Anatomy of the Brain

ANATOMY OF THE BRAIN The brain is that part of the central nervous system which is contained within the skull. It is the seat of consciousness and memory and it contains the receptive centres for various sensory impulses which come from the skin, joints, muscles and organs of special sense. It has the power of originating movements and also of controlling and co-ordinating the action of muscles which are primarily innervated by nerve cells in the spinal cord and lower centres of the brain itself. Further it has the faculty of correlat ing the knowledge acquired by experiences, and of utilizing the deductions thus obtained for synthetic mental processes.

General Structure.

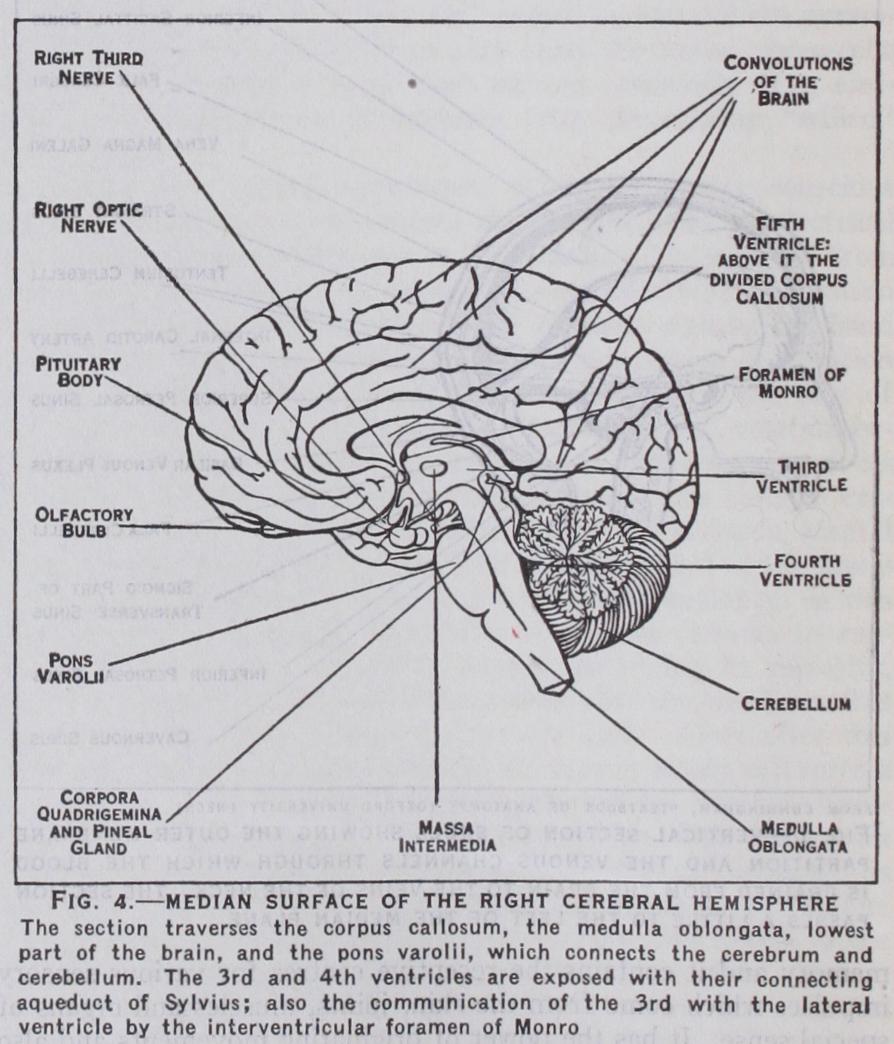

It consists of an upper main part, the cerebrum, and a hinder small part, the cerebellum (figs. 7 and 4). The lowest part of the brain, the medulla oblongata, is continuous through the foramen magnum with the spinal cord. The brain and spinal cord constitute the central nervous system, whereas the nerves passing to and from the central nervous system form the peripheral cerebrospinal system. The nervous system also in cludes certain nerve-centres and nerve-fibres which, without our conscious knowledge of the processes concerned, control the vital functions of the body, such as the circulation of the blood and respiration. This system, since it acts to a large extent inde pendently of the will, has been termed the autonomic system. It includes the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems. Through communicating branches the brain is capable of influencing organs which are supplied by the autonomic system, e.g., the salivary glands and heart, both of which may be acted on by fear. Under ordinary circumstances, however, the functions of the internal organs are carried out in a reflex manner, and without the indi vidual being conscious of the processes involved.

The brain is invested by three membranes. If the membranes are removed its surface is seen to be moist and of a greyish-white colour. It is characterized by sinuous foldings of the superficial stratum or cortex. These are the gyri or convolutions, and they are separated by grooves or sulci. The main part of the brain is sub-divided by a deep longitudinal fissure into right and left hemispheres. The hemispheres are connected by transverse bands of nerve fibres called commissures. The largest of these crosses the middle of the great longitudinal fissure and is called the corpus callosum (fig. 4). In addition to the hemispheres and cere bellum, the brain comprises the inter-brain or thalamencephalon, the midbrain or mesencephalon, the pons Varolii, which forms a transverse bridge between the two cerebellar hemispheres, and finally the medulla oblongata, which is situated below the pons and cerebellum and connects these with the spinal cord.

Membranes of the Brain.

These are an outer, tough, fibrous layer, the dura mater; a thin, intermediate, web-like tissue, the arachnoid mater, and a soft, vascular inner covering, the pia mater.The dura mater (fig. I), lines the cranial cavity. On its outer surface are meningeal arteries and veins which serve for the nutri tion of the bone. If torn in an injury to the skull an effusion of blood occurs between the dura mater and the bone, which, by exerting pressure on the underlying brain, causes paralysis of the opposite side of the body. The inner surface of the membrane which is in relation with the brain is smooth and moist. The dura mater also forms partitions between the hemispheres of the brain and cerebellum. These septa (fig. i) are folds of the dura mater and consist of two layers, blended where they touch but separated along the attached borders of the septa to form venous channels or sinuses, by which blood and also excess of cerebrospinal fluid is drained from the brain into the great veins of the neck which carry it back towards the heart.

The secretion from the pituitary gland (fig. 4) is also carried away into the general blood stream by small venules, which open into the neighboring cavernous and intercavernous venous sinuses (fig. I). Absorption of the cerebrospinal fluid is carried out, to a large extent, by small villous processes of the arachnoid mem brane which project into the venous sinuses and spaces of the dura mater, and are most numerous in the neighbourhood of the sagittal sinus (fig. 1). If this absorption is prevented or retarded the in tracranial pressure of the cerebrospinal fluid rises, and one form of hydrocephalus (q.v.) results. In old age the arachnoid villi enlarge to form Pacchionian bodies. Between the dura mater and the subjacent arachnoid membrane is an interval called the subdural space. It contains a small quantity of fluid which serves to lubri cate the smooth inner surface of the dura mater.

Beneath the dura mater is the arachnoid membrane, which is separated from the pia mater by an interval—the subarachnoid space. This is traversed by a network of delicate fibrous bands. The meshes of this network are filled by the subarachnoid cere brospinal fluid, while the larger thin-walled cerebral arteries and veins covering the surface of the brain lie in the thin bands of fibrous tissue forming the net.

The pia mater is the delicate vascular membrane which forms the immediate investment of the brain and dips down into the fissures between the convolutions. It contains the smaller arterioles and venules which supply the subjacent cortex of the brain. A large triangular fold of pia mater (velum interpositum) is included in the great transverse fissure lying between the corpus callosum and fornix above, and the roof of the third ventricle and optic thalami below (fig. 4). This pyramidal fold contains the two great cerebral veins of Galen, which drain the blood from the interior of the brain. Vascular fringes at the margin of the fold project into the lateral ventricles, and similar fringes project from the under surface of the fold into the third ventricle. These fringes are the choroid plexuses of the lateral and third ventricles, and a similar choroid plexus is found in the roof of the fourth ventricle. They are covered by a secretory layer, called the choroidal epithelium, whose function is to secrete the cerebrospinal fluid.

In the lower part of the roof of the fourth ventricle are three openings, a median, the foramen of Magendie and two lateral, the foramina of Luschka. These form a communication between the cerebrospinal fluid in the ventricles of the brain and that con tained in the subarachnoid space. Obliteration of these openings by meningitis produces an obstructive hydrocephalus, in which the accumulation of fluid is entirely intraventricular.

Ventricles.—These are cavities containing fluid situated in the substance of the brain and lined by a thin membrane, the ependyma. The true ventricles are four in number, namely, the right and left lateral ventricles, which are contained in the cerebral hemispheres; the third ventricle, situated between the optic thalami, and the fourth ventricle in the hind brain. Each lateral ventricle is connected with the third ventricle by a small opening, the interventricular foramen of Monro ; and the third ventricle is joined to the fourth by a narrow channel, the aqueduct of Sylvius (fig. 4). The fourth ventricle communicates below with the central canal of the spinal cord and with the subarachnoid space by the foramina of Magendie and Luschka.

