Modern European Ironwork

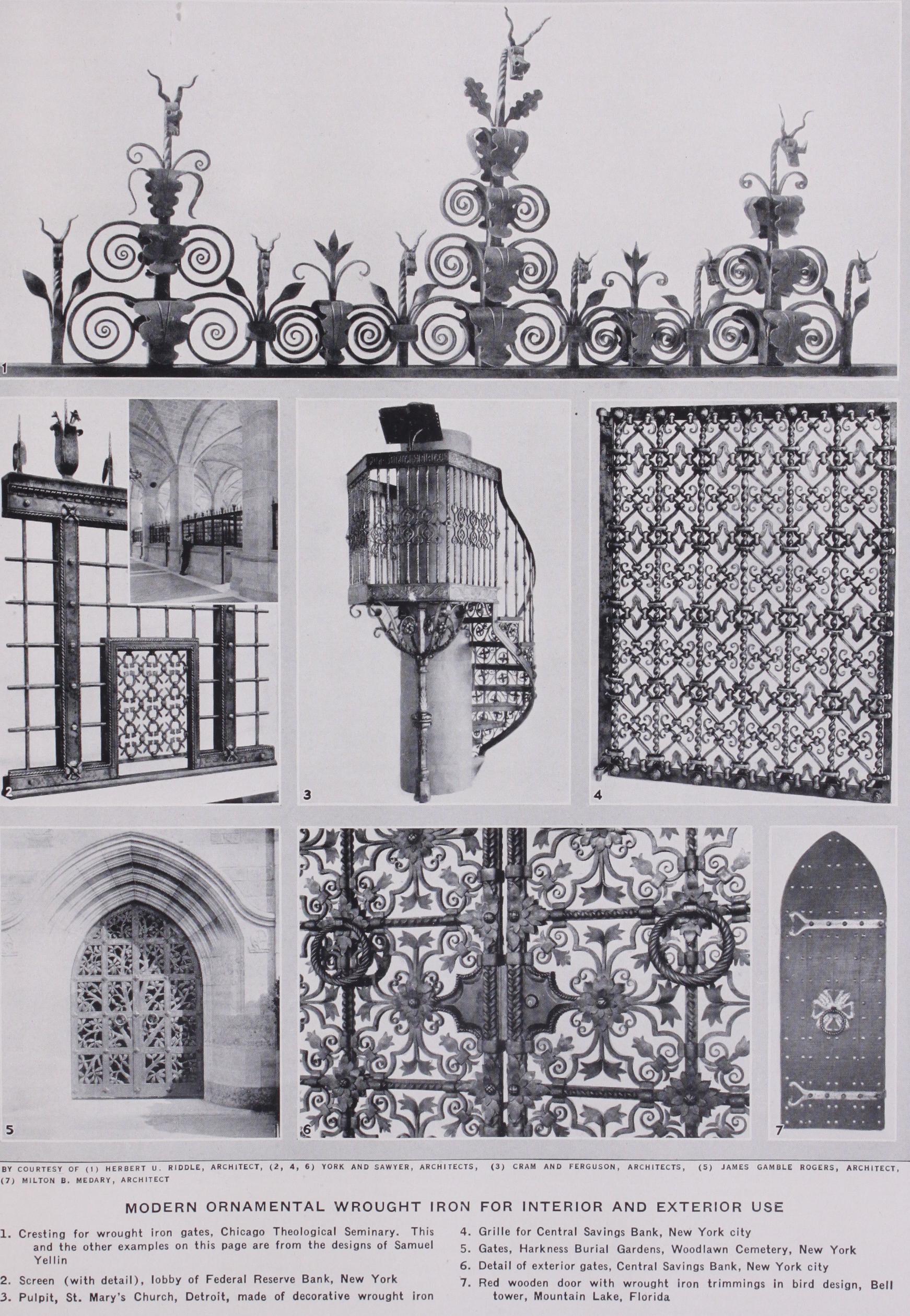

MODERN EUROPEAN IRONWORK A renaissance in the art of ironwork was achieved by the end of the 19th century. At first certain workers rediscovered this fine craft with all its strength, suppleness and complexity. The wonderful balustrade of Chantilly, a work of the Moreau brothers (188o), shows the results achieved in this respect. But this was not enough. It was necessary to return again to the underlying principles of the art in order to direct the skill of the technician toward logical achievement in the art. It was also necessary that the works so achieved should not be mere imitations of the past, but creations thoroughly of the present. It was necessary to rediscover a living style, and to this end the very conditions of artistic production had to be modified by the collaboration of workers in iron (artists and industrial workers), architects, and the public, united in a single love of this art that was being born anew. This enormous task, then imposed, has not yet been wholly accomplished. The union of art and of industry, in particular, is far from being sufficiently general ; and we shall see that this was one of Edgar Brandt's preoccupations. But the principal effort was supplied in the last years of the 19th century, and in the first years of the present century ; and it may be said that the battle, as a whole, had been won as early as 1905.

The employment of wrought iron had again been restored to common use. Architects once more employed it in all buildings of costly and elaborate construction. The public had become con scious of its elegance and its strength. New forms had appeared and the arts of metallurgy in particular had profited more happily than other arts by the researches that were then being made in the various forms of "modern style." Then, too, though the accomplishment of this period in all branches of the applied arts may very often seem questionable to-day, the underlying prin ciples followed were generally excellent; and the difference be tween the artists of the present generation and their predecessors of 189o-19o5 seems to consist especially in the fact that the more recent artists applied in a more logical manner the sound prin ciples which their elders recognized, but which they failed to observe with sufficient consistency Emile Robert supplied more than merely strong, sane doc trines ; his craft, too, was always magnificent ; his works were well-composed and clearly wrought. When Brandt and his Paris workshop made their appearance, Robert had already freed iron decoration from the invariable acanthus and adorned it with the most charming flora, varied, light and wholly fresh. He had also divested it of the confused and anomalous ornamentation which to-day is so annoying in works like the Chantilly balustrade, and he had returned to simpler