Brass Manufactures

BRASS MANUFACTURES. The numberless applica tions of brass, and the different properties which can be obtained by varying the composition and mode of treatment of the alloy, have led in modern times to specialization. The natural conse quence has been the segregation of brass manufacture into sep arate trades or, in the case of large firms, different departments, and although their methods of treatment are similar or in some cases even identical, the distinction is still quite well-defined. In Great Britain there are several separate organizations or associa tions of manufacturers dealing with the manufacture of brass, and at least as many different trade unions.

It must be realized that the finished product of one manufac turer is the raw material of another. A piece of fine wire gauze may be taken as an example of this segregation of trades ; (1) copper and zinc are melted together and cast into an ingot ; (2) this ingot is rolled into a strip and slit into sections; (3) these sections are welded together and drawn into wire of medium gauge; (4) the fine wire drawer reduces it to the thickness of a hair; (5) this wire is woven into a gauze. This is typical of brass manufacture as a whole, and it will therefore be convenient to treat the subject under separate heads as follows: Sand Casting.—This form of the alloy is used as the first stage in the production of machined articles. Malleability is not a requisite; a certain shortness or brittleness is advantageous since it makes for ease in machining. Lead from 0.5 to 3% or more is a constituent of the alloy for this purpose and gives hard ness and stiffness, a valuable property for some products, e.g., bearings for machinery, gas and water taps, etc. A vast assort ment of articles is still produced by casting and machining, though modern practice favours extruded rods and sections wherever possible for repetition work in automatic machines. Since lead and tin are advantageous and other constituents or impurities not injurious, cast brass forms a useful means of using up the brass scrap which is the result of many manufacturing processes. This is an important point in the commercially economic use of metals and saves the expense of refining.

Sand casting of brass is for the most part a "small firm" in dustry, and it is chiefly carried on by melting in crucibles con taining 5o to soo lb. in pit fires using coke as fuel, the molten metal being poured into sand moulds. These moulds are prepared from patterns in the usual way, as in the case of cast iron. The metal consists of the coarser brands of copper and zinc, copper scrap and brass scrap of various kinds, but it is usually run down or melted into ingots as a preliminary process. No machinery other than the simplest form of hoist for lifting the crucible from the furnace is necessary, and quite a lot of work of this sort is done in Birmingham by one or two men working in a small out house in their backyard. Simple though this process appears, it is by no means an unskilled operation. Apart from the moulding, a trade in itself, the mixing of the metal, the skimming, and above all the pouring are vital operations in the production of sound castings, and the successful product will depend to a large extent upon the skill and experience of the caster.

Extrusion.

Though seized upon and exploited at first by Germany, the extrusion of brass was the invention of an English man, Alexander Dick. The alloy used for extrusion has a compo sition containing from 55 to 62% of copper with usually up to 3 to 4% of lead, and it is cast into an ingot of cylindrical shape, called a billet, as a preliminary process. The common impuri ties such as tin and iron if not excessive are not deleterious. The process itself is very simple in principle being exactly analo gous to pressing grease through a syringe. The hole in the syringe is represented by a metal plate or die having one or more holes of whatever shape may be required, the material is a billet of brass, which has been heated up to a temperature near its melting point and is placed in the cylinder behind the die, while the plunger is an exceedingly powerful hydraulic ram which forces the plastic brass through the holes in the die, thus forming long lengths of round rods or other shapes or sections as they are called. The actual temperature is a matter of importance since the metal can be too hot as well as too cold. The introduction of alloy steels which remain rigid at high temperature has been of great service to the manufacturers of extruded metal and has made possible the production of sections of almost incredible shapes such as the name of the manufacturing firm. Smoothness in the dies is very necessary, as a small defect will cause twisting or weird shapes to make their appearance.The reduction in price of many turned brass articles is largely due to the use of extruded brass rod in automatic machines. The smooth and continuous running of these machines is dependent on the material being true to size within very small limits and of similar freedom of cutting. Progress in these directions has been so great that manufacturers do not hesitate to contract to supply under stringent conditions. A slight cold drawing to size is quite usual as a finish and also gives a smoother surface. An in creasing amount of brass is extruded at about *in. diameter and is then drawn cold into wires as will be explained later under wire drawing. The metal for this purpose will be of a purer quality and contain not less than 6o% of copper.

