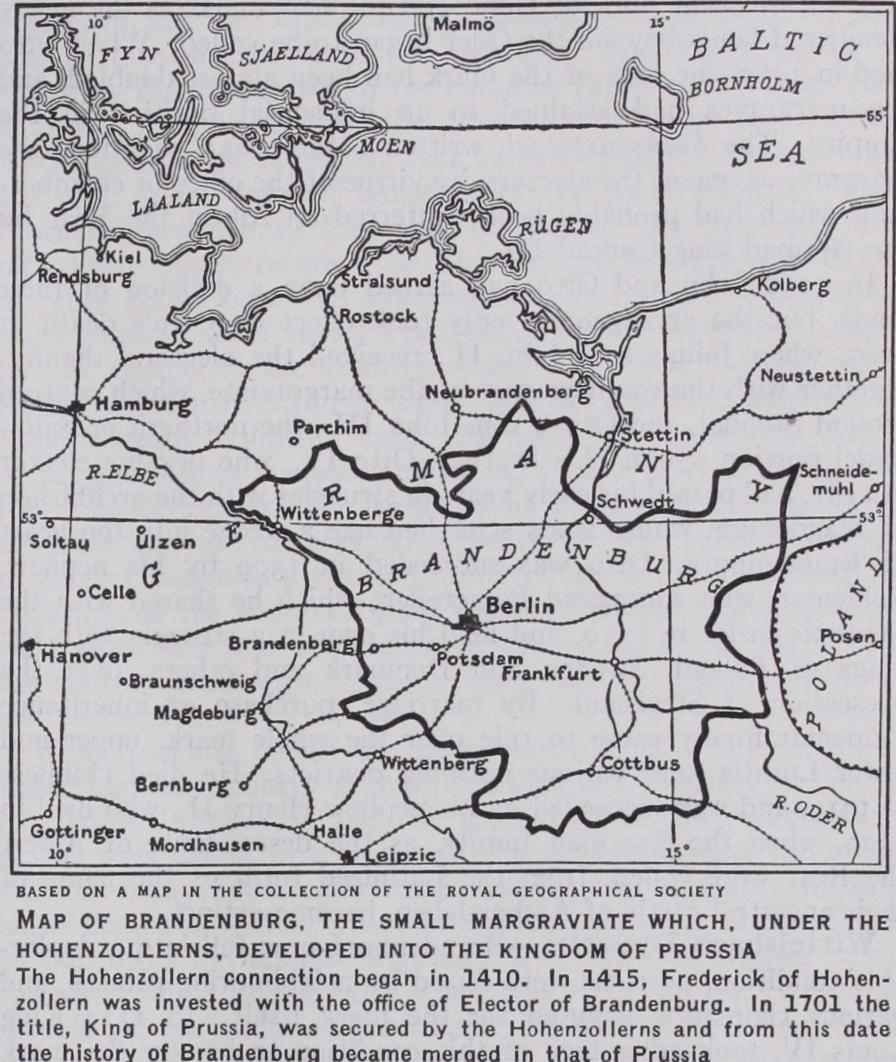

Brandenburg

BRANDENBURG, the name of a margraviate and electo rate that later became the kingdom of Prussia. The district was inhabited by the Semnones, and afterwards by various Slavonic tribes, who were partially subdued by Charlemagne, but soon regained their independence. Later Henry the Fowler defeated the Havelli, or Hevelli, and took their capital, Brennibor, from which the name Brandenburg is derived. Subsequently Gero, margrave of the Saxon east mark, pressed the campaign against the Slays with vigour, while Otto the Great founded bishoprics at Havelberg and Brandenburg. When Gero died in 965, his mark was divided into two parts, the northern portion, lying along both banks of the middle Elbe, being called the north or old mark, and forming the nucleus of the later margraviate of Brandenburg. After Otto the Great died, the Slays regained much of their terri tory, including Brandenburg. A succession of feeble masgraves ruled only the district west of the Elbe, together with a small district east of that river.

Albert the Bear.