structure. He had put away the file and given up metal-chasing ; he paid due regard to the hammer marks, significant proofs of the struggle by which man controls rebellious matter. (We shall find that Brandt does not share Robert's systematic aversion toward chasing.) Robert was the unchallenged prince of metal-work. He exercised considerable influence because he added to the skill of the technician and the talent of the draughtsman the intelligence of the theorist who can reason about his art.

In 1905, a State school of ironwork was established in France. It had following, it was guided by fruitful principles, it had found original forms, and achieved some masterpieces ; but it had within itself at least two elements of weakness—on the one hand (and often in Robert himself), an excessive tendency toward the fan tastic ; on the other hand, among too many artists, insufficient technical equipment.

Use of Machinery.

The modern craftsman, and Edgar Brandt probably more than others, makes use of the most perfect modern tools. His preliminary work is carried out with the pneumatic hammer, the stamper, the press. Machine-tools are employed for the assembling of parts ; the work is divided according to the rules of modern industrial organization. Each of the different workshops carries out its special task. All the parts so created around the same motif are then assembled in the welding-shop. Here modern methods again economize time and effort, while supplying work so exact that it could not have been achieved in the past. Then the different motifs go to the shop to be set up. Finally the complete work receives, in the last workshop, its definitive surface, the operatives darkening the deeper parts and brightening up the others. Some persons disapprove of this use of machinery. They fear that iron will lose "its qualities of ani mated grace and living charm." They say that it debases iron to treat it with anything but the hammer. These are the words of the editor of Bronzes d'Art Suisse and were quoted by Emile Rob ert in the first article of his review, La Ferronnerie Ancienne et Moderne, 1896. Brandt holds that these fears are entirely ex aggerated because there is no question of abandoning the forge, from which is derived to-day a part of this life, grace and charm. To Emile Robert as to Jean Lamour, the forge was no longer a means, but an end in itself, outside of which, in their opinion, no processes can be recognized. Brandt, on the contrary, takes his place at the head of the school which may be called "eclectic," because for it the forge is only one means among several others equally interesting, and is to be employed or not according to the effect to be obtained and the purpose for which the object is intended. This school may also be called the "modern" school because it frankly adopts for its means the processes supplied by present-day science.

