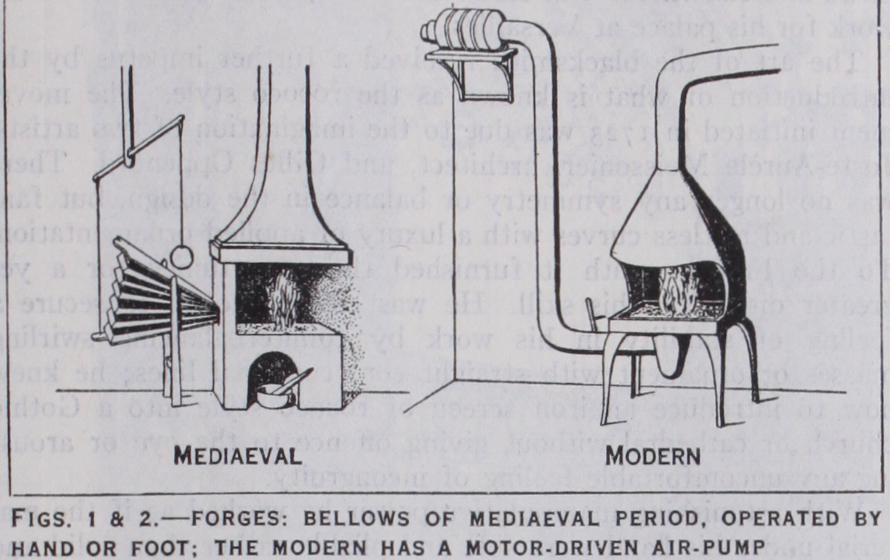

The Mediaeval Period

THE MEDIAEVAL PERIOD the Loth century iron-working among the English was as fully developed as at any time during the next three centuries. It appealed to the sturdy English temperament as a difficult material calling for swift action ; it suggested strength, stability and protection, all of which qualities were in those days not to be ignored. Its first use was purely protective; enemy attacks were frequent, and doors had to be strengthened with massive iron-work inside and out. Window openings, espe cially those of the treasuries of mansions and cathedrals, were filled with strong interlacing bars of solid iron; a good example remains at Canterbury cathedral. When in course of time the need passed away, there came greater freedom of work and a definite intention of ornament. Throughout England, church doors are found with iron hinges, the bands worked in rich ornamental designs of scroll-work, many of them probably the work of local smiths. They vary from the plain hinge-band with crescent to the most elaborate filling of the door. Examples exist at Skipwith and Stillingfleet in Yorkshire, many in the Eastern counties and others in Gloucester, Somerset and the west Midlands. The next movement came with the erection of the great cathedrals and churches, whose shrines and treasures demanded protection. Winchester cathedral possesses the re mains of one screen with a symmetrical arrangement of scroll work. The grille above the tomb of Queen Eleanor at West minster Abbey recalls the maker Thomas de Leghtone, a master craf tsman in iron who had succeeded another great smith, Henry of Lewes. Tombs were enclosed within railings of vertical bars with ornamental finials at intervals, such as that of the Black Prince at Canterbury. A third development appeared ;n the early years of the 14th century when the smith, working in cold iron, attempted to reproduce Gothic stone tracery in metal. This work was more like that of a joiner than of a smith, being often in small pieces chiselled and riveted, and fixed on a background of sheet-iron. A typical example is in Henry V.'s chantry at Westminster Abbey ; but the most magnificent is the great grille at St. George's chapel, Windsor, made to protect the tomb of Edward IV. For many years it passed as the work of the Fleming, Quentin Matsys, but it is now known to have been executed by an Englishman, John Tresilian. Many small objects such as door-knockers, handles and escutcheons are to be found executed in the same manner. Smithing declined in England during the i6th century.

France.

In door-hinge ornaments France followed much the same line as England, and beautiful work is found on church doors, especially in central and northern France. It reaches a height of greater elaboration and magnificence than in Eng land, the culminating point being seen on the west doors of Notre Dame, Paris, the ironwork of which is so wonderful that it was attributed to superhuman agency. Grilles at Troyes and Rouen reveal a high standard of excellence, but tomb-rails found no favour. What we have called "joiner's" work was immensely popular; it was applied to small objects such as door handles, knockers, ambry doors, and above all to locks, which exhibit an amazing amount of detail and a delicacy of finish such as could only come from a French craftsman. France has succeeded in preserving more of its mediaeval work than England.

