Brake

BRAKE. A means of controlling the speed of a movement, or of totally arresting it. Nearly all brakes act frictionally, though the opposition of a piston in a cylinder can be applied for retard ing purposes, converting the cylinder into an air-compressor for the while. Dynamic braking is another non-frictional method.

an electric motor being caused to run as a generator, so checking the speed of a vehicle or a machine, or causing a total stop. Most friction brakes act on revolving elements, as wheels or drums, but slipper brakes pressing on flat surfaces are applied as for tramcars, mechanically or magnetically operated, and a pincer or forcep type grips each flank of a rack in some of the mountain railways. A rope also serves for the application of a brake device in a few cases.

Band-brakes.

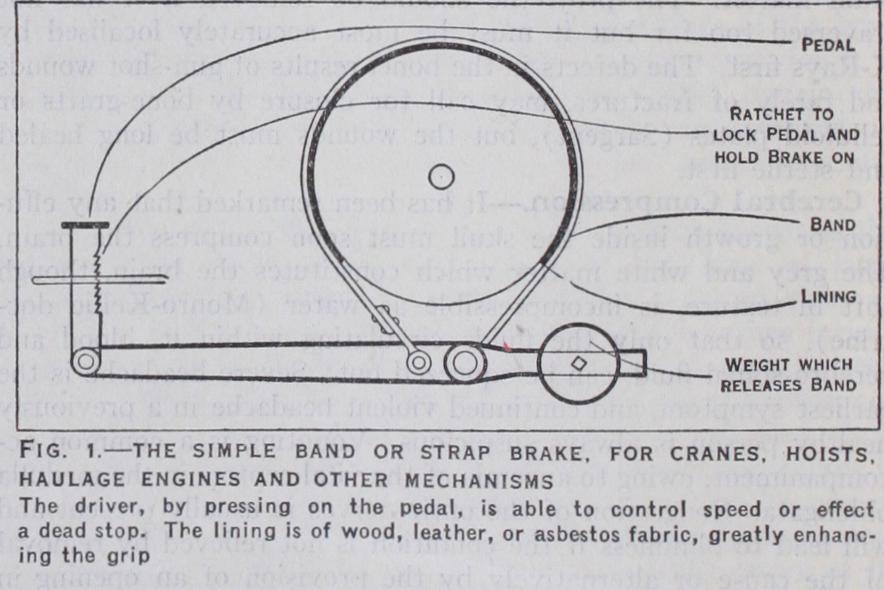

A highly effective braking action can be ob tained by the coiling of a rope around a drum, as may be seen at any docks, a man holding the free end of the rope, and allow ing it to slip gradually. The more convenient application of this idea (a flexible steel band) is employed on winches, hoists, haulage and winding engines, cranes and motor vehicles ; in order to in crease the frictional effort and reduce heating, some kind of lining has to be fitted, as wood, leather, asbestos or one of the special compositions. The band fits externally in all ordinary examples, but when access of dirt, moisture and grit must be pre vented, which is the requirement in motor-cars, an internal expand ing type has the preference, the band being made in two or three parts, with a pivotal freedom. By the multiplication of power with a lever, plus the frictional effect of the band embracing a large diameter, a man by exercising moderate force at a handle or treadle can hold a load of several tons, and pay it out slowly or quickly by regulating his pressure. Fig. i may be noted to explain the essential features, the lever having its eye pivoted on a short shaft around which one end of the band is looped, while the other end is pinned a little way along the lever, being conse quently pulled taut as the pedal is depressed. A balance-weight at the tail end frees the band when the foot releases the lever.

Electromechanical Brakes.

Electric cranes possess a simi lar kind of band-brake, but with a system of levers arranged so that a weight applies the band, excepting while the crane is work ing. As current is switched on, a solenoid acts on an electromagnet and pulls the lever; directly current is switched off, or fails from any cause, the weight asserts itself again. By a hand release mechanism lowering may be done, and automatic over-winding gear is usually fitted, which has the effect of applying the brake should the load be lifted too near the jib or girders. Not only the lifting motion, but slewing, derricking and travelling motions generally have electromechanical brakes, an important factor in high-speed operation.

Motor-car Brakes.