Cold Work and Annealing.—Before describing the cold working processes a general description of the effects of cold work and the results of annealing may be helpful since these form the basis of the following processes and a knowledge of them is therefore essential. Of the different ways in which copper and zinc alloy together the most important is the alpha solid solution, which is the copper rich mixture, and it is only when this is the sole constituent, or at least the chief constituent, that cold work is commercially possible. Brass like other metals has a crystalline structure, belonging to the cubic system or highest form of sym metry. When the metal is deformed the crystal structure is broken up and under the microscope the crystals appear to have been turned into long streaks or threads, if the deformation has been carried to a considerable extent. In this state the metal has become hard and is in a condition of strain so that any attempt at further cold work would produce cracking, in fact the metal will sometimes crack spontaneously if exposed to the weather while in this state of strain. It may, however, be restored to its malleable condition by the process of annealing. This consists in heating to a temperature at which it will recrystallize. Some metals recrystallize at ordinary temperature and are said to be self-annealing, but brass does not sensibly alter until it attains a temperature of 300° Centigrade. The first result of annealing at this temperature is to render the metal actually harder, though the strains are eased and the tendency to season-crack is removed. The recrystallization is, however, excessively slow and it would take days or weeks to render the metal again malleable. As the temperature rises the speed of recrystallization increases, until at about 600° a few minutes are required for complete annealing. Under the microscope there can then be seen a closely matted mass of small but beautifully twinned crystals, which is the forma tion most to be desired by the manufacturer as well as the con sumer. Bad casting, overheating or too lengthy a period of heat ing cause irregularity and large crystals which are always a source of weakness.

Furnaces.—For the purpose of annealing a muffle furnace is used and this may be of the open or closed type. In the open type which was formerly the only type in use the chamber or oven really forms part of the flue so that the flames pass over the metal, which is also in direct contact with the flue gases. There is every opportunity for local overheating, which leads to irregular annealing, and only by the exercise of great care can this diffi culty be overcome. The only advantage of this type of furnace is the rapidity of heating obtainable with large masses of metal, but the deposition of dirt, which necessitates much cleaning, neutral izes such advantage so that in England and on the Continent the box type prevails. But in the United States where cheap supplies of distillate oils or gas are available, the open type annealing furnace is commonly used. In this type the fire and flues are separated from the interior by the walls of the furnace through which the heat is transmitted; thus there is no contact between the metal and the products of combustion, and the extra fuel needed is more than compensated for by the saving of cleaning and the preservation of the surface of the metal. Coal, coke, oil and gas are each favoured by different designers as the form of fuel. Electricity has been adopted in some cases for heating and one type of furnace has been introduced in England in which the radiators are placed round the inside of the muffle, thus com bining the efficiency and economy of the open muffle with the immunity from dirt and furnace gases given by the box muffle. With the improvement of electric supply this may well become the standard type. A further improvement is the adoption of truck loading, so that a complete loaded truck is run directly into the furnace and replaced by another when finished, the furnace being often built with doors at each end so that the truck runs right through. Another development is the continuous travelling cradle passing through a water seal at each end, the speed being adjusted so that the metal stays the correct time in the furnace. The atmosphere in the furnace is thus kept in a neutral condi tion, preventing oxidation, red stain and the necessity for clean ing except for final finish. It is usual to control the heat of these furnaces by means of pyrometers of the thermoelectric type.