Germany.

In Germany the door-hinges present greater stiff ness than those of France. Examples exist at Nuremberg, Mag deburg and elsewhere; unusually fine locks and other objects in Gothic architectural style are common enough. Rich pierced work is also found and hammered work of an heraldic character, but the German smith of the period had not the same under standing of Gothic work as his French neighbour.

Belgium.

Belgium made a late start in the working of iron, but the number of objects still existing such as candelabra, fontcranes, lecterns and gable crosses, show an extended appli cation and thorough knowledge of the art. The iron well-cover by the cathedral at Antwerp which dates from 147o enjoys a wide reputation. The Matsys family of Louvain were celebrated smiths.

Spain and Italy.

Spain followed much the same lines, the craftsmen imparting to their work the characteristic richness and elaboration of their Gothic architecture. Italy seemed hardly at home with iron, and was content to adopt the easiest methods of workmanship. The screen of the Scaliger monuments at Verona, a grille at Santa Croce, Florence, and another at Siena, give an Italian rendering of Gothic tracery with panels of pierced sheet-iron.

The end of the mediaeval period in Europe found the smith departing from legitimate design in his work and indulging in methods hardly appropriate to his material; attractive as the result is, it does not satisfy our sense of what work in iron should be, nor did it serve to bring out the power of the craftsman.

Italy.