It is, then, of new effects that we must now speak. Brandt, for example, succeeds in decorating large frameworks with orna ments which support one another by their borders, without the aid of bars. Bars would formerly have been necessary to strengthen screens of this kind and, therefore, would have modified the character of the whole by dividing it into a large number of small sections. Acetylene welding allowed Brandt rapidly to develop similar decorations of a breadth, suppleness and intricacy which literally could not be achieved in former days.

Modern technical processes open to creative activity a career hitherto unknown. As they grow more numerous, the artist's horizon is extended. His powers must increase in the same meas ure. A serious danger, that of mere facility, is now threatening. Every worker, without even a trace of genius, can use the acety lene blowpipe, can operate the stamper, or the press, and not only display a deceptive virtuosity, but achieve productions in which art has no share.

Brandt's Workshops.—Innovations in technique correspond in detail to new methods of work. In general, it is a fact that no considerable work can to-day be produced by one man alone. The various machines, the large number of orders, and their im portance make collaboration necessary. Brandt, whose beginnings were very modest, now plays the part of master of the work in his workshops; a little like the great painters, he directs some 3o draughtsmen. These different personalities add to the variety of material a variety of technique. (Brandt's principal c,llabo rator is Favier, an architect.) None among them claims an idea as his own. While successive supervision secures perfect balance in these creations, their artistic quality is constantly refreshed by manifold researches which cause the underlying formula to stand out as they are established, and which thus sustain the fire of life. The master is obliged to supply a perpetual effort of concen tration, for execution can only be achieved by obedience to the laws of unity and harmony, to the laws of architecture.

Prominent among the effective motifs which Brandt employs most frequently are pine-branches and two other motifs that seem to be his own creations. He uses them so systematically in his works and they assume so special a character that their presence alone would make us recognize their author. One is a plant of the Far East, the Gingko biloba. It is light and at the same time orna mental, lending itself with great suppleness to varied stylization, because it has along with its frail stems, tendrils and leaves, small fans which make a dark spot among the delicate lines. Secondly, and especially since the World War, Brandt shows a fondness for the decoration of vertical planes by a system of circles and scrolls.

But Brandt's originality lies less in the elements he employs than in the uses he makes of them. The variety of motifs, the mingling of a naturalistic flora with stylized flowers, his freedom of interpretation are so many characteristics common to Brandt's art and that of the generation of 189o-19o5. In Brandt, too, are to be found the combinations of lines to which modern style has accustomed the eye, notably the metal rods, delicately sinuous, which suddenly curve back at very sharp angles. In turning over the pages of the art reviews of the first decade of the present century, we see Brandt's work, from his first attempts, integrating itself in a very normal manner with the productions of this period. This affiliation with his era does not, however, render less striking the fact that Brandt brought forth a new method of composition as harmonious as that of his predecessors was full of contrasts.