The cerebrospinal fluid, which is contained in the ventricles and subarachnoid space, acts as a mechanical support to the brain and spinal cord ; it also takes the part of the tissue-fluid and lymph found in other parts of the body. (See NEUROPATHOLOGY.) Medulla Oblongata.—This is situated in the lower and pos terior part of the cranial cavity. It appears to be a direct continu ation upwards of the spinal cord, but differs from this in the arrangement of the fibres composing the nerve tracts and in the disposition of the grey matter. It contains the important vital centres known as the cardiac, vasomotor and respiratory centres. These are situated in the lower part of the floor of the fourth ventricle (fig. 2) . Longitudinal bundles of nerve fibres connect the medulla oblongata with the pons Varolii, and two diverging bun dles of fibres called restiform bodies join it to the cerebellum.

The principal longitudinal tracts which connect the pons with the medulla on each side are (r) the pyramidal tract, (2) the posterior or median longitudinal bundle, and (3) the median lem niscus or fillet.

(i) The pyramidal tracts consist of motor fibres each of which descend from the motor area of the cerebral cortex through the internal capsule, midbrain and pons to the anterior part of the medulla (figs. 9 and 3) . Here they form two parallel strands, one on each side of a median vertical groove. In the lower part of the medulla oblongata the greater number of the fibres of the pyramidal tract cross over to the opposite side of the spinal cord, where they form a bundle of descending fibres called the crossed pyramidal tract. The re maining fibres are continued downwards on the same side of the cord as the direct pyramidal tract. Eventually these fibres also cross to the opposite side. (See SPINAL CORD.) The cross ing of the motor nerve fibres in the medulla oblongata is called the decussation of the pyramids; and since, with few excep tions, all motor fibres, and also sensory fibres, cross to the opposite side, each cerebral hemisphere dominates the muscles of and receives sensory impulses from the opposite side of the body.

(2) The median longitudinal bundles are paired tracts of nerve fibres, which connect the nuclei of origin of certain cranial nerves, on the same side of the brain, with one another, and also by means of decussating fibres with nuclei on the opposite side. Each bundle extends from the midbrain, through the pons Varolii to the lower part of the medulla oblongata. By means of these tracts the nuclei of origin of certain nerves controlling bilateral movements are correlated, e.g., the muscle which draws the left eye towards the median plane will act in harmony with the muscle which draws the right eye away from the median plane.

(3) Each median fillet (fig. 4) is a longitudinal tract of ascen ding sensory fibres lying close to the median plane, between the pyramidal tract and the median longitudinal bundle. The fibres of the right and left tracts cross the median plane, forming the sensory decussation. This lies above the level of the motor or pyramidal decussation. The median fillets thus carry the sensory fibres coming from one side of the body to the central ganglia of the opposite cerebral hemisphere.

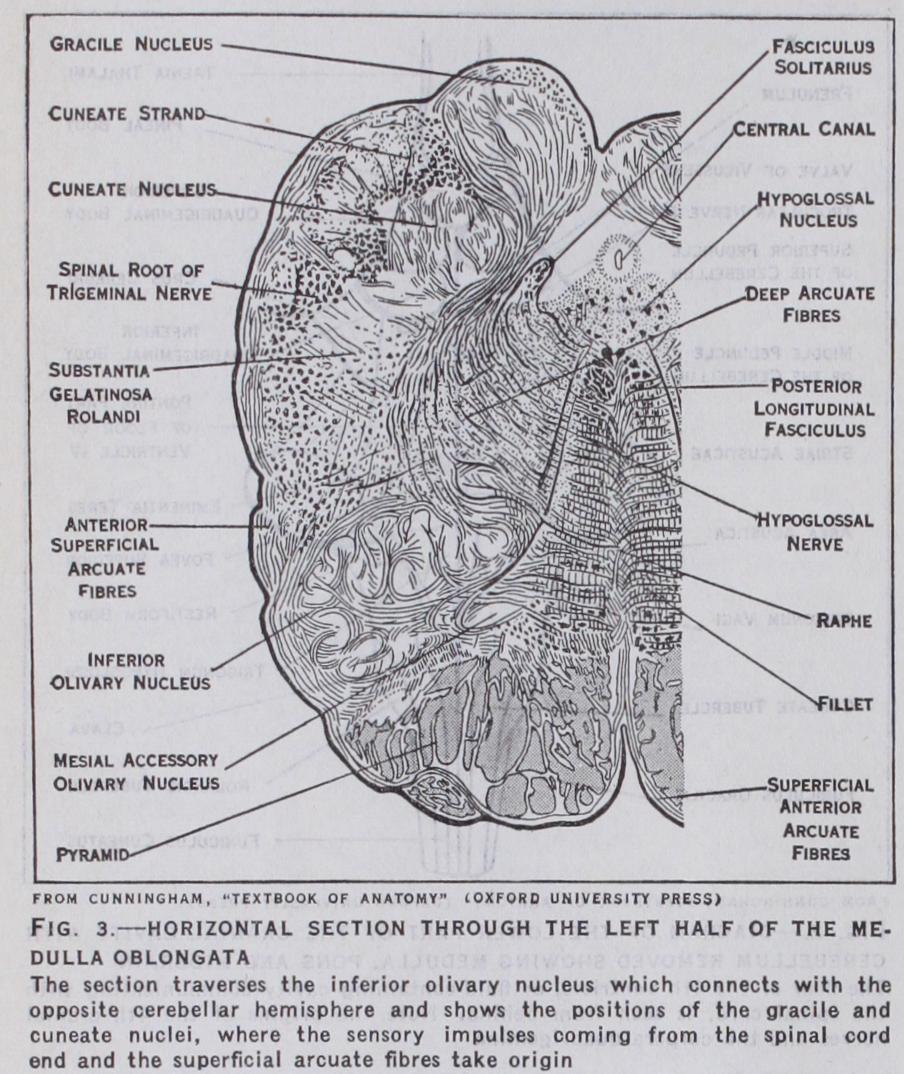

The sensory impulses coming from the spinal cord end in cell stations in the medulla, the gracile and cuneate nuclei (fig. 3) . It is from these that the superficial arcuate fibres, which pass to the cerebellum, and deep arcuate fibres (median fillet) take origin.

The latter thus form one link or relay in the main sensory tract to the cortex. Immediately external to the pyramidal tract on the anterior aspect of the medulla is an oval swelling, the olive (fig. 9), and external to this the inferior peduncle of the cerebellum, or restiform body. The olive lies over a folded lamina of grey mat ter in the substance of the medulla (fig. 3) ; this is the inferior olive. It is connected with the opposite cerebellar hemisphere by fibres which cross the middle line and reach the cerebellum by means of the restiform body. The superficial origin of the lower cranial nerves from the 6th to the r 2th is shown in fig. 9 ; the nuclei from which the motor fibres originate and those in which the sensory fibres terminate lie in the substance of the medulla and pons. Like the spinal nerves they are connected by tracts of nerve fibres with the opposite cerebral hemisphere.

Pons Varolii.

This (figs. 4 and 9) lies between the medulla oblongata and midbrain and forms a bridge which connects the two cerebellar hemispheres. It forms, by its posterior surface, the upper half of the floor of the fourth ventricle (fig. 2) . It con tains the nuclei of origin or termination, of the fifth, sixth, sev enth and eighth cranial nerves. A conspicuous band of trans verse fibres lies superficially and crosses beneath or ventral to the pyramidal fibres, which pass through the pons from the internal capsule and midbrain to the medulla oblongata. Some of the trans verse fibres, however, lie more deeply and intersect the longi tudinal fibres of the pyramidal tract. Most of the transverse fibres arise from nuclei of the pons which are connected with the cortex of the frontal and temporal lobes of the cerebrum on the same side, and crossing the midline eventually reach the cortex of the opposite cerebellar hemisphere. The most important longi tudinal tracts of nerve fibres traversing the pons are the pyramidal tracts, the longitudinal bundles, and the ascending sensory fibres of the median and lateral fillets. The lateral fillet is the main auditory tract which, arising from the terminal nuclei of the coch lear nerve of the ear, ascends to the midbrain and internal genicu late body.

The Cerebellum

consists of a central part, the vermis, and two lateral hemispheres. Each hemisphere is connected with the brain stem by three peduncles : (r) the inferior or restiform body of the medulla ; (2) the middle or brachium pontis ; (3) the superior or brachium conjunctivum. The last-named joins the cerebellum to the midbrain and conveys efferent fibres, leaving the cerebellum and ascending to the important red nucleus in the opposite side of the midbrain (fig. 6).The cerebellum correlates sensory impulses from the internal ear, and also from muscles and other organs. These efferent im pulses which reach the grey matter of the cortex of the cerebellum are believed to pass thence to the dentate nucleus, a convoluted lamina of grey matter situated in the substance of each cerebellar hemisphere. From this a relay of fibres ascends to the opposite red nucleus (see below for Midbrain). The superficial surface of the cerebellum differs from that of the cerebral hemispheres. In place of convolutions, the vermis and hemispheres of the cerebel lum are crossed by numerous transverse fissures, which mark off a series of folds or folia. The general arrangement of these is seen in a median section through the vermis, which presents a branched appearance called the arbor vitae. The surface of the cerebellar hemispheres and central lobe is subdivided into lobes and lobules by deep fissures, a full description of which must be sought in textbooks of anatomy.