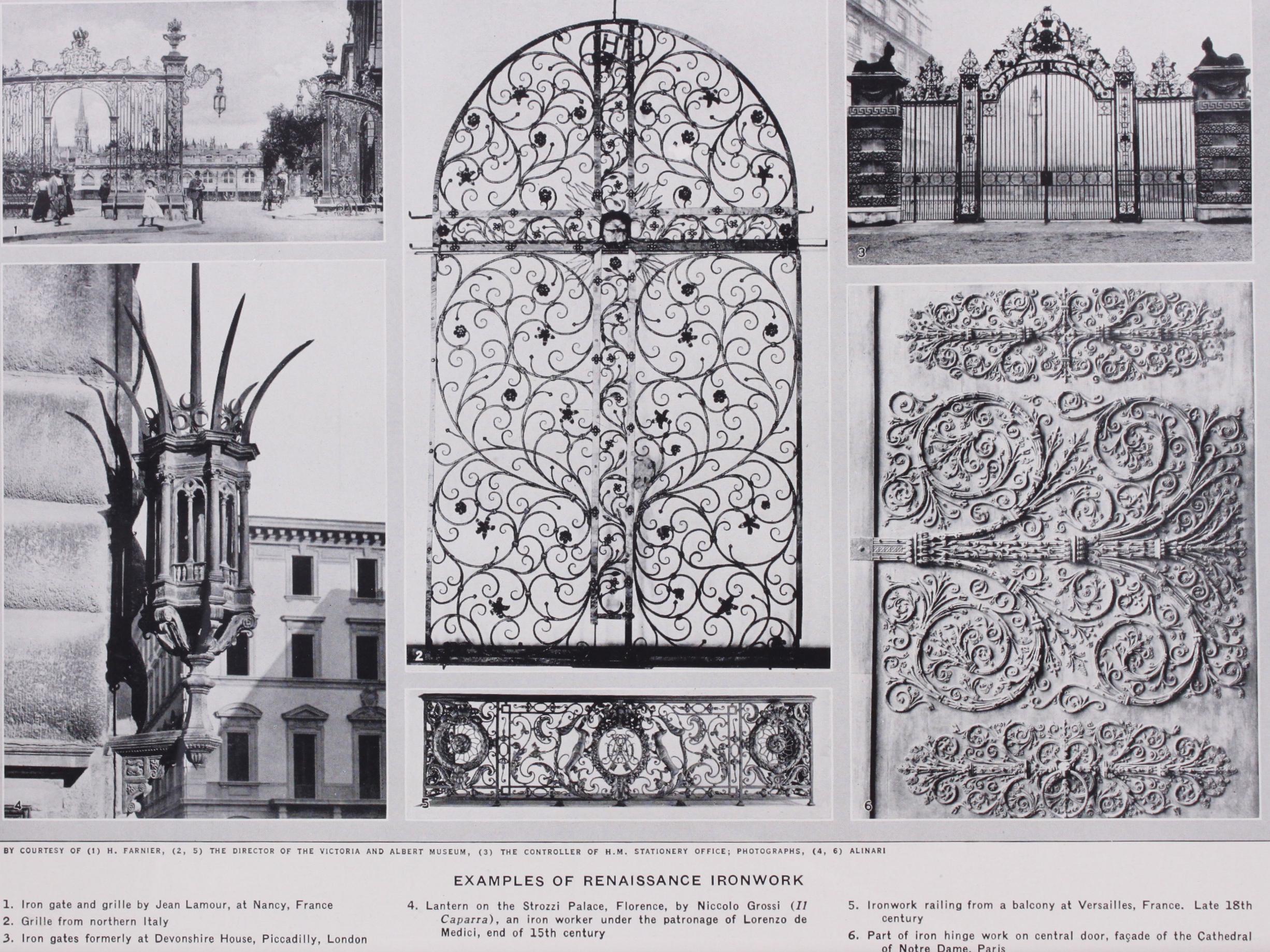

It might have been thought that in the home of the Renaissance, ironwork would have proceeded at the same pace and with the same brilliant success as architecture, sculpture, bronze-casting and the other arts. Strangely enough, little use of it is found in connection with the fine buildings of the revival. Bronze was favoured, and what in other countries is found in iron has its counterpart in Italy in bronze. The manual labour in volved in the use of iron did not commend itself to the Italian temperament, and as time went on the smiths grew less in clined for the more difficult processes of hammering and weld ing, and contented themselves ultimately with thin riband iron, the various parts of which were fastened together by collars. Work of the later periods may be distinguished, apart from the design, by this feature, whereas the English and French smiths vigorously faced the hardest methods of work, and the German and Spanish smiths invented difficulties for the sheer pleasure of overcoming them. Notable centres of artistic ironwork were Florence, Siena, Vicenza, Venice, Lucca and Rome, where im portant pieces may be found in the form of gates, balconies, screens, fan-lights, well-covers and a mass of objects for domes tic use such as bowl-stands, brackets and candlesticks.

In screen-work the favourite motif was the quatrefoil which is found with many variations over a long period of time. Early examples are strong and virile, later ones tend to weakness. The C-shaped scroll is used in many combinations. The churches and palaces of Venice contain many examples. Peculiar to Italy are the lanterns and banner-holders such as may still be seen at Florence, Siena and elsewhere, and the rare gondola-prows of Venice. Of the ironworkers of the early Renaissance the most famous was Niccoto Grosso of Florence, nicknamed 11 Caparra be cause he gave no credit but insisted on money on account, who worked at the end of the 15th century. Vasari thus eulogizes him : "He was truly unique in his craft, and has never had and never will have an equal." From his hand is the well-known lantern on the Strozzi palace in Florence, repeated with varia tions elsewhere in the same city. Siena can show other lanterns and banner-holders attached to the facades of its palaces. Cres sets are still to be seen at Lucca and a few other towns. The Victoria and Albert museum, London, contains two gondola-prows in fine pierced iron. Through the i6th and 17th centuries Rome produced much good work of a more virile character than that at Venice, and the same may be said of other cities. To the in fluence of the Rococo movement reference will be made later.

Spain.

