Brandy

BRANDY, an alcoholic potable spirit distilled from fer mented grape juice. The term is often regarded as having the same application as the German "Branntwein" or the French "brandevin." This is not correct, as in France and Germany the respective titles are applied to any spirit obtained by distillation, the significance of the word being in the first syllable "brand" meaning burnt or burning. In France, also, brandy is known as Eau de Vie, a title which is applied equally and with legal author ity to spirit distilled from wine, cider, perry, cherries, plums and "mare." It is evident also that at one time the term "brandy" or "brandy wine" had a similarly wide significance in England. Thus the preamble to an act passed in 1690 in the reign of William and Mary runs, "Whereas good and wholesome brandies, aqua vitae, and spirits may be drawn and made from malted corn, etc.," and as late as 186o the Spirits act of that year prescribed that "all spirits which shall have had any flavour communicated thereto and all liquors whatsoever which shall be mixed or mingled with any such spirits shall be deemed a British compound called `British brandy'." This section was repealed in 188o and during the past half century the accepted sense of the term has been re stricted to spirits obtained by distillation from fermented grape juice.

The definitions in the pharmacopoeia are of interest. Thus that of the United States for 1926 describes "Spiritus Vini Vitis" as "an alcoholic liquid obtained by the distillation of the fermented juice of sound, ripe grapes and containing not less than 54% by volume of at 15.56°C. It must have been stored in wood containers for a period of not less than four years." It is "a pale amber colored liquid, having a characteristic odour and taste and an acid reaction. Specific gravity from 0.933 to 0.941 at The British Pharmaceutical Codex (1923) under the title "Spiri tus Vini Gallici" states that "brandy is obtained by distillation from the wine of grapes, and matured by age. It occurs as a pale amber coloured liquid, having a characteristic odour and taste and, as a rule, a slightly acid reaction. Specific gravity about 0.957. It contains about 4o% by volume of ethyl hydroxide. It contains minute quantities of volatile acid, aldehydes, furfural, esters and higher alcohols, to which impurities or secondary products the characteristic flavour and odour are due." Commercial brandy, however, does not correspond exactly with these definitions. As distilled it is a colourless liquid, but storage in casks, necessary to allow the spirit to mature, results in the extrac tion of certain materials from the wood imparting a pale brown colour to the liquid. This colouration varies with each cask and, for purposes of commercial standardization, a varying amount of caramel is added to bring the colour up to a uniform tint.

The brandies which enjoy the greatest popular favour are those from the Cognac district and the extension of the name to include the word Cognac, e.g., "Eau de Vie de Cognac," under the French law can be applied only to spirits so derived. Brandy is manufac tured in other districts of France such as Armagnac, Marmande, Nantes and Anjou, the spirit of poorest quality being known as Trois-Six de Montpellier.

It is of interest that, according to Beckmann, brandy is said to have been introduced into France from Italy in 1533 on the occa sion of the marriage of Henry II., then Duke of Orleans, to Cath erine de Medici. At the present time production in Italy is com paratively negligible. In other wine producing countries such as Spain and Algiers brandy is manufactured, the Spanish product being of high quality and resembling the French. In Australia and South Africa production is steadily increasing, although very little brandy is exported.

Another spirit for which the title Brandy is claimed is that obtained from the marc—the grape skins and other residue of the wine press. Although possessing characteristics of its own, Marc or "Dop" brandy, as it is called in South Africa, is generally accepted and is often of good quality.

During the period when the manufacture and sale of alcoholic liquors for beverage purposes were prohibited in the United States, there was a marked decrease in the quantity of brandy imported into this country, the figures, for example, in 1924 and 1925 being respectively 4,125 and 4,236 gallons, as compared with 510,725 in 1914.