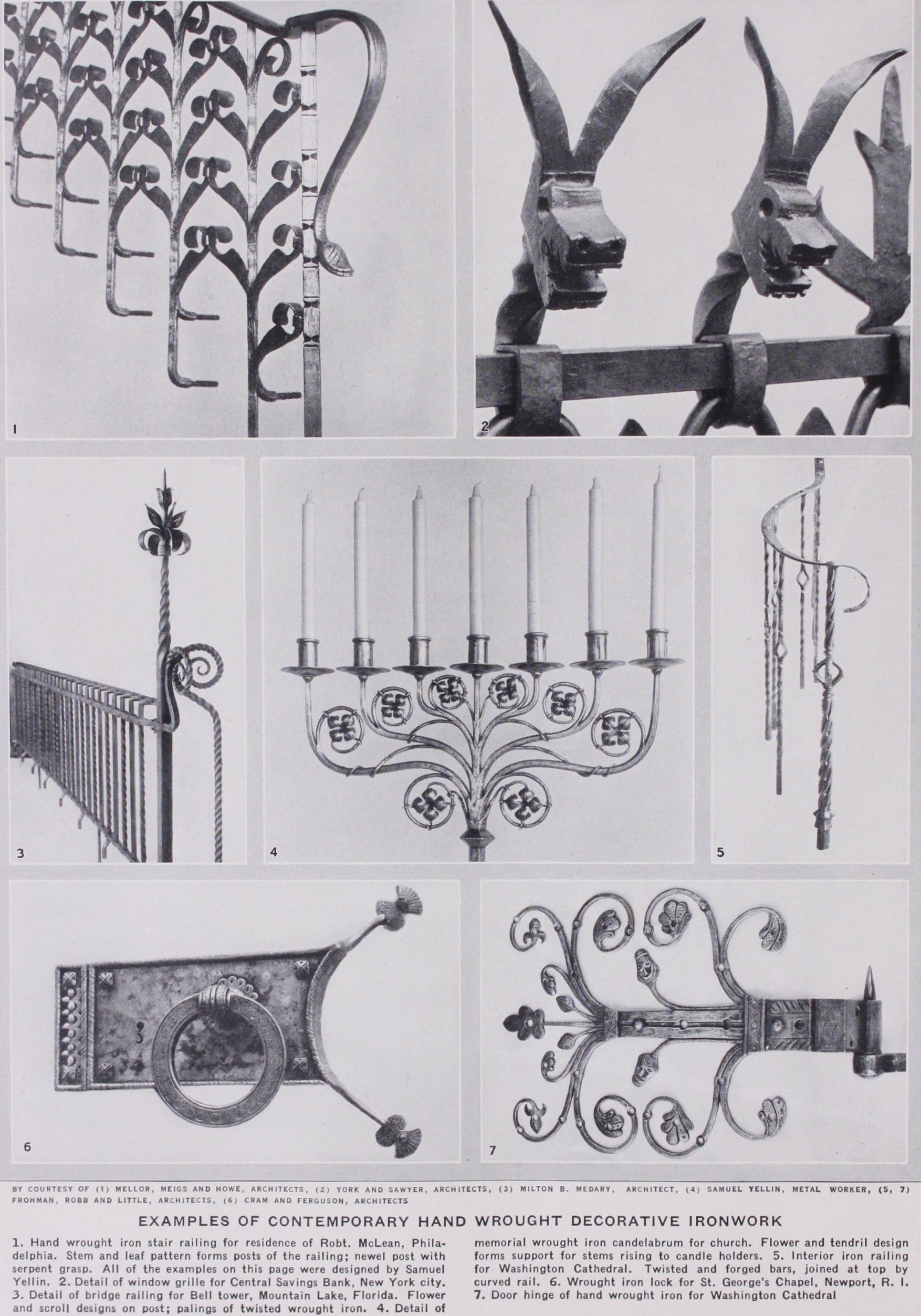

(R. RE.) The interest and charm which the most unpractised observer must find in the work of the early craftsmen in iron is due to the fact that the metal was worked at a red or white heat. There was no time for measuring or copying a design save by the eye. Thus we get a spontaneity and a virility in forged work which expresses the life of the metal and gives the work its unexpected charm. These old craftsmen knew every branch of their work; they lavished as much skill and creative ability on a small handle as upon a great gate. No detail was overlooked, no matter how small or insignificant. This can be seen in various examples of their works, as in the fine old chests and boxes ; the wonderful old locks, keys and other decorative hardware used in the great cathedrals. Thp sincere nature of craftsmanship and the proper use of materials for ends to which they are well adapted is little understood to-day. This is not because there is any lack of in formation on the subject, but because the perfection of the mechanical means of production at our disposal has blinded many to the simplicity of the means which produced the great works of the past.

Nevertheless there is more interest shown in arts and crafts to-day and more of a trend towards the use of them than ever before. Along with the good work comparable to that of the old masters, however, there is also a profusion of bad work. This bad work includes all the work which is tritely inventive and not truly creative. It is work done in an artificial manner; work which has no tradition, and is designed by those who do not understand the possibilities and limitations of the material in which they work. These people do not possess the true crafts man's training, and so the work is done in a mechanical way. Iron is sometimes of necessity artificially welded because of de signs which are not properly conceived. The new ideas and new designs being introduced for this great craft are dangerous, for no work is good unless the material is used in the way it should be, and the designs made to suit that material.