Microscopical Structure of the Cerebellum.

The cortex of the cerebellum consists of a superficial stratum, the molecular layer, an intermediate layer which contains the cell-bodies of branched Purkinje cells (fig. 5), and an inner deep stratum, the granular layer which rests upon the central white matter. The latter is formed by medullated nerve-fibres which course to and from the grey matter. The Purkinje cells are remarkable for their large size and extensive connections. The cell-bodies are pear-shaped and arranged in a single layer. From the outer end of each cell, processes arise which branch out in the molecular layer.These processes are the dendrites, and the branching takes place chiefly in a plane at right angles to the longitudinal axis of the folium in which it lies. The dendrites of the Purkinje cells are intersected at right angles by parallel fibres which run in the direc tion of the folium. These fibres are derived from axons of the granule cells in the inner stratum of the cortex, which pass out wards and divide in the molecular layer in a T-shaped manner, into right and left branches. The bodies of the Purkinje cells are, moreover, surrounded by a network of fibres which originate from "basket" cells in the molecular stratum; and their branches are also accompanied by delicate tendril or climbing fibres, which are efferent nerve fibres from the white matter.

Although areas of the cerebellar cortex cannot be mapped out by response of particular groups of muscles to electrical stimula tion, it is possible on morphological grounds, by means of experi mental work and by the tracing of tracts of nerve fibres entering the cerebellum, to locate areas of the cortex according to the fibres which they receive from particular parts. Thus it is generally ad mitted that the head and neck are represented in the anterior part of the vermis, the trunk in the posterior part, and the limbs in the apical region of the vermis and hemispheres. References to liter ature on cerebellar localization will be found in C. J. Herrick, An Introduction to Neurology (1927) and H. Woollard, Recent Advances in Anatomy (1927).

The Midbrain

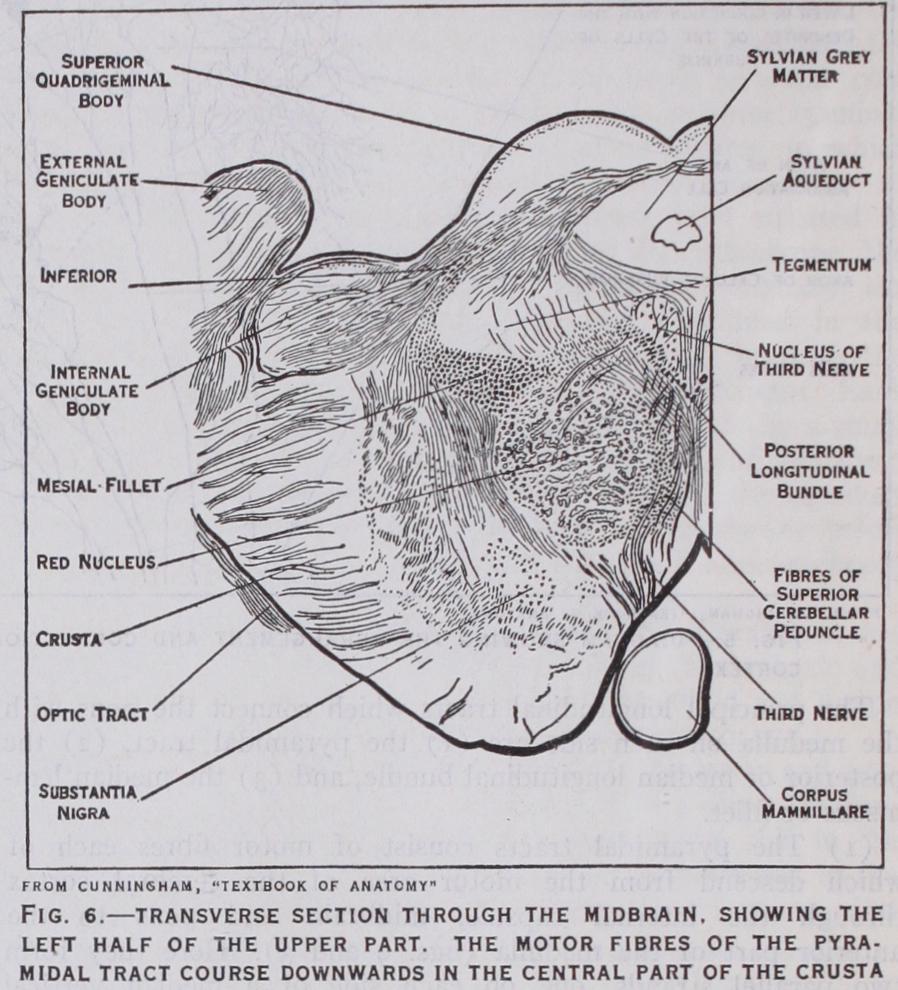

(mesencephalon) connects the parts below the tentorium cerebelli (fig. I) with the cerebral hemispheres above the tentorium. It is traversed by the aqueduct of Sylvius (figs. 4 and 6) . The part which lies above the aqueduct, called the roof plate or tectum, is subdivided by a crucial sulcus into four rounded swellings. These are the colliculi or corpora quadrigemina. The upper pair of these bodies receives nerve fibres from the retina, which reach them through the optic tracts. They are concerned in the regulation of the movements of the eye and in the pupillary reflexes. The lower pair serves as a cell station in the path of the auditory impulses which pass from the cochlea to the cortex of the temporal lobe. The grey matter in the roof of the aqueduct receives an important tract of nerve fibres from the spinal cord, known as the spino-tectal.A similar bundle, the spino-thalamic tract, also traverses the midbrain. Both tracts convey the more primitive sensations of pain, heat and cold to the receptive centres in the brain. These have been described by Head as protopathic sensations, to dis tinguish them from the finer and more recently evolved sensations of touch, which he terms epicritic. The latter ascend in the pos terior columns of the spinal cord to the gracile and cuneate nuclei (fig. 3) . From these a relay of nerve fibres ascends through the medulla oblongata, and crossing in this to the opposite side of the brain, passes as the median fillet through the pons and mid brain to the thalamus of the brain. From the optic thalamus an other relay of fibres carries the sensory impulses to the cortex of the brain. These fibres diverge as they traverse the white matter of the brain, thus forming part of the corona radiata.

The part of the midbrain which lies ventral to or below the aqueduct forms the crura cerebri. These are two diverging limbs which ascend from the pons Varolii to the right and left cerebral hemispheres (fig. 9). The superficial part (crusta) of each crus, (fig. 6), consists of motor and sensory nerve fibres. The former constitute a part of the great pyramidal tract which descends from the motor area of the cerebral cortex to the opposite side of the spinal cord. The sensory fibres pass from the frontal and temporal lobes to the pons, and thence to the opposite side of the cerebellum. Behind, or dorsal to the crusta, is a lamina of pigmented nerve cells (substantia nigra) which separates the crusta of one side from the corresponding side of the tegmentum. The latter con sists of two symmetrical halves, connected by a median raphe. This is traversed by decussating fibres, the greater number being the cerebellar fibres already mentioned as issuing from the dentate nucleus, travelling by the superior peduncle to the midbrain, and then crossing to the red nucleus of the opposite side (fig. 6).

From this important nucleus a tract of nerve fibres descends to the spinal cord, where it forms connections with the motor cells in the grey matter of the anterior cornua. (See SPINAL CORD.) This is the rubro-spinal tract of Monakow. The red nucleus is also connected with the central ganglia of the brain. By means of these connections, it is believed that the cerebral hemispheres control, through the red nucleus and rubrospinal tract, the more reflex movements carried out by the spinal cord, such as balancing movements and the maintenance of posture. If this controlling influence is interrupted, for instance by an injury to the mid brain, involving the red nucleus, rigidity, known as decerebrate rigidity, arises from overaction of the muscles. It disappears from any particular group of muscles if the sensory roots of the nerves coming from the corresponding area are divided.