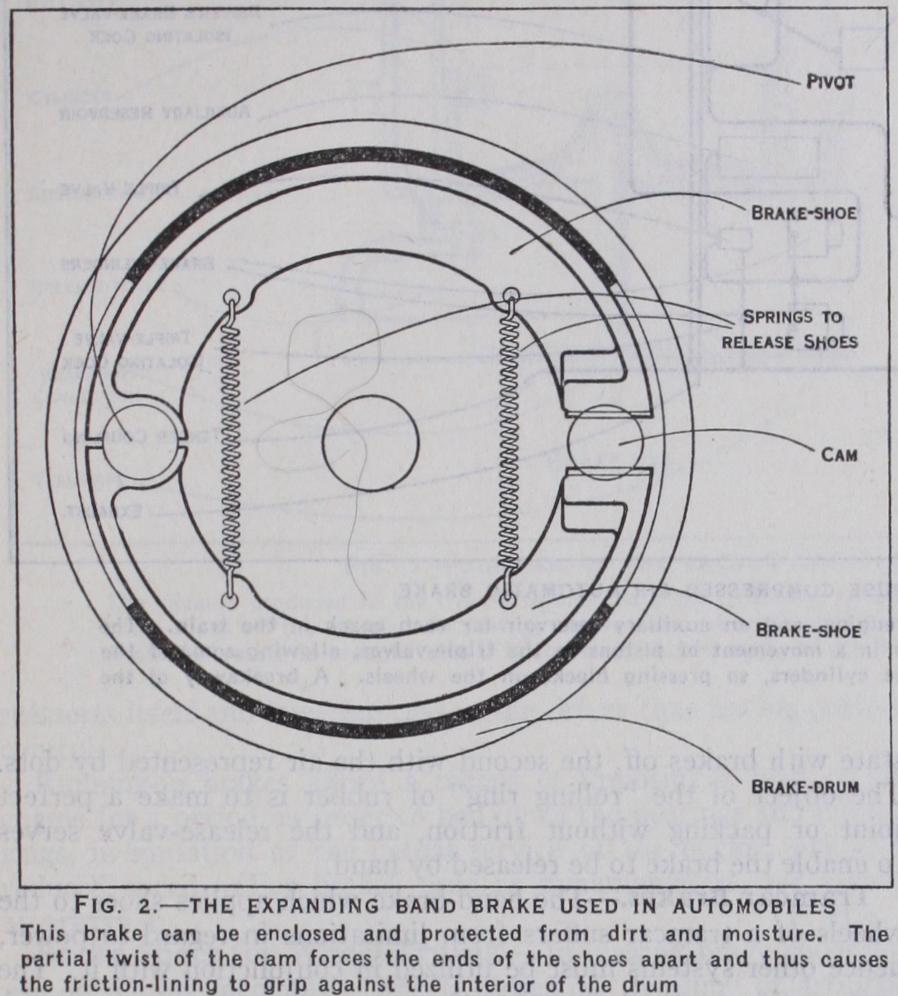

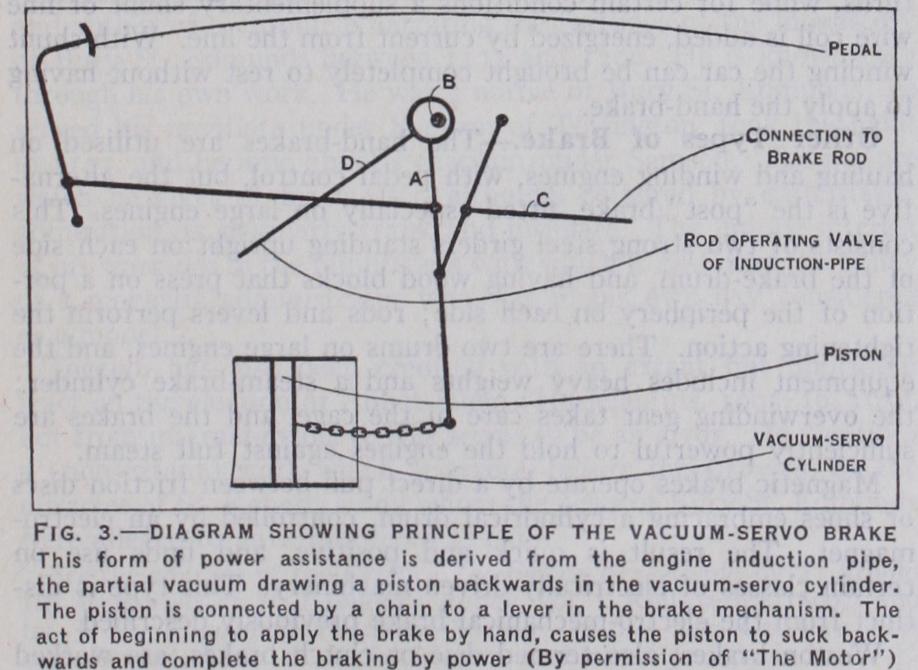

A special class of brake-drum arrange ment is built into many cars, with duplex shoes; for instance, the pedal actuates shoes in drums on the four wheels, while the hand-lever operates separate shoes in the rear wheel drums. The diagram (fig. 2), gives a face view of a drum, with the spring closed shoes, and the cam which spreads them apart. Rigid rods usually transmit the power from the hand-lever or pedal, but there is a class with steel ropes, termed a cable brake, forming the connection to the front and rear drums. Servo-mechanism operated from the gear-box works through clutchplates; first the rear brakes go on as the driver depresses the pedal, and then the clutch faces engage, and through levers augment the driver's effort, and also put on the front-wheel brakes. Or a connection is made to the engine so as to obtain suction on a piston in a servo-motor, the valve for this coming into use as the driver gradually applies the brake. Fig. 3 shows the system of levers in the Dewandre mechanism. As the pedal is pushed over it draws lever A forward until the clearance between its boss and the pin B is taken up, the brakes going on by the pull of rod C, the top end of which is really fulcrumed at the same spot B, though shown separated for clearness. Lever D now functions and places the suction manifold in communication with the brake cylinder, and the air is instantly sucked therefrom, setting the chain taut, and pulling over the bottom end of lever A.

In the Westinghouse vacuum-servo system a brake cylinder has one end open to atmosphere, the other end communicating with the engine induction-pipe through a control valve which regulates the resultant pressure on the piston. The brake levers are so devised that application of the brake pedal first brings the brake shoes into contact with the drums; then further foot pressure affects the control valve and opens the communication between induction-pipe and brake cylinder, thus causing the pressure of the atmosphere to move the piston and tighten the brakes still more. The braking force is directly dependent on the foot pressure.