Iron not only suggests security, strength, defence and durabil ity, but lends itself to many beautiful and useful as well as ornamental purposes. But to-day these uses are being abused and ironwork is used promiscuously by those who try to establish a vogue in this craft. Much of the ironwork found on public buildings and in homes is for cheap show only, and little thought is given to the practical or decorative value of the work. A shop window may have a delicate grille or an ornamental gate, neither of which has any practical use whatsoever. It is conspicuously placed so as to attract the attention of the passer-by ; the iron work does not play into its architecture and is not in harmony with its surroundings.

There are certain fundamental principles of design and execu tion to be expected in all good ironwork, and the craftsman who is trained as a designer as well as a metal worker knows every one of these. Furthermore, works of the old masters should ever be before the student of this craft, and examples in museums and documents in libraries should help him in securing the true kind of inspiration.

Although a metal worker is able to furnish drawings suggestive of the style, scale, proportion and general lay-out of the design, his real study of details can only be accomplished on the anvil. It is this actual study in the metal which gives the work its un expectedness and charm, and this can only come from a deep knowledge and love of the material. The making of beautiful ironwork cannot be fully described and illustrated on paper; it is often necessary for the craftsman to make sketches in iron, that is, make pieces in the actual material, before he illustrates on paper.

Although iron is the least expensive of all metals, there is no material which lends itself to more beautiful treatment. Neither is there a material which can be worked more quickly. It is one of the simplest and most direct, therefore one of the most difficult mediums in which to work. Very often the craftsman to-day is asked to slur over work which does not seem important, or which will not show, and is urged to make his work as cheap and showy as possible. Again, when a metal worker has a certain appropria tion to meet for the work he is doing, he will carry out the de sign in the cheapest possible way in order to meet this appropria tion. Instead, the craftsman should simplify the designs to meet the allowance given, in order to make the work in the best pos sible manner.

Materials should not be taken from their proper spheres and used by tricks and illusions in other spheres. For instance, there are workers in iron who attempt to make this metal look like wood, gold or bronze. They finish it and work it so that it tricks the observer, distorting one material into the semblance of an other, thereby losing both its simplicity and significance. Some times colour is used on metal work. A decorator often wishes to carry his colour scheme into lighting fixtures or other metal work, but although occasionally a little gilt may be used to give warmth to a piece of work, the colour should not be used with the idea of concealing bad workmanship. The most logical way to give colour to ironwork is to incorporate another metal, such as brass of a golden colour, applied or inlaid. Colour is also used as a background for ironwork. This is especially done in cases of pierced work or when the motif is of an open design. The iron work is then backed with some material, such as an old red velvet. This may also be done in cases of mounting ironwork on wood work, where the woodwork is stained so as to make a suitable background for the ironwork. (S. Y.) In casting decorative ironwork it is first necessary to adapt or conform the ornament to suit this class of work, then to prepare the patterns for the moulder. The production of the work now becomes a mechanical repetition, and whether the castings from each pattern be few or many, the results will always be an invariable sameness.

Wrought iron contains less carbon, is not as brittle and can be hammered or cut freely. Wherever this iron is worked by hand it is impossible to get an exact sameness or repetition, which in all cases creates a natural interest of variation in design.

Technique of Hammered Ironwork.

Hammered ironwork, the term commonly used, is often misunderstood by designers who are not familiar with this craft, and instead of a natural hand-wrought texture, the iron is defaced in a very unnatural manner. For instance, a man will place a section of rather smooth iron on an anvil and begin to disfigure it with uneven hammer blows, intending to make hammered iron. The designer, in this case, does not understand the proper use of the material.