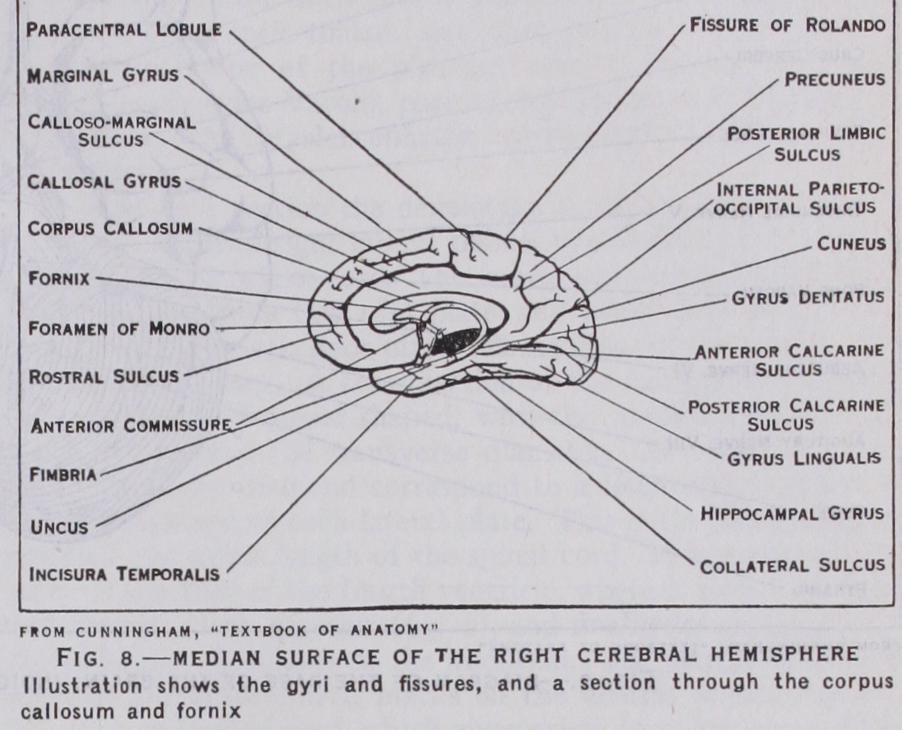

In the tegmental part of the midbrain are also situated the longitudinal association tracts, known as the anterior and posterior longitudinal bundles; and the fountain decussation of Meynert, which connects nuclei in the superior quadrigeminal body of one side with the nuclei of cranial nerves of the opposite side of the brain ; finally, the midbrain contains the nuclei and roots of origin of the third, fourth and part of the fifth cranial nerves, in the grey matter surrounding the aqueduct of Sylvius. (See NERVE.) Cerebral Hemispheres.—One of the most distinctive fea tures of the human brain is the large size of the hemispheres and the high degree of specialization in the microscopical structure of the cortex. The surface of each hemisphere is, for descriptive purposes, subdivided into lobes and lobules. Certain fissures and lines which are arbitrarily drawn between these are employed for demarcating the boundaries of these areas. The names of the principal fissures and lobes are indicated in figs. 7 and 8, and it will only be necessary to draw attention to certain of the more im portant. Thus the central fissure, or fissure of Rolando, is situated on the superficial surface and separates the frontal from the parietal lobe. The lateral fissure or fissure of Sylvius marks off the temporal lobe from the parietal and frontal lobes. On the median surface (fig. 8) are the calloso-marginal, the parieto occipital and calcarine fissures, which limit the frontal, limbic, parietal and occipital lobes.

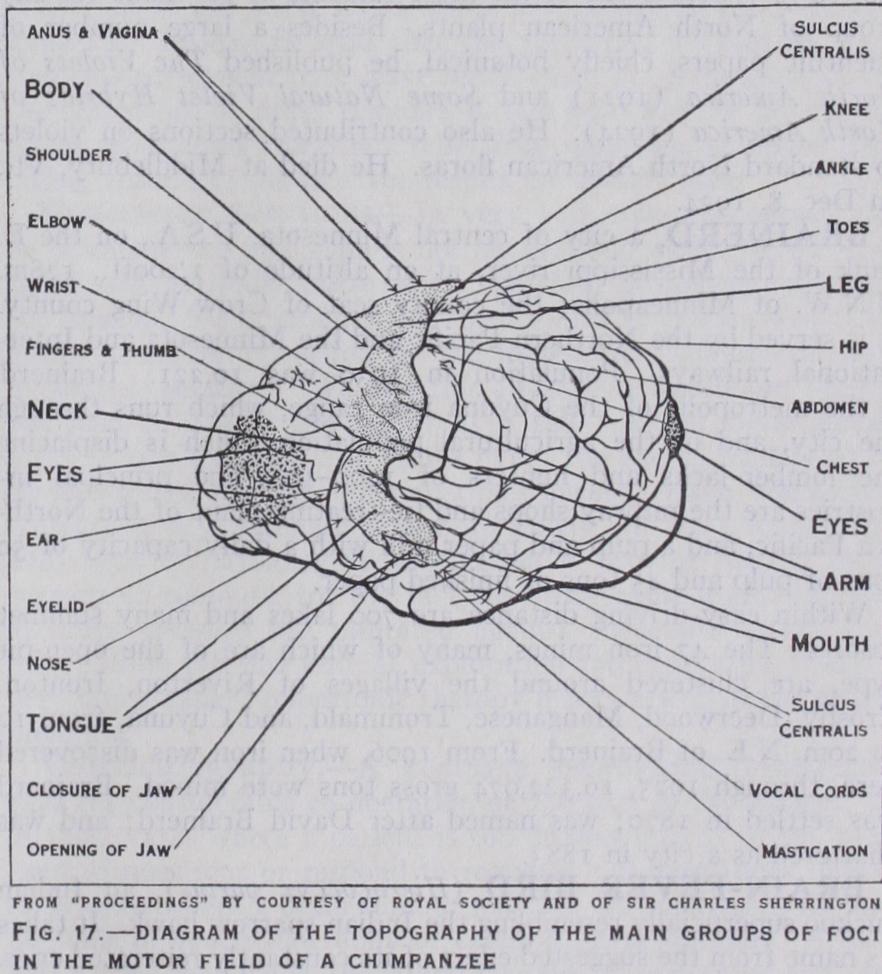

The central fissure marks the posterior limit of the important motor area of the cortex (fig. 17). Electrical stimulation of par ticular parts of this area produces definite movements of groups of muscles, the action of which is normally initiated and controlled by the part stimulated. Injury to the same part causes paralysis of the corresponding muscles. The cortex of the occipital lobe which surrounds the posterior part of the calcarine fissure is the visuo-sensory area for reception of visual impulses from the retina. The visuo-sensory area is surrounded by a marginal zone which extends on to the outer aspect of the occipital lobe, termed the visuo-psychic area. (See VISION.) The middle part of the first temporal gyrus and the adjacent gyri on the lower lip of the fissure of Sylvius are concerned with hearing (fig. 7). The auditory area of the brain receives sen sory impulses by way of the auditory radiation from the inferior corpus quadrigeminum and internal geniculate body of the same side. These, the lower auditory centres, are connected with the opposite ear by means of the lateral fillet.

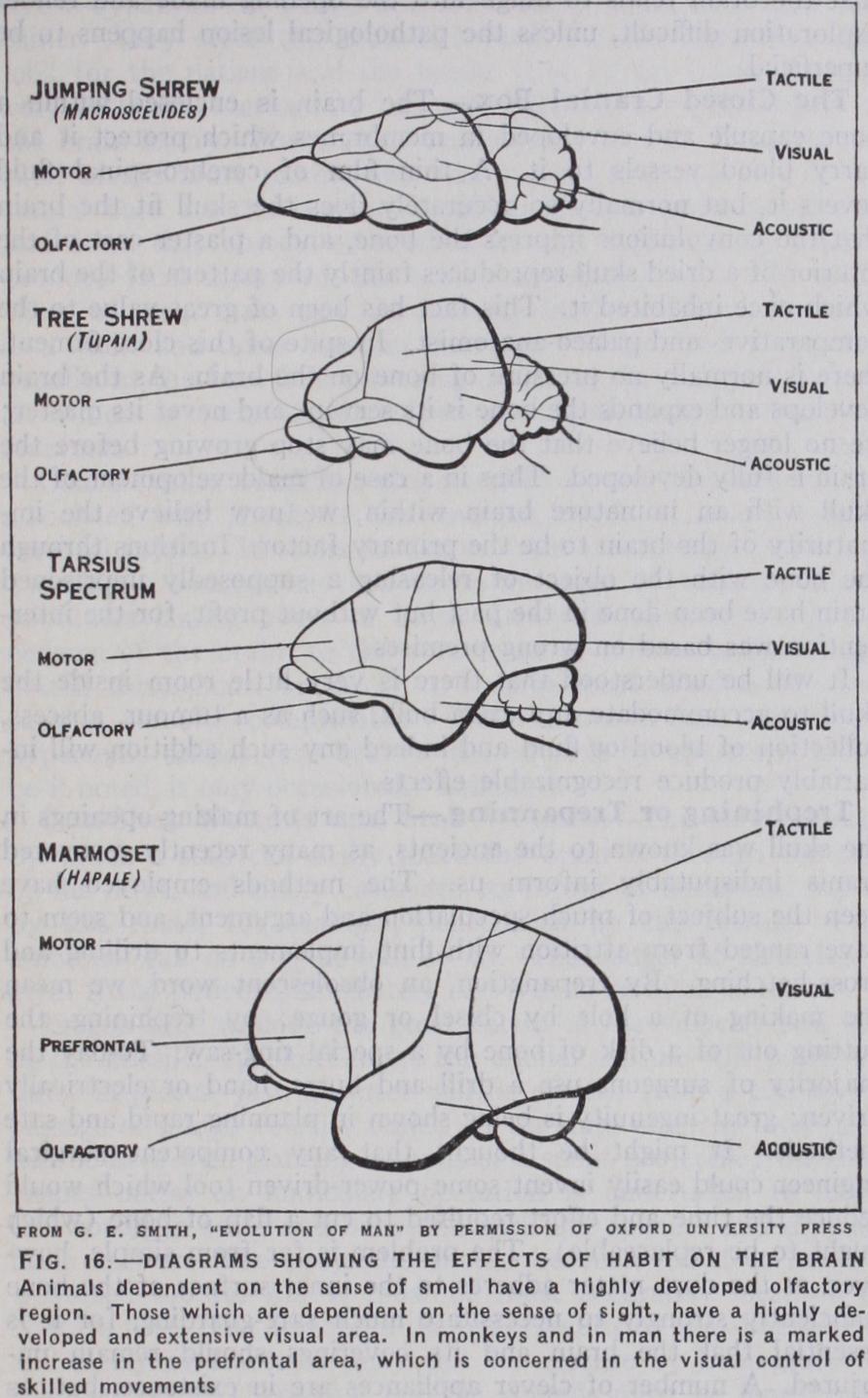

The front part of the hippocampal gyrus, with its hook-like end the uncus, is the higher cortical centre for the sense of smell This is the most primitive of the special senses. It is closely asso ciated with the sense of taste, and is both relatively and absolutely more highly developed in lower types of vertebrate animals than in man (figs. 8 and 16) . That part of the brain which is con cerned in the sense of smell is called the rhinencephalon. In ad dition to these, there is a large area behind the central fissure which extends forwards on to the motor area. This is the cutane ous sensory, or tactile area (fig. 16, D) .