A new era began in 1106 when Lothair, count of Supplinburg, became duke of Saxony. Aided by Albert the Bear, count of Ballenstsdt, he renewed the attack on the Slays, and in 1134 appointed Albert margrave of the north mark. About 1140, Albert made a treaty with Paibislaus, the childless duke of Brandenburg, by which he was recognized as the duke's heir, taking the title margrave of Brandenburg. Albert was the real founder of Brandenburg. Under his rule Christianity and civiliza tion were extended, bishoprics were restored and monasteries founded, and the country colonized with settlers from the lower Rhineland.When Albert died in I170, Brandenburg fell to his eldest son, Otto I. (c. 1130-84), who compelled the duke of Pomerania to own his supremacy, and slightly increased by conquest the area of the mark. Otto's son and successor, Otto II., having quarrelled with Ludolf, archbishop- of Magdeburg, was forced to own the archbishop's supremacy over his allodial lands. His successor, Albert II. (c. 1174-1220) assisted the emperor Otto IV., but later transferred his allegiance to Otto's rival, Frederick of Hohen staufen, afterwards the emperor Frederick II. His sons, John I. and Otto III., ruled Brandenburg in common until the death of John in 1266, and their reign was a period of growth and prosper ity. Districts were conquered or purchased from the surrounding dukes; the marriage of Otto with Beatrice, daughter of Wences laus, king of Bohemia, in 1253, added upper Lusatia to Branden burg; and the authority of the margraves was extended beyond the Oder. Many monasteries and towns were founded, among them Berlin, and the prosperity of Brandenburg formed a marked contrast to the disorder which prevailed elsewhere in Germany. Brandenburg appears about this time to have fallen into three divisions—the old mark lying west of the Elbe, the middle mark between the Elbe and the Oder, and the new mark, as the newly conquered lands beyond the Oder began to be called. When Otto died in 1267, the area of the mark had been almost doubled, and the margraves had attained to an influential position in the Empire. The Sachsenspiegel, written before 1235, mentions the margrave as one of the electors, by virtue of the office of chamber lain, which had probably been conferred on Albert the Bear by the German king Conrad III.

In 1258 John and Otto had agreed upon a division of their lands, but the arrangement only took effect on Otto's death in 1267, when John's son, John II., received the electoral dignity, together with the southern part of the margraviate, which centred around Stendal, and Otto's son, John III., the northern or Saltz wedel portion. John II.'s brother, Otto IV., who became elector in 1281, had passed his early years in struggles with the archbishop of Magdeburg, whose lands stretched like a wedge into the heart of Brandenburg. Otto was succeeded in 1309 by his nephew, Valdemar, who conquered Pomerellen, which he shared with the Teutonic order in 1310, and held his own in a struggle with the kings of Poland, Sweden and Denmark and others, over the possession of Stralsund. By marriage, purchase or inheritance Valdemar finally came to rule over the whole mark, upper and lower Lusatia, and various outlying districts. He died childless in 1319, and was succeeded by his nephew Henry II., who died in 1320, when the Ascanian family, as the descendants of Albert the Bear were called, from the Latinized form of the name of their ancestral castle of Aschersleben, became extinct.

Wittelsbach Dynasty.