Pickling and Cleaning.—The improvement in the design of muffles has led to a great decrease in the amount of pickling and cleaning required. With the open type of muffle, pickling was necessary after every annealing to remove the dirt, which would otherwise be rolled into the metal and completely spoil the sur face, but it is now frequently reserved for the final stages. The process consists in placing the brass in dilute sulphuric acid which dissolves the oxide and loosens the dirt. The metal is then "swilled" or washed in water. All traces of acid must be removed and to ensure this a weak alkali is sometimes used and the metal is then dried by means of sawdust. For metal in a suitable form such as thin strip there are automatic cleaning machines in which the metal passes by means of rollers through the pickling and swilling baths and is dried by steam heated rollers. For the final pickling bichromate of potash or soda is frequently added in small quantity to the sulphuric acid to give a good colour to the metal, and for some purposes the brass is "dipped" or placed for a short time in strong nitric acid, washed and dried. This latter process has an etching effect and destroys the absolute smoothness of the surface. It is then coiled and is ready for the warehouse.

Cold Rolling.—The first process in the production of cold rolled metal, as in all brass manufacture, is the casting of the ingot, and much care and attention needs to be directed to this, since the internal structure of the finished strip depends materially on the skill with which the ingot is cast. The underlying principles are similar to those in sand casting but there are important differ ences in detail. In the first place the metal should ideally con sist of copper and zinc only, with no impurities. As this is com mercially impossible of attainment the nearest approach to this ideal should be attempted. The increased purity of copper and zinc as a result of the electrolytic methods of production has been of great assistance to the cold roller, and the standard of metal laid down in the B.E.S.A., the A.S.T.M. and other specifications could not have been regularly attained with the old standards of purity. The World War with its demand for millions of brass cartridges had an immense effect in showing the advantage of using pure metals for the manufacture of cold working brass, and it is no longer necessary to increase the percentage of copper in a brass in the endeavour to make the alloy easily workable. The whole series of brasses from 6o% upwards of copper is available for cold rolling and most of these alloys are used by different manufacturers for various demands, but there is a dis tinct tendency to standardize certain mixtures.

The methods of casting employed fall into two classes, namely pit furnaces and crucibles or "pots" dealing with 90 to 15o lb. (in the United States, i oo to 25o lb.) of metal, and electric fur naces dealing with several hundred-weights. The pit furnaces are usually coke or anthracite fired, but gas and oil are also used with success, and in the United States anthracite is frequently employed. The electric furnace is a commercial possibility where large quantities of the same alloy have to be dealt with, especially in the United States, where it is regarded as a normal method. It is also growing in popularity in Birmingham, though the multiplicity of alloys demanded by the British market in com paratively small quantities hinders the change.

For work of this kind the crucible with its small charge has a decided advantage over the electric furnace, which to be economi cal must be kept at work continuously throughout the 24 hours and does not offer facilities for easy alteration of the composition of the metal. In weighing out the charges of metal or "heats," allowance is made for the loss of zinc during melting. This is kept down by melting the copper and brass scrap first and adding the zinc just before pouring the charge. The metal is poured into iron moulds of varying dimensions depending upon what form, e.g., sheet, strip or wire, is required in the finished article. The pouring of the metal is a skilled operation as the quality of the ingot de pends partly on the rate of pouring and also on the filling up of the hollow or "pipe" caused by the contraction on solidification. There has been some move in the direction of following steel practice and using a hot clay top or "dozzle" to the mould. This is filled with molten metal and the feeding is done automatically. Skill is again needed to prevent surface defects, which would cause rough places or splinters when rolled and are known as "spills." In some cases the ingots are planed before rolling in order to eradicate sur face defects. The moulds are dressed with various combinations of oil, tallow, resin and charcoal to prevent sticking and to give a reducing atmosphere around the molten metal, thus stopping oxidation. The temperature at which to pour the metal is highly important, but so far no satisfactory means of determining the temperature of the molten metal has been found. The skilled caster tells by the "boiling" of the metal, as felt through the stirring and a competent workman makes few mistakes. The ingots are "cropped," i.e., the "gate" end is cut off by large shears as far as there is any sign of pipe or unsoundness, and are then sent to the rolling mill. In many small works the old method of knocking off the end by taking advantage of the brittleness at black heat is still in use.

