phonograph record of D. J. La Rocca's "Livery Stable Blues," and Jim Europe (coloured) as an A.E.F. band master introduced it to Europe.

The inevitable movement to modify the hideous noisiness of early jazz was led by Art Hickman, a California orchestra leader, and later taken over by Paul Whiteman, whose celebrated ar ranger, Ferdie Grofe, introduced the practice of writing elaborate orchestrations of the jazz repertoire which the musicians were required to play as written ; sacrificing spontaneity to discipline, but obtaining remarkable beauty and volume of tone. The present day "sweet" jazz, sprung from the Hickman-Whiteman reaction against cacophony, is opposed to "hot" jazz. The latter, descend ant of the Memphis ("take your turn") and New Orleans (poly phonic) schools, has modified the pandemonium of Brown's Band and renewed acquaintance with melody; but to a far greater degree than the "sweet" orchestras, keeps in mind its traditional objectives, surprise and humour. In both modern schools crystal lization has set in, and devices which once had, but have long since lost the power to startle or amuse, are now standard ; but the apparent social ambition of "sweet" leaders to achieve some sort of rapprochement with "respectable" music and symphony orchestras, impairs the prospect that the most interesting future developments of jazz will come from their quarter.

It is true that to Whiteman's suggestion (and the inspired prac tical collaboration of Grofe) is owed a remarkable experiment in the adaptability of jazz idioms to larger musical forms, George Gershwin's "Rhapsody in Blue" (1924), but the jazz of this composition is in small part "sweet." The "Rhapsody" and its composer's Piano Concerto in F (1926) demonstrated that the two primary objects of jazz can be attained by its own methods independently of the monotonous foxtrot dance-time—a condi tion to the possibility of long and yet interesting jazz compositions. To how many composers such will be possible is another ques tion. Although writers of unquestioned musicianship and some talent have made the attempt, Gershwin's success remains unique. But one major service which jazz may certainly be said to have rendered to music generally is its revelation of the possibilities of old and new instruments and mutes, and of the volume and beauty of tone and variety of colour obtainable by small orchestras.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.—The literature of jazz is confused and controversial. These are illustrative: H. 0. Osgood, So This is Jazz! (1926) ; G. Seldes, The Seven Lively Arts (1924) ; S. Spaeth, Common Sense of Music (1924) ; A. V. Frankenstein, Syncopating Saxophones (1925) ; Paul Whiteman and M. McBride, Jazz (1926) ; W. C. Handy and Abbe Niles, Blues (1926) ; D. Knowlton, "The Anatomy of Jazz," Harper's Magazine (April, 1926) ; A. Coeuroy and A. Schaeffner, Le Jazz (1926) ; Paul Bernhard, Jazz (Munich, 1927) ; and for negro rhythms see H. E. Krehbiel, Afro-American Folksongs (1914) ; N. G. J.

Ballanta, St. Helena Island Spirituals (1925) ; Practical handbooks are: Arthur Lange, Arranging for the Modern Dance Orchestra (1926) ; F. Skinner, Simplified Method for Modern Arrangement (1928). Phonograph records are listed in A. Niles, "Jazz, 1928," Bookman (N.Y., Jan. 1929). (A. Ni.)