Brandenburg now fell into a deplor able condition, portions were seized by neighbouring princes, and various claimants disputed for the mark itself. In 1323 King Louis IV. took advantage of this condition to bestow the mark upon his young son, Louis, and thus Brandenburg was added to the possessions of the Wittelsbach family, although Louis did not receive the extensive lands of the Ascanian margraves. Upper and lower Lusatia, Landsberg, and the Saxon Palatinate had been inherited by female members of the family, and passed into the hands of other princes, the old mark was retained by Agnes, the widow of Valdemar, who was married again to Otto II., duke of Brunswick, and the king was forced to acknowledge these claims, and to cede districts to Mecklenburg and Bohemia. During the early years of the reign of Louis, who was called the margrave Louis IV. or V., Brandenburg was administered by Bertold, count of Henneberg, who established the authority of the Wittelsbachs in the middle mark, which, centring round Berlin, was the most important part of the margraviate. During the struggle between the families of Wittelsbach and Luxemburg, which began in 1342, there appeared in Brandenburg an old man who claimed to be the margrave Valdemar. He was gladly received by the king of Poland and other neighbouring princes, welcomed by a large number of the people, and in 1348 invested with the margraviate by King Charles IV. This step compelled Louis to make peace with Charles, who abandoned the false Valdemar, invested Louis and his step-brothers with Brandenburg, and in return was recog nized as king. Louis recovered the old mark in 1348, drove his opponent from the land, and in 1350 made a treaty with his step brothers, Louis the younger and Otto, at Frankfurt-on-Oder, by which Brandenburg was handed over to Louis the younger and Otto. Louis made peace with his neighbours, finally defeated the false Valdemar, and was recognized by the Golden Bull of 1356 as one of the seven electors. The emperor Charles IV. took advan tage of a family quarrel over the possessions of Louis the elder, who died in 1361, to obtain a promise from Louis the younger and Otto, that the margraviate should come to his own son, Wences laus, in case the electors died childless. Louis the younger died in 1365, and when his brother Otto, who had married a daughter of Charles IV., wished to leave Brandenburg to his own family Charles began hostilities; but in 1373 an arrangement was made, and Otto, by the treaty of Furstenwalde, abandoned the margra viate for a sum of 5oo,000 gold gulden.Under the Wittelsbach rule, the estates of the various provinces of Brandenburg had obtained the right to coin money, to build fortresses, to execute justice, and to form alliances with foreign states. Charles invested Wenceslaus with the margraviate in but undertook its administration himself, and passed much of his time at a castle which he built at Tangermiinde. He diminished the burden of taxation, suppressed the violence of the nobles, improved navigation on the Elbe and Oder, and encouraged commerce by alliances with the Hanse towns, and in other ways. He caused a Landbook to be drawn up in 1375, in which are recorded all the castles, towns and villages of the land with their estates and incomes. When Charles died in 1378, and Wenceslaus became German and Bohemian king, Brandenburg passed to the new king's half-brother Sigismund, then a minor, and a period of disorder ensued. Soon of ter Sigismund came of age he pledged a part of Brandenburg to his cousin Jobst, margrave of Moravia, to whom in 1388 he pledged the remainder of the electorate in return for a large sum of money, and as the money was not repaid, Jobst obtained the investiture in 1397 from King Wenceslaus. Sigismund had also obtained the new mark on the death of his brother John in 1396, but sold this in 1402 to the Teutonic order. When, in 141o, Sigismund and Jobst were rivals for the German throne, Sigismund, anxious to obtain another vote in the electoral college, declared the bargain with Jobst void, and empowered Frederick VI. of Hohenzollern, burgrave of Nuremberg, to exer cise the Brandenburg vote at the election. (See FREDERICK I., ELECTOR OF BRANDENBURG.) In 141I Jobst died and Brandenburg reverted to Sigismund, who appointed Frederick as his representa tive to govern the margraviate. A further step was taken when, on April 3o, 1415, the king invested Frederick of Hohenzollern and his heirs with Brandenburg, together with the electoral privi lege and the office of chamberlain, in return for a payment of 400,000 gold gulden : the formal ceremony of investiture was delayed until April 18, 1417, when it took place at Constance.

Before the advent of the Hohenzollerns in Brandenburg its internal condition had become gradually worse and worse. The margraves were technically only the representatives of the em peror. But in the 13th century this restriction began to be f or gotten, and Brandenburg enjoyed an independence and carried out an independent policy in a way that was not paralleled by any other German state. This independence was enhanced by the fact that there were few large lordships with their crowd of dependants. The towns, the village communities and the knights held their lands and derived their rights directly from the margraves. The towns and villages had generally been laid out by contractors or locatores, men not necessarily of noble birth, who were installed as hereditary chief magistrates of the communities, and received numerous encouragements to reclaim waste lands. This mode of colonization was especially favourable to the peasantry, who seem in Brandenburg to have retained the disposal of their persons and property at a time when villeinage or serfdom was the ordinary status of their class elsewhere. The dues paid by these contractors in return for the concessions formed the main source of the revenue of the margraves. Gradually, however, the expenses of warfare, liberal donations to the clergy, and the maintenance of numerous and expensive households, compelled them to pledge these dues for sums of ready money. The village magistrates came to be replaced by baronial nominees, and the peasants sank into a condition of servitude and lost their right of direct appeal to the margrave. Many of the towns were forced into the same position. Others were able to maintain their independence, and to make use of the pecuniary needs of the margraves to become practically municipal republics. In the embarrassments of the margraves also originated the power of the Stdnde, or estates, the nobles, the clergy and the towns. The first recorded instance of the Stdnde co-operating with the rulers occurred in 117o; but it was not till 128o that the margrave solemnly bound him self not to raise a bode or special voluntary contribution without the consent of the estates. In 1355 the Stdnde secured the ap pointment of a permanent councillor, without whose concurrence the decrees of the margraves were invalid. Anarchy had reigned for a century before the Hohenzollern rule began : upper and lower Lusatia, the new mark of Brandenburg, and other outlying districts had been shorn away and the electorate now consisted of the old mark, the middle mark with Priegnitz, Uckermark and Sternberg, a total area of not more than 1 o,000sq.m.