The method of brass casting known as the Durville is a depar ture from usual practice. It is based on the ability to cause molten metal to roll down a trough from one vessel to another without breaking up, especially if it is coated with a skin of adherent material. Such a skin is formed by aluminium oxide if aluminium is added to molten brass before pouring. A special apparatus is used so that the crucible is raised on one end of a "see-saw," the mould being at the other end, and the intermediate member being a trough. The metal rolls down this trough without splashing or breaking up and solidifies with the oxide skin unbroken, the latter keeping the metal from "wetting" the mould. It is claimed that ingots thus produced are free from spill, laminations and other defects, but this also is conditional on the pouring temperature, the heat of the mould, and the steady inversion—in other words, on the skill of the caster. The method is protected.

Rolling.—The rolling of metals may be described as an art, for so far it has not been possible to eliminate the skill and judg ment of the worker. The amount of reduction at different stages is standardized as far as possible in most mills, but the experience of the roller decides if it is safe to give the last reduction before annealing or whether the metal may be expected to crack. The object in view is to produce metal with a smooth surface and an internal structure of small crystal grain which will allow of the greatest amount of deformation in the later stages. The rolling process divides itself into three main stages, the breaking down, intermediate and finishing. Till comparatively recent times all rolls were made of chilled cast-iron and the majority of heavy or break ing down rolls still are. The introduction of steel rolls, particularly for finishing, has enabled the mills to produce strip and sheet with a much smoother surface than formerly, and this has proved of great service to the manufacturers of brass articles in that the fin ished articles are frequently in a condition to be polished without further smoothing. The ingots are passed several times through the breaking down rolls till the reduction amounts to 4o or 5o%. The process of rolling hardens the metal so much that at this point it becomes advisable to anneal. After annealing, the strips receive another reduction in the rolls and are again annealed. These alter nating processes are continued, the strips going to smaller rolls as they become thinner till they arrive at the highly polished fin ishing rolls and are brought to the exact thickness required, which will not vary by more than one-thousandth of an inch. Such is the skill of the rollers that limits of two or three thousandths of an inch can be obtained even on the heavy and apparently clumsy rolls. A great deal of machinery has been devised for the easy working of rolling mills. Tandem sets of rolls, reversing rolls, coiling machines, electric drive both of trains and independent rolls have improved the convenience and general appearance of the rolling mills. There is, however, one mill in Birmingham where a James Watt engine still drives the train of rolls with efficiency and economy as it has done for a hundred years.

Wire Drawing.

The usual preliminary process of making brass wire is by casting and rolling brass strip to 4 or in. thick ness. These strips are slit into approximately square sections and the ends are electrically welded so as to form a long length. This wire in embryo is drawn through dies, i.e., plates with taper holes in them of gradually decreasing diameter. The earlier stages are taken one draw at a time, the metal unrolling from one drum, pass ing through the die and being wound on another drum which is driven and so provides the power for drawing the wire through the die. The wire requires annealing at suitable stages of reduction to restore its malleability. A continuous machine is now used for the finer gauges in which the wire passes through as many as seven dies (in the United States as many as nine) in succession, each one smaller than the last ; the wire naturally lengthens as its diameter decreases and the speed increases at every point. Very ingenious methods have been devised to keep a pull on the wire at each successive draw and compensate for the varying speed. Various lubricants are used for wire drawing, the principal bases being oil and soft soap for the larger and very thin oil and soap for the smaller sizes. For the larger sizes steel dies are used, while for the fine gauges diamond dies are found to be most suitable. Wire is supplied either hard drawn, i.e., as it comes from the die, being thus suitable for springs, or more often soft annealed, i.e., having had a final annealing. This last annealing is usually car ried out in "pots" (large round pans of cast-iron or nickel chrome) with the cover "luted down" (rendered airtight) with clay to pre vent red stain and keep the bright colour of the brass. Red stain is perhaps the chief bugbear of the brass manufacturing industry and has been attributed to various causes by different metal lurgists. The adoption of closed muffles, thorough washing and general cleanliness has done much to prevent the trouble arising. This red stain spoils the appearance of rolled metal, but its presence in wire drawing is much more serious since it is very hard and rapidly cuts the dies out of shape. Consequently even the early stages of wire annealing are often carried out in pots.In the United States, instead of casting brass strips, wire is made by drawing extruded rods or by the hot or cold rolling of cast rods and the drawing of such rods into wire. The process of drawing is the same as that above described, but the wire is drawn from rods rather than from the splitting of strips into square sections.