This might be well illustrated in the case of a design composed of horizontal or perpendicular members of one-inch round iron. There should be no attempt to take a one-inch round section and abuse it as described, but instead a one-inch square section should be used, forging it as near to round as the human eye can measure. The bar will then possess the quality of hand craftsmanship and be far superior in character to any disfigured work or, on the other hand, to any machine-like perfection.

Execution of

Work.—First, draw a sketch to a small scale, so as to obtain the general composition, proportion, silhouette and harmony with the design of surrounding materials or conditions. This sketch should then be developed into full size to obtain details of ornament, various sections and sizes of material, and a general idea of the method of making. At this time, careful consideration must be given to the practical use of the piece of work so that it may serve its purpose in the best manner pos sible. Workers in iron should always attempt to make everything direct from a drawing, rather than from models. When working from a model, the object becomes more or less a reproduction, whereas the drawings allow a greater opportunity to express the craftsman's individuality.

Studies or experiments in the actual material are now made, for here many things are revealed which could not possibly be shown on paper. The character of a twisted member or the flexibility of the material might be used for example to show how difficult it would be to conceive many such things in the drawings. For this reason the true craftsman should often make a fragment or portion of the ornament in the actual material first, and make the drawings later.

Tools Used.

Methods of working and the tools used to-day differ very little from those of early times. Machinery can some times be used for the greater convenience of the craftsman while working, thereby increasing his efficiency and permitting a great deal more work to be accomplished, yet it cannot be used in the actual making of any piece of work where the character of the craftsman is to be expressed. In comparing a forge of early times with one of the kind used to-day, a very good illustration of the valuable use of machinery can be shown. The purpose of the forge is to heat the iron to such a temperature as to make it flexible while working. The intense heat required cannot be obtained from the draught of an ordinary burning fire; therefore air must be blown to increase the draught. Fig. 1, a forge of mediaeval times, shows air being blown through a fire by a large bellows which must be operated by hand or foot constantly, to keep the draught flowing. Fig. 2 shows one of the types of forges used to-day. A machine blows the air into the fire, thus saving much labour and loss of time, which can be applied to better pur poses.