Here the work of the Renaissance period reached a height of grandeur and magnificence attained in no other country. Of all the Spanish craftsmen the smith and the armourer were the busiest, especially during the i6th century. The particular manifestation of work in iron which for more than a century towered above all the others may be seen in the screens of monu mental size (rejas) to be found in all the great cathedrals of Spain. These immense structures rising to 25 or 3o ft. show sev eral tiers of balusters divided vertically by columns of hammered work and horizontally by friezes of hammered arabesque orna ment, and are surmounted by a cresting which is sometimes of simple ornament, but more often a very elaborate design into which are introduced a large number of human figures; shields of arms are freely incorporated, and the use of bright colour and gilding adds to their impressive beauty. The great balusters are always forged from the solid, and their presence in hundreds and possibly thousands demonstrates the extraordinary skill and power of the Spanish smith. The reja shut off the high altar of the church or cathedral, and a further opportunity came to the smith when the choir was moved westward. This necessitated a second screen to enclose the east end of the choir, and naturally this screen must be in no way inferior to that of the high altar. Thus in many cathedrals two of these monumental rejas are found facing one another. It was the smith's opportunity, and he availed himself of it to the full. His work may be seen in all the large cities of Spain—Barcelona, Saragossa, Toledo, Seville, Burgos, Granada, Cordova and many others. The screens fol low the same lines of general design, but the balusters are some times of twisted iron and occasionally, as in the royal chapel at Granada, they are opened out some feet above the base into various devices—a method reminiscent of an earlier period. Similar work but on a smaller scale is found in gates, balconies and window-screens ; wrought-iron pulpits also exist. The panels of hammered and pierced iron heightened with colours and gild ing were used in connection with domestic architecture, and a note must be made of the fine nail-heads which ornamented many doors.

France.—The Gothic tradition survived in France until well into the 16th century, and was marked by the production of work of the highest skill largely in the form of locks, knockers and caskets of chiselled iron. The introduction of the Renaissance style made no great difference to the direction of the smith's art—a strange fact when it is remembered how Germany and Spain were fabricating works of enormous size and magnificence in wrought-iron. France, like England at that time, was content to make door furniture, in the form of locks, keys, bolts, es cutcheons and the like, but did little work of any great size. A school of locksmiths came into being under Francis I. and Henry II., working from designs by Androuet du Cerceau in the Oth century and Mathurin Jousse and Antoine Jacquard in the i7th. The bows and wards of keys were of unusually intricate design, and the locks of corresponding richness. Representative pieces may be seen at the Victoria and Albert museum, London, among them the famous Strozzi key said to have been made for the apartments of Henry III., the bow of which takes the favoured form of two grotesque figures back to back. But as far as architectural ironwork was concerned, France remained almost at a standstill until the accession of Louis XIII. in 161o. Under that monarch, a worker at the forge himself, there came a great revival. It seemed to be unin fluenced from without, at first weak, as if feeling its way, but by the end of the 17th century it had attained a marvellous pitch of perfection. It proved to be the beginning of a new move ment, the force of which made itself felt in the adjoining coun tries and inspired the workers with new energy which unfortu nately at times dwindled into mere imitativeness. From the accession of Louis XIV. the French ironworkers must be acknowledged as the cleverest in Europe, combining as they did good and fitting design with masterly execution. Their designs were often very daring, reach ing the limit of what was allowable in such a metal as iron. They recognized its great adaptability and took every advantage of it, at the same time being conscious of its limitations. Their oppor tunities were endless. Screens and gates were needed for parks, gardens and avenues, staircases for mansions and palaces, screens for churches and cathedrals. Among celebrated designers were Jean Lepautre, Daniel Marot and Jean &rain. The earlier work is of a simple character, balconies for instance being in the form of a succession of balusters, but as the smith became more conscious of his powers they took the form of panels of flowing curved scrolls rendered with a freedom never attained before, while constructive strength was observed and symmetry main tained. Enrichments were usually attached in hammered sheet iron. These may be considered the distinguishing features of Louis XIV. work such as that at St. Cloud, Chantilly, Fontaine bleau and elsewhere. But Louis XIV. surpassed all efforts in the

work for his palace at Versailles.

The art of the blacksmith received a further impetus by the introduction of what is known as the rococo style. The move ment initiated in 1723 was due to the imagination of two artists, Juste-Aurele Meissonier, architect, and Gilles Oppenord. There was no longer any symmetry or balance in the design, but fan tastic and restless curves with a luxury of applied ornamentation.

To the French smith it furnished the opportunity for a yet greater display of his skill. He was clever enough to secure a feeling of stability in his work by counterbalancing swirling masses or ornament with straight constructional lines ; he knew how to introduce an iron screen of rococo style into a Gothic church or cathedral without giving offence to the eye or arous ing any uncomfortable feeling of incongruity.

With astonishing manipulative power he worked as if the ma terial under his hand were soft and pliable rather than solid and unyielding iron.