Tube Drawing.

Brass tubes are made in two ways and are known as brazed tubes and solid drawn or seamless tubes. Brazed tubes are made from soft flat rolled strip, the curvature being imparted by drawing through a die. The edges which are then con tiguous are soldered with brazing spelter (usually equal parts of copper and zinc) by being passed through a furnace or by the aid of a blowpipe gas jet. Large tubes are bound round with wire at intervals to prevent spreading. The tubes are then drawn down to a certain extent on a mandrel in the usual way. This process is still used to a large extent particularly where no great circumfer ential strength is required, since it is much quicker and easier to roll than to draw. The soldered joint is of different composition from the material of the tube, being more brittle, and under inter nal pressure there is a strong tendency to split longitudinally. Modern practice favours the solid drawn tube as being homogene ous and therefore stronger. For this method the metal is cast in a circular mould with a core up the middle ; thus the resulting ingot is in the form of a hollow cylinder and is known as a "shell." Much care is necessary to get a good surface not only on the out side but also on the inside where the core has been. Another way in which tubes may be begun is by "cupping" in a similar manner to cartridge making, i.e., by pushing flat metal through a die with a round nosed punch. The tubes in whichever way they are started are drawn to size gradually on mandrels through dies and require constant annealing. The draw-bench is most simple, consisting of a long iron bed, somewhat resembling the bed of a lathe, with an endless chain, which is driven by power, running along its length. Grips or dogs seize the end of the tube and engage with the chain, thus drawing the tube through the die ; the tube is then reversed and the grips draw the mandrel out of the tube. The tubes require pointing or pressing together at the end to enable them to be put through the die and caught by the grips. Nearly all tubes are made of 7o% copper alloy, whether brazed or solid drawn. Any alloy with less than 7o% copper has a melting point too near that of the brazing spelter, while the extreme malleability of this alloy makes it the most suitable for seamless tubes. For admiralty condensers I % of tin is added to the alloy which considerably increases its hardness and makes it more difficult to draw. The process of draw ing makes greater demands on the malleability of the metal than rolling, and absence of impurities is essential, otherwise constant cracking and breakage will be attendant on the manufacture.In the United States, brass tubing is mostly made by drawing through a die and over a plug which is held stationary on the end of a steel rod. American brass tubes are generally made from an alloy containing 67% copper if seamless, but of 75% copper, if brazed, alloys containing even 7o% copper being usually regarded as too near the melting point of the brazing spelter.

Ornamental

Rolling and Drawing.—There are some inter esting ornamental processes of which mention should be made. Rolls with patterns cut upon them will reproduce this pattern on strip which is passed through them. In this way considerable lengths of "moulded" or embossed metal can be produced suitable for edges or borders. Fluted and oval tubes and other sections can be made by drawing through suitably shaped dies, while the well known twisted pillar is obtained by revolving the die while the drawing process is in operation.

Spinning.

This is a process for dealing with thin or moder ately thin sheets of metal. The flat piece of metal is held against a wooden chuck in the lathe and worked or spun over or into the chuck by pressing with a highly polished steel tool. The revolving metal gradually takes the form of the chuck. Flower bowls, where the inside is larger than the hole in the top, are spun over a built up chuck which takes to pieces for withdrawal. Only circular sec tions can be made, but these may bq afterwards altered in shape by other methods. This process puts great strain on the metal so that very careful annealing is required.

Presswork and Stamping.