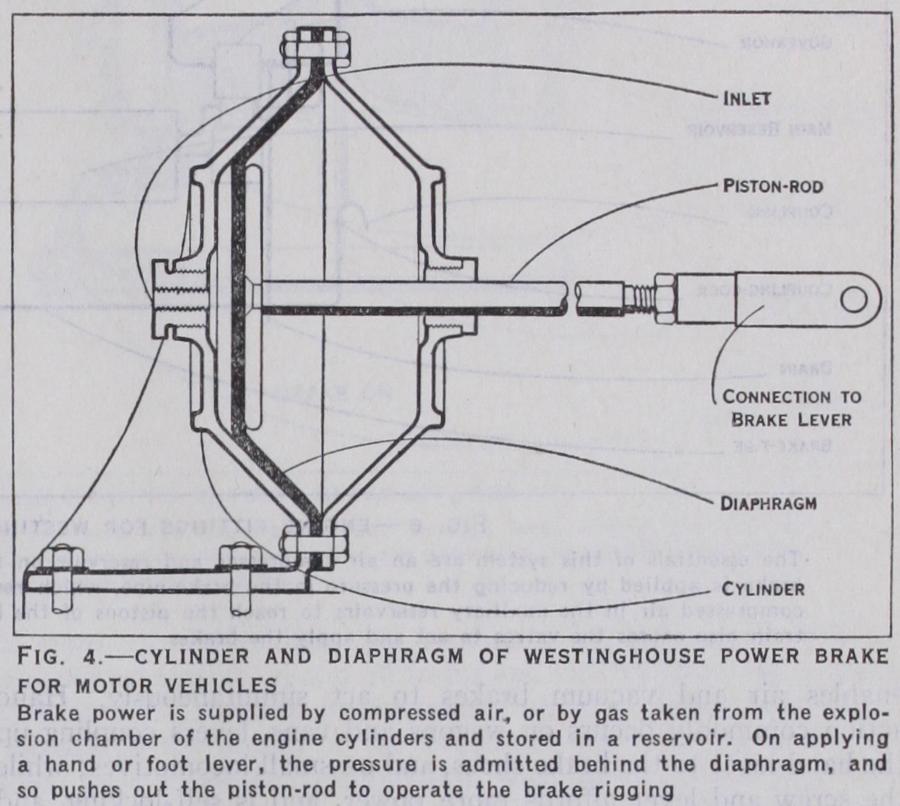

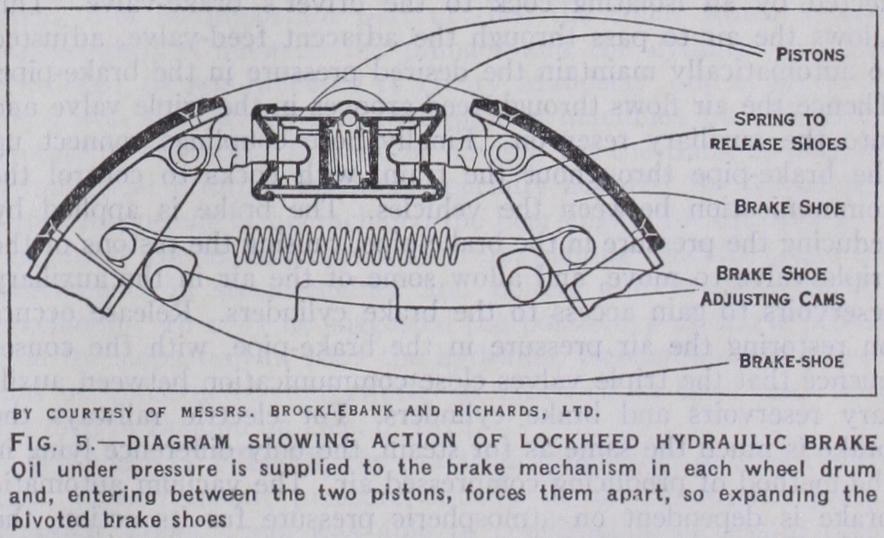

The Westinghouse power-brake acts by air from a small com pressor or by gas from the explosion chamber of a petrol engine. The control may be exercised either by foot-valve or hand-valve, and the brake-cylinder for each wheel is in the form of a pair of covers, one with foot to bolt to the chassis. The cylinder diame ters range from yin. to rein. according to weight of vehicle. Instead of a sliding piston, there is a flexible diaphragm (see fig. 4) that moves as the pressure comes through the pipe joined up at the back cover, and pushes the rod outwards. The latter connects to a reversing crank, and so to the brake-rod. There is a slotted link fitment to the existing hand-brake to make this independent of the power-brake. Hydraulic power has the ad vantages of simple flexible pipe connections to the wheels, and a perfectly compensated action, since the pressure is equal in all directions. The Lockheed system, which is fitted to numerous makes of cars, has a small pump or master cylinder attached to the flywheel housing, forcing oil along pipes and through rein forced rubber connections to a cylinder in each brake assembly. Two small pistons in each cylinder expand the brake shoes, as evident from fig. 5 (from a Brocklebank car). The shoes are pivoted at the opposite side of the circle, in the usual manner. The pistons are r 4in. in diameter, and the normal pressure is about r oolb. per sq. in., rising to 3 5olb. in emergency. The fluid used is a mixture of equal parts of castor-oil and ether, and certain stabilising ingredients added.

Railway Brakes.