Later in the i8th century ironwork took on a more classical appearance, owing to the general study of ancient art, and many Greek and Roman details were introduced into the ornamenta tion. The amount of work executed was prodigious, and its beauty and cleverness may be seen in most cities of France.

As might have been expected, nearly all the adjacent countries were seized with the desire to imitate this French rococo style, England excepted. But their efforts in this direction were largely doomed to failure ; the style was to them exotic, and consequently their imitations are, as a rule, unsatisfying. This is particularly true of the Italian rendering, which has lost the cohesion of the original design and lacks its bold workmanship; it fails to excite admiration. On the other hand, the German smith not infre quently caught the spirit of the French designer, and showed himself his equal in power of execution. Such work as that in the palace of the prince-bishop at Wijrzburg stands comparison with the French work of the period. Switzerland made an attempt in the French style of the end of the i8th century, and the results, though lacking the strength of the French work, are by no means unattractive.

England.—The development of the art during the Renais sance period was very uneven in the various countries of Europe. The English smith fell behind and seemed to have lost interest, producing no very great or important work. He continued to make iron railings and indulged in a number of balconies. His activities were more or less confined to small objects for archi tectural application such as hinges, latches, locks and weather cocks. To this period belong the hour-glass stands of wrought iron generally fixed to pulpits or some convenient adjacent column; over i oo still remain in their original position. In the reign of Charles II. a revival of larger work seemed imminent, and the rebuilding of the London churches after the great fire furnished an opportunity for making hat-rails, sword and mace stands, stair-rails to pulpits and finely decorated wrought-iron suspension rods for the great brass chandeliers with which the churches were provided. The English smith was neither idle nor incompetent, but he was waiting for an impetus and an inspira tion for his work.

The opportune moment came towards the end of the 17th century. There was a growing interest in beautifying houses and laying out gardens and squares, and a consequent use for balconies, staircases and garden gates; the rebuilding of St. Paul's cathedral and the London churches was in full swing. The man to whom the credit is usually given for the revival of ironwork in England was Jean Tijou, a Frenchman who together with many of his Protestant fellow-craftsmen had been forced to leave his country owing to the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. After some years in the Netherlands he came to Eng land in 1689 where he enjoyed the patronage and favour of William III. and his queen. His most important works are to be seen in the immense mass of screens and gates with which he embellished Hampton Court palace for his royal patrons ; they show an excessive amount of foliage and other ornament in sheet-iron beneath which the construction lines are almost lost, but Tijou was primarily rather an embosser than a smith. He executed work at Burleigh house, Stamford, and elsewhere ; and probably by the queen's wish was associated with Sir Chris topher Wren then engaged on the rebuilding of St. Paul's cathe dral. Wren apparently was not very keen on ironwork, and prob ably exercised some restraint on Tijou with the result that his work at St. Paul's is more serious and dignified and freer from appendages than that at Hampton Court.

How far did the English smiths follow Tijou's lead? They possessed several useful qualities; they were careful observers and not mere copyists; they seldom lost sight of construction work or ignored the sense of stability that was essential ; their more staid and serious temperament was reflected in their work ; consequently they developed along lines of their own and pro duced a definite style. The early years of the i8th century saw the erection of many fine gates in London and the vicinity. One of the best known is that formerly at Devonshire house and now on the opposite side of Piccadilly. The names are known of several English smiths who proved themselves worthy suc cessors of Tijou though in a definitely English style. Thomas Robinson was associated with him at St. Paul's where his work is easily distinguishable from that of Tijou. He also made the great garden screen at New college, Oxford, and perhaps the gates to Trinity college.