This is the usual way in which brass is shaped to various forms, many of which are familiar as being in everyday use. The articles vary in size from a tiny eyelet made at one blow to the long shell case involving many separate processes. The difference between pressing and stamping is a mat ter of speed, the former being steady pressure, the latter a blow. The metal may be driven into a die by a punch of the same shape ( just as a notepaper press embosses the address) or it may be pressed through the die by a round nosed punch. The difference between the machines lies principally in the method of applying the power to drive the punch, the smallest consisting of a fly press with two heavy balls at the end of a rod working a screw and operated by hand. Other forms include the drop stamp, which is similar to a pile-driving plant, the press worked by a crank or eccentric with a heavy flywheel to accumulate energy for the actual moment of pressure, and hydraulic presses for very heavy work. In some cases, especially for ornamental fittings, the parts made by these machines are afterwards assembled and soldered together so as to build up a complete whole, often involving artistic design. Of such a nature are many forms of gasoliers and electroliers. Articles made out of wire, such as pins, safety pins, chains, etc., are suitable for production by entirely automatic machines, many of which are highly ingenious and appear almost human in the way they "manipulate" the material. Hot pressings have been much developed lately and now replace many small castings, since the process is well suited to mass production and turns out work to much closer limits. Most of the work so produced goes to the electrical trades.

Electroplating.

Brass forms a very good foundation for electroplating with silver, nickel or other metals and was formerly much more used for this purpose, but its position has been largely taken by the nickel silvers, since, when the plating becomes worn, the colour of the underlying metal is not so obvious. Brass can also be itself deposited electrically in an ammoniacal cyanide bath. (See ELECTROPLATE MANUFACTURES.) Finishing Processes.—Perhaps there is no metal or alloy which lends itself to such a variety of finishing processes as brass does, or which can be made to simulate so many other metals. The normal colour of brass, which can be varied by alteration of corn position, can be further changed by using lacquers of different colours, but it can also be altered by treatment with certain chemi cals such as sulphide or a salt of arsenic which gives dark to black colours. Still further alteration can be obtained by heat treatment, which gives different tints according as the temperature is varied. It is usual to cover with a clear lacquer as a final finish to prevent tarnish.It seems rather unfair that brass, which has so many valuable properties and is almost indispensable for engineering work, should always be associated in the popular mind with shoddiness. It is known as a cheap substitute for oxidized silver or bronze, it used to be a cheap substitute for gold, and it is used as a thin covering for iron to make cheap brass furniture fittings. Not on these uses, nor even on any ornamental uses does the reputation of brass depend, and were all these swept away brass would still take its stand with steel as an alloy of outstanding general adaptability and usefulness.

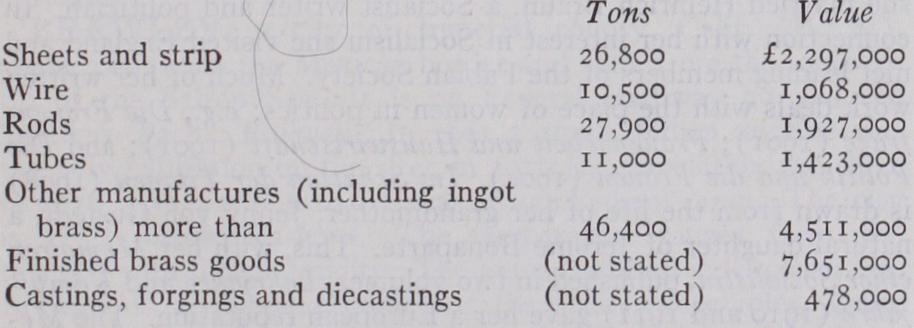

The following figures from the preliminary reports of the British Census of Production give some idea of the magnitude of the brass trade. The figures include all alloys of copper, other than nickel alloys, though the greater part is brass, and relate to the year 1924, the latest available.

It is impossible to separate the number of persons employed in the manufacture of brass, since the only available figures include copper, aluminium and other metals. A large amount of brass is also produced by railway companies, shipbuilding firms and other large engineering works for their own use or for use in their manu factures and this is not included in the above returns. The export and import figures are similarly grouped with other metallic products.

The methods of manufacture which have been described as in use in England apply equally to France, Germany, the United States and other countries, and may be taken as typical of brass manufacture in general. The brass articles of the East are mostly made from sheet, strip or wire imported from the above countries.

See J. G. Horner, Brass Founding (1918) ; Brit. Engineering Stand ards Assoc., British Stand. Specification for Brass Bars (1926) ; W. G. Lathrop, The Brass Industry in the United States (1926). (S. P.)