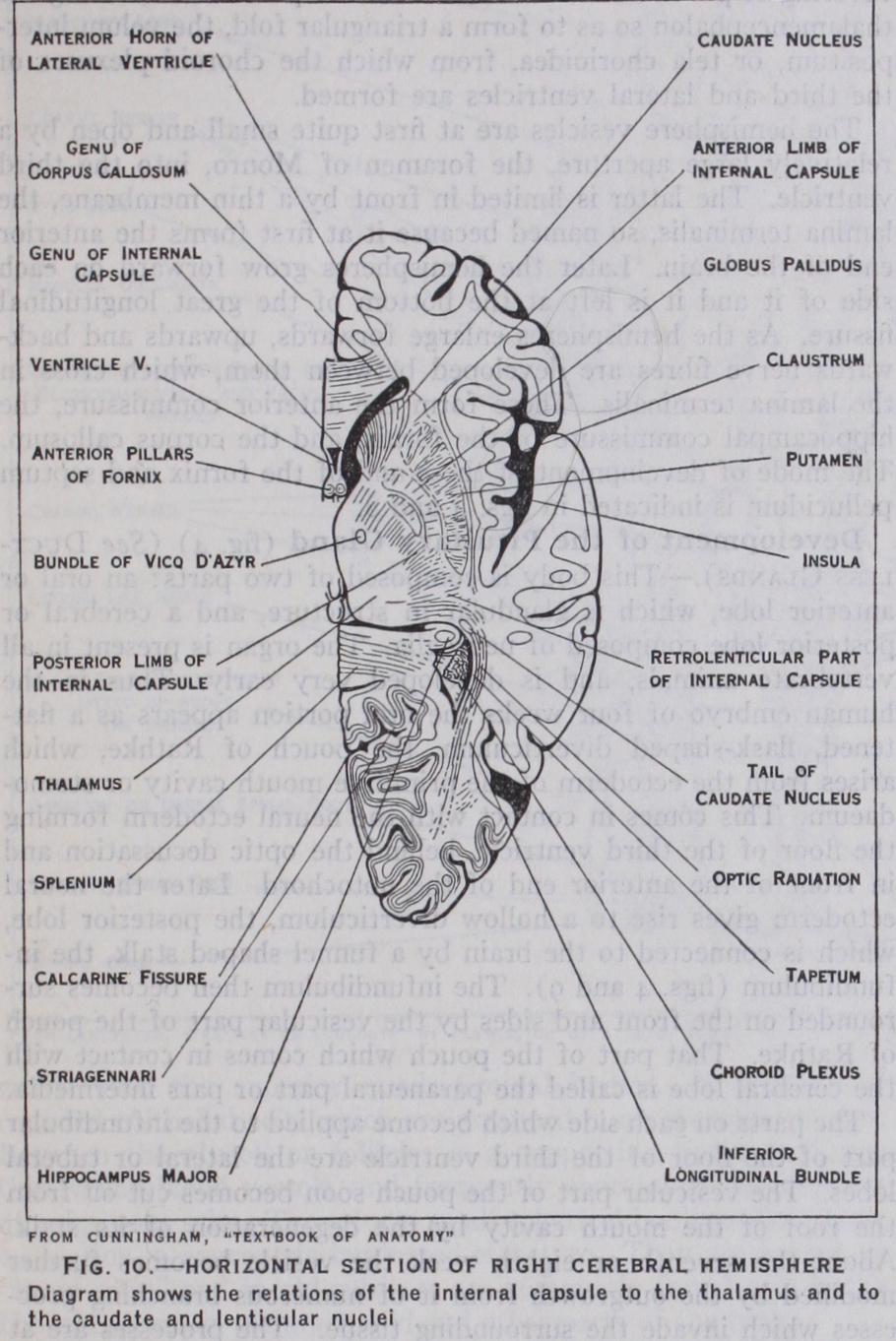

The areas of cerebral cortex lying between the special and cutaneous sensory areas are believed to function as association centres between the different senses, and as centres in which the memory of associated sensations is stored. The prefrontal region, which is more highly evolved in man than in any other animal, is connected by association fibres with all the various sensory and motor areas, and more especially with that part of the adjacent motor area which is concerned with the movements of the eyes. It is therefore believed that this part of the cortex may control skilled movements which are dependent on impulses reaching the brain from the eyes, and which require and a knowl edge or memory of past experiences. For instance, such move ments as those of the lips and tongue, or of the hand, which have given man the powers of speech and of writing. If the upper and lower lips of the fissure of Sylvius (figs. 7 and io) are separated a triangular area of submerged cortex will be exposed. This is the island of Reil, or Insula. It lies over the outer aspect of the cor pus striatum, and the lips of the fissure which overlap it are called the opercula insulae. In the human foetal brain, and the brains of most animals, this area of the cortex is exposed on the surface.

The basal ganglia are three masses of grey matter embedded in the cerebral hemispheres (fig. 1o). The basal ganglia consist of the optic thalami, the caudate and lenticular nuclei. The optic thalamus is a receptive centre for primary sensory impulses, and an important cell station in the path of sensory fibres to the cere bral cortex. The caudate and lenticular nucleus, with the white matter which surrounds the lenticular nucleus, form the corpus striatum. The white fibres lying to the inner side of the lenticular nucleus are called the internal capsule, those to its outer side form the external capsule. The former consists of sensory fibres pass ing to the cortex, motor fibres of the pyramidal tract passing from it, and association fibres passing between the nuclei.