At Derby and in the neighbourhood Robert Bakewell executed the noble screen at All Saints church, the gates to Etwall hall, Melbourne, and much other work. William Edney made the screens in the churches of St. Mary Redcliffe and St. Nicholas, Bristol, as well as the gates to Tredegar park near Newport. Robert Davies of Wrexham executed gates for Chirk castle and other work in the vicinity. In London there may be studied a great amount of fine ironwork of the i8th century in the form of gates, railings, lampholders, door brackets, balconies, stair cases; in almost every suburb may be seen gates and brackets. The precincts of the colleges of Oxford and Cambridge, as well as almost every old town in England, furnish a variety of hand some work. Throughout the i8th century the smith was a busy man ; the general tendency of his work, unaffected by the rococo movement, was towards a less ornate but more characteristically English style, perpendicular, severe, lofty and commanding, as contrasted with Tijou's French love of richness and mass of details. So far from Tijou dominating English work, the native craftsman brought his ideas into line with the national tempera ment and taste which lay in the direction of simplicity and a thoughtful recognition of the limitations of the material. At the end of the i8th century the work of the architect brothers Adam shows a departure from true smithing ; its slender delicate bars are enriched with rosettes, anthemion and other ornament in brass or lead. The effect is pleasing and harmonizes with the architecture with which it is incorporated.

Germany and Austria.