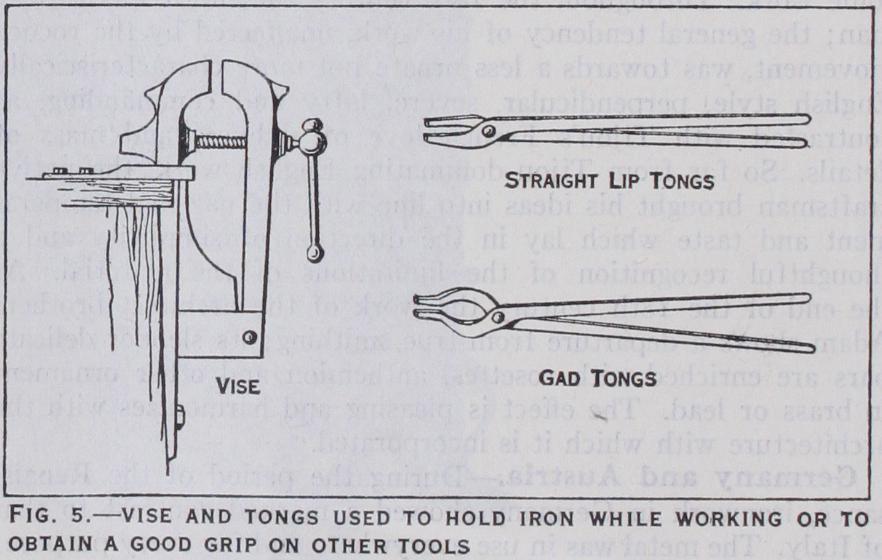

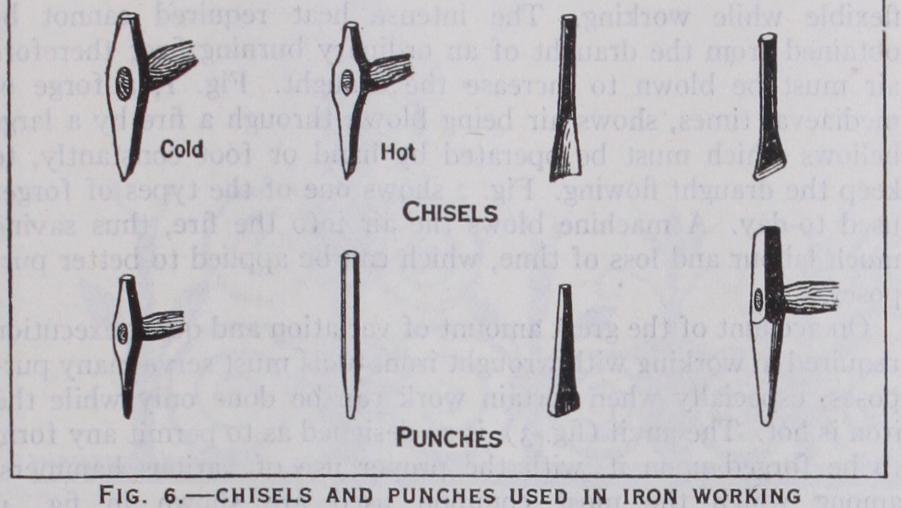

On account of the great amount of variation and quick execution required in working with wrought iron, tools must serve many pur poses, especially when certain work can be done only while the iron is hot. The anvil (fig. 3), is so designed as to permit any form to be forged upon it, with the proper use of various hammers, among which the most common used are shown in fig. 4. Wherever a strong grip is required to hold a tool or some smaller fragment of iron while working, the vice and different shaped tongs are used, as in fig. 5. There are also many kinds of chisels and punches, among which the most common are illustrated, and quite often it is necessary for the craftsman to make special tools for special occasions. Fig. 6 shows a few of these.

Iron in the Working.

Considering the broad scope of metal work, it is easily seen that many processes occur in the working. A fine piece of ornament upon a Gothic box-lock must be treated far differently from the cresting over a large set of Gothic gates. The craftsman must feel the spirit of any design and use the correct sections of the material. In a gate or grille, for example, the frame or main members must be square or rectangular in section, whereas the ornamental members may be diagonal or round.