In Great Britain and Northern Ireland also there was consider able decrease in the demand, the number of proof gallons retained for consumption from 1922 to 1927 being as follows: These figures can be compared with those for the years 1913-14 and 1921-22 both of which, however, included the whole of Ireland. Although doubtless this decrease was due partly to alteration in the popular taste, it may also be ascribed in some measure to the increase in duty, which in 1914 was 15s. id. per proof gallon in cask and in 1928 £3. 15s. 4d. full duty and £3. 12s. on spirit imported from British Dominions.

Composition.

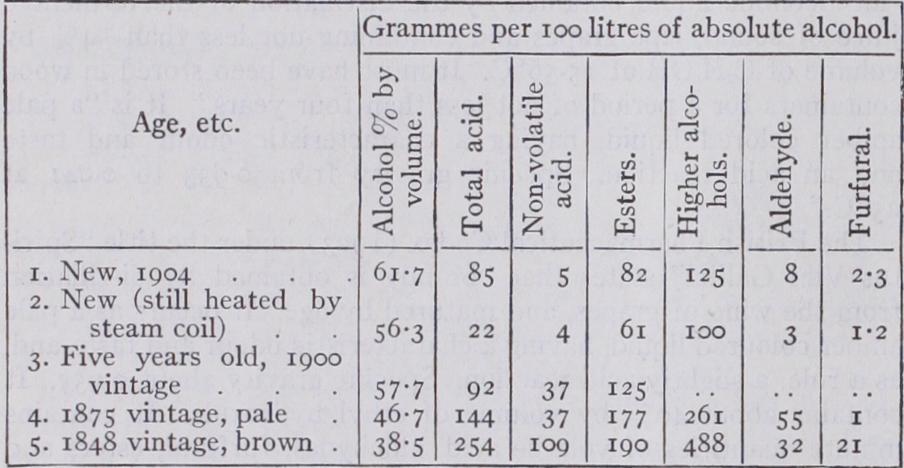

In common with other potable spirits, brandy owes its flavour and aroma to the presence of small quantities of secondary ingredients. These are dissolved in the ethyl alcohol and water which form over 99% of the spirit. The results of the analysis of five samples of genuine Cognac brandy supplied to the Royal Commission of 1909 by Dr. P. Schidrowitz were as fol lows :y- Ordonneau subjected zoo litres of 25-year-old Cognac brandy to fractional distillation and obtained the following: Grammes.

Normal propyl alcohol 40.0 Normal butyl alcohol 218.6 Amyl alcohol 83.8 Heyl alcohol . . . . . . . . o•6 Heptyl alcohol 1.5 Acetic ester . . . . . . . . . 35 •0 Propionic, butyric and caproic esters . 3•o Oenanthic ester (about) 4.0 Acetal and amines . . . . . . traces It is to one of the esters—oenanthic ester or ethyl pelargonate that the characteristic flavour of brandy is supposed more partic ularly to be due. Ordonneau attributes the peculiar fragrant odour to a small quantity of a terpene which in old brandy becomes oxi dized. The nature and proportion of the secondary ingredients vary, however, depending primarily upon the character of the wine employed, which in its turn is liable to many varying influ ences. The type of fruit and the composition of the soil are of first consideration. In the Cognac district, where the soil is mainly calcareous, the fruit is a small white grape with very acid juice, yielding a wine of inferior quality for drinking purposes. The wine produced in the Midi is also unsuitable for drinking and is dis tilled. This district was one of those ravaged by the Phylloxera, a disease which devastated the French vine-growing areas in the years 1875-78. Vineyards which had suffered were replanted with vines which were not appropriate to the soil, the resultant wine being of poor quality. In wines of this character, especially if they have been allowed to become sour, the proportion of acids, esters and other substances which are likely to be distilled with the alcohol and water is high. The method of distillation also has a marked effect upon the ultimate product. In the Cognac district a small "pot" still is generally used, and this, from its construc tion, ensures the retention in the distillate of the larger bulk of the volatile ingredients of the wine, to which the well known bouquet of Cognac brandy is due. Care is taken to carry out the distillation very slowly over a wood fire, a quantity of about 200 gallons of wine being operated upon in ten hours.