The Cerebral Cortex

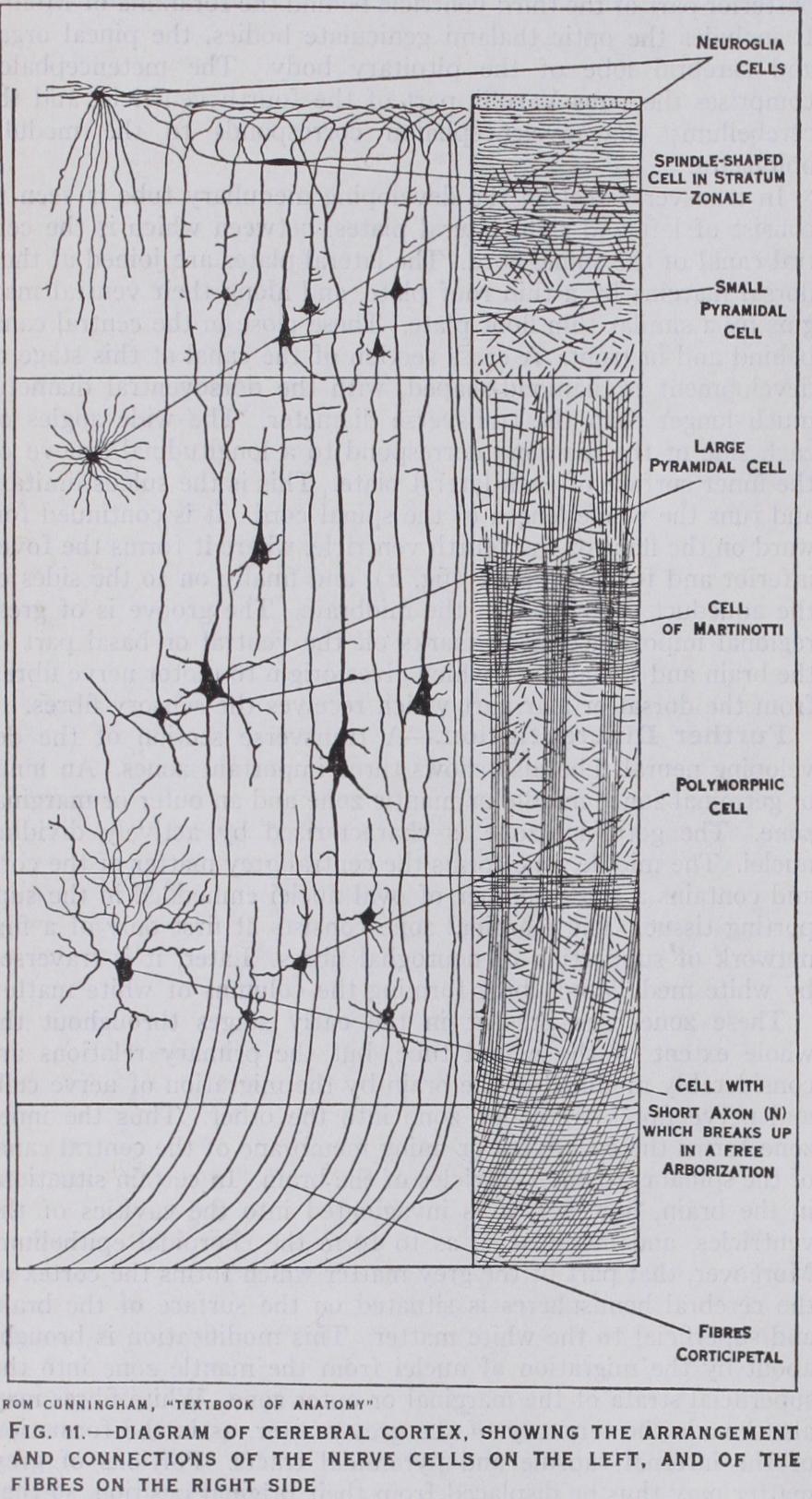

is the stratum of grey matter which covers the central white matter of the hemispheres. It consists of nerve cells, nerve fibres, and a supporting tissue—the neuroglia.It exhibits a definite stratification into layers of nerve cells and nerve fibres. In sections of the fresh brain, the main strata are easily recognizable by the unaided eye, and more especially so in the visual cortex, or area striata. Various zones may be distin guished in this way, and it is found that the naked eye appear ances correspond closely with the finer details revealed by micro scopic preparations. A general idea of the disposition and appear ance of the cell elements and nerve fibres will be gained by refer ence to fig. I I, in which isolated cells are depicted on the left and the fibre systems on the right.

It will be noted that the superficial lamina, or outer fibre layer, is largely composed of nerve fibres running tangentially or parallel with the surface. Many of these fibres are branches of the periph eral processes of small and large pyramidal cells contained in the subjacent strata of the cortex; others are the terminal branches of nerve fibres passing into the cortex from the white matter. These are called corticipetal fibres, and originate from nerve cells in the central ganglia, or from other parts of the cere bral cortex. The nerve fibres of the superficial lamina, and other strata in which the fibres are arranged tangentially, serve as asso ciation fibres, connecting different areas of the cortex with one another. They also connect fibres conveying sensory impulses reaching the cortex from the central ganglia or other parts with the cells which give rise to the efferent or outgoing impulses. Cer tain of these efferent, corticifugal fibres spring from the basal ends of the large pyramidal cells of Betz, present in the motor region of the cortex. They course inwards through the white matter to the internal capsule, where they converge to form the pyramidal tract. Other efferent fibres pass, by the corpus callosum, to the cortex of the opposite cerebral hemisphere.

In animals the degree of lamination and differentiation of the nerve-cells in the cortex appears to correspond with the stage of evolution attained by the particular species. The cortex is thicker and more highly evolved in man and the higher types of mammals than in lower forms. Moreover, in the development of the cortex, stratification begins about the sixth month of foetal life, when the convolutions first appear, and differentiation continues, not only during the later months of foetal life, but for a considerable period after birth. The more superficial strata containing the pyramidal cells are developed latest, and the human cortex is specially char acterized by the great development of these cells.

Weight of the Brain.

The weight of the brain varies with age, stature, body-weight, sex and race. It is also influenced by congestion of the blood-vessels, degenerative changes and atrophy. At birth the brain weighs approximately 38o grammes, and is I2.4% of the body weight. The entire brain, with the pia arachnoid of an adult British male, weighs approximately 1,409 g. or 49.6 oz., and of a female, 1,263 g. or 44.5 oz. The average stature and bodyweight of the female, however, is less than that of the male, and when these factors are allowed for the size and weight of the brain in the two sexes are approximately equal. The influ ence of age on brain weight is considerable. The growth of the brain is very rapid during the first three years, slightly less rapid up to the seventh year, when it is not far off its full weight. After this the increase is very gradual, its prime being usually attained, in males, by the 20th year, and in females somewhat earlier. From this period onward, in both sexes, there is a continuous diminution in the average brain weight of, approximately, I grm. per annum.Tall people have heavier brains than short, but, relatively to their height, short people have larger heads and brains than tall. Many men of conspicuous ability have had brains of large size, e.g., Cuvier (1,830 grm.), but on the other hand the brain of Anatole France, who died, aged 81, weighed, without the mem branes, only 1,017 grm. ; by adding 6o grm. for the weight of the membranes, and 61 grm. to allow for shrinkage due to age, his brain may be estimated to have weighed, at the age of 20, no more than about 1,138 grammes. Nevertheless, averages calculated from groups, e.g., scholarship and prizemen, average, and below average ability, show statistically that there is a small, though measurable correlation between large size of head and a high in telligence. The relation becomes still more apparent when the heads of the intellectual classes are compared with those of the lower classes, and more particularly the inmates of workhouse in firmaries and congenital idiots. The microcephalic type of the latter may have brains weighing only 30o grammes.

Development of the Brain.

The central nervous system originates as an axial thickening of the ectoderm covering the dorsal surface of the embryonic area. This is the neural or medul lary plate and is continuous on each side with the ectoderm, which will become the epidermis. The edges of the neural plate soon be come raised, so that the axial band is converted into a longitudinal groove. This is the medullary groove and already at its anterior end shows three enlargements which are separated by a couple of constrictions. These indicate the site of the primary divisions of the embryonic brain, namely :—the forebrain or prosencephalon; midbrain or mesencephalon ; and hindbrain or rhombencephalon. There is also an indication on each side of the forebrain of the optic vesicle.The medullary groove later becomes converted into a closed tube, which is named the medullary or neural canal, by the folding inwards and union of its edges. The union commences in the re gion of the neck and extends headward and tailward. The lumen of this tube is dilated at one end to form the ventricles of the brain, while in the rest of its extent it remains narrow and forms the central canal of the spinal cord. As the margins of the medul lary groove unite to form the medullary canal, a continuous lamina of epithelium grows outwards on each side of the spinal cord and posterior part of the brain. This is the neural crest. It afterwards becomes segmented, and gives origin to the sensory ganglia on the posterior roots of the spinal nerves, the sensory fibres of the spinal nerves, and the ganglia and nerve fibres of the sympathetic system It also takes part in the formation of some of the ganglia and nerve fibres of the cranial nerves.

It is of interest to note in this connection that the hypoglossal nerve which, in the adult, is a purely motor nerve for the supply of the muscles of the tongue, in the embryo has a posterior or sensory root with a rudimentary ganglion upon it (Froriep) . This afterwards disappears, but its temporary presence in the embryo indicates that the nerve was primarily composed of both motor and sensory fibres and that it is homologous with the spinal nerves.

Early Stages.—In the early stages of development the brain presents certain flexures which involve the longitudinal axis of the neural tube. The first of these is the cephalic flexure, which is a forward bend round the anterior end of the notochord. It is followed by the cervical flexure at the junction of the brain with the spinal cord, which is also in a forward direction. Between is the pontine flexure, which is in the reverse direction and does not involve the whole thickness of the neural tube.

The stage with three primary vesicles soon becomes modified by subdivision of the forebrain into an anterior telencephalon and a posterior thalamencephalon ; the hindbrain also divides into the metencephalon and myelencephalon. The telencephalon gives rise to the optic vesicles, olfactory lobes and hemisphere vesicles. The thalamencephalon forms the region of the brain surrounding the posterior part of the third ventricle behind the foramina of Monro. It includes the optic thalami geniculate bodies, the pineal organ and cerebral lobe of the pituitary body. The metencephalon comprises the pons Varolii, part of the fourth ventricle, and the cerebellum; the myelencephalon corresponds to the medulla oblongata.

In transverse section the developing medullary tube is seen to consist of left and right lateral plates, between which is the cen tral canal of the spinal cord. The lateral plates are joined at their dorsal margins by a thin roof plate, and along their ventral mar gins by a similar thin floor plate. These close in the central canal behind and in front. A cross section of the canal at this stage of development is diamond-shaped, with the dorsoventral diameter much longer than the transverse diameter. The wide angles on each side of the diamond correspond to a longitudinal groove on the inner surface of each lateral plate. This is the sulcus limitans and runs the whole length of the spinal cord. It is continued for ward on the floor of the fourth ventricle, where it forms the fovea inferior and fovea superior (fig. 2), and finally on to the sides of the aqueduct of Sylvius in the midbrain. The groove is of great regional importance, as it marks off the ventral or basal part of the brain and spinal cord, which gives origin to motor nerve fibres, from the dorsal or alar part which receives the sensory fibres.

Further Differentiation.—A transverse section of the de veloping neural tube also shows three important zones. An inner or germinal zone ; middle or mantle zone and an outer or marginal zone. The germinal zone is characterized by actively dividing nuclei. The middle zone forms the central grey matter of the cord and contains a large number of oval nuclei embedded in the sup porting tissue. The marginal zone consists at first only of a fine network of supporting or neuroglial fibres. Later, it is traversed by white medullated fibres forming the columns of white matter.