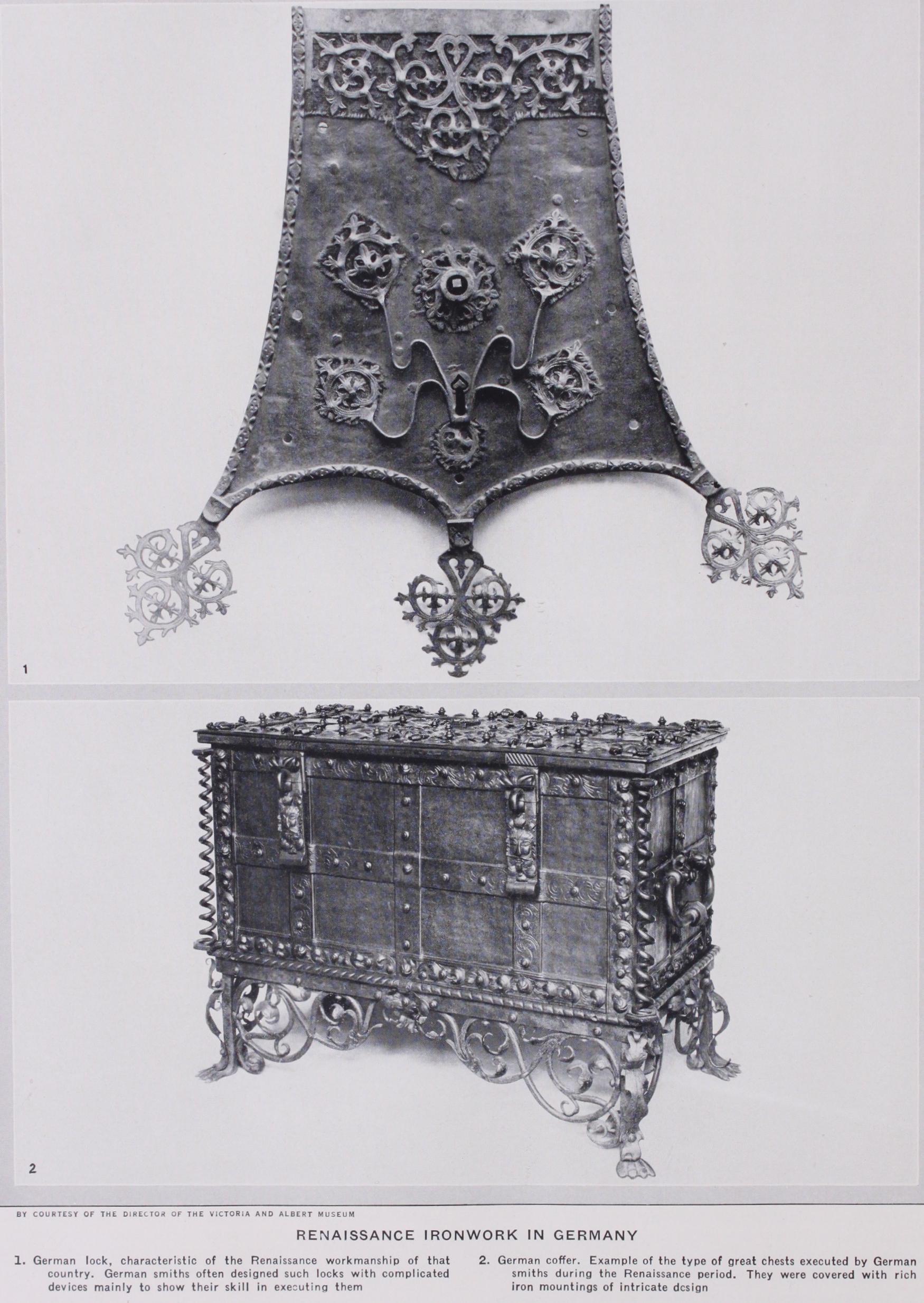

During the period of the Renais sance, ironwork in Germany showed a marked contrast to that of Italy. The metal was in use everywhere and for every purpose: for screens in churches, window grilles, stove guards, gates, fountain railings, well-heads, grave-crosses, door-knockers, han dles, locks, iron-signs and small objects for domestic use. Smiths were their own designers, and more often than not planned intricate devices merely to show their skill in executing them. They recognized no limits to their powers, and so far as manipu lative excellence went they were the foremost nation of Europe. But clever as their workmanship undoubtedly was, their de signs frequently showed a lack of stability and a tendency to run riot. Thus many of their most imposing works consist largely of filling of panels with elaborate interlacing scroll-work, and the sense of constructional and protective strength is lost sight of.

The greater amount of smiths' work is to be found in the southern parts of Germany. Iron bars of round section were most frequently used and the most common features are the threading backwards and forwards, terminations of flowers with petals and twisted centres, or of foliage or human heads. All of these characteristics occur with almost monotonous repetition, witnessing to the Teuton's skill in working, but also to his lack of imagination and power of de sign. The style may be studied in many German cities, i.e.,Augs burg, Nuremberg, Frankfort, Salzburg and Munich; the work at Innsbruck is also well known.

The German blacksmith gave much attention to door-knockers and handles, enclosing them in pierced and embossed escutch eons, also locks of very involved mechanism. Mention must also be made of the great boxes erro neously termed "Armada" chests, sometimes covered with rich iron mountings and having a lock with many bolts spreading over the whole of the inside of the lid.

German influence made itself strongly felt in Switzerland where the working of iron had established itself in the i 7th century. The intricate grilles and screens referred to above may be met with in the Engadine, and in more central parts of the country fine door fittings are found which are claimed, and probably with truth, to be of local manufacture. Scandinavia followed Germany in design and work. It must be remembered that ironwork had been an important industry in these countries from early mediaeval times.

The Low Countries.

Holland and Belgium were influenced by their neighbours, but there is no work of the importance of that produced in France or Germany. Another metal, brass, seems to have provided the outlet for their energy, and they were content to confine their work in iron to objects for domestic purposes. Cranes for raising the covers of fonts continued to be produced for churches, and grilles of trellis-work for the tabernacles; screens were rare. The quaint streets of such towns as Bruges and Ypres were rendered more picturesque by signs hanging from brackets of wrought iron, such as may still be seen in the Rue du Fil, Bruges. The facades of houses were deco rated with the date of their construction in large iron figures, or with wall-anchors whose device sometimes denoted the occupa tion of the owner; finials in the form of crosses or some fantastic device surmounted the gable ends; rich hinge and strap work strengthened the folding window-shutters.

Cast Iron.