These comprise hand-lever brakes for small locomotives and trucks and wagons, screw and lever for vans and tenders, etc., steam for locomotives and sometimes tenders, Westinghouse air-brakes for whole trains, and vacuum brakes. The mixed system is also employed, an air-brake being used for the engine wheels, and vacuum for the train ; or a steam-brake acts for the engine and vacuum for the train. A special valve enables air and vacuum brakes to act simultaneously. Hand action commonly occurs on wagons and vans, levers coupling up the hand-lever to the brake shoes, and on small locomotives; while the screw and lever affords more power, and is self-locking, and serves for small locomotives, the tenders and some vans. Steam is applied largely in the case of driving wheels, one cylinder actuating the rods for several shoes ; a separate arrangement with flexible connection is frequently fitted to bogies ; or, as alterna tive to the steam, the vacuum brake, or Westinghouse, takes charge of the engine wheels.The Westinghouse automatic brake operates by compressed air furnished by a compressor on the engine, and stored in its main reservoir. The essential parts include those indicated in the diagram (fig. 6), commencing at the steam stop-valve, supplying steam through the air-compressor governor. The last-named shuts off steam when the required air pressure is reached. The com pressor passes air into the main reservoir, which is directly con nected by an isolating cock to the driver's brake-valve. This allows the air to pass through the adjacent feed-valve, adjusted to automatically maintain the desired pressure in the brake-pipe. Thence the air flows through feed grooves in the triple valve and into the auxiliary reservoir. Finally hose couplings connect up the brake-pipe throughout the train, with cocks to control the communication between the vehicles. The brake is applied by reducing the pressure in the brake-pipe, causing the pistons of the triple valve to move, and allow some of the air in the auxiliary reservoirs to gain access to the brake cylinders. Release occurs on restoring the air pressure in the brake-pipe, with the conse quence that the triple valves close communication between auxil iary reservoirs and brake cylinders. For electric railways the brake is much the same as for steam, the only difference lying in the method of producing compressed air. The vacuum automatic brake is dependent on atmospheric pressure for its action, the brakes being normally kept off by the state of vacuum existing in the train-pipe and cylinders. An ejector on the engine produces the vacuum and maintains it constantly. As there is vacuum both above and below the pistons in the brake-cylinders, the pistons fall by gravity and the shoes remain off. But when atmospheric air is admitted to the train-pipe, by the driver or guard, or through a break-away, it closes a ball-valve in the piston so as to seal the upper side of the cylinder, and exerts pressure on the lower side of the piston, forcing it upwards and actuating the brake rods. The two conditions appear in fig. 7, the first view showing the state with brakes off, the second with the air represented by dots. The object of the "rolling ring" of rubber is to make a perfect joint or packing without friction, and the release-valve serves to enable the brake to be released by hand.

Tramcar Brakes.

The hand-brake which applies shoes to the wheels of a tramcar suffers from limitations in regard to power, hence other systems must be utilized in conjunction with it. The regenerative method (causing the motors to act as generators) imposes a powerful braking effect. Or this may be combined with the operation of slippers magnetically clinging to the rails (an alternative to mechanically-applied slippers), thus affording axle braking combined with the powerful slipper drag. And sometimes the mechanism includes wheel shoe attachments, the drag of the magnets causing an application of the wheel brake blocks. The magnet coil is usually a large wire coil having a small number of turns, while for certain conditions a supplementary shunt or fine wire coil is added, energized by current from the line. With shunt winding the car can be brought completely to rest without having to apply the hand-brake.

Other Types of Brake.

The hand-brakes are utilised on hauling and winding engines, with pedal control, but the alterna tive is the "post" brake, fitted especially on large engines. This consists of two strong steel girders standing upright on each side of the brake-drum, and having wood blocks that press on a por tion of the periphery on each side ; rods and levers perform the tightening action. There are two drums on large engines, and the equipment includes heavy weights and a steam-brake cylinder; the overwinding gear takes care of the cage, and the brakes are sufficiently powerful to hold the engines against full steam.Magnetic brakes operate by a direct pull between friction discs or shoes embracing a cylindrical drum, controlled by an electro magnet. The result is quick and positive, and finds use on certain classes of electrically-driven machinery. This type is dis tinct from the electromechanical brake previously described.

Weston brakes, also termed disc or clutch brakes, are worked either magnetically, or by end pressure obtained from a screw or hand or pedal gear. The brake contains a number of friction discs, all brought into contact simultaneously, and giving a high gripping power which increases directly as the number of discs employed. This kind is much used on cranes. A "load" brake is one fitted to the heavier cranes, the movement of the load causing a sufficient freedom between the discs when lowering is being performed, but if the driving motor is stopped the friction reasserts itself and lowering ceases, the driver thus having perfect control.

Running-in brakes afford a means of imposing a load on an engine for a period, in order to bed down the bearings and piston rings, in imitation of the actual service of the engine, but at a reduced speed. (For brakes used as dynamometers, see DYNA MOMETER.) (F. H.) Brake Shoes for Wheel-Truing.—In making brake shoes for use on mining locomotive wheels pieces of "feralun" or artificial corundum (q.v.) are set in the mould, creating a shoe that will prevent the formation of false flanges on the wheel by constantly and uniformly grinding the wheels to the proper profile. The abrasive pieces must be set carefully to secure the desired result. With shoes of this type, braking efficiency is unimpaired and no time is wasted in keeping the locomotive in the repair shop for the purpose of wheel-truing.