These zones are present in the early stages throughout the whole extent of the neural tube, but the primary relations are considerably modified in the brain by the migration of nerve cells and nerve fibres from one zone into the other. Thus the inner zone forms the ependyma or lining membrane of the central canal of the spinal cord and ventricles of the brain. In certain situations in the brain, however, it is invaginated into the cavities of the ventricles, and modified so as to form the choroidal epithelium. Moreover, that part of the grey matter which forms the cortex of the cerebral hemispheres is situated on the surface of the brain and superficial to the white matter. This modification is brought about by the migration of nuclei from the mantle zone into the superficial strata of the marginal or outer zone. White fibres may also invade the territory of the grey matter, as in the formation of the internal capsule and pyramidal tracts. Portions of grey matter may thus be displaced from their original position, so that the primary position of the parts becomes obscured.

In the later stages of development the primary flexures of the brain become, to a large extent, straightened out, and the whole form of the brain becomes modified by the enlargement of the cerebral hemispheres.

Hindbrain and Roofplate.—In the hindbrain a remarkable change occurs in the position of the lateral walls of the neural tube, whereby their dorsal margins formed by the alar laminae become widely separated. Each lateral plate is rotated outward through an angle of 9o° by a hinge movement, as in opening a book. The surfaces originally directed towards the median plane, thus become directed dorsally, and now form the floor of the lozenge-shaped fourth ventricle. The sulcus limitans still separates the basal (motor) and alar (sensory) region, but these, instead of being ventral and dorsal, are now internal and external (fig. 2.) .

The roof plate also becomes greatly modified, becoming thinned out and stretched so as to form a delicate epithelial lamina, which is blended with the overlying pia mater. A part of this mem brane becomes infolded just behind the cerebellum to form the choroid plexus of the fourth ventricle. The anterior part of the roof plate with the adjoining portion of the alar lamina becomes thickened to form the cerebellum, which is thus connected with the sensory tracts, and more especially with incoming impulses from the vestibular portion of the eighth cranial nerve. The median and lateral openings in the roof of the fourth ventricle are formed, secondarily, by a breaking down of the epithelial membrane. The cerebrospinal fluid is thus able to pass from the ventricles into the spaces of the subarachnoid tissue outside.

Midbrain and Thalamencephalon.

The midbrain in a i o mm. human embryo is characterized by the relatively large size of its central canal and its prominent position on the surface of the brain. At a later stage, owing to the growth through it of tracts of nerve fibres, from the cerebral hemispheres, cerebellum and pons Varolii, the walls of the canal become greatly increased in thickness, and the lumen becomes relatively small (fig. 6). Moreover, in the later months of foetal life, the midbrain be comes completely covered over and concealed by the backward growth of the corpus callosum and cerebral hemispheres.The thalamencephalon appears to undergo less change from the primary form of the neural tube than either the midbrain or hindbrain. It differs, however, in the absence of the basal or motor region, the motor functions of this part having been transferred to the motor area of the telencephalon. In the early stages of development the roof and lateral surfaces of the thalamencephalon are exposed on the superficial aspect of the brain. About the third month, however, the cerebral hemispheres, with the develop ing corpus callosum and fornix grow backward over the thalamen cephalon, mesencephalon and cerebellum, carrying with them a covering of pia mater. This fuses with the pia mater covering the thalamencephalon so as to form a triangular fold, the velum inter positum, or tela chorioidea, from which the choroid plexuses of the third and lateral ventricles are formed.

The hemisphere vesicles are at first quite small and open by a relatively large aperture, the foramen of Monro, into the third ventricle. The latter is limited in front by a thin membrane, the lamina terminalis, so named because it at first forms the anterior end of the brain. Later the hemispheres grow forward on each side of it and it is left at the bottom of the great longitudinal fissure. As the hemispheres enlarge forwards, upwards and back wards nerve fibres are developed between them, which cross in the lamina terminalis. These form the anterior con'imissure, the hippocampal commissure of the fornix, and the corpus callosum. The mode of development of these and of the fornix and septum pellucidum is indicated in figs. 4 and 8.

Development of the Pituitary Gland

(fig. 4) (See DUCT LESS GLANDS).-This body is composed of two parts: an oral or anterior lobe, which is glandular in structure, and a cerebral or posterior lobe composed of neuroglia. The organ is present in all vertebrate animals, and is developed very early. Thus in the human embryo of four weeks the oral portion appears as a flat tened, flask-shaped diverticulum, the pouch of Rathke, which arises from the ectoderm of the primitive mouth cavity or stomo daeum. This comes in contact with the neural ectoderm forming the floor of the third ventricle, behind the optic decussation and in front of the anterior end of the notochord. Later the neural ectoderm gives rise to a hollow diverticulum, the posterior lobe, which is connected to the brain by a funnel shaped stalk, the in fundibulum (figs. 4 and 9). The infundibulum then becomes sur rounded on the front and sides by the vesicular part of the pouch of Rathke. That part of the pouch which comes in contact with the cerebral lobe is called the paraneural part or pars intermedia.The parts on each side which become applied to the infundibular part of the floor of the third ventricle are the lateral or tuberal lobes. The vesicular part of the pouch soon becomes cut off from the roof of the mouth cavity by the degeneration of its stalk. About the seventh or eighth week the vesicle becomes further modified by the outgrowth from it of numerous branching proc esses which invade the surrounding tissue. The processes are at first hollow and lined by epithelial cells. Later the mesodermal tissue between the processes becomes vascularized, and the lumina of the processes and the main central cavity gradually become obliterated. The cavity of the posterior lobe also disappears, with the exception of a small recess in the floor of the fourth ventricle, which corresponds to the attachment of the infundibulum. In the adult the interior of the cerebral lobe is occupied by a loose net work of supporting neuroglia, and contains no nervous tissue, except fibres of the sympathetic system which accompany the vessels.

The meshes of the network contain a clear fluid. In the para neural part or pars intermedia, the epithelium is frequently ar ranged in the form of closed vesicles containing colloid material and this substance has sometimes been observed in the posterior lobe and in the region of the third ventricle, close to the infundi bulum, more especially in those animals in which the lumen of the cerebral lobe persists and remains in continuity with the cavity of the ventricle. The origin of the pituitary gland presents one of the most interesting problems of comparative embryology, refer ences to the literature on which will be found in any of the stand ard works on zoology and embryology mentioned in the bibli ography.

Pineal Organ or Epiphysis.

The pineal body of the human brain is a small conical structure (fig. 4) which springs from the posterior part of the roof of the third ventricle and projects back wards over the superior quadrigeminal bodies. It consists of rounded epithelial cells which are arranged in an alveolar manner. Between the alveoli or follicles is a supporting tissue enclosing thin-walled blood vessels, and frequently containing also deposits of calcareous salts. These form small spherical bodies which show, on section, a concentric laminated structure. They are known as "brain sand" and in old subjects are commonly found also in the choroid plexuses, pia arachnoid and other parts of the brain.The pineal body of man is a vestigial organ which represents a more highly evolved apparatus in lower types of living vertebrates, and probably a still more highly evolved apparatus in certain ex tinct reptiles such as the Ichthyosaurus. In one living reptile, the Tuatera, the pineal apparatus consists of two distinct (Sphenodon) organs—a glandular organ, the epiphysis, which is the structure present in the human brain, and a sensory organ, the "pineal eye"; this is situated in the parietal foramen, a central aperture in the vault of the skull, immediately beneath the scales covering the surface of the head.

In some of the lower vertebrate animals the pineal organ is bilateral, and it is believed that the ancestors of vertebrate ani mals possessed a pair of parietal eyes which may have been serially homologous with the paired vertebrate eyes. Transitional stages in the evolution of the pineal body from a bilateral to a mesial organ have been described by Cameron in the Amphibia.

Comparative Anatomy.

In the lowest types of vertebrate animals, the brain is tubular in form and resembles an early de velopmental stage of the brain in higher vertebrates. In the small lancelet or Amphioxus (q.v.) the brain consists of a median cere bral vesicle, the cavity of which is continuous with the central canal of the spinal cord. In the larval stage, an opening lined by ciliated epithelium, the neuropore, lies at the bottom of a funnel shaped depression, the olfactory pit. Viewed from the outside, there appears to be no distinction between brain and spinal cord.In front, at the pointed anterior end of the brain, is a median pigmented area. This is regarded as the rudiment of a median eye. A thickening of epithelium in the floor of the ventricle probably represents the infundibulum of the pituitary body. There are only two pairs of cranial nerves, both of which are sensory.

Cyclostomes.

In the cyclostomes, of which the lamprey (Petromyzon) may be taken as an example, the brain is much more highly developed. There is a distinction into forebrain, mid brain and hindbrain. There are well developed eyes with optic nerves ending in optic lobes (fig. 12). In the larva the fibres of the optic nerves, instead of crossing to the optic tract and lobe of the opposite side, as in higher vertebrates, appear to pass back to the optic lobe of the same side. It is probable, however, that in the later stages of development a decussation of some of the deeper fibres occurs in the floor of the fourth ventricle. The forebrain presents on each side two hollow vesicles, namely, the olfactory lobe of large size, and a rudimentary cerebral hemisphere behind. The two cerebral hemispheres are joined across the median plane by the lamina terminalis, in which there is already evolved a small anterior commissure.On the dorsal aspect of the thalamencephalon are two oval masses, the ganglia habenulae. The right of these is much larger than the left and from it a narrow stalk runs forward, to terminate in a minute pineal organ which contains vestiges of a pigmented retina and lens. A second pineal stalk which is even more vestigial than the right projects forward from the small left ganglion. There is also an indication of an additional outgrowth in front of the pineal organ, the paraphysis. The pituitary body is formed from a single median pouch, the pituitary sac, which opens primarily on the ventral aspect of the head, between the olfactory sac in front and the primitive mouth behind.

