Methods of Lifting Water by Continually Renewed Labour

METHODS OF LIFTING WATER BY CONTINUALLY RENEWED LABOUR Shadoof.—Baling up water by hand (obviously the earliest system and that by which many acres are still watered throughout the world) is slow and expensive in labour. Inventive minds soon devised mechanical aids. About the earliest must have been the contrivance made up of two upright poles with a cross-beam joining them at a point 8 ft. or 1 o ft. above ground level. Over the cross-beam (if there is no cross-beam, from the meeting point of the two poles) is slung a long tapering pole, the greater part of its length being on one side of the uprights. From the tip of the longer and slimmer portion is hung a rope ending in a skin or bucket, to the shorter end is attached a mass of clay or other weight sufficient to counterbalance the bucket when full of water, the worker pulls on the rope until the bucket dips into the well or stream; when it is filled he lets go and the counterbalance causes the bucket to rise with its water. In India this contrivance is known as the denkli or paecottah. In Egypt it is called the shadoof. Where the soil level is high above the water the lift is overcome by installing extra shadoofs, the lower one feeding the next higher and so on until the required height is attained. One shadoof can irrigate about 4 acres.

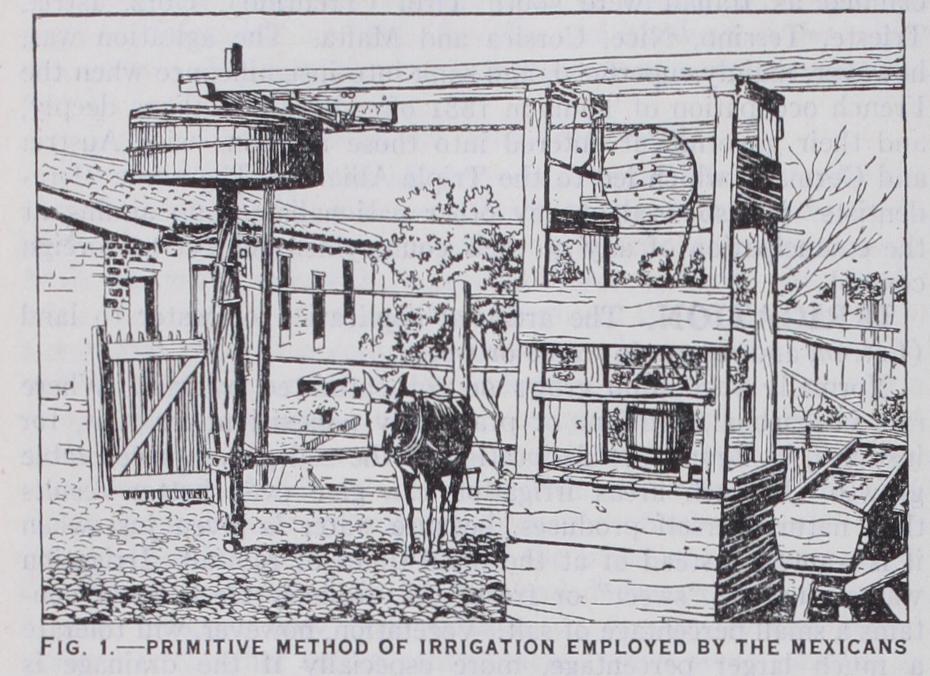

ancient aid to irrigation is the water-wheel known in Egypt as the sakia, and the harat or Persian wheel in northern India. In this instrument a beam is attached horizontally to a toothed wheel. To the outer end of the beam, cattle, usually a pair of oxen, are yoked and travel in a circular path, pulling the beam with them, thus making the wheel revolve. The latter en gages in its teeth a similar vertical wheel which thus also revolves, and in turn lifts up an endless rope to which buckets are attached at short distances apart. As the machine turns, the buckets, one by one, dip into the well in which they are hung. When the buck

ets reach the top of their course they tilt over and empty into a prepared channel leading to the fields. When empty the buckets descend again, mouth downwards for another fill. One such machine can irrigate 5 ac. to 12 ac., dependent on the height of the lift. The not unpleasing sound made by the movements of this contrivance is said to have influenced the music of the East.

Archimedes'

the most intriguing of all these anciently devised implements is the screw invented by Archimedes of Syracuse about 200 B.C. This consists of a wooden cylinder, I f t. or 2 ft. in diameter, in which there is placed a corkscrew shaped diaphragm running from end tb end. The cylinder is usually about 8 ft. to 12 f t. long, and is placed with its lower end in the water and its top lying inclined on the bank of the canal or stream, the lift usually being about 3 feet. To the centre point of the diameter of the cylinder there is a crank-handle attached, by which the whole contrivance can be revolved, the act of revolution causes the water to proceed up the internal screw and flow on to the soil. Shadoof, sakia and screw are all still in constant use.