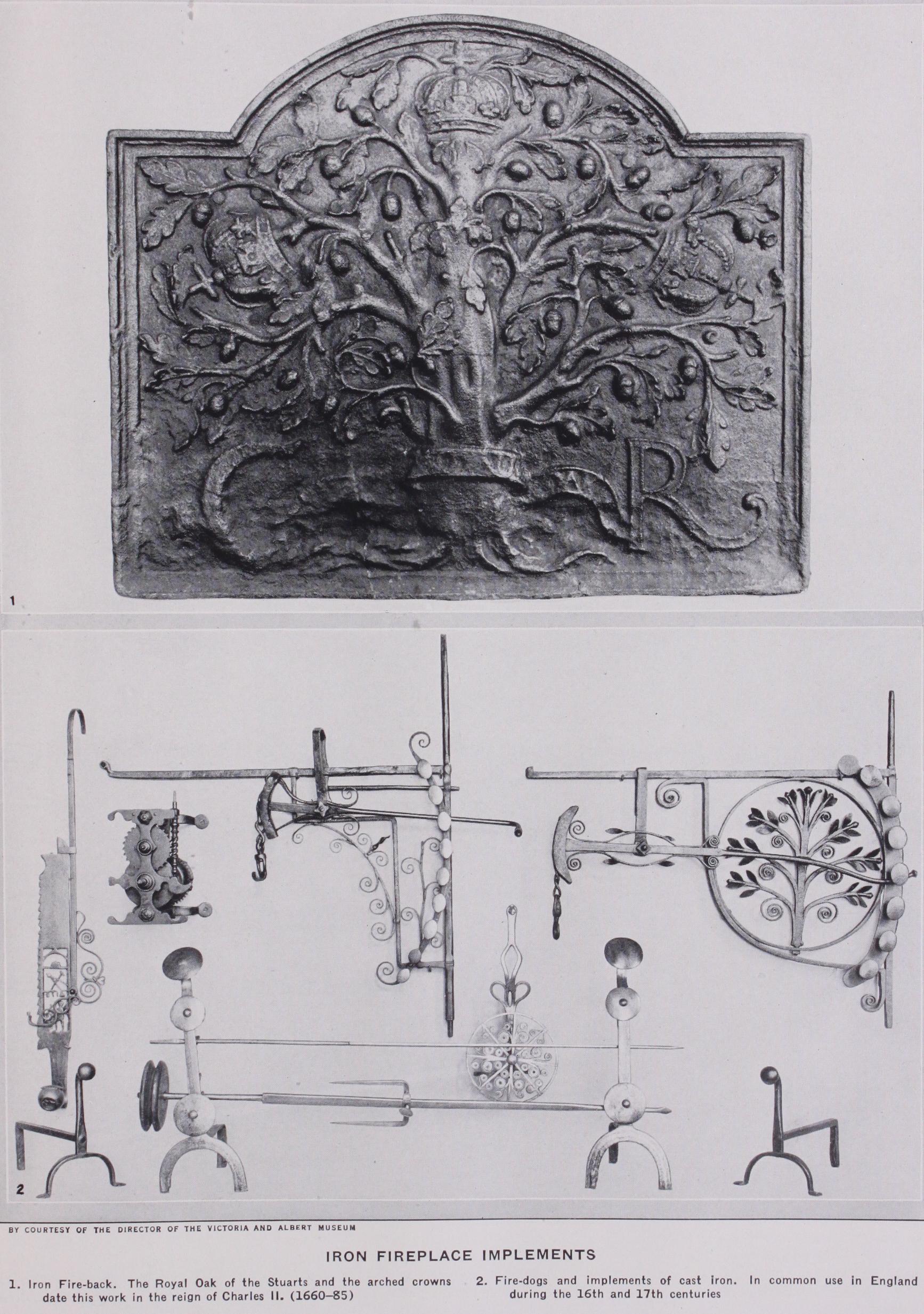

The casting of iron seems to have had rather a limited existence. In England the earliest known piece is a tombstone in Burwash church, Sussex, which dates from the 14th century. And it was not until the close of the following century that the introduction of open hearths and fire-places brought fire-backs and fire-dogs into common use. Designs of backs were many and various, at first the royal arms and insignia, and later any kind of decoration, in fact any handy piece of ornament, was pressed into use. The most highly valued are those with the royal arms or crests, or with fine heraldry. Fire-dogs were simple, the uprights being in the form of a column or terminal figure, sometimes supporting a shield of arms. The making of fire-backs and fire-dogs was virtually confined to the Weald of Sussex where it came to an end with the close of the 17th cen tury. The railing outside St. Paul's cathedral, London, is an old and important piece of cast work; however, it was not until the i9th century that cast-iron railings became general.

France also produced cast fire-dogs and fire-backs, the latter tending to greater refinement of style and execution than those of England. In Germany and the Low Countries fire-backs had their counterpart in the panels of stoves cast for the most part with scriptural subjects. Reference must also be made to the delicate "Berlin" iron jewellery cast in openwork with various designs at Ilsenburg in the Harz mountains, and as an act of patriotism substituted for the more precious metals to meet the exigencies of the Napoleonic wars. (See BRONZE.)