Later the pituitary sac sends out small follicular processes which fuse with the infundibulum and form, with the latter, the com pound pituitary gland. In the course of development the original openings of the pituitary and olfactory sacs are displaced from the ventral to the dorsal aspect of the head. In the hindbrain a rudi mentary cerebellum is present, which appears as a transverse bar at the anterior boundary of the roof of the fourth ventricle. The choroid plexuses are well developed and consist of three invagina tions, an anterior from the roof of the third ventricle, a middle in relation with the midbrain, and a posterior from the roof of the fourth ventricle.

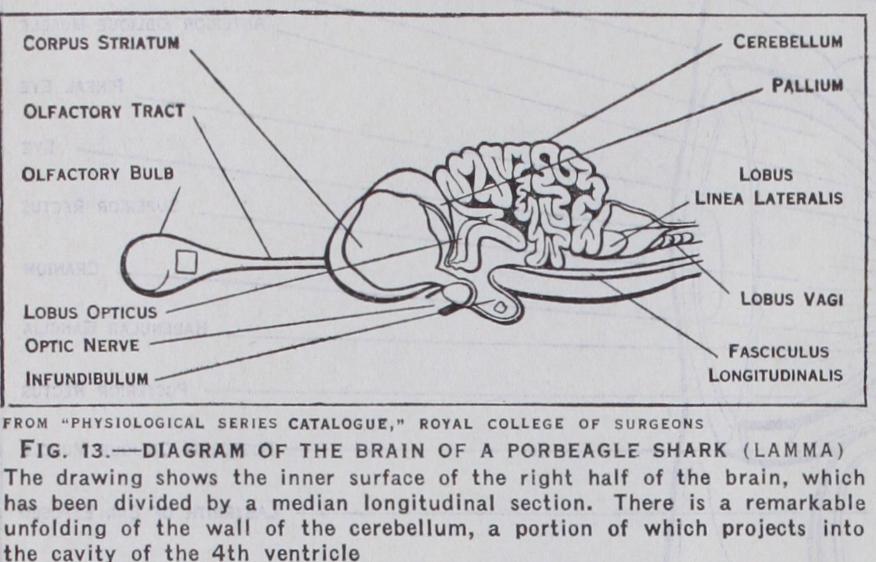

Fishes.—In the Selachia, viz., cartilaginous fishes, such as sharks, dog-fish and skates, the evolution of the brain is still fur ther advanced (fig. 13) . The development is chiefly in the tory part of the brain and the cerebellum. Although the eyes are fully developed, smell is probably the dominant sense, since the olfactory bulbs and tracts are enormous and project as large hollow outgrowths from each side of the forebrain. There is also a remarkable development of the cerebellum, more especially in the Porbeagle shark (Lamna), in which the cerebellar cortex is highly convoluted. The cerebral hemispheres are much larger than in the lamprey, the corpora striata are developed, and a roof plate or pallium is present; but as yet there is no differentiation of cortical layers. There is only one pineal stalk. The fibres of the optic nerves cross one another without intersection of fibres.

The brain of the Teleostei, or fishes having a bony skeleton, is in some respects not so far advanced as that of the cartilaginous fishes. The cerebral hemispheres and olfactory lobes are small. The optic lobes are, however, enormously developed, and the optic nerves cross one another without intersection of fibres.

In the mud fishes, or Dipnoi, the brain is elongated and tubular in form, the olfactory lobes large, and the cerebellum small. The brain, as might be expected, resembles in some respects that of the Amphibia.

Amphibia and Reptilia.

In the Amphibia the brain is tubu lar and does not show any distinct advance on the type charac teristic of fishes, and in some respects, e.g., the development of the cerebellum, is distinctly inferior to that of Lamna. The olfac tory lobes are large and in the frog's brain are fused in the median plane. In the lamina terminalis is developed an anterior or ven tral commissure, and above this a dorsal or hippocampal commis sure. The formation of the latter corresponds to the appearance of a small mass of cells in the superficial stratum of the median wall of the pallium. This is regarded by Osborn as the first indi cation of the hippocampal cortex. The epiphysis which is present in the larva disappears in the adult animal. There is a well de veloped infundibulum and hypophysis. The optic tracts and lobes • are of large size. The cerebellum appears as a small transverse bar in the anterior part of the roof of the fourth ventricle, and closely resembles that of the human embryo at the fourth week.

In the Reptilia (fig. 14) the cerebral hemispheres are more highly differentiated. The mesial surface of each hemisphere shows an upper hippocampal zone, a lower olfactory tubercle, and an intermediate part, the paraterminal body or precommissural area. On the upper part of the outer or lateral surface is a limited area, termed by Elliot Smith the neopallium. This is the fore runner of the large sensory and motor areas of the cortex which form the main part of the cerebral hemispheres in the higher mam malia. Below the neopallium is the piriform lobe, which is olfac tory in function and corresponds to the uncus of the human brain. The corpora striata are large, and there is an indication of differ entiation into caudate nucleus, globus pallidus and putamen. In the Lacertilia the pineal organ is more highly developed than in any living vertebrate animal. There is, however, no evidence of its use as an organ of sight.

Birds.

In birds (fig. 15), the cerebral hemispheres, optic lobes and cerebellum are large. The surface of the cerebral hemispheres is smooth, and their bulk depends largely on the great size of the corpora striata. The cerebellum consists of a large central lobe or vermis, crossed by a series of parallel fissures, and on each side a small but well-defined flocculus. The olfactory lobes are ex tremely small, and, judging from the early development and large size of the optic vesicles and the optic nerves and tracts, vision is the dominant sense.

Monotremes.

In the lowest Mammalia, represented by Ornithorhynchus and Echidna, the cerebral hemispheres are greatly developed. They extend forward over the olfactory lobes and backwards over the thalamencephalon, midbrain and cerebellum. Convolutions and fissures appear. There are a dorsal and ventral commissure, fimbria and gyrus dentatus. The cere bellum is well developed, presenting numerous folia and a con spicuous flocculus. In the spiny ant eater (Echidna), which is nocturnal in its habits, the optic nerves are extremely small, but there is an enormous development of the olfactory bulbs and tubercles.

Marsupialia and Insectivora.

In the Marsupialia the type of brain varies much, apparently according to the habits of the different species. Thus in the Tasmanian devil (Sarcophilus), described by Elliot Smith as an "offal eating animal," there is an enormous development of the olfactory bulbs and region of the brain termed rhinencephalon ; in kangaroos (Macropodidae), there is a great development of the neopallium and cerebellum.The Insectivora are remarkable for the very large size of their olfactory organs. In the mole the optic nerves and tracts and the superior corpora quadrigemina are poorly developed. The influ ence on the brain of change of habit in two members of the same family, the jumping shrew and the tree shrew, is strikingly de picted in the illustrations (fig. 16). (G. Elliot Smith, Essays on the Evolution of Man [1927].) The accompanying drawings of the brains of higher mammals, Tarsius spectrum and the marmoset, show the increase in the visual, acoustic and tactile areas which has taken place in these animals, and especially in the latter, of the prefrontal and association areas.

Higher Mammals.

The surface of the brain in mammalian animals varies greatly with regard to the convolutionary pattern. In some the hemispheres are smooth, e.g., the manatee, the lesser ant eater and the marmoset; in others, highly convoluted, e.g., the whales and dolphins, and certain ungulates such as the ele phant ; others are intermediate in this respect. The degree of convolution is partly dependent on the size of the body. As a rule large animals have highly convoluted brains; small animals, smooth brains. There is also a definite relation between the num ber of white fibres in the centre of the hemispheres and the num ber of nerve cells in the grey cortex on the surface.

In some animals, e.g., the Cetacea, with a highly convoluted pattern, the grey cortex is very thin. In the higher types of animals it is usually thicker and much more highly differentiated. The brain of the chimpanzee (fig. 17) closely resembles the convolu tionary pattern of the human brain. In most apes there is an ex tension forward of the peristriate (visual) area of the cortex on the outer side of the occipital lobe. This encroaches on and overlaps the parietal lobe and occipito-parietal fissure. It thus produces a transverse or lunate sulcus. This is the simian fissure or "affens palte," and is represented in the human subject by a small and variable fissure (S. lunatus) which usually lies some distance be hind, and external to, the external parieto-occipital fissure and is not continuous with it. The human brain is distinguished anatomi cally from that of the higher apes by its large size and great development of the prefrontal region. It is also characterized by a much greater complexity in the microscopical structure of the cerebral cortex. Mentally man is distinguished from the apes by the faculty of speech and by much greater power of reasoning, concentration and appreciation. See MAMMALIA; PRIMATES.