The spirit obtained from wine of inferior quality and that dis tilled from the mare contains a high proportion of secondary products. Occasionally this is used for blending with "clean" spirit obtained from grain, beet, etc., the consequent dilution of the secondary products yielding a so-called brandy, the analytical values of which correspond very closely with those of a good brandy. The stills used are of a much more complicated pattern, varying in type from the small pot still with a rectifying head to the elaborate distilling column from which fractions of higher or lower strength can be drawn as desired. A high degree of rectifi cation is possible in apparatus of this character, which is often used for the production of strong spirit for industrial purposes or for the preparation of liqueurs.

Physiological Effects.

Although brandy is still used for medicinal purposes—chiefly as a stimulant and as a hypnotic— its application in this connection is decreasing and it has been re placed to some extent by whiskey. The majority of medical wit nesses before the Spirit Commission of 1909 appeared to place little value upon the secondary products and ascribed to the ethyl alcohol any beneficial effects of the spirits in the treatment of dis ease. All alcoholic liquors have an inebriating effect due primarily to the alcohol which is common to them all (see ALCOHOL and SPIRITS). Each has effects peculiar to itself, however, and these must therefore be due to the secondary products which according to evidence given by Sir T. Lauder Brunton before the Spirits Commission of 1891 probably individually affect different parts of the cerebellum. Thus, after imbibing an excessive quantity of wine or brandy, a man has a tendency to fall upon his side, whilst it is a generally accepted fact that if the liquor has been mellowed by age its effects are not so potent. From these considerations it would appear that the peculiar effects of brandy drinking may be traced to those substances which, whilst present in the wine from which they pass to the brandy during the process of distilla tion, are themselves lost or altered in character during the ageing of the spirit. It has been proved that the higher alcohols remain practically unaltered during the maturing process. On the other hand, the furfural, aldehydes and esters undergo considerable change. They have a much more deleterious action upon the human organism and it is to them that the peculiar effects of brandy are due.

Storage and Maturation.

It is apparent, therefore, that the question of storage and maturation of brandy is of great impor tance. The spirit is stored in specially selected oak casks from which it extracts a certain quantity of colouring matter and tan nin. It is during this period that the ageing previously referred to takes place. After storage for a varying time depending upon the quality of brandy required and the demands of trade, the spirit is transferred for blending purposes to large vats, where the necessary colouring and sweetening materials are added. In the case of pale brandies the amount added is only about 0.5 to i%. The modern demand for a darker brandy with its suggestion of age encourages the blender to introduce a larger proportion than this. Brandy which is taken as a liqueur is prepared in this way from the best quality spirit and is stored for several years. The period during which storage is beneficial varies greatly, depending upon the character of the original spirit, the casks used and the place of storage. After this period has elapsed a process of deteri oration sets in and develops rapidly. The spirit loses its good flavour and is reduced in strength by evaporation of the alcohol. Thus in one instance, possibly somewhat abnormal, a cask in 1871 contained fifty-eight gallons of brandy having an apparent strength of 112.9% proof. In i894 the quantity had been reduced by evaporation to forty-nine gallons and the apparent strength to 56.5% proof. When, therefore, the maximum storage period has elapsed the spirit should be transferred to bottles, in which it can remain for many years unaltered. If for trade purposes complete bottling is not possible, a series of casks of varying ages is used. The spirit required is taken from the oldest cask and replaced by a similar quantity from the next and so on to the newest cask, which is refilled with freshly distilled spirit. The benefits of storage have been recognized officially in the United States of America, where, as previously indicated, the pharmacopoeia pre scribeF that the spirit "must have been stored in wood containers for a period of not less than four years," and in Great Britain where, under the Immature Spirits (Restriction) Act 1915, brandy cannot be delivered for home consumption unless it has been warehoused for three years.