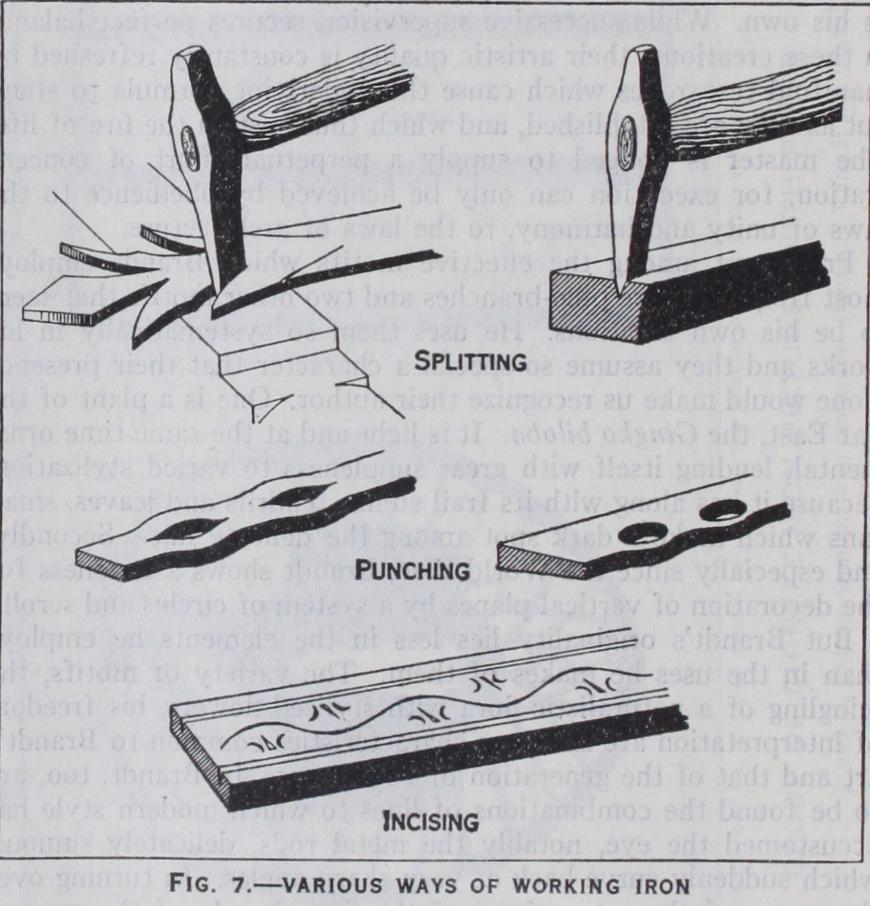

The various methods familiar to the craftsman in working are forging, splitting and punching, incising, repousee, carving, pierced work, spinning and stamping, welding, riveting, the use of collars or bands, and the different ways of finishing the material. The most fascinating work in metal is at the forge, where one who possesses the ability can produce work in iron with a spontaneity that cannot be obtained in any other way. Besides the making of scrolls, or various forms of open design, the greatest interest is due to the metal being so pliable. For an example, in splitting or incising the conventional decorative floral motif, the chisel natur ally changes the section as it digs into the iron. This is also true when various punches are used, fer as can be seen by the illustra tions the iron will take another form, but the material or metal is never quite lost—unless it is severed entirely. The implements for splitting, punching and incis ing are shown in fig. 7.

Repousse work applies to thin metal where the material is raised from the back or under side to the greatest depth or height re quired, and then modelled by the use of various tools and hammers to its required form. Wherever the repousse ornament is not very high, or requires little model ling, the work can be done with tools of various shapes, with a block of lead (fig. 8) used as a base, while hammering. If the de sign contains a great deal of modelling, as in a mask, after the metal has been raised to its greatest height from the back, lead is poured in to fill and act as a foundation. A margin of metal is bent around the lead so as to keep it in position, and the model ling or shaping of the face is done on the outside surface, follow ing a fine outline scratched on the iron to act as a guide.

Incised and carved methods are used where a surface of metal requires certain decorations or designs. Of the two, carved metal requires the greater care, as it should be used only for small, fine details, and must be done in a suggestive way to preserve the metallic feeling, rather than as if copied from a sculptured model.

Another method of decoration is to pierce or cut certain designs or forms out of the thin metal so that either a coloured back ground or natural light will show the silhouette in the ornament. Many beautiful forms can be used to advantage in this kind of work. It is also correct to stamp certain objects in thin metal, providing the design is made for this purpose This is usually done where a great quantity of the required design is needed, thus making a die for the exact form. By placing the die on the metal and striking it the required stamping is made. Very often the stamped object is worked over by hand to give it a hand wrought appearance, but this is not correct and is never done by the true craftsman.

Many beautiful forms and shapes are obtained by spinning various metals. For example, a sphere or ball, which is meant to be perfectly smooth and true, can be very easily spun in two halves and then assembled. This is much more practical than attempting to hammer or beat the metal by hand.

The foremost methods of fastening or tying one fragment of iron to another are welding, riveting and the use of collars or bands of various forms. As can be seen by the illustrations of these methods, each one has a different effect upon the design; therefore each must be used in its proper place. In the case of welding, the desired forms are forged from a long piece of iron, and then, as in the case of a ring, the two ends are merged to gether as one. Another example of welding, which shows the great variety in this process, is that of a number of pieces of iron being welded together rather than split from one piece of metal. An illustration of welding, riveting and the use of collars or bands is shown in fig. 9.

Finish.—Without the correct finish the full beauty of metal work cannot be appreciated. Iron, like any other material, must be finished in accordance with its use or purpose, and must also receive a certain amount of care at various times. Interior iron work should possess the natural finish, which is of armour colour, and the metal can be polished as bright as silver. After the cor rect lustre is obtained, an oil or wax is applied; then, in the course of time, the object receives a very beautiful patina. In the case of exterior work, the iron should be only slightly polished and left more with the natural colour obtained from the forge.